Abstract

Introduction

Augmented reality (AR) fuses computer-generated images of preoperative imaging data with real-time views of the surgical field. Scopis Hybrid Navigation (Scopis, GmbH, Berlin, Germany) is a surgical navigation system with AR capabilities for endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS).

Methods

Pre-dissection planning was performed with Scopis Hybrid Navigation software followed by ESS dissection on 2 human specimens using conventional ESS instruments.

Results

Pre-dissection planning included creating models of relevant frontal recess structures and the frontal sinus outflow pathway on orthogonal CT images. Positions of the optic nerve and internal carotid artery were marked on the CT images. Models and annotations were displayed as an overlay on the endoscopic images during the dissection, which was performed with electromagnetic surgical navigation. The accuracy of the AR images relative to underlying anatomy was better than 1.5 mm. The software's trajectory targeting tool was used to guide instrument placement along the frontal sinus outflow pathway. AR imaging of the optic nerve and internal carotid artery served to mark the positions of these structures during the dissection.

Conclusions

Surgical navigation with AR was easily deployed in this cadaveric model of ESS. This technology builds upon the positive impact of surgical navigation during ESS, particularly during frontal recess surgery. Instrument tracking with this technology facilitates identifying and cannulation of the frontal sinus outflow pathway without dissection of the frontal recess anatomy. AR can also highlight “anti-targets” (i.e., structures to be avoided), such as the optic nerve and internal carotid artery, and thus reduce surgical complications and morbidity.

Keywords: Augmented reality, image-guided surgery, endoscopic sinus surgery, cadaveric model

Introduction

Nasal endoscopy, coupled with contemporary medical cameras, provides magnified, bright, high-resolution images of the nasal and sinus cavities; however, the resultant images are only two-dimensional (2D) representations of a complex three-dimensional (3D) space. Thus, over a 25 year period, surgeons have endorsed images-guided surgery (IGS) technology as means to avert perceptual distortions.1 In fact, IGS has been associated with better outcomes and reduced complications.2 Conventional IGS systems separate localization information (i.e., CT scan images) from surgical field anatomy, and as a result, the surgeon must make mental extrapolations that introduce potential errors, obviating some of the advantages provided by the IGS technology.

Augmented reality (AR), which fuses preoperative imaging data and intra-operative images, may enhance the available visual information during surgery. Through AR, the surgeon may annotate images preoperatively and then visualize that information as a projection that is displayed over the anatomy in the surgeon's view.3,4 To create this AR view for endoscopic procedures, the annotated models and endoscopic images must be aligned and then the computer system must present a hybrid image of actual endoscopy and the corresponding annotated models. Technically, endoscopic procedures require a registration of the view obtained through the conventional telescope with corresponding 3D models built from preoperative imaging data.5 The feasibility of overlaying target models on endoscopic images has been confirmed in a cadaveric model of sinus surgery and in a brief clinical report;4 however, this report did not describe the specific clinical utility provided by augmented reality information. The current project uses a navigation system that is commercially available outside the US as a platform for exploring applications of AR in endoscopic sinus surgery.

Methods

Scopis Hybrid Navigation (Scopis, GmbH, Berlin, Germany) is an IGS system that supports electromagnetic and optical tracking as well as simultaneous hybrid tracking. The surgeon may select the tracking technology for a specific procedure based upon procedural needs and surgeon preferences. In addition, this platform offers AR views that overlay annotations and models, created with Scopis Building Blocks planning software, onto real-time, live endoscopic images. Currently, the system is not commercially available in the US, but the system is available in Europe as well as selected countries in Asia.

A total of 2 fresh human cadaveric specimens (4 sides) were used for this project. A high resolution sinus CT (0.6 mm contiguous slices, bone algorithm) was obtained before dissection. Each dissection was proceeded with a pre-dissection planning phase, performed with Scopis Building Blocks software that was used to review the CT images. In addition, this software was used to create models of relevant frontal recess cells and frontal sinus outflow tract as well as mark critical structures (such as the optic nerve); these annotations were then used during the endoscopic dissection. After completion of the pre-dissection planning, the surgical dissection was performed. A contour-based registration was performed for standard navigation, and an image-to-image registration of the endoscopic view and the annotated models, was also completed, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Electromagnetic tracking, rather than optical tracking, was used for both dissections. For each dissection, target registration accuracy was estimated by comparing measured positions of instrument tips against known anatomic landmarks in the surgical field. Aspirators with distal tip tracking and a wire with a distal tip sensor were used during the dissections. For each dissection, the Scopis AR view was used to guide instrument position and tissue removal. The video output of the Scopis computer was recorded for later review.

Results

Endoscopic dissection with augmented reality was achieved in both dissections. Target registration accuracy for surgical navigation was estimated at 1.5 mm or better. The AR models, created during preoperative planning, were felt to be accurate in that they represented the underlying anatomy observed in the operating field. It should be noted that the images were still 2D projections of 3D anatomy. As a result of this limitation (intrinsic to 2D monitors), the surgeons used tactile cues (i.e., touch of relevant structures) to align the annotated models to the underlying anatomy. Alternatively, the Scopis software displayed the distance from the tracked instrument tip to the target on the surgical model, and surgeon also used this information to further align the AR models to the underlying anatomy.

Before frontal recess dissection, models of frontal sinus anatomy were created in the Building Blocks software. These models were then projected on the endoscopic view during the frontal recess dissection (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The outflow path was similarly marked in the Building Blocks software and then a series of surgical targets were placed upon this model. The Scopis augmented reality view guided placement of both a frontal aspirator (Figure 3) and balloon device (Figure 2) during cannulation of the frontal sinus. A similar approach was used at the sphenoid sinus (Figure 4). As the tip of the device approached and passed through the interval target on the pathway, the software provided visual cues that guided the surgeon during the cannulation process. Finally, the Scopis Building Blocks was used to create a model of the optic nerve, which was then projected upon the endoscopic view (Figure 5), providing information about this critical structure before it was directly visualized.

Figure 1.

Frontal recess cells (AN, agger nasi cell; FC1, type 1 frontal sinus; SBC, suprabullar cell) are projected upon this partially dissected left frontal recess, as viewed with a 45 degree telescope. The position of the instrument tip is displayed on the orthogonal CT images on the left.

Figure 2.

Frontal recess cells (agger nasi cell, in orange; type 1 frontal cell in green) is projected upon a partially dissected left frontal recess, as viewed with 30 degree scope. The tip of a Ventera-R balloon catheter (Smith & Nephew/ENTrigue Surgical, Austin, TX) is displayed on the orthogonal CT images on the left.

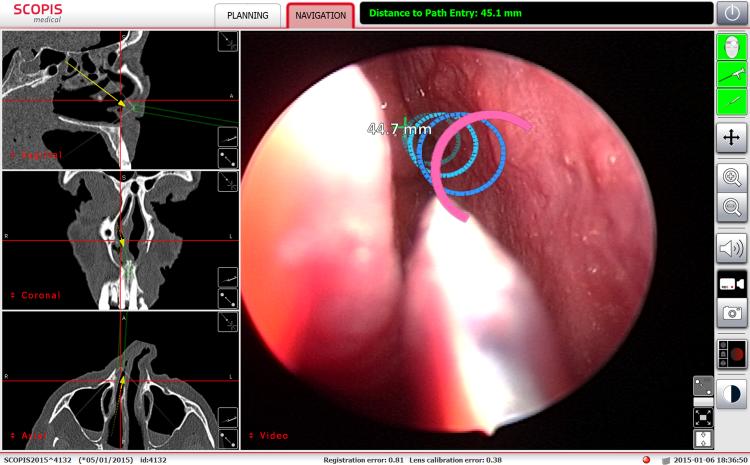

Figure 3.

The frontal sinus ouflow tract is projected upon the endoscopic image of the left agger nasi region. The rings change appearance as the surgeon approaches and then passes through each ring.

Figure 4.

These rings highlight the path to the right sphenoid sinus.

Figure 5.

The optic nerve is projected as yellow structure oriented obliquely in the center of this image of the right ethmoid cavity, which has been partially dissected. This projection allows the surgeon to know the position of this critical structure before it comes into direct view.

Discussion

AR in the operating room has been described as encompassing 3 distinct phases of “(1) generation of virtual patient-specific model; (2) visualization of the model in the operative field; (3) registration, which corresponds to an accurate overlaying of the 3D model onto the real patient’ operative images.”6 This current report summarizes the application of Scopis Augmented Reality in cadaveric model for sinus surgery and confirmed successful execution of all 3 phases.

Scopis Hybrid Navigation has unique features essential for the application of AR in this model of endoscopic sinus surgery. An earlier version of this platform featured optical-based tracking and was described by Winne et al. in a report that included both a cadaveric study and a case series.4 The current platform, used in this report, incorporates an optional electromagnetic-based tracking technology, and thus permits the incorporation of microsensors, which may be incorporated into the distal tips of instruments and wires. In addition, the current softeware offers a novel preoperative planning phase, known as Building Blocks; this software package facilitates highlighting of relevant anatomy throughout the paranasal sinuses and adjacent structures. In particular, the Scopis software applies the concept of ‘building blocks’ for frontal recess anatomy (as proposed by Wormald).7 Furthermore, this navigation system incorporates technology for the calibration of standard endoscopic image with CT-scan derived models, a variation of an approach originally proposed as image-enhanced endoscopy.5

Although AR is technically complex, the set-up of the system was straightforward. No technical errors were encountered. The registration of the AR views against patient anatomy was rated as uniformly accurate during both dissections. The AR technology was well integrated into the typical set-up for endoscopic sinus surgery.

IGS with AR may offer significant advantages during frontal sinus surgery. The annotated models, created during the pre-dissection phase, provided additional anatomic landmarks in that the models served to highlight anatomy not directly visible on a conventional endoscopic image. These AR views may facilitate more complete and more efficient dissection by facilitating identification of each structure in the frontal recess.

The AR views also provided useful information before starting the dissection. For instance, the frontal recess on each side was cannulated under guidance provided by IGS with AR, as the AR permitted the surgeon to “see” the relevant structures without formally removing the uncinated process or any other tissue. This may have important implications for balloon catheter dilatation of sinus ostia. Outcomes of balloon catheter dilation had been positive in both the operating room8,9 and clinic setting;10 however, some authors have reported less success, particularly at the frontal sinus and maxillary sinus, where cannulation of the sinus ostium may be difficult due to specific anatomic configurations.11 Transillumination, which is commonly performed during balloon catheter dilatation, can only indicate the final destination of the device, but not the path of the device. Incorporation of microsensors, such as the trackable wire that is part of Scopis Navigation system, into balloon catheters may represent a solution to the limitations of transillumination, since such a device may permit real-time feedback to the surgeon about the device tip. In this paradigm, the surgeon would be able to “see” (via AR) the preoperative plan and the instrument tip (via IGS) during the actual cannulation of the target sinus without tissue removal.

An important feature of AR is the ability to highlight relevant information in context. This is best depicted in Figure 3 and 4, where the surgical plan is animated (i.e., changes colors) based upon the position of the instrument tip. Optimization of this workflow may permit greater efficiency and precision during balloon catheter dilatation procedures.

IGS with AR may also function as a “target avoidance” mechanism. Safe sinus surgery, by necessity, involves avoiding inadvertent and potentially catastrophic injury to adjacent structures. AR may mark structures so that their location is clear, before they are exposed during surgery. Figure 5 shows this concept of ‘anti-targeting’ by illustrating the presence of the optic nerve without direct exposure of the optic nerve. The internal carotid artery could be highlighted in a similar fashion. In addition, it may be possible to model the lateral wall and/or roof of the ethmoid to set boundaries for the dissection.

A critical limitation of IGS with AR, as demonstrated in this report, is that all images are still 2D representations, not a holographic 3D image. The AR projections can provide cues that support perceptions of depth, but this is not a true 3D image. The incorporation of true 3D visualization into current AR systems will be an important technological advance. It should be noted that despite the software's sophistication, it will not be a substitute for a competent surgeon's skill and judgement. Rather the software should be viewed as a tool that a competent surgeon will use to achieve a desired surgical objective with greater efficiency and effectiveness.

IGS with AR also represents an important tool for resident and physician education. The technology may facilitate the process of learning to read preoperative CT images and applying that information during surgery. Otorhinolaryngology residents report greater learning with the Building Blocks software, compared with traditional DICOM viewing software that presents CT images in the three orthogonal planes.12 IGS with AR takes this process a step further, and places the models developed during CT review as overlay during dissection. It is anticipated that residents and other learners will readily accept IGS with AR.

Conclusions

IGS with AR was easily deployed in this cadaveric model of endoscopic sinus surgery. Before dissection, the software was used to create annotated models, which were then overlaid onto the actual endoscopic images during the dissection. IGS with AR served to guide traditional dissection of the frontal recess. In addition, IGS with AR provided cues for cannulation of frontal and sphenoid ostia, even without formal ethmoid dissection. Finally, AR may highlight specific ant-targets (i.e., structures to be avoided) and thus enhance surgical safety.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

AL is supported by the Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences, which is funded by National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Award UL1 TR000371 and KL2 TR000370 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Science or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This manuscript was presented in poster format at the spring 2015 meeting of the American Rhinologic Society.

Conflict of Interest

Scopis GmbH (Berlin, Germany) was the sponsor of this investigator-initiated project.

MJC serves as a consultant for JNJ/Acclarent (Menlo Park, CA) and Polyganics BV (Groningen, Netherlands). AL serves as a consultant for ENTvantage (Austin, TX) and GREER (Lenoir, NC). She receives industry research funding from Intersect ENT (Menlo Park, CA), Mallinkrodt Pharmaceuticals (St. Louis, MO), and Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA).

AA and JLB have no financial conflicts of interests to declare.

References

- 1.Ramakrishnan V, Orlandi R, Citardi M, Smith T, Fried M, Kingdom T. The use of image-guided surgery in endoscopic sinus surgery: an evidence-based review with recommendations. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2013 Mar;3(3):236–241. doi: 10.1002/alr.21094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalgorf DM, Sacks R, Wormald PJ, et al. Image-guided surgery influences perioperative morbidity from endoscopic sinus surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2013 Jul;149(1):17–29. doi: 10.1177/0194599813488519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Besharati Tabrizi L, Mahvash M. Augmented reality-guided neurosurgery: accuracy and intraoperative application of an image projection technique. J Neurosurg. 2015 Mar 6;:1–6. doi: 10.3171/2014.9.JNS141001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winne C, Khan M, Stopp F, Jank E, Keeve E. Overlay visualization in endoscopic ENT surgery. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2011 May;6(3):401–406. doi: 10.1007/s11548-010-0507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahidi R, Bax MR, Maurer CR, Jr., et al. Implementation, calibration and accuracy testing of an image-enhanced endoscopy system. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2002 Dec;21(12):1524–1535. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2002.806597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marescaux JDM, Soler L. Augmented reality and minimally invasive surgery. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2013;2(5) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wormald P-J. Three-dimensional building block approach to understanding the anatomy of the frontal recess and frontal sinus. Opereative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2006;17(1):2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss RL, Church CA, Kuhn FA, Levine HL, Sillers MJ, Vaughan WC. Long-term outcome analysis of balloon catheter sinusotomy: two-year follow-up. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2008 Sep;139(3 Suppl 3):S38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolger WE, Brown CL, Church CA, et al. Safety and outcomes of balloon catheter sinusotomy: a multicenter 24-week analysis in 115 patients. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2007 Jul;137(1):10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karanfilov B, Silvers S, Pasha R, et al. Office-based balloon sinus dilation: a prospective, multicenter study of 203 patients. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2013 May;3(5):404–411. doi: 10.1002/alr.21112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomazic PV, Stammberger H, Braun H, et al. Feasibility of balloon sinuplasty in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: the Graz experience. Rhinology. 2013 Jun;51(2):120–127. doi: 10.4193/Rhino12.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agbetoba AL,A, Callejas C, Citardi MJ. Educational untility of advanced 3-dimensional virtual planning in evaluating the anatomical configuration of the frontal recess.. Paper presented at: American Rhinologic Society Spring Meeting; Boston, MA.. 2015. [Google Scholar]