Abstract

Over the past two decades, many studies have identified significant contributions of toxic β-amyloid peptides (Aβ) to the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which is the most common age-dependent neurodegenerative disease. AD is also recognized as a disease of synaptic failure. Aβ, generated by sequential proteolytic cleavages of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by BACE1 and γ-secretase, is one of major culprits that cause this failure. In this review, we summarize current findings on how BACE1-cleaved APP products impact learning and memory through proteins localized on glutamatergic, GABAergic, and dopaminergic synapses. Considering the broad effects of Aβ on all three types of synapses, BACE1 inhibition emerges as a practical approach for ameliorating Aβ-mediated synaptic dysfunctions. Since BACE1 inhibitory drugs are currently in clinical trials, this review also discusses potential complications arising from BACE1 inhibition. We emphasize that the benefits of BACE1 inhibitory drugs will outweigh the concerns.

Keywords: BACE1, Alzheimer’s β-secretase, APP, Abeta peptides, synapses, NMDA receptors, AMPA receptors, dopamine receptors

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common age-dependent neurodegenerative disease and AD pathogenesis results in progressive loss of synapses and increasingly severe cognitive dysfunction. The so-called “toxic β-amyloid (Aβ) theory” has been the dominant theme in AD research over the past twenty years and has also attracted the most drug discovery efforts. Unfortunately, none of the clinical trials based on this “Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis” (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002) that have been completed have produced successful results. Due to the increasing numbers of failed mid- to late-stage trials, growing discussions and suspicions regarding the validity of the Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis have been provoked in the field (Castello et al., 2014; Giacobini and Gold, 2013). Considering various studies that argue against the causative role of toxic Aβ in AD pathogenesis [i.e., no correlation of plaque density with severity of dementia (Perrin et al., 2009)] and the lack of patients diagnosed with amyloid plaque-only dementia (Benilova et al., 2012; Skaper, 2012), it is legitimate to question whether work on the Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis has reached an impasse.

However, despite various controversies between encouraging pre-clinical experimental results and less favorable clinical outcomes, it remains too early to abandon research on “toxic Aβ”. There is a consensus that data from clinical mutations in APP, presenilin-1 and −2, and the ApoE4 allele support the toxic Aβ theory, in cases of both early and late onset AD (Tanzi, 2012). The dichotomy between animal studies and clinical trials has likely arisen due to multiple factors, which may include trial designs, chemical (such as BACE1 inhibitor LY2886721 showing liver toxicity) vs. mechanistic (i.e. non-selective γ-secretase inhibition due to inhibition of Notch and other signaling molecules) toxicity, and/or in vivo specificity of immunotherapy (De, 2014; Saxena, 2010; Toyn and Ahlijanian, 2014). Despite the failed clinical trials, there is still promise for developing more specifically targeted drugs to reduce Aβ-mediated synaptic toxicity.

Aβ, mainly Aβ40-Aβ42/43, is generated from amyloid precursor protein (APP) through sequential cleavages by two secretases: β- and γ-secretase. BACE1, also known as Asp2 and memapsin 2, was discovered to be the β-secretase (Hussain et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2000; Sinha et al., 1999; Vassar et al., 1999; Yan et al., 1999). γ-secretase is a complex composed mainly of four transmembrane proteins: presenilin-1 or −2, nicastrin, Aph1, and Pen2 (De Strooper et al., 1998; Francis et al., 2002; Li et al., 2000; Yu et al., 2000). Most familial mutations in presenilin-1 or −2 favor production of Aβ42/43 by shifting the normal balance between Aβ40 and Aβ42/43. Since BACE1 initiates the generation of Aβ, its activity is expected to be highly correlated with overall Aβ-mediated pathological functions. Indeed, in AD brains, BACE1 levels are increased ~2-fold compared to healthy non-demented brains (Fukumoto et al., 2002; Holsinger et al., 2002; Li et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2003). Hence, inhibition of BACE1 activity is a logical strategy for preventing or reversing Aβ-mediated impairments in AD patients. More encouragingly, phenotypes seen in BACE1-null mice are relatively mild when compared to disrupted γ-secretase functions in animals (De et al., 2010; Francis et al., 2002; Kelleher, III and Shen, 2010; Vassar et al., 2014).

Targeted inhibition of BACE1 will reduce Aβ, and pathological level of Aβ has been broadly shown to impair synaptic functions over the past two decades. A large number of publications have revealed direct interactions of Aβ with various proteins important for synaptic plasticity. It has become clear that Aβ can impact learning and memory by acting through glutamatergic, GABAergic, and dopaminergic synapses, rather than working through a single system. While some controversial results have arisen, this review aims to summarize the collective findings of how Aβ affects these systems and to sort out more commonly observed mechanistic insights. We aim to further highlight the practical benefits of BACE1 inhibition for improving synaptic functions in patients.

Brief overview of BACE1

BACE1 is a typical aspartyl protease with a classical bilobal structure; two active aspartate motifs (D93TG and D289SG) are located in a separate lobe. BACE1 is first synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) as a 501 amino acid immature precursor protein (proBACE1) and its prodomain (residues 1–21) is removed by furin-like proprotein convertases during maturation in the Golgi compartment (Bennett et al., 2000; Creemers et al., 2001). BACE1 undergoes N-glycosylation on four sites (N-153, N-172, N-223 and N254) (Haniu et al., 2000) and acetylation on seven Lys residues (Lys-126, Lys-275, Lys-279, Lys-285, Lys-299, Lys-300 and Lys-307) in the ER. Lys residues are also the targets for ubiquitination. For example, BACE1 activity is post-translationally regulated via ubiquitination at Lys-501, as mutation of this residue impairs its endocytosis to lysosomes for degradation (Kang et al., 2012; Tesco et al., 2007). Others have shown that BACE1 is also ubiquitinated at Lys-203 and Lys-382, as site-directed mutagenesis of these two residues reduces the proteasomal degradation of BACE1 and affects APP processing at the β site, as well as Aβ production (Wang et al., 2012b). In the Golgi, BACE1 deacetylation (Costantini et al., 2007) and palmitoylation in four C-terminal Cys residues (Cys474/478/482/485) for lipid raft localization (Benjannet et al., 2001; Bhattacharyya et al., 2013; Vetrivel et al., 2009) occur. Interestingly, most post-translational modifications, except for the di-sulfide linkage, are not essential for BACE1 proteolytic activity per se, as recombinant BACE1 produced in bacteria lacks these modifications but is sufficiently active. However, certain glycol modifications appear to alter its proteolytic activity in vivo due to targeted cellular trafficking. For example, BACE1 is modified by N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), a sugar-bisecting enzyme highly expressed in brain (Kizuka et al., 2015). Loss of this modification will target BACE1 to late endosomes/lysosomes for accelerated lysosomal degradation, while enhanced bisecting GlcNAc in BACE1, as is likely the case in AD brains, facilitates Aβ generation due to increased stability. BACE1 was initially found to be phosphorylated at Ser-498 (Walter et al., 2001), and this phosphorylation is linked to BACE1 cellular trafficking (He et al., 2005; Pastorino et al., 2002). BACE1 is also phosphorylated by the p25/Cdk5 complex at Thr252, which increases BACE1 activity by cdk5/P25 (Song et al., 2015).

After maturation, BACE1 is normally transported along the secretory compartment, where the luminal BACE1 protease domain will encounter and cleave APP, which has the same type I transmembrane topology, at the β-site. As an aspartyl protease, BACE1 proteolytic activity is favored in low acidic environments, with its maximum proteolytic activity being at ~pH 4.5 as shown by in vitro assays (Tomasselli et al., 2003; Turner, III et al., 2002). It is clear that BACE1 processes its substrates such as APP more efficiently in the relatively more acidic trans-Golgi Network (TGN) and endosome compartments than in the more neutral ER compartment (Das et al., 2013). Altering trafficking of BACE1 in secretory compartments is therefore another strategy to reduce or enhance BACE1 activity (Jiang et al., 2014; Tan and Evin, 2012; Vassar et al., 2014). For instance, enhanced retention of BACE1 by an ER protein such as RTN/Nogo in the ER can significantly reduce BACE1 cleavage of APP, thereby decreasing Aβ production (Araki et al., 2012; Deng et al., 2013; He et al., 2004; Shi et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2013; Wojcik et al., 2007). Increased trafficking of BACE1 in the more acidic endosomes by cellular trafficking proteins such as a Vps10p domain-sorting receptor sortilin (Finan et al., 2011), the small GTPase ADP ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6) (Sannerud et al., 2011), Rab-GTPases Rab11 (Udayar et al., 2013), and Sorting nexin 12 (Zhao et al., 2012) results in significant increases in Aβ generation. Golgi-localized γ-ears containing ADP ribosylation factor-binding (GGA) family proteins can bind BACE1 via the di-leucine motif and impact not only its endosomal trafficking, but also its stability (He et al., 2002; He et al., 2005; Santosa et al., 2011; Tesco et al., 2007; von et al., 2015; Wahle et al., 2005; Walker et al., 2012). Depletion of both GGA1 and GGA3 induces a rapid and robust elevation of BACE1, and such an effect will likely be interfered with by flotillin, which can compete with GGA proteins for binding to the same dileucine motif in the BACE1 tail (John et al., 2014). In neurons, BACE1 is targeted to both axons and dendrites, and its preferential transport to the axonal terminus versus somatodendrites can be regulated by altered levels of calsyntenin-1 (Steuble et al., 2012; Vagnoni et al., 2012), retromer vps35 (Wang et al., 2012a; Wen et al., 2011), RTN3 (Deng et al., 2013), Rab11, and Eps15 homology domain proteins (Buggia-Prevot et al., 2014; Buggia-Prevot et al., 2013; Udayar et al., 2013). The localization of BACE1 in synaptic sites can impact the processing of its substrates.

Processing of APP by BACE1 to release Aβ is also affected by its neighboring secretases. ADAM10, as well as ADAM17 and ADAM9, are recognized as α-secretases and prevent Aβ formation by cleaving APP within the Aβ domain (mainly after Q16 and K17) [see reviews by (Allinson et al., 2004; Asai et al., 2003; Haass et al., 2012; Kuhn et al., 2010; Saftig and Lichtenthaler, 2015)]. BACE2 shares ~59% amino acid homology with BACE1, but it preferentially cleaves APP mainly between F19 and F20 and between F20 and A21 within the Aβ domain (Farzan et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2006; Yan et al., 2001). This is consistent with the observation that BACE1 deficiency almost abolishes the production of Aβ in mice (Cai et al., 2001; Luo et al., 2001; Roberds et al., 2001). An asparagine endopeptidase is suggested to function as a δ-secretase by cleaving APP at N373 and N585 residues, and this cleavage selectively enhances Aβ levels due to increased BACE1 accessing CTFδ fragments to initiate Aβ generation (Zhang et al., 2015).

As a protease, it is expected that BACE1 will have many cellular substrates. In addition to previously identified BACE1 substrates such as neuregulin-1 (Nrg1) (Fleck et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2006; Luo et al., 2011; Willem et al., 2006), voltage-gated channel proteins such as sodium channel protein β-subunits (Kim et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2005), the potassium channel proteins KCNE1 and 2 (Hitt et al., 2010; Sachse et al., 2013), neural cell adhesion molecule close homolog of L1 (Hitt et al., 2012; Kuhn et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2012), Notch ligands Jagged-1 and Jagged-2 (He et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2013), and contactin-2 (Gautam et al., 2014), many more membrane-bound proteins have now been identified as BACE1 substrates by unbiased proteomic or secretome approaches using BACE1-null mouse or zebrafish models (Hemming et al., 2009; Hogl et al., 2011; Hogl et al., 2013). By comparative proteomic analyses of wild-type vs. BACE1-null mouse cerebrospinal fluid samples, ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase 5, receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase N2, and plexin domain-containing 2 are the most recent additions to this substrate list (Dislich et al., 2015). Despite the identification of additional BACE1 substrates in recent years, the number of these substrates that is keenly dependent on BACE1 cleavage remains to be established in future studies. Thus far, cleavage of APP to release Aβ is still the major focus of BACE1 research because of continuing reports on the synaptic toxicity of Aβ.

Synapses and cognitive function

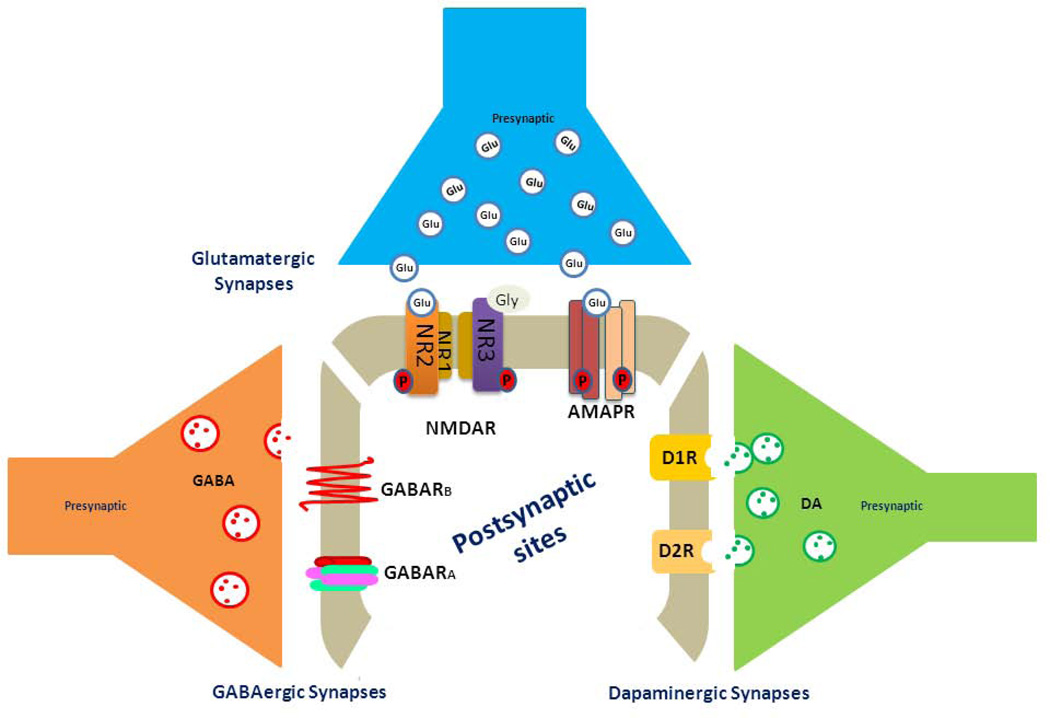

Synapses are interfaces that are formed by pre- (from the axonal terminus) and post-synaptic membranes (mostly from receiving dendrites or somata). Synapses mediate neuronal communications in the form of electronic or chemical transmission. Dysregulation of neuronal communications in the limbic system can lead to the progressive loss of learning and memory. Synaptic chemical transmissions occur when released presynaptic neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine or glutamate, bind to their receptors on the postsynaptic membrane to induce neuronal polarization and depolarization. Enhanced synaptic transmission translates to stronger synaptic strength; memory formation is highly related to long-term changes in synaptic strength, which is quantifiable by electrophysiological measures (Murphy and Corbett, 2009). Enhanced synaptic connections, i.e. by high-frequency stimulation, induce long-term potentiation (LTP), while reduced LTP is mostly correlated with impaired learning and memory. On the other hand, long-term depression (LTD) results from a weakening of synaptic connections. Although mechanisms of induction, expression, and maintenance of LTP and LTD are variable in different brain regions, it is widely accepted that LTP and LTD are common models for measuring synapse-specific changes required for memory formation. The control of synaptic strength is coordinately regulated by three types of synapses: glutamatergic, GABAergic, and dopaminergic (Figure 1). To understand the interconnected effects of Aβ on these synapses, we briefly outline structural organizations of these synapses, while more detailed molecular pathways underlying the formation and induction of these synapses are discussed elsewhere.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of three types of synapses.

Glutamate is an amino acid neurotransmitter and is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter at almost all glutamatergic synapses in the central nervous system. This molecule binds to multiple postsynaptic receptors, including the NMDA receptor (comprising two GluN1 subunits and two GluN2A, 2B, 2C or 2D subunits) and the AMPA receptor (a tetramer formed by two dimers of GluR1, GluR2 or two GluR5 subunits). GluN3 has high affinity for Gly, and it is possible to form a functional NMDA receptor containing GluN1, GluN2 and GluN3. Different combinations of these subunits in NMDA and AMPA receptors exhibit unique synaptic profiles. Synaptic vesicles releasing other neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine for synaptic transmission are not depicted in this figure. GABA is the chief inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system and plays a principal role in suppressing neuronal excitability throughout the nervous system. It mainly binds to 2 types of postsynaptic GABA receptors, GABAAR and GABABR. GABACR are closely related to GABAAR, although differences in their transmission have been identified but are not listed separately in this figure. GABAARs are usually a ligand-gated Cl channel formed by a pentamer, while GABABRs belong to the family of seven transmembrane G-coupled protein receptors. Dopamine (DA) is a neurotransmitter of the catecholamine and phenethylamine families that play a number of important roles in cognitive functions including cognitive control, arousal, and motivation. DA mainly binds to D1-like receptors (D1 and D5) and D2-like receptors (D2, D3, and D4).

i) Glutamatergic synapses

Glutamate is the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter in the nervous system. Functional glutamatergic synapses are critical for learning and memory and are composed of presynaptic glutamate stored within synaptic vesicles and postsynaptic glutamate receptors. In the hippocampus and cortex, glutamate released from pyramidal neurons binds to two types of glutamate receptors with channel-gating properties: the a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA)/kainate subtypes and the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) subtypes. At the molecular level, NMDA receptors (NMDARs) are transmembrane channel-forming heteromers assembled by the obligatory NR1 subunit (GluN1) and modulatory NR2/3 subunits (GluN2A, 2B, 2C and 2D for Glu binding; GluN3A and GluN3B for Gly binding) (Low and Wee, 2010; Nong et al., 2003; Stephenson, 2001). Upon glutamate binding, activated NMDA receptors permit Ca2+ influx and an instant rise in postsynaptic Ca2+ levels; higher levels induce LTP while moderate levels induce LTD (Kennedy and Ehlers, 2006). In hippocampal pyramidal neurons, ligand-gated NMDARs are predominant in evoking Ca2+ signals in postsynapses. Receptors containing different NR2 subunits generate different intensities and durations of Ca2+ currents. It is established that Ca2+ influx through NR2B–containing receptors is larger and longest-lasting compared to NR2A-containing receptors. Multiple Ser/Thr residues in the NR2 C-terminal domain undergo phosphorylation or dephosphorylation by PKA, the Ca2+-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), and protein phosphatase 1 for functional regulation (Coultrap and Bayer, 2012; Thomas and Huganir, 2004).

AMPA receptors (AMPARs) are both glutamate receptors and cation channels assembled as a heterotetramer, with two dimers from a combination of any of the five GluR subunits (GluR1 to GluR5) (Greger et al., 2007). Binding of glutamate to AMPARs induces the pore to quickly open and permit ion influx for depolarization. GluR2, which usually forms a dimer with the putative second membrane (M2) domain, also known as the re-entrant loop, is critical for regulating calcium permeability (Derkach et al., 2007). GluR2-lacking AMPARs are permeable to sodium, potassium, and calcium, while GluR2-containing AMPARs will almost always render the channel impermeable to calcium. GluR2 is post-transcriptionally regulated by RNA editing in M2; the Q- to R-editing with R in the channel site renders AMPARs unfavorable for calcium to enter the cell through the pore; GluR2 in the central nervous system is mostly in the R form. Hence, AMPA receptors containing the unedited form of GluR2Q have high Ca2+ permeability, while GluR2Rs have minimum Ca2+ conductance (Sommer et al., 1991).

AMPAR activation and depolarization also regulate intracellular transient or sustained Ca2+ currents by causing NMDARs to open their pores and to increase Ca2+ permeability. Compared to relatively stationary NMDARs, trafficking of AMPARs to dendrites and spines is a key step for the control of postsynaptic plasticity; LTP promotes recruitment of more AMPAs to postsynaptic membranes for long-lasting potentials (Malinow and Malenka, 2002). On the other hand, rapid lateral diffusion cycling of AMPARs, but not NMDARs, into and out of the synaptic membrane, followed by internalization, induces long-term depression (LTD), which can in turn cause endocytosis of NMDARs, shrinkage of dendritic spines, endocytosis of AMPARs, and synapse loss (Borgdorff and Choquet, 2002; Lau and Zukin, 2007). Multiple post-translational modifications regulate this trafficking. One common observation is that phosphorylation of GluR1 by PKA increases its surface expression (Carroll et al., 1998; Roche et al., 1996). Alternatively, clustering of Ca2+-sensitive CaMKII at synapses regulates AMPAR surface expression, while src/fyn kinase, PKC, and cdk5 also regulate trafficking of different AMPARs to control their activities (Anggono and Huganir, 2012; Wang et al., 2014). A recent study suggests that Aβ-mediated AMPAR loss is due to increased AMPAR ubiquitination, as down-regulation of the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-1, known to ubiquitinate AMPARs, prevents surface AMPAR loss and synaptic weakening (Rodrigues et al., 2016).

Although not illustrated in Figure 1, LTP induction at excitatory synapses is also modulated by another class of glutamate receptors, the metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) (Pin and Bockaert, 1995). Synaptic mGluRs are seven transmembrane, non-ionotrophic G-protein coupled receptors. The functional core signaling receptor appears to be a dimer, although monomeric mGluR is functional (El et al., 2012). The mGluR family has eight members; type I members (mGluR1 and mGluR5) are predominantly localized on the postsynaptic membrane, while members of types II and III are mainly localized on presynaptic membranes. All members except for mGluR6 are found in cortical and hippocampal neurons. The binding of glutamate to mGluR1 and mGluR5 on the excitatory postsynaptic membrane induces certain forms of LTP by increasing inflow of Ca2+ and potentiating NMDAR activity (Anwyl, 2009). In contrast, binding of glutamate to presynaptic mGluRs appears to inhibit NMDARs, resulting in the induction of LTD (Collingridge et al., 2010).

ii) GABAergic synapses

To avoid synaptic hyperexcitation, excitatory output of pyramidal neurons is precisely counterbalanced by input from inhibitory interneurons via binding of the presynaptically released neurotransmitter GABA (γ-Aminobutyric acid) to the GABA receptor on the postsynaptic membrane. In adult brain, GABAergic synapses are mainly inhibitory synapses, which are typically formed either on soma or dendrites from neurons classified as inhibitory interneurons (Freund and Katona, 2007; Fritschy et al., 2012; Kullmann and Lamsa, 2011). The structure and synaptic plasticity of GABAergic synapses vary based on the types of interconnected neurons and the postsynaptic locations (soma, proximal vs. terminal dendrites). Unlike excitatory synapses, which have postsynaptic spines serving as an organized compartment for sensing Ca2+ influx and for sustaining long-lasting synaptic plasticity, spines are often absent on inhibitory synapses formed by interneuronal dendrites. While hippocampal inhibitory synapses have been described in more detail by others (Caroni, 2015), we briefly summarize that synapses onto hippocampal principal cells are interconnected with parvalbumin-positive fast-spiking interneurons, which are the most abundant in the hippocampus, or non-fast-spiking somatostatin-or calbindin-positive interneurons, for two distinct orchestrations of synaptic networks.

At the molecular level, GABA receptors are distinguished by two subtypes: GABAA and GABAB receptors. GABAA receptors are ligand-activated chloride channels with the channel pore symmetrically assembled by five multi-transmembrane α, β, and γ subunits in various combinations (Barrera et al., 2008). Binding of GABA to this receptor quickly opens the pore to permit inflow of Cl− into the affected neuron, which results in more negative membrane potentials. The net effect is inhibitory or hyperpolarizing and makes it more difficult for neurons to produce synaptic transmission. GABAB receptors are G protein-coupled receptors, recognized as metabotropic receptors. GABA receptors, mainly GABAA receptors, are also abundantly localized on extrasynaptic zones, and binding of GABA to these extrasynaptic receptors in an autocrine manner will also modulate synaptic plasticity (Ferando and Mody, 2014).

iii) Dopaminergic synapses

Dopaminergic synapses, formed by presynaptic axonal termini from dopaminergic neurons and dendrites from pyramidal neurons or interneurons, play a key role in protein synthesis-dependent forms of synaptic plasticity (Bjorklund and Dunnett, 2007). Dopamine released from presynaptic vesicles of dopaminergic neurons binds to postsynaptic dopamine receptors, which are metabotropic G-protein coupled receptors and have two distinct subfamilies (D1-like and D2-like). In the hippocampus and cortex, dopamine D1-like receptors (D1R; D1 and D5) are the predominant dopamine receptors on pyramidal neurons. D1 receptors are especially abundant in dendritic spines, whereas D5 receptors are present on dendritic shafts at excitatory glutamate synapses, but also at presynaptic spine-targeting varicosities (Bergson et al., 1995). Activated D1R in glutamatergic postsynapses triggers the D1R-coupled adenylyl cyclase to produce cyclic adenosine monophosphatase (cAMP) and to activate the downstream molecules protein kinase A (PKA), cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB), and DARPP-32, which is a small protein expressed in dopaminoceptive spiny neurons and acts as a potent inhibitor of protein phosphatase-1. While dopaminergic synapses are known to mediate various brain psychiatric or motor functions, this sequential cascade arising from D1R activation can also modulate LTP. It has been shown that D1R activation can lead to an increase in surface expression of AMPA and NMDA receptors by modulating NMDAR-dependent synaptic plasticity (Gao and Wolf, 2007; Gao and Wolf, 2008; Smith et al., 2005). Either dopamine insufficiency, such as in aging, or dopamine hyperactivity, as in acute stress, will lead to impairments in working memory, which can be ameliorated by treatment with D1 receptor agonists or antagonists. The dopamine D2-like receptors (D2R) are expressed presynaptically at inhibitory axon terminals, postsynaptically at excitatory and inhibitory synapses, as well as presynaptically at dopaminergic axon terminals (Fitzgerald et al., 2012; Negyessy and Goldman-Rakic, 2005; Pinto and Sesack, 2008). Depending on the localization of these receptors, D2R signaling maintains the cortical excitatory-inhibitory balance by downregulating cAMP signaling. For example, dopaminergic modulation of early LTP in hippocampal CA1 requires NMDARs containing NR2B subunits via D4Rs (Herwerth et al., 2012). At glutamatergic synapses on interneurons, the activation of postsynaptic D4R, a typical member of the D2R family, reduces the excitation of interneurons by modulating AMPA receptor trafficking (Yuen et al., 2010). At glutamatergic synapses on pyramidal neurons, the activation of postsynaptic D4R enhances pyramidal neuron excitation by promoting phosphorylation of the GluR1 subunit of AMAPRs by the pyramidal neuron-specific kinase αCaMKII. In contrast, at inhibitory synapses on pyramidal neurons, stimulation of postsynaptic D4Rs reduces inhibitory currents in pyramidal neurons by reducing surface expression of GABAA receptor β2/3 subunits in an actin-dependent manner. Hence, coordinated signaling actions among glutamatergic and dopaminergic synapses are essential for synaptic plasticity and proper cognitive functions.

Aβ and synaptic functions

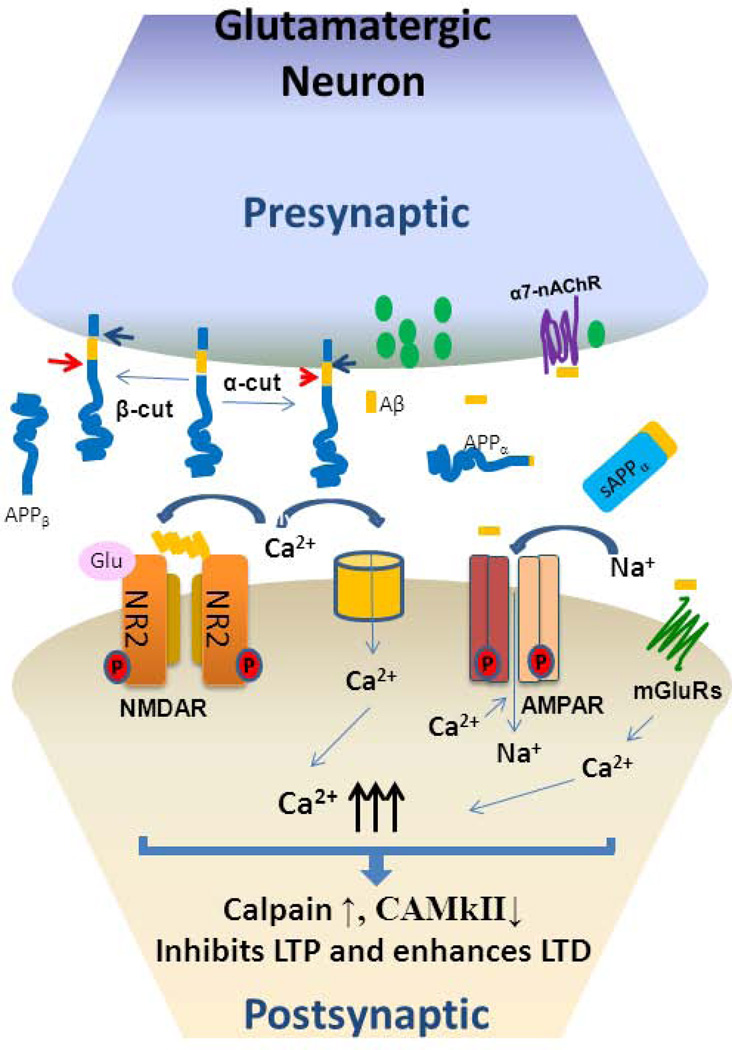

By using biochemical and electron microscopy approaches, the protein components for Aβ generation, such as APP (Vassar and Zheng, 2014), BACE1 (Buggia-Prevot and Thinakaran, 2015), and γ-secretase (DeBoer et al., 2014; Haass et al., 2012), have all been found in the presynaptic site and Aβ can be released locally to impact postsynaptic functions (Figure 2). The lumen of presynaptic vesicles is acidic (pH=5.6), which is compatible with favored BACE1 processing under moderate acidic conditions. Processing of APP in presynaptic vesicles by BACE1 will locally release sAPPβ and APP C-terminal fragment (C99), which will be cleaved by γ-secretase to release Aβ. BACE1 activity is elevated in AD brains and BACE1-cleaved sAPPβ and Aβ are correspondingly increased. sAPPβ appears to have no measurable effect on LTP or LTD (Chasseigneaux and Allinquant, 2012), but Aβ peptides, especially containing the more readily aggregated Aβ42, do have pathophysiological impacts on synaptic function.

Figure 2. Soluble Aβ in synaptic dysfunction.

Presynaptically expressed APP is cleaved by α-secretase (arrowhead) to release sAPPα and α-C-terminal fragment (αCTF), which is further cleaved by γ-secretase (blue arrow) to generate P83 and intracellular domain of APP (AICD). APP cleaved by BACE1 (red arrow) releases sAPPβ and βCTF, which is further cleaved by γ-secretase to generate Aβ and AICD. Pathological levels of Aβ are found to interact with NMDA receptors, which are voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and such binding blocks Ca2+ flow. AMPA receptors regulate the exchange of Na+ or K+ via ligand-gated control. The increase in cytosolic Ca2+ leads to decreased LTP and increased LTD. In addition to the direct effects on NMDAR and AMPAR proteins, Aβ oligomers are also suggested to form annular amyloid pores, which alter the membrane dielectric barrier and allow influx of Ca2+. Aβ oligomers mediate release of glutamate from synaptic vesicles through binding to presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing α7 subunits (α7-nAChRs).

At the physiological level, Aβ generated at synapses in response to evoked activity of hippocampal neurons suppresses synaptic activity to avoid excitotoxicity (Kamenetz et al., 2003). Suppressed Aβ generation by γ secretase inhibition is sufficient to increase EPSC frequency (Kamenetz et al., 2003). Recording synaptic transfers at single presynaptic terminals and synaptic connections using rodent hippocampal cultures and slices shows that endogenous level of Aβ boosts ongoing activity in the hippocampal network and is required for short-term synaptic facilitation during bursts in excitatory synaptic connections (Abramov et al., 2009). Rodent hippocampal slice recording experiments also show that Aβ42 facilitates induction and maintenance of long term potentiation, whereas treatment with Aβ antibodies inhibits hippocampal LTP (Morley et al., 2010). Consistent with these findings, the addition of human Aβ42 to mice treated with Aβ antibody and siRNA against murine APP reverses impaired learning and memory behaviors in mice and reduced LTP, suggesting that endogenously produced Aβ is needed for normal LTP and memory function (Puzzo et al., 2011).

In AD brains, accumulated Aβ is regionally selective, with particularly high concentrations found in frontal cortex, entorhinal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and parietal association cortex (Braak and Braak, 1991). Reportedly, abnormal accumulation of Aβ in the form of dimers, trimers, or oligomers in the synaptic cleft is highly correlated with memory-related synaptic dysfunctions in AD (Haass and Selkoe, 2007; Palop and Mucke, 2010; Sheng et al., 2012). In short, various toxic forms of Aβ have gained broad attention for impairing LTP and facilitating LTD. AD is thus recognized as a disease of synaptic failure (Selkoe, 2002; Spires-Jones and Hyman, 2014; Tu et al., 2014; Westmark, 2013).

i) Aβ in glutamatergic synapses

Pathological levels of Aβ impair NMDA-dependent synaptic plasticity, mainly by inducing desensitization of NMDARs in synapses to inhibit LTP and by enhancing LTD through extrasynaptic NMDA-dependent and -independent signaling pathways (Bezprozvanny and Hiesinger, 2013; Li et al., 2009; Li et al., 2011; Minano-Molina et al., 2011; Walsh et al., 2002). Aβ, mainly in soluble multimers or oligomers, directly interacts with NMDARs in pathophysiological conditions (Lacor et al., 2007; Shankar et al., 2007). In wild-type cultured cortical neurons, treatment with either synthetic Aβ42 peptides or naturally secreted Aβ from transgenic mice overexpressing Swedish mutant APP (K670N/M671L mutation) promotes endocytosis of surface NMDARs; the reduction of surface NMDARs depresses NMDAR-dependent Ca2+ currents (Snyder EM et al., 2005). One study suggests that inhibition of N-cadherin cleavage by Aβ treatment causes the enhanced endocytosis of NMDARs (Uemura et al., 2007), but another study indicates that dephosphorylation of p-Tyr1472 in the NR2B subunit by Aβ-induced STEP61, a protein tyrosine phosphatase enriched in the postsynaptic terminal, decreases NMDARs on synaptic membranes (Kurup et al., 2010). Relatedly, STEP61 is progressively increased in the cortex of Tg2576 mice over the first year, as well as in prefrontal cortex of human AD brains. Activation of insulin signaling, on the other hand, appears to downregulate binding of Aβ to NMDARs and thus blocks synaptic impairments (De Felice et al., 2009).

Aβ can also significantly impair synaptic plasticity by directly decreasing the availability of AMPARs at excitatory synapses. Surface levels of AMPARs, which are the major excitatory neurotransmitter receptors in the brain, are directly correlated with synaptic strength; recruiting new AMPARs to the surface increases LTP, while reducing AMPARs via internalization promotes LTD (Malenka and Malinow, 2011). Surface levels of GluR1 are dependent on PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Ser845, as mice lacking phosphorylation on GluR1 S845 exhibit LTP deficits (Lee et al., 2003). It has been further shown that cultured wild-type neurons treated with Aβ oligomers have reduced GluR1 levels on the surface due to decreased levels of GluR1 p-Ser845 and increased dephosphorylation by calcium influx–activated calcineurin (Minano-Molina et al., 2011). Studies using cultured Tg2576 APP mutant neurons show clear reductions in GluR1 and its interacting downstream molecule postsynaptic density-95 (PSD-95), and these reductions can be blocked by reduced Aβ generation (Almeida et al., 2005).

Soluble Aβ oligomers also affect trafficking of other GluR subunits. For example, surface levels of GluR2 are decreased by Aβ treatments and the concentration of free cytosolic Ca2+ is therefore increased due to reduced Ca2+ extrusion and sequestration in hippocampal neurons (Hsieh et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2010). If locally produced Aβ is accumulated and laterally forms Aβ oligomers, it will induce clustering of the postsynaptic GluR5 and elevation of intracellular Ca2+, thereby causing synapse reduction (Renner et al., 2010). Hence, Aβ peptides suppress synaptic strength by downregulation of both AMPAR and NMDAR function via controlling intracellular Ca2+ currents. Decreased AMPAR surface expression, with any combination of GluRs, can cause loss of dendritic spines, which likely leads to increased endocytosis of synaptic NMDA receptors and reduced synaptic responses (Malenka and Malinow, 2011). On the other hand, reduced NMDAR activity facilitates Aβ generation, which will exacerbate synaptic toxicity, although the mechanism is not fully understood (Sheng et al., 2012).

Soluble Aβ also impairs synaptic plasticity through group I mGluRs (mGluR1 and 5). By weak low-frequency stimulation, oligomeric Aβ can bind to mGluR1/5 to induce Aβ-mediated synaptic depression (promoting LTD) and blockage of LTP (Chen et al., 2013; Kessels et al., 2013; Rammes et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2004). It has been suggested that mGluR5 may act as a scaffold for Aβ binding, perhaps through a complex with cellular prion protein (PrP), as the extracellular domain of mGluR5 interacts with both PrP and Aβ42 and this binding results in the activation of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (Hamilton et al., 2015; Lauren et al., 2009). Blocking PrP function by anti-PrP reduces Aβ-mediated LTP impairments (Barry et al., 2011; Lauren et al., 2009). The compound glimepiride, a sulphonylurea approved for the treatment of diabetes mellitus, can reduce surface level of PrP by increased releasing of soluble PrP from neurons and may protect against Aβ-induced synapse damage by reducing Aβ-Prp interaction occurred within membrane micro-environments (Osborne et al., 2016). Intriguingly, others have failed to replicate the role of PrP in Aβ-induced synaptic depression, reduction in spine density, or blockade of LTP, regardless of whether PrP was overexpressed or ablated (Balducci et al., 2010; Calella et al., 2010; Kessels et al., 2010), arguing against a critical role of PrP as a coupling receptor.

Smaller forms of soluble Aβ, Aβ dimers or trimers, are naturally extracted from AD brains and can induce LTD by favorably acting through mGluR1 (Davis et al., 2011; Shankar et al., 2008). Postsynaptic GluN2B-containing NMDARs are essential for excitotoxicity, functioning as extracellular "death receptors". Binding of Aβ to mGluR1/5 causes a selective loss of synaptic GluN2B responses by switching GluN2B-containing NMDARs to GluN2A-containing NMDARs, a process leading to LTD, and this process is likely related to sequential stimulation of downstream kinases such as JNK, Cdk5, and p38 MAPK in response to mGluR activation.

Most recently, a role for group II mGluRs in reducing Aβ oligomer-mediated synaptic disruption has begun to gain attention. When transgenic mice that accumulate Dutch amyloid-β (Aβ) oligomers are chronically treated with BCI-838, an antagonist of Group II mGluRs, they show improved learning and reduced anxiety (Kim et al., 2014). Activation of Group II mGluRs by agonist DCG-IV, on the other hand, induces Aβ42 generation (Kim et al., 2010). Activation of mGluR7, a member of group III mGluRs, reduces NMDAR currents in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons, which are selectively impaired by soluble Aβ (Gu et al., 2014). This effect is more related to the altered surface expression of NR1, but not NR2B, via regulation of F-actin and by increases in p21-activated kinase (PAK)-mediated cofilin phosphorylation. Hence, all three groups of mGluRs are participating in Aβ-mediated synaptic impairments.

While the activity of glutamate receptors in synapses is important for LTP, soluble Aβ oligomers at low nanomolar levels induce excessive activity of NMDARs at extrasynaptic sites by high frequency stimulation (Kervern et al., 2012; Li et al., 2011). The pool of extrasynaptic GluN2B-containing NMDARs is a major target of Aβ oligomers in the hippocampus. It is likely that Aβ promotes release of glutamate from astrocytes, rather than solely from synaptic vesicles, which in turn activates extrasynaptic NMDA receptors on neurons (Talantova et al., 2013). Polyamines, such as spermidine and spermine, are positive modulators of NMDAR function and specific inhibition of de novo polyamine synthesis has been shown to block Aβ-mediated activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors (Gomes et al., 2014).

In addition to the direct effects on glutamate receptors, Aβ is also suggested to mediate the release of synaptic vesicles. Physiologically released Aβ binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing α7 subunits (α7-nAChRs) localized on the presynaptic zones and this binding promotes activity-dependent regulation of synaptic vesicle release (Abramov et al., 2009). However, others have shown that naturally secreted soluble Aβ, such as trimers, has no effect on presynaptic vesicle release but is potent in reducing LTP (Townsend et al., 2006). Nevertheless, presynaptic microinjection, but not extraneuronal perfusion, of 10–100 nM Aβ42 oligomers depletes the docked synaptic vesicle pool after high-frequency presynaptic stimulation and impairs synaptic transmission (Moreno et al., 2009). Normal P/Q- or N-type Ca2+ channels are high-voltage-gated calcium channels contributing to vesicle release at synaptic terminals and therefore are critical for synaptic stability; increasing N- and P/Q-type calcium currents triggers synaptic vesicle release. A recent study reported that as low as 8 nM of Aβ42 globulomer (a highly stable globular oligomeric Aβ) can impair LTP by directly reducing the threshold for channel opening of presynaptic P/Q- or N-type Ca2+ channels (Hermann et al., 2013; Mezler et al., 2012; Nimmrich et al., 2008). Specifically blocking P/Q-type or N-type calcium channels with peptide toxins completely reversed Aβ globulomer-induced deficits in glutamatergic neurotransmission. Consequently, an increase in Ca2+ current at presynaptic terminals triggers vesicle release and excitotoxicity in AD brains. Enhanced presynaptic Ca2+, on the other hand, facilitates calpain activation by increased degradation of dynamin, a protein critical for synaptic vesicle endocytosis, and depletion of dynamin interrupts synaptic vesicle recycling (Kelly and Ferreira, 2006; Kelly et al., 2005; Watanabe et al., 2010). Alternatively, Aβ42, as low as 50 nM, may disrupt the formation of synaptophysin and VAMP2 complex, followed by increasing the amount of primed vesicles and exocytosis (Russell et al., 2012), although the precise mechanism for this interaction is not yet clear.

Collectively, all of these aspects point to a central culprit: abnormally and sustained high pre- and postsynaptic Ca2+ by soluble Aβ. This abnormal calcium homeostasis can alter the function of many Ca2+-dependent proteins such as CaMKII, calcineurin, and calpain. Activated calpain in postsynaptic regions will also promote LTD by degrading NMDARs and their downstream PSD-95 at glutamatergic synapses (Dong et al., 2004; Li et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2000; Roselli et al., 2005; Vinade et al., 2001). On the hand other hand, Aβ-mediated impairments in glutamatergic synapses are far more complicated and multidimensional than a single “Ca2+ hypothesis”. Thus, it is not practical to target any specific signal receptor molecule for blocking synapto-toxic effects of Aβ.

ii) Aβ in GABAergic synapses

Comparatively speaking, the effect of Aβ on inhibitory synapses has been less intensively studied, partially because GABAergic synapses were not initially thought to be as affected in AD. More recent studies, however, have shown direct effects of Aβ on inhibitory interneurons (Palop and Mucke, 2010). The reduction of GABA functions in AD patients is related to high levels of soluble Aβ, which can decrease bursting activity and late inhibitory potentials of GABAergic neurons in the septohippocampal system (Nava-Mesa et al., 2014). Autoradiography studies show significant reductions in both GABAA and GABAB receptors in AD postmortem stratum moleculare of the dentate gyrus, stratum lacunosum-moleculare, and stratum pyramidale of CA1 (Chu et al., 1987a; Chu et al., 1987b). Extended studies indicate that GABAB receptor subunit R1 expression is stable or increased, but is decreased as in the late Braak disease stage (Iwakiri et al., 2005). These observations are further validated by studies in animal models.

In AD PS1/APP J20 mouse dentate gyrus, aberrant overexcitation is linked to high levels of Aβ, which sensitizes at least some neuronal networks due to disrupted GABA function (Palop et al., 2007). Others observed selected loss of hippocampal calretinin-positive interneurons in a PS1/APP model from 2 to 12 months of age, and this subpopulation plays a crucial role in controlling other interneurons through synchronous rhythmic activity in the hippocampus (Baglietto-Vargas et al., 2010). It has been shown that hippocampal Aβ injections in rat are sufficient to induce reductions in GABAergic input to the hippocampus and to exhibit aberrant θ oscillations (Villette et al., 2010). In a separate study of the fimbria-CA3 complex postsynaptic response, Aβ also induces a significant decrease in late inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) (Nava-Mesa et al., 2013). Treatment of somatosensory neurons with soluble Aβ as much as 1 µM has also been found to decrease agonist-evoked GABAA responses and to depress monosynaptic GABAA receptor-mediated IPSCs to 60% of control levels on average, whereas a reversed sequence control peptide is ineffective (Ulrich, 2015). The downregulated GABAA receptors for Aβ-mediated synaptic inhibition are due to increased endocytosis of GABAA receptors, because the induced IPSC decline was prevented by intracellular applications of p4, a peptide inhibitor to block the dynamin-mediated removal of GABAA receptors from the plasma membrane. Others indicate that Aβ treatment in brain slices reduces conductance in G-protein-coupled inward rectifier potassium (GirK), which is a specific downstream effector coupled with the GABAB receptor. Relatedly, deficiency or mutations in Girk channels, particularly the GIRK2 subunit, reduce LTP and increase LTD in hippocampus (Luscher and Slesinger, 2010).

Taken together, Aβ-mediated GABA dysfunction therefore can disrupt synaptic and cognitive deficits in AD patients by deregulating excitatory/inhibitory balances, rather than neurodegeneration, through both types of receptors. Nevertheless, alternative mechanisms may be related to disruption of GABAergic interneuron functions by desensitizing α7β2-nAChRs (Liu et al., 2012). GABAergic interneurons in the CA1 subregion abundantly express α7β2-nAChRs, and as low as 1 nM oligomeric Aβ is sufficient to disrupt 10 mM choline-elicited cholinergic signaling in hippocampal GABAergic interneurons via interactions with α7β2-nAChRs. This inhibition may cause acute disruption of cholinergic signaling on interneurons and hyper-excite principal cell types (e.g., pyramidal cells), leading to synaptic deficits.

iii) Aβ in dopaminergic synapses

Studies involving dopaminergic synapses in AD synaptic failure date back to the early 1980s, with reports that DA levels in post-mortem brain tissues of AD patients were decreased and that DA receptor distribution and density in several brain structures of the temporal lobe were altered (Martorana and Koch, 2014). Although dopaminergic synaptic dysfunction is more studied in Parkinson’s disease and a direct role of DA in AD pathogenesis is debatable, the presence of extrapyramidal signs, attributable to nigrostriatal dysfunction in approximately 35–40% of AD patients, supports a contribution of DA-containing neurons to AD cognitive dysfunctions (Lopez et al., 1997). In transgenic mice overexpressing Swedish APP and PS1ΔE9, protein levels of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), specifically from nigral dopamine neurons, are age-dependently increased (Perez et al., 2005). Moreover, TH-positive dystrophic neurites with rosette or grape-like cluster dispositions are found near amyloid plaques, indicating that dopaminergic pathology and amyloid deposition are closely interconnected, but that it is likely a downstream event of the Aβ insult. In AD mouse models, the dopamine metabolite DOPAC is significantly reduced in the striatum, further suggesting a causative role for Aβ on dopamine dysfunction. Strikingly, AD mouse models treated with either the dopamine precursor levodopa (Ambree et al., 2009), the dopamine reuptake blocker nomifensine (Guzman-Ramos et al., 2012), or even the dopamine receptor agonist apomorphine (Himeno et al., 2011) showed rescued Aβ-mediated impairments in memory and learning. However, dopamine toxicity can also in turn impair learning and memory. In an effort to determine an active effect of striatal dopamine on AD pathology, the neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) was injected into APPSWE/PS1E9 mice (Melief et al., 2015). The treated mice displayed significant impairments in Barnes maze performance at an early age and worsened behavioral flexibility in a task-switch phase of the water maze at older ages when compared to controls.

In AD patients, reduced DA functions, due to dramatically reduced expressions of both D1R and D2R, as well as DAT and TH, are found mainly in prefrontal cortex and hippocampus (Allard et al., 1990; Cross et al., 1984; Joyce et al., 1998; Kemppainen et al., 2003; Kumar and Patel, 2007; Murray et al., 1995; Rinne et al., 1986a; Rinne et al., 1986b). Quantitative real-time PCR further confirmed overall reduced gene expression of all DA receptors (D1R–D5R) in the temporal lobe of AD patients (Gahete et al., 2010). The use of dopaminergic drugs, in particular of the DA-D2-agonist rotigotine, exhibits beneficial effects on some cognitive domains in AD patients (Koch et al., 2014). Giving rotigotine to AD patients also revealed unexpected changes in both increased cortical excitability and restored central cholinergic transmission (Martorana A et al., 2011).

Despite these encouraging results, maintaining physiological levels of dopamine appears to be more beneficial to synaptic functions. In an in vivo microdialysis experiment to measure the release of dopamine in prefrontal cortex of freely moving mice, perfusion with soluble 100nM of Aβ42 evoked a significant release of dopamine (to approximately 170% of basal levels) (Wu et al., 2007). Such stimulated DA is mediated by presynaptic α7-nAChRs, to which oligomeric Aβ will bind. In AD and in mouse models, Aβ also up-regulates nAChRs, and this forward feeding effect induces excessive efflux of dopamine and likely leads to synaptic depression by long-term dopamine depletion. Results from this study imply that overstimulating dopamine release is likely detrimental.

At the molecular mechanistic level, Aβ-induced presynaptic calpain activation is sufficient to mediate cleavage of the dopamine- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein 32 kDa (DARPP-32) at Thr153 (Cho et al., 2015). This enhances cleavage of DARPP-32, a key inhibitor of protein phosphate-1 (PP-1), which regulates phosphorylation levels of CREB. CREB is a transcription factor that functions as a molecular switcher by converting short-term to long-term memory (Kandel, 2012).

On the other hand, the beneficial effects of optimal levels of dopamine are likely to mediate stimulation of D1/D5 receptors by facilitating the insertion of AMPARs into the plasma membrane. It has been shown that D1/D5 receptor activation induces PKA phosphorylation of Ser845 in AMPAR subunit GluR1 (Gao and Wolf, 2007; Smith et al., 2005). Treatment with SKF81297, a selective D1/D5 receptor agonist, shows reversal of Aβ-induced removal of AMPARs and NMDARs from the dendrites in cultured hippocampal neurons and prevents Aβ-induced impairment of LTP in hippocampal slices (Jurgensen et al., 2011). Another D1/D5R receptor agonist, SKF38393, activates Src-family tyrosine kinases, but not protein kinase A or phospholipase C pathways, and protects LTP of hippocampal CA1 synapses from oligomeric Aβ-induced deleterious synaptic actions (Yuan et al., 2016). Hence, a body of evidence suggests that optimizing DA in the striatum or prefrontal cortex, as well as maintaining normal dopamine signaling function, is beneficial to cognitive functions in AD.

Inhibiting BACE1 to benefit synaptic function

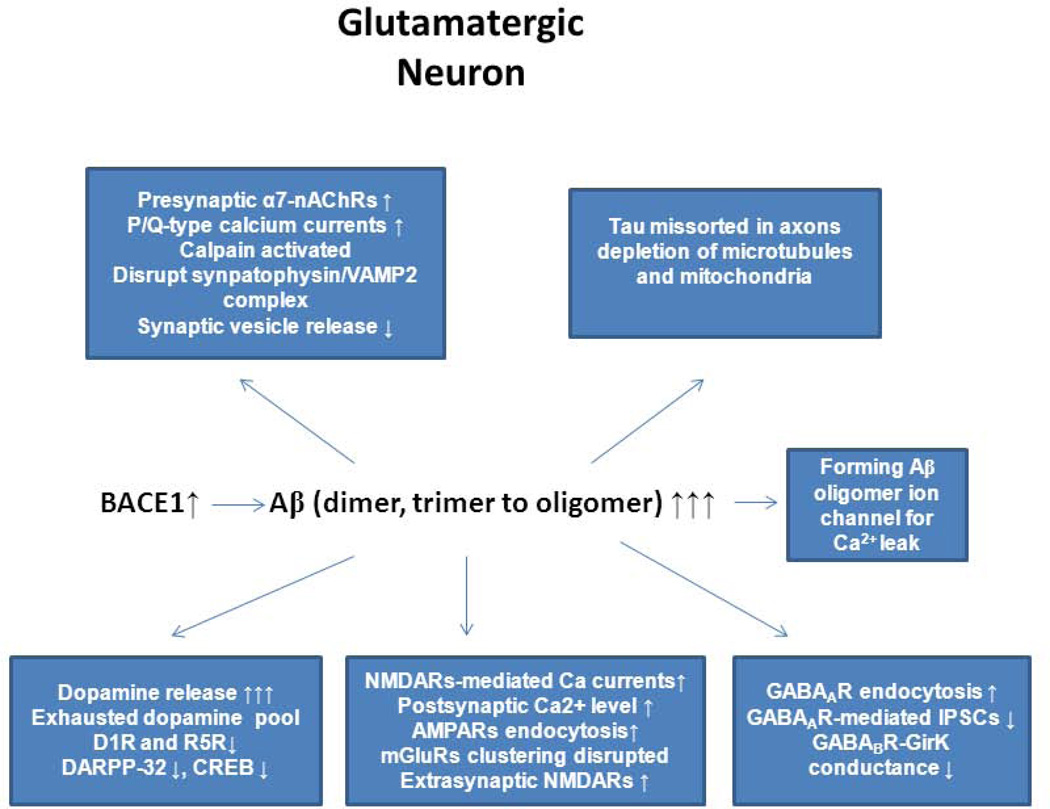

As outlined above, pathological levels of Aβ can disrupt synaptic functions by interacting with multiple cellular receptor proteins present in the pre- or post-synaptic glutamatergic, GABAergic, and dopaminergic synaptic membranes (Figure 3). Thus, substantial and long-lasting benefits for AD patients are unlikely to derive from targeting any one single synaptic system. While strategies for enhancing Aβ-degradation enzymes (Miners et al., 2008), clearance of Aβ by immunotherapy (Lemere, 2013), or chemical blocking of Aβ oligomerization (Klein, 2013) have been pursued, targeting reduced Aβ generation would be a more straightforward strategy for reducing Aβ-mediated synaptic toxicity. With increasing understanding of the toxic effects of γ-secretase inhibition, blocking BACE1 activity has emerged as the most promising approach for this purpose.

Figure 3. Impairments of Aβ on presynaptic and postsynaptic compartments.

In Alzheimer’s brains, BACE1 levels are elevated, which will cause production of pathological level of Aβ, in the form of dimers, trimers, or various sizes of oligomers. We summarize the impacts of toxic Aβ on all possible routes based on reports in the literature. Changes in downstream signaling molecules such as PKA and CaMKII in response to disrupted glutamatergic, dopaminergic, and GABAergic synapses are omitted.

First, BACE1 is the initiating enzyme for Aβ generation, and its inhibition will significantly reduce total Aβ. In BACE1-null mice, Aβ generation is almost abolished, and significant reductions in Aβ are seen in BACE1 heterozygous mice (McConlogue et al., 2007). Based on these mouse data, potent inhibition of BACE1 activity in humans is expected to decrease Aβ generation and Aβ oligomerization. Several pharmaceutical and biotech companies have therefore developed potent brain-penetrable BACE1 inhibitors that are being tested at various stages of clinical trials [see review by (Yan and Vassar, 2014a)]. The brain-penetrable BACE1 inhibitor GRL-8234 showed a rapid decrease in soluble Aβ in the brain of Tg-2576 mice, and long-term treatment up to 7.5 months rescued cognitive defects induced by Aβ in this mouse model (Chang et al., 2011). Once-daily injection of an improved BACE1 inhibitor, GRL-8234, for 2 months showed clear improvements in memory tests in 5xFAD AD mice (Devi et al., 2015). A six-month treatment regimen of Tg-2576 mice with another BACE1 inhibitor, TAK70, also showed decreased cerebral Aβ deposition by approximately 60% and ameliorated memory deficits (Fukumoto et al., 2010). Even a potent non-brain-penetrant BACE1 inhibitor, delivered directly into the brain using intracerebroventricular infusion in aged transgenic Tg-2576 mice, has been shown to reverse learning and memory deficits (Thakker et al., 2015). Several other potent BACE1 inhibitors such as AZD3839 (Jeppsson et al., 2012), AZ-4217 (Eketjall et al., 2013), and LY2811376 (May et al., 2011) have all been shown to dramatically reduce cerebral Aβ levels in animal models, despite lacking rigorous cognitive tests.

BACE1 inhibitors are currently under clinical trials aiming at treating patients with AD (Yan and Vassar, 2014b). The compound from Merck has shown potent inhibition and safety profiles in phase I trials and is currently in phase II and III combined trials [Forman et al., 2012]. Several other companies have also shown great promise with their BACE1 inhibitors in phase I trials. There is great hope that such a BACE1 inhibitor will prevent or reverse cognitive decline in AD patients. Consistent with this, a previous study showed that preventing the formation of Aβ oligomers by either increasing Aβ degradation or reducing Aβ generation reverses impairments of hippocampal LTP (Walsh et al., 2002). Hence, inhibiting BACE1 activity should be beneficial to AD patients.

Despite BACE1 inhibitors having great promise for AD therapy, potential side effects due to long-term dramatic reductions in BACE1 must be considered. Mice with complete deficiency of BACE1 exhibit certain cognitive deficits, as demonstrated in behavioral and electrophysiological experiments [see review by (Yan and Vassar, 2014a)]. These potential side effects are likely due to the required processing of BACE1 substrates, including highly important signaling molecules for normal brain functions such as neuregulin-1, sodium channel β-subunit, CHL-1, and Jag1. Interestingly, even lower levels of Aβ are considered to be essential for optimal CA1 LTP and learning by its binding to α7-nAChRs (Abramov et al., 2009). Fortunately, drug developers are aware of these potential side effects. A non-clinically developed BACE1 inhibitor tertiary carbinamine-1 shows minimal disruption of neuregulin-1 signaling activity while dramatically reducing brain Aβ (Sankaranarayanan et al., 2008). Such a careful strategy in human applications of BACE1 inhibitors will be necessary, and proper dosage of BACE1 inhibition should improve cognitive functions in AD patients without generating significant negative side effects.

Summary

Pathological levels of Aβ, in the form of dimers up to soluble oligomers, directly interact with NMDARs and induce endocytosis of NMDARs, which disrupts NMDAR-dependent Ca2+ currents. Altered Ca2+ homeostasis due to influx of Ca2+ may also arise from ion-specific permeable channels assembled by small Aβ oligomers (Jang et al., 2008). A rapid and sustained increase in intracellular Ca2+ leads to changes in downstream signaling molecules such as PKA, calcineurin, and CaMKII, which collectively regulate the surface expression of AMPARs. Reduced surface AMPARs decrease LTP and increase LTD, which can also be alternatively affected through mGluR clustering or binding to α7-nACRs. Hence, increased intracellular Ca2+ levels in postsynaptic dendrites and dendritic spines cause synapse impairments and spine loss. As discussed above, soluble toxic Aβ disrupts dopamine and GABA functions and contributes to synaptic dysfunction. In addition to direct effects on synaptic functions, Aβ-mediated increases in intracellular Ca2+ either in pre- or postsynaptic zones cause activation of calpain, which can lead to activation of cdk5 for Tau hyperphosphorylation and mis-sorting of endogenous Tau into dendrites, as well as pronounced depletion of microtubules and mitochondria (Frandemiche et al., 2014; Zempel et al., 2010). This cross-talk, mainly from Aβ42 (Hu et al., 2014), potentially further induces tau pathology in AD brains, as discussed in recent reviews (Bloom, 2014; Spires-Jones and Hyman, 2014; Stancu et al., 2014). Hence, Aβ-mediated synaptic toxicity has more far-reaching effects than just synaptic proteins.

Because of these collective findings, the benefits of BACE1 inhibition in reducing Aβ generation from APP have been well-received and have driven a series of reports in clinical trials. Challenges also stem from multiple aspects. First, APP appears to be cleaved by another protease at a site upstream of the BACE1 site, and this coupled with γ-secretase cleavage releases an 8 kDa sodium dodecyl sulfate stable fragment; BACE1 inhibition appears to increase this product (Portelius et al., 2013; Welzel et al., 2014). Although distinct from the toxic Aβ, this longer Aβ-containing peptide can still impair synaptic plasticity (Welzel et al., 2014). A more detailed elucidation is from Willem et al., who refer this cleavage as η-secretase, which possesses membrane-bound matrix metalloproteinase activity and cleaves APP695 between residues 504–505 (Willem et al., 2015). The η-secretase-cleaved C-terminal fragment (CTFη) is about 8 kDa, and CTFη was shown to be further processed by both α-secretase and BACE1 to release long and short Aη peptides (termed Aη-α and Aη-β) by using unique antibodies recognizing the specifically cleaved neoeiptopes (Willem et al., 2015). Recombinant or synthetic Aη-α was shown to inhibit long-term potentiation and to decrease hippocampal neuronal activity. Upon BACE1 inhibition, levels of Aη-α peptide will be elevated and this may compromise the reducing effect from Aβ oligomers.

Another challenge is the possible effects of BACE1 inhibition on its growing list of natural substrates (Dislich et al., 2015). BACE1-null mice show schizophrenia-like behaviors, age-dependent neurodegeneration, and impaired cognitive functions (Vassar et al., 2014; Yan and Vassar, 2014b). It is suggested that these phenotypes are partly attributed to neuregulin-1 (Nrg1) signaling, which is known to regulate various brain functions through its actions on glutamatergic, GABAergic, and dopaminergic synapses [see updated review in (Mei and Nave, 2014) for more detailed discussion on the role of Nrg1 in synaptic function]. BACE1-dependent Nrg1 signaling is required for normal myelination during development, remyelination after injury, and maintenance of muscle spindles [see recent review by (Fleck et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2015)]. Impaired neuronal migration is due to abrogated cleavage of Sema3A-mediated CHL1 cleavage by BACE1 (Barao et al., 2015; Hitt et al., 2012; Kuhn et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2012). Jag-Notch signaling pathway is important for synaptic function through the control of neurogenesis and brain development [see additional reviews by (Ables et al., 2011; Costa et al., 2003; Marathe and Alberi, 2015)]. BACE1 deficiency reduces neurogenesis by abolished cleavage of Jagged-1 and enhances Notch-mediated neurogenesis (Hu et al., 2013). Hence, complete inhibition of BACE1 is necessary to assess potential changes in these functions.

While these observations complicate the beneficial effects of inhibition of BACE1 on synaptic functions, APP is actually mostly cleaved by α-secretase, which cleaves APP within the Aβ region (Robakis et al., 1993; Sisodia et al., 1990). Increasing proteolytic activity of α-secretase is an alternative approach to decrease the release of toxic Aβ. Although the sAPPβ fragment has no definite effect on synaptic function, the α-secretase-cleaved sAPPα fragment has been shown to promote neurogenesis and increase LTP (Chasseigneaux and Allinquant, 2012). It should also be noted that all BACE1 substrates are alternatively cleaved by α-secretase, and this double processing is likely to ameliorate the side effects arising from complete ablation of BACE1 activity; this may also explain the relatively mild phenotypes seen in BACE1-null mice (Cai et al., 2001; Luo et al., 2001; Roberds et al., 2001). Weighing all of these benefits against potential side effects associated with complete elimination of BACE1 activity, we conclude that strong reduction of BACE1 activity, especially coupled with enhancing α-secretase activity, remains the most effective strategy for reducing Aβ generation with minimal mechanism-based side effects in human patients.

Highlights.

Alzheimer’s disease is a disease of synaptic failures.

Aβ peptides have been shown to impair synaptic dysfunctions

The effect of the Aβ-mediated synaptic dysfunctions are multi-facets, and it disrupt functions in glutamatergic, GABAergic, and dopaminergic synapses

BACE1 is indispensable for the generation of Aβ peptides, and inhibition of BACE1 is most promising target for reducing Aβ-mediated synaptic dysfunctions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health to R Yan (NS074256, AG025493, AG046929 and NM103942). R Vassar is supported by NIH R01 AG022560, R01 AG030142, the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund, and the Baila Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- Ables JL, Breunig JJ, Eisch AJ, Rakic P. Not(ch) just development: Notch signalling in the adult brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:269–283. doi: 10.1038/nrn3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramov E, Dolev I, Fogel H, Ciccotosto GD, Ruff E, Slutsky I. Amyloid-beta as a positive endogenous regulator of release probability at hippocampal synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1567–1576. doi: 10.1038/nn.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard P, Alafuzoff I, Carlsson A, Eriksson K, Ericson E, Gottfries CG, Marcusson JO. Loss of dopamine uptake sites labeled with [3H]GBR-12935 in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Neurol. 1990;30:181–185. doi: 10.1159/000117341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allinson TM, Parkin ET, Condon TP, Schwager SL, Sturrock ED, Turner AJ, Hooper NM. The role of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in the ectodomain shedding of angiotensin converting enzyme and the amyloid precursor protein. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:2539–2547. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida CG, Tampellini D, Takahashi RH, Greengard P, Lin MT, Snyder EM, Gouras GK. Beta-amyloid accumulation in APP mutant neurons reduces PSD-95 and GluR1 in synapses. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambree O, Richter H, Sachser N, Lewejohann L, Dere E, de Souza Silva MA, Herring A, Keyvani K, Paulus W, Schabitz WR. Levodopa ameliorates learning and memory deficits in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1192–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anggono V, Huganir RL. Regulation of AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwyl R. Metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term potentiation. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:735–740. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki W, Oda A, Motoki K, Hattori K, Itoh M, Yuasa S, Konishi Y, Shin RW, Tamaoka A, Ogino K. Reduction ofbeta -amyloid accumulation by reticulon 3 in transgenic mice. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012 doi: 10.2174/1567205011310020003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai M, Hattori C, Szabo B, Sasagawa N, Maruyama K, Tanuma S, Ishiura S. Putative function of ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM17 as APP alpha-secretase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:231–235. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02999-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglietto-Vargas D, Moreno-Gonzalez I, Sanchez-Varo R, Jimenez S, Trujillo-Estrada L, Sanchez-Mejias E, Torres M, Romero-Acebal M, Ruano D, Vizuete M, Vitorica J, Gutierrez A. Calretinin interneurons are early targets of extracellular amyloid-beta pathology in PS1/AbetaPP Alzheimer mice hippocampus. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21:119–132. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balducci C, Beeg M, Stravalaci M, Bastone A, Sclip A, Biasini E, Tapella L, Colombo L, Manzoni C, Borsello T, Chiesa R, Gobbi M, Salmona M, Forloni G. Synthetic amyloid-beta oligomers impair long-term memory independently of cellular prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2295–2300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911829107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barao S, Gartner A, Leyva-Diaz E, Demyanenko G, Munck S, Vanhoutvin T, Zhou L, Schachner M, Lopez-Bendito G, Maness PF, De SB. Antagonistic Effects of BACE1 and APH1B–gamma-Secretase Control Axonal Guidance by Regulating Growth Cone Collapse. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1367–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera NP, Betts J, You H, Henderson RM, Martin IL, Dunn SM, Edwardson JM. Atomic force microscopy reveals the stoichiometry and subunit arrangement of the alpha4beta3delta GABA(A) receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:960–967. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.042481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry AE, Klyubin I, Mc Donald JM, Mably AJ, Farrell MA, Scott M, Walsh DM, Rowan MJ. Alzheimer’s disease brain-derived amyloid-beta-mediated inhibition of LTP in vivo is prevented by immunotargeting cellular prion protein. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7259–7263. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6500-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benilova I, Karran E, De SB. The toxic Abeta oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:349–357. doi: 10.1038/nn.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjannet S, Elagoz A, Wickham L, Mamarbachi M, Munzer JS, Basak A, Lazure C, Cromlish JA, Sisodia S, Checler F, Chretien M, Seidah NG. Post-translational processing of beta-secretase (beta-amyloid-converting enzyme) and its ectodomain shedding. The pro- and transmembrane/cytosolic domains affect its cellular activity and amyloid-beta production. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10879–10887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BD, Denis P, Haniu M, Teplow DB, Kahn S, Louis JC, Citron M, Vassar R. A furin-like convertase mediates propeptide cleavage of BACE, the Alzheimer’s beta -secretase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37712–37717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergson C, Mrzljak L, Smiley JF, Pappy M, Levenson R, Goldman-Rakic PS. Regional, cellular, and subcellular variations in the distribution of D1 and D5 dopamine receptors in primate brain. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7821–7836. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-07821.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I, Hiesinger PR. The synaptic maintenance problem: membrane recycling, Ca2+ homeostasis and late onset degeneration. Mol Neurodegener. 2013;8:23. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya R, Barren C, Kovacs DM. Palmitoylation of amyloid precursor protein regulates amyloidogenic processing in lipid rafts. J Neurosci. 2013;33:11169–11183. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4704-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund A, Dunnett SB. Dopamine neuron systems in the brain: an update. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom GS. Amyloid-beta and tau: the trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:505–508. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.5847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgdorff AJ, Choquet D. Regulation of AMPA receptor lateral movements. Nature. 2002;417:649–653. doi: 10.1038/nature00780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buggia-Prevot V, Fernandez CG, Riordan S, Vetrivel KS, Roseman J, Waters J, Bindokas VP, Vassar R, Thinakaran G. Axonal BACE1 dynamics and targeting in hippocampal neurons: a role for Rab11 GTPase. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buggia-Prevot V, Fernandez CG, Udayar V, Vetrivel KS, Elie A, Roseman J, Sasse VA, Lefkow M, Meckler X, Bhattacharyya S, George M, Kar S, Bindokas VP, Parent AT, Rajendran L, Band H, Vassar R, Thinakaran G. A function for EHD family proteins in unidirectional retrograde dendritic transport of BACE1 and Alzheimer’s disease Abeta production. Cell Rep. 2013;5:1552–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buggia-Prevot V, Thinakaran G. Significance of transcytosis in Alzheimer’s disease: BACE1 takes the scenic route to axons. Bioessays. 2015;37:888–898. doi: 10.1002/bies.201500019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Wang Y, McCarthy D, Wen H, Borchelt DR, Price DL, Wong PC. BACE1 is the major beta-secretase for generation of Abeta peptides by neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:233–234. doi: 10.1038/85064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calella AM, Farinelli M, Nuvolone M, Mirante O, Moos R, Falsig J, Mansuy IM, Aguzzi A. Prion protein and Abeta-related synaptic toxicity impairment. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:306–314. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroni P. Inhibitory microcircuit modules in hippocampal learning. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2015;35:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RC, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Effects of PKA and PKC on miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents in CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2797–2800. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.5.2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castello MA, Jeppson JD, Soriano S. Moving beyond anti-amyloid therapy for the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:169. doi: 10.1186/s12883-014-0169-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WP, Huang X, Downs D, Cirrito JR, Koelsch G, Holtzman DM, Ghosh AK, Tang J. Beta-secretase inhibitor GRL-8234 rescues age-related cognitive decline in APP transgenic mice. FASEB J. 2011;25:775–784. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-167213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasseigneaux S, Allinquant B. Functions of Abeta, sAPPalpha and sAPPbeta : similarities and differences. J Neurochem. 2012;120(Suppl 1):99–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Lin R, Chang L, Xu S, Wei X, Zhang J, Wang C, Anwyl R, Wang Q. Enhancement of long-term depression by soluble amyloid beta protein in rat hippocampus is mediated by metabotropic glutamate receptor and involves activation of p38MAPK, STEP and caspase-3. Neuroscience. 2013;253:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K, Cho MH, Seo JH, Peak J, Kong KH, Yoon SY, Kim DH. Calpain-mediated cleavage of DARPP-32 in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell. 2015 doi: 10.1111/acel.12374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu DC, Penney JB, Jr, Young AB. Cortical GABAB and GABAA receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: a quantitative autoradiographic study. Neurology. 1987a;37:1454–1459. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.9.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu DC, Penney JB, Jr, Young AB. Quantitative autoradiography of hippocampal GABAB and GABAA receptor changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 1987b;82:246–252. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge GL, Peineau S, Howland JG, Wang YT. Long-term depression in the CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:459–473. doi: 10.1038/nrn2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa RM, Honjo T, Silva AJ. Learning and memory deficits in Notch mutant mice. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1348–1354. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini C, Ko MH, Jonas MC, Puglielli L. A reversible form of lysine acetylation in the ER and Golgi lumen controls the molecular stabilization of BACE1. Biochem J. 2007;407:383–395. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coultrap SJ, Bayer KU. CaMKII regulation in information processing and storage. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creemers JW, Ines DD, Plets E, Serneels L, Taylor NA, Multhaup G, Craessaerts K, Annaert W, De Strooper B. Processing of beta-secretase by furin and other members of the proprotein convertase family. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4211–4217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006947200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross AJ, Crow TJ, Ferrier IN, Johnson JA, Markakis D. Striatal dopamine receptors in Alzheimer-type dementia. Neurosci Lett. 1984;52:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das U, Scott DA, Ganguly A, Koo EH, Tang Y, Roy S. Activity-induced convergence of APP and BACE-1 in acidic microdomains via an endocytosis-dependent pathway. Neuron. 2013;79:447–460. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RC, Marsden IT, Maloney MT, Minamide LS, Podlisny M, Selkoe DJ, Bamburg JR. Amyloid beta dimers/trimers potently induce cofilin-actin rods that are inhibited by maintaining cofilin-phosphorylation. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice FG, Vieira MN, Bomfim TR, Decker H, Velasco PT, Lambert MP, Viola KL, Zhao WQ, Ferreira ST, Klein WL. Protection of synapses against Alzheimer’s-linked toxins: insulin signaling prevents the pathogenic binding of Abeta oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1971–1976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809158106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Vanderstichele H, Guhde G, Annaert W, Von Figura K, Van Leuven F. Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1998;391:387–390. doi: 10.1038/34910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De SB. Lessons from a failed gamma-secretase Alzheimer trial. Cell. 2014;159:721–726. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De SB, Vassar R, Golde T. The secretases: enzymes with therapeutic potential in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:99–107. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBoer SR, Dolios G, Wang R, Sisodia SS. Differential release of beta-amyloid from dendrite-versus axon-targeted APP. J Neurosci. 2014;34:12313–12327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2255-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M, He W, Tan Y, Han H, Hu X, Xia K, Zhang Z, Yan R. Increased expression of reticulon 3 in neurons leads to reduced axonal transport of beta site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:30236–30245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.480079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkach VA, Oh MC, Guire ES, Soderling TR. Regulatory mechanisms of AMPA receptors in synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrn2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi L, Tang J, Ohno M. Beneficial effects of the beta-secretase inhibitor GRL-8234 in 5XFAD Alzheimer’s transgenic mice lessen during disease progression. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2015;12:13–21. doi: 10.2174/1567205012666141218125042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dislich B, Wohlrab F, Bachhuber T, Mueller S, Kuhn PH, Hogl S, Meyer-Luehmann M, Lichtenthaler SF. Label-free quantitative proteomics of mouse cerebrospinal fluid detects BACE1 protease substrates in vivo. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.041533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong YN, Waxman EA, Lynch DR. Interactions of postsynaptic density-95 and the NMDA receptor 2 subunit control calpain-mediated cleavage of the NMDA receptor. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11035–11045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3722-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eketjall S, Janson J, Jeppsson F, Svanhagen A, Kolmodin K, Gustavsson S, Radesater AC, Eliason K, Briem S, Appelkvist P, Niva C, Berg AL, Karlstrom S, Swahn BM, Falting J. AZ-4217: a high potency BACE inhibitor displaying acute central efficacy in different in vivo models and reduced amyloid deposition in Tg2576 mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33:10075–10084. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1165-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El MD, Granier S, Doumazane E, Scholler P, Rahmeh R, Bron P, Mouillac B, Baneres JL, Rondard P, Pin JP. Distinct roles of metabotropic glutamate receptor dimerization in agonist activation and G-protein coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16342–16347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205838109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzan M, Schnitzler CE, Vasilieva N, Leung D, Choe H. BACE2, a beta -secretase homolog, cleaves at the beta site and within the amyloid-beta region of the amyloid-beta precursor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9712–9717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160115697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferando I, Mody I. Interneuronal GABAA receptors inside and outside of synapses. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014;26:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]