SUMMARY

Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) is a key regulator of smooth muscle and vascular tone and represents an important drug target for treating hypertensive diseases and erectile dysfunction. Despite its importance, its activation mechanism is not fully understood. To understand the activation mechanism, we determined a 2.5 Å crystal structure of the PKG I regulatory (R)-domain bound with cGMP, which represents the activated state. Though we used a monomeric domain for crystallization, the structure reveals that two R-domains form a symmetric dimer where the cGMP bound at high affinity pockets provide critical dimeric contacts. Small angle X-ray scattering and mutagenesis support this dimer model suggesting that the dimer interface modulates kinase activation. Finally, structural comparison with the homologous cAMP-dependent protein kinase reveals that PKG is drastically different from PKA in its active conformation, suggesting a novel activation mechanism for PKG.

Keywords: NO-cGMP signaling, second messengers, cGMP-dependent protein kinase, cyclic nucleotide-binding domain, allosteric activation, crystal structure, small angle xray scattering

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Type I PKG (PKG I) is one of the main receptors of cGMP. It regulates vascular and smooth muscle tone, inhibition of platelet aggregation, and hippocampal and cerebellar learning (Beavo and Brunton, 2002; Francis et al., 2010; Francis and Corbin, 1999; Hofmann et al., 2009). PKG I plays a crucial role in the relaxation of aortic rings and small arteries in the heart - consistent with this, a single amino acid substitution in PKG I causes thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections (TAAD) in humans (Guo et al., 2013).

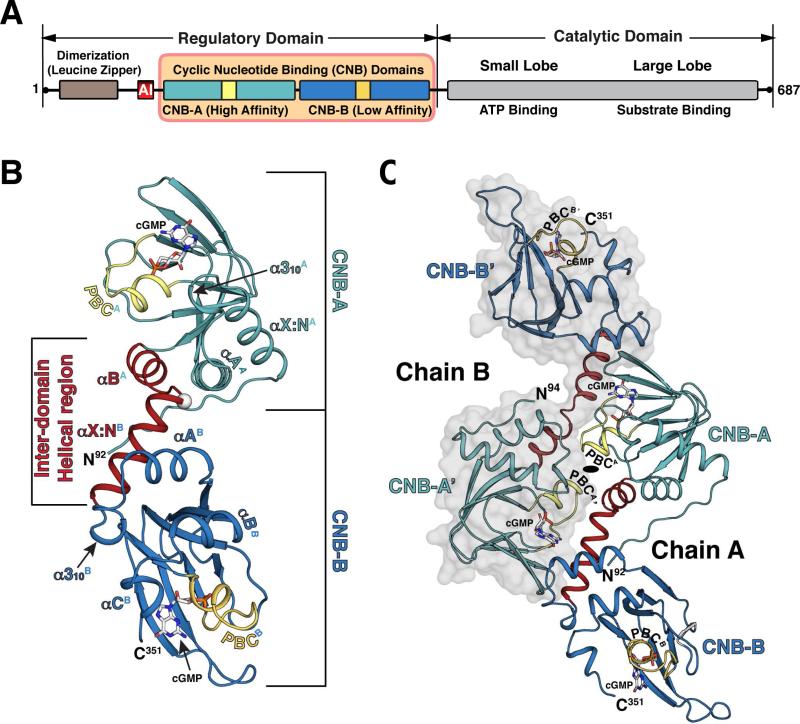

Two isozymes exist for PKG I, α and β (Francis and Corbin, 1999; Hofmann et al., 2009). As splice variants, they differ only in the first ~100 amino acids. They are dimeric proteins with each monomer containing the R- and the C-domains in a single polypeptide chain (Fig. 1A). The R-domain includes an N-terminal leucine zipper (LZ), a flexible linker with an auto-inhibitory (AI) sequence that are isozyme specific, and two CNB domains (CNB-A and B) that are shared between them. Each CNB domain consists of α and β subdomains (Berman et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2014a; Huang et al., 2014b; Kim et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2015a; Kornev et al., 2008; Rehmann et al., 2007) (Fig. 1A). The α subdomain contains the N3A motif and variable numbers of helices at the C-terminus, which flank the β subdomain. The β subdomain contains 8 β strands that fold into a barrel and includes a conserved motif that captures the cyclic phosphate ribose moiety referred to as the Phosphate Binding Cassette (PBC). The two CNB domains are connected by a helical region (Osborne et al., 2011).

Fig. 1. Overall structure of the CNB-A/B:cGMP complex.

(A) Domain organization of PKG I. The CNB-A/B domain used for the crystallization is shaded in orange. AI: Auto-Inhibitory sequence. (B) Structure of the PKG Iβ CNB-A/B:cGMP complex. CNB-A are colored in light teal, CNB-B in blue, PBC in yellow, and the inter-domain helices between the two CNBs in red with their boundaries marked. All cGMPs are shown as stick and colored by atom type (carbon, white; nitrogen, blue; oxygen, red; and phosphorus, orange). The Cα of Gly220 is marked with white sphere. (C) Overall structure of the dimer. Chain B is shown with transparent surface. The two-fold rotation symmetry axis is shown near PBCA. All structure images were generated using PyMOL (Delano Scientific).

Two functional states exist for PKG I: an inactive state where the inhibitory R-domain binds the C-domain presumably with high affinity in the absence of cGMP, and an active state where the R-C holoenzyme dissociates upon cGMP binding, which leads to activation (Alverdi et al., 2008; Wall et al., 2003). SAXS data suggests that the inhibited R-C holoenzyme has a highly asymmetric structure with a maximum linear dimension of 165 Å and the activated R-C becomes extended by 25-30 %. Binding of cGMP to all four cGMP sites in PKG I is required for the structural change and full activation (Wall et al., 2003).

Structural studies of various fragments of the PKG Iβ CNB domains have revealed the molecular details of cGMP specific interactions and the conformational changes that lead to activation (Huang et al., 2014a; Huang et al., 2014b; Kim et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2015a; Osborne et al., 2011). Additionally, a crystal structure of the R-domain containing tandem CNB domains (CNB-A/B) of PKG Iα showed an extended architecture with two domains separated by the helical region referred as the αB/C helices (Osborne et al., 2011). However, because these structures were either of isolated domains or solved with cAMP bound to only one of the cGMP pockets, they do not represent an activated conformation; therefore, the molecular details of the R-domain in the active state remain elusive.

To understand the molecular details for the activated state, we solved the co-crystal structure of the PKG Iβ CNB-A/B (residues 92-351) bound with cGMP at 2.5 Å. The crystal structure shows a symmetrical dimer formed between the two CNB-A/B monomers. Surprisingly, the bound cGMP, PBCA, and the dynamic inter-domain helical region provide a unique interface that allows assembly of the cGMP-mediated dimer. Disruption of this interface increases activation constants with little effect on cGMP affinity. This study reveals a new cGMP-induced dimeric interface that explains the role of the high affinity/non-selective CNB-A and suggests a distinct activation mechanism of PKG I, compared to PKA.

RESULTS

Structure Determination and Overall Structure

The structure of the CNB-A/B:cGMP complex was determined at 2.5 Å by molecular replacement (MR) using the crystal structures of CNB-A and CNB-B (PDB codes: 3OD0 and 4KU7) as search models (Fig. 1B). The asymmetric unit contains two fully ordered CNB-A/B chains that form a dimer with a non-crystallographic symmetry (chains A and B), as well as a partially ordered chain that corresponds to CNB-A (chain C) (Fig. S1A). All chains show clear electron density for the cGMP bound in a syn conformation (Fig. S1C). Overall structures of CNB-A and B domains are essentially the same as those seen in the truncated CNB domains validating our previous structures (Huang et al., 2014b; Kim et al., 2011). In the fully ordered A and B chains, the tandem CNBs are linked by a helical region consisting of the αB helix of the CNB-A, a loop and the αX:N helix of the CNB-B (Fig. 1B). This region, referred as inter-domain helical (IDH) region, bends 100° at Gly220, allowing the extended conformation. Our structure shows that this region provides the dimeric contacts between chains A and B, thus becomes ordered despite its dynamic nature. In contrast, chain C lacks the dimer pair, causing its CNB-B to be disordered (Figs. S1A and S1B). Due to the disordered CNB-B in chain C, we will focus on chains A and B for our structural analysis. Statistics for crystallographic data and structural refinement are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

X-ray Data and refinement statistics.

| cGMP bound | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | 23-ID-D (APS) |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97931 |

| Space group | C 2 2 2 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 73.2, 203.1, 134.6 |

| α,β,γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.00 – 2.50 (2.54-2.50)* |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 7.5 (56.4) |

| I/σI | 14.9 (2.0) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.2 (98.9) |

| Redundancy | 4.1 (4.1) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 36.65 – 2.50 |

| No. reflections | 31051 |

| Rwork/Rfree† | 16.2/22.3 |

| No. atoms | |

| Proteins | 5012 |

| Ligand (cGMP) | 115 |

| Water | 326 |

| B-factors | |

| Overall | 25.64 |

| Protein | 32.00 |

| Ligand (cGMP) | 22.45 |

| Water | 33.56 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.141 |

Highest resolution shell is shown in parenthesis.

5.0% of the observed intensities was excluded from refinement for cross validation purposes.

cGMP binding allows dimer formation between two CNB-A/B domains

The structure reveals that two fully ordered CNB-A/B domains form a dimer mainly through Van Der Waals (VDW) interactions. This buries approximately 900 Å2 of accessible surface area of each monomer (Fig. 1C). Two CNB-A/B domains face against each other in a head-to-tail fashion. Overall structures of the two CNB-A/B domains are essentially the same, superimposing well with a root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) of 1.05 Å for 250 Cα atoms.

The dimeric interface can be divided into three regions (Fig. 2A). The first region includes the tip of the PBC and the αB helix of CNB-A from each chain (PBCA and αBA) that interact through hydrogen bonds and VDW contacts (Figs. 2B and C). Asn189 at the tip of the PBCA from one chain interacts with Gln213’ at the αBA’ helix in the other chain through a hydrogen bond. The other matching pair (Asn189’ and Gln213) shows no hydrogen bond. Due to different side chain orientations of Gln213, they only show VDW interactions.

Fig. 2. Detailed interaction at the CNB-A/B cGMP-mediated dimeric interface.

A. Overall view of the dimeric interface. The residues involved in the dimer interaction are shown as stick. The Cα atoms of Gly220 at the end of αBA are shown as white spheres and the water molecules as blue spheres.

B. Zoomed in views of each region. Key interface residues at each region are shown as stick with gray surface and colored by atom type. The cGMP is shown as stick with red surface. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dotted lines with their distances marked in Å unit.

C. Specific interactions at the dimer interface. The location of each residue within the CNB domains is listed alongside of each amino acid. The water molecule at the interface is marked as W. Hydrogen-bond, and van der Waals interactions are notated as solid and dotted lines, respectively.

The second region is formed between the nonpolar face of PBCA and the α310A helix from one chain and the IDH region from the other, which involves VDW contacts. The side chains of Asp117, Phe118, Tyr188, and Cys190 in one chain form a continuous hydrophobic surface where the side chains of Met217’, Leu221’, and Ile222’ from the other chain dock (Fig. 2B, middle panel). Unlike the first region, the interactions at this region are symmetrical, showing the same matching sets of residues from each chain interacting similarly through VDW contacts.

The third region is most striking because the bound cGMP at the PBCA interacts with the adjacent chain (Fig. 2B, right panel). The cGMP bound at PBCA and strand β5 of one chain interacts with the αX:NB’ helix of the other chain through hydrogen bonds and VDW contacts. In particular, the C2 amino group and the protonated N1 of cGMP at the CNB-A of one chain are within hydrogen bonding distance of OD1 and OD2 of Glu229’ at the αX:NB’ helix of the other molecule. Lys232’ at the αX:NB helix provides additional contacts by interacting with the C6 carbonyl of cGMP via an ordered water molecule and also with the backbone carbonyl of Leu172 at strand β5A.

The overall structure of the PKG Iβ CNB-A/B:cGMP complex is drastically different from that of the PKG Iα CNB-A/B:cAMP complex

The PKG Iβ CNB-A/B:cGMP complex shows a drastically different arrangement of the CNB domains, compared to that of the PKG Iα CNB-A/B:cAMP complex (Fig. 3) (Osborne et al., 2011). While both structures show an extended conformation with no direct contact between CNB-A and B, their relative orientations are very different due to the structural differences at the IDH region. In the CNB-A/B:cAMP complex, the IDH is a continuous helix, which orients the two CNB domains parallel to each other with their cGMP pockets facing the same direction. In our cGMP-bound complex, the region corresponding to the αC helix in the other structure (PKG Iα residues 217-220) becomes a short loop and bends at Gly220 as previously described. Superposition of the two structures at CNB-A shows that the CNB-B domain rotates approximately 180° and moves upward with respect to the CNB-A in the cGMP complex.

Figure 3. Structural comparison with the PKG Iα 78-355:cAMP complex.

Structures of PKG Iβ 92-351:cGMP complex (top), PKG Iα 78-355:cAMP complex (bottom), and their alignment (middle). Zoomed in views on the right showing only the inter-domain helices. The same color themes were used for each structure except for the aligned and zoom in figures. For the aligned figure and zoom in views, the PKG Iβ:cGMP complex is colored in red and the PKG Iα:cAMP in gray with their secondary structures labeled.

cGMP-mediated dimeric contacts facilitate activation

Next we investigated whether the cGMP-mediated contacts plays a role in kinase activation. It is known that in the absence of the LZ domain, PKG Iβ is a monomer in solution (Huang et al., 2014b; Richie-Jannetta et al., 2003; Wall et al., 2003). We reasoned that the cGMP-mediated interchain contacts would only play a role in kinase activation if the two chains are held in close proximity by the LZ domain. Therefore, we mutated key contact residues at the interface either in the full-length (residues: 4-686) PKG Iβ or in a deletion mutant that lacks the LZ domain (Δ55, residues: 56-686) and measured their activation constant for cGMP (KacGMP) (Fig. 4 and Table 2). As previously shown by others (Richie-Jannetta et al., 2003), deleting the LZ domain dramatically increased PKG's KacGMP from 140 nM to 1.5 μM (Fig. 4A). In full-length PKG Iβ, mutating Asn189 at PBCA to alanine increased its KacGMP as much as 18 fold (to 2.5 M) whereas mutating Glu229 to alanine showed a marginal increase of 3.6 fold in KacGMP (Fig. 4B, left panel and Table 2). The same mutations in Δ55 PKG Iβ showed only a slight change in KacGMP when compared to Δ55 wild type (Fig. 4B, right panel). We also investigated if the dimeric interface plays a role in cGMP binding. We constructed isolated R-domains (residues 1-351) containing the Asn189 and Glu229 mutations and measured their cGMP affinities (Table 3). These mutants showed slight increases in EC50 values for cGMP. Mutating Asn189 to alanine increased its EC50 value from 13 nM to 34 nM whereas mutating Glu229 increased to 17.4 nM. Removing the LZ domain had a similar effect by increasing its EC50 value to 23.5 nM. The activation measurements combined with affinity data show that disrupting the cGMP-induced dimeric interface significantly increases its KacGMP while slightly reducing its affinity for cGMP. Taken together, our structural and biochemical data suggest that the dimer interface modulates activation of PKG I.

Fig. 4. Role of the dimeric interface in activation.

A. Activation of PKG Iβ dimer and monomer. Domain schematics for the dimeric PKG Iβ and monomeric Δ55 PKG Iβ without the LZ domain are shown on the left and individual curves with error bars denoting standard error of the mean are shown on the right.

B. Activation of PKG Iβ dimer and monomer with dimeric contact mutations. KacGMP values were measured using a microfluidic mobility shift assay.

Table 2.

Activation constants (Ka) for cGMP

| Human PKG Iβ | Ka for cGMP ± SD (n*) | Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Full-length (4-687) | ||

| WT | 140 ± 25 nM (4) | 1 |

| Asn189Ala | 2.5 ± 0.3 μM (2) | 18 |

| Glu229Ala | 503 ± 49 nM (2) | 3.6 |

| Δ55 (56-687) | ||

| WT | 1.5 ± 0.1 μM (2) | 1 |

| Asn189Ala | 6.4 ± 1.0 μM (2) | 4.3 |

| Glu229Ala | 1.5 ± 0.3 μM (2) | 1 |

Number of independent preparations.

Table 3.

cGMP binding affinities of human PKG Iβ R-dimer wild type and mutants.

| Human PKG Iβ | KD ± SEM (n*) | EC50 ± SEM (n*) |

|---|---|---|

| 8-Fluo-cGMP | cGMP | |

| LZ:CNB-AB (1-351) | ||

| WT | 6.9 ± 0.5 nM (3) | 13.1 ± 1.1 nM (3) |

| Asn189Ala | 8.9 ± 0.5 nM (3) | 33.6 ± 2.6 nM (3) |

| Glu229Ala | 9.5 ± 1.0 nM (3) | 17.4 ± 2.6 nM (3) |

| CNB-AB (92-351) | ||

| WT | 10.3 ± 0.5 nM (3) | 23.5 ± 0.3 nM (3) |

Number of individual measurements.

SAXS data is consistent the structure of the cGMP-mediated regulatory dimer

We previously reported that CNB-A/B (residues 92-369) exists as a monomer with molar excess cGMP using size-exclusion chromatography (Huang et al., 2014b). Moreover, our kinase activation results showed that removing the LZ domain or disrupting the CNB-A/B mediated contacts similarly increases its KacGMP. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that the LZ domain is required for stably forming the cGMP-mediated dimer in solution. To test this, we obtained SAXS data for dimeric R-domain with the LZ domain (residues 1-369) in the presence and absence of cGMP and analyzed their overall conformation (Fig. 5A and Table 4).

Fig. 5. SAXS data of the dimeric R-domains with their models bound to cyclic nucleotides.

A. SAXS patterns from the LZ:CNB-A/B (1-369) with/without cGMP. The curves were offset for better visibility.

B. The SAXS pattern calculated from the EOM models (blue line) is fitted to the experimental SAXS pattern of the LZ:CNB-A/B in the absence of cGMP (red line). The EOM models are shown with representative ensembles of the apo structure at the right.

C. The SAXS pattern calculated from the ensemble of the LZ:CNB-A/B dimer (blue line), based on the CNB-A/B:cGMP complex, is fitted to the experimental SAXS pattern of the LZ:CNB-A/B in the presence of cGMP (red line). The ensemble of the LZ:CNB-A/B used for calculating the SAXS curve is shown at the right.

D. The SAXS pattern calculated from the ensemble of the LZ:CNB-A/B dimer (blue line), based on the CNB-A/B:cAMP complex (3SHR), is fitted to the experimental SAXS pattern of the LZ:CNB-A/B in the presence of cGMP (red line). The ensemble of the LZ:CNB-A/B used for calculating the SAXS curve is shown at the right.

Table 4.

SAXS data collection and scattering derived parameters.

| Without cGMP | With cGMP | |

|---|---|---|

| Data-collection parameter | ||

| Instrument | SIBYLS Beamline | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5 | |

| q range (Å−1) | 0.01 – 0.33 | |

| Exposure time (sec) | 0.5, 1, and 6 | |

| Concentration range (mg ml−1) | 1-9 | |

| Temperature (K) | 283 | |

| Structural parameters | ||

| I (0) (cm−1) [from P (r)] | 741.6 (123.6)* | 928.0 (103.1) |

| Rg (Å) [from P (r)] | 56.4 | 40.4 |

| I (0) (cm−1) (from Guinier) | 742.1 (123.7) | 925.8 (102.9) |

| Rg (Å) (from Guinier) | 53.8 ± 3.0 | 39.7 ± 0.7 |

| Dmax (Å) | 205 ± 10 | 140 ± 8 |

| Porod volume estimate (Å3) | 170,000 ± 10,000 | 175,000 ± 10,000 |

| Monomer dry volume calculated from sequence (Å3) | 56,000 | 56,000 |

| Software employed | ||

| Primary data reduction | PRIMUS | |

| Data processing | PRIMUS / GNOM | |

| Ab initio analysis | DAMMIF | |

| Rigid-body modeling | EOM, BUNCH | |

| Computation of model intensities | CRYSOL | |

| Three-dimensional graphics representation | PYMOL | |

Rg: Radius of Gyration, Dmax; maximum particle size

I (0) / sample concentration (mg/ml)

Since little structural information is available for the full dimeric R-domain, we first constructed two dimeric models by combining the crystal structures of the LZ domain (Casteel et al., 2010) either with the CNB-A/B dimer presented here or with the previously reported PKG Iα CNB-A/B:cAMP dimer (Osborne et al., 2011). Without cGMP, the average dimensions of the dimeric R-domain were much larger (Rg = 53.8 ± 3 Å; Dm = 205 ± 10 Å) than in presence of GMP (Rg = 39.7 ± 0.7 Å; Dm = 140 ± 8 Å), without significant changes in their average volumes (Vdammif = 170,000 Å3 and 175,000 Å ± 10,000 Å3 for apo and cGMP bound R-domain, respectively) (Table 4 and Fig. S2). Additionally, neither of the two dimeric models we generated fit the SAXS pattern, suggesting that the overall solution structure of the R-domain is highly mobile in the absence of cGMP (Fig. S3). Indeed, the apo SAXS pattern was fit well by an ensemble of models (chosen from a pool of 10,000 random structures) we generated using ensemble optimization method (EOM) where the LZ domain was kept fixed, and the monomeric CNB-A/B domains were allowed to move freely through the flexible linker between the LZ and the CNB-A/B (χ = 1.0) (Figs. 5B, S4, and S5). Compared to the pool of structures, the Dm and Rg distribution of the selected models indicated a bimodal character, with Dm peaks at 150-180 Å and 230-260 Å. The smaller Dm values were achieved by models where the CNB-A/B domains clustered close to the LZ domain. The extended models had the A/B domains distant from the LZ (Fig. S5). Thus, the EOM models combined with the SAXS pattern suggest that in the absence of cGMP the CNBA/B domains explore a large range of motions allowed by the flexible linker between the LZ and CNB domains (Figs. 5B and S5).

In major contrast, the dimeric R-domain showed different SAXS patterns in the presence of cGMP (Fig. 5A). The SAXS pattern showed that the overall size of the R-domain becomes smaller upon binding of cGMP (Rg = 39.7 ± 0.7 Å; Dm = 140 ± 8 Å). To account for flexibility between the LZ region and the CNB-A/B dimer, we manually generated a pool of 60 models for each of the two possible R-dimers by randomly translating the CNB-A/B dimers (either taken from our cGMP dimer, or based on the cAMP dimer) around the fixed LZ domains using Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004) and calculated theoretical SAXS curves for comparison using FoXS (Schneidman-Duhovny et al., 2010). The best fit for a single model chosen from our cGMP bound R-dimer pool was in already in reasonable agreement with the SAXS data (χ=6.29). The fit was significantly improved by choosing a 3-model ensemble (χ=4.96 for a 3-model ensemble) in support of flexible linkage between LZ and AB domains in presence of cGMP (Figs. 5C and S6). However, the best single model based on the cAMP bound CNB-A/B dimers fitted the data poorly (χ=19.75), and this fit was not significantly improved by ensemble models (χ=19.69 for models composed of 2 or more single molecules) (Figs. 5D and S6), thus failing to support that this cAMP-based R-model was present in solution. Taken together, our SAXS analysis strongly suggests that the cGMP-mediated dimer seen in our crystal structure exists in the solution and that the dimeric R-domain undergoes major conformational changes upon cGMP binding.

DISCUSSION

Our structural analysis combined with biochemical data allowed us to draw three conclusions. First, cGMP binding facilitates the dimerization of two CNB-A/B domains, which is distinct from the dimer interface formed at the LZ domain. The crystal structure of the PKG Iβ 92-351:cGMP complex showed that the cGMP pocket of CNB-A along with the bound cGMP provides the majority of the dimeric interface (Fig. 2). Because the CNB-A/B domains did not dimerize in the presence of cGMP under the size-exclusion chromatography conditions we used (Huang et al., 2014b), we hypothesized that the high protein concentration in the crystal allowed us to capture a transient dimer which otherwise only forms in PKG I when the LZ domain is present.

This dimer model is consistent with our SAXS analysis on the dimeric R-domain (Fig. 5). As for the dimeric R-domain, the SAXS data in the presence of cGMP suggest a compact shape with the volume and profile that matched the R-domain dimer model we generated using our CNB-A/B:cGMP structure. In contrast, the R-dimer model using the structure of CNB-A/B:cAMP complex (Osborne et al., 2011) did not fit to the SAXS data, suggesting that the R-domain with cAMP occupying only the CNB-A pocket exhibits a different conformation. In the absence of cGMP, the SAXS data combined with EOM suggested that the A/B domains of the R-dimer are monomeric and flexibly attached to the LZ dimer. Given the bimodal distribution of Dm and Rg in absence of cGMP, it is plausible that the lower Dm species are structures similar to the cGMP-bound forms. Thus, in absence of cGMP, the AB domain might sample the dimeric conformation it adopts in presence of cGMP. However our SAXS data provide insufficient constraints to assess this possibility with confidence. The data suggest that the LZ domain functions as a tether, which keeps the CNB-A/B domains in close proximity and facilitates the formation of the cGMP-mediated dimeric interface. In summery, the SAXS data combined with modeling of the R-dimer suggest that our dimeric cGMP-bound A/B domain structure represents the activated conformation of the PKG I R-domain.

Second, our mutation analysis suggests important roles of the cGMP-induced dimeric interface in kinase activation and cGMP affinity (Fig. 4 and Table 2). Based on our structure, we hypothesized that disrupting the dimeric interface would destabilize the active conformation and thus increase KacGMP. Consistent with this hypothesis, removing the LZ domain (Δ55 PKG Iβ) or mutating key dimer contacts increases KacGMP values. In particular, mutating Asn189 at the center of the interface (Fig. 2B, right panel) has a similar effect on KacGMP as removing the LZ domain. Mutating Glu229 shows less of an effect on KacGMP, suggesting that Glu229-cGMP interaction contributes less to the dimeric interface. This difference in KacGMP values can be explained by the different nature of the dimeric interactions for these two regions. The structure shows that the dimeric interactions at Asn189 are direct, involving both hydrogen bonds and VDW contacts whereas the interactions at Glu229 are indirect, mediated through the bound cGMP (Figs. 2B and 2C). Moreover, because the dimer interactions near Glu229 are mainly through VDW interactions (middle panel of Fig. 2B), mutating Glu229 to alanine is likely to have a minor effect on destabilizing the dimer. The same mutations in the monomeric Δ55 PKG Iβ (Asn189Ala and Glu229Ala) showed modest or no change in their KacGMP values compared to the monomeric wild type, suggesting that the LZ domain is required and facilitates the dimeric interaction between the two CNB-A/B domains.

The effects seen in cGMP binding are consistent with the structure and suggest the role of the dimeric interface in cGMP affinity. The structure shows that, while Asn189 does not directly interact with cGMP, it stabilizes the CNB-A/B dimeric interface, which shields the A-site from solvent. Thus mutating Asn189 to alanine would destabilize the dimeric interface exposing the A-site to solvent. This would increase the dissociation rate of the A-site (Richie-Jannetta et al., 2003), which is consistent with the weaker cGMP affinity of Asn189Ala, compared to the wild type. While directly interacting with cGMP, Glu229 contributes less to stabilizing the CNB-A/B dimer interface, which explains a slight reduction in cGMP affinity seen in Glu229Ala.

Dimer formation at the CNBs is consistent with our previous Hydrogen/Deuterium (H/D) exchange mass spectrometry (HDXMS) results (Lee et al., 2011). We analyzed H/D exchange in isolated PKG Iβ R-domain constructs with and without the LZ domain, and found that the IDH region (referred previously as the αB/C helix) between the CNBs was stabilized upon cGMP binding only when the LZ domain was present. It was unclear why the LZ domain would be necessary for cGMP-induced stabilization of the IDH region. The interchain contacts seen in our crystal structure provide a mechanistic explanation for this effect.

Lastly, the conformation of PKG I in the active state is distinct from that of PKA, suggesting a different activation mechanism for PKG I. Comparison with the structures of PKA R-subunits shows that PKG Iβ is drastically different in its overall structure of monomer and the dimer assembly (Boettcher et al., 2011; Bruystens et al., 2014; Ilouz et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2012) (Fig. 6). The structures of the monomeric PKA R-subunits fully bound with cAMP show a highly compact conformation with the CNB-A and B domains directly interacting with one another (intrachain contacts) (Fig. 6A, right) (Bruystens et al., 2014; Su et al., 1995). The dynamic αB/C helix (corresponding to IDH in PKG I) that connects two CNB domains bends in the middle, forming several intrachain contacts (Figs. 6A and S7). The hallmark of PKA's intrachain contacts is the capping interaction where a conserved hydrophobic residue (Trp260 in PKA RIα) from the CNB-B (αAB-helix) shields the adenine moiety of the bound cAMP at the CNB-A through a π-stacking interaction and acts as a lid (intrachain capping) (Figs. 6A and S7) (Su et al., 1995). The recent crystal structure of PKA RIα dimer reveals that RIα forms additional dimer contacts within the tandem CNB-domains, but these contacts are limited to the N3A motifs of the CNB-A, and the bound cAMP does not provide the dimer interaction (Fig. 6B) (Bruystens et al., 2014). Unlike the compact monomer of PKA RIα, the R-domain of PKG I shows a highly extended conformation with no intrachain contact. The IDH region is also dynamic, but this region helps orient the CNB-A/B domain for the interchain contacts. The hallmark of the interchain contacts is that Glu229 at the CNB-B of one chain specifically forms hydrogen bonds with the cGMP bound at the CNB-A of the other chain, providing PKG specific interchain contact.

Fig. 6. Structure comparison with PKA RIα monomer and dimer.

A. Monomers of PKG Iβ and PKA RIα (PDB code 1RGS) in an active conformation at the top and their alignment at the bottom. The αX:NB’ helix belonging to the other chain is shown to orient the dimeric interface. In the alignment figure, PKG is colored in red and PKA in gray.

B. Dimers of PKG Iβ and PKA RIα. The B-chains are shown with transparent surface.

Unlike in PKA, PKG has the R- and C-domains on the same chain. This may explain why the cGMP-induced dimeric interface facilitates activation of PKG. The regulation mechanisms of both PKG and PKA are largely dependent on the high affinity interaction between the R- and C-domains in the absence (estimated to be < 0.1 nM) of cyclic nucleotide and the drastic reduction of their affinity in the presence (> 1μM) (Døskeland et al., 1993; Francis and Corbin, 1999). In PKA, because the R- and C-subunits are separate polypeptide chains, they diffuse away upon activation, preventing possible reassociation that causes proximity-mediated inhibition. Unlike PKA, the presence of the R- and C-domains on the same peptide chain in PKG can enhance the R-C interaction and this may cause the proximity-mediated inhibition during elevation of cGMP. Thus, we propose that cGMP binding enables the formation of the CNB-A/B dimeric interface locking the R-domain into its active conformation. This, in turn, may prevent the reassociation of the R- and C-domains and can help sustaining kinase activity (Fig. 7). Additionally, dimer formation shields the bound cGMP from solvent, subsequently reducing its release and degradation by phosphodiesterases. This would also increase the half-life of cGMP and sustain PKG activity. Finally, the role of the cGMP-induced interface has important implications for the rational design of PKG agonists in the treatment of hypertensive disease. We speculate that this novel dimeric interface explains why the known cGMP-analogue activation profiles are different between the two cGMP-binding pockets and also very distinct from that of PKA's (Corbin et al., 1986; Schlossmann and Desch, 2009). Therefore, the interactions within the CNB-A/B mediated interface need to be considered in designing a potent PKG agonist.

Fig. 7. Model of PKG I Activation.

cGMP binding at CNB domains induces a large conformational change in the R-domain, releasing the C-domain, and the R-domain forms a novel dimer interface through the CNB domains. AI: Auto-Inhibitory sequence. Dotted rectangles indicate the inter-domain helical region.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construct design, protein expression and purification

Human PKG Iβ construct (92-351) for crystallization were ligated into pQTEV (Bussow et al., 2005). All PKG Iβ proteins used for the crystallization, SAXS, and the cGMP-binding assay were expressed in TP2000 E. coli (Kim et al., 2015b; Roy and Danchin, 1981). The his-tagged PKG Iβ proteins were purified with Bio-Rad IMAC resin on ÄKTA purifier system (GE Healthcare), and then the his-tag was removed by TEV protease. The tagless PKG Iβ proteins were further purified using Mono Q 10/100 GL (GE Healthcare) and Hiload 16/60 Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare).

Crystallization, Data Collection, Phasing, Model Building, and Refinement

To obtain crystals, the protein sample was pre-incubated with 10 mM cGMP and concentrated to 25 mg. Plate crystals belonging to a C222 space group were obtained in 0.2 M ammonium sulfate, 17.5% PEG 8000 (w/v), 10% Isopropanol, and 0.1 M HEPES at pH 8.0 at 22 °C. Diffraction experiments were performed at beamline 8.2.1 at the ALS (Berkeley, CA, USA) and at GM/CA CAT (23-ID-D) at the APS (Argonne, IL, USA). Diffraction data were processed using HKL3000 (Minor W et al., 2006) (Table 1). The structure was determined by Phaser-MR (McCoy, 2007) using the truncated models of the CNB-A and B domains of PKG Iβ (PDB code: 3OD0 and PDB code: 4KU7) as MR probes. The model was manually built using Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and refined using Refmac5 (Murshudov et al., 2011) and Phenix. Refine (Afonine et al., 2012) with restrained-structure-refinement implementing TLS refinement (Painter and Merritt, 2006). The final model is refined to Rwork and Rfree values of 17.05 % and 21.90 % (Table 1).

Small Angle X-ray Scattering

Human PKG Iβ (residues 1-369) was purified as described above. The samples for SAXS were prepared in the range of 5-20 mg/ml with and without 10 mM cGMP in 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM TCEP. Buffer contribution was subtracted from each protein scattering curve. The data were collected at beamline 12.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source (Berkeley, CA, USA) and recorded for a total q range from 0.01 to 0.33 Å−1. Data analysis were performed by using PRIMUS, GNOM, DAMMIN, GASBOR, CRYSOL, DAMAVER, and SASREF (Petoukhov et al., 2007). SAXS data collection and scattering derived parameters are shown in Table 4.

Fluorescence polarization

The direct fluorescence polarization (FP) assay was performed following the procedure from Huang et al (Huang et al., 2014b). Measurements were performed in 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM MOPS plus 0.005% (w/v) CHAPS pH 7.0 using the Synergy™ H1 microtiter plate reader at room temperature in a 384 well microtiterplate (BioTek, Optiplate, black). The protein concentration was varied while the concentration of 8-Fluo-cGMP (Biolog Life Science Institute, Bremen, Germany) was fixed at 1 - 5 nM. The FP signal was detected for 2 seconds at Ex 485 nm and Em 535 nm with a PMT Voltage of 1.100 V. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 5.03 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) by plotting the polarization signal in mPol against the logarithm of the protein concentration. The KD values were calculated from sigmoidal dose-response curves.

For FP competition experiments the protein concentration and the concentration of 8-Fluo-cGMP were fixed to give a polarization signal that was 50% of the maximum value obtained from direct FP measurements. The protein/8-Fluo-cGMP mixture was incubated with varying concentrations of unlabeled cGMP or cAMP (Biolog Life Science Institute, Bremen, Germany). FP signals were detected as indicated above. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 5.03 by plotting the polarization signal in mPol against the logarithm of the cyclic nucleotide concentration. The EC50 values were calculated from sigmoidal dose-response curves.

Microfluidic mobility-shift assay

Kinase activity was determined using a microfluidic mobility-shift assay on a Caliper DeskTop Profiler (Caliper Life Sciences, PerkinElmer) following the procedure described in Huang et al (Huang et al., 2014b). Protein was incubated for 2 hr at ambient temperature in a 384 well assay plate (Corning®, low volume, non-binding surface) in 20 μl buffer (20 mM MOPS pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 1 mM DTT, 0.05% L-31, 10 μM FITC-Kemptide, 990 μM Kemptide, 1 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2) and various concentrations of cGMP, respectively. Reaction mixtures without cyclic nucleotide were used as controls. For electrophoretic separation of substrate and product a ProfilerPro™ LabChip (4-sipper mode; Caliper Life Sciences, PerkinElmer) was used under the following conditions: downstream voltage −150 V, upstream voltage −1,800 V with a screening pressure of −1.7 psi. Substrate conversion was plotted against the logarithmic cyclic nucleotide concentration and activation constants (Ka) were calculated from sigmoidal dose-response curves employing GraphPad Prism 5.03.

Coordinates

Atomic coordinate and structure factor of the CNB-A/B:cGMP complex of human PKG Iβ have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org) under accession numbers 4Z07.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Structure of monomeric PKG I R reveals a new dimeric interface mediated by cGMP.

Mutagenesis of the key interface residues reduces cGMP binding and activation.

SAXS analysis of the PKG I R-dimer supports the cGMP-mediated dimer model.

The dimeric interface may acts as a “safety lock” to ensure kinase activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gilbert Y. Huang (M.D. Anderson Cancer Center) and Kim lab members for critical reading of the manuscript and E. Franz (U of Kassel) for technical support. We specially thank R. Sanishvili, M. Becker, and C. Ogata (GM/CA@APS) for their kind assistance with data collection during the APS-CCP4 summer school in 2012. C.K. was funded by the NIH grant R01 GM090161 and R21 HL111953. The CCP4 school was funded partly by the NCI (Y1-CO-1020), the NIGMS (Y1-GM-1104), a grant from CCP4, and the STFC in the UK. Research by S.T.A. reported in this publication was supported by funding from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). F.W.H. was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research Project NO PAIN (FKZ 0316177F) and the European Union (EU) FP7 collaborative project AFFINOMICS (Contract No. 241481). The Berkeley Center for Structural Biology is supported in part by the NIH, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The SIBYLS beamline (ALS) is supported in part by US DOE program Integrated Diffraction Analysis Technologies (IDAT) and the NIH project MINOS (R01 GM105404).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

J.J.K., and C.K. designed the experiments required for addressing the questions in this study. J.J.K. designed the constructs and purification protocols for crystallization. J.J.K. identified and optimized crystallization conditions. J.J.K., and B.S. collected diffraction images. J.J.K., and A.S.R. solved the structures and refined the crystallographic models. J.J.K., and A.S.R. designed, built and purified the full-length R-domain of PKG Iβ wild type and mutant constructs for the KD/EC50 measurements and the small angle X-ray scattering experiment. J.J.K. generated the KD/EC50 measurements. S.T.A., J.J.K., and A.S.R. analyzed the small angle X-ray scattering data. J.J.K., R.L., and D.E.C., built and purified the full-length PKG Iβ wild type and mutant constructs for the Ka measurements and R.L., J.J.K., and F.W.H. measured activation constants. J.J.K., and C.K. wrote the bulk of the manuscript and created the figures. All authors commented on the manuscript.

References

- Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH, Adams PD. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alverdi V, Mazon H, Versluis C, Hemrika W, Esposito G, van den Heuvel R, Scholten A, Heck AJ. cGMP-binding prepares PKG for substrate binding by disclosing the C-terminal domain. J Mol Biol. 2008;375:1380–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beavo JA, Brunton LL. Cyclic nucleotide research --still expanding after half a century. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:710–718. doi: 10.1038/nrm911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM, Ten Eyck LF, Goodsell DS, Haste NM, Kornev A, Taylor SS. The cAMP binding domain: an ancient signaling module. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:45–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408579102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher AJ, Wu J, Kim C, Yang J, Bruystens J, Cheung N, Pennypacker JK, Blumenthal DA, Kornev AP, Taylor SS. Realizing the allosteric potential of the tetrameric protein kinase A RIalpha holoenzyme. Structure. 2011;19:265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruystens JG, Wu J, Fortezzo A, Kornev AP, Blumenthal DK, Taylor SS. PKA RIalpha homodimer structure reveals an intermolecular interface with implications for cooperative cAMP binding and Carney complex disease. Structure. 2014;22:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussow K, Scheich C, Sievert V, Harttig U, Schultz J, Simon B, Bork P, Lehrach H, Heinemann U. Structural genomics of human proteins -target selection and generation of a public catalogue of expression clones. Microb Cell Fact. 2005;4 doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casteel DE, Smith-Nguyen EV, Sankaran B, Roh SH, Pilz RB, Kim C. A crystal structure of the cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase I{beta} dimerization/docking domain reveals molecular details of isoform-specific anchoring. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:32684–32688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.161430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JD, Ogreid D, Miller JP, Suva RH, Jastorff B, Døskeland SO. Studies of cGMP analog specificity and function of the two intrasubunit binding sites of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1986;261:1208–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Døskeland SO, Maronde E, Gjertsen BT. The genetic subtypes of cAMP-dependent protein kinase--functionally different or redundant? Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1993;1178:249–258. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis SH, Busch JL, Corbin JD, Sibley D. cGMP-dependent protein kinases and cGMP phosphodiesterases in nitric oxide and cGMP action. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:525–563. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis SH, Corbin JD. Cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases: intracellular receptors for cAMP and cGMP action. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1999;36:275–328. doi: 10.1080/10408369991239213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo DC, Regalado E, Casteel DE, Santos-Cortez RL, Gong L, Kim JJ, Dyack S, Horne SG, Chang G, Jondeau G, et al. Recurrent Gain-of-Function Mutation in PRKG1 Causes Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Acute Aortic Dissections. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93(2):398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F, Bernhard D, Lukowski R, Weinmeister P. cGMP regulated protein kinases (cGK). Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2009:137–162. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GY, Gerlits OO, Blakeley MP, Sankaran B, Kovalevsky AY, Kim C. Neutron diffraction reveals hydrogen bonds critical for cGMP-selective activation: insights for cGMP-dependent protein kinase agonist design. Biochemistry. 2014a;53:6725–6727. doi: 10.1021/bi501012v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GY, Kim JJ, Reger AS, Lorenz R, Moon EW, Zhao C, Casteel DE, Bertinetti D, Vanschouwen B, Selvaratnam R, et al. Structural basis for cyclic-nucleotide selectivity and cGMP-selective activation of PKG I. Structure. 2014b;22:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilouz R, Bubis J, Wu J, Yim YY, Deal MS, Kornev AP, Ma Y, Blumenthal DK, Taylor SS. Localization and quaternary structure of the PKA RIbeta holoenzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12443–12448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209538109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Cheng CY, Saldanha SA, Taylor SS. PKA-I holoenzyme structure reveals a mechanism for cAMP-dependent activation. Cell. 2007;130:1032–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Casteel DE, Huang G, Kwon TH, Ren RK, Zwart P, Headd JJ, Brown NG, Chow DC, Palzkill T, et al. Co-crystal structures of PKG Ibeta (92-227) with cGMP and cAMP reveal the molecular details of cyclic-nucleotide binding. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Flueck C, Franz E, Sanabria-Figueroa E, Thompson E, Lorenz R, Bertinetti D, Baker DA, Herberg FW, Kim C. Crystal Structures of the Carboxyl cGMP Binding Domain of the Plasmodium falciparum cGMP-dependent Protein Kinase Reveal a Novel Capping Triad Crucial for Merozoite Egress. PLoS pathogens. 2015a;11:e1004639. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Huang GY, Rieger R, Koller A, Chow D, Kim C. A Protocol for Expression and Purification of Cyclic Nucleotide–Free Protein in Escherichia coli. In: Cheng X, editor. Cyclic Nucleotide Signaling. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Florida, USA: 2015b. pp. 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kornev AP, Taylor SS, Ten Eyck LF. A generalized allosteric mechanism for cis-regulated cyclic nucleotide binding domains. PLoS computational biology. 2008;4:e1000056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Li S, Liu T, Hsu S, Kim C, Woods VL, Jr., Casteel DE. The amino terminus of cGMP-dependent protein kinase Ibeta increases the dynamics of the protein's cGMP-binding pockets. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2011;302:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ. Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2007;63:32–41. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906045975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor W, Cymborowski M, Otwinowski Z, M C. HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution-from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:859–866. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906019949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Skubak P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2011;67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne B, Wu J, McFarland C, NIckl C, Sankaran B, Casteel DE, Woods VJ, Kornev A, Taylor S, Dostmann WR. Crystal structure of cGMP-dependent protein kinase reveals novel site of interchain communication. Structure. 2011;19:1317–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petoukhov MV, Konarev PV, Kikhney AG, Svergun DI. ATSAS 2.1 -towards automated and web-supported small-angle scattering data analysis. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2007;40:s223–s228. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Capturing cyclic nucleotides in action: snapshots from crystallographic studies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:63–73. doi: 10.1038/nrm2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie-Jannetta R, Francis SH, Corbin JD. Dimerization of cGMP-dependent protein kinase Ibeta is mediated by an extensive amino-terminal leucine zipper motif, and dimerization modulates enzyme function. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:50070–50079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Danchin A. Restriction map of the cya region of the Escherichia coli K12 chromosome. Biochimie. 1981;63:719–722. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(81)80220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlossmann J, Desch M. cGK substrates. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2009:163–193. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneidman-Duhovny D, Hammel M, Sali A. FoXS: a web server for rapid computation and fitting of SAXS profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W540–544. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, Dostmann WR, Herberg FW, Durick K, Xuong NH, Ten Eyck L, Taylor SS, Varughese KI. Regulatory subunit of protein kinase A: structure of deletion mutant with cAMP binding domains. Science. 1995;269:807–813. doi: 10.1126/science.7638597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall ME, Francis SH, Corbin JD, Grimes K, Richie-Jannetta R, Kotera J, Macdonald BA, Gibson RR, Trewhella J. Mechanisms associated with cGMP binding and activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:2380–2385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0534892100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Smith-Nguyen EV, Keshwani MM, Deal MS, Kornev AP, Taylor SS. Structure and allostery of the PKA RIIbeta tetrameric holoenzyme. Science. 2012;335:712–716. doi: 10.1126/science.1213979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.