Abstract

Despite being one of the most common conditions leading to gastroenterological referral, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is poorly understood. However, recent years have seen major advances. These include new understanding of the role of both inflammation and altered microbiota as well as the impact of dietary intolerances as illuminated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which has thrown new light on IBS. This article will review new data on how excessive bile acid secretion mediates diarrhea and evidence from post infectious IBS which has shown how gut inflammation can alter gut microbiota and function. Studies of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have also shown that even when inflammation is in remission, the altered enteric nerves and abnormal microbiota can generate IBS-like symptoms. The efficacy of the low FODMAP diet as a treatment for bloating, flatulence, and abdominal discomfort has been demonstrated by randomized controlled trials. MRI studies, which can quantify intestinal volumes, have provided new insights into how FODMAPs cause symptoms. This article will focus on these areas together with recent trials of new agents, which this author believes will alter clinical practice within the foreseeable future.

Keywords: IBS, IBD, MRI studies, FODMAP diet, IBS treatment advances

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common gastroenterological diagnoses, experienced by around 11% of the population. Symptoms consist of abdominal pain associated with erratic bowel habit and variable changes in stool form and frequency, suggesting considerable heterogeneity in underlying mechanisms. Despite IBS’ high prevalence, these mechanisms are poorly understood and treatment is unsatisfactory. This important unmet clinical need is a very active research area. This article will focus on recent significant advances, which this author believes are likely to influence clinical practice within the foreseeable future. These include better understanding of the role of bile acids in causing diarrhea/constipation, significance of alterations in gut microbiota, alterations in enteric innervation and serotonin availability associated with inflammation, IBS-like symptoms in patients with quiescent inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and several new treatments including the low-FODMAP diet, guanylate cyclase C activators, and 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonists.

New insights into mechanisms of IBS symptoms

Bile acids and bowel dysfunction

The laxative properties of bile acids have been recognized since 1868, when ‘liver’ pills composed of ox bile were patented and widely promoted as panacea supplements. Scientific study had to wait until the 1970s, when perfusion studies showed that bile salts stimulated enterocyte secretion and in excess caused diarrhea. Initially, terminal ileal resection was identified as the commonest cause of bile acid diarrhea, but it is now recognized that the negative feedback loop controlling hepatic bile acid production may be disturbed in patients with intact intestines. Bile acids absorbed in the human ileum activate the nuclear receptor farnesoid X to stimulate the production of fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19). This circulates to the liver where, acting via the FGF receptor 4, it inhibits cholesterol 7-hydroxylase (CYP7A1), the rate-limiting enzyme that converts cholesterol to 7α-Hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (C4), an intermediate step in the production of cholic and chenodeoxycholic acid. Decreased circulating FGF19 leading to excessive production of bile acids can be primary or secondary to bile salt malabsorption caused by ileal resection or ileitis. If excessive bile acids enter the colon, they stimulate colonic secretion and increase stool water. A meta-analysis suggests that 10% of patients with IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D)-like symptoms have severe bile acid malabsorption, with <5% retention at 7 days 1. A recent survey in the UK suggests that bile acid diarrhea accounts for nearly one in four of IBS patients referred to secondary care with diarrhea 2.

Identifying patients with overproduction of bile salts used to depend on demonstrating reduced 7-day retention of an artificial radiolabeled bile acid, selenium-75 homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT), the normal being >15%. Retention of <5% is associated with a 96% response to cholestyramine 1, while lesser degrees of malabsorption produce less favorable results, with only 37% responding who have SeHCAT values >5% but <10% 3. Access to SeHCAT is limited worldwide, so the recent demonstration that a fasting FGF19 <145 pg/ml predicts SeHCAT <10% with a negative predictive value of 82% and a positive predictive value of 61% 4 suggests an alternative, which, as it is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), could be widely used unlike older HPLC methods. Newer, more convenient assays for C4 are also being developed. What causes a low FGF19 level in each case remains to be determined, but some cases of bile acid malabsorption begin acutely after an episode of ileitis, which is a common feature of both Salmonella species and Campylobacter jejuni gastroenteritis. Sudden onset associated with high-volume nocturnal diarrhea are characteristic features 5.

The laxative effects of bile acids has been exploited by inhibitors of bile acid uptake such as elobixibat, which reduce FGF19, increase bile acid synthesis, and have been shown in phase II studies to be effective treatments for constipation 6, 7.

The variability in symptoms with bile acid diarrhea suggests individual differences in sensitivity to bile acids. A single nucleotide polymorphism, rs11554825, in the membrane-bound bile acid receptor TGR5 (G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1, also known as GpBAR1) has been suggested to be linked to small bowel and colonic transit, which were faster with TT versus TC/CC variants 8. Further, more detailed studies in a smaller group showed faster colonic transit with both TT and CC TGR5 variants, possibly due to an interaction with klotho β (KLB) 9. However, more work is needed as these studies are underpowered and the functional significance of the rs11554825 variants in TGR5 has yet to be established.

IBS in IBD

IBD, particularly Crohn’s disease, can mimic many IBS symptoms during acute inflammatory flares, but it is increasingly recognized that acute inflammation leaves persistent changes in both nerve and muscle, which leads to IBS-like symptoms, even during remission 10, 11. Occult inflammation can be detected with increases in fecal calprotectin in some cases 12, but that still leaves around one-third with IBS-like symptoms 13. The underlying mechanisms may include altered permeability and ongoing low-level immune activation, as has been shown in the cecal biopsies of IBD patients in apparent remission but with IBS symptoms 14. Other possible mechanisms include persisting alterations in enteric nerves and serotonin signaling (see below). The importance here is to recognize that such symptoms may respond better to IBS treatment including dietary restrictions rather than increasing immunosuppression with all of its inherent risks.

Changes in enteric nerves

Several recent studies have examined mucosal innervation in IBS and found increases in nerves expressing the transient receptor potential vanilloid channel (TRPV1) 15, a peptide associated with pain pathways which also plays a key role in mechanosensitivity 16. TRPV1 is upregulated by inflammation and has been shown to be increased in the rectosigmoid mucosa of IBD patients who continue to experience pain despite apparent disease quiescence 17. Proximity of activated mast cells to enteric nerves has been shown to correlate with severity of abdominal pain in IBS 18, and more recently a study of 101 IBS patient biopsies has shown increased amounts of neural tissue and increases in the growth-associated protein 43 (GAP43). Furthermore, biopsy supernatants increased neurogenesis in primary culture of enteric neurons 19. Whether this stimulation of nerve growth causes the close association of enteric nerves and mast cells and contributes to visceral hypersensitivity in IBS remains to be determined.

Alterations of serotonin transporter

The action of 5-HT at the synapse is terminated by active reuptake of 5-HT by the serotonin transporter (SERT). Several studies in IBS patients have suggested impairment of SERT in both platelets 20 and duodenal mucosa 21, though the evidence in the colon is contradictory, with some reporting a decrease 22, 23 and others no change 24. Many such mechanistic studies use small numbers of patients, so, given the heterogeneity of IBS, conflicting results are not unexpected. The existence of subgroups of patients with abnormally increased or decreased mucosal 5-HT means that while some will respond to 5-HT receptor antagonists, others need 5-HT agonists. A polymorphism in the promoter region of the SERT gene alters SERT efficiency with the long form ll increasing efficiency and being associated with IBS with constipation (IBS-C), while the short form ss is increased in IBS-D 25. Genetic differences in tryptophan hydroxylase-1 enzyme (TPH-1), the rate-limiting step in 5-HT synthesis, has been reported to predict response to 5-HT3 receptor antagonists 26. Similarly, the SERT promoter polymorphism has been reported to predict response to alosetron in IBS-D with sl genotype showing reduced responsiveness 27, but this was not confirmed in a larger trial with ondansetron 28.

New insights from magnetic resonance imaging of the colon and small intestine

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides a unique opportunity to image the undisturbed gut, since by using a range of sequences adequate contrast can be obtained with normal gut contents 29. Such studies have provided for the first time accurate assessments of small bowel and regional colonic volumes in normal subjects. The resting small bowel contains surprisingly little free water, varying in different studies from 50 ml 30 to 150 ml 31. This rises rapidly to around 400 ml after an osmotic stress such as that provided by mannitol 30 or fructose 32 or falls when readily absorbable fluids are provided such as sucrose and glucose 30. High-fat meals, by contrast, cause a rapid rise in small bowel water content probably due to stimulation of pancreaticobiliary secretions 33.

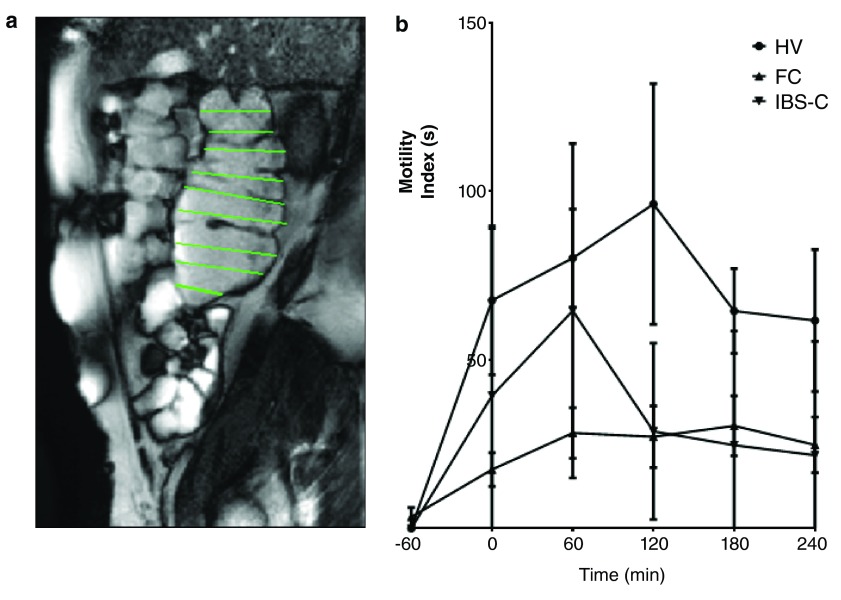

MRI has shown that there is a very wide normal range of colonic volumes with the ascending colon being mean (standard deviation [SD]) 203 (75) ml, transverse colon 232 (100) ml, and descending colon 151 (71) ml, with total colonic volumes being 632 (167) ml. While IBS-D patients have fasting colonic volumes within the normal range, those with functional constipation have significantly increased ascending colon and total colon volumes at 597 (170) and 1505 (387) ml, respectively 34. Interestingly, by contrast, 95% of patients with IBS-C had colonic volumes within the normal range. In addition to fasting scans, it is simple to assess the response to feeding and also to a stronger stimulus provided by the osmotic laxative Moviprep R using cine MRI. This shows marked impairment of colonic motility in functional constipation but not IBS-C ( Figure 1) 34. The technique can also be used to show the mode of action of therapeutic agents including Movicol, loperamide, ondansetron, and ispaghula and could be useful in the future when screening drugs designed to alter colonic transit 29.

Figure 1.

( a) Sagittal magnetic resonance image of ascending colon taken during cine recording. A system of image registration removes the movement due to diaphragmatic movements during respiration. The operator draws lines at right angles to the colonic axis and these lines are automatically propagated through the cine series. The change in line length between time points gives the transverse wall velocity and the motility index (MI) = % of lines at all time points in which the change in transverse wall velocity is >0.5 mm/s. ( b) Motility index of the ascending colon following ingestion of 1L of the osmotic laxative Moviprep commencing at time -60 minutes. This shows the normal rapid increase in motility in healthy volunteers (HV) with markedly impaired response in patients with functional constipation (FC). Irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) patients showed an initially normal response which had faded by the second hour. Data from Lam et al. 34.

Dietary intolerances

Many IBS patients report that their symptoms are aggravated by eating certain foods, and several uncontrolled studies found 36–40% of patients could be helped by selective exclusion of a range of foods often including dairy, wheat, onions, and fruit 35, 36. Double blind exclusion diets are very demanding and few have been done until recently, when a clearer definition of what was being excluded was developed based on the FODMAP concept ( Text Box 1).

| FODMAP concept | |

|---|---|

| •

Fermentable

• Oligosaccharides • Disaccharides • Monosaccharides • AND • Polyhydric alcohols |

- FOS, GOS, fructans, raffinose, inulin - lactose (galactose-glucose) - sucrose (glucose-fructose) - fructose - sorbitol, mannitol, sylitol, maltitol |

| Key features are poor absorption in the small bowel and rapid

fermentation in the colon | |

FODMAP reduction to control IBS symptoms

Systematic application of this diet required the chemical analysis of common foods to identify those that contained significant amounts of these substances. The pioneers were the group in Monash University led by Gibson, a gastroenterologist, and Muir, a biochemist. The most important sources of FODMAPs in the western diet are wheat, onions, and fruit with an excess of fructose over glucose such as apples and pears. Dairy products are also important in those with lactose malabsorption. The first rigorous placebo-controlled diet published in 2014 showed that the low-FODMAP diet improved bloating and abdominal pain/discomfort when compared to the standard Australian diet 37. It should be noted, however, that the low-FODMAP diet does not alter bowel habit consistently and so cannot be expected to benefit those whose main problem is diarrhea or constipation. The low-FODMAP diet has been compared with an ‘IBS diet’ in a randomized trial that showed a similar improvement in symptoms 38. There is some overlap between the two diets, but the ‘IBS diet’ gives more general advice like regular meals and exercise along with avoiding foods thought to promote gas formation without the rigor of a diet based on the chemical composition of food. The complexity of the FODMAP diet makes it difficult to implement, an obstacle which perhaps could be overcome by excluding just the major sources of FODMAPs in any individual’s diet (e.g. wheat, onions, and dairy) and not bothering with items which individually contribute only small amounts or dairy products in those with the lactose persistence genotype 39.

Changes in microbiota

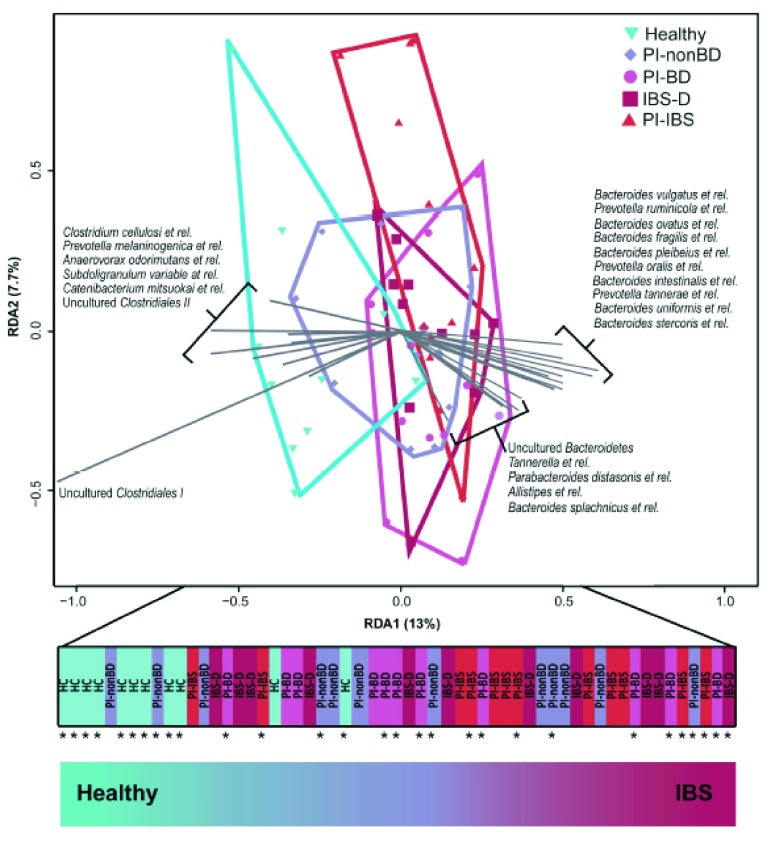

The advances associated with non-culture-based methods of microbiota assessment using ribosomal RNA analysis has led to numerous studies of the microbiota in IBS with somewhat conflicting results (for review, see 40). This is perhaps not surprising, since it is clear that diet and transit are both major determinants of microbiota composition and most studies of the microbiota in IBS have failed to control for these factors 41. Fast transit, such as is seen in IBS-D patients, gives a survival advantage to either organisms that multiply rapidly or those that adhere well to the mucosa 42. This latter study showed that stool consistency was an important predictor of enterotype but did not comment on how consistent this was within an individual. One of the key features of IBS is the erratic pattern of stool form 43, with both hard and loose stool within a time period as short as 24 hours, suggesting that stool microbiota might also be unstable in IBS. A useful study demonstrated that while a subgroup have microbiota that are distinctly different from normal, many IBS patients have microbiota that cluster with normal controls. Interestingly, the group with ‘normal’ microbiota were more likely to have clinically significant depression, suggesting that abnormal microbiota might represent a group with a predominantly peripheral gut abnormality, while normal microbiota might be a signature of those in whom the main abnormality lies centrally 44. Acute gastroenteritis causes a marked disturbance of the gut microbiota with overgrowth of pathogen and a marked reduction in diversity. This is followed by a return towards the former equilibrium but, as recently shown, distinct differences remain after Campylobacter jejuni enteritis, the commonest cause of food poisoning in the UK. Restricting analysis to just 27 genus-like taxa, we showed in a redundancy analysis that the individuals could be ordered on the primary axis from health at one end to IBS at the other with infected but recovered individuals in between 45 ( Figure 2).

Figure 2. Redundancy analysis using 27 genus-like taxa to separate 1) healthy controls from 2) individuals who had had Campylobacter but recovered with no bowel disturbance (PI-nonBD), 3) individuals who had had Campylobacter but with persistent bowel disturbance (PI-BD), 4) individuals with post infectious IBS (PI-IBS), and 5) individuals with IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D).

The primary axis was used as an index of dysbiosis, which separates these groups in a graded fashion from health to disease. Reproduced from Jalanka et al. 45.

Evidence of abnormal small bowel microbiota

This is an area of considerable confusion, largely because there is a gradient of bacterial density within the small bowel ranging from 10 -1 ml in the duodenum to 10 7 ml in the terminal ileum. Identifying an abnormal increase in luminal bacteria requires defining this gradient throughout the small bowel, something which current tests cannot do. Intubation and analysis of aspirates give a single value, usually from the jejunum. Using such a test, values exceeding the accepted threshold of 10 5/ml are found in around 4% of both controls and IBS patients 46. Lactulose breath hydrogen tests (LBHTs) alone are impossible to interpret, as one can rarely exclude the possibility that any early rise in breath hydrogen observed is due to lactulose reaching the cecum. However, this can, to some extent, be overcome by combining with scintigraphic assessment of orocecal transit (SOCT), which gives a time when >5% of isotope has entered the colon. If the breath hydrogen rise occurs before this time then it is usually interpreted as showing abnormal microbiota in the small bowel. However, it should be noted that this requires that breath hydrogen would not rise if <5%, i.e. 0.5 g, had entered the colon, which is an unproven assumption, as this amount of lactulose will produce 16 ml of hydrogen 47, which, depending on the rate of excretion, could raise breath hydrogen by much more than the 10 parts per million required for a positive test. The terminal ileum is an area where the stasis which favors growth of colonic anaerobes is often observed, especially during fasting 48, so this is most likely to be the site where microbiota would proliferate. A recent study using this technique suggested that around one-third of IBS patients attending a Chinese outpatient clinic have a positive LBHT/SOCT, though it is unclear how these were selected or whether this finding is generalizable to other clinics. A positive test did seem to predict a better response to rifaximin, but these studies need repeating as the numbers were very small 49. These values are comparable with a previous large study using the glucose breath hydrogen test, which reported positive tests in 31% of 65 IBS patients versus 4% in 105 healthy controls 50.

Biomarkers of disease mechanism

Where the history is confusing, colonic transit may be helpful in predicting response to drugs accelerating or retarding transit 51. Low SeHCAT values predict response to cholestyramine, but otherwise there are currently few other biomarkers in clinical use that can predict response to specific therapies. Measures of visceral sensitivity do not appear to predict response to ketanserin, even though this did increase the threshold for discomfort during a barostat study 52. Genetic tests might fare better, but preliminary reports suggesting TPH-1 polymorphisms predict response to ramosetron need confirmation in larger studies 26. Genetic testing for lactose intolerance could replace LBHT, being more convenient and highly sensitive 53. Though interesting mechanistically, the mucosal biopsy assays including histology and mediator release show such wide variability that none so far are useful diagnostically nor in predicting treatment response.

Advances in treatment for IBS

Opioids for IBS-D

Loperamide is a safe and effective anti-diarrheal agent, which has been shown in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to reduce bowel frequency in IBS-D but with little benefit on pain 54, which may actually increase 55. Despite this, loperamide improves quality of life since it allows planning of trips and socializing, which anxious IBS-D patients often avoid for fear of fecal urgency or even incontinence. More recently, eluxadoline, a mu-opioid receptor agonist with delta-opioid receptor antagonistic action, has been shown in a large, high-quality phase IIb dose-finding RCT to benefit IBS-D with a 14% increase in responder rates (28% versus 14%) after 12 weeks of either 100 or 200 mg twice daily 56. However, this mode of action does carry a risk of causing acute pancreatitis through sphincter of Oddi spasm, which may prove unacceptable in IBS.

5-HT3 receptor antagonists for IBS-D: alosetron, ramosetron, and ondansetron

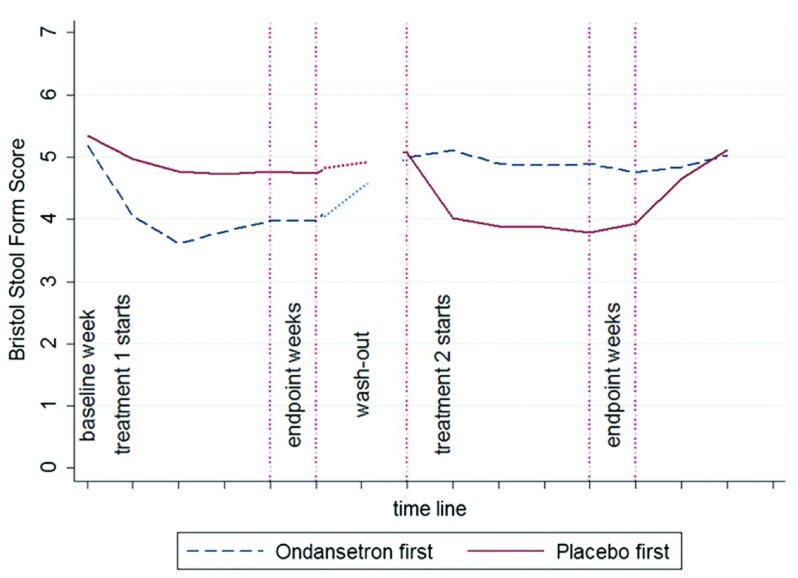

5-HT3 receptor antagonists (5-HT3RAs) are effective treatments for IBS-D 57, slowing transit, reducing bowel frequency, normalizing stool consistency, and reducing urgency 58, which is one of the key symptoms that impair quality of life in IBS-D. Alosetron has been shown to significantly improve quality of life 59. Constipation is a common side effect, which was reported in around 25% of those given standard doses of alosetron. While this can be controlled by dose reduction, this is not true of ischemic colitis, a much rarer side effect, which was seen in around one in 700 patients 60, 61. Although not life threatening, ischemic colitis led to alosetron’s withdrawal from general marketing, though now it is off patent, use may increase. Ramosetron is effective at a very low dose, 5 µg in men 62, 63 and 2.5 µg in women 64, with an acceptably low rate of constipation and no reports of ischemic colitis. Recently, the much less potent 5-HT3RA ondansetron, given at a dose of 4 mg, range 2–6 mg, was shown to be highly effective at improving stool consistency ( Figure 3), reducing stool frequency and reducing urgency, with 70% reporting adequate relief of IBS symptoms on ondansetron compared to 16% on placebo, giving a number needed to treat (NNT) of two 28. It is worth noting that ondansetron has been used for over two decades with no reports of ischemic colitis and has an excellent safety record, a feature which is so important for IBS medication.

Figure 3. The time course of stool consistency during randomized cross-over.

Stool form score fell into the normal range 3–5 within 1 week of starting ondansetron, rapidly returning to baseline on discontinuation. There was very little placebo response. Reproduced from Garsed et al. 28.

Secretagogues

Recently, two new secretagogues, lubiprostone and linaclotide, have been introduced for the treatment of both chronic constipation and IBS-C. Both are supported by large RCTs performed to high standards 65– 68. Lubiprostone stimulates chloride secretion by activating the type 2 chloride ion channel 69. It does not alter pain thresholds during rectal distension using a barostat 70 but does accelerate transit in healthy volunteers 71. It relieves overall IBS-C symptoms with 17.9% responder rate compared to 10.1% with placebo and this is associated with modest reductions in pain and straining 65. This gives a NNT of 13. Around 25% of patients experience nausea, but only around 5% discontinue its use because of this. Linaclotide also stimulates chloride secretion by activating the guanylate cyclase C receptor, increasing cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), an important intracellular second messenger that activates the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) to cause chloride secretion 72. Linaclotide, 290 µg daily, improved both pain and stool consistency in a 12-week trial of 800 IBS-C patients, meeting the FDA guidelines in 33.6% compared to 21% on placebo, giving an NNT of eight 73. The benefit persisted in another 26-week trial 67. Both trials showed improvement in stool consistency and frequency within the first week, while abdominal discomfort continued to improve over a period of about 6 weeks. The main side effect is diarrhea, experienced in 19.7%, severe in 2%, and leading to drug discontinuation in 4.5% 6.

Future directions

The heterogeneity of IBS means that future studies must aim to be larger and more mechanistic than in the past. There are too many small studies performed by isolated research groups with contradictory conclusions. These will be resolved only by larger multicenter studies involving consortia of researchers from many different areas. Such studies should include not only symptom responses but also measurement of relevant biomarkers, which will confirm or refute potential mechanisms. Our current symptom-based criteria for study entry led to small differences from placebo in therapeutic trials because similar symptoms can arise from more than one mechanism. We should subdivide our patients by the mechanisms discussed above and use as entry criteria to trials so that therapies are targeted to those who can benefit, with a potential for reducing the time and cost of developing new effective therapies. Better biomarkers more directly assessing the disturbance in function being targeted will help in this process.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

William Chey, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

Anton Emmanuel, Department of Internal Medicine, University College London, London, UK

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 1; referees: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Wedlake L, A'Hern R, Russell D, et al. : Systematic review: the prevalence of idiopathic bile acid malabsorption as diagnosed by SeHCAT scanning in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(7):707–717. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04081.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 2. Aziz I, Mumtaz S, Bholah H, et al. : High Prevalence of Idiopathic Bile Acid Diarrhea Among Patients With Diarrhea-predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome Based on Rome III Criteria. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(9):1650–5.e2. 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 3. Williams AJ, Merrick MV, Eastwood MA: Idiopathic bile acid malabsorption--a review of clinical presentation, diagnosis, and response to treatment. Gut. 1991;32(9):1004–1006. 10.1136/gut.32.9.1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pattni SS, Brydon WG, Dew T, et al. : Fibroblast growth factor 19 in patients with bile acid diarrhoea: a prospective comparison of FGF19 serum assay and SeHCAT retention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(8):967–976. 10.1111/apt.12466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 5. Sinha L, Liston R, Testa HJ, et al. : Idiopathic bile acid malabsorption: qualitative and quantitative clinical features and response to cholestyramine. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12(9):839–844. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chey WD, Camilleri M, Chang L, et al. : A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Phase IIb Trial of A3309, A Bile Acid Transporter Inhibitor, for Chronic Idiopathic Constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(10):1803–1812. 10.1038/ajg.2011.162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 7. Simrén M, Bajor A, Gillberg PG, et al. : Randomised clinical trial: The ileal bile acid transporter inhibitor A3309 vs. placebo in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation--a double-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(1):41–50. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04675.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 8. Camilleri M, Vazquez-Roque MI, Carlson P, et al. : Association of bile acid receptor TGR5 variation and transit in health and lower functional gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23(11):995–9, e458. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01772.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 9. Camilleri M, Shin A, Busciglio I, et al. : Genetic variation in GPBAR1 predisposes to quantitative changes in colonic transit and bile acid excretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307(5):G508–G516. 10.1152/ajpgi.00178.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 10. Halpin SJ, Ford AC: Prevalence of symptoms meeting criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(10):1474–1482. 10.1038/ajg.2012.260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 11. Spiller R, Lam C: The shifting interface between IBS and IBD. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11(6):586–592. 10.1016/j.coph.2011.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keohane J, O'Mahony C, O'Mahony L, et al. : Irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a real association or reflection of occult inflammation? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(8):1788, 1789–94; quiz 1795. 10.1038/ajg.2010.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 13. Berrill JW, Green JT, Hood K, et al. : Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: examining the role of sub-clinical inflammation and the impact on clinical assessment of disease activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(1):44–51. 10.1111/apt.12335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vivinus-Nébot M, Frin-Mathy G, Bzioueche H, et al. : Functional bowel symptoms in quiescent inflammatory bowel diseases: role of epithelial barrier disruption and low-grade inflammation. Gut. 2014;63(5):744–752. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 15. Akbar A, Yiangou Y, Facer P, et al. : Increased capsaicin receptor TRPV1-expressing sensory fibres in irritable bowel syndrome and their correlation with abdominal pain. Gut. 2008;57(7):923–929. 10.1136/gut.2007.138982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 16. Jones RC, 3rd, Otsuka E, Wagstrom E, et al. : Short-term sensitization of colon mechanoreceptors is associated with long-term hypersensitivity to colon distention in the mouse. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(1):184–194. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akbar A, Yiangou Y, Facer P, et al. : Expression of the TRPV1 receptor differs in quiescent inflammatory bowel disease with or without abdominal pain. Gut. 2010;59(6):767–774. 10.1136/gut.2009.194449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 18. Barbara G, Stanghellini V, De Giorgio R, et al. : Activated mast cells in proximity to colonic nerves correlate with abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(3):693–702. 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dothel G, Barbaro MR, Boudin H, et al. : Nerve fiber outgrowth is increased in the intestinal mucosa of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(5):1002–1011.e4. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 20. Bellini M, Rappelli L, Blandizzi C, et al. : Platelet serotonin transporter in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome both before and after treatment with alosetron. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(12):2705–2711. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08669.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foley S, Garsed K, Singh G, et al. : Impaired uptake of serotonin by platelets from patients with irritable bowel syndrome correlates with duodenal immune activation. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(5):1434–43.e1. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 22. Coates MD, Mahoney CR, Linden DR, et al. : Molecular defects in mucosal serotonin content and decreased serotonin reuptake transporter in ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(7):1657–1664. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kerckhoffs AP, ter Linde JJ, Akkermans LM, et al. : SERT and TPH-1 mRNA expression are reduced in irritable bowel syndrome patients regardless of visceral sensitivity state in large intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302(9):G1053–G1060. 10.1152/ajpgi.00153.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Camilleri M, Andrews CN, Bharucha AE, et al. : Alterations in expression of p11 and SERT in mucosal biopsy specimens of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(1):17–25. 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 25. Wang YM, Chang Y, Chang YY, et al. : Serotonin transporter gene promoter region polymorphisms and serotonin transporter expression in the colonic mucosa of irritable bowel syndrome patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(6):560–565, e254–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01902.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 26. Shiotani A, Kusunoki H, Ishii M, et al. : Pilot study of Biomarkers for predicting effectiveness of ramosetron in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: expression of S100A10 and polymorphisms of TPH1. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(1):82–91. 10.1111/nmo.12473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 27. Camilleri M, Atanasova E, Carlson PJ, et al. : Serotonin-transporter polymorphism pharmacogenetics in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(2):425–432. 10.1053/gast.2002.34780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Garsed K, Chernova J, Hastings M, et al. : A randomised trial of ondansetron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Gut. 2014;63(10):1617–1625. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 29. Khalaf A, Hoad CL, Spiller RC, et al. : Magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers of gastrointestinal motor function and fluid distribution. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2015;6(4):140–149. 10.4291/wjgp.v6.i4.140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marciani L, Cox EF, Hoad CL, et al. : Postprandial changes in small bowel water content in healthy subjects and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(2):469–77, 477.e1. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 31. Marciani L, Wright J, Foley S, et al. : Effects of a 5-HT 3 antagonist, ondansetron, on fasting and postprandial small bowel water content assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(5):655–663. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Murray K, Wilkinson-Smith V, Hoad C, et al. : Differential effects of FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols) on small and large intestinal contents in healthy subjects shown by MRI. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(1):110–119. 10.1038/ajg.2013.386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hussein MO, Hoad CL, Wright J, et al. : Fat emulsion intragastric stability and droplet size modulate gastrointestinal responses and subsequent food intake in young adults. J Nutr. 2015;145(6):1170–1177. 10.3945/jn.114.204339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lam C, Chaddock G, Marciani L, et al. : Colonic response to laxative ingestion as assessed by MRI differs in constipated irritable bowel syndrome compared to functional constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016. 10.1111/nmo.12784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nanda R, James R, Smith H, et al. : Food intolerance and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1989;30(8):1099–1104. 10.1136/gut.30.8.1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Parker TJ, Naylor SJ, Riordan AM, et al. : Management of patients with food intolerance in irritable bowel syndrome: The development and use of an exclusion diet. J Human Nutrition Dietetics. 1995;8(3):159–166. 10.1111/j.1365-277X.1995.tb00308.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, et al. : A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):67–75.e5. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 38. Bohn L, Storsrud S, Liljebo T, et al. : Diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome as well as traditional dietary advice: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1399–1407.e2. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 39. Pohl D, Savarino E, Hersberger M, et al. : Excellent agreement between genetic and hydrogen breath tests for lactase deficiency and the role of extended symptom assessment. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(6):900–907. 10.1017/S0007114510001297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simrén M, Barbara G, Flint HJ, et al. : Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: a Rome foundation report. Gut. 2013;62(1):159–176. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 41. Rajilic-Stojanovic M, Jonkers DM, Salonen A, et al. : Intestinal microbiota and diet in IBS: causes, consequences, or epiphenomena? Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(2):278–287. 10.1038/ajg.2014.427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vandeputte D, Falony G, Vieira-Silva S, et al. : Stool consistency is strongly associated with gut microbiota richness and composition, enterotypes and bacterial growth rates. Gut. 2016;65(1):57–62. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pimentel M, Hwang L, Melmed GY, et al. : New clinical method for distinguishing D-IBS from other gastrointestinal conditions causing diarrhea: the LA/IBS diagnostic strategy. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(1):145–149. 10.1007/s10620-008-0694-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jeffery IB, O'Toole PW, Ohman L, et al. : An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut. 2012;61(7):997–1006. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 45. Jalanka-Tuovinen J, Salojarvi J, Salonen A, et al. : Faecal microbiota composition and host-microbe cross-talk following gastroenteritis and in postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2014;63(11):1737–1745. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 46. Posserud I, Stotzer PO, Bjornsson ES, et al. : Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2007;56(6):802–808. 10.1136/gut.2006.108712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 47. Christl SU, Murgatroyd PR, Gibson GR, et al. : Production, metabolism, and excretion of hydrogen in the large intestine. Gastroenterology. 1992;102(4 Pt 1):1269–1277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Spiller RC, Brown ML, Phillips SF: Emptying of the terminal ileum in intact humans. Influence of meal residue and ileal motility. Gastroenterology. 1987;92(3):724–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhao J, Zheng X, Chu H, et al. : A study of the methodological and clinical validity of the combined lactulose hydrogen breath test with scintigraphic oro-cecal transit test for diagnosing small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in IBS patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26(6):794–802. 10.1111/nmo.12331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 50. Lupascu A, Gabrielli M, Lauritano EC, et al. : Hydrogen glucose breath test to detect small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a prevalence case-control study in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(11–12):1157–1160. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02690.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 51. Spiller RC: Potential biomarkers. Gastroenterol Clin North Am.In: Chey WD, editor. Irritable bowel syndrome. 40 ed. Elsevier;2011;40(1):121–139. 10.1016/j.gtc.2011.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Klooker TK, Braak B, Koopman KE, et al. : The mast cell stabiliser ketotifen decreases visceral hypersensitivity and improves intestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2010;59(9):1213–1221. 10.1136/gut.2010.213108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 53. Krawczyk M, Wolska M, Schwartz S, et al. : Concordance of genetic and breath tests for lactose intolerance in a tertiary referral centre. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2008;17(2):135–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lavö B, Stenstam M, Nielsen AL: Loperamide in treatment of irritable bowel syndrome--a double-blind placebo controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1987;130:77–80. 10.3109/00365528709091004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Efskind PS, Bernklev T, Vatn MH: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial with loperamide in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(5):463–468. 10.3109/00365529609006766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dove LS, Lembo A, Randall CW, et al. : Eluxadoline benefits patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea in a phase 2 study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(2):329–338.e1. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 57. Andresen V, Montori VM, Keller J, et al. : Effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) type 3 antagonists on symptom relief and constipation in nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(5):545–555. 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lembo AJ, Olden KW, Ameen VZ, et al. : Effect of alosetron on bowel urgency and global symptoms in women with severe, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: analysis of two controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(8):675–682. 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00284-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cremonini F, Nicandro JP, Atkinson V, et al. : Randomised clinical trial: alosetron improves quality of life and reduces restriction of daily activities in women with severe diarrhoea-predominant IBS. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(5):437–448. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05208.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 60. Chang L, Chey WD, Harris L, et al. : Incidence of ischemic colitis and serious complications of constipation among patients using alosetron: systematic review of clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(5):1069–1079. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00459.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chang L, Tong K, Ameen V: Ischemic colitis and complications of constipation associated with the use of alosetron under a risk management plan: clinical characteristics, outcomes, and incidences. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(4):866–875. 10.1038/ajg.2010.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chiba T, Yamamoto K, Sato S: Long-term efficacy and safety of ramosetron in the treatment of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2013;6:123–128. 10.2147/CEG.S32721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 63. Matsueda K, Harasawa S, Hongo M, et al. : A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of the effectiveness of the novel serotonin type 3 receptor antagonist ramosetron in both male and female Japanese patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(10):1202–1211. 10.1080/00365520802240255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 64. Fukudo S, Kinoshita Y, Okumura T, et al. : Ramosetron Reduces Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Diarrhea and Improves Quality of Life in Women. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(2):358–366.e8. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 65. Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF, et al. : Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome--results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(3):329–341. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03881.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 66. Chey WD, Drossman DA, Johanson JF, et al. : Safety and patient outcomes with lubiprostone for up to 52 weeks in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(5):587–599. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04983.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 67. Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Lavins BJ, et al. : Linaclotide for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: a 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(11):1702–1712. 10.1038/ajg.2012.254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 68. Lembo AJ, Schneier HA, Shiff SJ, et al. : Two randomized trials of linaclotide for chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):527–536. 10.1056/NEJMoa1010863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 69. Rivkin A, Chagan L: Lubiprostone: chloride channel activator for chronic constipation. Clin Ther. 2006;28(12):2008–2021. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Gangarosa L, et al. : Lubiprostone does not influence visceral pain thresholds in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23(10):944–e400. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01776.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Camilleri M, Bharucha AE, Ueno R, et al. : Effect of a selective chloride channel activator, lubiprostone, on gastrointestinal transit, gastric sensory, and motor functions in healthy volunteers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290(5):G942–G947. 10.1152/ajpgi.00264.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 72. Busby RW, Kessler MM, Bartolini WP, et al. : Pharmacologic properties, metabolism, and disposition of linaclotide, a novel therapeutic peptide approved for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and chronic idiopathic constipation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;344(1):196–206. 10.1124/jpet.112.199430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 73. Rao S, Lembo AJ, Shiff SJ, et al. : A 12-week, randomized, controlled trial with a 4-week randomized withdrawal period to evaluate the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(11):1714–1724; quiz p.1725. 10.1038/ajg.2012.255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation