Abstract

Bone metastases is a well described event in the natural history of thyroid cancers and has the potential to severely impact the quality of life by causing pain, fractures and spinal cord compression. Follicular thyroid carcinomas have a greater propensity for distal metastasis than papillary and anaplastic thyroid carcinomas. The most common sites of skeletal metastasis among thyroid cancer patients are femur followed by humerus, pelvis, radius, and scapula. Clavicle metastasis at initial presentation is exceedingly rare. Although many studies have examined the various prognostic factors for patients with bony metastases from thyroid cancers, very few have actually evaluated the effects of surgical management. We present an unusual case of metastatic papillary carcinoma thyroid presenting with clavicle metastasis and review the role of surgical management of bone metastases. Clavicular resection as a part of the management of metastatic papillary carcinoma thyroid has, to the best of our knowledge never been reported before.

Keywords: Clavicle metastasis, Bone metastasis, Papillary thyroid cancer, Surgery

Introduction

Distant metastases, at initial diagnosis, are reported to occur in about 1–3 % of patients with well differentiated thyroid carcinomas and in about 7–23 % during the course of the disease process [1]. Bone has been reported to be the second most common site of distant metastasis after lung [2], the most common skeletal sites being femur followed by humerus, pelvis, radius, and scapula. Clavicle metastasis at initial presentation is rare. Although many studies have examined the various prognostic factors for patients with bony metastases from thyroid cancers, very few have actually evaluated the effects of surgical management [2]. We recently got to treat an interesting case of clavicle metastasis in a 52-year-old male patient with papillary thyroid cancer and discuss this atypical skeletal event.

Case Report

A 52-year-old male patient, with no comorbidities was referred to our centre following an incisional biopsy for a swelling overlying the medial end of the right collar bone. His presenting features to the referring centre were a right lower neck swelling and a low back pain of 6 months duration. Clinical examination revealed a 7 cm horizontal scar overlying a 5x4cm tender bony swelling with an ill-defined soft tissue component, arising from the medial end of the right clavicle which was seen in contiguity with the right lobe of the thyroid gland. Examination of the neck further revealed a 4.5x4cm well circumscribed nodule in the left lobe of the thyroid gland, which was confirmed by reviewing the CT scan of the neck done at the referral centre (Fig. 1a and b). A review of the incisional biopsy slides and aspiration cytology was suggestive of a metastatic papillary carcinoma thyroid. A bone scan revealed an increased uptake in the right clavicle and D10 vertebra (Fig. 2). The intensity of his back pain increased while on evaluation and was associated with lower limb weakness. The finding of an impending spinal cord compression at the D10 level in an MRI scan prompted an emergency spinal decompression surgery. A D9-D10 costo-tranversectomy and an excision of the associated para-spinal soft tissue component was done, the final histopathology of the same was also suggestive of a metastatic papillary carcinoma thyroid. He was subsequently taken up for thyroid surgery. The thyroidectomy scar was dropped down to merge with the prior incisional biopsy scar and an en bloc excision of the medial half of the right clavicle was done along with a total thyroidectomy and a central compartment neck dissection (Fig. 3d). The final histopathology confirmed the presence of papillary carcinoma thyroid with extra-thyroidal extension and metastatic involvement of the clavicle (Fig. 4) which was extending up to the inked margin. Adjuvant External beam radiation was given to the D10 vertebra. (30 Gray) A subsequent whole body Iodine-131 scan revealed minimal residual thyroid uptake along with uptakes in the dorsal vertebrae. The patient subsequently underwent I-131 ablation twice with 200 milli-curies of Radio Iodine. He is on follow up on thyroxin suppression for close to one and a half years following his initial surgery with a good quality of life and no functional disability.

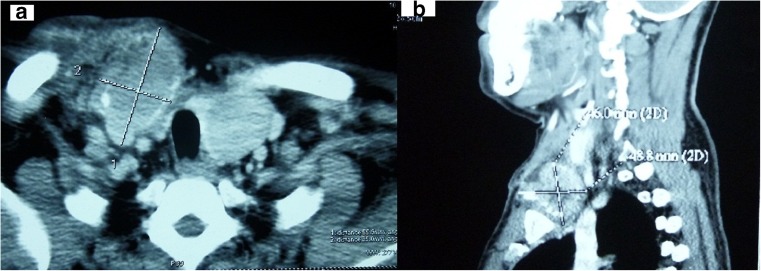

Fig. 1.

ab Contract enhanced CT scan of the neck showing a 5.6 × 3.5 cm lytic lesion arising from the medial half of the right clavicle with an associated 3.5 × 3.6 cm nodule in relation to the left lobe of thyroid

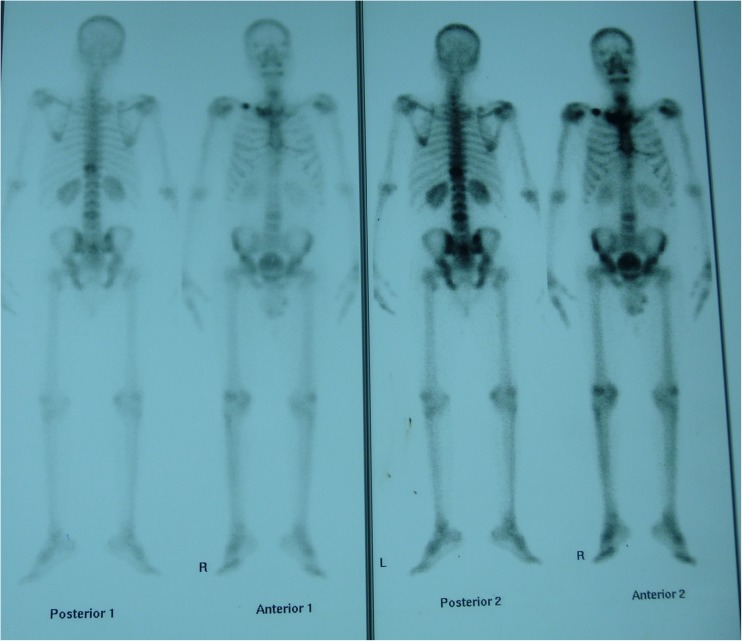

Fig. 2.

Bone scan showing an increased uptake in the right clavicle and also in the region of the D10 vertebra

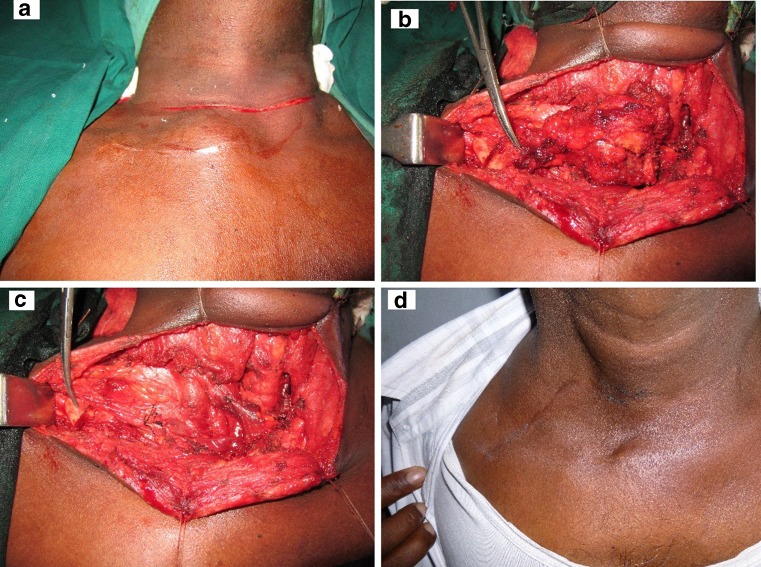

Fig. 3.

a Clinical photograph at presentation. b Intraoperative photograph showing an en bloc excision of the tumor bearing medial half of right clavicle with the total thyroidectomy. c Intraoperative photograph following the en bloc excision. d Post operative photograph following completion of surgery and radiotherapy to the neck

Fig. 4.

H&E 10X- Showing features suggestive of papillary carcinoma thyroid with infiltration of the clavicle

Discussion

Bone metastases are commonly attributed to primary tumours arising from the prostate, breast, lung and kidney. Bone has been reported to be the second most common site of distant metastasis among patients with well differentiated thyroid cancers and its incidence ranges from 1 % to more than 40 % [3]. Follicular carcinomas show a greater propensity for distal metastasis (7–28 %) than papillary (1.4–7 %) and anaplastic thyroid carcinomas. Nonetheless, some studies have reported a higher relative incidence of papillary carcinoma giving rise to bone metastases [3]. Patients with bone metastasis from thyroid cancers generally have better survival (10-year survival rates ranging from 13 to 21 %) than some other primary carcinomas that more frequently metastasize to bone [4].

The clavicle forms the anterior portion of the shoulder girdle and is considered to be embryologically unique as it is the first bone in the human body to ossify. However, from the oncological standpoint, the clavicle is a rare primary site for malignancy, metastatic involvement of the clavicle is even rarer (0–15 %) and precious little is known about its management [5]. A clinician evaluating a patient with pain around the clavicle will only rarely encounter a bony tumor, compared to the vast majority of complaints originating as a result of arthritis, ligamentous injuries and fractures. Clavicular lesions in patients older than 50 years should be considered as malignant unless proven otherwise [5].

The pathogenesis of well differentiated thyroid cancers and its promulgation to bone has yet to be fully elucidated; the individual prognosis depends upon age at diagnosis of metastasis, tumour burden and the number of bony metastases. A great majority of the appendicular skeletal metastasis from thyroid cancers can be effectively managed by external beam radiation therapy or radioactive iodine ablations [4, 6], however, some of the bony metastasis require surgical intervention due to the associated symptoms and fracture risk [4, 7]. Surgical intervention is usually recommended for isolated, solitary and accessible metastases [8]. In patients with multiple site involvement, the role of metastectomy is less well understood. There have been reports that have shown that removal of up to five bony metastases can be associated with improved survival and quality of life [6, 9, 10]. Apart from the above rationale, surgical resection of the clavicle was contemplated in our patient in view of the associated pain and more importantly its close proximity with the thyroid primary.

In conclusion, in the absence of firm management guidelines clinicians should use their judgment in choosing patients for surgical management of bony metastasis from thyroid cancers.

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

None declared

References

- 1.Karl W, Shen-Mou H, Tien-Shang H, Rong-Sen Y. Thyroid carcinoma with bone metastases: a prognostic factor study. Clin Med Oncol. 2008;2:131–136. doi: 10.4137/cmo.s333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muresan MM, Olivier P, Leclère J, Sirveaux F, Brunaud L, Klein M, Zarnegar R, Weryha G. Bone metastases from differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:37–49. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tickoo SK, Pittas AG, Adler M, Fazzari M, Larson SM, Robbins RJ, Rosai J. Bone metastases from thyroid carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1440–1447. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-1440-BMFTC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wexler JA. Approach to the thyroid cancer patient with bone metastases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2296–307. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suresh S, Saifuddin A. Unveiling the ‘unique bone’: a study of the distribution of focal clavicular lesions. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:749–756. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durante C, Haddy N, Baudin E, Leboulleux S, Hartl D, Travagli JP, Caillou B, Ricard M, Lumbroso JD, De Vathaire F, Schlumberger M. Long-term outcome of 444 patients with distant metastases from papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma: benefits and limits of radioiodine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2892–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stojadinovic A, Shoup M, Ghossein RA, Nissan A, Brennan MF, Shah JP, Shaha AR. The role of operations for distantly metastatic well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Surgery. 2002;131:636–43. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.124732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Proye CA, Dromer DH, Carnaille BM, Gontier AJ, Goropoulos A, Carpentier P, Lefebvre J, Decoulx M, Wemeau JL, Fossati P. Is it still worthwhile to treat bone metastases from differentiated thyroid carcinoma with radioactive iodine? World J Surg. 1992;16:640–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02067343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zettinig G, Fueger BJ, Passler C, Kaserer K, Pirich C, Dudczak R, Niederle B. Long-term follow-up of patients with bone metastases from differentiated thyroid carcinoma – surgery or conventional therapy? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;56:377–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernier MO, Leenhardt L, Hoang C, Aurengo A, Mary JY, Menegaux F, Enkaoua E, Turpin G, Chiras J, Saillant G, Hejblum G. Survival and therapeutic modalities in patients with bone metastases of differentiated thyroid carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;86:1568–73. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]