Abstract

Genetic differences between Arabidopsis thaliana accessions underlie the plant’s extensive phenotypic variation, and until now these have been interpreted largely in the context of the annotated reference accession Col-0. Here we report the sequencing, assembly and annotation of the genomes of 18 natural A. thaliana accessions, and their transcriptomes. When assessed on the basis of the reference annotation, one-third of protein-coding genes are predicted to be disrupted in at least one accession. However, re-annotation of each genome revealed that alternative gene models often restore coding potential. Gene expression in seedlings differed for nearly half of expressed genes and was frequently associated with cis variants within 5 kilobases, as were intron retention alternative splicing events. Sequence and expression variation is most pronounced in genes that respond to the biotic environment. Our data further promote evolutionary and functional studies in A. thaliana, especially the MAGIC genetic reference population descended from these accessions.

Interpreting the consequences of genetic variation has typically relied on a reference sequence, relative to which genes and variants are annotated. However, this may cause bias, because genes may be inactive in the reference but expressed in the population1, suggesting that sequencing and re-annotating individual genomes is necessary. Advances in sequencing2 make this tractable for Arabidopsis thaliana3–5, whose natural accessions (strains) are typically homozygous. Relative to the 119-megabase (Mb) high-quality reference sequence from Col-0 (ref. 6), diverse accessions harbour a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) about every 200 base pairs (bp) (ref. 3), and indel variation is pervasive3,7,8. Characterizing this variation is crucial for dissecting the genetic architecture of traits by quantitative trait locus mapping in recombinant inbred lines (see, for example, ref. 9) or genome-wide association in natural accessions10.

Here we have sequenced and accurately assembled the single-copy genomes of 18 accessions that, with Col-0, are the parents of more than 700 Multiparent Advanced Generation Inter-Cross (MAGIC) lines9, similar to the maize Nested Association Mapping (NAM)11 population and the murine Collaborative Cross12. These accessions comprise a geographically and phenotypically diverse sample across the species9. Using the genomes, seedling transcriptomes and computational gene predictions we have characterized the ancestry, polymorphism, gene content and expression profile of the accessions. We show that the functional consequences of polymorphisms are often difficult to interpret in the absence of gene re-annotation and full sequence data. The assembled genomes also contribute to the A. thaliana 1001 Genomes Project3–5,13.

Genome sequencing, assembly and variants

We assembled the 18 genomes so that single-copy loci would be contiguous, with less than one assembly error per gene, and therefore suitable for annotation. Accessions were sequenced with Illumina paired-end reads2 (Supplementary Table 1), generally with two libraries with 200-bp and 400-bp inserts and reads of 36 and 51 bp, respectively, to between 27-fold and 60-fold coverage. Each genome was assembled by using five cycles of iterative read mapping14 combined with de novo assembly15 (Supplementary Information sections 2 and 3, and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). We aligned reads to the final assemblies to detect polymorphic regions8 lacking read coverage (2.1–3.7 Mb per accession; Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2). At unique loci, polymorphic regions probably reflect complex polymorphisms3,8. The average N50 length (the contig size such that 50% of the entire assembly is contained in contigs equal to or longer than this value) of contiguous read coverage between polymorphic regions was 80.8 kb (Supplementary Table 4).

To report complex alleles consistently, we defined all variants against the multiple alignment consensus of Col-0 and the assembled genomes. For each accession there were 497,668–789,187 single-base differences from Col-0, and about 45,000 ambiguous nucleotides (Supplementary Table 5). The latter may reflect heterozygosity (particularly in Po-0; Supplementary Figs 5–7) or copy-number variants, and they were largely in transposable elements and repeats covering 21.9% of the genome (Supplementary Information section 5.1, and Supplementary Figs 8 and 9). Of 3.07 million SNPs, 45.2% were private to single accessions.

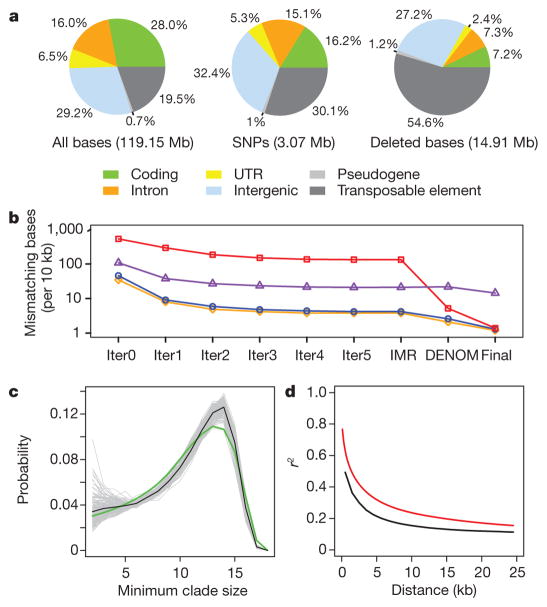

We identified 1.20 million indels, and 104,090 imbalanced substitutions, in which a sequence in Col-0 was replaced by a different sequence (Supplementary Tables 3 and 7). Although 57.5% of indels or imbalanced substitutions were shorter than 6 bp, 1.9% were longer than 100 bp, and overall 14.9 Mb of Col-0 sequence was absent in one or more accessions (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 8). The assemblies were about 1.6% and about 4.3% shorter than the reference (including and excluding polymorphic regions, respectively), probably reflecting limitations in detecting long insertions. Although sequence differences were enriched in transposable-element and intergenic regions, about 17% of bases deleted in one or more accessions were annotated as genic in Col-0 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 8). The density of sequence differences is greater than between classical inbred strains of mice16, but less than between lines of maize17.

Figure 1. Assembly and variation of 18 genomes of A. thaliana.

a, Classification of sequence, SNPs and indels based on the Col-0 genome. b, Assembly accuracy (y axis; base substitution errors per 10 kb) measured relative to four validation data sets at each of eight stages in the IMR/DENOM assembly pipeline (x axis). Bur-0 survey (blue line): 1,442 survey sequences (about 417 bp each) in predominantly genic regions19; Bur-0 divergent (red line): 188 sequences (each about 254 bp) highly divergent from Col-0 (ref. 3); Ler-0 nonrepetitive (orange line): a predominantly single-copy 175-kb Ler-0 sequence on chromosome 5; Ler-0 repetitive (purple line): a highly repetitive 339-kb Ler-0 locus on chromosome 3 (ref. 18; Supplementary Information section 4). Iter, iteration. c, Genome-wide distribution of the minimum clade size for all pairs of accessions (excluding Po-0). Each pair is represented by a grey line, the mean over all pairs by the black line and the random distribution by the green line. d, Decay in linkage disequilibrium with distance (Po-0 excluded). The black line shows r2 between SNPs; the red line shows phylogenetic r2 (Supplementary Information section 6).

Both iterative and de novo assembly improved accuracy, with the latter being most effective at divergent loci (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 10). As assessed with about 1.2 Mb of genomic dideoxy data3,18,19 (Supplementary Information section 4), the substitution error rate was about 1 per 10 kb in single-copy regions, and about tenfold higher in transposable-element-rich regions. Further, RNA-seq reads covered about 100,000 SNPs per accession with 99.72% concordance (Supplementary Table 5), and junction sequences for 66 of 68 (97%) long indels and imbalanced substitutions were confirmed by PCR and dideoxy sequencing (Supplementary Table 8). The substitution error rate for our assemblies was comparable to that reported for four other A. thaliana genome assemblies4.

Genome-wide patterns of ancestry

The ancestral relationships of the accessions vary genome-wide. We computed phylogenies20 across 1.25 million biallelic, non-private SNPs (Supplementary Information section 6). The ancestry of each pair of accessions within a phylogeny was quantified by using the genome-wide distribution of the minimum clade size of the subphylogeny containing the pair (Fig. 1c). Despite their wide geographical origins, with the exception of Po-0 and Oy-0, all pairs have distributions similar to that of an unstructured sample. The probability of recent co-ancestry is slightly higher than expected for a few pairs of accessions, with extended haplotype sharing at a minority of loci (Supplementary Figs 11–15), perhaps reflecting selective sweeps7. Both linkage disequilibrium and correlation between neighbouring phylogenies decrease by 50% within 5 kb (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 16). Variation among the 18 accessions is similar to a diverse global A. thaliana sample7,8 in nucleotide diversity (Supplementary Figs 11–15), correlation with genomic features (Supplementary Tables 9–12) and structural variants (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Gene annotation and transcript diversity

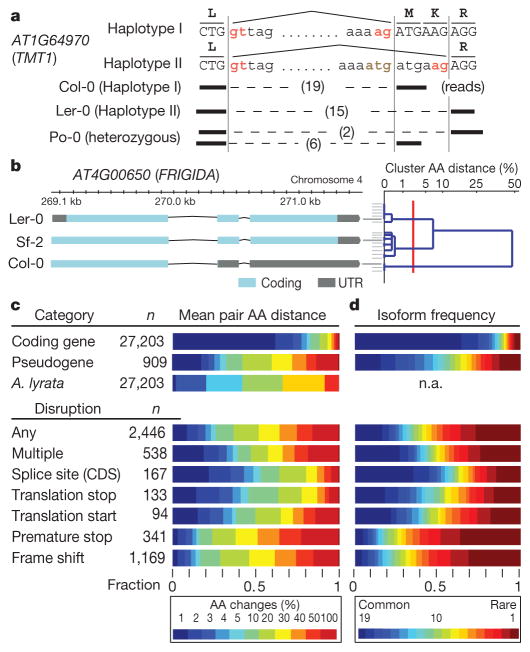

A naive projection of the coordinates of the 27,206 nuclear protein-coding genes from Col-0 (TAIR10 annotation) onto the 18 genomes predicted that 93.4% of proteins were changed in at least one accession, with 32% of the total being affected by genic deletions, premature termination codons, or other disruptions (Supplementary Table 13). This large tally of disrupted genes implies that reference annotations cannot be transferred reliably; in fact, re-annotation reveals compensating changes, ensuring that many genes encode apparently functional proteins (Fig. 2a). Thus, in 96.2% of the 8,757 genes affected, the naive annotations were replaced by an alternative gene model in at least one accession (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 18). We predicted new splice sites in 64% of the 2,572 genes with splice site disruptions (in 696 cases the new sites were within 30 bp of the original ones; see, for example, Fig. 2a). Finally, there was evidence of alternative splicing in 2,106 genes (Supplementary Information sections 10.10–10.13).

Figure 2. Transcript and protein variation.

a, Example of a splice site change between two haplotypes for the gene AT1G64970. Haplotype I (Col-0) is spliced with an intron 6 bp (two amino acids) shorter than haplotype II (Ler-0); Po-0 (heterozygous) shows allele-specific expression of both. b, Re-annotation of the FRIGIDA locus showing annotations for accessions Sf-2 (functional), and Col-0 (truncated by a premature stop) and Ler-0 (non-functional) (Supplementary Figs 18 and 42). Right: the 19 accessions are shown clustered on the basis of the AA distance between their FRIGIDA amino-acid sequences. Common isoform clusters (at distance 2% or less; red line) are shown, leading to three clusters with three, seven and nine accessions. c, Proteome diversity for coding genes, pseudogenes and A. lyrata genes (top) and for genes with disruptions (bottom). Reported is the fraction of genes with relative AA distance to other accessions (average over pairs) in the given colour-coded interval (Supplementary Information section 10.7). d, Frequency of isoforms of coding genes and pseudogenes (top), and those associated with different disruptions (bottom).

For genome annotation and expression analyses (for example Figs 2–4), we generated 78-bp RNA-seq reads from two biological replicates of seedling mRNA (about 9.5 million mapped reads per accession, including Col-0; Supplementary Information section 9, and Supplementary Table 14). We integrated read alignments21 with sequence-based gene predictions22 by using mGene.ngs (Supplementary Information sections 9–10.3, and Supplementary Fig. 19). On average, 24,681 coding genes were predicted for each accession. Comparison of Col-0 de novo predictions with TAIR10 annotations (Supplementary Table 16) showed that these predictions are more accurate (transcript F-score 65.2%) than using the genome sequence (mGene22, 59.6%) or RNA-seq alignments alone (Cufflinks23, 37.5%; Supplementary Table 17). Finally, we consolidated the de novo annotations by incorporating TAIR10 annotations where applicable (Supplementary Information section 10.4, and Supplementary Fig. 20); novel transcript structures for a known TAIR10 gene were only accepted if each newly predicted intron was confirmed by RNA-seq alignments, or if the reference gene model was severely disrupted.

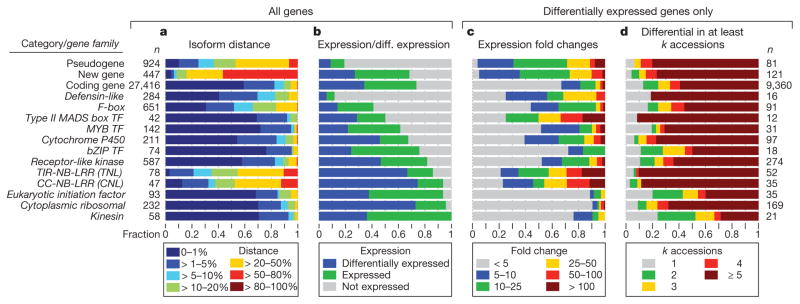

Figure 4. Protein diversity and gene expression vary by gene category or family.

The numbers next to each row are gene counts. The gene families were selected from Supplementary Figs 26 and 39–41 to represent the breadth of observed variation. a, Distribution of average AA distances to other accessions (compare with Fig. 2c). b, Fraction of unexpressed, expressed and differentially expressed genes (expressed is a superset of differentially expressed). c, Distribution of genes categorized by fold change (between lowest and highest across 19 accessions). d, Distribution of the numbers of accessions contributing to differential expression. TF, transcription factor; CC, coiled-coil; TIR, Toll interleukin-1 receptor; NB-LRR, nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat.

We found, on average, 42,338 transcripts per accession (excluding Col-0), of which 5.5% (2,316) were novel (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 18). In each accession there were, on average, 319 novel genes (or gene fragments) supported by RNA-seq (Table 1); 717 novel genes were found in total, 496 whose sequence was present in Col-0 but not annotated, and 221 absent from the Col-0 genome but present in the de novo assemblies of the accessions. We found protein or expressed sequence tag matches for 74.9% of the new genes, primarily from A. thaliana, A. lyrata or other Brassicaceae species (Supplementary Information sections 10.8 and 10.9).

Table 1.

Summary of gene predictions

| Type | Total

|

Novel

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per accession | RNA-seq confirmed (%) | Per accession | RNA-seq confirmed (%) | |

| Genes | 33,197 | 62.7 | 319 | 88.4 |

| Transcripts | 42,338 | 59.9 | 2,316 | 84.2 |

| Introns | 127,640 | 83.3 | 1,345 | 72.1 |

| Start codons | 33,264 | n.a. | 503 | n.a. |

| Stop codons | 33,720 | n.a. | 528 | n.a. |

| Intron retentions | 1,192 | 78.1 | 873 | 76.5 |

| Exon skips | 80 | 80.5 | 38 | 76.7 |

‘Total’ and ‘novel’ are average counts over all 19 accessions. ‘RNA-seq confirmed’ gives the percentage fully confirmed using independent RNA-seq data (three tissues) for Can-0, the most divergent accession.

For accession Can-0, we generated additional independent higher coverage RNA-seq data from seedling, root and floral bud, which we used to confirm 83.3% of re-annotated introns (read alignment over splice junction) and 59.9% of transcripts (confirmation of every intron, or read coverage of 50% of the transcript for single exon transcripts; Table 1). We also obtained additional RNA-seq data for Col-0 and found similar confirmation rates for the reference annotation (Supplementary Table 19). Moreover, for Can-0 we confirmed 72.1% and 84.2% of novel introns and transcripts. Many novel introns stemmed from splice disruptions that tended to be weakly expressed so RNA-seq evidence was scarcer (Supplementary Fig. 22). Finally, more than 75% of novel alternative splicing events were supported by RNA-seq (Supplementary Information section 10.5).

Proteome diversity

To understand the effect of genetic diversity on proteins, it is insufficient to study isolated DNA polymorphisms in the context of the reference annotation. We therefore defined the distance between two amino-acid (AA) sequences by the fraction of amino-acid residues that did not align identically in their global alignment. For example, for FRIGIDA, between Col-0 and Sf-2, a premature stop codon leads to an AA distance of 49% (Fig. 2b). In 77% of proteins, the mean AA distance between all accessions was less than 3% (Fig. 2c). However, on average, 747 proteins per accession had a distance larger than 50% to any TAIR10 protein, with markedly greater variation for pseudogenes. As expected, variation between A. thaliana and its congener A. lyrata24 exceeds that observed among A. thaliana accessions (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 23). Disruptions to splice sites and translation start and stop codons typically caused less severe effects than premature stop codons or frame shifts (Fig. 2c) when compensating splice sites created alternative in-frame splicing (for example Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 24).

Next, we identified protein isoforms across accessions (Fig. 2b, right; distinct isoforms differ by at least roughly 2% AA distance; Supplementary Information section 10.7). For 80% of protein coding genes the most frequent isoform was very common (frequency at least 15 out of 19), whereas isoforms for pseudogenes usually occurred at lower frequency. Moreover, isoforms for large disruptions were rare (frequency 3 or less) for 37% of affected genes (Fig. 2d). This was most pronounced for premature stops and frameshifts, where purifying selection is expected to be strongest.

As expected3,7, disease resistance genes of the coiled-coil and Toll interleukin 1 receptor subfamilies of the Nucleotide-Binding Leucine Rich Repeat (NB-LRR) gene family were predicted to encode the most variable proteins (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 26). F-box and defensin-like genes implicated in diverse processes including defence25,26 were also highly variable. In contrast, housekeeping genes showed little variation.

Variation in seedling gene expression

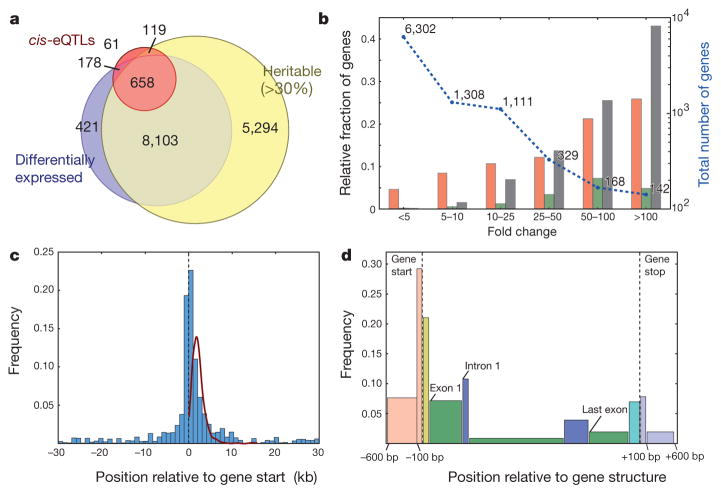

Median expression heritability of protein-coding genes was 39%, similar to that of novel genes (36%) and pseudogenes (38%), and more than for non-coding RNAs (30%) (Supplementary Fig. 27). In total, 75% (20,550) of protein-coding genes (and 21% of non-coding RNAs and 21% of pseudogenes) were expressed in at least one accession (false discovery rate (FDR) 5%), and 46% (9,360) of expressed protein-coding genes were differentially expressed between at least one pair of accessions27 (Fig. 3a; FDR 5%, Supplementary Information section 11). Of these, 19% (1,750) had more than tenfold expression changes, and 1.5% (142) more than 100-fold (Fig. 3b). For about 60% of genes, at least five accessions contributed to expression variation (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Information section 11.8).

Figure 3. Quantitative variation of coding gene expression.

a, The overlap between heritable (more than 30%) and differentially expressed (FDR 5%) genes, and genes with a cis-eQTL (FDR 5%). b, Differentially expressed genes and genes with cis-eQTLs (FDR 5%) categorized by fold change. Nucleotide variants (orange bars; 647 cis-eQTLs) are SNPs and single-base indels; copy-number variants (green bars; 42 cis-eQTLs) are regions with elevated coverage in aligned genomic reads in at least one accession; gene structural variants (black bars; 227 cis-eQTLs) are accession-specific deletions, insertions or changes to the gene model. c, The spatial distribution of nucleotide-variant eQTLs relative to the start of protein-coding genes (FDR 5%, overlapping genes removed; n = 647). The line shows density of gene length. d, Frequencies of nucleotide-variant eQTLs in protein-coding genes, classified by component (bar widths are proportional to the components’ average physical lengths): red bars, upstream; yellow bars, 5′ untranslated region; green bars, coding sequence exons; blue bars, introns; cyan bars, 3′ untranslated region; grey bars, downstream.

Although the small sample size (19) precludes genome-wide association scans to identify trans expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), we identified potential cis-acting nucleotide variants, copy-number variants and gene structural variants (for example large indels and gene structure changes) associated with expression for 9% (836) of differentially expressed genes (FDR 5%; Supplementary Information section 12.2; we assessed gene-copy-number variation as in Supplementary Information section 12.4). Much of this variation was highly heritable (Fig. 3a). Consistent with identifying likely causal variants, 85% and 93% of associated SNPs and single-nucleotide indels for cis-eQTLs were within 5 and 10 kb of the gene, respectively, and were strikingly concentrated in the 100-bp promoter region and 5′ genic sequences (Fig. 3c, d). This was also true for heritable intron retention events, in which most cis associations were within the intron or less than 1 kb distant (Supplementary Fig. 32). Our results corroborate the general findings28–31 of extensive cis regulation of gene expression in A. thaliana. Neither environmental variation nor population structure markedly affected expression variation (Supplementary Information section 13). Copy-number and structural variants were associated with expression in 3% (240) of differentially expressed genes, including 45% (64 out of 142) of genes with more than 100-fold differences (Fig. 3b), consistent with array studies29.

Differential gene expression varied by gene ontology (GO) and gene family (Fig. 4b–d, Supplementary Table 24 and Supplementary Figs 39–41). Seventeen of the 18 GO classifications that were enriched for differential expression (P < 10−3) concerned response to the biotic environment, including pathogen defence and the production of glucosinolates32 to deter herbivores (Supplementary Table 24). These include NB-LRR genes (echoing protein variation), of which 74% were differentially expressed at up to 400-fold change, and for which many accessions typically contributed to differential expression (Fig. 4b–d). Patterns for housekeeping genes (such as ribosomal proteins, eukaryotic initiation factors or kinesins) were markedly different: although many were differentially expressed, fold changes were generally small, with variation more often being limited to a few accessions (Fig. 4b–d). Differentially expressed genes generally had much higher nucleotide diversity at synonymous sites relative to other expressed genes, a pattern also observed but less extreme at non-synonymous sites (Supplementary Table 25). This suggests that differences in expression level were not due solely to reduced selective constraint.

The type II MADS box transcription factor family33 showed striking expression polymorphisms (Fig. 4b–d), including for the FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC)34 and MADS AFFECTING FLOWERING (MAF) genes35. FLC, a floral inhibitor expressed highly in accessions that require prolonged cold (vernalization) to flower36, varied more than 400-fold (Supplementary Fig. 42). F-box and defensin-like genes were exceptional in that expression was restricted in a minority of genes (41% and 12%, respectively; Fig. 4b), perhaps reflecting tissue-specific or environment-specific expression25,37. Our data suggest that high turnover for some F-box families in the A. thaliana lineage7 extends to gene expression as well.

Conclusion

Our study goes beyond cataloguing polymorphisms7,17 to provide genome sequences for a moderately sized population sample (see also refs 4, 16). In doing so, we were able to annotate each genome largely independently of the Col-0 reference. We found that disruptive polymorphisms were frequently compensated for, thereby conserving coding potential and highlighting the limitation of inferring consequences of polymorphisms in the absence of complete sequence data.

Our assemblies are accurate and largely complete in single-copy regions, although additional work will be needed to assemble the roughly 20% of the genome comprising repeats and transposable elements. Disentangling copy variation, long insertions and other genomic rearrangements remains a challenge. The methods we developed are of immediate relevance to the broader A. thaliana 1001 Genomes Project5 and to other organisms, and highlight the importance of RNA-seq data for annotation.

Finally, despite using only 19 accessions, we fine-mapped cis-eQTLs to small genomic regions (less than 10 kb), suggesting that analogous genome-wide scans in the more than 700 derived MAGIC lines could have single-gene mapping resolution for some loci. Our findings indicate that the MAGIC lines, for which population structure is largely mitigated9, will be an important and complementary resource to genome-wide association studies in A. thaliana populations10.

METHODS SUMMARY

We used the same seed stocks for Col-0 and the 18 accessions Bur-0, Can-0, Ct-1, Edi-0, Hi-0, Kn-0, Ler-0, Mt-0, No-0, Po-0, Oy-0, Rsch-4, Sf-2, Tsu-0, Wil-2, Ws-0, Wu-0 and Zu-0 that originated the MAGIC lines. DNA and RNA sequencing was performed with standard (DNA) or modified (RNA-seq) Illumina protocols. All methods are described fully in Supplementary Methods; software is available from the authors on request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Jiang and C. Brown for technical help; P. Dikjwel, K. Schneeberger and D. Weigel for providing sequence data in advance of publication; and J. Flint, M. Tsiantis, E. Feil, L. Hurst, A. Wachter and D. Weigel for comments on the manuscript. Funding was provided by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) BB/F022697/1 (to R.M. and P.X.K.), BB/D016029/2 (to P.X.K and R.M.), BB/F020759/1 (to N.P.H.) and BB/F019793/1 to P.K. (PI E. Birney), by core funding of the Max Planck Society (to G.R.), the German Research Foundation RA1894/1-1 and RA1894/2-1 (to G.R.), Volkswagen Stiftung (to O.S.), the National Science Foundation (NSF) 0929262 (to R.C. and C.T.) and 0820985 (to R.C., Principal Investigator L. Sieburth), and award no. KUK-I1-002-03 (to N.P.H), made by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). D. Buck, I. Ragoussis and colleagues in the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics Genomics Core performed most of the genomic sequencing, supported by the Wellcome Trust Core grant 090532/Z/09/Z. Contribution no. 11-388-J from the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions R.M., R.C., G.R., P.X.K. and C.T. conceived and led the project. R.M. and X.G. developed and performed genome assembly and analysis. R.C, J.S. and E.O. sequenced the transcriptomes and performed analyses. R.L. performed the ancestral recombination graph analysis. C.T. and K.L.H. performed population genetics analyses. S.J.S., G.J., G.R. and A.K. developed and applied RNA-seq alignment. J.B., G.R., S.J.S., A.K. and R.B. annotated the genomes and analysed their proteins. P.D., G.R. and O.S. performed differential expression analyses. O.S. and P.D. performed genetic association analysis of expression traits. V.T.S. processed data for display in Gbrowse. N.P.H., E.B. and X.G. performed experimental confirmations. P.K. and P.D. constructed the Ensembl version of the variation data. E.K. performed genomic sequencing. R.M., R.C., G.R., P.X.K., C.T., X.G. and O.S. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

DNA sequencing data are deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/) under accession number ERP000565. RNA sequencing data are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE30814. Data are also available at http://mus.well.ox.ac.uk/19genomes. Genome annotations are viewable at http://fml.mpg.de/gbrowse-19g.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Johanson U, et al. Molecular analysis of FRIGIDA, a major determinant of natural variation in Arabidopsis flowering time. Science. 2000;290:344–347. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentley DR, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008;456:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ossowski S, et al. Sequencing of natural strains of Arabidopsis thaliana with short reads. Genome Res. 2008;18:2024–2033. doi: 10.1101/gr.080200.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneeberger K, et al. Reference-guided assembly of four diverse Arabidopsis thaliana genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10249–10254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107739108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weigel D, Mott R. The 1001 genomes project for Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol. 2009;10:107. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-5-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000;408:796–815. doi: 10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark RM, et al. Common sequence polymorphisms shaping genetic diversity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2007;317:338–342. doi: 10.1126/science.1138632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeller G, et al. Detecting polymorphic regions in Arabidopsis thaliana with resequencing microarrays. Genome Res. 2008;18:918–929. doi: 10.1101/gr.070169.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kover PX, et al. A multiparent advanced generation inter-cross to fine-map quantitative traits in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atwell S, et al. Genome-wide association study of 107 phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana inbred lines. Nature. 2010;465:627–631. doi: 10.1038/nature08800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMullen MD, et al. Genetic properties of the maize nested association mapping population. Science. 2009;325:737–740. doi: 10.1126/science.1174320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durrant C, et al. Collaborative cross mice and their power to map host susceptibility to Aspergillus fumigatus infection. Genome Res. 2011;21:1239–1248. doi: 10.1101/gr.118786.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao J, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of multiple Arabidopsis thaliana populations. Nature Genet. 2011 Aug 28; doi: 10.1038/ng.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lunter G, Goodson M. Stampy: a statistical algorithm for sensitive and fast mapping of Illumina sequence reads. Genome Res. 2011;21:936–939. doi: 10.1101/gr.111120.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li R, et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 2010;20:265–272. doi: 10.1101/gr.097261.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keane TM, et al. Mouse genomic variation and its effect on phenotypes and gene regulation. Nature. doi: 10.1038/nature10413. in the press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gore MA, et al. A first-generation haplotype map of maize. Science. 2009;326:1115–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.1177837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai AG, Denton-Giles M, Mueller-Roeber B, Schippers JH, Dijkwel PP. Positional information resolves structural variations and uncovers an evolutionarily divergent genetic locus in accessions of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol Evol. 2011 May 27; doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr038. advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordborg M, et al. The pattern of polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song YS, Hein J. Constructing minimal ancestral recombination graphs. J Comput Biol. 2005;12:147–169. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2005.12.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jean G, Kahles A, Sreedharan VT, De Bona F, Ratsch G. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. Unit 11.6. Ch 11. Wiley; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schweikert G, et al. mGene: accurate SVM-based gene finding with an application to nematode genomes. Genome Res. 2009;19:2133–2143. doi: 10.1101/gr.090597.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu TT, et al. The Arabidopsis lyrata genome sequence and the basis of rapid genome size change. Nature Genet. 2011;43:476–481. doi: 10.1038/ng.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silverstein KA, Graham MA, Paape TD, VandenBosch KA. Genome organization of more than 300 defensin-like genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:600–610. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gagne JM, Downes BP, Shiu SH, Durski AM, Vierstra RD. The F-box subunit of the SCF E3 complex is encoded by a diverse superfamily of genes in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11519–11524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162339999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keurentjes JJ, et al. Regulatory network construction in Arabidopsis by using genome-wide gene expression quantitative trait loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1708–1713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610429104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plantegenet S, et al. Comprehensive analysis of Arabidopsis expression level polymorphisms with simple inheritance. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:242. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West MA, et al. Global eQTL mapping reveals the complex genetic architecture of transcript-level variation in Arabidopsis. Genetics. 2007;175:1441–1450. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.064972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, Cal AJ, Borevitz JO. Genetic architecture of regulatory variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Res. 2011;21:725–733. doi: 10.1101/gr.115337.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howe GA, Jander G. Plant immunity to insect herbivores. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:41–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufmann K, Melzer R, Theissen G. MIKC-type MADS-domain proteins: structural modularity, protein interactions and network evolution in land plants. Gene. 2005;347:183–198. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheldon CC, et al. The FLF MADS box gene: a repressor of flowering in Arabidopsis regulated by vernalization and methylation. Plant Cell. 1999;11:445–458. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.3.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratcliffe OJ, Kumimoto RW, Wong BJ, Riechmann JL. Analysis of the Arabidopsis MADS AFFECTING FLOWERING gene family: MAF2 prevents vernalization by short periods of cold. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1159–1169. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lempe J, et al. Diversity of flowering responses in wild Arabidopsis thaliana strains. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:109–118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmid M, et al. A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nature Genet. 2005;37:501–506. doi: 10.1038/ng1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.