Abstract

The current study examined selective attention toward emotional images as a risk factor for major depressive disorder (MDD). Using multiple indices of attention in a dot-probe task (i.e., reaction time [RT] and eye-tracking-based measures) in a retrospective, high-risk design, we found that women with remitted MDD, compared to controls, exhibited greater selective attention toward angry faces across RT and eye-tracking indices and greater attention toward sad faces for RT measures. Second, we followed women with remitted MDD prospectively to determine if the attentional biases retrospectively associated with MDD history would predict MDD recurrence across a two-year follow-up. We found that women who spent a greater proportion of time looking at angry faces during the dot-probe task at the baseline assessment had a significantly shorter time to MDD onset. Taken together, these findings provide converging retrospective and prospective evidence that selective attention toward angry faces may increase risk for MDD recurrence.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a recurrent condition associated with significant impairment in quality of life, productivity, and interpersonal functioning (APA, 2000). MDD is the primary cause of disability worldwide (World Health Organization, 2012), and approximately 16% of Americans will experience at least one episode of MDD in their lifetime with women having double the risk of men (Kessler et al., 2003). Over 60% of individuals who develop an initial episode of MDD will experience at least one recurrent episode, and the risk of recurrence increases with each additional episode (Kessing, Hansen, Andersen, & Angst, 2004).

Thus far, one of the most promising models for understanding mechanisms underlying the development, maintenance, and recurrence of MDD has come from cognitive theories of depression (e.g., Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Clark & Beck, 1999). According to these models, biases in attention toward, interpretation of, and memory for negative information contribute to the development and maintenance of MDD, and, during remission from MDD, these cognitive biases remain, serving as stable, trait-like risk factors that increase risk for MDD recurrence (Beck, 2008). Preliminary evidence suggests that selective attention toward depression-relevant stimuli (e.g., sad faces) may be one such risk factor for MDD recurrence, as individuals with current or remitted MDD are more likely to selectively attend toward sad faces whereas those with no history of MDD are more likely to attend toward happy faces (Fritzsche et al., 2010; Joormann & Gotlib, 2007).

To examine attentional biases, these studies used the dot-probe task (cf. MacLeod, Mathews, & Tata, 1986), in which two faces are presented on the screen at the same time, one emotional and one neutral. Following this, the faces disappear and a probe appears in the location of one of the faces. Selective attention toward emotional faces (e.g., sad or happy vs. neutral) is inferred when participants’ reaction times (RT) are faster when the probe appears in the location of the emotional face than in the location of the neutral face. The assumption underlying this approach is that RTs to the probe will be faster if one’s attention is already allocated to that side of the computer screen. However, recent research has questioned the reliability and validity of RT-based measures of attention using the dot-probe task (e.g., Kappenman, MacNamara, & Proudfit, in press; Price et al., in press, Schmukle, 2005; Staugaard, 2009; Stevens, Rist, & Gerlach, 2011), suggesting that more direct measures of attentional allocation are needed (e.g., eye tracking).

Although no studies of which we are aware have examined eye-tracking indices of attentional bias with the dot-probe task among individuals with remitted MDD, eye-tracking studies of attentional allocation using attention-based tasks may help clarify processes underlying attentional biases in remitted MDD. For example, Sears and colleagues (2011) used a passive viewing task to examine patterns of sustained attention toward emotional images in remitted depressed and control participants. They found that, consistent with previous research (e.g., Fritzsche et al., 2010; Joormann & Gotlib, 2007), individuals with remitted MDD, relative to never depressed controls, spent less time viewing positive images. However, in contrast to prior findings, there were no significant group differences in gaze duration toward dysphoric images. Notably, this study also provided novel evidence that individuals with remitted MDD display attentional bias toward other forms of negative information. Specifically, compared to controls, individuals with remitted MDD spent greater time looking at threatening images. These findings may have important implications for future research given that prior studies of attentional biases in remitted MDD have not evaluated attention toward threatening emotions in faces (e.g., Fritzsche et al., 2010; Joormann & Gotlib, 2007). Therefore, future research examining attentional bias in remitted depression using the dot-probe task should include both sad and angry faces to provide a more robust test of selective attention toward depression-relevant stimuli.

A second limitation of prior research is that the link between remitted MDD and attentional biases has only been examined cross-sectionally. It is unclear, therefore, whether these attentional biases actually increase risk for MDD recurrence as predicted by theory. This said, however, there are data from previous studies showing that attentional bias toward depressogenic stimuli predicts prospective increases in depressive symptoms (e.g., Beevers & Carver, 2003; Beevers, Lee, Wells, Ellis, & Telch, 2011). What remains unclear is whether these biases predict onset or recurrence of MDD. Additional prospective research is essential to determine specific underlying risk factors for MDD recurrence so that these can be targeted in interventions. For example, this knowledge could contribute to further development of clinical intervention programs that seek to retrain cognitive biases through techniques such as computer-based attention-bias modification. This approach has been effective for the treatment of anxiety (for reviews, see Hakamata et al., 2010; Hallion & Ruscio, 2011), and there is preliminary support that this treatment reduces depressive symptoms in dysphoric undergraduates (Wells & Beevers, 2010; Yang, Ding, Dai, Peng, & Zhang, in press) and individuals with remitted MDD (Browning, Holmes, Charles, Cowen, & Harmer, 2012). Programs such as these may be a key component of efforts to reduce MDD recurrence among at-risk populations.

Given the limitations of prior research, the aims of the current study were twofold. First, the current study aimed to examine the link between attentional biases and remitted MDD in women using multiple indices of attention allocation in a dot-probe task (i.e., RT and eye-tracking-based measures). We employed a retrospective, high-risk design similar to those used in previous studies of cognitive vulnerability in depression (e.g., Alloy, Lipman, & Abramson, 1992; Alloy et al., 2000; Stone, Uhrlass, & Gibb, 2010). The rationale for this design is that vulnerability factors should exist independent of depression state and, therefore, represent risk factors for the development and recurrence of MDD. Thus, if current measures of attentional bias correlate with past history of MDD, then they may reflect potential mechanisms of future risk for MDD. Based on previous research, we predicted that women with remitted MDD, relative to never-depressed controls, would exhibit selective attention toward sad and angry faces.

Our second goal was to determine if the attentional biases associated with past MDD history would predict prospective onsets of new MDD episodes across a two-year follow-up among women with remitted MDD. This longitudinal approach provides a stricter test of attentional bias as a risk factor for MDD recurrence because cross-sectional and retrospective designs cannot determine whether attentional biases are merely correlates or consequences of depression. The current study is the first of which we are aware to prospectively examine if attentional biases increase risk for MDD recurrence. This is an essential next step in identifying causal risk factors for MDD. Of note, we focused exclusively on women in this study as they have twice the risk for MDD as men (Kessler et al., 1993). Given that women carry the greatest clinical burden of depression, they are in greatest need for efforts to identify mechanisms of risk for MDD recurrence.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were 160 women recruited from the community as part of a larger study of the intergenerational transmission of depression. Women in the remitted depressed group (rMDD; n = 57) were required to have a lifetime history of MDD but to currently be in full remission from the disorder. Among women in the rMDD group, 51% (n = 29) had a past history of recurrent MDD (i.e., two or more past MDD episodes). Among the rMDD group, 19% (n = 11) had a history of a past anxiety disorder (panic disorder [n =2], posttraumatic stress disorder [n =8], and social phobia [n =2]), 18% (n = 10) had a past alcohol [n = 9] and/or substance [n = 5] abuse disorder, and 5% (n = 3) had a past eating disorder (binge eating disorder [n =2] and bulimia nervosa [n =1]). Women in the control group (CTL; n = 103) were required to have no lifetime diagnosis of any DSM-IV mood disorder. Among the CTL group, 6% (n = 6) had a history of a past anxiety disorder (agoraphobia [n =1], obsessive compulsive disorder [n =1], panic disorder [n =1], posttraumatic stress disorder [n =1], and social phobia [n =1]), 9% (n = 9) had a past alcohol [n = 8] and/or substance [n = 4] abuse disorder, and 2% (n = 2) had a past eating disorder (anorexia nervosa [n =1] and bulimia nervosa [n =1]). Exclusion criteria for both groups included any current Axis I diagnosis, organic mental disorder, alcohol or substance dependence within the last six months, or history of psychotic symptoms, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. The average age of women in our sample was 40.27 (SD = 6.64, Range = 24–53), 78% were currently married, and 90% were Caucasian. The median annual family income was $55,001 to $60,000 and 46% of women had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Notably, there were no significant group differences in age, marital status, race, or education among rMDD and CTL women (all ps > .34). However, rMDD women had marginally lower family income than CTL women, t(158) = −1.83, p = .07.

Measures

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002) was used to assess for histories of DSM-IV Axis I disorders. The SCID-I is a widely used diagnostic interview with well-established psychometric properties (Lotta, Leurgens, & Arntz, 2011; Zanarini & Frankenburg, 2001). At the baseline assessment, the SCID-I interview was used to assess for lifetime histories of Axis I disorders and at the follow-up assessments, it was used to assess for new onsets of MDD. To meet criteria for full remission from MDD and qualify for the rMDD group during the baseline assessment, the MDD criterion A symptoms within the SCID-I interview must have been scored as absent in the past two months (i.e., participants who scored a 2 or 3 on criterion A symptoms in the past two months did not qualify as fully remitted and were excluded). In addition, participants could not meet threshold criteria for any other symptoms of depression in the past 2 months (i.e., participants who scored a 3 were excluded). To assess inter-rater reliability, a subset of 21 SCID interviews was coded by a second interviewer. Inter-rater reliability for diagnoses of MDD was excellent (κ = 1.0).

Women’s symptoms of depression were assessed at the baseline assessment using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). The BDI-II is a 21-item questionnaire that assesses the severity of current depressive symptoms in the past two weeks, which has demonstrated good internal consistency and validity in previous research (Dozois, Dobson, & Ahnberg, 1998). BDI-II scores were significantly higher among rMDD women (M = 10.27, SD = 8.83) than CTL women (M = 4.22, SD = 5.31), t(158) = 5.53, p < .001.

Women’s attentional biases for facial displays of emotion were assessed at the baseline assessment using a modified dot-probe task (cf. MacLeod et al., 1986). Stimuli for the dot-probe task consisted of pairs of facial expressions that contained one emotional (angry, happy, or sad) and one neutral photograph from the same actor taken from a standardized stimulus set (Tottenham et al., 2009). Photographs from each actor (16 males and 16 females) were used to create angry-neutral, happy-neutral, and sad-neutral stimulus pairs (96 pairs total). Women sat a distance of 65cm away from the computer monitor and each of the two facial stimuli was 12.5 cm tall × 12.5 cm wide. Each stimulus pair was presented in random order in each of the 2 blocks, with a rest in between blocks (192 trials total). Each trial began with the presentation of a central fixation cross, and participants were required to make a central fixation before stimuli were presented. Stimuli were presented for 1000 ms, followed by a probe (one or two asterisks) replacing one of the pictures. Following presentation of the dot probe on the screen, participants were asked to indicate whether the probe consisted of one or two asterisks as quickly as possible using a response box. The probe was presented with equal frequency in the location of the emotional and neutral faces. The inter-trial interval varied randomly between 750 and 1250 ms. Trials with response errors were excluded (.94%) as were trials with response times less than 150 ms or greater than 1500 ms (1.09%). In addition, trials without at least one fixation on a facial stimulus were excluded (16.54%). One hundred and eighty-nine participants completed the dot-probe task; however, participants who lost more than 50% of their trials (>96 trials) were excluded (n = 29). Therefore, 160 participants were included in the current study.1

Two indices of attentional bias were used for this study. First, focusing on manual reaction times (RT), we calculated bias scores separately for each emotion type (angry, happy, sad) by subtracting the mean RT for cases in which the probe replaced the emotional face from mean RT for cases in which the probe replaced the neutral face (cf. Mogg, Bradley, & Williams, 1995). Positive bias scores reflect selective attention toward the emotional faces, whereas negative scores indicate attentional avoidance of the emotional faces. In addition, to provide a more direct index of attentional allocation, gaze location and duration was measured using a Tobii T60XL eye-tracking monitor (60Hz data rate; 1920 × 1200 pixels), which uses infrared Pupil Centre Corneal Reflection to illuminate the eye and calculate gaze direction in relation to the monitor location. Before the dot-probe task, participants completed a five-point calibration of the eye tracker where they were asked to look at specific points at the center and corners of the monitor. Accuracy of the calibration was confirmed by visual inspection of fixations recorded during the calibration procedure. Fixations were defined as gaze allocation in a predefined area of interest lasting at least 100ms. The key eye-tracking variables of interest were the proportion of time within each trial the participant fixated on the emotional versus the neutral expressions. Proportion gaze scores were calculated separately for each emotion type (angry, happy, sad) by dividing the time within each trial the participant fixated on the emotional face by the total time spent fixated on either face during the trial. Proportion scores above .50 reflect selective attention toward the emotional faces, whereas scores below .50 indicate attentional avoidance of the emotional faces. RT and eye-tracking indices were significantly, though modestly, correlated for angry, r = .26, p = .001, and sad, r = .19, p = .02, faces but not happy faces, r = .01, p = .93.

Procedure

Potential participants were recruited from the community through a variety of means (e.g., television, newspaper, and bus ads, flyers). Participants responding to the recruitment advertisements were initially screened over the phone to determine potential eligibility. Upon arrival at the laboratory, participants were asked to provide informed consent. Next, a research assistant administered the SCID-I and then participants completed the dot-probe task. Following this baseline assessment, participants completed follow-up appointments, which occurred 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after the initial assessment. At each of these assessments, a research assistant assessed for any MDD episodes that may have occurred in the previous six months using the SCID-I. All study procedures were approved by the University’s Internal Review Board.

Results

Retrospective analyses

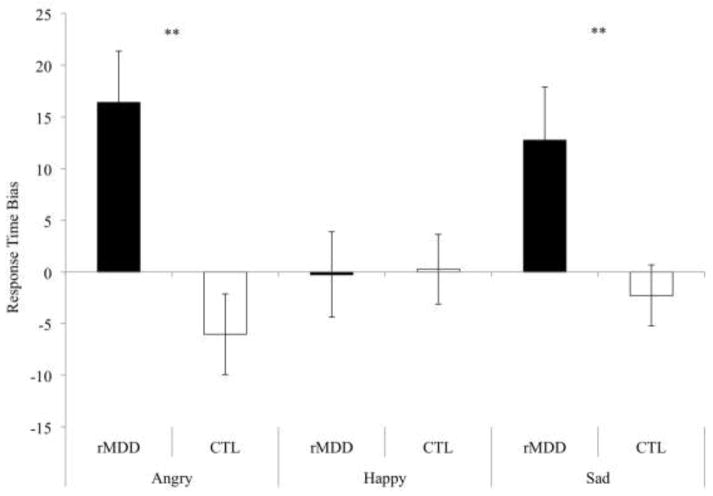

First, we examined the relation between women’s MDD history and their RT biases to emotional faces. Specifically, we used a 2 (group: rMDD, CTL) × 3 (emotion: angry, happy, sad) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with RT bias scores serving as the dependent variable. The main effect of group was significant, F(1, 158) = 16.40, p < .001, ηp2 = .09; however, the main effect of emotion was nonsignificant, F(2, 316) = .98, p = .38, ηp2 = .01. Importantly, the group × emotion interaction was significant, F(2, 316) = 3.71, p = .03, ηp2 = .02. The form of this interaction is depicted in Figure 1. Tests of simple main effects within each emotion type revealed that the rMDD group, compared to the CTL group, exhibited greater RT bias scores toward angry, t(158) = −3.49, p = .001, reffect size = .28, and sad, t(158) = −2.73, p = .01, reffect size = .21, faces. In contrast, the group difference for happy faces was not significant, t(158) = .10, p = .92, reffect size = −.01. We then conducted one-sample t tests to determine whether either groups’ RT bias scores differed significantly from zero, thereby indicating the presence of a true bias. These tests were significant among the rMDD group for both angry, t(56)= 3.30, p = .002, and sad, t(56)= 2.48, p = .02, faces. In contrast, the RT bias scores did not differ significantly from zero in the CTL group for angry, t(102) = −1.55, p = .13, or sad, t(102) = −0.78, p = .44, faces. To examine the robustness of the group differences we conducted a series of follow-up tests. We found that the significant group differences in RT bias to angry, F(157) = 13.61, p < .001, reffect size = .28, and sad, F(157) = 6.12, p = .02, reffect size = .19, faces were maintained when we statistically controlled for the influence of women’s current depressive symptom levels (BDI-II), suggesting that the results are at least partially independent of women’s concurrent depressive symptoms. In addition, the significant group differences were maintained for angry, F(157) = 12.14, p = .001, reffect size = .27, and sad, F(157) = 8.09, p = .01, reffect size = .22, faces when controlling for family income showing that the results are at least partially independent of this known risk factor for MDD as well.

Figure 1.

Women’s response time bias scores across the three facial expression types as a function of women’s major depressive disorder (MDD) history. Note: Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

** p < .01

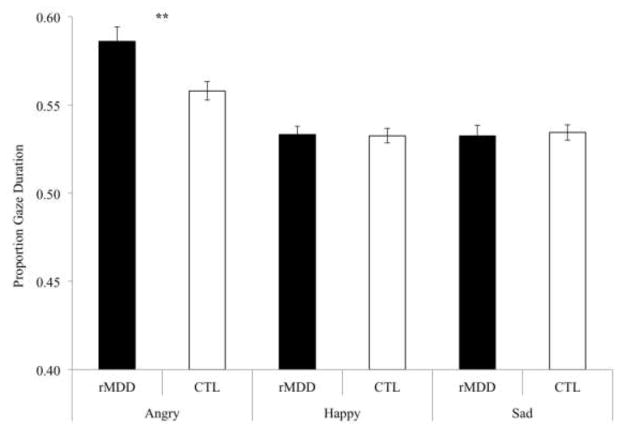

Next, we examined the relation between women’s MDD history and their proportion of gaze duration toward emotional faces. Similar to the analyses reported above, we used a 2 (group) × 3 (emotion) repeated measures ANOVA with proportion gaze duration serving as the dependent variable. The main effect of group was nonsignificant, F(1, 158) = 2.70, p = .10, ηp2 = .02, but there was a significant main effect of emotion, F(2, 316) = 41.83, p < .001, ηp2 = .21, as well as a significant group × emotion interaction, F(2, 316) = 5.76, p = .004, ηp2 = .04. The form of this interaction is depicted in Figure 2. Tests of simple main effects within each facial expression type revealed that the rMDD group exhibited greater proportion of gaze duration toward angry faces than did the CTL group, t(158) = 3.02, p = .003, reffect size = .23. In contrast, there were no significant group differences in gaze duration toward happy, t(158) = −.09, p = .93, reffect size = .07, or sad, t(158) = .25, p = .80, reffect size = −.02, faces. Importantly, the significant group difference in gaze proportion to angry faces was maintained when we statistically controlled for the influence of women’s current depressive symptoms, F(157) = 6.67, p = .01, reffect size = .20, and family income, F(157) = 7.92, p = .01, reffect size = .22.

Figure 2.

Women’s proportion gaze duration scores across the three facial expression types as a function of women’s major depressive disorder (MDD) history. Note: Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

** p < .01

Prospective analyses

Of the 160 women participating in the initial assessment, 138, 130, 115, and 124 participated in the 6, 12, 18, and 24-month follow-ups, respectively. If a woman missed a follow-up assessment, the following assessment focused on the entire time since the previous completed assessment. For example, if a woman missed the 6-month assessment, the 12-month assessment focused on any MDD episodes since Time 1. Therefore, follow-up data were available for 146 women. During the 2-year follow-up, 15 of the 53 women in the rMDD group with follow-up data met criteria for a new episode of MDD (28.30%) and 4 of the 93 the women in the CTL group with follow-up data met criteria for a first episode of MDD (4.30%). Given the low base rate of MDD onset within CTL participants, we could not examine predictors of MDD onset in this group. Therefore, the final sample for our prospective analyses consisted of 53 rMDD women.2

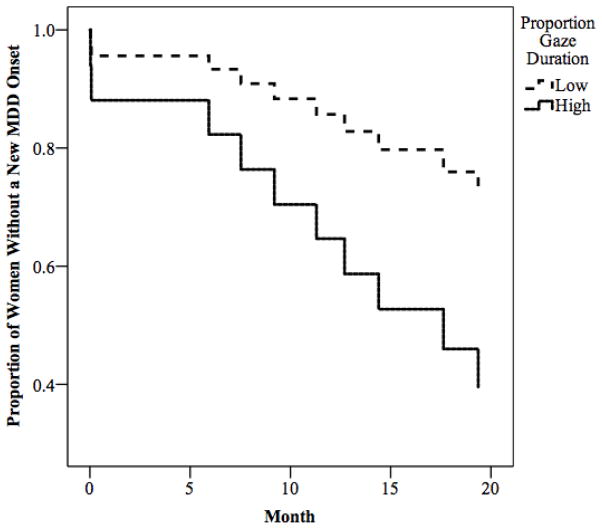

Using survival analysis, we then tested the hypothesis that the measures of attentional bias that were significant in the retrospective analyses would also predict prospective onsets of MDD episodes. Specifically, we examined if women’s RT bias scores for angry or sad faces or women’s proportion of gaze duration toward angry faces would predict MDD recurrence among women in the rMDD group. Women’s RT bias toward angry, Wald = .17, p = .68, and sad, Wald < .001, p = .98, faces did not predict MDD onset in rMDD women. In contrast, women’s proportion of gaze duration toward angry faces predicted significantly shorter time to MDD onset, Wald = 4.99, p = .03. To visually depict these findings, we repeated the analysis using upper and lower quartiles of women’s proportion gaze duration scores (see Figure 3). As seen in the figure, higher proportion of gaze duration toward angry faces predicted shorter time to MDD onset. Evaluating the robustness of these effects, we found that that the relation between women’s proportion of gaze duration toward angry faces and time to MDD onset was maintained even after statistically controlling for the influence of women’s depressive symptoms at the baseline assessment, Wald = 4.25, p = .04, past history of recurrent MDD (yes or no), Wald = 4.63, p = .03, and family income, Wald = 4.68, p = .03, suggesting that the predictive validity of selective attention toward angry faces is at least partially independent of these known risk factors of MDD recurrence.

Figure 3.

Results of survival analysis predicting time to depression onset among women with remitted MDD as a function of proportion gaze duration toward angry faces.

Finally, given potential concerns that these findings were confounded by women’s past history of anxiety disorders, we should note that all retrospective and prospective results were maintained even after including lifetime history of anxiety disorders (yes or no) as a covariate in our analyses (all ps < .05).3

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to investigate attentional biases in women currently remitted from MDD and to determine whether these attentional biases prospectively predicted MDD recurrence across a two-year follow-up period. Using a dot-probe task with multiple indices of attention allocation (i.e., RT and eye-tracking-based measures), we predicted that women with remitted MDD, relative to controls, would exhibit selective attention toward sad and angry faces and that these attentional biases would prospectively predict the recurrence of MDD episodes among women with a past history of MDD. Consistent with prior research examining RT in the dot-probe task (Fritzsche et al., 2010; Joormann & Gotlib, 2007), we replicated the finding that women with remitted MDD display greater RT bias scores for sad faces than control women. In addition, we extended this finding by showing that this RT bias is also present for angry faces. Using eye-tracking measures, we found that women with remitted MDD exhibited greater proportion of gaze duration toward angry but not sad faces, which is consistent with a prior study that examined sustained attention toward emotional stimuli in remitted MDD (Sears et al., 2011). However, in contrast to prior research, (Fritzsche et al., 2010; Joormann & Gotlib, 2007; Sears et al., 2011), we found no significant group differences in RT bias or proportion gaze duration toward happy faces. Finally, we examined if the measures of attentional bias that were retrospectively associated with remitted MDD would also prospectively predict MDD recurrence. We found that women’s RT bias scores for angry and sad faces did not predict MDD recurrence among remitted women; however, proportion of gaze duration toward angry faces did. Specifically, women who spent a greater proportion of time looking at angry facial stimuli during the dot probe at the baseline assessment had a significantly shorter time to depression onset. Importantly, our results were at least partially independent of other known risk factors for MDD including baseline depressive symptoms, family income, and past histories of recurrent MDD and anxiety disorders. Taken together, these findings provide convergent retrospective and prospective evidence that selective attention toward angry faces (as measured by a direct eye-tracking based measure of attentional allocation) is an important cognitive vulnerability underlying risk for MDD recurrence in women.

As this study is the first of which we are aware to examine attentional biases as a predictor of MDD recurrence, these findings have potentially important implications for clinical assessment and treatment of individuals at risk for recurrent MDD. For example, the identification of cognitive vulnerabilities associated with MDD recurrence may aid clinicians in identifying remitted individuals at highest risk for recurrence, even in the absence of other clinical signs and symptoms. Importantly, this study adds to growing evidence that selective attention toward angry faces measured via eye-tracking may be one such cognitive vulnerability (see also Sears et al., 2011). Because eye-tracking is a relatively inexpensive method of analyzing attentional biases, a test of selective attention toward emotional faces could easily be implemented in clinical settings as a method to identify individuals who are at highest risk for MDD recurrence. Furthermore, early identification of at-risk populations could lead to more effective prevention efforts to reduce MDD recurrence. One potential preventative program could focus on further development of computer-based attention-bias modification programs that seek to reduce depressive symptoms by retraining attention away from negative stimuli (e.g., Browning et al., 2012; Wells & Beevers, 2010; Yang et al., in press). For example, Browning and colleagues (2012) found that modifying (i.e., reducing) selective attention toward faces portraying anger or disgust among individuals with remitted MDD led to prospective reductions in two measures of recurrence risk: depressive symptoms and the cortisol awakening response. Taken together, these findings and those of the current study suggest that naturally-occurring selective attention toward angry faces increases risk for MDD recurrence and that attention-bias modification programs designed to reduce this bias may be an effective preventative measure to reduce MDD recurrence.

Our findings raise important questions regarding the specificity of attentional biases to emotional images in remitted depression. Seminal studies examining attentional biases in MDD using the dot-probe task found that currently depressed individuals exhibited selective attention toward sad faces but not angry or happy faces (e.g., Gotlib, Krasnoperova, Yue, & Joormann, 2004). However, prior to the current study, a robust test of specificity had not been conducted among individuals with remitted MDD as previous studies of remitted depression only included sad and happy faces in the dot-probe task (Fritzsche et al., 2010; Joormann & Gotlib, 2007). Notably, the results of current study suggest that selective attention toward angry faces may be more strongly associated with risk for MDD recurrence than attention toward sad or happy faces, which is consistent with the results of a recent eye-tracking study of individuals with remitted MDD using a passive viewing task (Sears et al., 2011). One possible explanation for this discrepancy between attentional bias in remitted versus current MDD is that the salience of self-referential versus externally-referential cues change across the progression of the disorder. For example, for currently depressed individuals, attention is more likely to be oriented toward self-referential negative information (e.g., sad faces) as it is more congruent with one’s depressed mood (cf. Mogg & Bradley, 2005). However, in the absence of current depression, remitted individuals may shift their attention toward externally-relevant cues that signal interpersonal rejection (e.g., angry faces). This is consistent with interpersonal theories of depression that suggest individuals with a history of MDD are more likely to engage in behaviors that elicit rejection from others (e.g., Coyne, 1976; Joiner & Metalsky, 1995) as well as research suggesting that biased processing of rejection cues may contribute to an increase in rejection-eliciting behaviors among at-risk individuals (Gotlib & Hammen, 1992). Importantly, these cues may be even more salient for women, as women are more likely to generate interpersonal stress and experience depression in response to interpersonal stressors than men, leading some to characterize depression in women as “relational psychopathology” (e.g., Hammen, 2003). For women with a history of MDD, it may be that attention toward interpersonal cues that suggest rejection, anger, or criticism emerges as a trait-like risk factor for MDD recurrence, which is consistent with the results of the current study. Given that the current study only examined attentional biases in women with remitted MDD, our findings for selective attention toward angry faces may have been particularly strong. Future research will be necessary to determine if selective attention toward angry faces also serves as a risk factor for MDD recurrence in men.

In our study, there were several notable discrepancies among our findings for RT vs. eye-tracking indices of attention, which were unexpected. In our retrospective analyses, we found a consistent pattern of group differences for selective attention toward angry faces across our RT and gaze duration measures of attention. However, when examining attentional biases for sad faces, we found group differences in selective attention toward sad faces for RT bias scores but not for gaze duration proportion scores. Relatedly, we also found discrepancies when comparing RT bias scores and eye-tracking indices in our prospective analyses. Specifically, we found that women’s RT bias scores for angry and sad faces did not predict MDD recurrence among remitted women but that women’s proportion of gaze duration toward angry faces did. These discrepancies may be most parsimoniously explained by recent research demonstrating that eye-tracking indices of attention are not strongly related to RT measures in the dot-probe task (e.g., Stevens et al., 2011; Waechter, Nelson, Wright, Hyatt, & Oakman, 2014). Furthermore, recent research has demonstrated that eye-tracking indices display greater retest reliability than RT-based measures in the dot-probe task (see Price et al., in press). Therefore, these studies and ours suggest that eye-tracking indices in the dot-probe task may emerge as the best predictors of risk for MDD recurrence as they are more reliable across multiple time points.

The current study demonstrated several strengths including the prospective design and the multi-method approach to the assessment of attentional biases. However, there were some limitations that highlight areas for future research. First, although this study was an essential next step to determine mechanisms of risk for depression recurrence among women, future research should focus on both men and women to determine whether similar patterns of findings would be observed in men. Second, the current study only examined attentional biases at the baseline assessment. Therefore, we were unable to determine the reliability of our RT bias and eye-tracking measures over time. This said, prior research has established good retest reliability for eye-tracking indices in the dot-probe task (Price et al., in press). Third, the study only examined attentional biases within a dot-probe task. Future research would benefit from the inclusion of a task designed to examine attentional biases to emotional stimuli in a more unconstrained manner, such as a passive viewing paradigm. Fourth, the current study was only able to examine attentional bias as a predictor of recurrence among remitted women and was unable to test if these biases would also predict first MDD onset among never-depressed individuals. Therefore, future research will be necessary to prospectively examine the role of attentional bias in the risk for the development of first MDD onset. Finally, although our study focused on the link between depression and attentional biases, there is always the possibility that the results were driven by some unmeasured third variable. For example, borderline personality disorder has been associated with attentional biases toward threatening facial expressions (e.g., Daros, Zakzanis, & Ruocco, 2013; Veague & Hooley, 2014), suggesting that unmeasured borderline personality traits could have contributed to the current findings. Unfortunately, the current study did not include any assessments of personality pathology and future research is needed to determine how the presence of (comorbid) symptoms of borderline personality disorder may influence attentional bias to emotional images in MDD.

In conclusion, the current study provides converging retrospective and prospective evidence for the role of selective attention toward angry faces in remitted MDD and suggests that it may increase risk for MDD recurrence among women with a history of MDD. In addition, these results complement and extend the findings of prior studies that have documented the presence of attentional biases to emotional images in remitted MDD (e.g., Fritzsche et al., 2010; Joormann & Gotlib, 2007; Sears et al., 2011). Importantly, this study is the first to examine whether RT and eye-tracking indices of attentional biases to emotional images prospectively predict the development of new MDD episodes among women with a history of prior MDD. Our results underscore the importance of determining how individuals at risk for MDD recurrence process emotional information and have important implications for the growing interest in using attention-bias modification paradigms to treat depressed and at-risk individuals.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant HD057066 and National Institute of Mental Health grant MH098060 awarded to B. E. Gibb. We would like to thank Ashley Johnson, Lindsey Stone, Andrea Hanley, Anastacia Kudinova, Sydney Meadows, Michael Van Wie, Devra Alper, Cope Feurer, Eric Funk, and Effua Sosoo for their help in conducting assessments for this project.

Footnotes

Excluded participants did not differ significantly from included participants on any study variables.

We should note that we re-ran our survival analyses across the full sample of 146 women with follow-up data and all of the findings were maintained.

Details of these analyses are available from the first author.

References

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Hogan ME, Whitehouse WG, Rose DT, Roinson MS, et al. The Temple-Wisconsin vulnerability to depression project: Lifetime history of axis I psychopathology in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:403–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Lipman AJ, Abramson LY. Attributional style as a vulnerability factor for depression: Validation by past history of mood disorders. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 1992;16:391–407. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, editor. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR®. American Psychiatric Pub; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. The evolution of the cognitive model of depression and its neurobiological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:969–977. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Carver CS. Attentional bias and mood persistence as prospective predictors of dysphoria. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:619–637. [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Lee H, Wells TT, Ellis AJ, Telch MJ. Association of predeployment gaze bias for emotion stimuli with later symptoms of PTSD and depression in soldiers deployed in Iraq. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:735–741. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10091309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning M, Holmes EA, Charles M, Cowen PJ, Harmer CJ. Using attentional bias modification as a cognitive vaccine against depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;72:572–579. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DA, Beck AT. Scientific foundations of cognitive theory and therapy of depression. John Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:186–193. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daros A, Zakzanis KK, Ruocco AC. Facial emotion recognition in borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:1953–1963. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJ, Dobson KS, Ahnberg JL. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsche A, Dahme B, Gotlib IH, Joormann J, Magnussen H, Watz H, Nutzinger DO, von Leupoldt A. Specificity of cognitive biases in patients with current depression and remitted depression and in patients with asthma. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:815–826. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Hammen CL. Psychological aspects of depression: Toward a cognitive-interpersonal integration. Oxford, U.K: Wiley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Krasnoperova E, Yue DN, Joormann J. Attentional biases for negative interpersonal stimuli in clinical depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:127–135. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakamata Y, Lissek S, Bar-Haim Y, Britton JC, Fox NA, Leibenluft E, Pine DS. Attention bias modification treatment: A meta-analysis toward the establishment of a novel treatment for anxiety. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallion LS, Ruscio AM. A meta-analysis of the effect of cognitive bias modification on anxiety and depression. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:940–958. doi: 10.1037/a0024355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Interpersonal stress and depression in women. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;74:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Metalsky GI. A prospective study of an integrative interpersonal theory of depression: A naturalistic study of college roommates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:778–788. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Gotlib IH. Selective attention to emotional faces following recovery from depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:80–85. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappenman ES, MacNamara A, Proudfit GH. Electrocorticol evidence for rapid allocation of attention to threat in the dot-probe task. Social, Cognitive, and Affective Neuroscience. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsu098. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessing LV, Hansen MG, Andersen PK, Angst J. The predictive effect of episodes on the risk of recurrence in depressive and bipolar disorders a lifelong perspective. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;109:339–344. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0447.2003.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1993;29:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90026-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod C, Mathews A, Tata P. Attentional biases in the emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95:15–20. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K, Bradley BP, Williams R. Attentional bias in anxiety and depression: The role of awareness. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;34:17–36. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1995.tb01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K, Bradley BP. Attentional bias in generalized anxiety disorder versus depressive disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2005;29:29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Price RB, Kuckertz JM, Siegle GJ, Ladouceur CD, Silk JS, Ryan ND, Dahl RE, Amir N. Empirical recommendations for improving the stability of the dot-probe task in clinical research. Psychological Assessment. doi: 10.1037/pas0000036. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmukle SC. Unreliability of the dot probe task. European Journal of Personality. 2005;19:595–605. [Google Scholar]

- Sears CR, Newman KR, Ference JD, Thomas CL. Attention to emotional images in previously depressed individuals: An eye-tracking study. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 2011;35:517–528. [Google Scholar]

- Staugaard SR. Reliability of two versions of the dot-probe task using photographic faces. Psychology Science Quarterly. 2009;51:339–350. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens S, Rist R, Gerlach AL. Eye movement assessment in individuals with social phobia: Differential usefulness for varying presentation times? Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2011;42:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone LB, Uhrlass DJ, Gibb BE. Co-rumination and lifetime history of depressive disorders in children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:597–602. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, Tanaka JW, Leon AC, McCarry T, Nurse M, Hare TA, Nelson C. The NimStim set of facial expressions: Judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Research. 2009;168:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veague HB, Hooley JM. Enhanced sensitivity and response bias for male anger in women with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2014;215:687–693. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waechter S, Nelson AL, Wright C, Hyatt A, Oakman J. Measuring attentional bias to threat: Reliability of dot probe and eye movement indices. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2014;38:313–333. [Google Scholar]

- Wells TT, Beevers CG. Biased attention and dysphoria: Manipulating selective attention reduces subsequent depressive symptoms. Cognition and Emotion. 2010;24:719–728. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World health statistics 2012. World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Ding Z, Dai T, Peng F, Zhang JX. Attention Bias Modification training in individuals with depressive symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.08.005. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]