Abstract

Muscle strength declines with age in part due to a decline of Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium stores. Skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptors (Cav1.1) initiate muscle contraction by activating ryanodine receptors in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Cav1.1 channel activity is enhanced by a retrograde stimulatory signal delivered by the ryanodine receptor. JP45 is a membrane protein interacting with Cav1.1 and the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ storage protein calsequestrin (CASQ1). Here we show that JP45 and CASQ1 strengthen skeletal muscle contraction by modulating Cav1.1 channel activity. Using muscle fibres from JP45 and CASQ1 double knockout mice, we demonstrate that Ca2+ transients evoked by tetanic stimulation are the result of massive Ca2+ influx due to enhanced Cav1.1 channel activity, which restores muscle strength in JP45/CASQ1 double knockout mice. We envision that JP45 and CASQ1 may be candidate targets for the development of new therapeutic strategies against decay of skeletal muscle strength caused by a decrease in sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content.

Activation of skeletal muscle contraction is initiated by the propagation of the action potential deep into the muscle fibre by means of the transverse tubular system (T system)1–3. T-tubule depolarization causes massive release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) throughout the entire length of the muscle fibre by a process called excitation-contraction coupling1,2. Loss of muscle function has been recognized as a debilitating and life-threatening condition not only in the elderly, but also in cachexia in cancer patients and in all those clinical conditions associated with prolonged bed rest4,5. The decay of muscle strength is caused by several factors, including a decrease of releasable calcium from the skeletal muscle SR calcium store6,7.

EC coupling is operated by a macromolecular complex comprising the α1-subunit of the voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channel (dihydropyridine receptor, DHPR, Cav1.1), the ryanodine receptor (RyR) and calsequestrin (CASQ1)8, in the contact region between the T system and the SR membrane3. Cav1.1 acts as a voltage sensor and generates orthograde signals that cause opening of the RyR whereby Ca2+ is released from the SR into the myoplasm, leading to activation of the contractile proteins1. Analysis of voltage-dependent calcium currents in RyR1 knockout (KO) muscle cells was fundamental to clarify the signalling mechanisms between the RyR and Cav1.1. It is now accepted that the RyR1 not only receives an orthograde signal from Cav1.1, but also generates a retrograde signal which is important for the activation of Cav1.1 channel activity9,10. The mechanism by which the retrograde Ca2+ current enhancement is modulated and its exact physiological role remain elusive. Although calcium influx across the sarcolemma is thought to be non relevant for muscle contraction11, it has been proposed that it may have a role in replenishing the SR during sustained muscle contractions12. Two different modes of calcium influx in skeletal muscle have been described: (i) calcium influx via Cav1.1 associated with prolonged membrane depolarization is referred to as excitation-coupled calcium entry (ECCE)10, (ii) calcium influx via STIM1 and OraI1 stimulated by internal store depletion is referred to as store-operated calcium entry (SOCE)13–15. However, the analysis of macroscopic calcium currents in adult muscle fibres recorded under voltage clamp condition16 suggests that both voltage-dependent calcium release and/or SR calcium depletion are not sufficient to activate inward calcium currents and thus challenged the physiological relevance of ECCE and SOCE in adult mammalian fibres. Nevertheless, calcium influx in muscle cells deserves further investigation, because of the potential impact of calcium influx in determining releasable SR calcium content17, a crucial factor for proper sustained muscle force development 6,7,18.

Calcium influx in skeletal muscle is affected by drugs19,20 and by accessory proteins such as junctophyllin and mitsugumin-29, two proteins localized in the membrane compartment which form the junction between T tubules and SR12,21. T tubules-SR junction membranes encompasses also JP45, a developmentally regulated 45-kDa transmembrane protein that interacts via its luminal carboxy-terminal domain with CASQ1, the major calcium storage protein of SR, and with its amino terminal domain with Cav1.122. Ablation of calsequestrin 1 in skeletal muscle fibres results in a decrease of total calcium release from the SR, which leads to impaired muscle performance and contractile activation23–26. Chronic depletion of JP45 induces a decrease of muscle strength in 3-month-old JP45 KO mice27. The decay in strength is apparently not linked to atrophy, but to defects in the EC-coupling machinery caused by alteration of the functional expression of DHPR Cav1.1 in the T-tubular network.

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that the skeletal muscle Cav1.1 channel activity is not only regulated by the RyR, but additionally by the JP45/CASQ1 complex. We generated double JP45 and CASQ1 KO (DKO) and compared their Cav1.1-mediated Ca2+ signals to those observed in WT and each single JP45 and CASQ1 KO mice. Our results show that in DKO mice, tetanic stimulation of skeletal muscle fibres causes massive Ca2+ influx due to enhanced Cav1.1 channel activity and this Ca2+ influx restores muscle strength. By using this animal model, we have unveiled a signalling pathway which may be an important target for drugs against the loss of skeletal muscle strength caused by decrease of the SR calcium content.

Results

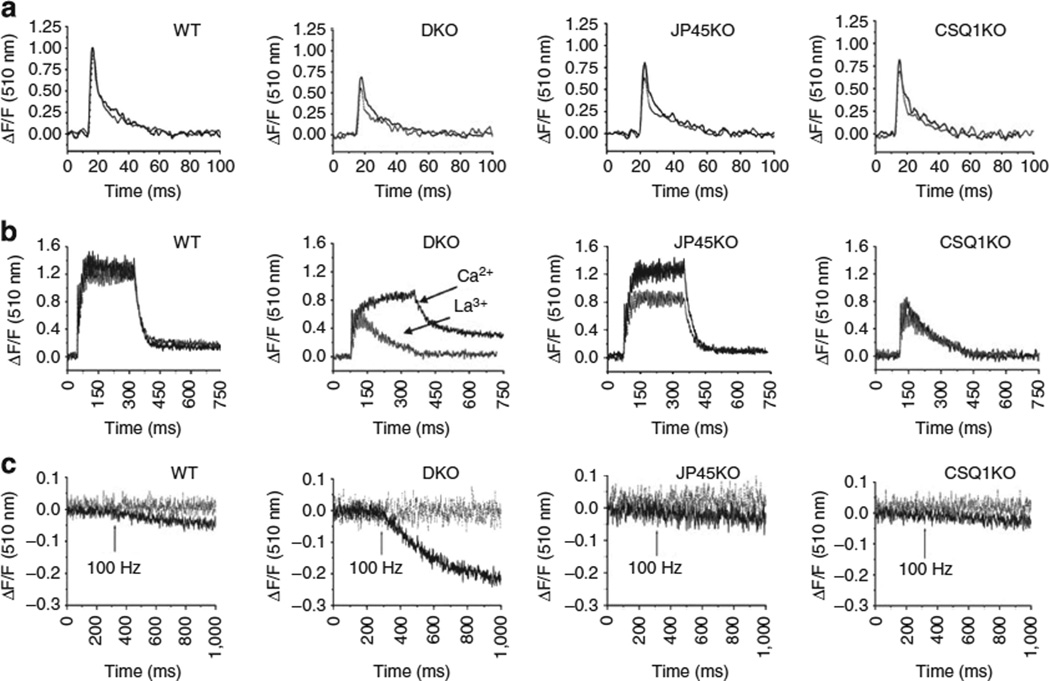

Calcium transient in flexor digitorum brevis fibres

We compared Ca2+ homoeostasis in WT, single JP45 and CSQ1 KO and DKO using the ratiometric Ca2+ indicator Indo-1 and found that the resting calcium concentration was increased in DKO 1.15 ± 0.23* (n = 48) fibres compared with WT (0.92 ± 0.10, n = 40), JP45 null (1.03±0.18, n = 42) and CASQ1 null (0.95±0.11) fibres (F405/F480 indo-1 ratio values are mean ± s.d.; *WT versus DKO P < 0.001 two tailed Mann–Whitney). In the presence of 1.8 mM Ca2+ in the extracellular solution, the peak intracellular Ca2+ transients measured with the low-affinity calcium indicator MagFluo4 were 1.009±0.18 (n = 47), 0.67±0.16 (n = 49), 0.80±0.25 (n = 40) and 0.82±0.25 (n = 47) for WT, DKO, JP45 KO and CASQ1 KO, respectively (ΔF/Fo values are expressed as mean± s.d., Fig. 1 top panels). The significant decrease of the peak Ca2+ transient in DKO fibres is not due to a lower membrane density of RyRs (Supplementary Fig. S1). The half-time of the decay of the Ca2+ transients in flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) fibres from DKO mice was significantly slower compared with WT (3.7±0.7, n = 47 and 4.8±1.9 ms, n = 49 in WT and DKO fibres, respectively. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) P-values < 0.0001; multicomparison Dun-net’s post test WT versus DKO P < 0.01).

Figure 1. Ca2+ transients and Mn2+ quenching in FDB fibres from single and DKO mice.

FDB fibres were loaded with the fast low-affinity Ca2+ dye Mag-Fluo-4AM 21,22. (a) Ca2+ transients were triggered by supramaximal field stimulation with single pulses of 0.5 ms duration. Continuous lines: Ca2+ transients recordings in an external solution containing 1.8 mM CaCl2. Overall ANOVA P-value < 0.0001; multicomparison Dunnet’s ANOVA post test shows difference between of the peak calcium values: WT versus DKO P < 0.01, WT versus JP45 KO P < 0.01; WT versus CASQ1 KO P < 0.01; dotted grey lines: Ca2+ transients recordings in an external solution containing 100 µM La3+. Overall ANOVA P-value < 0.0001; multicomparison Dunnet’s ANOVA post test shows difference between of the peak calcium values: WT versus DKO P < 0.01, WT versus JP45 KO P < 0.01, WT versus CASQ1 KO P < 0.01. (b) Recording of Ca2+ transients upon stimulation with repetitive pulses at 100 Hz for 300 ms duration. Black and grey lines show recordings in the presence of 1.8 mM Ca2+ and 100 µM La3+ in the external solution, respectively. In the presence of La3+, the overall ANOVA P-value is < 0.0001; multicomparison Dunnet’s ANOVA post test shows differences: WT versus DKO P < 0.01, WT versus JP45 KO P < 0.05, WT versus CASQ1 KO P < 0.01. (c) Mn2+ quenching of Fura-2 fluorescence. Black lines: Mn2+ influx was triggered by repetitive pulses at 100 Hz (arrow) for 300 ms duration. Overall ANOVA P-value < 0.0001; multicomparison Dunnet’s ANOVA post test shows differences: WT versus DKO P < 0.01. Dotted grey lines: Mn2+ quenching recordings in the presence of 50 µM nifedipine in the external solution.

Enhanced ECCE in FDB fibres from DKO mice

The slower decay of the calcium transients in FBD fibres from DKO mice is not due to a decrease of calcium uptake in to the SR by the Ca2+ pump because we did not observe a reduction of the SERCA1 and SERCA2 expression in DKO mice (Supplementary Fig. S1). The increase of the half-time of the decay of the calcium transient is rather linked to an influx of extracellular Ca2+, as in the presence of La3+, a non-specific calcium channel blocker10, the difference in the half-time for the decay of calcium transient between WT and DKO fibres disappears (3.1±0.7 and 3.3±1.1 ms for WT and DKO, respectively). The effect of La3+ was much more evident upon stimulation of FDB fibres with repetitive action potentials. In the presence of La3+, the Ca2+ transient amplitude of tetanic stimulation was highest in WT fibres (1.31 ± 0.28; n = 37) compared with that of DKO (0.62 ± 0.14*, n = 34), JP45 KO (1.05 ± 0.30§, n = 26) and CASQ1 (0.70 ± 0.15*n = 24) (DF/Fo values are mean ± s.d., *P < 0.01, §P < 0.05, (multicomparison Dunnet’s ANOVA post test, Fig. 1). In CASQ1 null fibres, the summation of Ca2+ transient peaks was dramatically different compared with WT, JP45 null and DKO fibres. After the few initial peaks, which display an amplitude 50% lower compared with WT, the fused Ca2+ transients in CASQ1 KO fibres rapidly decayed to basal levels. This event reflects depletion of Ca2+ stores due to the ablation of the Ca2+ storage protein23–25. However, at variance with CASQ1 null fibres, the double KO (DKO) fibres exhibit a sustained Ca2+ transient which persisted for the entire duration of the repetitive stimulation in the presence of calcium in the extracellular solution (Fig. 1 middle panels, arrow Ca2+).

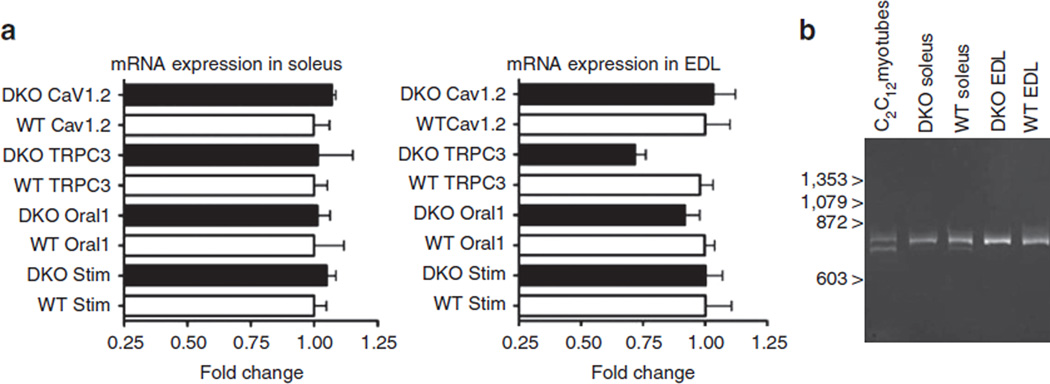

Depolarization of DKO fibres causes massive Ca2+ influx

The sustained calcium transients evoked by tetanic stimulation in DKO fibres is caused by massive Ca2+ influx, as in the presence of 100 mM La3+ in the external solution (Fig. 1 middle panel, arrow La3+), the Ca2+ transient curve overlapped with that of CASQ1 KO fibres. These data unambiguously demonstrate that ablation of JP45 in a CASQ1 null background unveils a robust Ca2+ influx component coupled to membrane depolarization. This conclusion is also supported by fura-2 manganese quenching experiments performed in FDB fibres (Fig. 1 lower panels). At an excitation wavelength of 360 nm, the Ca2+ independent isosbestic wavelength of fura-2, Mn2+ entry quenches fura-2 fluorescence28. We measured the extent of the fluorescence quenching at the end of a 300-ms-long train of pulses at 100 Hz. We found that manganese quenching of fura-2 fluorescence was − 0.11 ±0.039 (n = 16), −0.034 ±0.021 (n=17), − 0.034 ±0.011 (n = 19), −0.027 ±0.019 (n = 35) for DKO, WT, JP45 KO and CASQ1 KO fibres, respectively (ΔF/Fo values are mean ± s.d.). The threefold increase of fura-2 fluorescence quenching by Mn2+ in DKO fibres was abolished by the addition of 50 µM nifedipine (Fig. 1 lower panels grey line), a specific inhibitor of Ca 1.110. Skeletal muscle membrane encompasses several molecules that can mediate calcium influx, including the neonatal splice variant (Δ29) of Cav1.129, TRPC315 and OraI1/Stim114, Cav1.2. We investigated the expression levels of other known calcium influx channels, and we found no changes both in fast and slow DKO fibres (Fig. 2). Altogether, these data support the conclusion that the increase of excitation-coupled Mn2+ entry is mediated by an enhancement of calcium currents through adult form Cav1.110. The next set of experiments was designed to evaluate the changes in the functional properties of the Cav1.1.

Figure 2. Expression of calcium entry proteins in fast and slow muscles from DKO mice.

(a) Real-time reverse transcription (RT) PCR from soleus and EDL of wild-type and DKO mice. Real-time RT PCR was carried out as previously described41. Briefly, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent from Soleus or EDL muscles after frozen tissue homogenization, and Cav1.2, TRPC3, OraI1 and STIM1 gene expression was evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR. Boxes represent the mean (±s.e.m.) fold change compared with values obtained from WT for each gene of interest. Gene expression levels were normalized to the expression of the Tata box-binding protein (TBP) and desmin, whose expression was equal between wild-type and KO animals. Pooled data are results carried out on muscles from 5 to 7 different mice. (b) Expression of Δ29 Cav1.1 isoform mRNA in EDL and Soleus from 1-month-old WT and DKO mice. The expression of neonatal Δ29 Cav1.1 isoforms allele (lower band) is present in mRNA from C2C12 myotubes. The Δ29 Cav1.1 isoforms could be absent or below the detection limit of PCR in EDL. Soleus displays a faint band corresponding to the Δ29 exon Cav1.1 transcript.

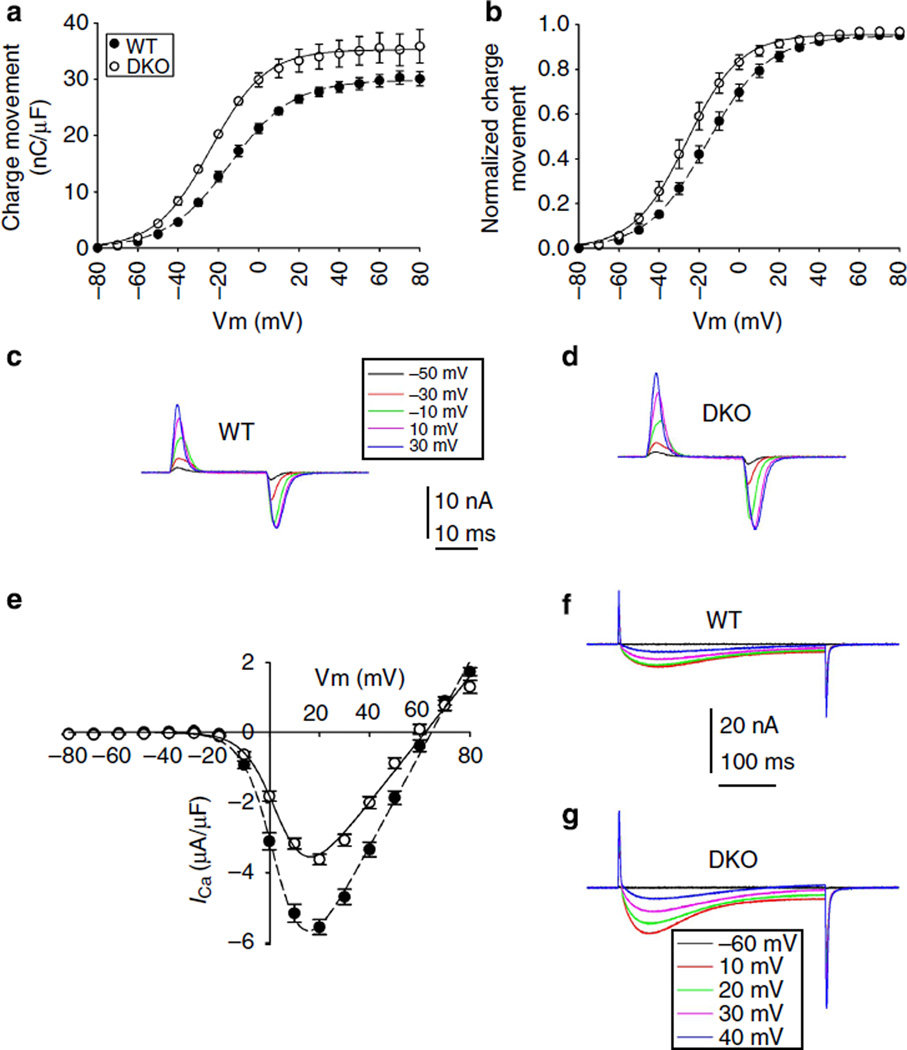

Increase of Cav1.1 channel activity in DKO fibres

The T-tubular system is the membrane compartment richest in Cav1.130 and high-resolution electron microscopy shows that volume and surface of the T-tubular system in FDB fibres from 1-month-old DKO and WT mice is not different (Supplementary Fig. S2). Thus, the threefold increase of excitation-coupled Mn2+ entry is not fully explained by changes of T-tubular membrane extensions or by a small increase of the Cav1.1 membrane density (Supplementary Fig. S1), but rather could be consistent with a modification of the channel activity of Cav1.1. To examine this possibility, we investigated the capacitive and Ca2+ currents of Cav1.1 in FDB fibres from DKO and WT mice by using the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique. Intact FDB fibres from DKO mice show 10mV shift to more negative potential of the half maximal gating charge, and small nonsignificant increase (15%) in maximal gating charge, compared with control (Fig. 3b and Table 1). The small increase of maximal gating charges do not account for the ~ 45% increase of in peak Ca2+ current density, which was found in DKO FDB fibres (Fig. 3e). Half-maximal Ca2+ currents in wild-type (WT) and DKO mice were observed at very similar membrane potentials (Table 2). These results demonstrate that enhanced calcium influx is accounted for an increase of the Cav1.1 channel activity.

Figure 3. Voltage dependence of charge movements and Ca2+ currents.

(a) Charge movement-membrane potential relationship for WT (n = 13) and DKO (n= 15) muscle fibres. Values are mean ± s.e.m. error bars show s.e.m. (b) Normalized values to maximal charge movement. Values are mean ± s.e.m. error bars show s.e.m. (c-d) Representative charge movement traces recorded in FDB fibres voltage-clamped in the whole-cell configuration of the patch clamp. Holding potential: − 80 mV. Command pulses of 25 ms duration evoked currents from − 80 to 80 mV. Selected traces correspond to the steepest part of the curve. Notice the larger amplitude and 10 mV shift of the curve toward more negative potentials in DKO compared with WT mice. (e) Calcium current-membrane voltage relationship. Command pulses of 400 ms duration evoked currents from − 80 to 80 mV. Notice the larger current amplitude for DKO (n= 19) compared with WT (n= 29) mice. Values are mean ± s.e.m. (f-g) Representative calcium currents recorded at the indicated membrane voltages. Fitting curves, their respective equations and best fitting parameter values are described in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Best-fitting parameters describing the voltage-dependence of charge movement.

| Qmax (nC µF−1) | VQ1/2 (mV) | K | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT (n = 13) | 30 ± 8 | −14 ± 2.2 | 16 ± 1.5 |

| DKO | 35 ±11 | −24±1.7 | 14 ± 1.9 |

| (n = 15) | (P = 0.724) | (P = 0.001) | (P = 0.426) |

Data points were fitted to a Boltzmann equation of the form: Qon = Qmax/[1 + exp(VQ1/2 − Vm)/K], where Qmax is the maximum charge, Vm is the membrane potential, VQ1/2 is the charge movement half-activation potential and K is the steepness of the curve as described in ref. 27. The number of FDB fibres from three to four mice is between parentheses. Results are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test. The α-level was set at P=0.05.

Table 2.

Best-fitting parameters describing the voltage-dependence of calcium current.

| Gmax (nS/nF) | V1/2 (mV) | Vr (mV) | z | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (n = 29) | 90 ± 8 | 4.7 ± 2.5 | 62 ±3.1 | 3.9 ± 0.6 |

| DKO | 132 ± 12 | 3.8 ± 1.9 | 64 ±4.4 | 4.0 ± 0.8 |

| (n = 29) | (P = 0.005) | (P = 0.775) | (P = 0.712) | (P = 0.921) |

Data points were fitted to the following equation: ICa = Gmax (V − Vm)/{1 + exp[zF(V1/2 − V)/RT]}, where Gmax is the maximum conductance, V is the membrane potential, Vr is the reversal potential, V1/2 is the half-activation potential, z is the effective valence, F is the Faraday constant, R is the gas constant and T is the absolute temperature (296 K) as described in ref. 43. The number of FDB fibres from three to four mice is between parentheses. Results are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test. The α-level was set at P= 0.05.

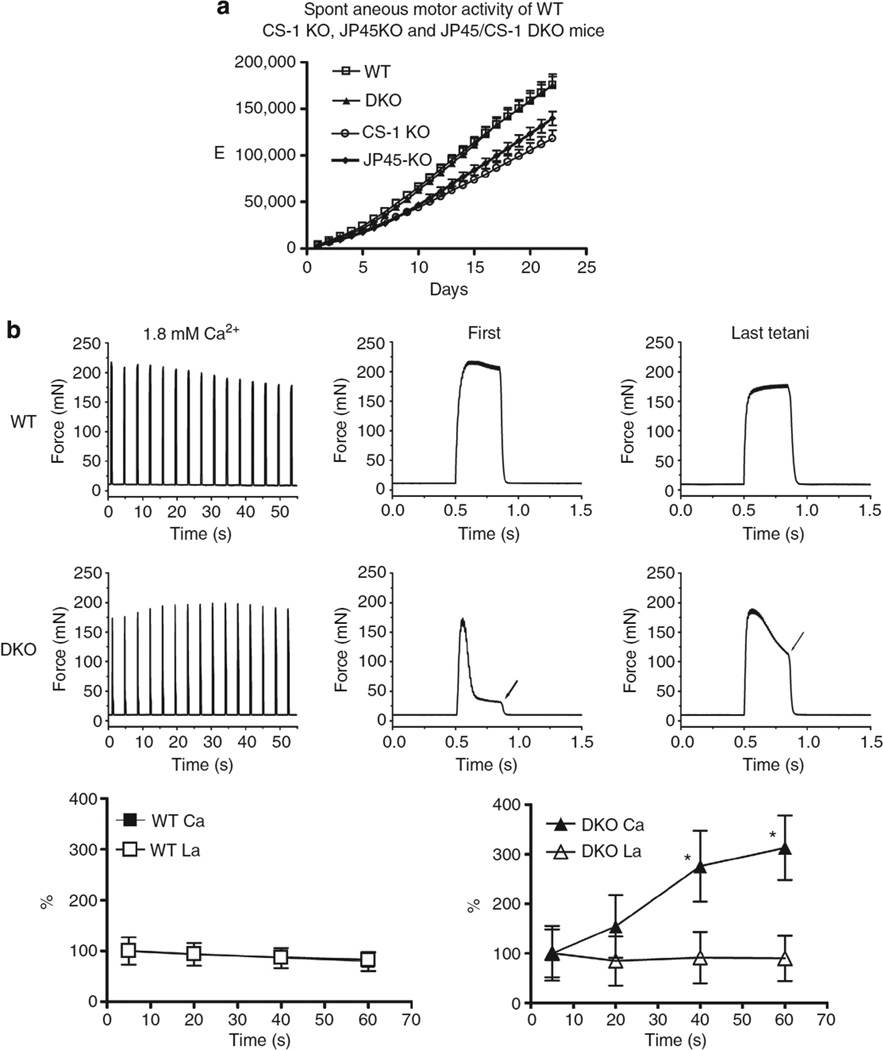

Skeletal muscle performance is restored in DKO mice

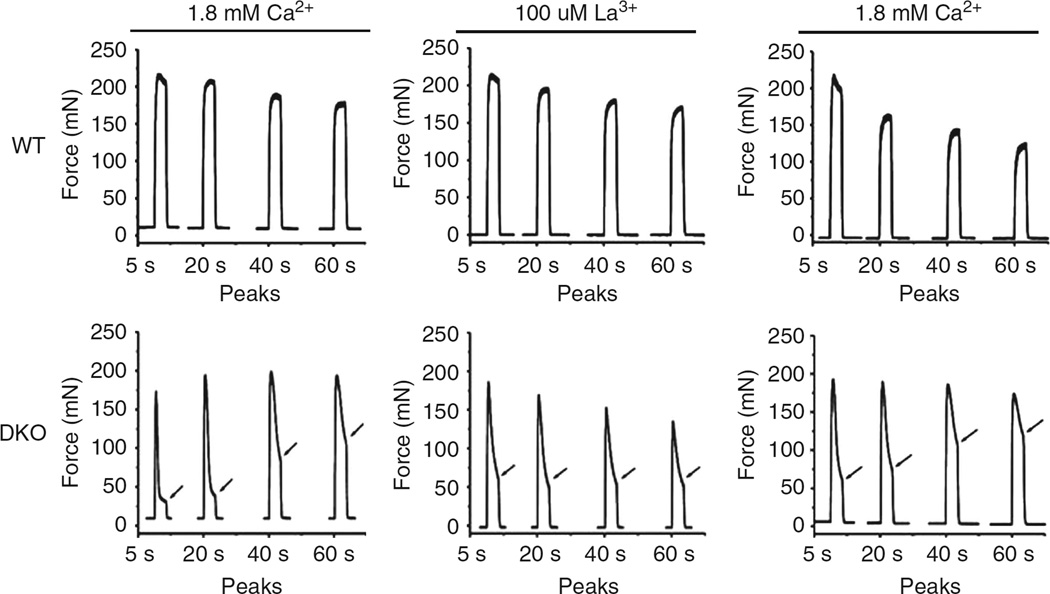

To investigate physiological relevance of the enhanced Cav1.1 channel activity in DKO mice, we measured in vivo muscle performance by assessing spontaneous motor activity (Fig. 4a). Three weeks of training improved skeletal muscle performance in both WT and KO mice, however, the total running distance in JP45 null and CASQ1 null mice was ~ 40km lower compared with WT and DKO mice (139.7 ± 2.90 km, 118.1 ± 2.35 km versus 175.3 ± 2.96 km, 175.5 ± 4.23 km, respectively). The enhanced Cav1.1 channel activity restored muscle performance in DKO mice despite a low degree of atrophy of fast fibres (Supplementary Fig. S3), and may be a signature of improved muscle strength31 mediated by massive Ca2+ influx via Cav1.110. To investigate this, we studied the mechanical properties of intact extensor digitorum longus (EDL) (Fig. 4b). EDL from WT and DKO were stimulated with a train of tetani at 0.27 Hz. The onset maximal tetanic force normalized per muscle cross-sectional area of EDL from WT and DKO were not significantly different (327.86± 117.53 mN versus 364.64 ± 76.22 mN, respectively; mean ± s.d. n = 9), whereas the time course of force development of EDL from DKO was dramatically different compared to those of WT. In DKO mice, the first train of repetitive pulses of 350 ms duration at 100 Hz caused an initial increase of isometric force and then rapidly decayed to ~ 20% of the onset value at the end of the repetitive pulses stimulation (Fig. 4b, arrow middle panel ‘first’). The reduction of force development during trains of action potentials is most likely indicative of poor calcium buffering capacity of SR caused by the ablation of CASQ1, as a similar inability to sustain muscle contraction has been observed in muscles from CASQ1 KO mice24 but not in the EDL muscles from JP45 KO mice27, which have a normal CASQ1 expression level. Ablation of JP45 in a CASQ1 KO background has a remarkable effect on the peak tension after repetitive tetanic trains at 0.27 Hz. We observed that in the EDL from the DKO mice the isometric tension developed at the end of the last pulse of the train increased up to 300% of the initial value while a modest decrease was evident in WT mice (Fig. 4b arrow middle panel ‘last’; lower panels). On the basis of the data reported in Figs. 1 and 3, we reasoned that the ablation of JP45 in the CASQ1 KO background supports a strong calcium influx component mediated by Cav1.1 channel activity which leads to (i) accumulation of intracellular calcium and to (ii) the improvement of the peak force development after trains of tetanic stimulation. We tested this possibility by examining the effect of La3+ on the dynamics of force development of EDL from DKO mice during trains of tetani. As expected incubation of EDL with an external solution containing 100µM La3+ blocked calcium influx, and the increase of isometric force at the end of each train of pulses at 100 Hz in DKO and had no effect on WT muscles (Fig. 4b, lower panels). The effect of La3+ in muscles from DKO mice was reversed by re-exposing EDLs to a bathing solution containing 1.8 mM CaCl2 (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Skeletal muscle performance of WTand DKO mice.

(a) In vivo evaluation of muscle strength. Spontaneous activity in 4–6 week-old WT, DKO, JP45 KO and CASQ1 KO mice individually housed in cages equipped with a running wheel. Data points are expressed as mean ± s.e.m.; n = 10 to 13 mice. Overall ANOVA P-value < 0.0001; multicomparison Dunnet’s ANOVA post test shows difference: WT versus DKO P > 0.05; WT versus JP45 KO P < 0.05; WT versus CASQ1 KO P < 0.01. (b) Evaluation of tetanic force of intact EDL. Top and middle row of panels: EDLs were triggered by field stimulation in bathing solution containing 1.8 mM CaCl2 with a train of repetitive pulses (100 Hz, 350 ms duration) at 0.27 Hz (left panels). Time course of force development of the first and last tetani of the trace displayed in the left panels (middle and right panels). Lower row of panels: after repetitive train stimulation the EDL muscles from control (left panel) and DKO (right panel) mice were incubated for 10 min in a bathing solution containing 100 mM La3+ and were then stimulated with repetitive trains of pulses at 0.27 Hz. Data point represents the force developed at the end of 350 ms duration repetitive pulse stimulation (values are mean ± s.d. n = 8, * P < 0.05 Mann–Whitney). The increase the force developed at the end of tetanic stimulation in EDL from KO mice was abolished by 100µM La3+ a blocker of the calcium influx into muscle fibres (compare DKO Ca2+ versus DKO La3+).

Figure 5. Tetanic contraction of EDL from WT and JP45/CASQ1 double KO mice.

EDL from wild-type and DKO were first incubated in a Tyrode’s solution containing 1.8 mM CaCl2. Maximal tetanic force was triggered by field stimulation 28 with a train of repetitive pulses (100 Hz of 350 ms duration) at 0.27 Hz. Tetani at 5, 20, 40 and 60s are shown. The same stimulation protocols was applied to muscle which were incubated for 10 min in a bathing solution containing 100 µM La3+ (traces WT La3+ and DKO La3+). The increase the force developed at the end of tetanic stimulation in EDL from KO mice was abolished by 100 mM La3+ a blocker of the calcium influx into muscle fibres (compare DKO left panel with middle panel). The effect of La3+ was reversed by 10 min long exposure of EDL muscles to a bathing solution containing Ca2+ (right panels).

Discussion

Here we investigated the role of the JP45/CASQ1 complex on the modulation of Cav1.1 function by analysing the functional properties of skeletal muscle fibres from JP45/CASQ1 DKO mice. Our results show that in DKO mice, calcium transients induced by repetitive action potential are supported by massive calcium influx from the extracellular environment. The massive increase of calcium influx is consistent with an enhancement of the Cav1.1 channel activity because: (1) it is inhibited by nifedipine, a blocker of Cav1.1; (2) it does not correlate with an increase in the expression of other know calcium influx channels such as OraI1, TRPC3 and the neonatal isoform of Cav1.1; (3) is associated with a 45% increase of the Cav1.1 peak calcium current density in intact single FDB fibres. This massive calcium influx via Cav1.1 restores the development of in vitro muscle force of EDL from DKO mice. The maintenance of muscle force in vitro is paralleled by the recovery of muscle performance of DKO mice in vivo. The characterization of the JP45/CASQ1 DKO animal model supports the conclusion that JP45/CASQ1 complex may be a genetically encoded modulator of the Cav1.1 channel activity.

The Cav1.1 complex has a dual function: it acts as (i) voltage sensor which activates, via a mechanical coupling, the RyR, and as (ii) a slow activating voltage-dependent calcium channel. Calcium influx via Cav1.1 channel activity was considered not important for skeletal muscle EC coupling, as it was shown that skeletal muscles can contract for hours in extracellular medium containing very low (sub nM) calcium concentrations11. The idea that skeletal muscle EC coupling is independent from the influx of extracellular calcium was confirmed later by pharmacological and genetic manipulation of Cav1.1 function32–35. However, in evaluating the functional significance of the Cav1.1 channel activity, one can not dismiss results showing that the influx of extracellular calcium in involved in the development of muscle contraction in amphibian and mammalian muscle fibres36,37. This apparent discrepancy might be ascribed to different experimental models and conditions that were used to probe the importance of Cav1.1 channel activity in EC coupling. In this study we exploited the JP45/CASQ1 DKO mouse model to investigate to role of Cav1.1 channel activity during EC coupling and its modulation by JP45/CASQ1 complex. Although we are aware that the JP45/CASQ1 KO mouse model may not recapitulate the physiological setting present in mammalian muscle fibres expressing normal levels of both JP45 and CASQ1, our data provide a strong case as to the potential physiological significance of the Cav1.1 channel activity during EC coupling, at least in mutant muscle fibres. The robust calcium influx via Cav1.1 channel activity which was observed during repetitive action potential in JP45/CASQ1 DKO mice results in better contractile function in vitro and, most importantly, in vivo. Such an effect on muscle contractile function could reflect (i) an indirect global adaptive cellular response to the chronic ablation of two important SR proteins, or (ii) result from the lack of specific regulatory mechanism operated by the JP45/CASQ1 complex on the Cav1.1 channel activity. Although we cannot exclude any of the two possibilities, we are confident that our results clearly indicate the physiological importance of the dual activity of Cav1.1 during EC coupling of the DKO muscle fibres. In this mouse model Cav1.1 clearly operates not only as the voltage sensor that activates RyR (Fig. 2), (ii) but also as calcium influx channel which contribute to maintain an adequate level of releasable SR calcium content during sustained muscle activity evoked by tetanic stimulation (Fig. 3). These data imply that the JP45/CASQ1 complex modulate Cav1.1 channel activity also in normal fibres, in particular, it may operate in those conditions which causes a deficit SR calcium load.

On the basis of these data we propose that JP45/CASQ1 complex is genetically encoded modulator of the Cav1.1. channel activity, and that it constitutes a potential target to devise novel therapeutic strategies against the decline of skeletal muscle strength linked to decreased SR calcium content6,7,12.

Methods

Generation JP45 CASQ1 DKO mice

JP45 KO was obtained as described by Delbono et al.27. CASQ1 KO mice were obtained as described by Paolini et al.26. DKO mice were generated by crossing to each other established JP45 KO and CASQ1 KO lines backcrossed in C57BL6J (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Morphology

Immunohistochemistry of EDL and Soleus was carried out as described by Delbono et al.38. EDL and soleus muscles were embedded in OCT, snap-frozen in isopentane, cryosectioned at the mid-belly region (10 µm) and mounted on coverslips for immunostaining. For staining mounted sections were air dried, treated with PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 2% horse serum for 30 min and incubated overnight at 4–8°C with a PBS solution containing 0.01% Triton X100, 1% BSA, 2% horse serum, 0.5% µg ml−1 anti-mouse slow myosin heavy chain (MAB 1628, Millipore, Billerica, MA), 2µg ml−1 anti rat α-laminin (MAB1914, Millipore). Sections were then washed with PBS for 15 min four times, and incubated at room temperature for 40 min with a PBS containing Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgG Ab (2 µg ml−1) and Cy3 anti rat IgG Ab (0.5 µg ml−1). After incubating in the secondary Ab, sections were washed with PBS for 15 min four times dehydrated with ethanol and mounted using a glycerol medium. Fluorescence images were imaged using a Leica DM5000B fluorescence microscope and analysed with Analysis software package from Soft Imaging System, Muenster, Germany. Image analysis of muscle sections was performed in four steps: (1) determination of the muscle fibre boundaries, (2) determination of the muscle fibre cross-sectional area (3) calculation of the per cent of muscle fibres positive for anti MHC I Ab and (4) determination of the per cent of muscle fibres negative for anti MHC I Ab staining. The muscle fibre cross-sectional area was determined using the minimal ‘Feret’s diameter’ (the minimum distance of parallel tangents at opposing borders of the muscle fibre). High-resolution electron microscopy was carried out as described by Paolini et al.26 Volume and surface of the transverse tubule (TT) network (see Table in Supplementary. Fig. 4) were determined using the well-established stereology point and intersection counting techniques39,4 in EM micrographs taken at × 14,000 of magnification. (a) Measurement of relative fibre volume occupied by TT. After covering the images with an orthogonal array of dots at a spacing of 0.20 µm, the ratio between numbers of dots falling in the TT lumen and the total number of dots covering the whole image represent the relative volume of fibre occupied by the TT. (b) Measurement of TT surface area to volume. The images were covered with two sets of grid lines separated by a distance of 0.24 µm and intersecting at right angles. The frequency of intersections between the membrane of interest (TT profiles) and the grid lines was counted. The ratio of TT surface area to volume was obtained from the formula C/2dP test, where C is the number of intersections, d is the spacing between the grid lines, and P test is the number of grid intersections in the test area.

Gene expression analysis

Expression of neonatal Δ29 isoform of Cav1.1 was detected by semiquantitative RT-PCR41. Total RNA was extracted from homogenized mouse muscle tissues EDL and SOL, and cultured C2C12 myotubes using TRIzol reagent. Eight hundred nanograms of RNA were first reverse transcribed into cDNA; the Cav1.1 cDNA was amplified by PCR using primers29, which span exons 27–34: forward 5′-AGTCGGAGCAGATGAACCAC-3′ and reverse 5′-ATGGCCTTGAACTCATCCAG-3′. The PCR amplification conditions were 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 37 cycles of 94 °C for 40 s, 51 °C for 40 s and 70 °C for 1 min, followed by a 5-min extension at 72 °C. The RT-PCR products encoding the adult and neonatal(Cav1.1Δ29) isoforms are 790-bp long (upper band) and (lower band) 733 bp long, respectively.

Analysis of total SR and muscle strength assessment

Total SR membranes were prepared22 starting from a 20% skeletal muscle total homogenate; this was sedimented at 3,000gmax for 10 min and the resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 15,000gmax for 20 min to remove the myofibrillar protein components. The 15,000gmax supernatant was then centrifuged for 60 min at 100,000gmax to isolate the total SR (microsomal) pellet. SDS-polyacrylamide electrophoresis and western blot of total SR proteins were carried out as described by Anderson et al.22 Blots were probed with a polyclonal primary Ab followed by peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The immunopositive bands were visualized by chemiluminescence using the Super Signal West Dura kit from Thermo Scientific. Densitometry of the immunopositive bands was carried out by using BioRad GelDoc 2000. [3H]-PN200-110 and [3H]-Ryanodine binding was carried out according to Anderson et al.42 Briefly, total SR membranes were incubated for 1 h in the dark in a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM CaCl2 plus protease inhibitor cocktail (ROCHE cat. no. 05892953001) 0 05-5 nM PN200-100 and (+)-[5-methyl-3H]. The samples were then filtered through Whatman glass microfibre GF/B filters by Millipore manifold filtering apparatus, rinsed three times with 5 ml of solution containing 200 mM choline chloride, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, and the radioactivity retained on the filters was determined by liquid scintillation counting. [3H]-ryanodine binding was carried out by incubating total SR membranes for 12–16 h at room temperature with 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 1 M NaCl, 5mM AMP, 20 µM CaCl2, 0.05–10 nM [H]-ryanodine and protease inhibitor cocktail (ROCHE cat. no. 05892953001). Membrane bound [3H]-ryanodine was determined by scintillation counting as described above. Nonspecific binding was evaluated in the presence of 1 mM unlabelled nifedipine and 10 mM unlabelled ryanodine, respectively. Curve fitting was performed using Graph Pad Prism 4 software package. Skeletal muscle performance and mechanical properties of EDL were analysed as described by Debono et al.27 Briefly, animals were individually housed in cages equipped with a running wheel carrying a magnet. Wheel revolutions were registered by a reed sensor connected to an I-7053D Digital-Input module (Spectra AG, Egg, Switzerland), and the revolution counters were read by a standard laptop computer via an I-7520 RS-485—to—RS-232 interface converter (Spectra AG, Egg, Switzerland). Digitized signals were processed by the ‘mouse running’ software developed at Santhera Pharmaceuticals, Liestal, Switzerland. To test force in vitro, EDL muscles were dissected and mounted into a muscle testing set-up (Heidelberg-Scientific Instruments, Heidelberg, Germany). Muscle force was digitized at 4 kHz using an AD Instruments converter and stimulated with 15 V pulses for 0.5 ms. EDL tetanus was recorded in response to 400 ms pulses at 10–120 Hz. Specific force was normalized to the muscle cross-sectional area (CSA) = wet weight (mg)/length (mm) × 1.06 (density mg mm−3).

Cell electrophysiology recordings and optical recording

FDB fibres from WT and DKO mice were enzymatically dissociated, plated and recorded following published procedures43,44. The composition of the pipette solution was (mM): 140 Cs-aspartate; 5 Mg-aspartate2, 10 Cs2EGTA (ethylene glycol-bis(α-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′N′-tetraacetic acid), 10 HEPES (N-[2-hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N′-[2-ethanesulfonic acid]), pH was adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH. The external solution contained (mM): 145 TEA (tetraethylammonium hydroxide)-Cl, 10 CaCl2, 10 HEPES and 0.001 tetrodotoxin. Solution pH was adjusted to 7.4 with TEA.OH. For charge movement recording, calcium current was blocked with the addition of 0.5 Cd 2+ plus 0.3 La 3+ to the external solution. Peak Ca 2+ currents were normalized to membrane capacitance and expressed as Amperes per Farad, whereas intramembrane charge movements were calculated as the integral of the current in response to depolarizing pulses and expressed per membrane capacitance as Coulombs per Farad. Fura-2 Mn2+ quenching in intact FDB fibres was carried out as previoulsy described19,28. Calcium transients were measured by using the low-affinity fuorescent calcium indicator MagFluo445,46. Briefly, changes in the [Ca2+]i induced by supramaximal field stimulation were monitored in FDB fibres loaded with Mag-Fluo-4/AM in Tyrode’s buffer. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (20–22 °C) in the presence of 50 mM N-benzyl-p-toluenesulfonamide (BTS) (Tocris) to minimize movement artefacts. Measurements were carried out with a Nikon ECLIPSE TE2000-U inverted fluorescent microscope equipped with a × 20 magnification objective. Fluorescent signals were capture by a photomultiplier connected to a Nikon Photometer P101 amplifier. Calcium transients were analysed by A Dinstrument Chart5 and Origin.6 programs. Changes in fluorescence were calculated as ΔF/F= (Fmax – Frest)/(Frest). Resting calcium was measured with Indo1 loaded FDB fibres45.

Statistical analysis

We used GraphPad Prims 4.0 software package to perform curve fitting and statistical analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from Swiss Muscle foundation, A.F.M., S.N.F and Department of Biomedicine University Hospital Basel. This study was also supported by Research Grant no. GGP08153 from the Italian Telethon ONLUS Foundation to F.P. and grants from the NIH/NIA (AG13934 and AG15820) to O.D.

Footnotes

Author contributions

B.M. and L.B. developed and monitored mouse colony, collected and analysed calcium measurements data; M.V. collected and analysed expression data; R.L. collected and analysed force measurements data; M.T. and H.T. generated mice model; C.P. and F.P provided CASQ1 KO mice and performed structural analysis; O.D., M.L.M., Z-.M.W., M.M. and G.R. collected and analysed electrophysiological data; S.T. collected and analysed biochemical data; and F.Z. took care of conception and design of the experiments, collection and analysis of biochemical, histochemistry and physiological data, and drafting of the manuscript.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at http://www.nature.com/naturecommunications

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Rios E, Pizarro G. Voltage sensor of excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Physiol. Rev. 1991;71:849–908. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.3.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanabe T, Beam KG, Powell JA, Numa S. Restoration of excitation-contraction coupling and slow calcium current in dysgenic muscle by dihydropyridine receptor complementary DNA. Nature. 1990;336:134–139. doi: 10.1038/336134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franzini-Armstrong C, Jorgensen AO. Structure and development of E-C coupling units in skeletal muscle. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1994;56:509–534. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.002453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manini TM, Clark BC. Dynapenia and aging: an update. J Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2012;67:28–40. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodson S, et al. Muscle wasting in cancer cachexia: clinical implications, diagnosis, and emerging treatment strategies. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011;62:265–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-061509-131248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabbara AA, Allen DG. The role of calcium stores in fatigue of isolated single muscle fibres from the cane toad. J. Physiol. 1999;519:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0169o.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson DC, et al. Ryanodine receptor oxidation causes intracellular calcium leak and muscle weakness in aging. Cell Metab. 2011;14:196–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treves S, et al. Minor sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane components that modulate excitation-contraction coupling in striated muscles. J. Physiol. 2009;587:3071–3079. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.171876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakai J, et al. Enhanced dihydropyridine receptor channel activity in the presence of ryanodine receptor. Nature. 1996;380:72–75. doi: 10.1038/380072a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bannister RA, Pessah IN, Beam KG. The skeletal L-type Ca2 + current is a major contributor to excitation-coupled Ca2 + entry. J. Gen. Physiol. 2008;133:79–91. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong CM, Bezanilla FM, Horowicz P. Twitches in the presence of ethylene glycol bis( -aminoethyl ether)-N,N’-tetracetic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1972;267:605–608. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(72)90194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan Z, et al. Dysfunction of store-operated calcium channel in muscle cells lacking mg29. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:379–383. doi: 10.1038/ncb788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurebayashi N, Ogawa Y. Depletion of Ca2+ in the sarcoplasmic reticulum stimulates Ca2 + entry into mouse skeletal muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 2001;533:185–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0185b.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yarotskyy V, Dirksen RT. Temperature and RyR1 regulate the activation rate of store-operated Ca2 + entry current in myotubes. Biophys. J. 2012;103:202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Launikonis S, Rios S. Store-operated Ca2 + entry during intracellular Ca2 + release in mammalian skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2007;583:81–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allard B, Couchoux H, Pouvreau S, Jacquemond V. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2 + release and depletion fail to affect sarcolemmal ion channel activity in mouse skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2006;575:69–81. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rios E. The cell boundary theorem: a simple law of the control of cytosolic calcium concentration. J. Physiol. Sci. 2010;60:81–84. doi: 10.1007/s12576-009-0069-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen DG, Lamb GD, Westerblad H. Impaired calcium release during fatigue. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008;104:296–330. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00908.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cherednichenko G, et al. Enhanced excitation-coupled calcium entry in myotubes expressing malignant hyperthermia mutation R163C is attenuated by dantrolene. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;73:1203–1212. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.043299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao X, et al. Azumolene inhibits a component of store-operated calcium entry coupled to the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:33477–33486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirata Y, et al. Uncoupling store-operated Ca2+ entry and altered Ca2 + release from sarcoplasmic reticulum through silencing of junctophilin genes. Biophys. J. 2006;90:4418–4427. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.076570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson AA, et al. The junctional SR protein JP-45 affects the functional expression of the voltage-dependent Ca2 + channel Cav1.1. J. Cell Sci. 2006;19:2145–2155. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canato M, et al. Massive alterations of sarcoplasmic reticulum free calcium in skeletal muscle fibers lacking calsequestrin revealed by a genetically encoded probe. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:22326–22331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009168108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olojo RO, et al. Mice null for calsequestrin 1 exhibit deficits in functional performance and sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium handling. PLoS One. 2012;6:e27036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sztretye M, et al. Measurement of RyR permeability reveals a role of calsequestrin in termination of SR Ca(2 + ) release in skeletal muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 2011;138:231–247. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paolini C, et al. Reorganized stores and impaired calcium handling in skeletal muscle of mice lacking calsequestrin-1. J. Physiol. 2007;583:767–784. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delbono O, et al. Loss of skeletal muscle strength by ablation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum protein JP45. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20108–20113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707389104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clementi E, et al. Receptor-activated Ca2+ influx Two independently regulated mechanisms of influx stimulation coexist in neurosecretory PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:2164–2172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuluc P, et al. A Cav1.1 Ca2+ channel splice variant with high conductance and voltage-sensitivity alters EC coupling in developing skeletal muscle. Biophys. J. 2009;96:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fosset M, Jaimovich E, Delpont E, Lazdunski M. [3H]nitrendipine receptors in skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:6086–6092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooks SV, Faulkner JA. Skeletal muscle weakness in old age: underlying mechanisms. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994;26:432–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzales-Serratos H, Valle-Aguilera R, Lathrop DA, Garcia MC. Slow inward calcium currents have no obvious role in muscle excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 1982;298:292–41982. doi: 10.1038/298292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miledi R, Parker I, Zhu PH. Extracellular ions and excitation-contraction coupling in frog twitch muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 1984;351:687–710. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melzer W, Herrmann-Frank A, Lu¨ttgau HC. The role of Ca2+ ions in excitation-contraction coupling of skeletal muscle fibres. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1241:59–116. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(94)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dirksen RT, Beam KG. Role of calcium permeation in dihydropyridine receptor function Insights into channel gating and excitation-contraction coupling. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999;114:393–403. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ildefonse M, Jacquemond V, Rougier O, Renaud JF, Fosset M, Lazdunski M. Excitation contraction coupling in skeletal muscle: evidence for a role of slow Ca2+ channels using Ca2 + channel activators and inhibitors in the dihydropyridine series. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1985;129:904–909. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)91977-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamb GD. Asymmetric charge movement in contracting muscle fibres in the rabbit. J. Physiol. 1986;376:63–83. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delbono O, et al. Endogenously determined restriction of food intake overcomes excitation-contraction uncoupling in JP45KO mice with aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2012;47:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loud AV, Barany WC, Pack BA. Quantitative Evaluation of Cytoplasmic Structures in Electron Micrographs . Lab. Invest. 1965;14:996–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mobley BA, Eisenberg BR. Sizes of components in frog skeletal muscle measured by methods of stereology. J. Gen. Physiol. 1975;66:31–45. doi: 10.1085/jgp.66.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vukcevic M, Spagnoli GC, Iezzi G, Zorzato F, Treves S. Ryanodine receptor activation by Ca v 1.2 is involved in dendritic cell major histocompatibility complex class II surface expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:34913–3422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804472200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson K, Cohn AH, Meissner G. High-affinity [3H]PN200-110 and [3H]ryanodine binding to rabbit and frog skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:C462–C466. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.2.C462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang ZM, Messi ML, Delbono O. Patch-clamp recording of charge movement, Ca2+ current and Ca2 + transients in adult skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys. J. 1999;77:2709–2716. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(99)77104-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herna´ndez-Ochoa EO, Schneider MF. Voltage clamp methods for the study of membrane currents and SR Ca(2 + ) release in adult skeletal muscle fibres. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2012;108:98–118. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hollingworth S, Gee KR, Baylor SM. Low-affinity Ca2+ indicators compared in measurements of skeletal muscle Ca2 + transients. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1864–1872. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calderón JC, Bolaños P, Caputo C. Myosin heavy chain isoform composition and Ca(2+ ) transients in fibres from enzymatically dissociated murine soleus and extensor digitorum longus muscles. J. Physiol. 2010;588:267–279. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.180893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tomasi M, et al. Calsequestrin (CASQ1) rescues function and structure of calcium release units in skeletal muscles of CASQ1-null mice. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C575–C586. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00119.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.