Abstract

Healthcare workers are at increased risk of contracting hepatitis B virus (HBV), particularly in settings of high HBV seroprevalence, such as sub-Saharan Africa. We evaluated HBV knowledge among health-care workers in rural Tanzania by distributing an HBV paper survey in two northern Tanzanian hospitals. There were 114 participants (mean age 33 years, 67% female). Of the participants, 91% were unaware of their HBV status and 89% indicated they had never received an HBV vaccine, with lack of vaccine awareness being the most common reason (34%), whereas 70% were aware of HBV complications and 60% understood routes of transmission. There was a significant difference in knowledge of HBV serostatus and vaccination between participants with a medical background and others, P = 0.01 and 0.001, respectively. However, only 33% of consultants (senior medical staff) knew their HBV serostatus. There was no significant difference between knowledge of HBV transmission routes and occupation. Our study reveals low knowledge of HBV serostatus and vaccination status among hospital workers in Tanzania.

Infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) represents a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with an estimated 350 million people infected, of which the great majority reside in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.1,2 Chronic infection with HBV can lead to cirrhosis and/or liver cancer. The therapeutic resources to battle either cirrhosis or liver cancer in the developing world are scarce, and in sub-Saharan Africa, both conditions carry an extremely high risk of mortality within a year of diagnosis.2,3 It is well known that health-care workers are at increased risk for HBV transmission, largely due to transmission via blood contacting mucosa.4,5 Although the likelihood of chronic disease during contact with HBV in adulthood is low, the probability of being infected through this route is higher than with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).6

The risk of HBV transmission in health-care workers is highest in a setting of high seroprevalence of the virus within a population, such as sub-Saharan Africa, where the overall prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen in blood is > 8%.2,5 In this environment, adherence to universal precautions is critical to prevent HBV transmission. A recent survey regarding occupational exposure in Tanzania observed that nearly half of health-care workers experienced at least one occupational injury within the 12 months preceding the survey.7 In that study, workers were mainly concerned about transmission of HIV. Knowledge of HBV transmission risks in African health-care facilities is important since it is likely to modify health-care workers' adherence to precautions.8

In this study, we aimed to assess the knowledge of HBV serostatus as well as barriers to HBV vaccination in Tanzanian health-care workers. We provided a paper survey to staff in two hospitals in northern Tanzania (Arusha Lutheran Medical Center and Selian Lutheran Hospital, both within the Arusha region of northern Tanzania). Both institutions are considered teaching facilities with residents, interns, and students of different degrees involved in daily activities and care. The survey consisted of nine multiple-choice questions that aimed to determine the participant's knowledge of his or her own HBV serostatus and vaccination status as well as the routes of transmission. Specifically, the survey questioned if the participant had been tested for HBV or vaccinated for HBV (in case of a negative answer, reason for non-vaccination). Transmission and complications of HBV, awareness of increased risk for HBV infection associated with working in a health-care facility, and awareness of family members living with HBV were also included in the survey. The survey was written in English and Swahili (the local language) and distributed among medical and nonmedical staff (laboratory technicians, students, hygiene staff, etc.) to be completed in their language of choice. This initiative was approved by the research committee from both institutions on the basis of care quality improvement and protection of health-care providers. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Paper surveys were distributed among the staff from both institutions with instructions to be returned anonymously in boxes placed around ward areas or personally to resident staff collecting the surveys.

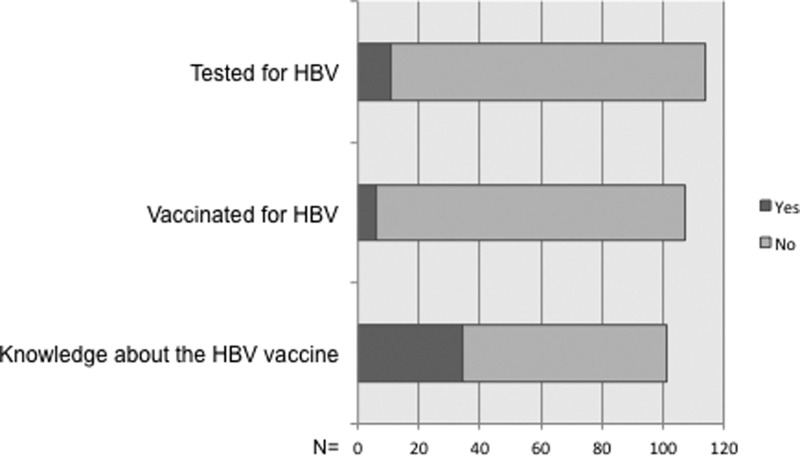

Multivariate analyses were performed using Fisher's exact test and χ2, with a P value < 0.05 considered significant. We collected 114 surveys (of 120 distributed). The mean age of the participants was 33 years (interquartile range = 18–61); 67% were females and 33% males. Of the participants, 70 (61%) completed the survey in Swahili and 44 (39%) in English. A striking 91% of subjects had no knowledge of their HBV serological status and 89% indicated that they had not received a vaccine for HBV (Figure 1 ). Of the 79 participants that provided a reason for non-vaccination, the most common reason was vaccine unawareness (34%), followed by expense of the vaccine (15%) and other reasons (20%). There was a significant difference in knowledge of HBV serostatus and HBV vaccination between participants with a medical background (consultants, interns, etc.) and others (laboratory technicians, hygiene staff, students, etc.), P = 0.01 and 0.001, respectively, for each of the questions. However, only 33% of consultants (senior medical staff with specialty training) knew about their HBV serostatus or had been vaccinated for HBV. Eighty-two participants (70%) indicated an understanding of HBV complications, and 69 participants (60%) responded correctly to questions about HBV transmission routes, such us blood, intercourse, or mother to child (Table 1). There was no significant difference in knowledge of HBV transmission routes or complications between participants who answered in English or Swahili (P = 0.75 and 0.99 for transmission and complications, respectively). As an internal control, we compared correctly answered HBV transmission questions to HBV complication questions. We found that those who chose the correct option regarding transmission route were more likely to have understanding of HBV complications (χ2 = 6.403, P = 0.011)

Figure 1.

Overall responses of questions about hepatitis B.

Table 1.

Awareness, vaccination, and knowledge of HBV based on hospital occupation

| Occupation | Frequency | Tested for HBV | Vaccinated for HBV | Knowledge of HBV transmission* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | ||

| Consultant | 3 | 2 (67) | 2 (73) | 1 (27) | 1 (33) | 1 (34) | 2 (66) |

| Intern/resident/registrar | 11 | 7 (64) | 8 (67) | 3 (33) | 4 (36) | 4 (36) | 7 (64) |

| AMO | 3 | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) |

| AMO student | 7 | 6 (86) | 6 (86) | 1 (14) | 1 (14) | 2 (29) | 5 (71) |

| Nurse | 33 | 32 (97) | 31 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 18 (55) | 15 (45) |

| Nurse student | 22 | 22 (100) | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (32) | 15 (68) |

| Laboratory personnel | 10 | 8 (80) | 10 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (20) | 1 (10) | 9 (90) |

| Other | 24 | 22 (92) | 23 (95) | 1 (5) | 2 (8) | 11 (46) | 13 (54) |

AMO = assistant medical officer; HBV = hepatitis B virus.

Participant responded correctly regarding transmission routes.

It should be noted that depth of HBV transmission knowledge was similar across different hospital occupations with no difference among people with medical, laboratory, or other backgrounds (Fisher's exact test = 9.686, P = 0.183). Despite of the extremely low awareness of HBV status, 97 participants (85%) indicated understanding that working in the health-care setting increased their risk of HBV infection. Regarding knowledge of increased risk of HBV to health-care workers, there was no significant difference whether participants answered in English or Swahili (P = 0.28). Applicants were given the option to answer if they knew a family member that lived with HBV, to which 96% responded negatively. Considering that the prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen in Tanzania is > 8%, it is highly unlikely that only 4% of participants have an HBV-positive family member. This may be a result of the social stigma attached to a blood-borne disease (leading to nondisclosure). Alternatively, lack of diagnostic availability to the overall population could play a role.

Our study shows surprisingly low self-awareness of HBV serostatus and HBV vaccination status with a relatively high level of knowledge about HBV among hospital workers in Tanzania. Other studies in Africa have found a high degree of HBV status unawareness as well, although unawareness levels in those studies seemed less prominent than in our study. In Ethiopia, Abeje and others found that 62% of health-care workers were knowledgeable about the HBV vaccine, but only 5% reported receiving all three doses of the vaccination.9 In Nigeria, Okwara and others found that 29% of health-care workers received vaccination for HBV with 94% being aware of the risks of HBV.10 Similarly, a study from Sudan showed that although over 90% of hospital staff had knowledge about HBV transmission but less than 50% reported having received vaccination against HBV (one or more doses).11 These reports, similar to ours, show alarming evidence that very few health-care workers in sub-Saharan Africa report receiving vaccination against HBV. This is of critical importance since accidental injuries, both percutaneous and mucosal types, are common. Moreover, some reports indicate that sub-Saharan Africa has the highest incidence of occupational exposures in the world.8 This is concerning for all types of blood-borne infections. Generally, health-care facilities in Africa do not routinely offer HBV testing or vaccination to their staff (sometimes vaccine is actually not available) and this could contribute to the lack of knowledge or awareness on HBV status. In this regard, education and information about HBV prevention should be implemented to new employees. In recent years occupational exposures have prompted substantial efforts to be invested in increasing awareness of the risks of HIV infection.12,13 This could be partially influenced by the availability of postexposure prophylaxis for HIV in most referral centers, and consequent awareness of the risk of percutaneous exposure. However, distribution of information and implementation of awareness programs about other diseases, such as HBV, have been significantly scarce. A survey conducted in Rwanda indicated that while only 4.5% of health-care workers had received vaccination against HBV and 11% knew about HBV vaccine, 95% of them had been tested for HIV in the 6 months before the survey.14 As HBV infection is vaccine preventable, more efforts should be devoted to improving awareness of HBV complications and the availability of a vaccine. This is particularly important in countries such as Tanzania, where the health system can provide HBV vaccination at no cost to health-care workers.

One of the limitations of our study is that it relies on self-reported data. This can lead to information bias due to social stigma and recall bias. Our study is also limited to two referral centers in northern Tanzania. Studies are needed in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa to further understand this gap in knowledge and promote awareness programs about HBV among health-care workers.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Jose D. Debes, Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, E-mail: debes003@umn.edu. Johnstone Kayandabila, Department of Medicine, Arusha Lutheran Medical Centre, Arusha, Tanzania, E-mail: johnskay@hotmail.com. Hope Pogemiller, Hospital Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, E-mail: poge0008@umn.edu.

References

- 1.Fattovich G, Bortolotti F, Donato F. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: special emphasis on disease progression and prognostic factors. J Hepatol. 2008;48:335–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trépo C, Chan HL, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2014;384:2053–2063. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cainelli F. Liver diseases in developing countries. World J Hepatol. 2012;4:66–67. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i3.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–662. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Debes JD. Hepatitis B in refugees, guessing the prevalence. Hepatology. 2010;52:802–803. doi: 10.1002/hep.23635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hutin YJ, Hauri AM, Armstrong GL. Use of injections in healthcare settings worldwide, 2000: literature review and regional estimates. BMJ. 2003;327:1075. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7423.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mashoto KO, Mubyazi GM, Mohamed H, Malebo HM. Self-reported occupational exposure to HIV and factors influencing its management practice: a study of healthcare workers in Tumbi and Dodoma Hospitals, Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:276. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sagoe-Moses C, Pearson RD, Perry J, Jagger J. Risks to health care workers in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:538–541. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108163450711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abeje G, Azage M. Hepatitis B vaccine knowledge and vaccination status among health care workers of Bahir Dar City Administration, northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:30. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0756-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okwara EC, Enwere OO, Diwe CK, Azike JE, Chukwulebe AE. Theatre and laboratory workers' awareness of and safety practices against hepatitis B and C infection in a suburban university teaching hospital in Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13:2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakry SH, Mustafa AF, Eldalo AS, Yousif MA. Knowledge, attitude and practice of health care workers toward hepatitis B virus infection, Sudan. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2012;24:95–102. doi: 10.3233/JRS-2012-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertrand JT, Anhang R. The effectiveness of mass media in changing HIV/AIDS-related behaviour among young people in developing countries. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2006;938:205–241. discussion 317–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly JA, Somlai AM, Benotsch EG, Amirkhanian YA, Fernandez MI, Stevenson LY, Sitzler CA, McAuliffe TL, Brown KD, Opgenorth KM. Programmes, resources, and needs of HIV-prevention nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Africa, central/eastern Europe and central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. AIDS Care. 2006;18:12–21. doi: 10.1080/09540120500101757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kateera F, Walker TD, Mutesa L, Mutabazi V, Musabeyesu E, Mukabatsinda C, Bihizimana P, Kyamanywa P, Karenzi B, Orikiiriza JT. Hepatitis B and C seroprevalence among health care workers in a tertiary hospital in Rwanda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015;109:203–208. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trv004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]