Abstract

Objective

Since hyperthermia selectively kills lung cancer cells, we developed a venovenous perfusion-induced systemic hyperthermia (vv-PISH) system for advanced lung cancer therapy. Our objective was to test the safety/accuracy of our vv-PISH system in five day sheep survival studies, following Good Laboratory Practice standards.

Methods

The vv-PISH system, which included a double lumen cannula (DLC, AvalonElite™); a centrifugal pump (Bio-Pump 560®); a heat exchanger (BIOtherm™); and a heater/cooler (modified Blanketrol III™), was tested in healthy adult sheep (n=5). The perfusion circuit was primed with pre-warmed Plasma-Lyte®A and de-aired. Calibrated temperature probes were placed in right/left nasopharynx, bladder, and blood in/out of animal. The DLC was inserted in jugular vein into the superior vena cava, with the tip in the inferior vena cava.

Results

Therapeutic core temperature (42-42.5°C), calculated from right/left nasopharnx and bladder temperatures, was achieved in all sheep. Heating time was 21±5 minutes. Therapeutic core temperature was maintained for 120 minutes followed by a cooling phase (35±6 min) to reach baseline temperature. All sheep recovered from anesthesia with spontaneous breathing within 4 hours. Arterial, pulmonary, and central venous pressures were stable. Transient increases in heart rate, cardiac output, and blood glucose occurred during hyperthermia but returned to normal range after vv-PISH termination. Electrolytes, complete blood counts, and metabolism enzymes were within normal to near normal range throughout the study. No significant vv-PISH-related hemolysis was observed. Neurological assessment showed normal brain function all 5 days.

Conclusion

Our vv-PISH system safely delivered the hyperthermia dose with no significant hyperthermia-related complications.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the U.S.1 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for about 85% of new lung cancer cases and is often diagnosed at an advanced stage.2 Advanced NSCLC patients have only a 9-13.5 month median survival.3-6 Moreover, chemotherapy results in only a 1.5 month improvement in survival over supportive care alone.7 Thus, a critical need for more effective lung cancer therapies exists.

Hyperthermia is a promising new therapy for advanced lung cancer because lung cancer cells are thermo-sensitive with significantly reduced heat shock protein expression.8 Hyperthermia selectively kills lung cancer cells via apoptosis8-10 and increases the cytotoxicity of chemotherapy. Moreover, hyperthermia reverses cisplatin resistance by enhancing platinum uptake and inhibiting platinum-induced DNA repair.9-13

Whole body hyperthermia for advanced cancer treatment has been proposed since the 1970’s.10,14-15 However, it has not been proven to be clinically practical for cancer treatment in terms of safety and efficiency. We developed an efficient yet safe therapeutic hyperthermia dose (42-42.5 °C for 2 hrs) for safe cancer treatment.16-18 Temperatures below this hyperthermia dose do not kill cancer cells, whereas temperatures above it will cause normal cell damage.10,13,19 Precise control of the whole body temperature to fit this narrow therapeutic hyperthermia window is very difficult. A venovenous perfusion-induced systemic hyperthermia (vv-PISH) system was developed to precisely deliver the thermal dose (42-42.5 °C for 2 hrs) for advanced lung cancer treatment. The bulky and complicated first generation vv-PISH system resulted in unwanted and worrisome clinical consequences, preventing further clinical investigation.18 For practical clinical application of hyperthermia, we recently developed a simplified vv-PISH system and management protocol.20-21 In this paper, we report the results of our preclinical Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) investigation which was designed to prove the safety and accuracy of the simplified vv-PISH system in a 5 day sheep survival study. Our results showed that an accurate dose of therapeutic hyperthermia was safely delivered to sheep with no hyperthermia-related complications.

METHODS

All animal studies were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.” All animal studies were performed in compliance with GLP standards.22

Anesthesia and Instrumentation

Adult female cross-breed sheep (32-36 kg, n=5) were intubated after anesthesia induction with ketamine (5mg/kg, i.v.) and diazepam (0.25mg/kg, i.v.), followed by 4-5% isoflurane. After intubation, anesthesia was maintained with 1-3% isoflurane through the anesthesia machine (Narkomed 2B, DRAGER, Telford, PA). Prophylactic analgesia (buprenorphine 0.005-0.020 mg/kg, s.c.) and antibiotic (enrofloxacin 7.5 mg/kg, s.c.) were administered. The sheep were ventilated at 8-10 ml/kg tidal volumes with 12-20 respirations per minute to maintain 30-35 mm Hg ETCO2.

A Gelli-Roll® warming gel pad (Cincinnati Subzero, Cincinnati, OH) was placed under the sheep and a Warm-Air® convective warming blanket (Cincinnati Subzero, Cincinnati, OH) was placed over the sheep before instrumentation. These external heating devices were set at 38°C to maintain baseline core temperature and were set at 42°C during the heating and therapeutic phases to augment hyperthermia. Two 16 G catheters (Becton Dickinson, Sandy UT) were placed into the femoral artery and vein for blood sampling/pressure monitoring and fluid administration, respectively. A Swan-Ganz catheter (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine CA) was placed percutaneously through the left jugular vein to the pulmonary artery (PA) for measurement of cardiac output (CO), PA pressure (PAP), central venous pressure (CVP), and PA blood temperature. The catheters were connected to transducers (Edwards Lifesciences Irvine, CA) for monitoring arterial blood pressure (ABP), CVP, and PAP via a Phillips MP-50 monitor (Phillips, Boeblingen, Germany). Temperature probes were placed in the bladder (Foley catheter), right/left nasopharynx, and blood in/out of animal. To avoid isoflurane-induced vasodilation and consequent lower blood pressure during hyperthermia, the dosage of isoflurane was reduced with addition of continuous propofol (0.4 mg/kg/min) iv infusion and bolus vecuronium iv injection (loading dose: 0.025-0.4 mg/kg, subsequent doses: 0.007-0.1 mg/kg) to maintain operative anesthesia.

Installation and Maintenance of VV-PISH

The vv-PISH system consisted of: 1) double lumen cannula (DLC, Avalon Elite™, Rancho Dominguez, CA)23, 2) centrifugal pump (Bio-Pump 560®, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN), 3) heat exchanger (BIOtherm™, Medtronic Perfusion Systems, Brooklyn Park, MN), and 4) heater/cooler (modified Blanketrol III™, Cincinnati Subzero, Cincinnati, OH). The vv-PISH blood circuit was flushed with CO2 and then primed with pre-heated (up to 46°C) priming solution (Plasma- Lyte®A), which circulated with the heater to maintain the temperature.21

Systemic anticoagulation was initiated with a heparin bolus (150 U/kg, i.v.) and maintained at an activated clotting time of 180-250 sec. The DLC was inserted in the right jugular vein into the superior vena cava (SVC), traversing the right atrium (RA), with the tip positioned in the inferior vena cava (IVC). The DLC was connected to the primed vv-PISH circuit. When the pump was started, the venous blood was drained from the DLC drainage lumens (IVC/SVC) and sent to the heat exchanger for heating. The heated blood was pumped back through the DLC infusion lumen into RA-pulmonary circulation. The circuit blood flow was 1.5-1.6 L/min to heat the sheep, targeting a 42 °C core temperature. This 42 °C core temperature was maintained for 2 hrs for the therapeutic window. After 2 hrs of hyperthermia, the cooling phase was started by circulating cool water through the heat exchanger until the core temperature returned to 39 °C.

Data Acquisition During VV-PISH

The data acquisition system used in this study was the cDAQ9172 (National Instruments, Austin, TX) with temperature, pressure, and a flow modules. The temperature module was connected to temperature probes placed in the bladder, right/left nasopharynx, and blood in/out tubing for constant temperature measurement. The core temperature was defined as the average of the bladder, right and left nasopharynx temperatures. The pressure module was connected to the pressure sensors for ABP, CVP, and PAP monitoring. The flow module was connected to a flow meter (T110, Transonic Systems Inc., Ithaca NY) for circuit blood flow monitoring. Data acquisition software (Labview 8.6, National Instruments, Austin, TX) was used to record temperature, blood pressure, and pump flow rates simultaneously at 5 Hz.

Animal Monitoring and Blood Analysis During VV-PISH

Blood chemistries, complete blood counts, free hemoglobin, CO, and PA wedge pressure (PAWP) were measured at the following time-points: 1) baseline, 2) therapy start, 3) therapy middle (1 hour of 42 °C hyperthermia), 4) therapy end (2 hours of 42 °C hyperthermia), and 5) cool 39 (when 39 °C was achieved). Arterial blood gases and electrolytes were measured every 15 minutes using a blood gas analyzer (Cobas b221, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Hemodynamics were continuously monitored, and urine output was measured hourly. Continuous intravenous infusion of lactated Ringer’s (744±205 ml/hr) was used to maintain blood volume for stable hemodynamics. Supplemental calcium chloride (100 mg/ml, i.v.) or potassium chloride (10-80 mEq, i.v.) was used as needed to correct hypocalcemia or hypokalemia, respectively. A furosemide bolus (10-50 mg, i.v.) was given if hourly urine output was less than 50 ml.

Five Day Post-VV-PISH Animal Monitoring and Blood Analysis

After completion of the hyperthermia experiment, the sheep was taken off perfusion and the DLC decannulated. The femoral arterial and Swan-Ganz catheters were left in place throughout the 5 day study for blood pressure monitoring, blood sampling, and fluid administration. The sheep was moved into a metabolic cage and transferred to the ICU. The sheep was weaned from mechanical ventilation/anesthesia. Once spontaneous breathing maintained normal PaCO2 and PaO2 levels, the endotracheal tube was removed. Thereafter, the sheep had free access to food and water throughout the study. For the first 2 days, buprenorphine (0.005–0.02 mg/kg, s.c.) and enrofloxacin (7.5 mg/kg, s.c) were given.

Hemodynamics were continuously monitored and recorded every 6 hours. Blood gases/electrolytes were measured every 6 hrs while complete blood counts/blood chemistries were measured every 24 hrs. Neurological assessments were performed every 24 hrs. These assessments were based on the Glasgow Coma scale (0-15) which was modified for sheep to assess cranial nerve function. A score of 15 on this modified Glasgow Coma scale was considered normal.

Animal Euthanasia and Necropsy

After successful completion of the five day post-hyperthermia survival period, all sheep were euthanized with Beuthanasia-D (1 mL/10 lb body weight, Schering-Plough, Union, NJ) and subjected to a full necropsy. The brain, lungs, heart, liver, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, spleen, adrenals, and bladder were grossly examined and samples of these tissues were preserved in 10% buffered formalin. The tissue sections were paraffin-embedded and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Slides were examined by a veterinary histopathology lab (Antech Diagnostics, Louisville, KY).

Data Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Differences between the baseline and subsequent time-points were evaluated using analysis of variance with a Dunnett post test.

RESULTS

All five sheep survived the hyperthermia experiment, achieving 2 hrs of 42.0±0.2 °C therapeutic hyperthermia. All sheep recovered from the vv-PISH procedure, were awake with spontaneous breathing within 4 hours, and survived the full 5 day post-hyperthermia study period.

VV-PISH Circuit Efficiency

The baseline core temperature was 38.1±0.3 °C. During the heating phase, a 21±5 min heating time was needed to achieve a 42°C core temperature. Average warming rate was 1°C per 5.22±0.78 min. After the 2 hrs of 42°C hyperthermia were completed, 35±6 min was taken to cool the sheep to 39°C. Average cooling rate was 1°C per 12.8±1.2 min.

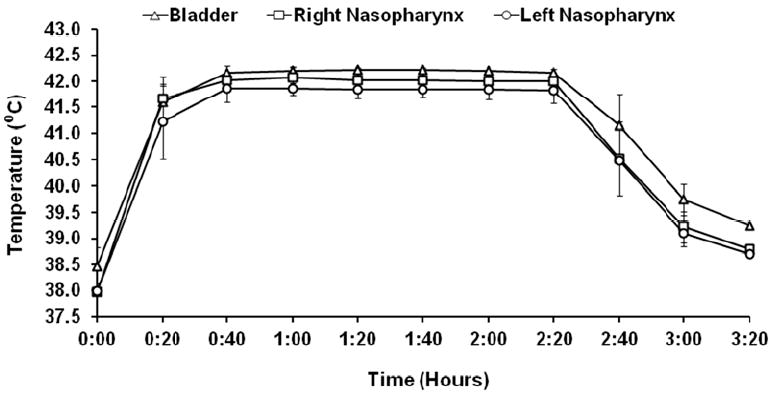

Precise Temperature Control of VV-PISH

The sheep temperature did not exceed 42.5°C at any measured site throughout the hyperthermia experiment (Figure 1A). Moreover, the core temperature (41.8-42.2°C) varied by only 0.26±0.1 °C during the 2 hr therapeutic hyperthermia phase (Figure 1B). The circuit blood infusion temperature reached a maximum of 42.3 ± 0.30 °C during the heating phase and a minimum of 36.9± 0.18 °C during the cooling phase (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Hyperthermia Temperature Profile. 1A: Bladder, right/left nasopharynx temperatures measured during heating, therapeutic, and cooling phases. Homogeneous heat distribution was observed with no temperatures above 42.5°C. 1B: Relationship between core temperature and circuit infusion (blood in)/drainage (blood out) temperatures. Maximal circuit blood infusion temperature was 42.3°C.

Hemodynamics

Mean arterial pressure (MAP), CVP, mean PAP (mPAP), and PAWP were stable and in physiological range throughout the vv-PISH experiment and the 5 day post-hyperthermia period (Table 1). Heart rate and cardiac output were significantly increased during the hyperthermia experiment, returning to baseline values by post-hyperthermia day 1 and remaining stable throughout the rest of the study.

Table 1.

Hemodynamics

| Baseline | Heat 39 | Heat 40 | Heat 41 | Therapy Start | Therapy Middle | Therapy End | Cool 41 | Cool 40 | Cool 39 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP | 106±11 | 98±17 | 108±10 | 103±9 | 99±9 | 102±5 | 101±5 | 105±9 | 104±8 | 101±13 | 98±9 | 90±3 | 95±5 | 98±9 | 93±3 |

| HR | 110±16 | 131±1 4 | 150±32 | 152±26 * | 153±18 * | 159±27 * | 156±21 * | 154±23 * | 160±24 * | 161±37 * | 102±6 | 103±14 | 104±9 | 104±9 | 112±26 |

| mPAP | 14±5 | 15±4 | 15±3 | 15±4 | 15±4 | 14±2 | 16±3 | 16±2 | 16±2 | 16±1 | 14±3 | 15±3 | 15±3 | 14±2 | 15±3 |

| CVP | 3±2.2 | 4±3.8 | 4±4.5 | 4±4.9 | 4±5.1 | 5±3.6 | 6±2.9 | 6±2.7 | 7±3.1 | 7±3.1 | 0±2.6 | 1±3.7 | 1±2.7 | 0±1.0 | 1±1.2 |

| CO | 4.5±1.7 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 8.6±3.3 * | 10.9±4.3 * | 10.7±2.7 * | N.D. | N.D. | 11.5±2.3 * | 8.2±0.8 | 7.4±1.2 | 7.9±1.1 | 6.9±1.1 | 7.2±1.3 |

| PAWP | 6±3.0 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 5±2.5 | 5±2.3 | 6±3.1 | N.D. | N.D. | 5±1.1 | 7±1.5 | 7±2.4 | 7±1.5 | 7±2.3 | 9±2.3 |

Hemodynamics were recorded at Baseline, Heat 39 (core temperature 39° during heating), Heat 40 (core temperature 40° during heating), Heat 41 (core temperature 41° during heating),Therapy Start (when 42°C target was met),Therapy Middle (1 hr at 42°C), Therapy End (2 hrs at 42°C), Cool 41 (core temperature 41° during cooling), Cool 40 (core temperature 40° during cooling), Cool 39 (core temperature 40° during cooling), Day 1 (post-hyperthermia day 1), Day 2 (post-hyperthermia day 2), Day 3 (post-hyperthermia day 3), Day 4 (post-hyperthermia day 4), and Day 5 (post-hyperthermia day 5).

MAP=mean arterial pressure, HR=heart rate, mPAP=mean pulmonary artery pressure, CVP=central venous pressure, CO=cardiac output, PAWP=pulmonary artery wedge pressure, and N.D.=not determined. N=5 sheep,

=p<0.05 vs baseline.

Fluid and Electrolyte Balance

During the hyperthermia experiment, lactated Ringer’s infusion (3,070±683 mL) was used to maintain blood volume for stable hemodynamics. Urine output was 292±101 mL/hr during vv-PISH. The average daily urine output during the 5 day post-hyperthermia study period was 1454±345 mL (72±13 mL/hr). Blood sodium levels were within normal physiological range throughout vv-PISH and the 5 day post-hyperthermia monitoring period (Table 2). Blood potassium levels were in normal range during the heating and therapeutic phases, but were lower than physiological range during the cooling phase. Continuous intravenous KCl supplementation was given during the first 24 hours after vv-PISH, and blood potassium returned to normal levels by 12 hrs post-vv-PISH. Blood calcium and chloride were in physiological range throughout the hyperthermia experiment. Bicarbonate and pH were stable during vv-PISH. The pH levels were slightly elevated from post-vv PISH day 1 to day 5 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Electrolytes

| Baseline | Therapy Start | Therapy Middle | Therapy End | Cool 41 | Cool 40 | Cool 39 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ | 141±1 | 139±2 | 137±2 * | 136±1 * | 136±1 * | 136±2 * | 135±2 * | 147±2 * | 147±1 * | 145±1 * | 145±2 * | 146±2 * |

| K+ | 3.52±0.43 | 4.01±0.38 | 3.93±0.42 | 3.74±0.20 | 3.33±0.27 | 3.13±0.17 | 3.21±0.30 | 3.96±0.27 | 4.04±0.13 | 3.87±0.2 | 3.92±0.27 | 3.95±0.37 |

| Ca2+ | 1.15±0.07 | 1.09±0.02 | 1.11±0.04 | 1.18±0.14 | 1.12±0.06 | 1.09±0.06 | 1.15±0.08 | 1.22±0.03 | 1.25±0.07 | 1.22±0.10 | 1.26±0.05 | 1.26±0.04 |

| Cl- | 102±2 | 103±1 | 100±2 | 99±1 | 101±1 | 101±2 | 100±2 | 110±3 * | 104±2 | 106±5 | 104±2 | 105±2 |

| HCO3- | 27.9±0.7 | 26.4±1.2 | 26.9±0.8 | 27.0±0.5 | 25.6±0.7 | 25.1±0.9 | 25.9±1.4 | 21.8±2.0 * | 27.4±2.1 | 25.4±4.0 | 24.5±1.7 * | 24.3±2.3 * |

| pH | 7.41±0.07 | 7.39±0.03 | 7.40±0.03 | 7.41±0.03 | 7.42±0.01 | 7.41±0.02 | 7.41±0.02 | 7.46±0.04 | 7.48±0.02 * | 7.48±0.01 * | 7.51±0.02 * | 7.49±0.01 * |

Arterial blood electrolytes were measured at Baseline, Therapy Start (when 42°C target was met),Therapy Middle (1 hr at 42°C), Therapy End (2 hrs at 42°C), Cool 41 (core temperature 41° during cooling), Cool 40 (core temperature 40° during cooling), Cool 39 (core temperature 40° during cooling), Day 1 (post-hyperthermia day 1), Day 2 (post-hyperthermia day 2), Day 3 (post-hyperthermia day 3), Day 4 (post-hyperthermia day 4), and Day 5 (post-hyperthermia day 5).

Na+=sodium, K+=potassium, Ca2+=calcium, Cl-=chloride, and HCO3-=bicarbonate. N= 5 sheep,

= p<0.05 vs baseline.

Hematology

Free hemoglobin levels were significantly increased after instrumentation before starting vv-PISH (Baseline, Table 3). Free hemoglobin levels gradually decreased, reaching 7±3 by vv-PISH termination. During the post-hyperthermia period, free hemoglobin levels were 3 mg/dl (Table 3). Hematocrit, hemoglobin, and red blood cell counts were unchanged during vv-PISH and were within physiological range during the post-hyperthermia study period (Table 4).

Table 3.

Free Hemoglobin

| Sheep | Pre surgery | Baseline | Therapy Start | Therapy Middle | Therapy End | Cool 39 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 17 | INT | INT | INT | INT | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | 7 | 20 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 3 | 4 | 25 | 13 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 7 | 43 | 20 | 13 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 5 | 7 | 43 | 18 | 16 | 13 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Mean | 6±1.3 | 30±13 * | 15±5 | 10±6 | 8±4 | 7±3 | 3±0.4 | 3±0.5 | 3±0.0 | 3±0.0 | 3±0.0 |

Free hemoglobin levels were measured at Pre Surgery (before surgery day), Baseline (after instrumentation but before vv-PISH start), Therapy Start (when 42°C target was met), Therapy Middle (1 hr at 42°C), Therapy End (2 hrs at 42°C), Cool 39 (when 39° baseline temperature was restored), Day 1 (post-hyperthermia day 1), Day 2 (post-hyperthermia day 2), Day 3 (post-hyperthermia day 3), Day 4 (post-hyperthermia day 4), and Day 5 (post-hyperthermia day 5).

INT=interference due to severe lipemia in blood sample.

=p<0.05 vs pre surgery.

Table 4.

Hematology and Blood Chemistry

| Parameter | Baseline | Therapy Start | Therapy Middle | Therapy End | Cool 39 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematocrit (%) | 26±1 | 27±0.4 | 27±0.7 | 26±1.1 | 25±2 | 30±1* | 30±3* | 27±2 | 28±1 | 26±3 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.1±0.5 | 8.9±0.5 | 9.0±0.3 | 8.7±0.5 | 8.5±0.7 | 10.4±0.6 * | 10.5±1 * | 9.7±0.8 | 9.9±0.4 | 9.4±0.7 |

| RBC (x 106/μl) | 9.8±0.7 | 9.3±0.6 | 9.3±0.6 | 8.9±0.6 | 8.6±0.8 | 11.2±0.9 | 11.3±1.4 | 10.3±1 | 10.6±0.9 | 10.0±0.9 |

| WBC (x 103/μl) | 5.5±1.9 | 7.1±2.2 | 7.5±2.4 | 6.6±2.3 | 6.1±2.7 | 12.0±3.7 * | 10.3±2.7 * | 8.4±1.6 | 7.7±2.1 | 6.9±1.2 |

| Platelets (x 103/μl) | 527±59 | 571±40 | 588±8 | 546±42 | 496±54 | 335±70 * | 363±47 * | 393±67 * | 481±102 | 462±97 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 75±17 | 101±4* | 111±17* | 140±21* | 147±19* | 79±8 | 82±11 | 82±5 | 84±16 | 89±6 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 158±40 | 168±36 | 166±36 | 161±31 | 157±32 | 162±35 | 156±54 | 130±29 | 118±19 | 121±26 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 12±4 | 11±4 | 11±4 | 10±3 | 11±4 | 70±33* | 61±26* | 46±20* | 32±15 | 31±13 |

| AST (IU/L) | 71±9 | 63±5 | 67±5 | 68±4 | 71±7 | 377±127 | 301±72* | 205±47* | 148±33 | 142±19 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 18±3 | 17±2 | 18±3 | 17±3 | 17±3 | 7±2* | 10±2* | 10±2* | 11±3* | 13±3* |

| Creatine (mg/dL) | 0.6±0.1 | 0.6±0.1 | 0.6±0.1 | 0.7±0.1 | 0.7±0.1 | 0.6±0.1 | 0.6±0.1 | 0.6±0.1 | 0.6±0.1 | 0.6±0.1 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.8±0.2 | 2.4±0.1* | 2.4±0.1* | 2.3±0.1* | 2.2±0.2* | 3.0±0.1 | 2.9±0.1 | 2.8±0.2 | 3.0±0.2 | 2.9±0.2 |

| Total Protein (g/dL) | 5.3±0.5 | 4.4±0.2* | 4.2±0.2* | 4.0±0.2* | 3.9±0.3* | 5.5±0.2 | 5.5±0.2 | 5.4±0.1 | 5.7±0.2 | 5.5±0.2 |

| CPK (IU/L) | 213±16 | 266±27 | 336±29 | 427±83 | 572±184 | 1118±1056 | 458±317 | 196±80 | 168±93 | 153±83 |

Complete blood counts were measured at Baseline, Therapy Start (when 42°C target was met), Therapy Middle (1 hr at 42°C), Therapy End (2 hrs at 42°C), Cool 39 (when 39° baseline temperature was restored), Day 1 (post-hyperthermia day 1), Day 2 (post-hyperthermia day 2), Day 3 (post-hyperthermia day 3), Day 4 (post-hyperthermia day 4), and Day 5 (post-hyperthermia day 5).

RBC=red blood cells, WBC=white blood cells, ALP=alkaline phosphatase, ALT=alanine aminotransferase, AST=aspartate aminotransferase, BUN=blood urea nitrogen, and CPK=creatinine phosphokinase. N= 5 sheep,

=p<0.05 vs baseline.

White blood cell counts were stable during vv-PISH application, but were significantly increased one and two days after hyperthermia administration, returning to baseline levels by day 3 (Table 4). The percentage of granulocytes, lymphocytes, and monocytes were unchanged (data not shown). Platelet counts were significantly reduced at post-hyperthermia days 1-3 but were still within normal range.

Blood Comprehensive Metabolism

Blood glucose was elevated slightly above physiological level during the therapeutic and cooling phases but returned to baseline values by post-hyperthermia day 1 (Table 4). Throughout the study, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels were stable. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aminotransferase (AST) levels were unchanged during vv-PISH, but ALT and AST levels were significantly elevated on post-hyperthermia days 1-3, returning to normal range by day 4. Throughout the study, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine were in normal range (Table 4). Albumin and total protein were slightly below the normal range during the therapeutic and cooling phases, but returned to baseline values by post-hyperthermia day 1. Creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) levels were not significantly altered during vv-PISH application (Table 4). However, CPK levels were elevated one and two days after hyperthermia, returning to baseline values by post-hyperthermia day 3.

Neurological Assessment

All five sheep scored 15 on the Glasgow Coma scale throughout the post-hyperthermia period, indicating normal cranial nerve function. The sheep also exhibited normal behavior in terms of eating, standing, and response to humans.

Histology

No abnormalities were observed in the brain, heart, and adrenal glands of all five sheep. The lungs in all sheep had areas of atelectasis which were likely due to previous lung infection or anesthetic procedure. Mild diffuse hepatocellular cytoplasmic clumping and coagulation were also found in the livers of all five sheep, an effect likely due to mild hypoxia. Two sheep had one kidney exhibiting signs of ischemic injury whereas the other kidney was normal. The stomach in three sheep showed signs of gastritis. Inflammation with coexisting parasitism was present in the intestinal tract of all five sheep. Spleen congestion was also found in four sheep.

DISCUSSION

In this five day, GLP compliant sheep survival study, our simplified vv-PISH system safely delivered an accurate therapeutic hyperthermia dose with no evidence of immediate or long-term hyperthermia-related complications. With our vv-PISH system, fast heating with stable ABP/PAP/CVP, normal to near normal levels of blood electrolytes/metabolic enzymes/ hematological parameters, and negligible vv-PISH-related hemolysis was achieved with rapid anesthesia recovery.

The vv-PISH system utilizes an extracorporeal pump-heat exchanger circuit to withdraw a portion of venous blood for heating, which is then pumped back into the pulmonary system where it is well mixed with unheated venous blood. This heated blood from the pulmonary circulation is then evenly distributed to the systemic circulation by the left heart to achieve homogenous heat delivery.16,18,21 With the vv-PISH system, hyperthermia can be delivered to all sites affected by metastatic cancer including the visceral organs and previously privileged areas for cancer metastasis such as the bone marrow, brain, vertebral column, and mediastinum.16,18 Another advantage of the vv-PISH system is the shorter heat time needed to reach the target temperature which enhances cancer cell kill by limiting the recruitment of thermo-protective mechanisms.8,12,18,21,24 Moreover, rapid heating expedites apoptosis to more efficiently kill cancer cells.8,24 Thus, the vv-PISH system has significant advantages which will likely enhance the efficacy of hyperthermia.

A first generation vv-PISH circuit was developed by our group and tested in 10 advanced NSCLC patients in a phase I safety trial with promising results.16-18 A DLC-based extracorporeal circuit for systemic hyperthermia has also been developed by an Austrian group.25 While these systemic hyperthermia systems functioned adequately in their respective clinical trials, there were several critical issues requiring resolution. First, unstable hemodynamics in all the patients required norepinephrine, large volume fluid resuscitation (6 L), and vigorous diuresis. 18,25 Second, post-hyperthermia somnolence existed for up to 48 hours, and extubation was delayed up to 36 hrs due to pulmonary edema. 17-18 Third, moderate hemolysis and thrombocytopenia were observed.17,25 Fourth, the heating phase was too long (>45 minutes), allowing time for the cancer cells to develop thermotolerance.17-18,25

To address these issues, we simplified the vv-PISH circuit and established anesthesia/circuit management protocols to prevent arterial hypotension and pulmonary hypertension.20,21 In the current study, this next generation vv-PISH circuit successfully delivered an accurate hyperthermia dose. Hemodynamics were stable with no need for vasopressors or large fluid volumes. All sheep quickly recovered from anesthesia within 4 hours of vv-PISH termination. Neurological assessments were normal in all sheep throughout the post-hyperthermia study period, indicating the absence of brain injury. There was no vv-PISH circuit-related hemolysis as indicated by free hemoglobin levels < 20 during and after vv-PISH use. Free hemoglobin levels were elevated after instrumentation but before vv-PISH circuit hook-up, an effect most likely due to cannulation-induced hemolysis. In the current study, thrombocytopenia was not observed. With our vv-PISH circuit, fast heating while maintaining hemodynamic stability was possible, resulting in a much shorter heating time (21±5 minutes) to reach the 42°C core temperature. This is an important finding since hyperthermia induction must be rapid enough to limit thermotolerance but slow enough to maintain patient stability.26

In this five day sheep survival study, there were no severe hyperthermia-related complications, indicating the safety of our vv-PISH system. Slight elevations in liver enzymes were detected 1-3 days after hyperthermia treatment, but their return to normal range suggests the absence of significant liver injury. Two sheep had an ischemic injury to one of their kidneys. Given the normal renal performance during the study, and only one kidney being involved, it is unlikely to be related to the systemic hyperthermia treatment. Nevertheless, renal and hepatic function will be closely monitored during future patient hyperthermia treatments. CPK levels were elevated five-fold one day after hyperthermia administration, but returned to normal range by day 3. A 39-fold increase in CPK levels was also observed in the previous vv-PISH clinical trial, and the clinical study by the Austrian group also found elevations in this enzyme.17,25 Since the release of creatinine phosphokinase from skeletal muscle occurs during a malignant hyperthermia episode,27-28 the increase in creatinine phosphokinase appears to be a normal physiological response to hyperthermia.

CONCLUSION

In this preclinical GLP study, our vv-PISH system safely and reliably delivered the therapeutic hyperthermia dose with no hyperthermia-related complications. We have planned the following three steps toward clinical application of vv-PISH: 1) A FDA investigational device exemption for human trial (in process), 2) an IRB-approved clinical trial to prove the safety of vv-PISH in humans, and 3) controlled clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of vv-PISH in lung cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the technical assistance of L. Ryan Sumpter and Xiaoqin Zhou as well as the assistance of the perfusionist, Bob Jubak.

Funding Support: R42CA120616 NIH Phase II STTR grant and Johnston-Wright Endowment, University of Kentucky Department of Surgery

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stinchcombe TE, Socinski MA. Current treatments for advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:233–41. doi: 10.1513/pats.200809-110LC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scagliotti GV, Krzakowski M, Szczesna A, Strausz J, Makhson A, Reck M, et al. Sunitinib plus erlotinib versus placebo plus erlotinib in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2070–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gridelli C, Ciardiello F, Gallo C, Feld R, Butts C, Gebbia V, et al. First-line erlotinib followed by second-line cisplatin-gemcitabine chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the TORCH randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3002–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynch TJ, Bondarenko I, Luft A, Serwatowski P, Barlesi F, Chacko R, et al. Ipilimumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line treatment in stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomized, doubleblind, multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2046–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scagliotti GV, Vynnychenko I, Park K, Ichinose Y, Kubota K, Blackhall F, et al. International, randomized, placebocontrolled, double-blind phase III study of motesanib plus carboplatin/paclitaxel in patients with advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: MONET1. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2829–36. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.4987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chemotherapy in Addition to Supportive Care Improves Survival in Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data From 16 Randomized Controlled Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4617–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vertrees RA, Zwischenberger JB, Boor PJ, Pencil SD. Oncogenic ras results in increased cell kill due to defective thermoprotection in lung cancer cells. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:1675–80. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roti Roti JL. Cellular responses to hyperthermia (40–46°C): Cell killing and molecular events. Int J Hyperthermia. 2008;24:3–15. doi: 10.1080/02656730701769841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickson JA, Calderwood SK. Temperature range and selective sensitivity of tumors to hyperthermia: a critical review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1980;335:180–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb50749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vertrees RADG, Popov VL, Coscio AM, Goodwin TJ, Logrono R, Zwischenberger JB, Boor PJ. Synergistic interaction of hyperthermia and gemcitabine in lung cancer. Cancer Biol & Ther. 2005;4:1144–53. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.10.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kampinga HH. Cell biological effects of hyperthermia alone or combined with radiation or drugs: A short introduction to newcomers in the field. Int J Hyperthermia. 2006;22:191–96. doi: 10.1080/02656730500532028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Issels RD. Hyperthermia adds to chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2546–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pettigrew RT, Galt JM, Ludgate CM, Smith AN. Clinical effects of whole-body hyperthermia in adnanced malignancy. Br Med J. 1974;4(5946):679–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5946.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickson JA. Hyperthermia in the treatment of cancer. Lancet. 1979;1:202–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90594-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vertrees RA, Bidani A, Deyo DJ, Tao W, Zwischenberger JB. Venovenous perfusion-induced systemic hyperthermia: hemodynamics, blood flow, and thermal gradients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:644–52. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01381-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zwischenberger JB, Vertrees RA, Woodson LC, Bedell EA, Alpard SK, McQuitty CK, et al. Percutaneous venovenous perfusion-induced systemic hyperthermia for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: initial clinical experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:234–42. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zwischenberger JB, Vertrees RA, Bedell EA, McQuitty CK, Chernin JM, Woodson LC. Percutaneous venovenous Perfusion-Induced systemic hyperthermia for lung cancer: a phase I safety study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1916–25. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.10.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumi N, Matsumoto K, Mishima N, Moriyama E, Furuta T, Nishimoto A, et al. Thermal damage threshold of brain tissue--histological study of heated normal monkey brains. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1994;34:209–15. doi: 10.2176/nmc.34.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballard-Croft C, Wang D, Jones C, Sumpter LR, Zhou X, Thomas J, et al. Physiologic response to a simplified venovenous perfusion-induced systemic hyperthermia system. ASAIO J. 2012;58:601–6. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e318271badb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballard-Croft CWD, Jones C, Wang J, Pollock R, Topaz S, Zwischenberger JB. Resolution of Pulmonary Hypertension Complication During Veno-Venous Perfusion-Induced Systemic Hyperthermia Application. ASAIO J. 2013;59:390–396. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e318291d0a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanarek A. Good Laboratory Practice. 3. New York, NY: D&MD Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang D, Zhou X, Liu X, Sidor B, Lynch J, Zwischenberger JB. Wang-Zwische Double Lumen Cannula-Toward a Percutaneous and Ambulatory Paracorporeal Artificial Lung. ASAIO J. 2008;54:606–11. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e31818c69ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herman TS, Gerner EW, Magun BE, Stickney D, Sweets CC, White DM. Rate of Heating as a Determinant of Hyperthermic Cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 1981;41:3519–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Locker GJ, Fuchs EM, Worel N, Bojic A, Heinrich G, Brodowicz T, et al. Whole body hyperthermia by extracorporeal circulation in spontaneously breathing sarcoma patients: hemodynamics and oxygen metabolism. Int J Artif Organs. 2011;34:1085–94. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herman TS, Zukoski CS, Anderson RM. Review of the current status of whole-body hyperthermia administered by water circulation techniques. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1982;61:365–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antognini JF. Creatine kinase alterations after acute malignant hyperthermia episodes and common surgical procedures. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:1039–42. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199511000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amaranath L, Lavin TJ, Trusso RA, Boutros AR. Evaluation of creatinine phosphokinase screening as a predictor of malignant hyperthermia. A prospective study. Br J Anaesth. 1983;55:531–3. doi: 10.1093/bja/55.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]