Abstract

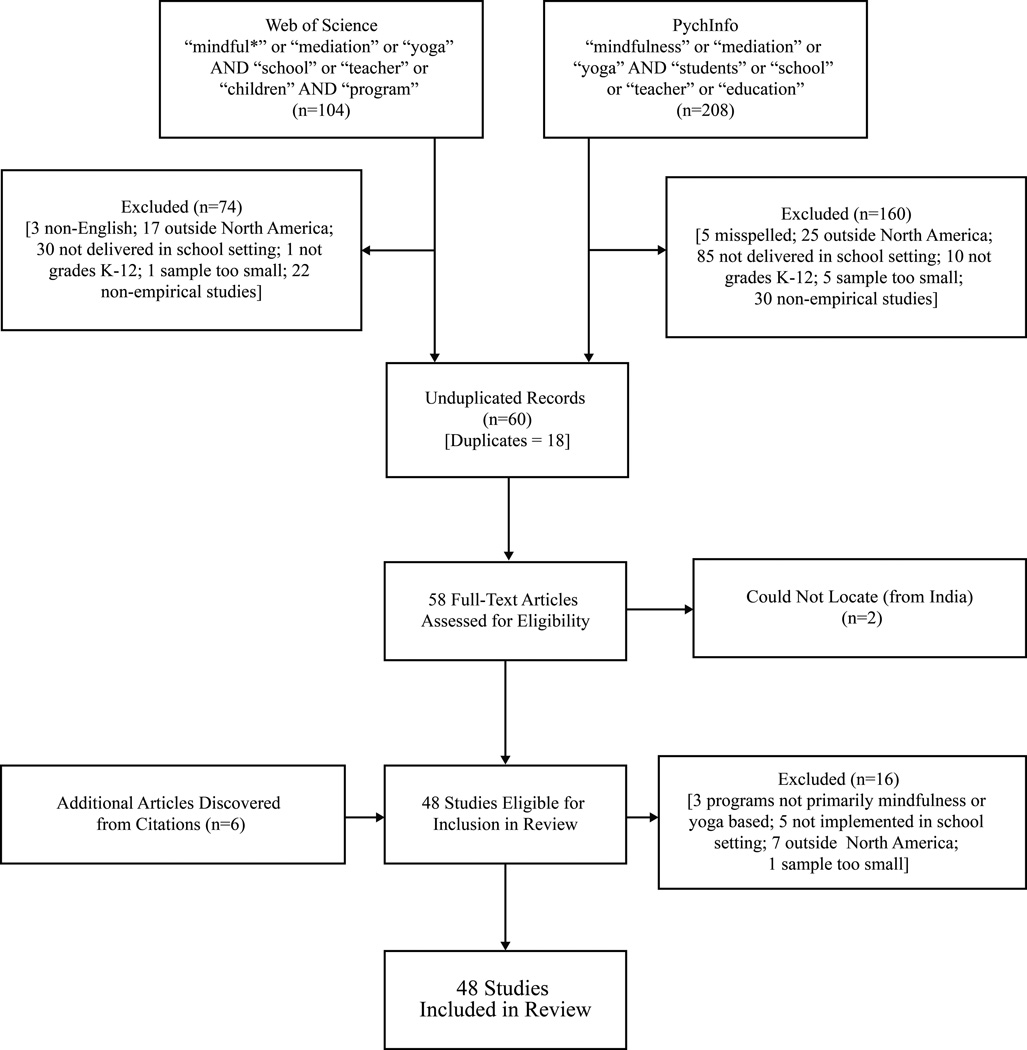

As school-based mindfulness and yoga programs gain popularity, the systematic study of fidelity of program implementation (FOI) is critical to provide a more robust understanding of the core components of mindfulness and yoga interventions, their potential to improve specified teacher and student outcomes, and our ability to implement these programs consistently and effectively. This paper reviews the current state of the science with respect to inclusion and reporting of FOI in peer-reviewed studies examining the effects of school-based mindfulness and/or yoga programs targeting students and/or teachers implemented in grades kindergarten through twelve (K-12) in North America. Electronic searches in PsychInfo and Web of Science from their inception through May 2014, in addition to hand searches of relevant review articles, identified 312 publications, 48 of which met inclusion criteria. Findings indicated a relative paucity of rigorous FOI. Fewer than 10% of studies outlined potential core program components or referenced a formal theory of action, and fewer than 20% assessed any aspect of FOI beyond participant dosage. The emerging nature of the evidence base provides a critical window of opportunity to grapple with key issues relevant to FOI of mindfulness-based and yoga programs, including identifying essential elements of these programs that should be faithfully implemented and how we might develop rigorous measures to accurately capture them. Consideration of these questions and suggested next steps are intended to help advance the emerging field of school-based mindfulness and yoga interventions.

Keywords: mindfulness, yoga, fidelity, implementation, review, school-based intervention

Introduction

In the current climate of enthusiasm for school-based mindfulness and yoga programs, research efforts have aimed primarily to evaluate program impacts on teacher and student outcomes. Indeed, a number of reviews and meta-analyses have now summarized the growing evidence base for effects of school-based mindfulness and yoga (Davidson & Mind and Life Education Research Network 2012; Meiklejohn et al. 2012; Serwacki & Cook-Cottone 2012). Assessing intervention outcomes is critical to testing program efficacy and gaining support and funding for these programs (Greenberg & Harris 2012; Weare 2013). Outcomes assessment alone, however, is not sufficient to build a rigorous evidence base for school-based contemplative practices. The systematic study of fidelity of program implementation (FOI) is needed to provide a more robust understanding of the core components of mindfulness and yoga interventions for youth, their potential to improve specified teacher and student outcomes, and our ability to implement these programs consistently and effectively across time and in diverse school settings (Davidson & Mind and Life Education Research Network 2012; Greenberg & Harris 2012).

FOI is a multi-dimensional construct that refers to the degree to which intervention delivery adheres to the intervention developers’ model (Dane & Schneider 1998). Whereas traditional intervention outcomes research focuses on program effects (the dependent variables), the study of FOI refines our understanding of the core elements that constitute a given program (the independent variable) and their relationship to program outcomes. In order to study FOI, researchers and program developers must first identify the key constituent parts of an intervention and articulate how these components are anticipated to create desired outcomes. They must then develop reliable and valid measures of FOI and establish measurable criteria for implementation integrity. These criteria can be used in subsequent research to examine empirically whether variation in the implementation of core components is systematically related to particular outcomes across replication trials (Feagans Gould et al. 2014).

Why is Fidelity of Implementation Important?

Assessing fidelity of implementation is important to our understanding of whether and how school-based mindfulness programs work for several reasons. First, what actually gets implemented in real-world settings, like schools, may vary from study to study, even within the same program. Therefore evidence-based practice needs a means of evaluating whether a program is being implemented as intended (Carroll et al. 2007). Evidence indicates marked variation in implementation fidelity both across and within youth psychosocial prevention and promotion programs focused on mental and physical health (Durlak & Dupre 2008). It is highly likely that similar variability in implementation fidelity exists for mindfulness-based programs. Such variation will become more apparent as an increasing number of mindfulness-based programs are implemented and larger studies are conducted.

Second, the degree to which programs are implemented with fidelity in real-world settings directly informs the conclusions we can make about the effectiveness of a single program or school-based mindfulness programs more generally (Carroll et al. 2007). Durlak and Dupre reviewed over 500 studies of promotion and prevention programs for youth and adolescents, including 5 meta-analyses, and concluded that, “Achieving good implementation not only increases the chances of program success in statistical terms, but also can lead to much stronger benefits for participants” (2008, p. 334). Indeed the magnitude of mean effect sizes was at least two to three times higher when programs were carefully implemented and free from serious implementation problems, particularly when fidelity or dosage were assessed. This is consistent with an emerging body of evidence that suggests program fidelity leads to better outcomes and program outcomes are sensitive to variations in implementation fidelity (Kutash, Cross, Madias, Duchonowski, & Green 2012). In addition, assessing fidelity of implementation guards against making what is known as a Type III error - the incorrect conclusion that a program itself is not effective, when in fact poor outcomes are the result of shortcomings in implementation (e.g., the instructor did not have time to cover all the curriculum components) (Domitrovich & Greenberg 2000).

Third, assessing program fidelity can help move us toward an understanding of how programs work and the “active ingredients,” or drivers, of program effects. Although mindfulness and yoga programs all include contemplative practices that focus on anchoring attention in the present moment, programs vary widely in the specific forms of mindfulness practice they teach, in program duration and dosage, and in the types and characteristics of school-based populations they target (e.g., students and/or teachers, developmental stage or grade level, socioeconomic status) (Greenberg & Harris 2012; Meiklejohn et al. 2012). Programs are likely to produce different levels of impact based on program features and characteristics of the target population. Particular practices (e.g., breath work) or program components (e.g., assigned homework) also may be differentially effective in producing outcomes. Thus, FOI measures are critical for developing our understanding of which mindfulness practices or program components are most effective, for whom, and under which conditions.

Finally, assessing FOI can help facilitate program improvement and refinement. FOI findings can identify which aspects of a program are contributing to its efficacy and which aspects are not, potentially informing changes in intervention content. For instance, if practice of guided mindfulness reflections is found to predict particularly robust intervention gains, program developers may wish to increase the frequency with which this skill is practiced throughout the program. FOI findings can also inform decisions about which program aspects may require modification to overcome implementation challenges and facilitate delivery as intended. For instance, if program instructors consistently have difficulty fully covering curriculum material, program developers may decide that the curriculum needs to be pared down or that more intervention sessions are needed.

How do we study FOI?

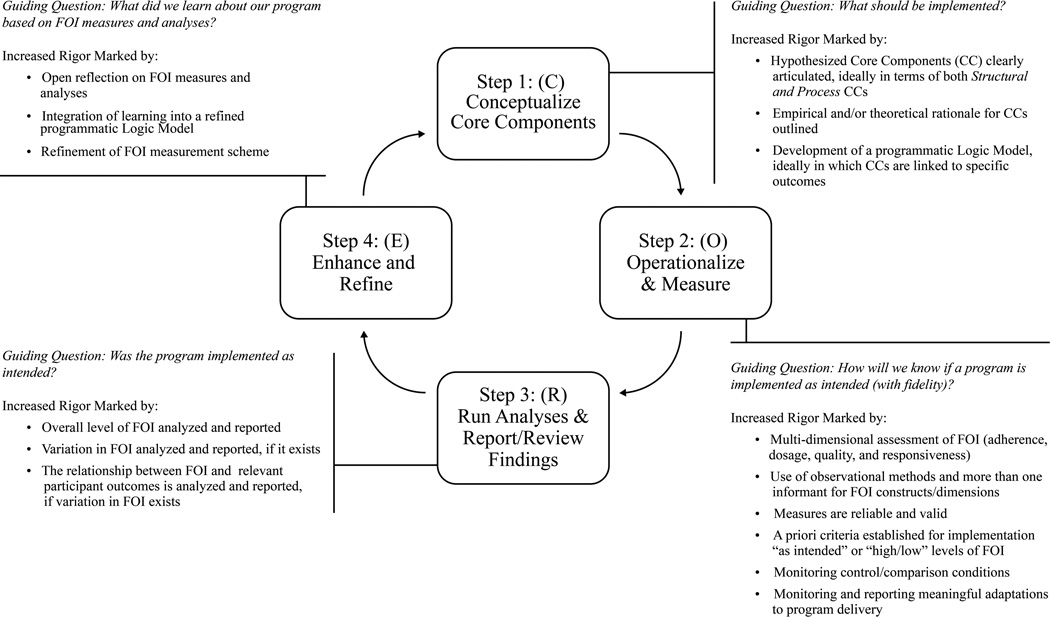

Approaches for assessing and analyzing FOI vary based on program and research goals, as well as the nature of the program and context of implementation. Conceptualizations of FOI span many disciplines including mental health, prevention research, education, criminal justice, public health and policy (Burkel et al. 2011; Century, Rudnick, & Freeman 2010; Caroll et al. 2007; Durlak & Dupre 2008; O’Donnell 2008; Fixsen, Blase, Naoom, & Wallace 2009). Although differences across these frameworks merit attention, their core aspects are fairly similar. This review references a general framework based on the Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycle (Deming 1986) and consistent with leading FOI conceptualizations (Century et al. 2010), which our team has discussed elsewhere in the context of our school-based mindfulness research (Feagans Gould et al. 2014). We have termed this framework the CORE cycle, as it involves the following steps: (C) Conceptualize core components; (O) Operationalize and measure; (R) Run analyses and review; and (E) Enhance and refine. Thus, we conceptualize the study of FOI as a four-step, iterative process that leads, over time, to a more refined theory of change, greater knowledge about the effective or core components of a program, and more rigorous measures of implementation integrity (see Figure 1). Below we briefly outline the four steps and their relevance to the study of FOI in school-based mindfulness and yoga programs.

Fig. 1.

The CORE Process Model for Assessing Fidelity of Implementation (FOI)

Step 1: Define program core components and their relation to hypothesized outcomes

The aim of this step is to answer the question: What should be implemented? To judge whether a program is implemented faithfully, we must first identify the core components, also referred to as critical components (see Ruiz-Primo 2005; Century et al. 2012) that comprise the program. Core components are -- “the most essential and indispensable components of an intervention practice or program” (Fixen et al. 2005 p.24)—and the backbone of program fidelity. Core components have been conceptualized as being of two types: structural components (the content or activities to be delivered, say, as part of a manual) and process components (the manner in which content should be implemented, for instance, the modeling of compassionate responses by program instructors) (Century et al. 2012). Identification of core components transforms an intervention from a “black box” to a set of elements that can be measured and assessed.

Development of a programmatic logic model--sometimes called a theory of change—is also critical and goes hand in hand with specification of core program components. A logic model guides measurement and analysis by specifying how each program core component, or combinations of components, should lead to hypothesized outcomes. For instance, program developers may predict that focused attention training through awareness of the breath will enhance capacities for self-regulation, leading to downstream improvements in students’ behavior and performance in class. A logic model generally draws on relevant theoretical perspectives and empirical findings from the literature, e.g., an evidence base supporting links between self-regulation and classroom behavior. Ideally, there is logic not only behind specification of the hypothesized core components but also to support other aspects of a program like the sequencing of intervention activities and program dosing.

Step 2: Operationalize and measure the FOI of core program components

The aim of this step is to answer the question: How will we know if a program is implemented with fidelity? Once a program’s core components have been articulated, an objective assessment system is needed to monitor fidelity of implementation to these core components (Durlak 1998; Domitrovich & Greenberg 2000). There are four commonly agreed-upon dimensions of fidelity (Dane & Schneider 1998; Dusenbury, Brannigan, Falco, & Hansen 2003): 1) Adherence - the extent to which the core components were implemented as designed; 2) Dosage - the amount of the intervention received by participants; 3) Quality - the extent to which an instructor delivered program content as intended; and 4) Responsiveness - the extent to which participants were engaged in the program. Assessing multiple dimensions of fidelity is preferable, not only because it offers a more well-rounded assessment of these various aspects of FOI, but also because evidence shows that each has the potential to be a critical dimension fostering participant outcomes (Durlak & Dupre 2008).

Measures of each dimension of FOI should be reliable and valid, using the same standards applied to intervention outcome measures (Domitrovich & Greenberg 2000; O’Donnell 2008). Collecting FOI data from multiple reporters is desirable, particularly using “objective” measures, such as observational coding of intervention sessions by coders because these are typically more highly correlated with program outcomes than instructor-reported data, which are prone to bias (Dane & Schneider 1998). Along with developing reliable and valid measures, a priori criteria for what constitutes implementation “as intended” or “not as intended” must be defined and operationalized in terms of the measures being used. For example, it is helpful to create a cut-off for the number of sessions a participant must attend or the extent of training a teacher must receive in order to qualify as a sufficient “dose.” Another way to operationalize as intended is to create categories of “low,” “medium,” and ‘high” dosage. The important point is that these criteria are defined a priori within a single study, so that they are theoretically informed. Across replication trials, however, specific cut-offs can be empirically informed by results.

Two final aspects of rigorously assessing FOI are the monitoring of control/comparison conditions and reporting adaptations made to the program during implementation (Durlak & Dupre 2008). Monitoring control/comparison conditions involves describing the nature and amount of services received by members of comparison conditions because it is often incorrectly assumed that controls do not receive any services, but this is almost never the case in school-based studies (Durlak 1985). In order to fully understand control-comparison condition differences, FOI data can be collected to inform differential uptake of the IV and therefore a more accurate picture of the unique value of an intervention. In addition, collecting data on what meaningful adaptations were made to program delivery is important as sometimes such adaptations have been found to have adverse effects on outcomes, and other times adaptations based on context or the specific characteristics of recipients have been found to improve impacts (Durlak & Dupre 2008).

Developing and refining valid and reliable measures for each of the four dimensions of FOI is a challenging process that takes time and may also require additional resources, such as recording of intervention sessions and training independent coders. Given the iterative nature of the process, FOI measures for a given intervention have potential to improve following initial formative work, as the program components are increasingly refined and as implementation issues are better understood.

Step 3: Analyze FOI data and report findings

This step may address a variety of questions, including: Was the program implemented as intended? If variation in implementation exists, to what extent are outcomes affected? It is important for researchers to report the level of FOI in studies on school-based mindfulness and yoga programs to document the implementation quality associated with particular outcomes and to identify potential variation in program implementation across intervention instructors and/or sites. If variation exists, researchers should gauge whether FOI was so low that participants did not in fact receive what would be considered a minimally effective dose of the program. If there is sufficient variation in FOI, evaluators can also categorize intervention groups, classrooms, or schools by levels of FOI to test whether variation is related to outcomes. When such analyses are performed they help us answer important questions like “what is the dosage or frequency needed to produce certain level of outcomes?”

Step 4: Enhance and refine the logic model and FOI measures based on findings from FOI data

This step aims to address the question, What did we learn about a program and FOI measures? Researchers should ideally use FOI data to reflect on their hypothesized core components and logic model. Rigorous measurement and analysis of FOI can facilitate the iterative learning cycle of program development. FOI analyses within a given study can refine understanding of why and under what conditions a program works. Across programs, such analyses can move the field towards identification of best practices or common active ingredients, a key next step in the growing new field of school-based mindfulness and yoga interventions research.

Aims of the current review

Given the importance of FOI for building a robust and informative evidence-base, we reviewed the current state of the science with respect to inclusion and reporting of FOI in studies on school-based mindfulness and yoga interventions. We focused on the extent to which: 1) hypothesized program core components and logic models are specified in the literature; 2) FOI is being rigorously assessed and reported; and 3) the relationship between FOI and program outcomes is being reported. We hope this paper will offer useful suggestions for school-based mindfulness researchers beginning to tackle the challenges of FOI measurement and analysis. Synthesizing FOI data across studies also provides an opportunity to reflect on the commonalities across specified core components and logic models and the utility of particular FOI measures. Consideration of these questions is intended to help advance the emerging field of school-based mindfulness and yoga interventions.

Method

Information sources and searches

To identify potentially relevant articles, we searched two databases, PsycInfo and Web of Science, from their inception to May 2014 using combinations of the terms mindfulness, mindful, yoga, meditation, school, education, program, students, and teachers. We also searched reference lists in relevant review articles.

Study selection

To be selected for inclusion, a study was required to meet the following criteria: 1) assessment of a program for students and/or teachers whose primary content was mindfulness-based practices or yoga-based movement, 2) program delivery in a school setting--either during or after the school day—in grades kindergarten through twelfth grade (K-12), 3) program delivery in the United States or Canada, 4) Experimental, Quasi-experimental, or single group study designs with a sample size of greater than five participants (consistent with Meiklejohn et al. 2012), 5) publication in a peer-reviewed journal or book chapter, and 6) publication in English. We chose to focus on mindfulness and yoga-based programs because these are the most widely-used forms of contemplative practices secularly implemented and studied in school settings (Greenberg & Harris 2012). Our focus on grades K-12 was motivated by the focus of this special issue on school-based mindfulness programs for youth. We chose to limit our review to programs delivered in North America as we anticipated that these programs and school settings would be most comparable and thus most amenable to this initial attempt at synthesis of FOI measurement. Questions regarding whether or not a study met eligibility criteria were discussed among two or more co-authors until consensus was reached. In three instances when it was unclear if a study met inclusion criteria based on the full text of an article, the lead author contacted the corresponding author to provide additional details.

Data abstraction

The lead author abstracted the following data from each study included in the review within the following broad domains:

Program and study characteristics included primary program focus, program approach, program session length, frequency, duration, and format, grade-level of school setting, when and where a program was implemented within the school setting, study design, sample size, and number of schools and classrooms in which a program was implemented. These variables capture the potential variation in program focus and implementation methods as well as the kinds of studies conducted to date. Primary program focus refers to whether the intervention content consisted mostly of “Meditation,” “Yoga;” or “Combined Meditation and Yoga.” In order for a program to be categorized as “primarily meditation,” the primary program practices and components, as described in the article, included forms of meditation such as open-monitoring, focused attention, and/or loving kindness/compassion practices (see Ricard, Lutz, & Davidson 2014; Roeser & Pinela 2014 for further discussion of forms of meditation). For a program to be “primarily yoga,” the predominate program practices and components, as described in the article, included yoga –based physical movements (e.g. asanas) and embodied practices. For programs categorized as “combined meditation and yoga,” the program focus was relatively equally distributed across meditation and yoga practices and components. Program approach is based on the major approaches outlined by Meiklejohn and colleagues (2012) to characterize school-based mindfulness programs as directly targeting students, indirectly delivering to teachers or delivering program components to both students and teachers.

Theoretical rationale underpinning core program components included whether a study articulated the core or potentially essential program components and theoretical underpinnings for the program being evaluated. For this domain, we extracted the language used to describe the main program components and any rationale for these components, coded whether key or core program components were articulated (as opposed to simply describing components of the program without any reference to their centrality to program theory), as well as whether or not a logic model was included.

FOI rigor and reporting categorized whether a study assessed each of the four dimensions of FOI (i.e. adherence, quality, dosage, and responsiveness), what measures were used to assess each dimension, if multiple measures were used to assess a single dimension, if reliability or validity of measures were assessed, if any a priori criteria for “high” or “low” levels of FOI were set, if FOI was monitored in the control/comparison condition, and if and what adaptions made during implementation were reported. We also recorded whether and how levels of FOI were reported and whether there was any variation in FOI across different instances of program delivery in the study.

FOI associations with outcomes categorized whether a study assessed the association of FOI aspects with outcomes and, if yes, briefly summarized the findings.

Results

Our literature search identified 312 citations, from which 60 articles were retrieved and 48 judged to meet study criteria and retained (see Figure 2). Additional details about the programs and studies included as well as select categories of data extracted are included in Appendix A.

Fig. 2.

Flow Diagram of Relevant Article Identification and Selection

Appendix A.

List of Programs and Studies Reviewed and Select Categories of Data Extracted

| Program | Study | Delivery Approach |

Study Design | Session Delivery | FOI Dimensions Assessed and Measures Used | FOI

Cut-Offs Established |

FOI Reported | Linked to Outcomes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program Name |

Core

Components (CC) Articulated & Logic Model (LM) Included |

Citation |

Program

targets Students, Teachers, or Both |

Design (RCT;

QED, Single Group); Level of Assign (School or Class); & # IUs (intervention units) |

Total #

Sessions Delivered, Weeks, and Length |

Program Adherence | Program Quality | Participant Dosage | Participant Responsiveness |

Were a priori

cut- offs established? |

Was any aspect of FOI reported? If so, what? |

Was

relationship between FOI and participant outcomes assessed? |

| Learning

to BREATHE |

CC -

Yes LM -No |

Metz et. al. (2013) | Teachers |

Design: QED

pre- post, with instruction- as-usual comparison Level: School IU: 1 school |

Total #: 6

thematic lessons broken up and delivered over 18 sessions Weeks 16 Session Length 15–25 minutes at beginning of class |

Measures. teacher

logs (unclear # of items; at each lesson, however very few completed) & observations by program staff (unclear number of items - checklist; 5% of all sessions) |

Measures. teacher

logs (unclear number of items) & observations by program staff (teacher enthusiasm and preparedness) |

Unclear if Assessed |

Measures.

Observations (qualitative) |

Not Reported | Adherence/Quality/Responsiveness:

Descriptive statement: "Observations indicated lesson adherence, teacher, enthusiasm and preparedness and high student engagement" No teacher logs reported |

No |

| Broderick &

Metz (2009) |

Students |

Design: QED

pre- post, with portion of junior class as comparison Level: Classroom IU: 1 school - 7 sections of health class |

Total #: 6

lessons per group (7 groups) Weeks: @ 5 (could be as few as 3) Session Length: 32–43 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures. How

oftern practiced mindfulness outside of class (qualitative and then catgorized as 4 or more days/week, once a month to 3 days a week, and none) |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Dosage. 65% of students

reported practicing some mindfulness techniques otuside of class For those practicing 4 or more days per week outside of class, compared to those who only practiced in class, overall somatic complaints were reduced & specific somatic complaints of dizziness and feeling over-tired increased. |

Yes | ||

| Inner Kids Program |

CC- No LM - No |

Flook et al. (2010) | Students |

Design: RCT

with active reading period control Level: Student with block randomization stratified by classroom, gender, and age IU: 32 students |

Total #: 16

sessions Weeks: 8 Session Length: 30 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Adherence. Number of sessions delivered | No |

| Mindfulness Education (ME) Program |

CC-Yes LM - No |

Schonert-Reichl and Lawlor (2010) |

Teachers |

Design: QED,

pre- post Level Classroom IU: 6 Classrooms |

Total #

9–10 lessons + (daily mindfulness exercises 3 times a day for up to 3 minutes) Weeks: 9–10 (final week optional) Session Length: 40–50 minutes |

Measures. Teacher

Daily Diary track daily implementation of core exercises; extent to which implemented program lessons each week, and # of ways integrated into classroom curriculum and practices |

Not Reported | Not

Reported (although classify the adherence measures to the left as "dosage") |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Adherence. Mean and range across

lessons: teachers reported implementing components of lessons 75% of time, indicating a moderate to high level of average implementation Average proportion of program core mindful exercises (breathing practices) completed by week. Included a table for this. Range of implementation of core exercises was 73%– 100% with an average of 87% across 9 weeks. 100% of teachers reported that they implemented extension activities within classrooms (not clear what this means) |

No |

| Holistic

Life Foundation |

CC-

No LM - Yes |

Mendelson et al. (2010) |

Students |

Design: RCT w/

wait- list control (not active) Level: School IU: 2 elementary schools |

Total #: 48

sessions Weeks: 12 Session Length: 45 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures.

Student Attendance (but don't outline how assessed) |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Dosage. Percent of students at

each school who attended at least 75% of sessions. 73.5% at one school and 40% of students at another. Teacher focus group data indicated that some teachers prevented students from attending as form of punishment for poor in-class behavior |

No |

| Feagans Gould et

al. (2012) |

Students |

Design: RCT w/

wait- list control (not active) Level: School IU: 2 elementary schools |

Total #: 48

sessions Weeks: 12 Session Length: 45 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | ||

| CARE: Cultivating Awareness & Resilience in Education |

CC-

Yes LM - Yes |

Jennings et al. (2013) | Teachers |

Design:

RCT Level: Teacher IU 27 teachers |

Total #: 5

full-day sessions, plus 2 coaching calls, plus local group support activities Weeks: approx. 12 weeks Session Length: Varied: Full-day sessions (6 hours); Coaching calls (20–30 minutes) |

Measures.

Facilitators Record sheet completed at end of each session by facilitator and trained observer. Don't say anything specific about number of items whether quant or qual or how assessed at all. |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Adherence. Desriptive statement:

"Because the facilitators were working directly from the materials they created, the program was delivered with a high degree of fidelity (100%)" However, do not report what measures were comprised of or how compiled and cross-validated to get at 100% fidelity |

No |

| Jennings et al. (2011) | Teachers |

Study

1 Design: Single group pre-post Level: Teacher IU: 31 Study 2 Design: RCT Level: Classroom (student teacher/ mentor teacher pairs) IU: 21 |

Total #: 4 or

5 full-day sessions, plus 2 coaching calls Weeks: approx. 5 weeks Session Length: Varied: Full-day sessions; Coaching calls (20–30 minutes) |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | ||

| mMBSR (modified mindfulness- based stress reduction) |

CC- No LM - No |

Flook et al. (2013) | Teachers |

Design: RCT

with wait-list control - 4 schools total Level: Classroom/teacher IU: 10 teachers/classrooms |

Total #: 9

sessions (26 hours total) Weeks: 8 Session Length: 2.5 hours per week for 8 weeks plus a day-long immersion for 6 hours |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures.

Weekly practice logs in which participants recorded Mindfulness practice compliance (or number of minutes per day spent engaging in formal (e.g. sitting meditation) and informal (e.g. brief moments of mindfulness) mindfulness practice. |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Dosage. Reported the average

minutes per day in formal and informal practice as well as frequency of mindfulness practice. Specifically, participants reported spending on average 21.7 min (SD=13.8) per day in formal practice and 7.5 min (SD=4.7) per day in informal practice. During 8-week course, participats reported engaging in formal practice 83.7% of days (M=46.9; SD=7.1) and informal practice 88.7% of days (M=49.7; SD=4.4). |

No |

| MM (Mindfulness Meditation) |

CC- No LM - No |

Beauchemin et al. 2008 |

Both Students

& Teachers |

Design:

Single group, pre-post Level: Classroom IU 4 classes (2 teachers & 34 students) |

Total #

approx. 27 Weeks: 5 Session Length 5–10 minutes at beginning of class period (# of class periods per day not specified) plus two 20 minute instructional sessions. |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No |

| Cultivating Emotional Balance |

CC- No LM - No |

Kemeny et al. (2012) | Teachers |

Design: RCT,

pre- post, 5-month follow- up Level: Teacher IU: 41 teachers |

Total #: 4

sessions Weeks 8 Session Length: 4 All- Day & 4 Evening sessions (total of 42 hours of training); recommended 25 min/day home practice |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures. Weekly

online self-reported logs to assess # of minutes of meditation practiced each day. Created varaible: total days mediated 20 min or more across 8-week period. |

Not Reported | No | Dosage. The greater the number of

days individuals reported practing meditation (20 min/day or more), the lower their trait anxiety and the higher their mindfulness at posttraining, but these did not occur with other self-report measures. Greater meditation practice associated with diminished blood pressure reactivity during lab task, compared with those who practiced less, & decreased Diastolic Blood Pressure during speech and math portions of Trier Social Stress Test at follow- up as well as decreased Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia in response to the math task at follow-up Greater mediation practice was not associated with compassionate responding or social behavior on marital task. |

Yes |

| MIL: Moving into Learning |

CC- Yes LM - No |

Klatt et al. (2013) | Students |

Design:

Single group, pre-post & follow-up Level: Classroom IU: 2 classrooms (41 students) |

Total #: 8

weekly sessions; 32 daily sessions Weeks: 8 Session Length: 45 minutes for weekly sessions; 15 minutes for daily sessions |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No |

| Inner Resilience Program (IRP) |

CC- No LM - No |

Lantieri et al. (2011) | Both Students

& Teachers |

Design:

RCT Level: Classroom across many schools (unsure #) IU: 29 teachers & 471 students in their classrooms |

Total #: 27

weekly yoga sessions; 9 monthly NTIL sessions; 1 weekend-long retreat Weeks 27–36 weeks across components Session Length: Weekly yoga (75 minutes); Monthly NTIL meetings (2.5 hours each); 2-day weekend residential retreat |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No |

| SMART-in- Education (Stress Management & Relaxation Techniques) Program |

CC- Yes LM - Yes |

Roeser et al. 2013 | Teachers |

Design: RCT, with

3- month follow-up Level: Teacher IU: 54 Teachers |

Total #:

11 Weeks: 8 Session Length: Doesn't say, but total of 36 contact hours across 11 sessions |

Not

Reported (although assert adherence was controlled for because program developer implemented at all sites) |

Measures. Evaluation

survey participants filled out at end of program. Instructor domain-specific expertise, genuineness, effectiveness at presenting material, and trustworthiness on 5-pt. Likert scale. |

Measures.

Facilitator- reported attendance at weekly sessions as well as teacher completion of program. Daily mindfulness practice journal. Teachers self- reported minutes of daily practice |

Not Reported | Yes. Program completer had to attend at least 8 of the 11 sessions. Suggested 15/min a day of home practice. |

Dosage. Those who didn't

drop out attended 92% of sessions. Absences ranged from 0–4 with 87% of participants completed the program by attending 8 or more of the 11 sessions. Amount of home practice examined for the 60% of participants who returned daily practice journals. Teachers reported avg. of 16 min. of practice/day (Canadian sample) and 15 min. of practice/day (U.S. sample). This showed compliance w/ 15-min a day home practice Quality. On average, participants "strongly agreed" that instructor demonstrated good knowledge of the subject matter (expert knowledge, M=4.98, SD=.14); was a "good role model for what was being taught" (genuineness, M= 4.94, SD=.24), was "effective in presentation of material" (effectiveness, M=4.83; SD=.38), and participants "developed a faith in their ability to trust & learn from the instructor" (trustworthiness, M=4.88, SD=.48). Instructions for home practice very clear and useful. |

No |

| CC- No LM - No |

Benn et. al. (2012) | Teachers |

Design: RCT with

2- month follow-up Level: Teacher/Parent IU: 31 participants (12 parents and 19 educators) |

Total #: 11

sessions (2 times per week for a total of 36 hours) Weeks: 5 Session Length: 2.5 hours ( 9 sessions) & 6 hours (2 sessions) |

Measures. Research

assistant observed sessions and provided qualitative feedback on program fidelity (instructor adherence to format, content, and process of delivery) during weekly research meetings. |

Measures.

Participant responses to open-ended questions on individual session evaluations and ratings of overall instructor quality at the conclusion of the program. |

Measures.

Program completion and attendance. Unclear what determines program completion. Participant-reported estimates of frequency of home practice. |

Not Reported | No | Dosage. Results showed that all

but 1 participant competed the MT program and all attended most of the sessions (M=9.9 sessions, range 7–11 sessions). Quality. Participants indicated high levels of satisfaction with the program in terms of quality of instruction, content, and structure. They rated the level of instruction as either a 4 or 5 on a 5-point scale. Adherence. Qualitative reports by RAs suggest high-quality instructor adherence to the format, content, and process of curriculum delivery. Participants reported an average of 10 minutes of formal mindfulness home practice per day. |

No | |

| MBSR adapted for urban youth |

CC- No LM - No |

Sibinga et al. (2013) | Students |

Design: RCT, with

3- month follow-up, active control - health education program Level: Student IU: 1 school (22 students) |

Total #: 12

sessions Weeks: 12 Session Length: 50 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No |

| Adapted MBSR Program |

CC- No LM - No |

Frank et al. (2013) | Teachers |

Design QED,

pre- post Level: School IU 1 School - 18 instructors, specialists, and administrators |

Total #

8 Weeks: 8 Session Length: 2 hours (weekly sessions) plus 25–30 min of daily practice (at home) 6 days/wk. |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures. Daily logs

- no other details on what those are. |

Not Reported | No | Dosage. MBSR participants

practiced mindfulness meditation outside class on average 4 times per week (M=3.9; SD=1.5) for a mean of 22.6 minutes (SD=4.6) per practice period over the 8 week course. |

No |

| Transformative Life Skills (TLS) |

CC- No LM - No |

Frank et al. (2014) | Teachers |

Design

Single group, pre-post Level: Student IU: 49 students |

Total # 48

lessons Weeks: Approximately 12 Session Length: 30 minutes (3–4 days a week) |

Measures.

Instructor-reported lesson component completion checklist at the end of each lesson. Say supervision of instructors by program developers, observation, and review of these checklists were used to monitor fidelity throughout implementation. |

Measures.

Instructor- reported reflection on quality of lesson implementation. |

Not Reported |

Measures.

Instructor-reported overall level of student engagement (as a whole not per student) at the end of each lesson. |

No | Overall fidelity: All lessons

were implemented with greater than 80% fidelity (not sure how calculated - if refers to adherence or adherence & quality) |

No |

| Mindfulness Meditation (MM) Program |

CC-

No LM - No |

Wisner (2013) | Students |

Design Single

group Level: Student IU: 35 Students in a single alternative high school (total enrollment of school was 36 students) |

Total #: 29

sessions Weeks 8 Session Length: Varied (1 30-min intro session, plus 30-min sessions 2 times per week; plus 10 minute sits 2 times per week in weeks 3–8) |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures.

Participant reported use of practice CD and home practice. |

Not Reported | No | Dosage. Ten out of 35 (approx.

30%) students reported using practice CD at home, with most of these students using the CD once, twice, or three times. One student used CD on regular basis. Five out 35 students (approx. 15%) reported that they practicd meditation at home without the CD and 2 students reported using meditation on a regular basis while 3 students reported trying meditation on two or three occassions. |

No |

| Wisner et al. (2013) | Students |

Design:

Single group, pre-post Level: student IU: 28 students from 1 alternative high school (78% of student body) |

Total #: 29

sessions Weeks: 8 Session Length: Varied (1 30-min intro session, plus 30-min sessions 2 times per week; plus 10 minute sits 2 times per week in weeks 3–8) |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No | ||

| RISE Program | CC- No LM - No |

Winzelberg &

Luskin (1999) |

Teachers |

Design: RCT, with

8- week follow-up Level: Teacher IU: Unclear - but probably 8 teachers in training (6 couldn't attend training so assigned to wait-list control; remaining 15 randomized to exp. Or control) |

Total #:

4 Weeks: 4 Session Length 45- minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures.

Self-report questionnaire administered at follow-up (8 weeks after). Asked frequency with which practiced techniques in an average week during the program and at the time of follow- up (both for mediation and the 3 corollary techniques) |

Not Reported | No | Dosage. During program,

participants reported practicing meditation an average of 3 times/week. At follow-up, 1/2 of the participants reported they were no longer practicing the meditation, but most were still practicing the corollary techniiques. They reported remimbering to "slow down" and "do one thing at a time" several times a week. Overall, use of all techniques decreased from an average of 13.4 at post-test to 9.1 at follow-up. Includes a Table of treatment group practice frequency per week over the course of the program. |

No |

| Mindful

Schools (K-5 Curriculum) |

CC-

No LM - No |

Black &

Fernando (2013) |

Students (with small Teachers component) |

Design: RCT

(no control) either MS or MS + 7 additional sessions Level Classroom IU: 17 classrooms total (409 students) |

Total #: 15

(MS) or 22 (MS +); brief (2 min) practices on non-session school days Weeks: 5 (MS) or 12 (MS +) Session Length: 15 min., 3 times/week (once weekly for additional 7 weeks MS +). 2-min short practices on all other school days |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No |

| Liehr and Diaz (2010) |

Students |

Design: RCT

w/ Health Education control Level: Student IU: 9 students |

Total #:

10 Weeks 2 Session Length: 15 minutes of MS curriculum plus 20 minutes of time to "shift from previous activities and document presence." |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No | ||

| Attention Academy Program (AAP) |

CC- No LM - No |

Napoli et al. (2005) | Students |

Design:

RCT Level: Student IU: 114 students (across 9 classrooms) |

Total #

12 Weeks: 24 Session Length: 45 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures.

Student attendance in both experimental and control conditions. |

Not Reported | Yes. Program completer had to attend 12 sessions. Control participants had to attend 12 control sessions. |

Dosage/Completers. Thirty-four

students (approx. 15%) missed more than one training/control group session and were excluded from analysis. A total of 194 students completed the program (94 experimental and 97 control). |

No |

| Standardized Meditation Program |

CC- No LM - No |

Anderson et al. (1999) |

Teachers |

Design: RCT,

with follow-up (4-weeks post) Level: Teacher IU 45 teachers |

Total #: 6 (5

weekly and 1 follow-up) plus 40-minutes a day of mediation practice. Weeks: 5 weeks Session Length: 1.5 hours for weekly sessions, 2, 20-minute daily mediations, and 1 hour for follow-up session |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures.

Participant teachers completed a questionnaire during each of the 6 sessions that asked them to estimate how many times they had meditated during the week. |

Not Reported | No | Dosage. 60% of

participating teachers reported meditating at least 6 times/wk and 40% reported 2–5 times/week |

No |

| Mindfulness Workbook (Seymour N.B. Mack's Top Secret Detective Manual) |

CC- No LM - No |

Reid & Miller (2009) | Students (with teacher delivering workbook - called "inspector connectors") |

Design:

Single group, pre-post Level: Academic Summer program IU 24 students and 4 teachers (leading 2 groups of 12 kids each) |

Total #:Varies

(24–30 sessions recommended) Weeks 6 Session Length: Not reported (and may vary based on teacher leeway to use workbook as deem appropriate) |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No |

| Transcendental Meditation (TM) |

CC-

No LM - No |

Nidich et. al. (1986) | Unclear |

Design:

Single group, pre-post Level: Student IU: 75 students (37 incoming students and 38 continuing students) |

Total #:

Unclear Weeks: Unclear Session Length: a few minutes in morning and few minutes in afternoon |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No |

| Gelderloos et al. (1987) |

Unclear |

Design: QED,

single time point design with Montessori school as comparison Level: School IU 1 School (48 students) |

Total #

Unclear Weeks Unclear Session Length: a few minutes in morning and few minutes in afternoon |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No | ||

| CC- No LM - No |

Rosaen &

Benn (2006) |

Students |

Design:

Single group, qualitative assessment Level Student IU: 10 students |

Total #:

Unclear - every school day for 12 months Weeks: approx. 52 Session Length: 10 minutes (twice a day each school day) |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No | |

| Transcendental Meditation (TM) |

CC- No LM - No |

Barnes et al. (2001) | Students |

Design: RCT,

with active, HE control condition Level: student IU: 15 students |

Total #:

approx. 40 in- school sessions plus approx. 72 at-home sessions Weeks approx. 8 Session Length: 15 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures. Attendance

at school sessions for both experimental and control group. Self-reported compliance with TM home practice. Unclear number of items or how asked. |

Not Reported | No | Dosage. Average attendance of the

TM group was 67.8% while average attendance for control group was 68.2%. Percentage of students attending at least 60% of sessions was 80% for TM group and 58% for control group. Average self-reported compliance with TM practice at home was 76.6% |

No |

| Elder et al. (2011) | Students |

Design: QED,

pre- post Level: Student IU: 68 students |

Total # Not

specified Weeks: approximately 16 Session Length: Varies - An hour for the initial set of sessions and then personal practice 10–15 minutes morning and afternoon every school day |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No | ||

| Breathing Awareness Mediation (BAM) |

CC-

No LM - No |

Gregoski et al. (2011) | Students |

Design: RCT,

with active LST (Life Skills Training) and HE (Health Education) Control conditions Level: School (to treatment group & Classroom (one teacher per semester randomly assigned to teach intervention. IU: 53 students |

Total #: 108

(Weekly health class plus home practice each weekday and twice daily on weekends). Weeks: approx. 12 Session Length: 10 minutes each |

Not Reported |

Measures.

Instructor thoroughness and enthusiasm assessed weekly by single rater using Likert scale ratings (0–4 scale). 1 item for thoroughness and 1 item for enthusiasm. Also rated Control and LST instructors on these. (fairly certain enthusiasm is for instructor - small possibility it could be about students - not fully clear from write -up) |

Measures. Attendance

& Self-reported compliance of home practice. Also measured Control and LST conditions on attendance |

Measures. Class

attentiveness assessed weekly by single rater using Likert scale ratings (0–4 scale). 1 item for attentiveness. Also rated Control and LST instructors on this. |

No | Dosage. For BAM group - Average

in-school attendance was 79% of total sessions. For all conditions - statistical differences observed for attendance between two schools (77% vs. 90%, p=.01). These differences were primarily due to bomb threats and fire alarm activations. Attendance was not statistically different by treatment group (p=.52) and the group by school interaction was non-significant (p=.46) Self-reported home compliance for home practice was 86.6% +/− 7.4% Quality & Responsiveness. All instructors were rated as competent in implementing the various components throughout the intervention: average of ratings (on scale of 0–4) were 3.34 +/− 0.26 for thoroughness; 3.28 +/− 0.32 for class attentiveness; & 3.31 +/− 0.27 for enthusiasm. No sign. differences between treatment groups, schools, teachers, or interactions of these factors observed for any components (all p's > .05) |

No |

| Barnes et al. (2008) | Students |

Design:

RCT Level: School IU: 20 students in 1 high school |

Total #:

Unclear Weeks: approx. 12 Session Length: 10 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Measures. Attendance | Not Reported | No | Dosage. Self-reported home

compliance for home practice was 86.6% +/− 7.4% Examined sodium handling excluding subjects with less than 70% attendance and adjusting for baseline values of attendance (BAM, n=11; Control, n=28), overnight urinary sodium excretion rate decreased from pre-to post-intervention in the BAM group but increased in the control group (−1.6+/− 1.1 vs 1.5+/− 0.7 mEq/hr, p < .03) as did overnight urine sodium content (−1.1+/− 0.7 vs 8+/− 0.4g, p < .03). |

Yes | ||

| Barnes et al. (2004) | Students |

Design: RCT

with active, HE control Level: Classroom IU: 34 students in 2 classrooms in same school |

Total #

approx. 60 in- school sessions and 84 at-home practice sessions; 12 instructor sessions Weeks approx. 12 Session Length: 10- minutes for practice time in-school and home; 20-minutes/week with instructor discussing |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures. Teacher/instructor recorded daily attendance of students at sessions and individual meditation practice at home. Attendance and home practice (which was 20- minute daily walks) also collected for control group. |

Not Reported | No | Dosage. The average attendance of

the meditation group was 88.5% and the control group 86%. The average self-reported compliance with meditation practice at home was 86%. |

No | ||

| Meditation Practice (no formal name) |

CC- No LM - No |

Linden (1973) | Students |

Design: RCT

with two control conditions (guidance group and no interv) Level: student IU 30 students in 1 elementary school |

Total #: 36

(twice a week) Weeks: 18 Session Length 20–25 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures.

Clinical observations as qualitative evidence that the independent variable "took." |

No | Responsiveness. Descriptive

Statement: "Many of the Subjects were unaccepting of the instructions at first or seemed to fear being judged "silly" if they accepted them…gradually the groups' nomr shifted from curiosity and hesitancy to approval and anticipation of the instructions. As the sessions continued, the subjects seemed to do the exercises more readily. It is likely that in addition to the experimenter's demand, the subjects sensed that their neighbors really were engaged in something they wished to continue doing undisturbed. Had the new group norm not become operative, the effectiveness of the mediation practice would have been nil or severely limited." |

No |

| Youth Empowerment Seminar (YES!) |

CC- No LM - No |

Ghahremani et al (2013) |

Students |

Design: QED,

pre- post Level: Classroom IU: 327 students in 3 schools (# classrooms not reported) |

Total # 20

lessons Weeks: 4 Session Length: 60 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No |

| Tai

Chi curriculum, augmented by MBSR |

CC- No LM - No |

Wall (2005) | Students |

Design

Single group, qualitative Level Student IU 14 students |

Total #: 5

(once per week) Weeks: 5 Session Length: 60 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No |

| Mindfulness- Based Youth Suicide Prevention Intervention in a Native American Community |

CC- No LM - No |

Le & Gobert (2013) | Students |

Design

Single group, pre-post Level: Student IU: 8 students |

Total #: 36

sessions Weeks: 9 Session Length: 55 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures.

Facilitators reported weekly (via open- ended personal reflection) on what group dynamic was and what contributed to the dynamics, what activities worked and why, what experiences, events or participants stood out, what helped me to be effective and to connect with youth. |

No | No | No |

| Mindfulness- based Intervention for Chronically Ill Youth |

CC- No LM - No |

Lagor et al. (2013) | Students |

Design:

Single group, pre-post Level: 1 school IU: 15 students (entire student population) |

Total #

6 Weeks 6 Session Length: 50 minutes |

Measures. Clinical

notes and records kept |

Not Reported |

Measures.

Attendance records kept at sessions. Outside practice assessed via semi-structured interviews with participants after intervention. |

Qualitatively mentioned

in discussion section. Unclear source of data. |

Yes. Treatment completers were defined as those who attended at least 4 of 6 (66%) of clinical sessions. Analyses were only conducted on treatment completers. |

Dosage/Completers. 13 out of 15

participants were "Treatment completers" - those defined as attending at least 4 of 6 sessions. Average attendance rate was 85%. Adherence/Adaptation. First clinical session delayed by 1 week. Slight adjustments made to session content based on 50- minute sessions (as opposed to curriculum which outlined 60 min sessions), Adaptations: To maximize continuity between sessions and catch up students who missed, each session began with a review of the previous sessions material. |

No |

| Yoga

Ed (modified version) |

CC- No LM - No |

Khalsa et al. (2012) | Students |

Design:

RCT Level: Class IU: 4 classes (74 students total) |

Total #:

ranged from 23– 32 sessions Weeks: 11 Session Length: 30–40 minutes long, |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures.

Participant attendance at sessions. |

Not Reported | No | Dosage. Reported the number of

participants attending at least 1 yoga session (73 out of 74 participants); average number of sessions attended for all participants (M=20.5 ;SD=7.7) as well as for those with approx. 2 sessions per week (M=18.0; SD=5.1) and those with approx. 3 sessions per week (M=23.7 (SD=9.2); & percentage of available sessions attended (80% at the beginning of the yoga program and declined to just under 70% by the end). Adaptation. Reported the number of sessions cancelled due to school events - 6 different days. |

Yes |

| Yoga Ed | CC- No LM - No |

Steiner et al. (2013) | Students |

Design

Single group, pre-post Level Student IU: 37 Students |

Total #:

approx. 28 Weeks: approx. 14 Session Length: 60 minutes |

Measures.

Instructor-report of time spent on each of the 4 main components of curriculum at each session. |

Not Reported |

Measures.

Session attendance forms in which instructors tracked participant attendance (including excuses for absences) |

Measures.

Instructor-reported "group dynamics" and individual participant engagement for each of the 4 curricular components using categories:"engagement," "medium engagement," or "need for redirection." |

No | Dosage. On average, students

attendended 90% of

sessions. Responsiveness. Students were engaged for the majority (78%) of poses. Adherence. "Fidelity was ensured because of experienced yoga instructors following Yoga Ed curriculum, as well as instructor-rated adherence." No supporting data or methods to back up statement. |

No |

| Kripalu-based Yoga Program |

CC-

Yes LM - No |

Noggle et al. (2012) | Students |

Design: RCT,

active control (PE as usual) Level: Student IU: 36 students within 3 PE classes |

Total #: 28

sessions Weeks 10 weeks Session Length: 30–40 minutes |

Not

Reported (assert assessed adherence, but does not fit this definition) |

Not Reported |

Measures.

Participant attendance at sessions. Yoga Evaluation Questionnaire (YEQ) asked if students used yoga skills at school or home on a 10-cm. visual analgue scale on which mark degree of agreement from "not at all" to "very much so". Not sure how many items. |

Not Reported | No | Dosage. Central tendencies of

attendance rates for experimental condition (Mean =58%; =/- 26% SD; Median = 64%, and Mode = 75%). Range of attendance (0% - 93%). Attendance less than 25% of sessions for 7 of 36 students. Qualitatively report range of answers for outside use. Specifically, when asked whether yoga was helpful or whether they used any yoga skills at school and home, responses were scattered more evenly across scale (data not shown) indicating perhaps not all students who liked yoga were applying it outside of class. Examined correlation between attendance rates and all outcome measures and NONE were correlated |

Yes |

| Conboy et al. (2013) | Students |

Design: RCT,

active control (PE as usual) Level: Student IU: approx. 56 - because say selected half to include in this study |

Total #: 32

sessions Weeks 12 weeks Session Length: 30 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | No | No | No | ||

| Get Ready to Learn (GRTL) |

CC- No LM - No |

Koenig et al. (2012) | Students |

Design QED,

pre- post Level: Classroom IU: 4 classrooms (24 students) |

Total # 80

sessions Weeks: 16 Session Length: 15–20 minutes |

Measures. FOI

assessed using checklist and videotaped sessions. Checklist included 16- pt. scale in five categories: 1) classroom-environment, 2) classroom organization and setup, 3) program implementation by the teacher, 4) DVD routine and student support, and 5) GRTL program conclusion. A score of 12–16 points indicates good program implementation. Researchers used checklists and video tapes to reach 80% agreement on categories. Once reliable, observed classrooms directly in 4 intervention classrooms (unclear how many times). |

Unclear. The categories outlined as part of overall FOI could be conceptualized as "quality" but don't talk about it as such. |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Yes. A score of 12–16 points on FOI checklist indicated "good program implementation." |

Overall Fidelity/Adherence.

Classroom observations were rated for fidelity, and all classes scored within the "good" implementation range. Unclear which dimensions used to construct Overall Fidelity. Reliability. Raters achieved 100% agreement on two independent samples. |

No |

| Yoga Fitness for Kids (Gaiam, 2003) |

CC- No LM - No |

Peck et al. (2005) | Students |

Design:

QED, multiple baseline, intervention, and follow-up periods with convenience comparison group Level: Grade-level IU: 10 students (3 in Grade 1, 3 in Grade 2, and 3 in Grade 3) |

Total #: 6 (2

X per week) Weeks 3 Session Length: 30 minutes |

Measures. Treatment

Integrity Checklist completed by data collector. Intervention components checked off if completed as intended. These included 2 adherence items: 1) all participants dressed appropriately, and 2) researcher played yoga videotape and participants followed along with deep breaths, physical postures, and relaxation exercises. |

Not Reported |

Measures. Attendance

for group recorded via Treatment Integrity Checklist completed by data collector. Single Item: all participants in grade level group were present at session. |

Not Reported | No | Dosage/Adherence. It was

determined that all elements of the intervention were implemented with 100% accuracy. This is what is termed "Treatment Integrity" which is composed of the 3 items (2 adherence and 1 dosage) but, don't say how determined or calculated this. |

No |

| Yoga Program | CC- No LM - No |

Hagins, Haden, Daly (2013) |

Students |

Design: RCT,

with PE control Level Student IU: 15 students |

Total #:

approx. 30-45 (says 3 X per week in one place and 2 X per week in another) Weeks: 15 Session Length 50 minutes |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures.

Student attendance at each session. Assessed in both Yoga and PE Control groups. |

Measures.

"Child Engagement Index" created in which Yoga & PE instructors completed index on each child twice within the trial period (approx. 5 weeks and 10 weeks). 3-point scale anchored by the terms "minimal", "moderate", and "maximum" engagement - narrative text describing each. Put form online via hyperlink as supplemental material for readers. |

No | Dosage. Mean attendance for yoga

group was 26.87 classes (SD=4.85); Mean attendance for PE group was 22.8 classes (SD=7.36). Responsiveness. Yoga Group: At Time 1 (5 weeks in) 10 students were maximally engaged, 4 were moderately engaged, and 0 were minimally engaged. At Time 2 (10 weeks in), 8 students maximally engaged, 5 students moderately engaged, and 0 minimally engaged. PE Group At Time 1 (5 weeks in) 6 students were maximally engaged, 8 were moderately engaged, and 0 were minimally engaged. At Time 2 (10 weeks in), 8 students maximally engaged, 5 students moderately engaged, and 0 minimally engaged. No sig differences in engagement between groups. |

No |

| Bent on Learning |

CC- No LM - No |

Berger et al. (2009) | Students |

Design: QED,

pre- post Level: After-school program IU: 39 students in 1 after-school program. |

Total #: 12 (1

per week) Weeks: 12 Session Length 1 hour |

Not Reported | Not Reported |

Measures. Attendance

for each student (yoga group only). Recorded by after- school program teachers. Also recorded if child unable to participate due to injury or if the yoga teacher was absent. Collected for 10 of the 12 classes. |

Not Reported | No | Dosage. Children attended

68.5% (SD=21.6) of yoga classes. This is an estimate as data were obtained for only 10 of 12 classes. |

No |

| Mindful Awareness for Girls through Yoga |

CC- No LM - No |

White (2012) | Students |

Design:

RCT Level School IU: 1 School (190 students) |

Total # 8

sessions (plus 60 minutes of homework practice/week) Weeks: 8 Session Length: 60 minutes weekly session + 10 min of HW 6 days/week |

Unclear if

Assessed Measures. Study fidelity maintained through Intervention manual 2) journal kept by interventionist c) an intervention checklist monitored by research assistants, d) written instructions, and e) homework with pictures and audio instructions, and f) feedback during sessions |

Not Reported |

Measures. 1)

Participant attendance at sessions and 2) Self-reported home practice of yoga. However, measures not described so don't know number of items or quant/qual. |

Not Reported | No | Dosage. 1) Session attendance

reported as a range (ranged between 3–8 sessions) and percent of participants completing all eight sessions (61.4%) & 2) Amount of home practice (which is defined as part of "dosage": Average frequency (10.8 times; SD=+/− 9.6). Ranged from 0–42 times Amount of home practice (which is defined as part of "dosage": Average frequency (10.8 times; SD=+/− 9.6). Ranged from 0–42 times Examined correlation between both participant dosage variables and all outcome variables. 1 was significant. That is, there was a positive correlation between home yoga practice and perceived stress (r=.29, p< .05) |

Yes |

Program and study characteristics

The 48 studies included here evaluated the impact of 35 different mindfulness and yoga programs implemented in school settings. Of these 35 programs, 22 (63%) were primarily meditation-based; many of these were adapted from the standard MBSR program (Kabat-Zinn 1990). Eight programs (23%) were primarily yoga-based, focusing on physical postures (asanas), deep breathing, relaxation, and some meditation. The remaining 5 programs (14%) focused equally on meditation and yoga practices. Twenty-four programs (69%) targeted students, 8 programs (23%) targeted teachers, and 3 programs (8%) targeted both students and teachers.

The manner in which these programs were structured and delivered varied across the 48 studies. Specifically, the total number of sessions delivered ranged from 5 to 180 and the length of sessions ranged from “a few minutes” to weekend-long retreats. The most common session length was between 30 to 60 minutes (approximately one class-period). The intensity of program delivery varied from program components being delivered every school day to every couple of weeks. The shortest program duration (from start to end of program delivery) was 2 weeks while the longest duration was 12-months. Finally, programs utilized various session formats including individual sessions, group meetings and/or lessons, individual coaching calls, full-day long sessions, and weekend residential retreats.

Nineteen studies (40%) evaluated programs implemented in elementary schools, 8% in middle schools, 31% in high schools, and 10% across multiple K-12 school settings. Five studies (10%) did not report the grade levels in which programs were implemented. Thirty-five studies (73%) implemented programs during school hours, either integrated into classroom activities, during health class, physical education, a resource period, or briefly at the start or end of the school day. Eleven studies (23%), most of which targeted teachers, implemented programs outside school hours, either directly after school, in the evenings, or on weekends. Two studies (4%)--both programs targeting students and teachers--implemented the student component during school hours and the teacher component outside school hours. Four of the studies (8%) implemented programs either during summer camp within a school setting or during summer teacher professional development.

In addition to program and implementation differences, there was variation in study designs and sample sizes. Of the 48 studies included, 26 (54%) were experimental designs or randomized control trials (RCTS), 13 (27%) were quasi-experimental (QEDS) and 10 (21%) were single-group designs (the total number of study designs equals 49 because one article (Jennings et al. 2011) included a larger study comprised of two sub-studies). Sample sizes ranged from 8 to 409. Three-fourths (or 75%) of studies had a total sample size of less than 100. Most studies were implemented in 1 or 2 schools or a few classrooms, although several studies implemented a program in more than 15 classrooms (Black & Fernando 2013; Lantieri et al. 2011), suggesting variation in scope of program implementation.

Specification of program core components and their association with relevant outcomes

Most often, potential program core components were not clearly articulated in studies. Almost all of the studies provided a general description of program content by summarizing the major lesson themes or content in the order taught, the instructional or pedagogical techniques used to engage participants in learning, the key practices taught (e.g. awareness of breathing or physical postures), and/or the overall program goals. Many programs were described as being “adapted” from more established interventions such as MBSR (Kabat-Zinn 1990), Semple’s work (Semple et al. 2005), or Mind-Body Awareness which combines aspects of MBSR and Social Emotional Learning (SEL). For these adapted programs, many studies described the program in terms of how they differed or were adapted from the original program. Only a handful of studies identified program components in terms of being “key,” “core,” or “essential.” There were no studies that formally distinguished potential structural core components from process core components.

While the majority of studies outlined a general theory of anticipated programmatic impacts based on the effects of mindfulness or yoga programs more broadly, only 3 (6%) published or referenced a logic model or theory of change (Jennings et al. 2013; Mendelson et al. 2010; Roeser et al. 2013). In addition, only a handful of studies included more specified programmatic theory – that is, theory specifying the rationale for inclusion of specific program components and how those components were intended to produce specific outcomes or contribute to participant engagement. Not surprisingly, these were also the studies that distinguished program components in terms of being “key” or “core.” These programs and studies included: Learning to BREATHE ((Metz et al, 2013), Mindfulness Education (ME) Program (Schonert-Reichl & Lawlor 2010), Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education (CARE) (Jennings et. al. 2013), Moving into Learning (MIL) (Klatt et al. 2013), SMART-in-Education Program (Roeser et al. 2013), and a Kripalu-based Yoga Program (Noggle et al. 2012).

The Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education (CARE) program (Jennings et al. 2010; Jennings et al. 2013) and the SMART-in-Education Program (Roeser et al. 2013) are noteworthy with respect to articulating program components and theoretical underpinnings. Jennings and her colleagues (2013) outlined a CARE intervention logic model that specifies the main program components and the proximal and long-term outcomes hypothesized to result from program implementation. Each of the three main components - Emotion Skills Instruction, Mindfulness Practices, and Compassion Practices – was described in terms of the rationale and empirical evidence behind its inclusion, the approximate percentage of the program devoted to it, as well as the specific kinds of activities delivered as part of each. Roeser and his colleagues outline very specific programmatic theory in terms of how mindful self-regulation skills and self-compassionate mind-sets for coping are hypothesized to impact specific mechanisms underlying regulation. They also outline the main program components in terms of teaching/pedagogical techniques and specific practices to facilitate experiential learning. In addition, their programmatic logic model includes program fidelity as an important facilitator of producing hypothesized program effects.

FOI rigor and reporting

Based on our criteria and coding, the majority of studies - 30 out of 48 or 63% of the studies reviewed -assessed at least one dimension of FOI. Nine studies (just under 20%) assessed 2 or 3 dimension of FOI. No study we reviewed assessed all 4 dimensions of FOI. Eighteen studies (37%) did not assess any aspect of FOI. Table 1 provides a summary of the number and percent of studies that assessed and reported FOI data in a rigorous manner.

Table 1.

Number and Percent of Reviewed Studies Collecting and Reporting FOI Data in Rigorous Manner for FOI Dimensions

| FOI

Dimension Sub-Dimension |

Studies Measuring |

Studies

Using Observational Measures |

Studies Where >1 Source Used |

Studies Assessing Reliability or Validity |

Studies Establishing A-Priori Cut-offs |

Studies Monitoring Comparison Condition |

Studies Reporting Adaptations |

Studies Reporting Level of FOI |

Studies Linking Aspect(s) of FOI to Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program Adherence |

9 (19%) | 7 (15%) | 3 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (6%) | 8 (17%) | 0 (0%) |

| Program Quality |

5 (10%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Participant Dosage |

23 (48%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (6%) | 5 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 22 (46%) | 6 (13%) |

| Session Attendance |

16 (33%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (6%) | 5 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (31%) | 3 (6%) |

| Outside Practice |

16 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (31%) | 3 (6%) |

| Participant Responsiveness |

7 (15%) | 3 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

The most commonly assessed dimension of FOI was participant dosage. Dosage was evaluated in two ways: participant attendance at program sessions and participant outside practice (i.e., the frequency of mindfulness practice at home or outside of formal program time). Almost half the studies (23 of 48) assessed one or both of these aspects of participant dosage. Fewer than 20% of studies assessed program adherence, program quality, or participant responsiveness (see Table 1 for greater detail).

Rigorous FOI assessment is also characterized by at least two rating sources for a single dimension, observational measures, testing of reliability and validity, a priori cut-offs for program delivery “as intended,” monitoring of control/comparison conditions, and reporting any adaptations made during program delivery. Nine studies (19%) used some kind of observational measure to assess an aspect of FOI, although only two studies (Koenig et al. 2012 & Peck et al. 2005) reported the number of items comprising an observational measure and/or how often observations were conducted. Five studies (10%) used more than one source of data to assess a single dimension of FOI, using both a self-report checklist for the intervention facilitator and an observational assessment, generally of program adherence. None evaluated the convergent validity of these measures. One study assessed the reliability of an observational measure across two independent coders (Koenig et al. 2012).

Four studies (8%) established cut-offs for some aspect of FOI. Three of the four studies defined “program completers” based on the number of sessions attended, specifying that participants must attend at least 66%, 73%, or 100% of sessions in order to qualify as a “program completer.” The other study (Koenig et al. 2012) established an a priori cut off for what “good” implementation would entail. This study used 5 categories to construct a 16-point scale on which a score of 12–16 indicates “good” implementation. Five studies (13% of studies including a control/comparison condition) assessed an aspect of FOI in both experimental and control conditions (Barnes et al. 2001; Barnes et al. 2004; Gregogski et al. 2011; Hagins et al. 2013; & Napoli et al. 2005). All five experimental studies assessed dosage, namely attendance, in both experimental and active control conditions. Two of the studies assessed participant responsiveness and one study instructor quality in both experimental and control conditions. Three studies (6%) reported adaptations made to program delivery (Jennings et al. 2011; Khalsa et al. 2012, Lagor et al. 2013). Program adaptations included modifying curriculum delivery to fit a 50-minute format rather than the originally designed 60-minute format, cancelling a number of sessions due to school events, and cancelling a training session due to a heavy snow storm and condensing that material into one of the final sessions.

The most common way to report participant dosage data was the average percent of lessons attended by participants or the percent of participants attending a certain proportion of lessons (e.g. over 75% or all lessons offered). Across studies these average attendance rates varied and variation was typically reported as a range or standard deviation around the mean. For outside practice most studies reported the average number of days per week or average number of minutes per day participants engaged in practice outside of class or at home. Several studies reported “compliance” meaning the percent of participants reporting that they complied with suggested guidelines for outside practice.

Adherence was generally reported quantitatively as an average and/or range of lessons or percent of lesson components implemented by instructors. The vast majority of studies that assessed adherence in this manner reported “moderate” to “high” fidelity – with “moderate” the label for 70–80% of lessons/content and “high” as being over 80% adherence. Numerous studies reported instructors implemented a program with “high fidelity” without any numerical quantification or qualification, including several studies that stated a program was implemented with “high” or 100% fidelity because the program was implemented by the program developers.