Abstract

In 2004, Ethiopia introduced a community-based Health Extension Program to deliver basic and essential health services. We developed a comprehensive performance scoring methodology to assess the performance of the program. A balanced scorecard with six domains and 32 indicators was developed. Data collected from 1,014 service providers, 433 health facilities, and 10,068 community members sampled from 298 villages were used to generate weighted national, regional, and agroecological zone scores for each indicator. The national median indicator scores ranged from 37% to 98% with poor performance in commodity availability, workforce motivation, referral linkage, infection prevention, and quality of care. Indicator scores showed significant difference by region (P < 0.001). Regional performance varied across indicators suggesting that each region had specific areas of strength and deficiency, with Tigray and the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region being the best performers while the mainly pastoral regions of Gambela, Afar, and Benishangul-Gumuz were the worst. The findings of this study suggest the need for strategies aimed at improving specific elements of the program and its performance in specific regions to achieve quality and equitable health services.

Introduction

In 2004, the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) of Ethiopia introduced the Health Extension Program (HEP), a primary care strategy for scaling up essential health promotion, disease prevention, and basic curative services.1 HEP was designed with the most basic health infrastructure in the context of limited resources.2 The national health system was reformed to create a platform for integration and institutionalization of HEP.3 A total of 38,819 female Health Extension Workers (HEWs) with a high school education who received 1-year training on HEP were deployed in over 15,000 newly constructed health posts in rural villages.4 The candidates were recruited from their prospective villages to limit staff turnover and address gender, social, and cultural factors in service provision. HEP comprises 16 service packages covering family health, communicable diseases, and sanitation and hygiene programs. HEWs provide health post and community-based services. The community-based services include provision of household and outreach services and model family package. The model family package delivery involves theoretical and practical training of selected households on the various HEP services. Innovators and early adopters who embrace change opportunities are selected to receive the model family training. To graduate as a model-family, households undergo training on the various HEP services for about 96 hours and are required to implement and adopt the HEP package. The model family households serve as intermediary change agents within their respective neighborhood, while some volunteer model families serve as health promoters to support the community level activities of HEWs. Village health committee and village administration support the implementation of HEP in their respective villages. In line with the country's decentralized governance system, the District Health Office is responsible for management of HEP, while the health centers, each linked to five health posts, provide technical, logistic, and administrative support and serve as referral center.5

HEP has come to be considered the most important institutional framework for achieving the health Millennium Development Goals in Ethiopia.6 It is therefore imperative that HEP should be evaluated to determine whether its objectives are being achieved and to document factors that facilitate or hinder the realization of the objectives.7,8 This requires comprehensive measures that provide evidence on performance of a range of health system elements for decision makers while also promoting good governance and accountability.

The balanced scorecard (BSC), which was originally developed for industry by Kaplan and Norton, has been used in the health sector for integrated performance measurement and strategic management.9–15 The BSC aids in the identification, organization, and linkage of a balanced set of indicators through strategic mapping of performance dimensions.10,14,16 The system facilitates benchmarking for comparison across areas and over time and guides in prioritization of resources. Despite its strategic benefit and wide application in developed countries, the application of scorecard in developing countries has been limited, perhaps due to the unfavorable health-care environment.14,16–21 Among the few developing countries, Afghanistan has been the pioneer in integrating BSC into its national health system.14,16,18

In 2010, FMOH introduced BSC as a planning and management tool and developed its Health Sector Development Program (HSDP IV) based on the BSC framework.4 BSC has been implemented at the FMOH and federal hospitals levels and remains to be cascaded to all levels of the health system. HEP is one of the core components of HSDP, and although studies have documented the performance of the program on individual indicators,22–26 there is limited evidence on integrated performance indices and scoring methodologies.8 We developed a scoring methodology for performance evaluation of HEP based on the BSC approach14,21 and generated performance indices using data obtained from nationwide HEP evaluation survey. It compared performance of various geographic areas and identified health system elements that scored poorly to inform the development of interventions aimed at strengthening the program.

Materials and Methods

Conceptual structure of the BSC.

Health system performance depends on the strength of multidimensional systems including human and physical resources, finance, quality of care, health information, management, and community participation.27 To ensure that all key health system elements were included in the performance measurement, a BSC conceptual framework that captures all the HEP dimensions was designed (Figure 1 ).4,5,28 The framework was used to identify six performance domains (namely, capacity for service provision, financial systems, human resource development, community engagement, service delivery process, and outputs and outcomes) based on the Kaplan and Norton approach and building on the BSC tool that was developed for use in low-income countries by Peters and others.12,14 The BSC included 32 core performance indicators (Table 1), each belonging to one of the six domains. Most indicators were drawn from the FMOH monitoring and evaluation framework,4 while some were included based on other accepted frameworks to balance indicator distribution among the domains.27,29 The indicators were selected based on their importance, scientific soundness, and feasibility.16,30 To clarify the concepts in the framework, the performance dimensions are described below and the underlying indicators are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for comprehensive performance assessment of Health Extension Program in rural Ethiopia.

Table 1.

Core indicators used to develop the BSC for HEP in rural Ethiopia

| Indicators | Description and the factors that went into the indicator |

|---|---|

| Capacity for service provision | |

| HEP staffing | This deals with the number and qualification of service providers at the village level (including HEWs and volunteer health promoters). The standard for HEP staffing at the village level is to have at least two HEWs and one health promoter for every 40 households |

| Health facility infrastructure | The infrastructure index deals with whether the health post has the required infrastructure, facilities, and amenities that enable it to render services as per the standard. It covers the availability of health post building with at least three rooms, the availability of electricity, water and telephone communication, toilet access to patients, and availability of means of transportation |

| Equipment functionality | It measures whether the health post is equipped with the minimum medical equipment required to deliver the HEP services based on the standard. The availability and functionality of the following were considered: examination bed, thermometer, blood pressure apparatus, stethoscope, delivery bed, home delivery kit, neonatal resuscitation mask and bag, baby weighing scale, Salter scale, measuring board, and refrigerator |

| Commodity availability | This covers the availability of essential medical supplies and vaccines required to deliver the basic health services. The following medical supplies were considered: Coartem, oral rehydration salt, contraceptives, ergometrine, iron tablets, folic acid, vitamin A, amoxicillin, RDT for malaria, HIV test kit, and analgesics. The various antigens required for child and mother immunizations were also included |

| Supply management system | This indicator deals with the supply, storage, distribution, and management of medical supplies at the health post, health center, and woreda health office. At the health post, the frequency and waiting time of supply replenishment, the adequacy of supplies, and the ability of HEWs to identify expired drugs were considered. At the health center, availability of adequate stocks of medical supplies (drugs, vaccines, medical equipment, and supplies) for distribution to health posts and availability of adequate and secure storage facility were considered. The availability of medical supplies for all health posts and their sources were considered at the district level |

| HEP guideline and IEC use | It deals with the availability of IEC such as posters and flip charts covering the various HEP service packages and summary charts, and whether the materials were displayed plainly at the health post. It also covers the availability of guidelines for HEP implementation, obstetric care, growth monitoring, and malaria case management |

| HMIS use | The HMIS use indicator deals with the availability and proper use of registers for the various HEP service packages including birth and death registration. It also covers reporting and use of information for decision making |

| Health center capacity | This indicator covers factors that affect the readiness of the health center to serve as referral facility for the health posts. The factors considered included the distance from the health post, availability of service for 24 hours, availability and use of injectable drugs and supplies for emergency obstetric care (such as diazepam, magnesium sulfate, oxytocin, ergometrine, amoxicillin, gentamicin, intravenous infusion, incubator, and forceps and vacuum extractor for assisted delivery), availability of staff who can administer the drugs and perform the procedures, availability of blood transfusion and cesarean section services, and availability of other services that require referral |

| Management capacity | This indicator deals with human resource performance management, planning process, HEP performance monitoring, and partner collaboration. The human resource performance management considered the availability and approaches used to conduct performance assessment of HEWs, ensure adherence to code of conduct, and motivate good performing HEWs. The planning process covered the use of baseline information for planning and the involvement of HEWs in planning process. The HEP performance monitoring covered the involvement of health centers and district health offices, the performance monitoring methods used (such as review of monthly reports, and regular meetings with HEWs), the use of information for decision making, and the comprehensiveness of the indicators used for HEP performance monitoring. The partner collaboration covered the level of support to health posts from district and kebele administrations |

| Supervision capacity | The supervision index covers the human resource capacity for supervision available at the health centers and district health offices, the logistics (supervision guidelines and checklists, transportation and budget for supervision), availability of supervision plan and schedule, performance in supervision (relative to plan and the number of supervisory visits made to health posts over 3 months), the use of appropriate supervision methods and quality of supervision (which is characterized by multidisciplinary team, frequent and regular, person-to-person discussions, discussions with local community and leaders, useful and supportive guidance, and supervisors listen and value HEWs' suggestions), and provision of feedback and follow-up to ensure that correction measures are taken |

| Financial systems | |

| Financing referral system | The financing referral system covers the availability of sustainable arrangements for financing emergency referral services (such as funds/fuel set aside, community insurance scheme, or revolving funds) and availability of barriers for referral system (such as lack or high cost of transportation and cost of services and drugs at referral health facilities) |

| Financing medical supplies | The financing medical supplies cover the availability of adequate funding for medical supplies and whether patients are referred due to lack of basic medical supplies |

| Human resources | |

| HEW knowledge | The HEW knowledge index covers HEW's competence in providing the key HEP service packages. The assessment included knowledge on maternal health (such as on benefits of ANC, signs and monitoring of labor, immediate newborn care, and management (diagnosis and actions taken by HEWs) when a woman comes with heavy bleeding during or after delivery, retained placenta, obstructed labor, infection, eclampsia, severe anemia, and severe malaria); neonatal and child health (including on diagnosis and action taken by HEWs when there is neonatal infection and underweight, acute respiratory infection, diarrhea, and danger signs); family planning (counseling skills regarding the effectiveness, benefits, and risks of all available methods); malaria diagnosis and treatment; and immunization administration schedules |

| In-service training | This indicator covers the provision of in-service training to HEWs on various HEP service packages in the year before the survey and provision of in-service training to HEW supervisors on HEP and supervision techniques |

| HEW satisfaction | This indicator covers the level of HEW satisfaction on salary and benefits, management handling, opportunity with professional development, support and relationship with key stakeholders, and housing condition |

| HEW perception | This indicator deals with perceptions of the HEWs on job responsibilities (including workload and difficulty relative to level of training), remuneration (fairness relative to workload, level of training and workers in other sectors), management (relationship with managers and supervisors and impact of managers on benefits), constraints affecting job performance, social and organizational obstacles, and living conditions |

| Retention of HEWs | It deals with retention of HEWs taking into consideration the number deployed and the number left since HEP started in the district, which was used to generate annual retention rate |

| Service delivery | |

| Service availability | This indicator deals with whether all the HEP service packages are render at the health post |

| Quality of HEP service | This indicator covers the quality of service provision on key aspects of HEP, including cold chain management system that ensures potency of antigens, and important aspects of newborn care services such as handling of umbilical cord, practicing suction of newborn, weighting, drying and wrapping of newborn, and administration of OPV and BCG vaccine at birth |

| Infection prevention | The infection prevention indicator covers availability of infection prevention practices (availability and use of syringes, gloves, and antiseptics), handwashing facility (access to water and soap for patients and availability of handwashing apparatus with tap at the health post), and proper waste disposal (including availability of dust bins and medical waste disposal mechanisms such as pits, burning, or incineration) |

| Referral linkage | The referral linkage index deals with health post, referral health facility, and clients' aspect of the referral system. It considered the type of referral facility, distance, availability of communication and means of transportation, reason for referral, availability of referral forms, functional two-way linkage (referral and feedback), willingness of patients to go to referral health facility, and availability of factors preventing patients from going to referral facility and affecting the referral system (such as poor customer and care services, long waiting time and high cost of service at the referral facility, lack of awareness, distance, and poor road) |

| HEW time use | HEW time use indicator deals with whether HEWs use their time as per the HEP standard. It considered the number of days the health post is opened per week, whether the health post is opened on weekends, number of hours HEWs work daily, and time spent at the health post vs. community level (on average 50% of time for each level). Availability and use of standard manual on apportioning their time among the 16 HEP service packages was also included |

| Model family package delivery | The model family package delivery indicator covers the quality of implementation (relative to the standard procedure) and level of household coverage. The quality of implementation considered the knowledge of HEWs on the standard procedures, actual implementation procedure (number of households enrolled per round, number of hours households were trained before graduation and number of months took to complete the training), training topic selection procedure (priority is given to areas that are easily implementable, do not create conflict with culture, and showed success previously), use of demonstration units for training, process and criteria to determine eligibility for graduation, involvement of key stakeholders (health promoters, kebele council, and HEW supervisor) in training and determining eligibility, and ceremony to celebrate graduation and provide awards. The level of coverage considered number of households graduated assessed relative to the total households in the kebele |

| Community engagement | |

| Awareness and access | The community awareness and access to HEP indicator considered the following factors: awareness about HEP, whether the individual visited HEW in the previous month, whether it was difficult to get to the health post or the HEW and had to wait too long before receiving care during the last visit, and availability of information on the schedule of HEW displayed outside the health post |

| Community and health promoters participation | The community and promoter participation indicator considered the level of participation of various sections of the community in the implementation of HEP as per the standard. The participation of health promoters covered the following factors: number of households assigned, availability of work plan and service registers, whether they prepare monthly reports and participate in monthly review meetings, their level of satisfaction with their role, and the level of support they receive from key partners. It also considered participation of elders, associations, religious and kebele leaders, health promoters, and the community at large in preparing work plan and implementation of HEP |

| Model family engagement | The model family engagement indicator deals with the level of participation of the community in attending training and supporting training of other households (including encouragement and provision of training). It also covered the level of happiness of becoming model family and their interest to serve the community |

| Village health committee | The village health committee functionality indicator covered the availability of health committee, its involvement in planning and implementation and its participation in organizing emergency transportation of referral cases |

| Delivery output and outcome | |

| Maternal and child health output | This indicator deals with the number of key maternal, neonatal, and child health services provided at the health post in the year before the survey assessed relative to the respective population and annual target set by the FMOH. The services included ANC, assisted delivery, immunization, PNC, cases managed (diarrhea, acute respiratory infection, and malaria), nutrition and growth monitoring, and HIV/AIDS education services |

| Family health output | This indicator deals with the number of family planning clients at the health post in the year before the survey assessed relative to the target set by FMOH |

| Satisfaction with services | This indicator measures the level of community satisfaction with the services, specifically on the availability and quality of the various HEP services packages. It covers the satisfaction rate on key maternal and child health services, curative services, sanitation, health education, and model family implementation. It also considered whether the community members would visit again the health post or recommend the same health post to others, and their satisfaction with cleanliness of the health post environment |

| Satisfaction with HEW | This indicator deals with the level of community satisfaction on HEW's technical skills (such as explaining in understandable manner, making helpful suggestions, and discussing treatment options), communication skills (such as caring, friendly, complete explanation, attentive, and respectful) and social skills (such as participation in community events, use local language, good conduct/ethics, and confidentiality of personal information) |

| Satisfaction with HEP | The overall satisfaction with HEP indicator covers overall community satisfaction levels with respect to addressing the health needs of households and the community at large and their level of happiness with the availability of HEP services in their village |

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ANC = antenatal care; BCG = Bacillus Calmette–Guérin; BSC = balanced scorecard; FMOH = the Federal Ministry of Health; HEP = Health Extension Program; HEW = Health Extension Worker; HMIS = health management information system; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; IEC = information, education and communication; OPV = oral polio vaccine; PNC = postnatal care; RDT = rapid diagnostic test.

“Capacity for service provision” domain refers to the preparedness of the system based on the HEP standards for human and physical resources and included 10 indicators. The human resources aspect covered indicators that measure the number and qualification of providers (staffing index) and district managers (management capacity index). Indicators on physical resources included infrastructure index (such as health post, latrine, power, electricity, and water), medical equipment availability and functionality index, commodity index (including drugs, contraceptives, vaccines, and malaria rapid diagnostic tests), and availability of HEP guidelines and use of information, education, and communication (IEC) materials. Other indicators under this domain included the supply distribution system, the health management information system (HMIS), the health center capacity index (measured by the availability of infrastructure, equipment, drugs, and staff for emergency obstetric care), and supervision index (measuring the capacity and quality of supervision).31 These structural elements determine the physical accessibility and capacity to provide services and therefore influence the realization of the full potential of a program.32

“Financial systems” domain refers to the financial input, which is usually inadequate in developing countries but critical to deliver quality services.33 Although finance was often included under capacity for service provision,34 we considered this domain with two indicators covering running costs for medical supplies and emergency referral services including financial barriers in service utilization. User fee was exempted at health posts and was not included.

“Human resources development” domain included five indicators measuring workforce knowledge, in-service training in the past 1 year, perception and satisfaction (regarding working and living conditions), and retention of health workers, which all affect quality of care.35–39

“Community engagement” domain refers to the process of involving the community in decision making and service provision and included four indicators. The basic philosophy of HEP was to ensure community ownership and responsibility for maintaining their own health, which along with the increased expectation for health equity contribute to performance improvement.39–42 In line with the philosophy, HEP involves and encourages households, model families and the community health promoters to bring local knowledge, experiences, and problems to the forefront and take part in decision making.5 The indicators included community awareness and access to HEP, community and volunteer participation index, model family engagement index, and village health committee functionality.

“Service delivery process” perspective relates to the activities carried out to ensure conformity to standard of care including adherence to protocols to meet performance expectations.14,16,43 Six indicators measuring physical accessibility and availability of HEP services, quality of care focusing on reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health (RMNCH), infection prevention practice, referral linkage of health posts with health centers, time use of HEWs, and delivery of model family were included.

“Outputs and outcomes” domain included two indicators on productivity (quantity of maternal and child health services and family planning services), two indicators measuring satisfaction of clients (with services received and HEW performance), and one indicator measuring the overall satisfaction of the community.16,43

Data sources.

The data for generating the performance indices came from an evaluation study of HEP conducted in 2010 by the Center for National Health Development in Ethiopia.

Overview of the HEP evaluation.

The HEP study was conducted in rural villages of the country, where approximately 85% of the Ethiopian population lives. The objectives of the evaluation was to determine the effect of HEP on health outcome measures and to assess the process and degree of implementation of the multidimensional health system components of the program including human resources, physical resources, support and management, and community perspectives. Indicators covering these health system components were drawn from the national monitoring and evaluation framework and other internationally accepted frameworks.29,44,45 The study comprised process and outcome evaluations involving health workers, health facility, and community surveys. The health workers survey targeted volunteer health promoters, HEWs, HEW supervisors, and district managers representing different levels of the health system. The health facility surveys covered health posts and referral health centers. The community survey covered perceptions about and satisfaction with HEP and model family.

Sampling method.

A stratified multistage cluster sampling method with region as strata and district and village as primary and secondary sampling units, respectively, was used to sample the study units. A sampling frame of 591 districts with 13,591 rural villages from the 10 regions was obtained from the Central Statistics Authority. At the first stage of sampling, a total of 71 districts were selected through systematic random sampling with probability proportional to size of regions. At the second stage of sampling, four villages per district were selected using systematic random sampling. The exception was in the mainly pastoral region of Gambela, where eight villages were selected per district with the aim of increasing the sampling units for the process evaluation in pastoralist areas. This sampling procedure resulted in the selection of 312 villages. Health workers, health facilities, and households were sampled at the third stage. Health workers and health facilities were sampled from 298 villages that had implemented HEP, whereas households were sampled from all 312 villages, including 14 that had not implemented the program.

The process evaluation was based on health worker, health facility, and household surveys conducted in the 298 villages. At village level, a health post and all existing HEWs within the 298 villages and all district managers, referral health centers, and HEW supervisors that were responsible for the implementation of HEP in the 298 villages were included in the study without requiring any further sampling procedure. On the basis of this sampling approach, 298 health posts, 399 HEWs, 71 district managers, 135 health centers, and 113 HEW supervisors were included in the survey. Although the target was to randomly sample five volunteer health promoters per village, only 149 villages had at least one health promoter. In villages with five or less health promoters, all were sampled. A total of 615 health promoters were sampled from among 701 that were available in all 298 villages. For the household survey, a cross-sectional sample of 6,750 households at 25 households per village (in Gambela, only 12 households to offset the 2-fold village sampling) was selected from the 298 villages using the random walk method used in the Expanded Program on Immunization cluster survey.46 A total of 10,068 individuals—including a woman from each household and a man from every other household—were sampled for the community perception survey. Among the 298 villages, model family package had been started in 214 villages. Thus, 5,722 households that were sampled from the 214 villages (a subset of the 6,750 households) were targeted for the community survey on model family.

Data collection.

Data were collected from 1,198 key informants (399 HEWs, 615 health promoters, 113 HEP supervisors, and 71 district managers), 433 health facilities (298 health posts and 135 referral health centers), and 10,068 household members. Structured and semi-structured questionnaires, which were adapted from standardized and internationally accepted survey instruments, were used to capture the required information from the different study units.

Health worker survey.

The health workers survey involved in-depth interviews. The health promoters were assessed for their participation in the implementation of HEP, specifically in training of model families, and their perception and satisfaction with their role. HEWs were interviewed on their perception and satisfaction with their working and living conditions, their skills and competence on key maternal, neonatal and child health problems, and their time use practice. Information was also collected on the sociodemographic characteristics of HEWs including age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, language, prior residence, and years of service. HEW supervisors were interviewed on basic information (age, gender, experience, and education), induction and supervision technique training, planning and implementation of supervisory visits including the frequency and supervision methods used, and logistics. Information about the district capacity (human resource, finance, and logistic), recruitment process and attrition rate of HEWs, availability of drugs and supplies for health posts, current practice in technical, logistic, and administrative support of HEP, support from stakeholders, challenges, and perception on the program was collected from district managers.

Health facility survey.

The health facility survey was conducted through interviews and audit (observations and document reviews). It was used to capture information on number and qualification of staffing, whether the staff received in-service training in the past year, the infrastructure conditions, availability and functionality of medical equipment, availability of drugs, vaccines, contraceptives, and other supplies, availability and use of guidelines and information, education and communication materials, the use of HMIS, the supply distribution system, the frequency and quality of supervision received, financing referral system and medical supplies, and referral linkage. Data were also collected on the availability of HEP service packages, quality of service provision, infection prevention practice, model family package delivery, availability and functionality of village health committee, and quantity of services provided in the past 1 year.

Community survey.

The community survey, which was conducted through person-to-person interviews with household members, was used to collect information on the perception and satisfaction of the community regarding the recruitment process of HEWs, behavior and performance of HEWs, accessibility of HEWs and health post, service availability, client centeredness of service, their participation in program implementation, constraints of HEP, and their expectation of the program. Information on the process of model family implementation (selection, training, and graduation), their perception and participation, and readiness of graduated model family to support other households was also collected.

Ethical consideration.

The study received ethical approval from the National Research Ethics Review Committee of the Ethiopian Ministry of Science and Technology and the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University (IRB-AAAC8935). Recruitment of study subjects was carried in person by survey supervisors. Since the study presented no more than minimal risk to subjects, the requirement for signed consent was waived and oral informed consent was obtained from all participants before conducting the interviews. Data collection was carried out in January and February 2010.

Variable selection process.

From the various surveys, the research team selected about 600 eligible variables that fit conceptually to one of the 32 indicators and satisfy the following inclusion criteria: 1) reliability; 2) completeness and extent of missing values; 3) outlier values; and 4) variability. These variables were subjected to expert opinion for possible inclusion in formulating the HEP performance indices. Three experts with good knowledge of HEP and the national health system and who were willing to express their opinions freely were involved in the selection process. After the experts were briefed on the objectives of the research, they were provided with the conceptual framework along with the list of the 32 indicators and 600 variables. The two experts were asked to select and group the variables under the 32 indicators. The third expert was used to resolve disagreements between the two experts. This process resulted in selection of 402 variables for constructing the indicators. The list of variables included under each indicator is shown in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Standardization of variables at the measurement unit.

In preparation for the scoring process, the raw variables were subjected to one or more of the following two procedures. First, the values of all variables were standardized for directionality to ensure that more desirable outcomes receive a higher value and less desirable outcomes receive a lower value. Next, values of variables measured on different scales were normalized to a common scale in the range from 0 to 1 or [0,1]. This procedure was not required for nearly half of the variables, which were dichotomous with value of 0 or 1. Variables with other types of scales such as ordinal and count were subjected to normalization procedures. To normalize an ordinal variable measuring satisfaction level in the range [1,5], one (the minimum in the scale) was subtracted to change the scale into the range [0,4]. It was then divided by 4 (the maximum value in the new scale), which preserved the relative order before transformation. Count data on services provided were transformed into proportion that was achieved relative to target. For example, FMOH has set a target to cover 60% of reproductive age women with contraceptives. The number of contraceptive users in the past year was divided by the target number of women (obtained by taking 60% of the number of all reproductive age women). The proportion relative to the target population was then scaled into the range [0,1], and facilities that achieved or exceeded the target were given a score of 1. The standardization and normalization procedures carried out for each variable are shown in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Scoring of indicators at village level.

Village (kebele), which is the lowest administrative and implementation unit of HEP, was used as the unit of analysis in generating the indicator scores. The analysis involved two steps of aggregation: aggregating observed data by village for each variable (summary statistics by village) and aggregating village variables by indicator for each village (scoring indicators). The first step involves standard analysis of survey data to generate mean or proportion for each variable by village. For example, the village “proportion of individuals who would visit the health post or HEWs again” was generated by dividing “the number of individuals who would visit the health post or HEW again” by “the total number of individuals surveyed” in the village. Similarly, the village “mean satisfaction rate of health promoters with their role” was calculated by averaging the satisfaction rate of all health promoters surveyed in the village. The village means or proportions generated for each variable were used as input variables in the next step.

The indicators were constructed from aggregate sets of variables that measure the same concept to ensure that they were more robust and not driven by the choice of single variable. Thus, the second step involved aggregation of variables along the lines of the conceptual framework to generate scores for the 32 core indicators from the underlying variables. Although various methods are available for weighting and aggregation of variables into a composite indicator, there is no uniformly agreed methodology. We used one of the commonly used methods, which involved assigning equal weights to the group of variables under each indicator and calculating arithmetic average to generate indicator scores. This method was more suitable and appropriate for our work, as it preserves the conceptual framework, involves simple procedures, and preserves the data properties allowing for easier interpretation of the results.47–50

The following three measures of overall performance were also generated from the scores of the 32 core indicators: 1) overall composite score, which was the average score of the core indicators, 2) the percent of core indicators that scored above the bottom quintile, and 3) the percent that scored above the top quintile.14 The results were converted to a percentage score ranging from 0 to 100.

Aggregation of scores over geographic areas.

The village level scores of the 32 core indicators and the three overall performance measures were aggregated to estimate national, regional, and agroecological zone (agrarian, agropastoral, and pastoral) scores for each indicator. To address the complexity of the multistage sampling design, the analysis (aggregation) was undertaken using appropriate weights based on the selection probability at each sampling stage.51 The aggregation analysis at national level involved estimating weighted mean (and standard deviation), median, bottom and top quintiles, and minimum and maximum scores for each indicator. The national level indicator scores were compared against the overall composite score (the mean score of the 32 indicators). Indicators with median values that fell above the top quintile, within the inter-quintile range, and below the bottom quintile of the overall composite score were designated as high, average, and low, respectively. Regional and agroecological zone median scores were estimated for each indicator and compared against national scores. Indicators with scores that fell above the top quintile, within the inter-quintile range, and below the bottom quintile of the national score were designated as good, average, and unsatisfactory, respectively. We used color-coded dashboard to report the performance of the regional indicator scores to facilitate comparison and to easily identify a trend among the various indicators. Indicators that performed good, average, and unsatisfactory were color-coded with green, yellow, and red, respectively. The statistical significance of the difference in the indicator scores by region and agroecological zone was tested using Kruskal–Wallis equality-of-populations rank test.

Results

National level performance.

The national level median scores (Table 2) of the indicators ranged from 37% to 98% showing mixed performance. The indicator scores relative to the overall composite score (with bottom and top quintiles of 57.3% and 70.2%, respectively) showed mixed performance across the domains. Under capacity for service provision, supply distribution system (median, 50%), commodity availability (median, 54%), and infrastructure index (median, 57.1%) scored low, whereas management capacity index (median, 87%) and equipment index (median, 81%) scored high. Financing referral system scored high (median, 75%), whereas financing medical supplies scored low (median, 50%). With respect to human resource, the median scores for HEW satisfaction (49%) and perception (59%) indices were low, while it was high for retention of HEWs (98%). Under the service delivery process, the performance was poor in the areas of infection prevention (median, 47%) and referral linkage (median, 51%), whereas it was high for service availability (median, 75%). Generally, the median scores for indicators under the community engagement were relatively high except for village health committee (50%). Despite the low median scores on maternal and child health (37%) and family planning (46%) output indicators, the scores were high on satisfaction with HEW's performance (87%) and overall satisfaction (89%) of the community. The overall median composite score was 66% (with a range from 45% to 79%). The percent of indicators that achieved the bottom quintile was 78% (with a range from 38% to 97%), while the percent of indicators that achieved the top quintile was 16% (with a range from 0% to 44%).

Table 2.

BSC for health extension program in rural Ethiopia, 2010

| Indicator | N | National mean | Standard deviation | National median | Bottom quintile | Top quintile | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity for service provision | ||||||||

| Staffing index | 298 | 65.8 | 23.0 | 55.5 | 50.0 | 94.8 | 25.0 | 100.0 |

| Infrastructure index | 298 | 60.7 | 18.3 | 57.1 | 42.9 | 71.4 | 14.3 | 100.0 |

| Equipment functionality index | 298 | 82.4 | 15.8 | 81.3 | 68.8 | 93.8 | 50.0 | 100.0 |

| Commodity availability index | 298 | 57.4 | 15.8 | 54.0 | 46.4 | 71.4 | 14.3 | 100.0 |

| Supply distribution system | 298 | 51.3 | 24.7 | 50.0 | 25.0 | 75.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| HEP guidelines and IEC use index | 298 | 79.4 | 13.0 | 75.0 | 66.7 | 91.7 | 41.7 | 100.0 |

| HMIS use | 399 | 76.3 | 18.1 | 73.5 | 56.2 | 89.3 | 25.3 | 100.0 |

| Health center capacity index | 135 | 62.0 | 16.9 | 61.7 | 43.3 | 76.1 | 21.7 | 98.3 |

| Management capacity index | 71 | 87.5 | 11.4 | 86.7 | 77.0 | 91.4 | 50.0 | 100.0 |

| Supervision index | 512 | 68.2 | 8.0 | 68.0 | 59.5 | 73.9 | 44.1 | 87.5 |

| Financial systems | ||||||||

| Financing referral system | 433 | 75.2 | 18.7 | 75.0 | 62.5 | 90.9 | 25.0 | 100.0 |

| Financing medical supply | 433 | 52.1 | 27.1 | 50.0 | 37.3 | 75.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Human resource | ||||||||

| HEW knowledge | 399 | 71.3 | 10.0 | 68.9 | 61.4 | 77.0 | 43.2 | 97.0 |

| In-service training index | 298 | 55.4 | 24.7 | 50.0 | 37.5 | 87.5 | 16.7 | 100.0 |

| HEW satisfaction index | 399 | 47.8 | 13.3 | 49.2 | 38.4 | 59.7 | 7.7 | 87.9 |

| HEW perception index | 399 | 57.7 | 10.7 | 59.0 | 49.0 | 67.6 | 27.1 | 90.3 |

| Retention rate of HEWs | 71 | 93.1 | 10.7 | 97.9 | 92.0 | 99.6 | 26.3 | 100.0 |

| Service delivery process | ||||||||

| HEP package services availability index | 298 | 69.5 | 32.3 | 75.0 | 50.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Quality of RMNCH services | 298 | 62.0 | 11.3 | 60.6 | 53.5 | 68.8 | 27.1 | 100.0 |

| Infection prevention | 298 | 45.1 | 25.3 | 46.7 | 16.7 | 68.3 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Referral linkage index | 433 | 51.0 | 9.9 | 50.6 | 42.8 | 59.4 | 24.6 | 78.4 |

| HEW time use index | 399 | 66.2 | 18.0 | 70.0 | 50.0 | 80.0 | 5.0 | 100.0 |

| Model family delivery index | 298 | 64.6 | 15.4 | 63.8 | 41.6 | 75.6 | 32.4 | 92.2 |

| Community engagement | ||||||||

| Awareness and access to HEP | 10,068 | 72.9 | 16.0 | 76.5 | 60.3 | 87.1 | 20.4 | 100.0 |

| Community and volunteer participation index | 10,683 | 63.3 | 21.5 | 62.2 | 40.0 | 83.3 | 11.1 | 100.0 |

| Model family engagement index | 5,772 | 79.0 | 14.5 | 78.0 | 68.2 | 80.3 | 46.4 | 100.0 |

| Village health committee functionality | 298 | 62.2 | 29.9 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Output and outcome | ||||||||

| Maternal and child health output | 298 | 40.8 | 19.7 | 37.3 | 20.6 | 57.6 | 0.0 | 84.2 |

| Family planning output | 298 | 56.2 | 40.2 | 46.3 | 2.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Satisfaction with services received | 10,068 | 73.8 | 14.4 | 72.9 | 58.9 | 85.1 | 11.7 | 100.0 |

| Satisfaction with HEW performance | 10,068 | 72.0 | 32.1 | 86.7 | 35.3 | 95.2 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Overall community satisfaction | 10,068 | 79.8 | 29.1 | 88.9 | 54.4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Overall performance measure | ||||||||

| Mean score of all indicators (composite score) | 298 | 65.7 | 7.2 | 65.6 | 57.3 | 70.2 | 44.6 | 78.9 |

| % of indicators scored above bottom quintile | 298 | 79.8 | 13.7 | 78.1 | 65.6 | 87.5 | 37.5 | 96.9 |

| % of indicators scored above top quintile | 298 | 17.2 | 9.0 | 15.6 | 9.4 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 43.8 |

BSC = balanced scorecard; HEP = Health Extension Program; HEW = health extension worker; HMIS = health management information system; IEC = information, education and communication; RMNCH = reproductive, maternal, neonatal and child health.

Performance measure by region.

The color-coded dashboard shows the relative performance of each region, which varies by indicator suggesting that each region has specific areas of strength and deficiency (Table 3). Most of the green-coded indicators were found in Tigray and the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples (SNNP), while the majority of the red-coded indicators were found in Gambela and Afar. All indicators in Amhara and Oromia were yellow coded, except one in Amhara (family planning output) that was coded green. The majority of indicators in Benishangul-Gumuz and Somali regions were yellow coded, although, some were green and red coded.

Table 3.

BSC dashboard for the HEP performance measurement by region in rural Ethiopia, 2010

BSC = balanced scorecard; HEP = Health Extension Program; HEW = health extension worker; HMIS = health management information system; IEC = information, education and communication; RMNCH = reproductive, maternal, neonatal and child health; SNNP = the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples.

Interpretation of results should be with precaution due to relatively small sample in smaller regions.

The median scores for all except in-service training index (P = 0.08) showed wide and significant regional variability (P < 0.001). The staff index ranged from 46% in Afar to 86% in SNNP. Equipment availability ranged from 65% in Gambela to 96% in Tigray. HMIS use index was as low as 50% in Gambela and as high as 86% in Tigray. Health center capacity index also varied from 42% in Benishangul-Gumuz to 70% in SNNP, while district management capacity index varied from 67% in Afar to 91% in SNNP. Among the indicators reflecting the service delivery process, wide variation was observed in service package availability index (from 29% in Afar to 81% in SNNP), infection prevention (from 24% in Gambela to 61% in Tigray), and model family package delivery index (from 41% in Gambela to 72% in Tigray). In relation to the community engagement, scores for community participation ranged from 51% in Afar to 76% in Tigray and scores for village health committee ranged from 31% in Afar to 80% in SNNP. Similarly, the scores for maternal and child health output (from 15% in Afar to 51% in SNNP), family planning output (from almost none in Afar and Somali to 71% in Amhara), and overall community satisfaction (from 40% in Benishangul-Gumuz to 88% in Tigray) showed wide variation by region.

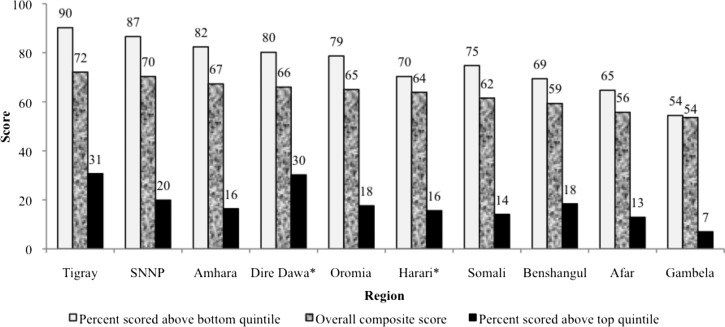

Turning to the overall performance measures, the overall composite score ranged from 54% in Gambela to 72% in Tigray. The score for achieving the bottom quintile varied from 54% in Gambela to 90% in Tigray, while the score for achieving the top quintile varied from 7% in Gambela to 31% in Tigray. Ranking of the regions based on the overall performance measures showed that Tigray ranked at the top followed by SNNP and Amhara regions, while Afar and Gambela ranked last (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Overall performance scores of Health Extension Program by region in rural Ethiopia, 2010.

Performance measure by agroecological zone.

The performance results by agroecological zones are presented in Table 4. Indicators with significantly low score in pastoral areas included staffing, HEW knowledge, infrastructure, equipment index, commodity availability and distribution system, HMIS use, availability of service packages, model family delivery and engagement, and RMNCH outputs. Although not statistically significant, the scores for the capacity of district management, infection prevention, and community participation were also lower in pastoral than in other areas. By contrast, the scores for referral system financing, retention of HEWs, and satisfaction with performance of HEWs were higher in the pastoral than in other areas. The overall composite score for pastoral, agropastoral, and agrarian areas were 59%, 64%, and 65%, respectively. The percent of indicators that achieved the bottom quintile was 66%, 76%, and 79%, while that achieved the top quintile was 12%, 18%, and 17% for pastoral, agropastoral, and agrarian areas, respectively.

Table 4.

BSC for the HEP performance measurement by agroecological zone in rural Ethiopia, 2010

| Indicator | Agroecological zones | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pastoral | Mixed | Agrarian | ||

| Capacity for service provision | ||||

| Staffing index | 53.0 | 56.9 | 66.5 | 0.016 |

| Infrastructure index | 43.9 | 59.0 | 60.4 | 0.011 |

| Equipment functionality index | 62.9 | 81.9 | 82.0 | 0.001 |

| Commodity availability index | 54.8 | 69.9 | 56.3 | 0.000 |

| Supply distribution system | 26.8 | 59.3 | 49.8 | 0.001 |

| HEP guidelines and IEC use index | 73.2 | 79.3 | 77.7 | 0.367 |

| HMIS use | 60.2 | 72.5 | 72.8 | 0.046 |

| Health center capacity index | 60.0 | 63.3 | 60.3 | 0.753 |

| Management capacity index | 73.0 | 81.3 | 84.6 | 0.189 |

| Supervision index | 65.3 | 66.0 | 67.1 | 0.655 |

| Financial systems | ||||

| Financing referral system | 85.0 | 74.8 | 77.1 | 0.150 |

| Financing medical supply | 43.3 | 48.8 | 55.6 | 0.458 |

| Human resource development | ||||

| HEW knowledge | 61.1 | 67.9 | 69.9 | 0.010 |

| In-service training index | 50.5 | 63.5 | 56.5 | 0.451 |

| HEW satisfaction index | 52.8 | 49.4 | 48.8 | 0.532 |

| HEW perception index | 59.0 | 61.4 | 58.1 | 0.421 |

| Retention rate of HEWs | 97.6 | 93.7 | 93.6 | 0.006 |

| Service delivery process | ||||

| HEP package services availability index | 51.8 | 58.3 | 69.3 | 0.045 |

| Quality of RMNCH services | 59.8 | 65.9 | 61.1 | 0.115 |

| Infection prevention | 35.9 | 46.6 | 44.6 | 0.409 |

| Referral linkage index | 52.6 | 50.9 | 50.7 | 0.852 |

| HEW time use index | 60.6 | 70.0 | 65.9 | 0.220 |

| Model family delivery index | 50.6 | 58.6 | 62.0 | 0.013 |

| Community engagement | ||||

| Awareness and access to HEP | 67.3 | 72.2 | 73.1 | 0.124 |

| Community and volunteer participation index | 54.6 | 68.5 | 61.4 | 0.117 |

| Model family engagement index | 63.8 | 82.0 | 74.0 | 0.017 |

| Village health committee functionality | 48.3 | 50.0 | 58.7 | 0.102 |

| Delivery output and outcome | ||||

| Maternal and child health output | 40.0 | 29.5 | 40.0 | 0.038 |

| Family planning output | 45.3 | 24.7 | 51.6 | 0.002 |

| Satisfaction with services received | 68.2 | 69.4 | 72.5 | 0.619 |

| Satisfaction with HEW performance | 80.6 | 67.6 | 68.4 | 0.757 |

| Overall community satisfaction | 78.6 | 73.7 | 77.7 | 0.945 |

| Overall performance measures | ||||

| Mean score of all indicators (composite score) | 58.8 | 63.6 | 64.6 | 0.006 |

| % of indicators scored above bottom quintile | 66.1 | 75.8 | 76.9 | 0.046 |

| % of indicators scored above top quintile | 12.1 | 17.8 | 17.0 | 0.079 |

BSC = balanced scorecard; HEP = Health Extension Program; HEW = health extension worker; HMIS = health management information system; IEC = information, education and communication; RMNCH = reproductive, maternal, neonatal and child health.

Discussion

We developed BSC comprising six domains with 32 indicators for comprehensive performance measurement of the Ethiopian HEP using nationally representative survey data. Despite encouraging reports of positive impact of HEP,8,22–26,52 the findings of this study show major deficiency in its overall performance. The scores across all domains were low, which could be due to their interdependence, where the capacity for service provision and financial systems influence the human resource development, the community engagement and service provision process that in turn affect the output and outcome dimension.6,32,39 Although it used few indicators, a study by Sebastian and others found that the performance of HEP was poor and that there was inefficiency in productivity relative to available resources, which is an indication that multidimensional factors other than inputs affect the outcome of the program.8 The BSC approach used in this article helped identify health system elements with relatively poor performance.14,16 The performance of the program was low in the areas of infrastructure, commodity (including financing, distribution and availability), satisfaction and perception of HEWs, infection prevention, referral linkage, and service quality and outputs. These elements are interconnected, where gaps in human and physical resources contribute to poor quality of care leading to low service utilization and output, which could be among the factors contributing to the low HEP service utilization reported in a study conducted by Kelbessa and others.52 Satisfactory performance was observed in the areas of equipment availability, use of guidelines, availability and use of information, education and communication materials, referral system financing, HEW retention, as well as the community awareness, engagement, and satisfaction, which is consistent with findings of other studies conducted in various regions of the country.52–54 It is interesting to note that the HEW retention was high despite the low satisfaction and perception, which may be due to the HEWs being recruited from the village where they were deployed as well as the fact that the program was new with HEWs having served only for a few years. Another possible explanation for the high retention despite the low satisfaction could be that HEWs, unlike other health professionals such as nurses, have limited prospects to working in better paying private health sector jobs forcing them to stay although their intention to leave could be high. Given that job satisfaction is one of the factors influencing health worker retention, the unexpected finding of this article suggest the need for further studies on HEW intentions regarding HEP to inform the design of strategies aimed at positively influencing the same to ensure high retention.

The findings showed significant difference in the performance of HEP by region and agroecological zone. Overall performance was poor in pastoral regions of Gambela, Afar, Somali and Benishangul-Gumuz, consistent with the poor health indicators reported in these regions.45 The poor performance was primarily driven by poor performance in staffing, HEW knowledge, infrastructure, equipment, commodity availability and distribution, HMIS use, service package availability, model family delivery and engagement, and service output. The remote and harsh climatic conditions and the highly mobile and geographically dispersed settlement coupled with poor infrastructure and lack of social services could be the major factors contributing to the low performance of HEP in these regions.55 Pastoralists have many special health needs that could not be completely met by the largely static health post–based HEP strategy, thereby resulting in poor performance of the program in such settings.3,56 In recognition of HEP's inadequacy in pastoral areas, FMOH took steps to redesign the program. FMOH and pastoral regions in collaboration with research institutions are undertaking research projects to understand the pastoral context and generate information to inform the design of the most appropriate health services and effective service delivery models.

Limitations.

First, although fewer indices were presented in the BSC, the burden of data collection poses an operational challenge. Thus more effort should be made to minimize the data requirement by selecting the most important and reliable predictors of performance. Second, equal weights were assigned to individual variables, while their actual contribution to specific indicators might be different, which might affect the reliability and validity of the resulting scores. However, we used the equal weighting approach because of the lack of statistical or empirical evidence for using a different approach. Further research is needed to understand the relative importance of variables used in computing the scores, the effect of assigning equal or different weights, and the consequences of dropping non-important variables to minimize data requirements. Third, indicator scores were generated using arithmetic average, which may produce less valid results compared with other methods such as the principal component analysis. However, the use of averaging is more suitable for our study because of the following advantages over the other methods: it is easy to compute, the scores retain the scale metric allowing for easier interpretation, it allows comparability across indicators, it preserves the dimensions of the conceptual framework, and scores are more stable across samples (more reliable). Fourth, the indicators under the output and outcome domain were limited to health post productivity. Future work should incorporate outcome and impact indicators to ensure comprehensive measurement. The findings of this study provide opportunities for further research on the methodology and list of indicators to optimize and make the BSC tool useful and acceptable to policy makers and stakeholders.

Conclusion

The BSC tool was used to determine the performance of the health system components of HEP. Despite the need to optimize the tool, using BSC revealed three major findings: 1) deficiency in the overall performance of HEP, and specifically, in the areas of commodities, workforce motivation, referral linkage, and quality of care including infection prevention; 2) performance of regions varied by indicator suggesting that each region has specific areas of strength and deficiency; and 3) the performance of the mainly pastoral regions was poor, especially in the areas of workforce capacity, infrastructure, equipment and commodity availability, HMIS use, HEP service availability, model family, and outputs. The low performance on certain program and geographic areas could limit HEP in achieving its objectives and goals. The findings of this study suggest the need for strategies aimed at improving specific elements of the program and its overall performance in specific regions, thereby ensuring quality and equitable health services and realizing its objectives and goals. Although recognizing the need to address the operational challenges, using the BSC tool to measure the performance of a program can guide resource allocation (targeting specific areas lagging behind) and provide reference point for historical monitoring and geographic area comparison of performance.14,16,18

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the input of professionals who provided expert opinion in the design of the balanced scorecard tool and selection of the underlying indicators. We would like to thank the survey coordinators, field workers, and study participants including health workers and managers and the community members. We also thank the Federal Ministry of Health for allowing the health managers, health facilities, and health workers to participate in the study.

Disclaimer: The sponsors had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial support. This study was made possible by the financial support from the Blaustein Foundation and the funding provided by the UNICEF and WHO Ethiopia country offices for the 2010 National Evaluation of HEP.

Authors' addresses: Hailay D. Teklehaimanot and Awash Teklehaimanot, Earth Institute at Columbia University, New York, NY, and Center for National Health Development in Ethiopia, Columbia University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, E-mails: hailaycnhde@ethionet.et and thawash@ei.columbia.edu. Aregawi A. Tedella and Mustofa Abdella, Center for National Health Development in Ethiopia, Columbia University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, E-mails: aregawiak@yahoo.com and mustofa.abdella@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.FMOH . Health Sector Development Plan, 2005/6–2010/11, Mid-Term Review. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Ministry of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan M. Return to Alma-Ata. Lancet. 2008;372:865–866. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teklehaimanot HD, Teklehaimanot A. Human resource development for a community-based health extension program: a case study from Ethiopia. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:39. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.FMOH . Health Sector Development Program (IV), 2010/11–2014/15. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Ministry of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.FMOH . Health Extension Program in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Ministry of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Travis P, Bennett S, Haines A, Pang T, Bhutta Z, Hyder AA, Pielemeier NR, Mills A, Evans T. Overcoming health-systems constraints to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. Lancet. 2004;364:900–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16987-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavis JN, Posada FB, Haines A, Osei E. Use of research to inform public policymaking. Lancet. 2004;364:1615–1621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17317-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sebastian MS, Lemma H. Efficiency of the health extension programme in Tigray, Ethiopia: a data envelopment analysis. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2010;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gauld R, Al-wahaibi S, Chisholm J, Crabbe R, Kwon B, Oh T, Palepu R, Rawcliffe N, Sohn S. Scorecards for health system performance assessment: the New Zealand example. Health Policy. 2011;103:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inamdar N, Kaplan RS, Bower M. Applying the balanced scorecard in healthcare provider organizations. J Healthc Manag. 2002;47:179–195. discussion 195–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inamdar SN, Kaplan RS, Jones ML, Menitoff R. The Balanced Scorecard: a strategic management system for multi-sector collaboration and strategy implementation. Qual Manag Health Care. 2000;8:21–39. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200008040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan RS, Norton DP. The balanced scorecard—measures that drive performance. Harv Bus Rev. 1992;70:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klassen A, Miller A, Anderson N, Shen J, Schiariti V, O'Donnell M. Performance measurement and improvement frameworks in health, education and social services systems: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22:44–69. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzp057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters DH, Noor AA, Singh LP, Kakar FK, Hansen PM, Burnham G. A balanced scorecard for health services in Afghanistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:146–151. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.033746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zelman WN, Pink GH, Matthias CB. Use of the balanced scorecard in health care. J Health Care Finance. 2003;29:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edward A, Kumar B, Kakar F, Salehi AS, Burnham G, Peters DH. Configuring balanced scorecards for measuring health system performance: evidence from 5 years' evaluation in Afghanistan. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan GJ, Parco KB, Sihombing ME, Tredwell SP, O'Rourke EJ. Improving health services to displaced persons in Aceh, Indonesia: a balanced scorecard. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:709–712. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.064618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen PM, Peters DH, Niayesh H, Singh LP, Dwivedi V, Burnham G. Measuring and managing progress in the establishment of basic health services: the Afghanistan health sector balanced scorecard. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2008;23:107–117. doi: 10.1002/hpm.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabbani F, Jafri SM, Abbas F, Pappas G, Brommels M, Tomson G. Reviewing the application of the balanced scorecard with implications for low-income health settings. J Healthc Qual. 2007;29:21–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2007.tb00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabbani F, Jafri SM, Abbas F, Shah M, Azam SI, Shaikh BT, Brommels M, Tomson G. Designing a balanced scorecard for a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan: a modified Delphi group exercise. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2010;25:74–90. doi: 10.1002/hpm.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ten Asbroek AH, Arah OA, Geelhoed J, Custers T, Delnoij DM, Klazinga NS. Developing a national performance indicator framework for the Dutch health system. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16((Suppl 1)):i65–i71. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Datiko DG, Lindtjorn B. Health extension workers improve tuberculosis case detection and treatment success in southern Ethiopia: a community randomized trial. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karim AM, Admassu K, Schellenberg J, Alemu H, Getachew N, Ameha A, Tadesse L, Betemariam W. Effect of Ethiopia's health extension program on maternal and newborn health care practices in 101 rural districts: a dose-response study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King JD, Endeshaw T, Escher E, Alemtaye G, Melaku S, Gelaye W, Worku A, Adugna M, Melak B, Teferi T, Zerihun M, Gesese D, Tadesse Z, Mosher AW, Odermatt P, Utzinger J, Marti H, Ngondi J, Hopkins DR, Emerson PM. Intestinal parasite prevalence in an area of Ethiopia after implementing the SAFE strategy, enhanced outreach services, and health extension program. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medhanyie A, Spigt M, Kifle Y, Schaay N, Sanders D, Blanco R, Geertjan D, Berhane Y. The role of health extension workers in improving utilization of maternal health services in rural areas in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:352. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yitayal M, Berhane Y, Worku A, Kebede Y. The community-based Health Extension Program significantly improved contraceptive utilization in West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:201–208. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S62294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kringos DS, Boerma WG, Hutchinson A, van der Zee J, Groenewegen PP. The breadth of primary care: a systematic literature review of its core dimensions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:65. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kringos DS, Boerma WG, Bourgueil Y, Cartier T, Hasvold T, Hutchinson A, Lember M, Oleszczyk M, Pavlic DR, Svab I, Tedeschi P, Wilson A, Windak A, Dedeu T, Wilm S. The European primary care monitor: structure, process and outcome indicators. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kruk ME, Freedman LP. Assessing health system performance in developing countries: a review of the literature. Health Policy. 2008;85:263–276. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall M. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:358–364. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.4.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosch-Capblanch X, Garner P. Primary health care supervision in developing countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:369–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brugha R, Starling M, Walt G. GAVI, the first steps: lessons for the Global Fund. Lancet. 2002;359:435–438. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07607-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.WHO . Macroeconomics and Health: Investing in Health for Economic Development. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. Report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donabedian A. Methods for deriving criteria for assessing the quality of medical care. Med Care Rev. 1980;37:653–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen LC. Striking the right balance: health workforce retention in remote and rural areas. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:323. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.078477. A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitaw Y, Ye-Ebiyo Y, Said A, Desta H, Teklehaimanot A. Assessment of the training of the first intake of health extension workers. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2007;21:232–239. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mutale W, Ayles H, Bond V, Mwanamwenge MT, Balabanova D. Measuring health workers' motivation in rural health facilities: baseline results from three study districts in Zambia. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:8. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsen OE, Ndeki S, Norheim OF. Human resources for emergency obstetric care in northern Tanzania: distribution of quantity or quality? Hum Resour Health. 2005;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yitayal M, Berhane Y, Worku A, Kebede Y. Health extension program factors, frequency of household visits and being model households, improved utilization of basic health services in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:156. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banteyerga H. Ethiopia's health extension program: improving health through community involvement. MEDICC Rev. 2011;13:46–49. doi: 10.37757/MR2011V13.N3.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruni RA, Laupacis A, Martin DK. University of Toronto Priority Setting in Health Care Research Group Public engagement in setting priorities in health care. CMAJ. 2008;179:15–18. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosato M, Laverack G, Grabman LH, Tripathy P, Nair N, Mwansambo C, Azad K, Morrison J, Bhutta Z, Perry H, Rifkin S, Costello A. Community participation: lessons for maternal, newborn, and child health. Lancet. 2008;372:962–971. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arah OA, Westert GP, Hurst J, Klazinga NS. A conceptual framework for the OECD Health Care Quality Indicators Project. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18((Suppl 1)):5–13. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzl024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260:1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.FMOH . Health and Health Related Indicators of Ethiopia. Addis Abab, Ethiopia: Federal Ministry of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.WHO . Immunization Coverage Cluster Survey: Reference Manual. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. WHO/IVB/04.23. [Google Scholar]

- 47.DiStefano C, Zhu M, Mindrila D. Understanding and using factor scores: considerations for the applied researcher. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2009;14:1–11. http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=14&n=20 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh RP, Nath S, Prasad SC, Nema AK. Selection of suitable aggregation function for estimation of aggregate pollution index for river Ganges in India. J Environ Eng. 2008;134:689–701. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grice JW, Harris RJ. A comparison of regression and loading weights for the computation of factor scores. Multivariate Behav Res. 1998;33:221–247. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3302_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jollands N, Lermit J, Patterson M. The Usefulness of Aggregate Indicators in Policy Making and Evaluation: A Discussion with Application to Eco-Efficiency Indicators in New Zealand. 2003. http://een.anu.edu.au/wsprgpap/papers/jolland1.pdf Available at.

- 51.Wooldridge JM. Cluster-sample methods in applied econometris. Am Econ Rev. 2003;XCIII:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelbessa Z, Baraki N, Egata G. Level of health extension service utilization and associated factors among community in Abuna Gindeberet District, West Shoa Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:324. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Negusse H, McAuliffe E, MacLachlan M. Initial community perspectives on the Health Service Extension Programme in Welkait, Ethiopia. Hum Resour Health. 2007;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Birhanu Z, Godesso A, Kebede Y, Gerbaba M. Mothers' experiences and satisfactions with health extension program in Jimma zone, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:74. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.WISP . Pastoralism in Ethiopia: Its Total Economic Values and Development Challenges. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: SOS Sahel Ethiopia, World Initiative for Sustainable Pastoralism; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dubale T, Mariam DH. Determinants of conventional health service utilization among pastoralists in northeast Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2007;21:142–147. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.