Abstract

Prognostic role of surgical resection of the primary tumor and baseline CEA among patients with synchronous stage IV colorectal cancer (CRC) remains an area of debate. The objective of this study was to determine the prognostic value of baseline CEA and surgical resection of the primary among patients with synchronous stage IV CRC in the era of modern chemotherapy and biologic therapy. The Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Registry was searched to identify patients with synchronous stage IV CRC diagnosed between 2004 and 2009. Colorectal-cancer-specific survival (CCS) was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier product limit method. Cox models were fitted to assess the multivariable relationship of various patient and tumor characteristics and CCS. Three hundred thirty-three thousand, three hundred ninety nine patients were identified in the SEER registry. Median CCS among patients with their primary tumor removed was 21 M vs. 7 M (primary intact) respectively (p < 0.001). Median CCS among patients who had an elevated vs. non-elevated baseline CEA level was 14 M vs. 24 M respectively (p < 0.0001). By multivariable analysis, patients with an elevated baseline CEA had a 56 % increased risk of death from CRC compared to those with a non-elevated CEA level (HR = 1.56, 95%CI 1.47–1.65, p < 0.0001). Similarly patients who underwent surgical resection of the primary tumor had a 33 % decreased risk of death from CRC compared to those who did not (HR = 0.61, 95%CI 0.54–0.69, p < 0.0001). In our review of this large population SEER based study, an elevated baseline CEA level and surgical resection of the primary tumor among patients with synchronous stage IV CRC appeared to impact survival outcomes. Prospective validation of these results in a surgically unresectable patient population will be required.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, SEER, CEA, Stage IV, Surgery

Introduction

In 2012, approximately 143,460 new cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) will be diagnosed in the United States with an associated 51,690 deaths attributable to this disease [1]. Approximately, 20 % of patients present with synchronous stage IV disease and 50 % of patients with early stage CRC will experience a recurrence without adjuvant therapy [2]. With the introduction of modern chemotherapy, targeted biological agents and improved palliative care there is no doubt that the survival of patients with metastatic CRC has improved with a 5-year overall survival reported to rang from 10 to 20 % [3–5] and median overall survival reported to reach 31 months among those patients who are treated with these therapies [6].

Patients with synchronous stage IV CRC represents a unique cohort where the primary tumor is intact in the setting of metastatic disease. Surgical resection of the primary tumor in this cohort has been a matter of debate where results of retrospective studies have advocated both for [7–9] and against [10–12] surgical resection. One indication for the upfront resection of the primary is in the setting of an urgent need to abate symptoms of obstruction, perforation or intractable bleeding. A second indication would be to attain a possible cure if the primary tumor and all measurable metastatic disease are resected. Metastatectomy is restricted to a fraction of patients (<20 %) as the majority of patients with synchronous stage IV CRC have distant metastatic disease that cannot be resected at the time of presentation [13]. Hence, in this setting, resection of an asymptomatic primary tumor is controversial given the potential morbidity and also the delay of subsequent systemic chemotherapy. Interestingly, in the United States, despite no clear answer about a positive impact on overall survival it is reported that more than half of patients with synchronous metastatic disease undergo resection of their primary disease [8].

Several studies have demonstrated baseline CEA to be both a significant prognostic factor [14–17] as well as an indicator of recurrence and therapeutic effect among patients with CRC [18, 19]. Granted CEA is not elevated in approximately 15 % of all metastatic colorectal cancer patients. However most studies that have reported on the prognostic role of baseline CEA and surgical resection of the primary tumor in patients with synchronous stage IV CRC have relied on data derived from an era preceding the widespread use of biological agents. Using data derived from Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Registry (SEER) we sought to determine the individual prognostic value of baseline CEA and surgical resection of the primary tumor among patients with synchronous stage IV CRC treated in the era of biologic therapy. The prognostic role of baseline CEA among patients who undergo surgery of their primary in this cohort was also explored.

Patients and Methods

Patient Population

Data was derived from the National Cancer Institute’s SEER 18 registry databases (released in April 2012). The registry covers approximately 26 % of the population of the United States [20]. Search criteria were restricted to patients with pathologically confirmed invasive synchronous stage IV CRC (AJCC 6th edition) who were diagnosed between 2004 and 2009. Patients with more than one primary were excluded. Variables relating to patient and tumor characteristics were extracted including surgery of the primary tumor and baseline CEA level. CEA was grouped as positive, normal (coded in SEER as “negative/normal” and “borderline” categories) and unknown. SEER CEA groups are based on documented physicians’ interpretation of a CEA level or on reference values provided by the test laboratory reporting the CEA level.

Statistical Analysis

Survival end points were computed using the Kaplan-Meier product limit method and compared across groups using the log rank statistic. CRC-specific-survival (CCS) was computed from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from CRC with patients either alive at the date of last follow-up or who had died of other causes being censored. Overall survival was computed from the date of diagnosis of CRC to the date of death from any cause or last follow-up with patients still alive at last follow up being censored. Cox proportional hazards model were then fitted to look at the association of each of the survival end points with both surgery of primary and baseline CEA level after adjusting for a number of patient and tumor characteristics. The variables included in these models were based on clinical significance regardless of univariate statistical significance. The models were adjusted for the18 SEER registries. The models were additionally repeated and stratified by CEA level (elevated and normal) to determine the prognostic significance of surgery of the primary tumor among the two groups. P-values were two-sided and a value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses for this study were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute,Cary,NC).

Results

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the patient and tumor characteristics. The final analysis included 33,399 patients with synchronous stage IV CRC amongst who 24,784 (74.21 %) and 8615 (25.79 %) patients had colon cancer and rectal cancer, respectively. The median age of diagnosis was 66 years. CEA levels were determined to be normal (N = 3781, 11.32 %), elevated (N = 17,043, 51.03 %) and unknown (N = 12,575, 37.65 %). According to the resection of the primary patients were divided into three groups those who did not undergo resection of their primary (N = 13,444, 40.25 %), had surgery of their primary tumor (N = 19,825, 59.36 %) and unknown status of surgery of the primary tumor (N = 130, 0.39 %).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| N | Percent % | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 33399 | |

| Age | ||

| < 65 years | 15865 | 47.50 |

| > = 65 years | 17534 | 52.50 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 16205 | 48.52 |

| Male | 17194 | 51.48 |

| Grade | ||

| I/II | 17136 | 51.31 |

| III | 8188 | 24.52 |

| Unknown | 8075 | 24.18 |

| Site of primary | ||

| Colon | 24784 | 74.21 |

| Rectum | 8615 | 25.79 |

| Surgery of primary | ||

| No | 13444 | 40.25 |

| Yes | 19825 | 59.36 |

| Unknown | 130 | 0.39 |

| Radiation | ||

| No | 29328 | 87.81 |

| Yes | 3695 | 11.06 |

| Unknown | 376 | 1.13 |

| Lymph node surgery | ||

| No | 14292 | 42.79 |

| Yes | 18574 | 55.61 |

| Unknown | 533 | 1.60 |

| Surgery of non primary regions | ||

| No | 27552 | 82.49 |

| Yes | 5652 | 16.92 |

| Unknown | 195 | 0.58 |

| CEA level | ||

| Normal | 3781 | 11.32 |

| Elevated | 17043 | 51.03 |

| Unknown | 12575 | 37.65 |

| Race | ||

| White/Other | 28624 | 85.70 |

| Black | 4706 | 14.09 |

| Unknown | 69 | 0.21 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 16963 | 50.79 |

| Not married | 15238 | 45.62 |

| Unknown | 1198 | 3.59 |

| Site of metastases | ||

| Other mets | 31552 | 94.47 |

| Distant lymph nodes | 1847 | 5.53 |

Survival Estimates

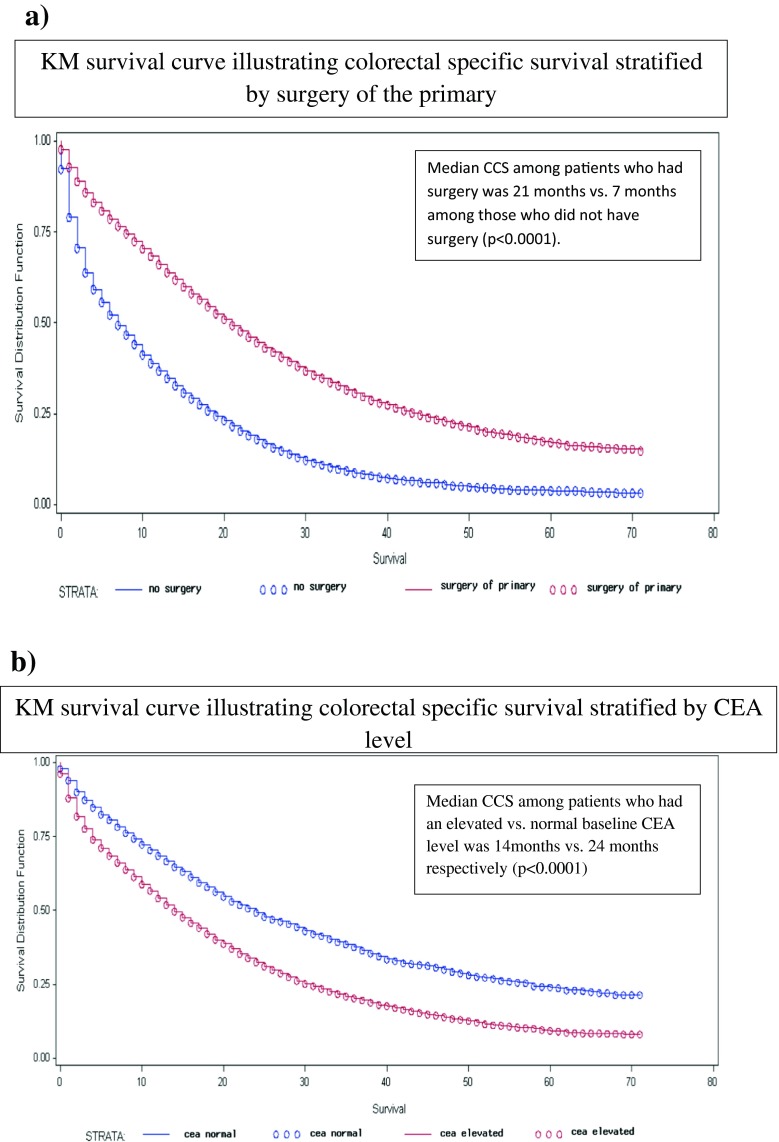

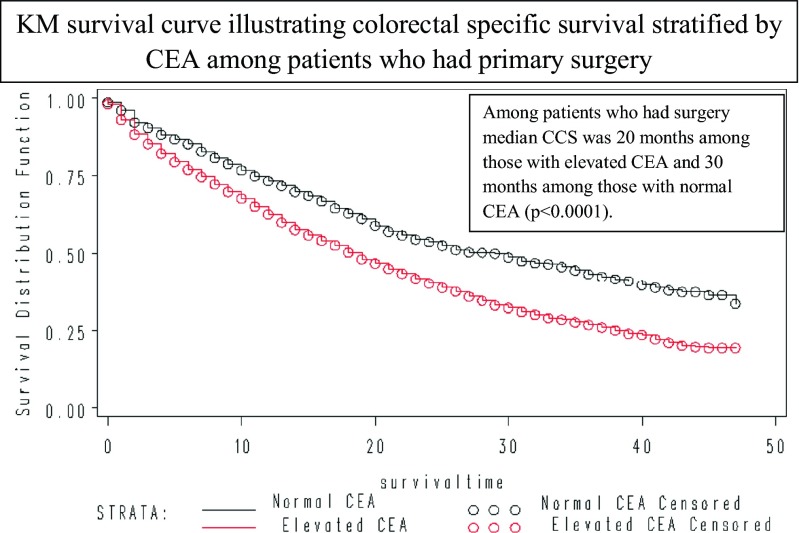

24,067(72.06 %) patients had died of all causes and 20,245(60.62 %) patients had died of colorectal cancer. Table 2 summarizes the 2-year CSS and OS estimates. Median CCS was 15-month. Median CCS was 21- and 7-month among patients who did and did not have surgery of their primary (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1a). Median CCS among patients with a normal versus elevated baseline CEA level was 24- and 14-month respectively (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1b). Among patients who had surgery of their primary, median CCS was 30- and 20-month among those whose baseline CEA was normal and elevated respectively (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). Among patients who had surgery of their primary as well as surgery of sites other than the primary, the median CCS was 37-month among those with a normal baseline CEA level and 24-month among those with an elevated baseline CEA level (p < 0.0001). Five years CCS was 33 % (95 % CI 27–38 %) among patients who had undergone surgery of their primary and surgery of sites other than the primary who had a normal baseline CEA level.

Table 2.

Two years colorectal cancer specific and overall survival among patients with stage IV de novo colorectal cancer

| Colorectal cancer specific survival | Overall survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-year | 95 % Confidence Interval | P-Value | 2-year | 95 % Confidence Interval | P-Value | |

| All | 35 % | 34–35 % | 29 % | 28–30 % | ||

| Age | ||||||

| < 65 years | 45 % | 44–45 % | 40 % | 39–41 % | ||

| > = 65 years | 26 % | 25–26 % | <0.0001 | 19 % | 19–20 % | <0.0001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 33 % | 32–34 % | 28 % | 27–28 % | ||

| Male | 36 % | 35–37 % | <0.0001 | 30 % | 29–31 % | <0.0001 |

| Race | ||||||

| White/Other | 35 % | 34–36 % | 29 % | 28–30 % | ||

| Black | 32 % | 30–34 % | <0.0001 | 26 % | 25–27 % | <0.0001 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Not Married | 30 % | 29–31 % | 23 % | 22–24 % | ||

| Married | 40 % | 39–40 % | <0.0001 | 34 % | 33–35 % | <0.0001 |

| CEA level | ||||||

| Normal | 49 % | 47–51 % | 43 % | 41–45 % | ||

| Elevated | 32 % | 32–33 % | <0.0001 | 27 % | 26–28 % | <0.0001 |

| Grade | ||||||

| I/II | 44 % | 43–45 % | 39 % | 38–40 % | ||

| III | 27 % | 26–28 % | <0.0001 | 23 % | 22–24 % | <0.0001 |

| Site of primary | ||||||

| Colon | 33 % | 32–34 % | 27 % | 26–28 % | ||

| Rectum | 40 % | 39–41 % | <0.0001 | 35 % | 34–35 % | <0.0001 |

| Site of metastases | ||||||

| Distant Lymph nodes | 47 % | 44–50 % | 40 % | 37–43 % | ||

| Other mets | 34 % | 34–35 % | <0.0001 | 29 % | 28–30 % | <0.0001 |

| Surgery of primary | ||||||

| Yes | 45 % | 44–45 % | 40 % | 39–41 % | ||

| No | 18 % | 17–19 % | <0.0001 | 13 % | 12–13 % | <0.0001 |

| Surgery of primary | ||||||

| CEA Normal | 55 % | 53–57 % | 50 % | 47–51 % | ||

| CEA Elevated | 42 % | 40–43 % | <0.0001 | 37 % | 36–38 % | <0.0001 |

| No Surgery of primary | ||||||

| CEA Normal | 28 % | 24–31 % | 20 % | 17–23 % | ||

| CEA Elevated | 17 % | 16–18 % | <0.0001 | 13 % | 12–14 % | <0.0001 |

| Surgery of lymph nodes | ||||||

| Yes | 45 % | 44–46 % | 40 % | 39–41 % | ||

| No | 20 % | 19–21 % | <0.0001 | 14 % | 13–15 % | <0.0001 |

| Radiation | ||||||

| Yes | 42 % | 41–44 % | 38 % | 36–40 % | ||

| No | 34 % | 33–35 % | <0.0001 | 28 % | 27–28 % | <0.0001 |

| Surgery of non primary regions | ||||||

| Yes | 50 % | 48–51 % | 45 % | 43–46 % | ||

| No | 32 % | 31–32 % | <0.0001 | 26 % | 25–26 % | <0.0001 |

Fig. 1.

Colorectal Cancer Specific survival (CCS) among patients with stage IV denovo colorectal cancer stratified by a) Surgery of primary (Yes vs. no) b) Baseline CEA level (Elevated vs. Normal)

Fig. 2.

Colorectal Cancer Specific survival (CCS) among patients with stage IV denovo colorectal cancer stratified by CEA levels among patients who had surgery for primary

Table 3 summarizes the results of the multivariable cox models for the whole cohort. Patients with an elevated CEA had a 56 % increased risk of death from CRC compared to those with a non-elevated CEA (HR = 1.56, 95%CI 1.47–1.65, p < 0.0001). Similarly patients who underwent primary tumor surgery had a 38 % decreased risk of death from CRC compared to those who did not (HR = 0.62, 95 % CI 0.54–0.69, p < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Multivariable model for colorectal cancer specific survival and overall survival of the whole cohort (Adjusted for SEER registry)

| Colorectal cancer specific survival | Overall survival | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | Lower 95 % CI | Upper 95 % CI | P-value | HR | Lower 95 % CI | Upper 95 % CI | P-value | |

| CEA level (elevated vs. normal) | 1.56 | 1.47 | 1.65 | <.0001 | 1.50 | 1.42 | 1.58 | <.0001 |

| Surgery of primary (yes vs. no) | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.69 | <.0001 | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.75 | <.0001 |

| Surgery of non primary (yes vs. no) | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.81 | <.0001 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.81 | <.0001 |

| Race (black vs. white/other) | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.16 | 0.0046 | 1.13 | 1.07 | 1.19 | <.0001 |

| Grade III vs. I/II | 1.76 | 1.68 | 1.83 | <.0001 | 1.73 | 1.66 | 1.80 | <.0001 |

| Site of primary (Colon vs. Rectum) | 1.28 | 1.21 | 1.35 | <.0001 | 1.28 | 1.22 | 1.35 | <.0001 |

| Site of mets (other vs. distant lymph node) | 1.39 | 1.25 | 1.56 | <.0001 | 1.36 | 1.23 | 1.50 | 0.0001 |

| Marital status (yes vs. no) | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.88 | <.0001 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.87 | <.0001 |

| Sex (Male vs. female) | 0.97 | 0.93 | 1.01 | 0.2192 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.03 | 0.6139 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.03 | <.0001 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.03 | <.0001 |

| Lymph node removed (yes vs. no) | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.82 | <.0001 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.73 | <.0001 |

| Radiation (yes vs. no) | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.90 | <.0001 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.89 | <.0001 |

Multivariable models were run stratified by CEA levels (supplementary table). Among patients with an elevated CEA those who underwent surgery of their primary tumor had a 37 % decreased risk of death from CRC compared to those who did not undergo surgery of their primary (HR = 0.63, 95%CI 0.55–0.72, p < 0.0001). Among patients with a normal CEA those who had surgery of their primary had a 46 % decreased risk of death from CRC compared to those who did not undergo surgery of their primary (HR = 0.54, 95 % CI 0.38–0.75, p = 0.0003).

Discussion

In this large population based SEER analysis, we evaluated the prognostic role of baseline CEA and surgical resection of the primary tumor in patients with synchronous stage IV CRC who were diagnosed in an era where biological and modern chemotherapeutic regimens are available. A number of important findings are shown. First, surgery of the primary was associated with a significant impact on overall survival. Second, elevated baseline CEA was associated with worse prognostic outcome. Third, surgical resection of the primary was associated with a survival advantage among patients with either normal or elevated CEA levels with the best prognostic outcome observed among patients who had a normal baseline CEA level and had surgical resection of the primary. Fourth, other factors identified that were associated with a worse prognostic outcome included black race, higher grade of disease, colon as primary site of tumor and older age at diagnosis.

The role of resection of the primary tumor among patients with synchronous stage IV CRC remains an area of controversy with no prospective randomized clinical trial addressing this question. The majority of studies that have been reported to address this issue have been retrospective in nature with data derived from single center experiences [21]. Although well documented that surgical resection of the primary tumor is recommended among symptomatic patients there is no published consensus among those patients with asymptomatic primary tumors and surgically unresectable stage IV disease. One argument for the upfront resection of the asymptomatic primary tumor is to avoid the possible need for emergent surgery documented to occur in up to 20 % of cases [22–24]. Poultsides and colleagues [25] recently reported on 233 patients with synchronous stage IV CRC who received first-line chemotherapy of oxaliplatin or irinotecan-based chemotherapy observing a 7 % reduction in surgical intervention rate needed to palliate primary tumor related events. McCahill and colleagues [26] reported a single arm phase II trial that enrolled 86 patients with colon cancer who had an intact asymptomatic primary tumor and synchronous non-resectable metastatic disease who received oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy with bevacizumab. After a median follow up of 20.7-month, the authors reported a 16.3 % overall rate of major morbidity (surgery or death) associated with the intact primary and a median overall survival of 19.9-month. Evidence from both studies support the notion that routine upfront palliative surgery of asymptomatic primary tumors was not necessary and that biologic agents such as bevacizumab could safely be used among patients with intact primary tumors without substantial risk of perforation.

The question that now arises is whether resection of the asymptomatic primary has an impact on survival in a surgically unresectable patient. In a retrospective analysis of patients with stage IV CRC enrolled in the phase III CAIRO and CAIRO2 studies, Venderbosch and colleagues [27] reported a statistically significant improvement in the median overall survival of 5.3- and 7.3-month in each of the two studies respectively favoring the group that had undergone resection of the primary prior to randomization into the clinical trials. In a recent pooled analysis of 810 patients (with synchronous stage IV disease) evaluated in four first-line chemotherapy trials (FFCD 9601, FFCD 2000–05, ACCORD, ML16987) Faron and colleagues [28] reported that after adjustment for primary tumor location, CEA level, ALP level, WBC level, performance status and number of metastatic sites, resection of the primary was associated with a 37 % reduction in the risk of death compared to patients who did not undergo resection of the primary tumor (HR = 0.63, 95%CI 0.53–0.75, p < 0.0001). The authors also noted that certain subgroups such as those with extremely elevated CEA or LDH did not appear to derive as much benefit which may be due to high degree of tumor burden. The results of these studies appear to provide additional support for the results of our present study where we demonstrate a 33 % decreased risk of death from CRC among patients who undergo resection of their primary tumor (HR = 0.61, 95%CI 0.54–0.69, p < 0.0001) introducing the hypothesis that perhaps there is an additional role of survival benefit associated with primary tumor resection beyond palliative surgical intervention only to treat or abate symptoms.

The survival benefit of resection of low volume distant metastatic disease has been demonstrated in several studies with 5-year survival rates ranging from 30 to 50 % following hepatic resection and 25 to 35 % following resection of lung metastases [29–36]. Evidence generated from retrospective and prospective studies have demonstrated a survival benefit from resection of the primary and low volume hepatic (or lung) metastases either upfront when the metastatic lesions are resectable or following neoadjuvant chemotherapy when the metastatic lesions are converted from unresectable to resectable [34–42]. In a recent retrospective study of a single institutional experience in Singapore, Chew and colleagues [42] reported 5-year CCS survival rates of 34.5 % when the primary and all metastatic lesions were resected compared to 3.3 % when only a palliative resection of the primary was performed (p < 0.001). In our present study we observed a 5-year CCS survival of 23 % among patients who had undergone surgery of their primary and surgery of sites other than the primary. However due to the limitation of the SEER registry, whether all sites or just selected sites of metastatic disease were surgically resected or ablated in each patient is unknown.

Baseline CEA has been shown to be prognostic factor among patients with CRC [14–17]. Using data derived from two prospective randomized trials from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP), Wolmark and colleagues [16] showed that an elevated preoperative baseline CEA level may function as a poor prognostic factor that was independent of both stage and the number of positive lymph nodes within the surgical specimen. Using data from SEER, Thirunavukarasu and colleagues [17] demonstrated that among patients with colon cancer diagnosed in 2004 elevated pre-treatment CEA level was independently associated with a 60 % increased risk of death compared to patients with a normal pre-treatment CEA level. Hsu and colleagues [41] retrospectively looked at 422 patients with synchronous stage IV CRC identifying several factors that influenced survival including baseline CEA level and treatment of liver metastases. Our results provide additional support in that CEA level is an independent prognostic factor among patients with synchronous stage IV CRC. Interestingly we found that regardless of baseline CEA level, surgery of the primary tumor was associated with a decreased risk of death from CRC of 37 and 46 % among those with an elevated and normal CEA level respectively.

We acknowledge that our study has a number of important limitations that need to be taken into account when interpreting the results. Information on potential confounding variables such as associated co-morbid conditions, metastatic disease burden status, performance status and presence or absence of symptoms that can influence the decision to resect the primary are not recorded within the SEER database. Furthermore, we understand that each patient must be analyzed on a case by case basis for considering or deferring resection of the primary tumor given a multitude of factors including the possibility of delaying the use of systemic chemotherapy which may be of high priority in a patient with unresectable disease and a high degree of tumor burden. It may be that the survival advantage experienced secondary to surgical resection of the primary tumor is restricted to the group of patients with a better performance status and the least distant disease burden; factors which have been shown to influence survival outcome [41]. Furthermore with the use of the SEER registry, information on the type of chemotherapy was also unavailable. However the cohort studied were patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2009. It is assumed that most of these patients would have access to a modern chemotherapy regimen of irinotecan or oxaliplatin based therapy given their FDA approval in 2002. Furthermore both bevacizumab and cetuximab were approved by the FDA in February 2004 and we would assume that eligible candidates would have received some sort of biological therapy in addition to chemotherapy affording maximum survival advantage.

In conclusion, our study results supports the hypothesis that resection of the primary tumor among patients with synchronous stage IV CRC is associated with a potential survival advantage. Several questions still remain including the necessity of surgery, whether the survival advantage afforded by surgery adds to that afforded by state of the art chemotherapy and biological therapy, and whether surgery of the intact asymptomatic primary truly benefits all groups of patients or a specific subgroup. Perhaps one way of identifying a good prognostic group is by including baseline CEA level as a prognostic factor. Regardless it is interesting to note that even in the era of biological and advanced chemotherapeutic regimens more than half of patients who presented with synchronous stage IV CRC in this era underwent surgery of their primary. Currently, two ongoing clinical trials (CAIRO4 and SYNCHRONOUS TRIAL) are looking at the role of surgical resection of the asymptomatic primary. Until results of such trials become available the question of whether or not to surgically resect the primary tumor should be made on a case by case basis taking into account factors such as presence of associated symptoms and whether distant metastatic lesions can be resected.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steingberg SM, Barkin JS, Kaplan RS, Stablein DM. Prognostic indicators of colon tumors: the gastrointestinal tumor study group experience. Cancer. 1986;57:1866–1870. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860501)57:9<1866::AID-CNCR2820570928>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3677–3683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grothey A, Sargent D, Goldberg RM, Schmoll HJ. Survival of patients with advanced colorectal cancer improves with the availability of fluorouracil-leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in the course of treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(7):1209–1214. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanoff HK, Sargent DJ, Campbell ME, et al. Five year data and prognostic factor analysis of oxaliplatin and irinotecan combinations for advanced colorectal cancer: N9741. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(35):5721–5727. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun YS, Vauthey JN, Boonsirikamchai P, et al. Association of computed tomography morphologic criteria with pathologic response and survival in patients treated with bevacizumab for colorectal liver metastases. JAMA. 2009;302(21):2338–2344. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruo L, Gougoutas C, Paty PB, Guillem JG, Cohen AM, Wong WD. Elective bowel resection for incurable stage IV colorectal cancer: prognostic variables for asymptomatic patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196(5):722–728. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook AD, Single R, McCahill LE. Surgical resection of primary tumors in patients who present with stage IV colorectal cancer: an analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data, 1988 to 2000. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(8):637–645. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenberger A, Whelan RL, Neugut AI. Survival and symptomatic benefit from palliative primary tumor resection in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23(6):559–568. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0456-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scoggins CR, Meszoely IM, Blanke CD, Beauchamp RD, Leach SD. Nonoperative management of primary colorectal cancer in patients with stage IV disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6(7):651–657. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0651-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans MD, Escofet X, Karandikar SS, Stamatakis JD. Outcomes of resection and non-resection strategies in management of patients with advanced colorectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stelzner S, Hellmich G, Koch R, Ludwig K. Factors predicting survival in stage IV colorectal carcinoma patients after palliative treatment: a multivariate analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89(4):211–217. doi: 10.1002/jso.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin R, Paty P, Fong Y, et al. Simultaneous liver and colorectal resections are safe for synchronous colorectal liver metastatsis. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:233–242. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00390-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wanebo HJ, Rao B, Pinsky CM, Hoffman RG, Stearns M, Schwartz MK, Oettgen HF. Preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level as a prognostic indicator in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:448–451. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197808312990904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moertel CG, O’Fallon JR, Go VL, O’Connell MJ, Thynne GS. The preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen test in the diagnosis, staging, and prognosis of colorectal cancer. Cancer. 1986;58(3):603–610. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860801)58:3<603::AID-CNCR2820580302>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolmark N, Fisher B, Wieand HS, et al. The prognostic significance of preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen levels in colorectal cancer. Results from NSABP (National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project) clin- ical trials. Ann Surg. 1984;199(4):375–382. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198404000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thirunavukarasu P, Sukumar S, Sathaiah M, et al. C-stage in colon cancer: implications of carcinoembryonic antigen biomarker in staging, prognosis, and management. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(8):689–697. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zamcheck N. The present status of CEA in diagnosis, prognosis, and evaluation of therapy. Cancer. 1975;36:2460–2468. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197512)36:6<2460::AID-CNCR2820360631>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steele G, Jr, Ellenberg S, Ramming K, et al. CEA monitoring among patients in multi-institutional adjuvant G.I. therapy protocols. Ann Surg. 1982;196:162–169. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198208000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu JB, Gross CP, Wilson LD, et al. NCI SEER public-use data: applications and limitation in oncology research. Oncology (Williston Park) 2009;23(3):288–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verhoef C, de Wilt JH, Burger JW, Verheul HM, Koopman M. Surgery of the primary in stage IV colorectal cancer with unresectable metastases. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(Suppl 3):S61–S66. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(11)70148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tebbutt NC, Norman AR, Cunningham D, et al. Intestinal complications after chemotherapy for patients with unresected primary colorectal cancer and synchronous metastases. Gut. 2003;52(4):568–573. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.4.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michel P, Roque I, Di Fiore F, Langlois S, Scotte M, Tenière P, Paillot B. Colorectal cancer with non-resectable synchronous metastases: should the primary tumor be resected? Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28(5):434–437. doi: 10.1016/S0399-8320(04)94952-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarela AI, Guthrie JA, Seymour MT, Ride E, Guillou PJ, O’Riordain DS. Non-operative management of the primary tumour in patients with incurable stage IV colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88(10):1352–1356. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poultsides GA, Servais EL, Saltz LB, et al. Outcome of primary tumor in patients with synchronous stage IV colorectal cancer receiving combination chemotherapy without surgery as initial treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(20):3379–3384. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCahill LE, Yothers G, Sharif S, et al. Primary mFOLFOX6 plus bevaci- zumab without resection of the primary tumor for patients presenting with surgically unresectable metastatic colon cancer and an intact asymptomatic colon cancer: definitive analysis of NSABP trial C-10. J Clin Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venderbosch S, de Wilt JH, Teerenstra S, et al. Prognostic value of resection of primary tumor in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer: retrospective analysis of two randomized studies and a review of the literature. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(12):3252–3260. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1951-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthieu Faron, Abderrahmane Bourredjem, Jean-Pierre Pignon et al. Impact on survival of primary tumor resection in patients with colorectal cancer and unresectable metastasis: Pooled analysis of individual patients’ data from four randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 30, 2012 (suppl; abstr 3507)

- 29.Wong SL, Mangu PB, Choti MA, et al. Clinical evidence review on radiofrequency ablation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:493–508. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pozzo C, Basso M, Cassano A, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment of unresectable liver disease with irinotecan and 5-fluorouracil plus folinic acid in colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(6):933–939. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pawlik TM, Schulick RD, Choti MA. Expanding criteria for resectability of colorectal liver metastases. Oncologist. 2008;13(1):51–64. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Jong MC, Pulitano C, Ribero D, et al. Rates and patterns of recurrence following curative intent surgery for colorectal liver metastasis: an international multi-institutional analysis of 1669 patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250(3):440–448. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b4539b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adam R, Avisar E, Ariche A, et al. Five year survival following hepatic resection after neoadjuvant therapy for nonresectable colorectal. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8(4):347–353. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onaitis MW, Petersen RP, Haney JC, et al. Prognostic factors for recurrence after pulmonary resection of colorectal cancer metastases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(6):1684–1688. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andres A, Mentha G, Adam R, et al. Surgical management of patients with colorectal cancer and simultaneous liver and lung metastases. Br J Surg. 2015 doi: 10.1002/bjs.9783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choti MA, Sitzmann JV, Tiburi MF, et al. Trends in long-term survival following liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2002;235(6):759–766. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200206000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai MS, Su YH, Ho MC, Liang JT, Chen TP, Lai HS, Lee PH. Clinicopathological features and prognosis in resectable synchronous and metachronous colorectal liver metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(2):786–794. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fong Y, Salo J. Surgical therapy of hepatic colorectal metastasis. Semin Oncol. 1999;26:514–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fong Y, Cohen AM, Fortner JG, et al. Liver resection for colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:938–946. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nordlinger B, Sorbye H, Glimelius B, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with FOLFOX4 and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC Intergroup trial 40983): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60455-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muratore A, Zorzi D, Bouzari H, et al. Asymptomatic colorectal cancer with un-resectable liver metastases: immediate colorectal resection or up-front systemic chemotherapy? Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:766–770. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chew MH, Teo JY, Kabir T, Koh PK, Eu KW, Tang CL. Stage IV colorectal cancers: an analysis of factors predicting outcome and survival in 728 cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16(3):603–612. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1725-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]