Abstract

Objective:

The objective of the WHO/US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief consultation was to discuss innovative strategies, offer guidance, and develop a comprehensive policy framework for implementing quality-assured HIV-related point-of-care testing (POCT).

Methods:

The consultation was attended by representatives from international agencies (WHO, UNICEF, UNITAID, Clinton Health Access Initiative), United States Agency for International Development, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief Cooperative Agreement Partners, and experts from more than 25 countries, including policy makers, clinicians, laboratory experts, and program implementers.

Main outcomes:

There was strong consensus among all participants that ensuring access to quality of POCT represents one of the key challenges for the success of HIV prevention, treatment, and care programs. The following four strategies were recommended: implement a newly proposed concept of a sustainable quality assurance cycle that includes careful planning; definition of goals and targets; timely implementation; continuous monitoring; improvements and adjustments, where necessary; and a detailed evaluation; the importance of supporting a cadre of workers [e.g. volunteer quality corps (Q-Corps)] with the role to ensure that the quality assurance cycle is followed and sustained; implementation of the new strategy should be seen as a step-wise process, supported by development of appropriate policies and tools; and joint partnership under the leadership of the ministries of health to ensure sustainability of implementing novel approaches.

Conclusion:

The outcomes of this consultation have been well received by program implementers in the field. The recommendations also laid the groundwork for developing key policy and quality documents for the implementation of HIV-related POCT.

Keywords: misdiagnosis, partnerships, point of care testing, quality assurance cycle, volunteer quality corps

Introduction

There has been significant progress in expanding HIV prevention, treatment, and care programs over the past decade [1]. Despite these gains there are still challenges across the continuum of treatment and care cascade beginning with diagnosis, initiation of treatment, and clinical monitoring. There is a significant proportion of undiagnosed HIV cases, which prevents individuals from having access to existing prevention and treatment services. There are an estimated 35 million individuals living with HIV worldwide; 54% (19 million) do not know their HIV-positive status, and only 42% of children born to HIV-positive mothers receive an HIV test within the first 8 weeks of life in low and middle-income countries [2]. The coverage of people on antiretroviral therapy remains low; the percentage of people with HIV not on antiretroviral therapy decreased by only 27% from 90% in 2006 to 63% in 2013, with only 28% of children on antiretroviral therapy worldwide [2]. Furthermore, with the new Joint United Nations Program on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) treatment targets of ‘90 × 90 × 90 by 2020’, which is: 90% of all people living with HIV know their status; 90% of all people diagnosed with HIV are on sustained antiretroviral therapy, and 90% of all people receiving antiretroviral therapy have viral suppression [3], there are still significant gaps to be overcome to reach each of the targets. The recently launched diagnostics access initiative emphasizes that to achieve these targets there will be a need to develop innovative strategies that expand access to affordable diagnostic assays followed by immediate access to effective prevention, treatment, and care programs [4].

Point-of-care testing has the potential to increase access to patient diagnosis and treatment if properly deployed. There is a plethora of HIV-related point-of-care diagnostics (HIV rapid diagnostic tests, CD4+ enumeration, early infant diagnosis, viral load), syphilis, malaria, cryptococcal infection, and tuberculosis [5,6]. Although these technologies have been scaled-up rapidly worldwide, corresponding quality assurance programs have not kept pace. Unfortunately, these inadequacies may partly be responsible for HIV misdiagnosis with significant psychosocial and program consequences [7,8]. In HIV programs in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, and Ethiopia, 10.3, 2.6, and 4.7% false positive HIV results, respectively, were given to participants with devastating consequences of abandonment by partners and inappropriate initiation on treatment [9]. Also, high rates (10.5%) of false-positive were observed in large voluntary counseling and testing program centers in Democratic Republic of Congo using HIV rapid test parallel testing [10]. HIV misdiagnosis and inappropriate initiation of individuals on treatment led WHO to reinforce its retesting strategy on newly diagnosed individuals prior to initiation on antiretroviral therapy [11,12].

Point-of-care testing (POCT) would be indispensable in realizing the efforts of nations and partners to achieve an AIDS-free generation through the implementation of ‘test and treat strategies’; identifying pregnant women for option B+; and attaining the UNAIDS 90 × 90 × 90 goals percentage of people on treatment and virally suppressed by 2020 [3,11]. For instance, HIV rapid diagnostic tests are one of the most widely used POCT for screening individuals. In 2012 WHO estimated HIV testing and counseling of more than 118 million individuals in low and middle-income countries [13]. The large number of POCT performed creates major challenges for program managers and implementers, and thus requires innovative quality assurance strategies to ensure the accuracy and reliability of test results.

The paper reviews the objectives and outcomes of several international consultations on quality of HIV-related POCT following the initial consultation in Atlanta. The objectives of the meeting were to discuss innovative strategies for quality assurance, offer guidance, and develop a comprehensive policy framework for implementing quality-assured HIV-related POCT.

Consultation

Cognizant of the quality challenges associated with large-scale use of POCT, WHO, CDC, and President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) coorganized a stakeholder consultation on ‘Innovative Strategies to Ensure the Quality of HIV-Related Point-of-Care Testing (POCT).’ The meeting held on February 27–28, 2014, brought together representatives from international agencies (WHO, UNICEF, UNITAID, CHAI, USAID, CDC/PEPFAR Cooperative Agreement Partners) and 126 experts from a wide-ranging background, including those with extensive experience in implementing programs, developing policies, and diagnostic experts to discuss novel strategies to implement effective and comprehensive quality assurance programs for HIV-related POCT. The consultation format included a series of technical sessions in which experts provided presentations and experience in aspects of ensuring the quality of HIV rapid and POCT programs. After each session the participants worked in small technical working groups (TWGs) to discuss and develop key points to be considered by partners in the development and implementation of this strategy, which were discussed and adopted at the final closing session.

Main outcomes and recommendations

After two days of discussions, including presentations and sharing of field experiences, participants reached consensus on five points:

Endorse the concept of the quality assurance cycle (QAC) which at a minimum includes proficiency testing program, site support visits, collection and analysis of data, and ensuring corrective actions are accomplished.

Employ strategies that include the development of a new cadre of workers (e.g. Q-Corps as community-based champions) to promote the accomplishment of the QAC.

Adopt a step-wise process for continuous improvement of HIV-related POCT which would lead to certification of individuals and sites.

Advocate for implementation of quality-assured POCT and finalization of policy framework developed at the African Society of Laboratory Medicine (ASLM)/Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)/WHO joint meeting in Tanzania, June 2014.

Support the Ministry of Health (MOH) Ministerial Panel endorsement for accuracy of HIV-related POCT diagnosis at ASLM 2014.

Promoting innovation to increase the uptake, coverage, and impact of the quality-assured HIV-related point-of-care testing

With the large increase in the use of HIV-related POCT, there is the need for new ways to monitor and strengthen testing sites to ensure quality results. The discussions focused on innovative strategies to ensure completion of the QAC. The major conclusions are described here.

The quality assurance cycle

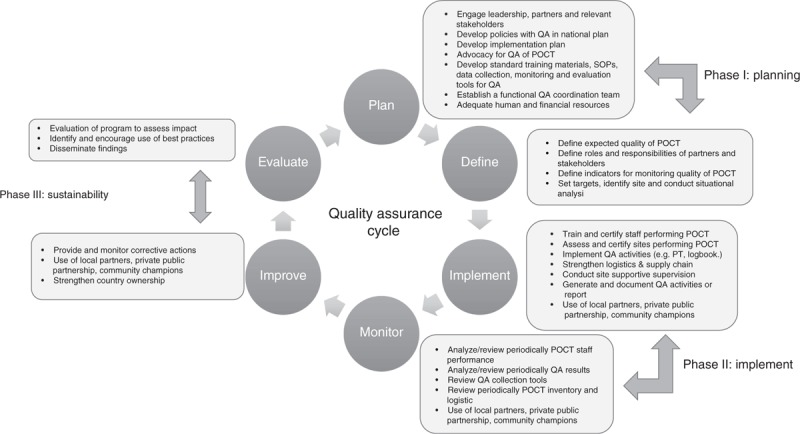

The QAC entails three major phases (Fig. 1) with specific tasks. The emphasis on the QAC is to ensure the whole cycle or activities of the various phases are completed. The quest for completing the QAC cycle was partly informed by field experiences, instances when quality indicators (e.g. proficiency testing) were being implemented but the data or results were not collected and/or analyzed and used for corrective actions, as needed, for program improvement. The inability to complete the whole QAC and focusing only on increased coverage, made this exercise more of a quantity-oriented rather than its intended quality-oriented purpose. It is critical that each quality indicator being implemented goes through all the phases. For example, the dried tube specimen (DTS) proficiency testing panel program should be planned with baseline and target number of sites established. Then implementation through training and monitoring, including the use of MOH staff or local partners and Q-Corps, followed by improvement through site support visits with corrective actions. Finally, the program should be evaluated for impact by the MOH and/or through local implementing partners or institutions. These sequential phases with the use of innovative strategies will ensure that the QAC is completed with impact on reducing the rate of misdiagnoses.

Fig. 1.

The quality assurance cycle depicting the three main phases: plan (phase I), implement (phase II), and sustain (phase III), with roles and activities (shown in boxes) for each phase for HIV-related point-of-care testing quality system.

POCT, point-of-care testing; PT, proficiency testing; QA, quality assurance.

Volunteer quality corps or community-based champions

One of the main challenges experienced in the field with completing the QAC has been the shortage of human resources that are required to ensure completion of the necessary tasks of the QAC. An approach of engaging a new cadre of community-based champions, the Q-Corps, was discussed and endorsed. The Q-Corps concept is modeled on the US Peace Corps program used to support and improve community projects in various departments including health, agriculture, and education. The Q-Corps would be mobilized from the community through an advertisement, for example, in a local newspaper, which would list the minimum standards required for performing duties associated with QAC. The Q-Corps could, for instance, be graduates from medical laboratory training schools or universities, other healthcare professionals, preferably with a background in natural sciences. One of their roles would be to work directly with testing sites on various activities or tasks to improve the quality of testing at the site.

Prior to commencement, the Q-Corps would undergo standard training for two weeks on HIV testing algorithm, QAC, practical hands-on experience and interpretation of results, quality assurance, documentation, safety, troubleshooting, and how to assess testing sites using a standard checklist. Tasks the Q-Corps would perform include:

distribution of proficiency testing panels;

collection of proficiency testing results from enrolled labs and their analysis;

training on correct utilization of standard HIV logbook for data collection;

entry and analysis of standard logbook data; and,

relaying site challenges to appropriate MOH officials or department.

Additionally, the Q-Corps would provide site supportive supervision which would allow providing on-the-spot corrective actions. It was emphasized that Q-Corps is not a stand-alone program but is integrated within the MOH system, is supervised by the MOH, and encourages partnership with local implementing partners for sustainability.

Creation of a network of testers within communities

This approach includes establishing a database of certified testers. This database would include those who have been trained and certified competent to perform a POCT test. For cascading of training, only certified testers would provide further training. This would limit suboptimal training that is often not standardized and does not provide a practical hands-on component. The network of testers could be structured along the tiered healthcare delivery system (national, regional, district, and community level). Certification of testers should be for a specified duration after which recertification should be performed.

Stepwise process for continuous improvement of HIV-related point-of-care testing

POCT is mostly used outside the traditional laboratory settings, for instance, at voluntary counseling and testing and antenatal care sites where they are used by lay counsellors, nurses, and health extension workers. These sites lack standard oversight to regularly monitor and ensure quality of testing when compared with laboratories where the WHO/Stepwise Laboratory Quality Improvement Process Towards Accreditation checklist is available for use in monitoring laboratories. This has fueled the perception of double standards that may compromise quality of POCT outside laboratory settings. The checklist would address this gap and enable a standard approach to monitoring these testing sites.

Establishing and/or engaging new partnerships

No single group can deliver or ensure quality within the health system. Over reliance on the MOHs to implement these activities can be burdensome and ineffective. New partnerships including using local implementing partners or institutions and public private partnerships to increase uptake, coverage, and quality of HIV-related POCT should be established.

The innovative approaches would need to be coordinated within the MOH structure. The MOH would need to provide strong leadership and oversight in creating an enabling environment and conditions for partnership with the private sector and local partners to use novel strategies, such as the Q-Corps, to support quality assurance programs.

Postmeeting recommendation implementation

Following the consultation, many of the meeting recommendations have been pilot tested with successful outcomes as indicated below. For instance, field implementation of the Q-Corps with emphasis on the QAC, stepwise process for improving the quality of HIV rapid testing has been successfully implemented.

Cameroon experience with implementing the quality assurance cycle and quality assurance cycle; volunteer quality corps

With direct technical assistance from CDC/PEPFAR, Cameroon successfully launched implementation of the QAC using Q-Corps, the DTS proficiency testing program, and the standardized HIV logbook in May 2014. The MOH fully endorsed and embraced the QAC and the Q-Corps initiative and provided strong leadership for its launch. Through the leadership of the MOH and PEPFAR teams in Cameroon, 31 Q-Corps staff were recruited and trained on QAC, DTS, HIV logbook, data management, biosafety, and troubleshooting approaches. PEPFAR Cameroon and the MOH engaged a local partner, Global Health System Solution, who recruited the Q-Corps staff through a competitive process. The local partner manages Q-Corps expenses on transportation, accommodations, reservations, and meals and incidentals as they conduct regularly scheduled site visits.

The Q-Corps visited more than 75 sites by August 2014 implementing QAC using DTS proficiency testing and standardized logbook. The Q-Corps also implemented the stepwise process for improving the quality of HIV-related POCT checklist. The Q-Corps appreciated the opportunity to serve and improve the quality of testing in their communities, with preliminary results that indicated that with the Q-Corps turn-around time to receive proficiency testing results from participating sites was reduced from 30 days to 5 days. Additionally, the Q-Corps provided on-the-spot corrective actions for sites they distributed proficiency testing panels. Enrolled sites have expressed satisfaction at the attention, supervision, and timely necessary corrective actions.

African Society of Laboratory Medicine WHO Tanzania meeting, June 23–25, 2014

Tanzania, ASLM, and WHO convened a meeting on June 23–25, 2014 bringing together policy makers, program managers, clinicians, scientists, local implementing partners, and agencies to discuss the draft products of the WHO/PEPFAR February 27–28, 2014 consultation in Atlanta, namely: recommendations for innovative strategies and guidance for implementing quality-assured HIV-related POCT; and a consensus policy framework document for implementing quality-assured HIV-related POCT. The two documents were presented to the larger forum at the meeting and there was broad consensus. Countries endorsed the documents with each country committed to developing an implementation plan with targets and indicators to translate the document into action (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary consultations on increased access and quality assured point-of-care testing.

| Consultation | Date | Main outcome |

| WHO/ASLM, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania meeting on improving access and increasing quality of HIV rapid testing in Africa | June 2014 | Endorsement of the quality assurance cycle by ministries of health |

| Endorsement of two draft WHO documents: strategies and guidance for implementing quality-assured HIV-related point-of-care testing; and Consensus policy framework document for implementing quality-assured HIV-related point-of-care testing | ||

| Commitment to implement innovative approaches to ensure closing of the quality assurance cycle and to improve quality of HIV rapid testing | ||

| CDC/PEPFAR/WHO Euro, Copenhagen, Denmark on HIV rapid test quality improvement initiative in Central Asia and Eastern Europe | June 2014 | Endorsement of initiative to improve quality of HIV rapid testing |

| WHO/PAHO, UNAIDS, PEPFAR, Port of Spain, Trinidad, and Tobago on access to quality HIV-related diagnostics | October 2014 | Access to quality HIV-related diagnostics as a human right entitlement |

| Endorsement of the QAC and innovative approaches to improve quality of HIV-related diagnostics | ||

| Call for creation of Caribbean technical working group to facilitate implementation of access and quality of HIV-related point-of-care testing diagnostics |

ASLM, African Society for Laboratory Medicine; CDC, Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention; PAHO, Pan American Health Organization; PEPFAR, President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief; QAC, Quality Assurance Cycle; UNAID, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV; WHO, World Health Organization.

WHO/African Society of Laboratory Medicine advocacy on innovative strategies

WHO and ASLM have taken a critical role in advocating the uptake and implementation of meeting recommendations. In addition to convening meetings to write up the policy and quality assurance documents, they have written to MOHs of African member states; for instance, the MOH of Cameroon, to encourage implementation of the QAC and innovative strategies to ensure the cycle is completed.

Expanding the innovative strategy to other President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief -supported regions

Copenhagen, Denmark June 19–21, 2014

The International Laboratory Branch of the Division of Global HIV/AIDS at CDC and WHO Europe Office held a three-day meeting from June 19–21, 2014 in Copenhagen, Denmark to engage 10 PEPFAR-supported countries from Central Asia and Eastern Europe on HIV rapid test quality improvement initiative principles and efforts, and POCT as a whole. Participants included senior program managers, laboratory experts, and policy makers; the Ukrainian Vice Minister of Health also attended the meeting. The initiative was welcomed in the region, and the Regional Director of WHO Europe expressed strong support and recommended that the planned activities be included in the WHO Global and European Regional Action Plan 2015–2020 to ensure high-quality standards and proficiency in HIV rapid testing and POCT (Table 1). For this purpose a regional TWG has been established, represented by experts from Eastern Europe and Central Asia, which will provide advice and technical guidance for developing and implementing priority activities in the area of the diagnostics access initiative and in achieving the 90 × 90 × 90 targets.

Port of Spain, Trinidad, and Tobago, October 20–23, 2014

WHO/Pan American Health Organization, UNAIDS, PEPFAR/CDC and partners convened from October 20–23, 2014 to review the quality of HIV-related POCT and care and treatment targets. Recognizing the challenge of quality HIV rapid testing and its devastating consequences to individuals, families, and communities, the participants resolved to create a Caribbean TWG to assist with increased access to quality HIV-related point-of-care diagnoses and to allocate funding to improve the quality of HIV-related POCT toward achieving the UNAIDS 90 × 90 × 90 targets. The meeting ended with a call to action and a final declaration statement ‘access to quality assured HIV-related diagnostics as a human rights entitlement of residents of the Caribbean Region’ (Table 1).

In Conclusion

Accurate and reliable results using HIV-related POCT remains a priority in healthcare programs. Consensus on strategies to improve the quality of diagnosis, and increase uptake and coverage has been well received by program implementers. The recommendations also laid the groundwork for developing key policy and quality documents for the implementation of HIV-related POCT.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Shanita Williams, Mary E. Ewing, and Theresa Nesmith for their administrative and logistic assistance in successful outcome prior and during the consultation.

Source of funding: The consultation has been supported by the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization.

Disclaimer: the findings and conclusions in this report are views of authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author contributions: P.N.F., S.O., J.N.N. wrote the paper. P.N.F., J.K., S.O., J.B.N., P.B., R.W.P., R.T., G.F., W.S., and V.H. read, revised, and approved the paper.

PARTICIPANTS LIST: Alash’le Abimiku, University of Maryland, USA; Heidi Albert, Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, South Africa; Randy Allen, Zach Katz, Jonathan Lehe, Lara Vojnov, Clinton HIV Access Initiative (CHAI), USA; Trevor Peter, CHAI, Botswana; Martin Auton, Joelle Daviaud, The Global Fund, Geneva, Switzerland; Ball Blake, National Microbiology Laboratories, Canada; Dave Barnett, United Kingdom National External Quality Assessment Service (UK NEQAS); Sergio Carmona, Lesley Scott, National Health Laboratory Services (NHLS), South Africa; Shannon Castle, Melissa Meeks, American Society for Clinical Pathology, USA; Ben Cheng, Pangea Global AIDS Foundation, USA; Kerry Dierberg, Bill Coggin, Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator, Washington DC, USA; Comstock, Gordon, Peter Smith, Jason Williams, Partnership for Supply Chain Management, USA; Elliot Cowan, Partnerships in Diagnostics, USA; Erika White Davies, Joe Fitzgibbon, Marco Schito, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, USA; Thomas Denny, Duke University, USA; Glen Fine, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, USA; Irena Prat, Nathan Ford, Willy Urassa, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; Lynee Galley, American Society for Microbiology, USA; Guy-Michel Gershey-Damet, World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa, Brazzaville, Congo; Myriam Henkens, Cara Kosack, Elsa Tran, Médecins Sans Frontières, The Netherlands; Ilesh Jani, National Health Laboratory (NHL), Mozambique; Phyllis Kanki, Harvard University, USA; Jonathan Levine, Children's Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF), USA; Peter McDermott, CIFF, UK; Charles Massambu, Ministry of Health (MOH), Tanzania; Robert Matiru, Brenda Waning, UNITAID, Geneva, Switzerland; Souleymane Mboup, Cheikh Anta Diop University (CADU), Senegal; Tsehaynesh Messele, African Society for Laboratory Medicine, Ethiopia; Ross Molinaro, Emory University, USA; Fausta Mosha, MOH, Tanzania; Tsietso Mots’oane, MOH, Lesotho; Maurine Murtagh, The Murtagh Group, LLC, US; Divya Rajaraman, Stuart Turner, Bibiana Zambrano, United Nations Children's Fund, USA; Angelii Abrol, Amitabh Adhikari, Simon Agolory, Heather Alexander, Nancy Anderson, Moses Bateganya, Suzanne Beard, Stephanie Behel, Sehin Birhanu, Deborah Birx; Debi Boeras, Naomi Bock, Melissa Briggs, Laura Broyles, Denise Casey, Joel Chehab, Tom Chiller, Ebenezer David, Margarett Davis, Anand Date, Cari Courtenay-Quirk, Karidia Diallo, Kainne Dokubo, Yen Duong, KC Edwards, Dennis Ellenberger, Steven Etheridge, Rubina Imtiaz, Nnaemeka Iriemenam, Keisha Jackson, John Kaplan, Thomas Kenyon, Luciana Kohatsu, Arielle Lasry, Philip Lederer, Stephanie Lee, Eucaris Torris Leon, Beth Luman, Elizabeth Marum, Amy Medley, Shanna Nesby, Theresa NeSmith, Shon Nguyen, Bharat Parekh, Hetal Patel, Michela Roberts, Erin Rottinghaus, Ahmed Saadani, Connie Sexton, Thomas Spira, Ritu Shrivastava, Diane Staskiewicz, Carlos Toledo, Shambavi Subbaro, Katie Tucker, David Turgeon, Maroya Walters, Larry Westerman, Audrey White, Chunfu Yang, Paul Young, Mireille Kalou, Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), Atlanta GA USA; Varough Deyde, CDC, South Africa; Michael Mwasekaga, CDC Tanzania; Clement, Zeh, CDC, Kenya.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf [Accessed July 2015] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. The Gap Report. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf [Accessed July 2015] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS. Ambitious treatment targets: Writing the final chapter of the AIDS epidemic. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2670_UNAIDS_Treatment_Targets_en.pdf [Accessed July 2015] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS. UNAIDS and partners launch initiative to improve HIV diagnostics; 2014. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2014/july/20140723dai/ [Accessed September 2015] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pai NP, Pai M. Point-of-care diagnostics for HIV and tuberculosis: landscape, pipeline, and unmet needs. Discov Med 2012; 13:35–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peeling RW, Holmes KK, Mabey D, Ronald A. Rapid tests for sexually transmitted infections (STIs): the way forward. Sex Transm Infect 2006; 82 Suppl 5:v1–v6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulinda N, Johnstone K, Newton K. Case report: HIV test misdiagnosis. Malawi Med J 2011; 23:122–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhattacharya R, Barton S, Catalan J. When good news is bad news: psychological impact of false positive diagnosis of HIV. AIDS Care 2008; 20:560–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanks L, Klarkowski D, O’Brien DP. False positive HIV diagnoses in resource limited settings: operational lessons learned for HIV programmes. PLoS One 2013; 8:e59906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klarkowski DB, Wazome JM, Lokuge KM, Shanks L, Mills CF, O’Brien DP. The evaluation of a rapid in situ HIV confirmation test in a programme with a high failure rate of the WHO HIV two-test diagnostic algorithm. PLoS One 2009; 4:e4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. WHO. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85321/1/9789241505727_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed July 2015] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO. WHO Information Note: Reminder to retest all newly diagnosed HIV-positive individuals in accordance with WHO recommendations. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/hivaids/news/news/2014/11/who-information-note-reminder-to-retest-all-newly-diagnosed-hiv-positive-individuals-in-accordance-with-who-recommendations 2014. [Accessed July 2015] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO. Global update on HIV treatment 2013: results, impact and opportunities, 2013: 126. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85326/1/9789241505734_eng.pdf [Accessed July 2015] [Google Scholar]