Abstract

Purpose

We introduce a new method to selectively detect iron oxide contrast agents using an acoustic wave to perturb the spin-locked water signal in the vicinity of the magnetic particles. The acoustic drive can be externally modulated to turn the effect on and off, allowing sensitive and quantitative statistical comparison and removal of confounding image background variations.

Methods

We demonstrate the effect in spin-locking experiments using piezoelectric actuators to generate vibrational displacements of iron oxide samples. We observe a resonant behavior of the signal changes with respect to the acoustic frequency where iron oxide is present. We characterize the effect as a function of actuator displacement and contrast agent concentration.

Results

The resonant effect allows us to generate block-design “modulation response maps” indicating the contrast agent’s location, as well as positive contrast images with suppressed background signal. We show the AIRS effect stays approximately constant across acoustic frequency, and behaves monotonically over actuator displacement and contrast agent concentration.

Conclusion

AIRS is a promising method capable of using acoustic vibrations to modulate the contrast from iron oxide nanoparticles and thus perform selective detection of the contrast agents, potentially enabling more accurate visualization of contrast agents in clinical and research settings.

Keywords: MR contrast agent, contrast mechanisms, positive contrast, iron-oxide contrast agents, spin-lock

Introduction

Superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles are widely used as contrast agents in magnetic resonance molecular imaging (1–3). Due to the large susceptibility difference between injected SPIO nanoparticles and surrounding tissues, the presence of iron oxide nanoparticles can often be manually determined in T2*-weighted images by darkened voxels due to the loss of MR signal around local field inhomogeneities induced by iron oxide. SPIO nanoparticles have been utilized in various contexts ranging from cancer imaging (4,5) to cell-tracking (6,7) to MR angiography (8,9).

This manual SPIO locating process is problematic in a complex tissue background with other naturally occurring regions of dark contrast (e.g. air or bone) or in regions with low intrinsic signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). This has been a long-standing practical challenge of SPIO nanoparticles’ effectiveness as a negative contrast agent in-vivo. The predominant compensating strategy has been the acquisition and comparison of pre- and post- injection scans. However, this process is confounded by the generally slow biodistribution times of these agents which requires a relatively lengthy pre-post comparison interval. Therefore, the comparison is corrupted by subject motion, various forms of biological noise introduced between the scan sessions, and other modulations in signal intensity that make subtractive imaging and other quantitative pre-post comparison methods infeasible.

Instead of the contrast modulation from a one-time injection, a more desirable paradigm would be to repeatedly switch the contrast agent “on” and “off” in rapid succession; each k-space line (or single-shot image) could be acquired twice within seconds, and the resulting images would be compared (i.e. subtracted or subjected to a statistical test). This form of rapid comparison would be less sensitive to the low-frequency base-line intensity drift effects caused by motion, physiological noise, and instrumental drift.

In this work, we describe a new contrast mechanism for selectively detecting iron oxide nanoparticle contrast agents, Acoustically Induced Rotary Saturation (AIRS), whereby a rotating frame resonance condition is established between spin-locked water magnetization and time-oscillating magnetic fields generated by acoustic-frequency vibration of contrast agents. We utilize the rotary saturation effect (10, 11) where the spin-locked magnetization is resonantly sensitive to oscillating fields at the frequency ω = γB1lock. Previous related experiments have used variants of the rotary saturation effect to detect oscillating electrical currents for the purpose of neuronal current imaging (12,13). In our method, we utilize the fact that the resonant frequency can be conveniently brought into the auditory frequency range, ideal for vibrating magnetic particles or tissues using external sound or mechanical vibration. The relative motion between the oscillating nanoparticles and the neighboring water causes the spin-locked water to experience an oscillating local magnetic field on-resonance with the rotating frame resonance condition which in turn causes a resonant rotation of the spin-locked magnetization away from the spin-lock field, exhibiting an image intensity change after the readout sequence. This resonant effect can be modulated “on” or “off” by adjusting either the vibration or the spin-lock frequency to on- or off- resonance, or by turning on or off the acoustic stimulation. Either case allows consecutive acquisitions of a given k-space line or single-shot image to be acquired with and without the SPIO’s contrast modulation.

We present results demonstrating the AIRS principle with a liquid phantom and characterize the effect of the vibration frequency, amplitude and contrast agent concentration. Furthermore, we show the ability to generate an fMRI-like activation map, hereby referred to as “modulation response map,” of contrast agent presence through a functional imaging-type “block design” experiment where the effect of the contrast agent is cycled on and off. The rapid interleaving of on/off states is thus robust to the slowly varying modulations in image intensity, which confound conventional pre- and post- injection comparisons. The ability to detect contrast agents with a functional imaging model also allows quantifiable measurement of the contrast agent effect using well-established statistical analysis tools.

Theory

During a spin-lock preparation sequence, a 90°x excitation is first used to bring the magnetization vector M to ŷ in the rotating frame of reference (rotating at the Larmor frequency). A spin-lock field B1lock also rotating at the Larmor frequency is then applied along the ŷ in the rotating frame. Since the only field present in the rotating frame (B1lockŷ) and the magnetization are co-linear, this field “locks” the rotating frame transverse magnetization along this axis. The rotating frame Larmor frequency (ω1lock = γB1lock) dictates the frequency needed for an external transverse field to alter the energy of the spin system in the locked state. Thus, longitudinal relaxation (T1ρ) in the spin-locked state is sensitive to external fields oscillating at γB1lock. In the rotary saturation effect, the presence of a second field γBrotarysat during spin-lock driven at or near the angular frequency γB1lock will coherently rotate the magnetization away from the spin-lock axis (10,11,12). These rotating frame effects in response to fields oscillating at γB1lock are therefore analogous to conventional RF excitation and T1 relaxation, which occur, respectively, in response to coherent driving fields or intrinsic fluctuating fields oscillating near ω0 = γB0.

The dynamics of the phenomenon can be more conveniently understood in a doubly-rotating frame, which rotates around the spin-lock axis at a frequency ω1lock. In this frame the applied field Brotarysat is stationary along the z axis. The equations of motion for the magnetization in the spin-lock condition within the doubly-rotating frame are presented with the y axis aligned along the spin-lock direction:

| (Eq. 1) |

with

| (Eq. 2) |

where intrinsic T2* and T1ρ relaxations occur in accordance with the rotating frame equilibrium magnetization Mρ.

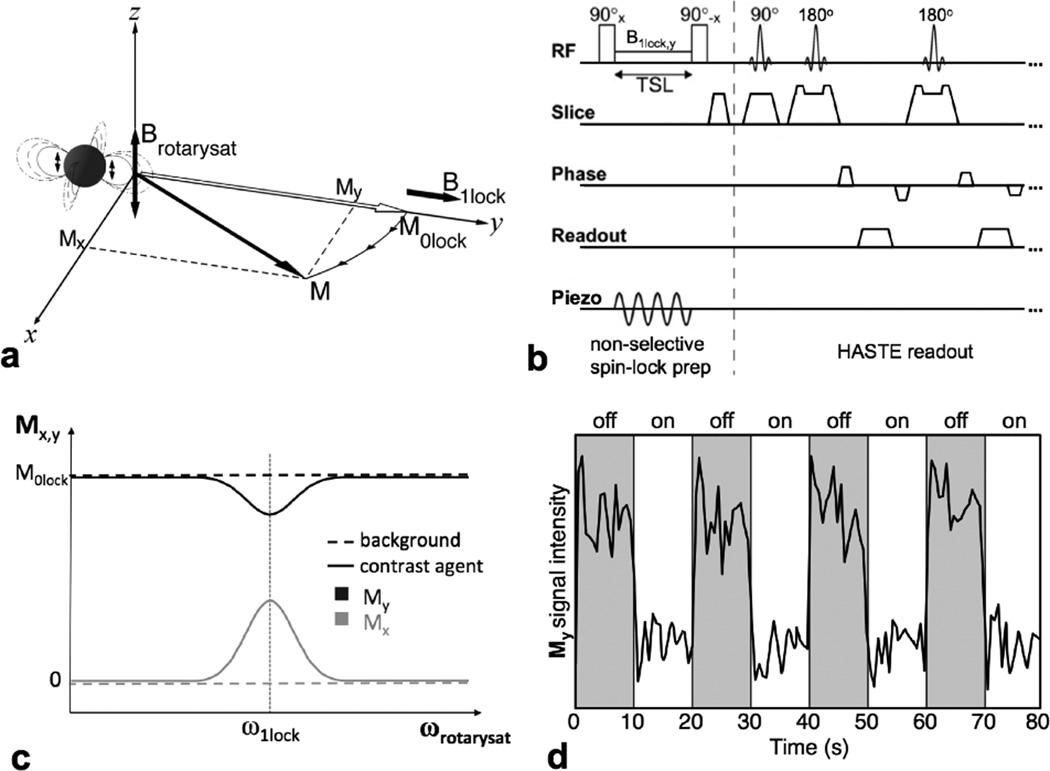

An important aspect of the Rotary Saturation effect is that its effect on the magnetization is narrowband. The magnetization undergoes rotation in the doubly-rotating frame only when ωrotarysat and ω1lock are matched, due to the excitation analogy mentioned above. This resonant feature is illustrated in Fig. 1, and can be obtained quantitatively in the solution for Equations 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the method, ignoring relaxation. (a) After a 90° excitation, a rotary saturation field B1lock is applied to spin lock the magnetization along the y axis, resonantly sensitizing the magnetization M (initially locked to M0lock) to magnetic fields Brotarysat oscillating at a frequency γB1lock. Iron oxide nanoparticles can be vibrated to generate this Brotarysat experienced by the local water and produce a resonant rotation of the magnetization M0lock away from the y axis. (b) The pulse sequence is comprised of a spin-lock period, during which the iron oxide sample is vibrated by a piezoelectric actuator. The 90° pulse flips back either Mx or My to the z axis for imaging by a HASTE readout. The choice of whether to readout the x or y component of M is set by the phase of the flip-back 90° pulse. (c) The expected response of the measured Mx or My component (generating positive or negative contrast, respectively) as the frequency of the sample vibration ωacoustic (and thus rotary saturation field ωrotarysat) is swept through the resonance condition (ωrotarysat = γB1lock). (d) The expected intensity variation in the vicinity of the contrast agent as the sample vibrations are switched between on- and off-resonance conditions. The block-design response is similar to that of functional imaging and can be analyzed by similar statistical methods yielding an fMRI-like activation map indicating the presence of the magnetic nanoparticle contrast agent (see Fig. 2d).

Previous experiments demonstrated the Rotary Saturation effect with rotary saturation fields Brotarysat generated by coils outside solid and liquid samples (11) and wire current dipoles in liquid phantoms (12,13). In our method, the rotary saturation field, Brotarysat is generated by the vibrating iron oxide contrast agents themselves.

An accumulation of magnetic nanoparticles in a static homogenous B0 field exhibits a magnetic field perturbation approximated by that of a magnetized sphere, as described in (14):

| (Eq. 3) |

where Δχ is the difference in bulk magnetic susceptibility between the sphere and the surroundings, a is the sphere radius, r is the distance to the center of the sphere, and θ is the angle between r and B0.

For small sinusoidal displacements of a magnetic nanoparticle cluster, an approximately sinusoidally time-varying field is generated (see Appendix). Our method uses this contrast agent-derived field as the rotary saturation field Brotarysat, causing a nutation of the magnetization M in voxels near the contrast agents when its frequency ωrotarysat is near the spin-lock resonant frequency ω1lock (Fig. 1a).

At the end of the spin-lock preparation the magnetization is flipped to ẑ by the choice of either a 90°−x or 90°y followed by a transverse spoiler, consequently returning either the My (by 90°−x) or Mx (by 90°y) component for subsequent imaging (Fig. 1b). The component encodes the resonant AIRS effect as a signal loss as the magnetization is nutated away from ŷ, while the Mx component encodes the effect as a signal gain. For small nutation angles, Mx (which behaves according to the sine of the angle) will experience a larger effect than My (which behaves according to the cosine of the angle) (Fig. 1c). Choosing the Mx component will also result in a positive contrast image, because Mx grows during the rotation while the unperturbed background magnetization stays along ŷ with no x̂ component. In either case, the signal intensity depends upon the strength of the rotary saturation field, which is correlated with contrast agent concentration.

Furthermore, the signal is frequency-dependent due to the rotary saturation resonance condition, and thus selective contrast can be obtained by comparing the signal between resonant (ωrotarysat = ω1lock) and non-resonant states (ωrotarysat ≠ ω1lock) with an fMRI-like block design experiment, interleaving on-resonance and off-resonance acquisition blocks (Fig. 1d). By comparing the signal change between conditions across all image voxels, we interrogate the strength of this effect spatially and generate a modulation response map with statistical methods utilized in functional imaging analyses.

Methods

Experiments were performed in a spherical phantom (10 cm diameter) filled with a solution of 0.52 ml of Gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist, Berlex Laboratories) yielding a T1 measured by inversion recovery of 400 ms. Two NMR spherical bulb microcells (Wilmad 18µL spherical microcell inserts, Wilmad-LabGlass), one containing various concentrations of 10 nm Fe2O3 nanoparticles (Fe concentration = 200 µg/ml), and the other containing Fomblin® Perfluoropolyether (PFPE) oil (Solvay Chemicals), a control fluid with low signal and little susceptibility difference from the phantom solution, were lowered vertically into the liquid phantom. The microcells are composed of a 3 mm inner-diameter, 5 mm outer-diameter glass spherical shell, where the sample is contained, adjoined to a 0.9 mm inner-diameter, 1.1 mm outer-diameter glass capillary tube. The top of each glass tube (extending out from the phantom opening) was attached by epoxy to a piezoelectric bender actuator driven by a piezoelectric amplifier (T220-A4-203X model actuator and EPA-104-115 amplifier, Piezo Systems Inc, Woburn MA). Driven with an audio frequency function generator, the piezo induces vertical displacements of the samples oscillating in time at a chosen frequency ωacoustic. Because of the relationship previously described between the rotary saturation field and the vibrating contrast agent sample, ωrotarysat = ωacoustic. The displacements were calibrated and measured with laser doppler vibrometry. A third stationary microcell filled with the identical iron oxide concentration was also lowered into the phantom to provide a second control to demonstrate the effect’s dependence upon properly tuned vibrational motion.

A spin-lock prepared single-shot HASTE pulse sequence (Fig. 1b) was used in a 1.5T scanner (Siemens Avanto, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen Germany) to capture images with 256×256 matrix, 12-cm FOV, 5mm slice thickness, TE of 14 ms, and TR of 3.0 s. The piezoelectric sinusoidal actuations are gated to be active only within the 100 ms spin-lock preparation sequence, during which the magnetization is manipulated due to the rotary saturation phenomenon and subsequently imaged with the HASTE readout.

To generate the modulation response map to indicate contrast agent presence, a block design experiment was conducted by acquiring a set of 100 single-shot HASTE images while switching resonance states (on-resonance: ω1lock = ωrotarysat, off-resonance ω1lock ≠ ωrotarysat) in 20 image blocks. In our experiment, , and switched between 75 Hz and 50 Hz. The iron oxide sample Fe concentration was 200 µg/ml and vibrated sinusoidally with peak-to-peak displacement amplitude 250 µm. To generate a modulation response map, voxel-by-voxel analysis of the signal changes between on and off resonance states was carried out using standard fMRI methods; FEAT (FMRI Expert Analysis Tool) Ver. 5.98, in FSL (FMRIB's Software Library, www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). Time-series statistical analysis was performed using FILM (FMRIB's Improved Linear Model) and contrasts were cluster corrected at threshold of Z > 2.3 (p < 0.05).

The strength of the AIRS effect in the liquid phantom setup was studied as a function of Fe concentration, nanoparticle sample vibration displacement amplitude, and nanoparticle sample vibration frequency. The contrast agent samples used in these characterization experiments were contained in cylindrical capillary tubes (1.1 mm inner-diameter, 1.3 mm outer-diameter, Fisher Scientific). The average image intensity values in a 2 mm radius ROI centered at the contrast agent location were obtained in both on-resonance (ω1lock = ωrotarysat) and off-resonance (ω1lock = ωrotarysat + Δω) conditions, where was 25 Hz. The signal change ΔS/S, was computed as the on-resonance to off-resonance signal difference over the off-resonance signal intensity. The Fe concentration in the samples were varied between 0 µg/ml (control) and 200 µg/ml (0 µg/ml, 50 µg/ml, 100 µg/ml, 150 µg/ml, 200 µg/ml) with and displacement 500 µm. Vibration peak-to-peak amplitude was varied between 10 µm and 500 µm (10 µm, 20 µm, 50 µm, 80 µm, 100 µm, 200 µm, 300 µm, 400 µm, 500 µm) with a 200 µg/ml Fe concentration sample and . The AIRS effect on contrast agent vibration frequency was studied at 50 Hz, 100 Hz, 150 Hz, and 200 Hz, with a vibrational displacement of 150 µm and 200 µg/ml Fe concentration sample and ω1lock swept in intervals of 2Hz between 24 Hz below and 24 Hz above each value to form rotary saturation spectra.

Bloch simulation was performed to corroborate the relative changes in linewidth and peak intensities of the rotary saturation spectra across resonant frequencies. The time-evolution of the magnetization during the 100 ms spin-locked preparation according to the modified doubly-rotating frame Bloch equations (Eq 1–2) was simulated with a MATLAB code solver with parameters T1 = 395 ms, T2 = 316 ms, T2* = 46 ms, T1ρ was taken from the R2=1/T2 and R1=1/T1 values using the equation T1ρ=2/(R2+R1) (10), and Brotarysat derived from the magnetic field perturbation of a cylindrical accumulation of iron oxide nanoparticles (14): in cylindrical coordinates, where the difference in bulk magnetic susceptibility difference between the cylinder and the surroundings Δχ = 1.5 × 10−5, the cylinder radius a = 0.55mm, and the distance to the center of the cylinder ρ = 2mm.

Extending the AIRS method to enable positive contrast imaging, the 90° flipback direction after the spin-lock preparation was switched to be along ŷ, resulting in signal growth for voxels near the contrast agent due to Mx being the component to be subsequently imaged, as detailed in the theory section. With 200 µg/ml samples in the liquid phantom setup with bulb samples, vibrated with a peak-to-peak amplitude of 150 µm and at , we acquired 50 images on-resonance () and 50 images without vibration for reference, primarily to remove the effect of B0 field inhomogeneity manifesting as a signal confound. The reference images were subtracted from the on-resonance images and averaged over time to produce the final positive contrast image. We then performed statistical analysis on the voxel signal changes between on-resonance and no-vibration groups using the FSL FEAT and FSL FILM methods described above with the same parameters, obtaining modulation response maps to further validate the location of the vibrating contrast agent sample. We also studied the intensity of the positive contrast signal, averaged over a 4 mm radius ROI centered at the contrast agent location, as a function of Fe concentration at 50 µg/ml, 100 µg/ml, 75 µg/ml, 100 µg/ml, 150 µg/ml, and 200 µg/ml samples.

Results

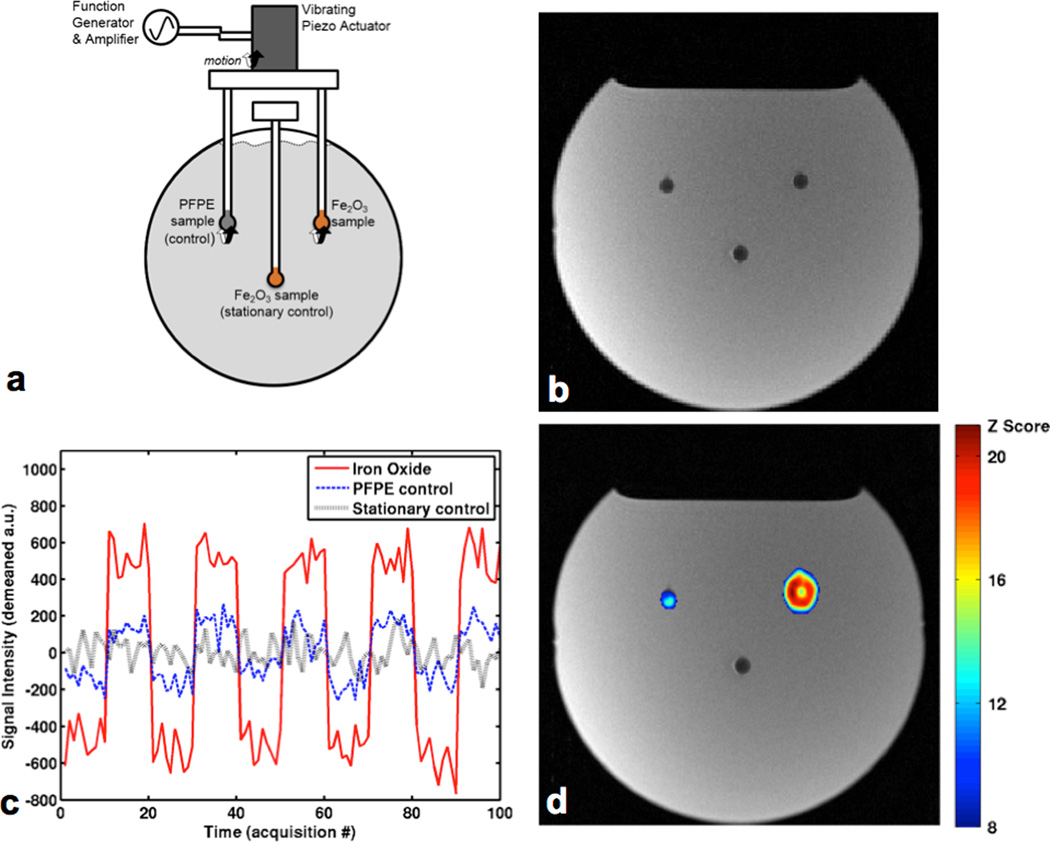

The essential capabilities of the AIRS method are demonstrated in Fig. 2. Fig. 2b shows a conventional T2-weighted image of the liquid phantom setup and demonstrates the limitation that similarly hypointense contrast sources appear undifferentiated; the iron oxide samples cannot be distinguished from the fluorinated oil sample. As the block design experiment proceeds through on-resonance and off-resonance acquisition blocks, the signal intensity is modulated in voxels near the vibrating contrast agent sample, as shown by the single voxel signal intensity timeseries in Fig. 2c. The modulations in signal intensity clearly match the timing of the switches between on/off -resonance states. These signal modulations can be observed particularly clearly in the sequence of raw images acquired during the block design experiment, displayed in Supporting Video S1.

Fig. 2.

Liquid phantom validation experiment. (a) A spherical Gd-doped H2O solution phantom contains three glass spherical bulbs; two contain aqueous Fe2O3 samples and one contains Fomblin PFPE oil. The Fomblin and Fe2O3 samples are simultaneously vibrated by piezoelectric drive while the other Fe2O3 acts as a stationary control. (b) A conventional T2-weighted coronal slice acquisition showing all three samples as undifferentiated hypointense regions. (c) Time course of voxel intensities near each sample over the duration of the block-design experiment where interleaved blocks of on-resonance (acoustic drive and spin-lock frequency both at 75 Hz) and off-resonance (acoustic drive at 50 Hz and spin-lock frequency at 75 Hz) images were acquired at 10 time points per block. The acquisitions were performed with the negative contrast version of the method, with the 90° flipback pulse along the x axis. The signal modulation is shown to be highest near the vibrating iron oxide sample. (d) Modulation response map of the block design experiment highlighting the location of the vibrating contrast agent sample, generated by voxel-wise statistical analysis of intensity changes between on- and off-resonance acquisitions. The highest z scores occur near the vibrating contrast agent source. Residual contrast appearing near the fluorinated oil sample is likely due to differences in turbulent motion between the two vibration settings which introduce different T2* shortenings.

To generate a modulation response map, voxel-by-voxel statistical analysis of the signal changes between on and off resonance states was carried out using standard fMRI GLM analysis methods. Fig. 2d shows the highest z scores corresponding to voxels in proximity to the vibrated contrast agent sample, demonstrating the selective contrast agent detection capability of the AIRS contrast mechanism. Some residual contrast appearing near the fluorinated oil sample is likely primarily due to differences in turbulent motion between the two vibration settings that introduce slightly different T2* shortening during the acquisitions.

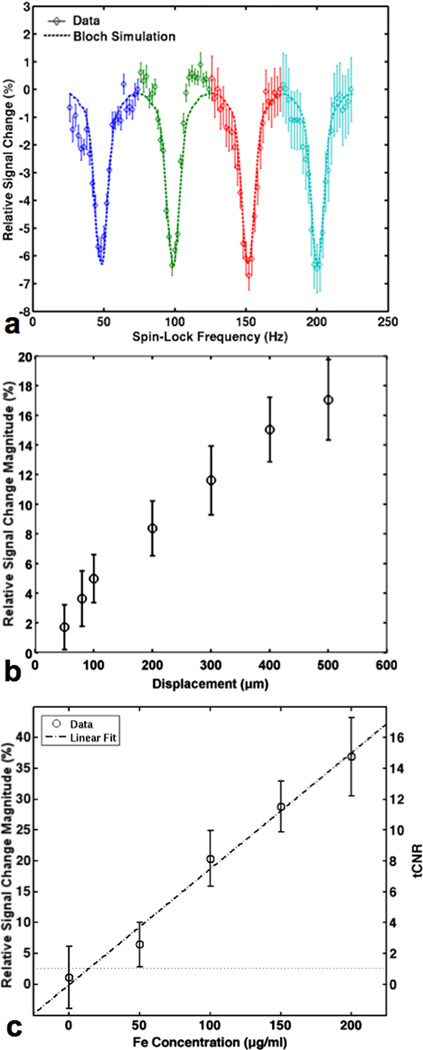

The rotary saturation spectra in Fig. 3a demonstrate the AIRS effect as a function of both the iron oxide vibration frequency as well as the spin-lock frequency . For each vibration frequency (blue curve = acoustic drive at 50 Hz, green curve = acoustic drive at 100 Hz, red curve = acoustic drive at 150 Hz, cyan curve = acoustic drive at 200 Hz), a rotary saturation spectrum is obtained by sweeping through . The scatter plots display measured data, which show that both the amplitude of the AIRS effect as well as its linewidth stay approximately constant across nanoparticle vibration frequency these observations are well-modeled by the Bloch simulation results which are plotted concurrently in the dashed-line curves.

Fig. 3.

(a) Characterization of the AIRS effect from the negative contrast version of the experiment as a function of spin-lock frequency with the acoustic drive of Fig. 2 set at each of 4 different frequencies (blue curve = acoustic drive at 50 Hz, green curve = acoustic drive at 100 Hz, red curve = acoustic drive at 150 Hz, cyan curve = acoustic drive at 200 Hz), with vibration displacement set to 150 µm and the sample concentration at 200 µg Fe/ml. Signal loss and the line-width of the resonance effect are approximately constant for the different iron oxide vibration frequencies. The solid curves are the Bloch equation simulation results using parameters based on the phantom (T1 = 395 ms, T2 = 316 ms, T2* = 46 ms), and Brotarysat derived from a magnetic field perturbation model of a magnetized cylinder (14). (b) The magnitude of the relative signal change between on and off resonance conditions as a function of piezo actuator displacement (in the apparatus of Fig. 2) as measured by a laser Doppler vibrometer. The actuator vibration frequency was set to 50 Hz and spin-lock frequency was either 75 Hz (off-resonance state) or 50 Hz (on-resonance state), and the sample concentration was 200 µg Fe/ml. (c) Characterization of the AIRS effect (relative signal change magnitude between resonance states) in the apparatus of Fig. 2 as a function of iron concentration for a contrast agent vibration frequency of 50 Hz and spin-lock frequency set to either 75 Hz (off-resonance state) or 50 Hz (on-resonance state), and displacement was set to 500 µm. tCNR values as a function of Fe concentration shown alongside a linear fit with R2= 0.93, which intersects with the dotted line (tCNR = 1) indicating a sensitivity limit of 20 µg/ml.

Fig. 3b shows the strength of the AIRS effect increasing with higher nanoparticle vibration amplitude, consistent with the increased driving field Brotarysat derived from increased relative motions between the spin-locked water and the contrast agent B field source. Fig. 3c shows the increasing strength of the AIRS effect as sample Fe concentration increases, also due to the increased driving field Brotarysat. which in this case is derived from higher susceptibility iron oxide solutions. The effect strength measured in tCNR is also shown in Fig. 3c, along with a linear fit of the data (R2= 0.93) which intersects the tCNR = 1 dotted line at 20 µg/ml, indicating the method’s sensitivity limit under the experimental conditions.

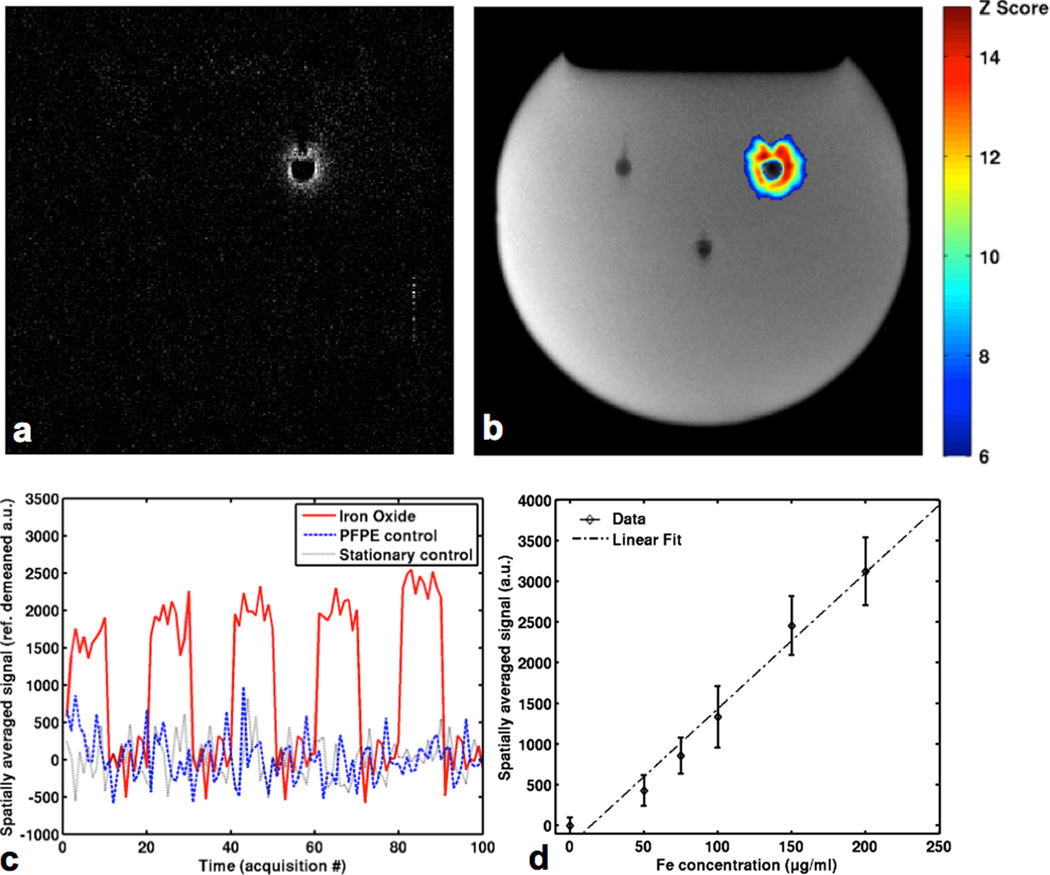

Fig. 4 shows positive contrast imaging of iron oxide nanoparticles using the AIRS method modified with a phase-shifted flipback pulse. In Fig. 4a, we observe the bright signal region unambiguously identifying the vibrating contrast agent sample. Both control samples and the background regions of the phantom exhibit nearly nonexistent signal. A modulation response map analysis of the on-resonance vs. no-vibration acquisition conditions is shown in Fig. 4b, demonstrating signal modulation only in the vicinity of the vibrating contrast agent sample. This effect can be observed in the timeseries signal intensity with the reference intensities subtracted in Fig. 4c; the voxels near the vibrating iron oxide sample show a positive signal change during the on-resonance condition blocks. Even though the reference condition here is no-vibration instead of off-resonance as with the negative contrast experiments, because the absence of motion is effectively the same as being off-resonance in the spin-lock acquisition, the same basic phenomena is generated; this flexibility allows the reference condition to be chosen according to what is most convenient and practical for the experiment or scan session. Across the various concentrations of iron oxide samples tested, Fig 4d. shows a nearly linear correlation between the positive contrast signal and Fe concentration, along with a linear fit of the data (R2= 0.97).

Fig. 4.

Positive contrast imaging of iron oxide nanoparticles with the liquid phantom apparatus of Fig 2a, by switching the 90° flipback pulse direction to be along the y axis. All experiments were conducted with the contrast agent vibration frequency at 75 Hz and spin-lock frequency set to 75 Hz. (a) Positive contrast image with 100 µg/ml Fe sample and spin-lock frequency 75 Hz (on-resonance). 100 acquisitions were taken, interleaving 10 on-resonance acquisitions and 10 no-vibration acquisition blocks. Each set of 50 acquisitions were averaged across time and the no-vibration average was subtracted from the on-resonance average to eliminate signal artifacts due to field inhomogeneity. (b) Modulation response map generated by statistical analysis of the signal difference between interleaved acquisition blocks. The highest z scores occur near the vibrating contrast agent source. (c) Time course of spatially averaged signal intensities near each sample over the experiment, demonstrating positive signal change during on-resonance acquisitions. (d) Spatially averaged positive contrast signal in the vicinity of the vibrating contrast agent sample increases with Fe concentration in a nearly linear fashion. The dashed line shows a linear fit of the signal data with R2= 0.97.

Discussion

Our experiments demonstrate the feasibility of selectively imaging iron oxide contrast agents through a narrowband contrast modulation mechanism based on the rotary saturation effect. Separation of the agent’s contrast from the background may enable quicker and more accurate visualization of injected MR iron oxide contrast agents in both research and clinical settings, particularly in acquisition scenarios with complex background contrast featuring multiple signal voids with various causes.

The characterization experiments show that signal change due to AIRS effect appears to be well-behaved across a number of physical parameters; of particular importance is its nearly linear correlation between effect intensity and iron oxide concentration in clinically relevant ranges, enabling not only simple visual evaluations of relative concentration levels, but also potentially the development of quantification techniques measuring contrast agent concentration.

Although we have demonstrated a preliminary in-vitro validation of the technique here with a phantom setup established to primarily investigate the basic physical phenomena, our results indicate the AIRS contrast mechanism can be readily extended to tissue-mimicking gel phantoms and in-vivo settings by the application of shear waves propagating through the sample media. The AIRS effect has been shown to effectively modulate contrast near the contrast agent with small vibration amplitudes in the tens of microns, the typical range of displacement amplitudes generated in shear waves through tissue during MR elastography with acoustic or piezoelectric drivers already used on patients during MR imaging (15,16).

In addition to addressing the problem of selective detection of contrast agents, techniques based on the AIRS mechanism may also be able to engage the recurrent goal in MR molecular imaging of improving the detection threshold for iron oxide nanoparticle agents. The instantly switchable contrast modulation ability in AIRS allows for hundreds of on-off cycles to be performed during acquisition, resulting in statistically boosted sensitivity in a manner similar to fMRI experiments, where signal changes less than 1% are routinely detectable. Based on our experiments, we demonstrated the sensitivity of our approach to be at least 20 Fe ug/ml for a 5-minute scan. This sensitivity is within the range of iron concentrations found in-vivo within tumors of animal studies, where typical biologically acceptable dosages of iron oxide nanoparticles between 10 and 100 mg Fe/kg (well below the mouse LD50 toxicity dose of 2000 mg Fe/kg (17)), result in iron oxide accumulations in various tumors at concentrations of 20–50 ug Fe/ml (18–20).

In comparison to several recently proposed “positive contrast” approaches with similar goals of selectively imaging iron oxide contrast agents, our method offers a different range of tradeoffs. Off-resonance positive contrast imaging techniques typically use spectrally selective RF (SSRF) pulses to excite off-resonance spins susceptibility-shifted by the iron oxide nanoparticles (21) or suppress the on-resonance water with bandwidth-limited saturation (22). The frequency range of excitation in these methods is best determined by prior knowledge of the concentration of the agent, which is often infeasible in in-vivo settings. These methods can also suffer from artifacts due to B0 inhomogeneity, as the spins in the inhomogeneous fields with Larmor frequencies in the off-resonance passband become excited along with the iron oxide susceptibility-induced resonance shifts. Although B0 field inhomogeneity also affects each spin-lock image acquisition with the AIRS technique, the artifacts that appear in both on- and off-resonance conditions disappear once the relative signal change between the conditions (caused only by B fields fluctuating at ) is computed. Positive contrast imaging with ultrashort echo time (UTE) sequences has also been demonstrated by subtracting an ultra-short echo time (e.g. 50 µs) acquisition and a longer echo time (e.g. 20 ms) acquisition, reversing the negative contrast due to T2 decay (23,24). However, this method is limited by potentially confounding subtractive contrast due to variations in the T2 of background tissue.

A potential limitation regarding the use of AIRS in-vivo is that with the proposed shear wave drive method, the entire tissue would tend to vibrate in bulk; thus, other sources of susceptibility difference (air, iron stores, etc…) within the vibrated tissue may also be picked up by methods based on the AIRS effect. However, this limitation is not unique and should affect any imaging method dependent upon the susceptibility properties of the iron oxide agents, including other positive contrast iron oxide imaging techniques.

Another reasonable concern regarding this property that shear waves tend to move connected tissue areas together is that the potentially reduced relative displacements may not generate the oscillating field strengths required for the AIRS method to be effective. However, focal lesions which would often be the target of these nanoparticle agents typically express mechanical properties significantly different from the surrounding background tissue. For example, hepatocellular carcinoma and focal nodular hyperplasia have vastly different shear stiffness than the normal liver tissue they are embedded in. (25) Propagating shear waves impinging upon the interface between these heterogeneous tissue regions face an acoustic impedance mismatch and thus would generate high relative displacement between tissue areas on the two sides of the interface with amplitude similar to that of the propagating wave (26–28). As these shear wave amplitudes are typically delivered around 50–100 µm in-vivo, this places the relative displacement properties of the shear wave in tissue setup in a similar range as our piezoelectric actuator in the liquid phantom. Furthermore, for scenarios where there is reduced mechanical elastic coupling between the two tissue regions, (e.g. a fluid interface between the normal and pathological tissue), high relative displacement would also be expected across the interface.

This interface source of displacement also contributes to the expected effectiveness of the AIRS method for more complex geometries and various distributions of sizes of nanoparticle accumulations that would exist in-vivo. Additionally, as shown by Schenck (14), the geometry of the magnetic perturber affects the local B field distribution. For our experiments, we used both spherical and cylindrical samples - prototypical shapes representing two extremes of the distribution of geometries a focal lesion (containing targeted nanoparticles) would exhibit, resulting in faster (1/r^3 for spherical) and slower (1/r^2 for cylindrical) ΔB field falloff. The success of our experiments demonstrates that the AIRS technique would work on a wide range of geometries and field falloffs. Regardless of the particular falloff rate or nanoparticle accumulation geometry, the AIRS phenomenon has been shown to be locally present with the nanoparticle sample and strongest near the center of the accumulation.

We also note that there is a possible “microscopic effect” not yet mimicked by our experiments for conditions in which relative motion at the nanometer scale between individual nanoparticles and local spin-locked water can generate the same AIRS contrast and manifest macroscopically in the image acquisitions. This is a potential research direction to further investigate and extend the AIRS effect.

Another challenge for in-vivo applications of the AIRS effect is the limitation to areas in the body where mechanical shear waves from the surface can penetrate to generate the tens of microns of displacement required for detection by the AIRS effect. Thus, tissue locations closer to the body’s surface such as the liver and breast would be better suited than areas with less direct access, such as the heart. Additionally, even for tissues that have sufficient vibration amplitude, the potentially inhomogeneous propagation of shear waves within the tissue may negatively influence both relative and more quantifiable determinations of contrast agent concentration. However, this can be addressed by normalizing the effect according to measurements of the shear wave inhomogeneity, which can be acquired through MR elastography techniques.

The independence of the AIRS effect shown across a wide acoustic vibration frequency range eliminates the need to optimize vibration frequency on the acquisition side, allowing us to set the frequency to ensure sufficient penetration and propagation of shear waves in tissues of interest. MR Elastography experiments have demonstrated the appropriate range of driving frequencies for these tissues to be between 50 and 300 Hz (16). These frequencies are well within the possible range for resonance with spin-locking fields.

A primary feature of the AIRS mechanism is the ability to rapidly induce contrast modulation with the iron oxide agents already present and thus shift the examination to an entirely post-injection paradigm, avoiding the long biological uptake time required by a typical pre- and post-injection comparison. As previously noted, scanner drift, subject motion, and other 1/f biological noise during this uptake time introduce confounding artifacts that currently make in-vivo automated detection methods impractical; by circumventing these limitations, we demonstrate the viability of automated mapping of contrast agents and potentially reduced uncertainty related to manual identification. Eliminating the need for pre-injection scans may also improve clinical throughput by obviating subsequent scan sessions or by reducing the extended durations of single sessions.

Conclusion

In this work we have introduced a novel contrast and contrast control mechanism to selectively image iron oxide contrast agents by modulating their contrast through a narrowband resonant spin-lock mechanism. Deploying this contrast mechanism in a block-design experiment which repeatedly cycles the effect of the agent on and off enables the removal of background contrast for sensitive and selective detection of the contrast agents via a statistically generated modulation response map. We demonstrate our method through validation experiments in phantoms, and we show the strength of the AIRS effect to be generally well-behaved and robust across contrast agent concentration, displacement, and operating vibration frequency, indicating feasibility for its practical implementation in in-vivo settings.

The unique contrast modulation mechanism enables an entirely post-injection process that is quantitative in nature and robust against slow drifts in signal intensity due to scanner drifts and physiological motion. We also anticipate the method’s clinical potential for reducing the conventional ambiguities associated with visualizing the presence of iron oxide contrast agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the contributions of Wei-Tang Chang for assistance in pulse sequence modifications, and Vivek Srinivasan and Jonghwan Lee for assistance in calibrating piezoelectric actuators. This research was carried out at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at the Massachusetts General Hospital, using resources provided by the Center for Functional Neuroimaging Technologies, P41RR14075, a P41 Regional Resource supported by the Biomedical Technology Program of the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), National Institutes of Health. This work was also made possible by Grant Number T32 EB001680 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB).

Appendix

Consider a spherical iron oxide nanoparticle cluster with field perturbation as previously described in Eq. 3: . In Cartesian coordinates, this becomes:

The field at any point (x0, y0, z0) can be approximated as linear in z for small excursions about (x0, y0, z0). Consider a small time-varying displacement Δz(t) ≪ a of the nanoparticle cluster, where a is the sphere radius. For any point outside the nanoparticle cluster, r > a, the new magnetic field perturbation can be characterized with linear approximation around the operating point (x0,y0,z0) by:

For sinusoidal displacements Δz(t) = Δz sin(ωt) after substitutions and differentiation, we obtain:

where C1 and C2 are constants:

We observe the time-varying component of ΔBz to be sinusoidal. Thus, for small sinusoidal displacements of a magnetic nanoparticle cluster, an approximately sinusoidally time-varying field is generated.

References

- 1.Hahn MA, Singh AK, Sharma P, Brown SC, Moudgil BM. Nanoparticles as contrast agents for in-vivo bioimaging: current status and future perspectives. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2011;399(1):3–27. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terreno E, Castelli DD, Viale A, Aime S. Challenges for molecular magnetic resonance imaging. Chemical Reviews. 2010;110(5):3019–3042. doi: 10.1021/cr100025t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoo D, Lee JH, Shin TH, Cheon J. Theranostic magnetic nanoparticles. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2011;44(10):863–874. doi: 10.1021/ar200085c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen JE, Chan L, Shieh DB, Gu FX. Iron oxide nanoparticles for targeted cancer imaging and diagnostics. Nanomedicine : Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine. 2012;8(3):275–290. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu MK, Park J, Jon S. Targeting strategies for multifunctional nanoparticles in cancer imaging and therapy. Theranostics. 2012;2(1):3–44. doi: 10.7150/thno.3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahmoudi M, Hosseinkhani H, Hosseinkhani M, Boutry S, Simchi A, Journeay WS, Subramani K, Laurent S. Magnetic resonance imaging tracking of stem cells in vivo using iron oxide nanoparticles as a tool for the advancement of clinical regenerative medicine. Chemical Reviews. 2011;111(2):253–280. doi: 10.1021/cr1001832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor A, Wilson KM, Murray P, Fernig DG, Lévy R. Long-term tracking of cells using inorganic nanoparticles as contrast agents: are we there yet? Chemical Society Reviews. 2012;41(7):2707–2717. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35031a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moriarty JM, Finn JP, Fonseca CG. Contrast agents used in cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging: current issues and future directions. American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs : drugs, devices, and other interventions. 2010;10(4):227–237. doi: 10.2165/11539370-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saeed M, Wendland MF, Higgins CB. Blood pool MR contrast agents for cardiovascular imaging. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI. 2000;12(6):890–898. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200012)12:6<890::aid-jmri12>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abragam A. Principles of Nuclear Magnetism. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1961. pp. 566–570. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Redfield A. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Saturation and Rotary Saturation in Solids. Physical Review. 1955;98(6):1787–1809. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witzel T, Lin FH, Rosen BR, Wald LL. Stimulus-induced Rotary Saturation (SIRS): a potential method for the detection of neuronal currents with MRI. NeuroImage. 2008;42(4):1357–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halpern-Manners NW, Bajaj VS, Teisseyre TZ, Pines A. Magnetic resonance imaging of oscillating electrical currents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(19):8519–8524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003146107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schenck JF. The role of magnetic susceptibility in magnetic resonance imaging: MRI magnetic compatibility of the first and second kinds. Medical Physics. 1996;23(6):815–850. doi: 10.1118/1.597854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muthupillai R, Lomas DJ, Rossman PJ, Greenleaf JF, Manduca A, Ehman RL. Magnetic resonance elastography by direct visualization of propagating acoustic strain waves. Science. 1995;269(5232):1854–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.7569924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mariappan YK, Glaser KJ, Ehman RL. Magnetic resonance elastography: a review. Clinical Anatomy. 2010;23(5):497–511. doi: 10.1002/ca.21006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Neil MJ, editor. The Merck Index – An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals. 13th. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck and Co., Inc.; 2001. p. 519. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Shin MC, Yang VC. Magnetic Targeting of Novel Heparinized Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Evaluated in a 9L-glioma Mouse Model. Pharm Res. 2014;31(3):579–592. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1182-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi GH, Seo SJ, Kim KH, Kim HT, Park SH, Lim JH, Kim JK. Photon Activated Therapy (PAT) using Monochromatic Synchrotron x-rays and Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in a Mouse Tumor Model. Radiation Oncology. 2012;7:184. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seo SJ, Jeon JK, Jeong EJ, Chang WS, Choi GH, Kim JK. Enhancement of Tumor Regression by Coulomb Nanoradiator Effect in Proton Treatment of Iron-Oxide Nanoparticle-Loaded Orthotopic Rat Glioma Model. Journal of Cancer Therapy. 2013;4(11):25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunningham CH, Arai T, Yang PC, McConnell MV, Pauly JM, Conolly SM. Positive contrast magnetic resonance imaging of cells labeled with magnetic nanoparticles. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2005;53(5):999–1005. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuber M, Gilson WD, Schär M, Kedziorek DA, Hofmann LV, Shah S, Vonken EJ, Bulte JWM, Kraitchman DL. Positive contrast visualization of iron oxide-labeled stem cells using inversion-recovery with ON-resonant water suppression (IRON) Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2007;58(5):1072–1077. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boada FE, Wiener E. Ultra-short echo time difference (USTED) data acquisition for T2* contrast reversal. Proceedings of the 14th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Seattle, Washington, USA. 2006:189. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Girard OM, Du J, Agemy L, Sugahara KN, Kotamraju VR, Ruoslahti E, Bydder GM, Mattrey RF. Optimization of iron oxide nanoparticle detection using ultrashort echo time pulse sequences: comparison of T1, T2*, and synergistic T1–T2* contrast mechanisms. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2011;65(6):1649–1660. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeh WC, Li PC, Jeng YM, Hsu HC, Kuo PL, Li ML, Yang PM, L PH. Elastic Modulus Measurements of Human Liver and Correlation with Pathology. Ultrasound in Med & Biol. 2002;28(4):467–474. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00489-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou S, Robert JL, Fraser J, Shi Y, Xie H, Shamdasani V. Finite Element Modeling for Shear Wave Elastography; IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium, Orlando FL, USA; 2011. pp. 2400–2403. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmeri M, McAleavey S, Fong K, Trahey G, Nightingale K. Dynamic Mechanical Response of Elastic Spherical Inclusions to Impulsive Acoustic Radiation Force Excitation. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 2006;53(11):2065–2079. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2006.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calle S, Remenieras JP, Hachemi ME, Patat F. Shear Wave Elastography: Modeling of the Shear Wave Propagation in Heterogeneous Tissue by Pseudospectral Method; IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium, Montreal, Canada; 2004. pp. 24–27. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.