Abstract

Hepatocytes, the major parenchymal cells in the liver, play pivotal roles in metabolism, detoxification, and protein synthesis. Hepatocytes also activate innate immunity against invading microorganisms by secreting innate immunity proteins. These proteins include bactericidal proteins that directly kill bacteria, opsonins that assist in the phagocytosis of foreign bacteria, iron-sequestering proteins that block iron uptake by bacteria, several soluble factors that regulate lipopolysaccharide signaling, and the coagulation factor fibrinogen that activates innate immunity. In this review, we summarize the wide variety of innate immunity proteins produced by hepatocytes and discuss liver-enriched transcription factors (e.g. hepatocyte nuclear factors and CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins), pro-inflammatory mediators (e.g. interleukin (IL)-6, IL-22, IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α), and downstream signaling pathways (e.g. signal transducer and activator of transcription factor 3 and nuclear factor-κB) that regulate the expression of these innate immunity proteins. We also briefly discuss the dysregulation of these innate immunity proteins in chronic liver disease, which may contribute to an increased susceptibility to bacterial infection in patients with cirrhosis.

Keywords: Liver, acute phase protein, cytokine, infection, transcription factor

The liver is the largest gland in the body, and 70–85% of the liver volume is occupied by parenchymal hepatocytes. Hepatocytes robustly express and release large amount of proteins to the blood. Therefore, it is possible that the hepatocyte immune function is to secrete specific proteins into blood. For example, hepatocytes constitutively produce and secrete a variety of proteins that play important roles in innate immunity (Table 1).1 Most of these proteins are further elevated after bacterial infection. Additionally, hepatocytes receive pathogenic and inflammatory signals and respond by secreting innate immunity proteins to the bloodstream (Table 1). As many of these proteins are rapidly produced after stimulation, they are grouped as acute-phase proteins (APPs). Hundreds of APPs have been identified, exhibiting a wide variety of functions including the activation of innate immunity. These proteins either directly kill pathogens or orchestrate the immune system for efficient pathogen clearance. This mechanism is an ancient immune approach that has been maintained and developed through evolution. Many inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-22, IL-1β, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), regulate APP production via the activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription factor 3 (STAT3) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). IL-6 expression is immediately induced by pathogens in immune cells and epithelial cells,2,3 including hepatocytes.4 IL-1β is mainly released by innate immune cells upon stimulation by pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecules and damage-associated molecular pattern molecules, depending on the generation of the inflammasome.5,6 Hepatocytes respond to stimulation by IL-6, IL-1β, and other cytokines in the serum and produce large amount of APPs, which kill bacteria and regulate the immune response.7 Because IL-6, IL-1β, and many other inflammatory cytokines that stimulate the immune functions of hepatocytes are mainly produced by the immune cells, hepatocytes can be considered as important downstream effector cells actively participating in the host immune system. Here, we summarize the hepatocyte-derived innate immunity proteins that directly promote pathogen clearance and immune regulation. We also summarize a variety of cytokines and their downstream signals that induce the expression of innate immunity proteins in hepatocytes as well as liver-enriched transcription factors that control the constitutive and inducible expression of innate immunity proteins in hepatocytes.

Table 1. Biosynthesis of secreted innate immunity proteins by hepatocytes.

| Innate Immunity proteins | Mainly synthesized in hepatocytes | Function | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | C1r/s, C2, C4, C4bp | Activate C classical pathway | 13,14 | |

| Alternative | C3, B | Activate C alternative pathway | 13,14,15 | |

| Cs | Lectin | MBL, MASP1, 2 3, MAp19 | Activate C MBL pathway | 16,17,18 |

| Terminal | C5, C6, C8, C9 | Terminal C components | 13,14 | |

| Regulators | I, H, C1-INH | Inhibit C activation | 13 | |

| Opsonins | Pentraxins | CRP, SAP | Bind to microbes and subsequently activate Cs and phagocytosis to kill microbes | 19,20,21,35 |

| SAA | SAA | Binds to the outer membrane protein A family members on bacteria to activate phagocytosis | 24,25 | |

| LPS signaling regulators | Lipid transferase | LBP | Binds to LPS and subsequently transfers LPS to a receptor complex (TLR4/MD-2) via a CD14-enhanced mechanism | 51,52,53 |

| sCD14 | Soluble CD14 | Stimulates or inhibits LPS signaling depending on its concentration and environment | 54,55,56,57 | |

| sMD-2 | Soluble MD-2 | Stimulates or inhibits LPS signaling depending on its concentration and environment | 58,59 | |

| Iron metabolism | Iron-carrying protein | Transferrin | Binds to free iron, limiting iron availability to pathogens | 86 |

| -related proteins | Lipocalin-2 | Lipocalin-2 | Attenuates iron uptake by bacteria via binding to siderophores | 94,95,96,97 |

| Anti-microbial peptide | Hepcidin (also LEAP) | Anti-microbial peptide via limiting iron availability | 108,109 | |

| Hemopexin | Hemopexin | Retains heme from the bacteria by binding to heme | 103 | |

| Others | Clotting factors | Fibrinogen | A central regulator of the inflammatory response | 111 |

| PGRPs | PGLYP2 | Anti-inflammatory response via digestion of peptidoglycan on the bacterial wall | 160,161 | |

| Proteinase inhibitors | AAT, ACT, α1-CPI, α2M | Inactivate proteases released by pathogens and dead or dying cells | 124,125,126 | |

α1-CPI, α1-cysteine proteinase inhibitor (thiostain); α2M, α2-macroglobulin; AAT, antitrypsin; ACT, antichymotrypsin; B, factor B; C1-INH, C1 inhibitor; CRP, C-reactive protein; Cs, complements;, I, factor I; H, factor H; LBP, LPS-binding protein; LEAP, liver expressed antimicrobial peptide; MBL, mannan-binding lectin; MASP, mannan-binding lectin-associated serine proteases; PGRPs, peptidoglycan-recognition proteins; PGLYP2, peptidoglycan-recognition protein-2; SAA, serum amyloid A; SAP, serum amyloid P.

Hepatocyte-derived innate immunity proteins

Complement proteins

The first approach of hepatocytes to defeat infection is to directly kill pathogens, especially bacteria, by secreting bactericidal complement proteins, which are a valuable component of humeral immunity. Complement proteins belong to the innate immune system. Complements form chemical cascades to create pores in the membranes of invading bacteria or pathogenic host cells and lyse the targets. Three pathways activate the complement system: the classical pathway, the alternative pathway, and the lectin pathway.8 Immune cells also receive complement signals to modify their activity.

Hepatocytes constitutively produce most of the proteins in the complement system and maintain their sufficiently high serum concentrations, eliminating pathogens, and fine-tuning the immune system.1,9,10 These complement proteins are further elevated after inflammatory stimulation. For example, hepatocytes are mainly responsible for the production of the most abundant complement C3 in the blood (130 mg/dl).11 These high basal levels of serum C3 are further increased by 50% during the acute phase.12 In addition, hepatocytes produce other plasma complement components and their soluble regulators, including the classical (C1r/s, C2, C4, C4bp),13,14 alternative (C3, factor B),13,14,15 lectin (mannose-binding lectin (MBL), mannan-binding lectin-associated serine proteases (MASP1-3), MAp19),16,17,18 and terminal (C5, C6, C8, C9)13,14 pathways of the complement system as well as soluble regulators (factors I, H, and C1 inhibitor)13 (Table1). Immune cells and endothelial cells also produce these proteins, but their contributions to plasma levels are insignificant compared with hepatocytes. The transcription of these complement genes is controlled by liver-enriched transcription factors (e.g. hepatocyte nuclear factors (HNFs), CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs)), cytokine-activated signals (e.g. NF-κB, STAT3), and other transcription factors (e.g. AP-1, estrogen and glucocorticoid receptors).12

Other opsonins besides complements: C-reactive protein, serum amyloid a proteins, and serum amyloid p component

Opsonin proteins assist in the phagocytosis of foreign pathogens or complement activation. Because of the pro-phagocytic activity, many complement proteins are also considered opsonins. In addition, several APPs, including C-reactive protein (CRP), serum amyloid a proteins (SAA), serum amyloid p component (SAP), which are mainly produced by hepatocytes, are also strong opsonins. Other than opsonic activity, these three proteins also profoundly regulate immune system function.

CRP belongs to the pentraxin family and contains five repeats of a single protomer. In healthy individuals, serum CRP levels are low (typically <1mg/dl). Upon stress challenge, including bacterial infection and tissue injury, hepatocytes rapidly synthesize and secrete a large amount of CRP into the blood, reaching levels 1000 times higher than basal levels.19 This effect is executed by IL-6 and enhanced by IL-1β. Downstream signals, including STAT3, C/EBPs, and NF-κB, are responsible for the increased transcription.19,20,21CRP is a strong opsonin that adheres to phosphatidylcholine on the outer membranes of bacteria, fungi, and parasites and subsequently alters host cells. CRP also adheres to H1 histones, snRNPs, phosphoethanolamine, and laminin. Upon CRP ligation, two major downstream effects occur. First, CRP triggers the classical complement pathway through binding and activating C1q. CRP facilitates the cascade through C3 convertase and allows the downstream cascades to complete the killing function.19,20,21,22 In this way, CRP provides a more rapid and efficient way to execute the complement classical pathway. By contrast, the binding of CRP to bacteria inhibits the alternative pathway of complement activation. CRP recruits factor H for its function, whereas factor H prevents C3b binding to the membrane in the alternative complement activation cascade. Second, as an opsonin, CRP provides a recognition site for phagocytes to identify targets. The ligation of CRP to bacteria or apoptotic cells directs the efferocytosis of both macrophages and neutrophils for their clearance from the body. Recognition of CRP by Kupffer cells/macrophages and neutrophils is mediated by binding to the receptors FcγRI and FcγRII expressed on these cells.19,20,21,22

CRP possesses both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties. CRP increases adhesion molecules in endothelial cells to allow the infiltration of inflammatory cells to the tissue.19,20,21,22 Additionally, CRP increases the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, and TNF-α. By contrast, by binding to the H1-containing nuclear components, CRP facilitates the masking and phagocytosis of these autoantigens to prevent auto-sensitization. CRP can also induce neutrophils to shed their IL-6 receptor and L-selectin from the membrane. In this way, CRP desensitizes the IL-6 signal and reduces neutrophil infiltration to inflamed tissues. Also, CRP increases the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-10 and IL-1R, and reduces the superoxide production and chemotaxis of neutrophils. The exact pro- or anti-inflammatory function of CRP might depend on the situation of the local area.19,20,21 Finally, serum levels of high-sensitivity CRP are markedly elevated in patients with alcoholic hepatitis and positively correlate with mortality in these patients.23 However, whether CRP inhibits or promotes systemic inflammatory response syndrome in patients with alcoholic hepatitis remains obscure.

SAA is a group of four genes with multiple functions from lipid metabolism to immunity in humans. SAA1 and SAA2 are acute response genes that are collectively called A-SAA. In acute inflammation and infection, the serum level of SAA can increase more than 1000 times over the basal level.24,25 This response is largely dependent on IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, which activate downstream signals including STAT3, NF-κB, and C/EBPs. Although A-SAA is also expressed in other tissues, the dominant cell responsible for its production is the hepatocyte.24,25 SAA3 is a pseudogene in human. SAA4 is constitutively expressed in adipose tissue and accounts for basal serum SAA levels.24,25

SAA is an opsonin specific to Gram-negative bacteria by directly binding to the outer membrane protein A family members on these bacteria. By contrast, SAA has no opsonin activity against Gram-positive bacteria. Upon binding to Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, SAA facilitates their phagocytosis by neutrophils and macrophages. Moreover, SAA also enhances the immune activity of phagocytes. In the presence of SAA, neutrophils show increased respiratory bursts, and macrophages produce high amounts of IL-6 and TNF-α.26 SAA also activates the innate immune system independent of its opsonic activity as a pro-inflammatory factor. To date, a specific receptor for SAA has not been found. SAA is thought to react with several important inflammation-related receptors to exert its function, including Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), TLR4, formyl peptide receptor-like 1, receptor for advanced glycation end products, and CD36, followed by the activation of NF-κB, mitogen-activated protein kinase associated protein 1, and IRFs and the upregulation of inflammation-related genes.24 Although it might have anti-inflammatory functions under certain conditions,27,28 SAA generally acts as a pro-inflammatory mediator. Specifically, upon stimulation with SAA, human neutrophils produce IL-8 to recruit additional neutrophils to the inflammatory site.29 Furthermore, SAA upregulates granulocyte-colony stimulating factor expression on macrophages and subsequently supports local neutrophil infiltration and function.30 Moreover, SAA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome for the production of IL-1β from macrophages31 and stimulates macrophages to express CCL232, CCL2033, and TNF-α28 to promote local inflammation.

Similar to CRP, SAP is also a member of the pentraxin family with high basal levels (approximately 3–5 mg/dl) in blood from normal healthy people.34 Upon infection, SAP is rapidly upregulated in the liver (hepatocytes) via the activation of STAT3 and C/EBPβ.35 As a well-known opsonin, SAP facilitates the clearance of many pathogens. For example, SAP facilitates C3b deposition to Streptococcus pneumonia and the activation of the classical complement pathway, thereby directly killing bacteria and also increasing phagocytosis.34 SAP interacts with MBL to enhance the binding of C3 and C4 to Candida albicans as well as the downstream phagocytosis by neutrophils.36

FcγRI and FcγRIII are the SAP receptors in mice. By binding to these receptors, SAP activates neutrophils and macrophages and subsequently engulfs target pathogens.37,38 SAP also binds to H1 histone and then solubilizes chromatin. Because H1 histone is found on the membrane of apoptotic bodies and necrotic particles, SAP binding produces an opsonizing effect on the apoptotic bodies of neutrophils and lymphocytes, facilitating their ingestion by macrophages. This process is critical to eliminate nuclear antigens and prevent autoimmunity as in systemic lupus erythematosus.39,40,41 SAP also inhibits the uptake of macrophages on Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the intracellular bacterial growth. In this manner, SAP suppresses the pathogenic progress of tuberculosis.42,43 However, many studies have also reported the suppressive role of SAP in pathogen clearance. SAP prevents classic complement activation by LPS in several strains of Gram-negative bacteria, including Salmonella enteric, Salmonella entericaserovar, Copenhagen Re, E. coli J5, and Haemophilus influenza, thereby inhibiting the clearance of these pathogens and devastating the infection.44,45 Thus, the exact function of SAP might depend on the features of the specific pathogen.

As a potent APP, SAP also directly regulates the function of the innate immune system. In contrast to SAA, SAP's effect on the innate immune system is overall inhibitory. SAP binds to FCγRII and reduces the adhesion of neutrophils to fibronectin.46 SAP inhibits the M2 phenotype polarization of alveolar macrophages, increases CXCL10 expression, and ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis.47,48 Despite the discrepancy in the regulation of IL-10 expression, in a model of renal fibrosis, SAP inhibits the inflammatory polarization of macrophages and promotes the alternative polarization of macrophages, likely the M2a phenotype.49,50

LPS-binding protein, soluble CD14, and soluble MD-2

LPS is a membrane component of Gram-negative bacteria. As an important pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecule, LPS is sensed by TLR4. TLR4 is widely expressed in the immune system and epithelial cells. TLR4 activation by LPS triggers strong NF-κB activation and downstream inflammatory responses. Interestingly, TLR4 does not directly interact with LPS. LPS must be handled stepwise by LPS-binding protein (LBP), CD14, and MD-2 to form a TLR4-MD-2-LPS complex for downstream signaling. Interestingly, hepatocytes are the major source of LBP,51,52,53soluble CD14 (sCD14),54,55,56,57 and soluble MD-2 (sMD-2),58,59 playing a key role in regulating LPS signaling.

Normal hepatocytes express LBP at low levels, but levels are elevated after stimulation with IL-6, IL-22, IL-1β, and TNF-α, which are controlled by C/EBPβ, AP-1, and STAT3.51,52,53CD14 is highly expressed on the surface of monocytes/macrophages and strongly upregulated during the differentiation of monocytic precursor cells into mature monocytes, whereas hepatocytes are the major source of sCD14. Expression of sCD14 in hepatocytes is induced after treatment with IL-6, IL-1, and TNF-α, and its transcription is controlled by AP-1, C/EBPs, and STAT3.54,55,56,57 In addition, sMD-2 is also produced by hepatocytes and induced by IL-6. Transcription of sMD-2 is regulated by STAT3, C/EBPβ, and PU.1.58,59

LBP is a 60-kDa glycoprotein that is predominantly synthesized by hepatocytes. As an APP, its production is upregulated after infection and largely dependent on IL-1β and IL-6.60 By recognizing the lipid A component of LPS, LBP can be considered the first step of LPS detection and reaction by the host. LBP binds to the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, where LPS resides. This binding depends on both calcium and albumin. Upon efficient binding, LBP assembles LPS to both soluble and membrane-bound CD14, activating the LPS signal. Without LBP, the sensitivity of LPS and Gram-negative bacteria diminishes up to 1000 times.61 In Gram-negative bacteria infection models, including Klebsiella pneumonia,62 Salmonella typhimurium,63,64 and E. coli65 infection, LBP deficiency led to high mortality and reduced immune response, especially the recruitment of neutrophils and the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-6, MIP-2, and TNF-α. Accordantly, blocking LBP protected mice from LPS-induced septic shock by diminishing LPS signaling.66 By contrast, very high concentrations of LBP inhibit the LPS signal, displaying a modulatory function that protects the host from septic shock in severe infection.67 High LBP concentrations detoxify LPS by binding it to chylomicrons as a local mechanism to protect the intestinal cells.68

LBP also binds to pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecules on Gram-positive bacteria to modify the reactivity of the host immune system. However, the exact function of LBP in the control of immunity is controversial. Several studies have suggested that LBP boosts the clearance of Gram-positive bacteria. For example, Weber et al.69 reported that Gram-positive pneumococci cell walls depend on LBP to stimulate TLR2 for the production of TNF-α. LBP directly binds to live bacteria or the extracted cell wall component. This finding supported the positive involvement of LBP in the Gram-positive bacteria signaling reaction of the immune system. Subsequent studies have revealed that LBP binds to both diacetylated and triacetylated lipoproteins, the natural ligands of TLR1 and TLR2, and links them to CD14. This process activates TLR2 on human mononuclear cells.70 LBP also facilitates the recognition of lipoteichoic acid (LTA), the major immunogenic molecule of Staphylococcus aureus for the activation of TLR2. LBP transfers LTA to CD14 and activates TLR2.71 By contrast, other studies have noted that LBP impedes the immune function against Gram-positive bacteria. Although LBP-deficient mice were susceptible to Gram-negative K. pneumonia infection, they did not differ from wild type (WT) mice when challenged with S. pneumonia. LBP expression was greatly increased in K. pneumonia infection but only marginally increased in S. pneumonia,72 which may explain why LBP controls K. pneumonia infection but not S. pneumonia infection. In addition, LBP may also act an anti-inflammatory mediator by inhibiting LTA signaling. LTA is highly capable of activating the immune reaction without LBP. LBP inhibits the LTA-mediated activation of both endothelial cells and macrophages and attenuates the LTA-induced release of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α.73,74 LBP also binds and detoxifies LTA via chylomicrons.68 Collectively, LBP likely plays diverse roles in the control of innate immunity dependent on the LBP concentrations and the bacterial structure.

After binding to LBP, the LPS signal is transferred to CD14. CD14 is typically a membrane protein ready to accept LPS from LBP. However, many cell types do not express CD14 and require sCD14 to accomplish the LPS signal. For example, platelets do not express CD14 and partially rely on sCD14 in the plasma to respond to LPS and shed sCD40L.75 sCD14 is mainly produced by hepatocytes, and this expression is increased by IL-6 stimulation.55,56 sCD14 can compensate for the loss of membrane CD14 on monocytes for the response to LPS, indicating a similar function for sCD14 and mCD14 in activating TLR4.76 As with LBP, sCD14 has opposite biological functions according to its concentration. sCD14 at physiological concentrations potentiates the LPS signal by forming a TLR4 complex and mediating the activation of the receptor.77 Binding to LPS by sCD14 itself inhibits Gram-negative bacteria.78 However, very high concentrations of sCD14, as observed in sepsis patients, attenuate LPS-induced monocyte activation. In this setting, sCD14 competes with membrane CD14 to bind to the LPS–LBP complex. Moreover, sCD14 bound to LPS can be further transported to lipoproteins, diminishing the bioactivity of LPS before depletion by hepatocytes. This process could protect the body from overactive inflammatory responses to severe infections.79 Human sCD14 transgene in mice prevent LPS-induced lethality by limiting the amount of LPS binding to monocytes.80 Like LBP, sCD14 can drive the formation of the TLR1/2 tertiary complex for triacetylated bacterial lipoprotein signaling, likely also contributing to the immune reaction against Gram-positive bacteria.81 In summary, LBP and sCD14 play both stimulatory and inhibitory roles in controlling LPS signaling depending on their concentrations and environments. These dual roles not only protect the infected host from infection by promoting inflammation in local sites but may also attenuate potentially detrimental systemic responses to LPS.

The last step in forming the LPS-CD14-MD-2-TLR4 receptor complex is the integration of MD-2. Other than membrane-bound MD-2, sMD-2 was also identified and categorized as an APP. sMD-2 is mainly produced by hepatocytes and is significantly induced by IL-6 but not IL-1β.58,59 Both membrane-bound MD-2 and sMD-2 can help activate TLR4 for downstream immune function. Moreover, sMD-2 also acts as an opsonin to promote neutrophils to eliminate Gram-negative bacteria58 or inhibit the growth of Gram-positive bacteria by binding to peptidoglycan.78

In summary, responding to LPS is a critical step in initiating the immune reaction against invading Gram-negative bacteria. Hepatocytes secrete LBP, sCD14, and sMD-2 to accomplish the TLR4 signal. In addition, sMD-2 also directly inhibits bacterial growth and acts as opsonins to promote bacterial clearance.

Iron metabolism-related proteins: transferrin, lipocalin-2, hemopexin, and hepcidin

Iron is a unique trace element in organisms. In mammals, iron is a component of hemoglobin, a necessary oxygen carrier in red blood cells and plays a variety of important functions. First, iron actively participates in fundamental redox reactions due to its feature in changing the covalence. Second, iron is an element of many energy-producing reactions, including cytochromes a, b, and c; nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydride; and succinate dehydrogenases. As a coenzyme of catalase, iron helps break down peroxides to harmless oxygen.82 Third, iron is necessary for many immune cells. Myeloperoxidase, an enzyme abundant in the primary granules of neutrophils, requires iron for ROS production and bactericidal properties. Thus, iron deficiency would result in the dysfunction of neutrophils and susceptibility to infections.82 Finally, iron is involved in NK cell and T cell proliferation as well as pro-inflammatory Th1 cell differentiation.83

Apart from the necessary functions of iron, it may also cause oxidative damage in an unbound state. Humans evolved an entire molecular system to sequester iron from microorganisms and regulate the blood iron concentration. Transferrin, lactoferrin and ferritin are the dominant chaperones binding to free iron. Hemoglobin and heme bind to hepatoglobin and hemopexin, respectively. Upon binding to these proteins, iron and heme are maintained safely and delivered between host cells. The blood iron concentration is also tightly regulated by hepcidin. Therefore, most microorganisms cannot acquire iron to proliferate efficiently.84 However, pathogenic bacteria evolved three ways to obtain iron from the host: (i) releasing siderophores that compete with the iron chaperones in the host and chelate iron for the use of bacteria; (ii) actively uptake and use iron from heme; and (iii) express transferrin receptor-like proteins that bind to and uptake holo-transferrin.85 Interestingly, hepatocytes are the major source of several iron metabolism-related proteins, including transferrin, lipocalin-2, hemopexin, and hepcidin, playing a key role in controlling bacterial infection.

Transferrin is the major iron-transport protein in the human body and is mainly produced by hepatocytes at high basal levels. The transcription of the transferrin gene is controlled by several liver-enriched transcriptional factors, including C/EBPs and HNFs.86 Transferrin chelates and delivers iron from one tissue to another. Human cells express the transferrin receptor and receive iron via the uptake of the transferrin–iron complex. Transferrin has a very high affinity to iron, 1020 M−1 at pH 7.4.87 Moreover, it is usually maintained at a high concentration in the serum, only 30% saturated.88 Therefore, there are extremely low levels of free iron in the blood for pathogenic microorganisms to utilize. A secondary effect of this iron sequestration might be to inhibit H+-ATPase on the plasma membrane to interfere with the proton gradient, impeding ATP synthesis and disrupting the intracellular pH in the bacteria.89 Because iron is required by almost every organism, transferrin inhibits many pathogens. For example, treatment with transferrin inhibited the growth of S. aureus (Gram-positive), Acinetobacter baumannii (Gram-negative) and C. albicans (fungus) by sequestering iron and disrupting membrane potentials in vitro. Additionally, the infectivity of these pathogens in mice was attenuated by the intravenous administration of human transferrin.90 Transferrin defends against certain fatal pathogens. The growth of Bacillus anthracis, the pathogen that causes anthrax, is efficiently controlled by transferrin so that B. anthracis cannot grow in human serum. This effect was dependent on iron sequestration by transferrin.91 The growth of Staphylococcus epidermidis, an important pathogen for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients, is also impeded by human transferrin. In patients transplanted with hematopoietic stem cells, supplementing transferrin prevented S. epidermidis infection, which occurs when patients have high free iron levels.92 As the main chaperone carrying iron in the circulation, transferrin is also on the front line of sequestrating iron from invading bacteria. Inter-species gene sequencing analysis demonstrated a great evolutionary imprint on the host in avoiding the capture of transferrin by the bacteria specific receptors,93 indicating the high selection pressure and evolutionary success of human transferrin.

Lipocalin-2 was originally identified in neutrophils and was also known as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. As bacteria evolved siderophores to obtain iron from the host, the vertebrae evolved lipocalin-2 to counteract it. Lipocalin-2 binds to the siderophore enterobactin, prohibiting iron uptake by bacteria. Many pathogenic bacteria acquire iron with enterobactin-like siderophores, including E. coli, Salmonella spp., Brucella abortus, B. anthracis, Burkholderia cepacia, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, and Paracoccus spp.94 Accordingly, lipocalin-2 protects mice from E. coli in peritoneal infection and pneumonia models as well as the K. pneumoniae infection model.94,95,96 Despite its initial discovery in neutrophils, using hepatocyte-specific lipocalin-2-deficient mice our laboratory found that 90% of circulating lipocalin-2 is derived from hepatocytes after K. pneumoniae or E. coli infection.97 Hepatocyte-specific lipocalin-2-knockout mice and global lipocalin-2-knockout mice are equally susceptible to bacterial infection, indicating the dominance of hepatocytes in protecting against bacterial infections by producing lipocalin-2.97 Basal serum levels of lipocalin-2 in mice are low (∼62 ng/ml). After bacterial infection, serum lipocalin-2 levels are markedly elevated approximately 100-fold (∼6000 ng/ml). Such high levels of lipocalin-2 are produced by hepatocytes, which is stimulated by IL-6 and downstream STAT3 signaling.97 Because lipocalin-2 and transferrin both sequestrate free iron from the blood, they also orchestrate to inhibit bacterial growth such as K. pneumonia infection.98

Interestingly, lipocalin-2 also modulates the function of innate immune cells. In M. tuberculosis infection, lipocalin-2 may restrain the tuberculosis progress by inhibiting T cell-mediated inflammation and recruiting neutrophils for pathogen clearance. Lipocalin-2 exerted this function by inhibiting CXCL9 but increasing CXCL1 expression.99 During ischemia-reperfusion, lipocalin-2 supports the neutrophil response by enhancing recruitment and reducing apoptosis.100 Lipocalin-2 also promotes M1 macrophage phenotype polarization and inhibits M2 macrophage phenotype polarization by enhancing NF-κB and STAT3 signals.101,102

Heme is another source of iron for invading microorganisms. Hepatocytes produce hemopexin to retain heme from bacteria. Human hemopexin has an extremely high affinity to heme of Kd<1 pM. The in vitro growth of Bacteroides fragilis is efficiently inhibited by hemopexin during the first 24 hours.103 In a cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis model, blood free heme was increased but hemopexinis decreased, causing mortality. Restoring the hemopexin blood concentration suppressed the infection and rescued the mice.104 Additionally, as an immune-modulating protein, hemopexin desensitizes the macrophages from TLR2 and TLR4 stimulation from HMGB1, LPS, and Pam3Cys. Hemopexin treatment reduced the production of IL-6 and TNF-α from both bone marrow-derived macrophages and peritoneal macrophages after TLR stimulation.105,106

Hepcidin (also named LEAP for Liver-Expressed Antimicrobial Peptide) was first known as a peptide that is predominantly produced by hepatocytes and capable of inhibiting bacteria and fungi in vitro.107,108 However, the killing mechanism is unknown, and the contribution of this function in vivo needs to be better defined. Later findings have suggested a central role in iron regulation. By regulating the blood iron concentration, hepcidin suppresses the growth of pathogenic microorganisms in the host.

Hepcidin is a key regulator controlling the serum iron concentration in the human body, playing a central role in the control of iron metabolism. Hepcidin does not interact with iron itself. Instead, hepcidin exerts its function by interacting with ferriportin. Ferriportin is a membrane protein that transfers iron from inside the cells to outside. It is highly expressed in intestinal epithelial cells and macrophages. Intestinal epithelial cells absorb iron from the intestinal lumen and transport it to the capillary with ferriportin, where the iron can further bind to transferrin in the circulation. Macrophages, by contrast, engulf damaged or old red blood cells and reuse the heme iron. They also use ferriportin to transfer iron into the circulation. Hepcidin binds to ferriportin and accelerates its internalization and degradation. Elevated hepcidin decreases the availability of ferriportin, reducing iron assimilation, recycling and, subsequently, blood iron concentration.84,109,110

Because of the central role of iron metabolism, the regulation of hepcidin expression is tightly controlled in hepatocytes. Serum iron directly regulates hepcidin expression. Low iron concentrations lead to reduced hemoglobin production and thus hypoxia in the tissue, which decreases the expression of hepcidin and elevates serum iron concentrations. Because iron sequestration is so important in innate immunity, hepatocytes also respond to inflammatory signals to regulate hepcidin expression. IL-6 is the key regulator in inflammation that increases hepcidin expression. In this scenario, inflammation caused by infection overrides the iron request from the body and induces a large amount of hepcidin production from hepatocytes. High levels of hepcidin further decrease the blood iron concentration by reducing iron assimilation and recycling, subsequently inhibiting iron uptake by the bacteria in the blood. Consequently, bacterial growth is suppressed, and sepsis does not easily occur.84,109,110

In summary, hepatocytes are responsible for the production of most iron-sequestering and -modulating proteins, playing an important role in suppressing bacterial growth via the inhibition of iron uptake by the bacteria.

Fibrinogen and proteinase inhibitors

Fibrinogen, the key factor in the coagulation system, is continuously and almost exclusively produced by hepatocytes.111 Fibrinogen is abundant in blood, approximately 150–350 mg/dl in the healthy individuals, and can be further elevated after the acute phase.111 The basal level of fibrinogen expression in hepatocytes is controlled by several liver-enriched transcription factors (HNF-1, C/EBPs). The acute-phase inflammatory response further upregulates fibrinogen expression in hepatocytes, resulting in plasma fibrinogen level elevation. This inducible fibrinogen expression is mainly controlled by IL-6 and its downstream STAT3 signal.111

The major function of fibrinogen is to form blood clots upon activation by thrombin. Thrombin cleaves fibrinogen into the active fragment fibrin and two peptide fragments, fibrinopeptide A and fibrinopeptide B. The N-terminal 28 amino acids of the β-chain of fibrin after fibrinopeptide B is removed (GHR28) exert antibacterial activity. This activity is highly dependent on the binding capacity of GHR28 to the bacteria and is efficient on Group A and Group B Streptococcus but less efficient on S. aureus and Moraxella catarrhalis. Fibrin binds to the target bacteria and wraps them into a clot, killing the bacteria inside the clot.112 However, fibrinogen has no antibacterial activity against Enterococcus faecalis, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. epidermidis, S. pneumoniae, α-streptococcus, and H. influenza due to the lack of binding to these bacteria.112 In addition, fibrinogen may exert its antibacterial function via the activation of complements. Fibrinogen or fibrin binds to MBL, activating the lectin complement cascade.113 Blood clots formed by fibrin and factor XIII also incorporate complement members including C3 and C1q, subsequently regulating complement activation.114

Fibrinogen mediates the adhesion of monocyte/macrophages and neutrophils. The γ 383-395 segment of the γ chain of fibrinogen, also known as the γP2-C KIIPFNRLTIG sequence,115 is a natural ligand of CD18/CD11b (Mac-1),116 an integrin pair expressed on myeloid leukocytes including monocyte/macrophages and neutrophils. Upon deposition on the extracellular matrix, γP2-C is exposed and fibrinogen can be recognized by αMβ2 integrin to activate leukocytes.117 The integrin αM mediates cell adhesion to fibrinogen, whereas the integrin β2 mediates cell migration and chemotaxis.116 Mn2+ strongly increases the binding of integrin αMβ2 to fibrinogen.118 Losing this binding ability results in failure to recruit these innate immune cells and inefficiency in eliminating S. aureus in an acute infection model.119 More importantly, integrin αMβ2 actively enhances the function of neutrophils. The contact of fibrinogen with integrin αMβ2 extends the lifespan of neutrophils by suppressing the natural caspase cascades.120 Soluble fibrinogen triggers the activation of NF-κB, a critical inhibitor of neutrophil apoptosis. This effect was mediated by FAK-ERK1/2 activation.121 Additionally, the FAK-ERK1/2 pathway mediates secondary granule degranulation and antibody-dependent phagocytosis.122 In genetically modulated mice in which amino acids 390-395 of the fibrinogen γ chain are switched to alanines, myeloid cell recruitment, and pathogen elimination upon acute infection are compromised.123 The above findings prove that fibrinogen plays a supportive role for innate immunity by facilitating bacterial killing via activating complements and recruiting monocytes and neutrophils to the local inflammatory site.

In addition, hepatocytes produce proteinase inhibitors including antitrypsin, antichymotrypsin, α1-cysteine proteinase inhibitor (thiostain), and α2-macroglobulin, which play important roles in activating innate immunity by inactivating proteases released by pathogens and dead or dying cells.124,125,126

Liver-enriched transcription factors that control the basal and inducible levels of innate immunity proteins produced by hepatocytes

Many hepatocyte-derived innate immunity proteins exist at high basal levels in blood from healthy individuals. For example, approximately 150–350 mg/dl fibrinogen, 130 mg/dl complement C3 protein, and 10 mg/dl peptidoglycan-recognition protein-2 (PGLYRP2) are found in the blood from healthy people.11,111,127 The basal levels of hepatocyte-derived innate immunity proteins are controlled by liver-enriched transcription factors including HNFs and C/EBPs. These liver-enriched transcription factors are also upregulated during bacterial infection and acute-phase response, thereby promoting the inducible expression of innate immunity proteins in hepatocytes.

Hepatocyte nuclear factors

HNFs, including HNF-1, HNF-3, HNF-4, and HNF-6, control the transcription of many genes in hepatocytes. HNFs are expressed predominately in the liver but are also expressed and play important roles in regulating gene expression in other tissues. The binding sites for these transcription factors are found in the promoter regions of the majority of hepatocyte-derived innate immunity proteins, controlling the transcription of these proteins. For example, an HNF-1-binding site located in the human fibrinogen promoter region from –47 to –59 bp in combination with other upstream elements is essential for the liver-specific expression of human fibrinogen in hepatocytes.128 HNF-4 plays an important role in the transcription of complement 3.129 Interestingly, the transferrin proximal promoter contains binding sites for HNF-1α, HNF-3α/β, HNF-4α, and HNF-6α, and all are indispensable for transferrin transcription. The coordinated interaction of these factors with the transferrin promoter is required for maximal promoter activity.128

CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins

Several C/EBP family members that are enriched in the liver, including C/EBP-α, C/EBP-β, C/EBP-δ, and C/EBP-ζ, regulate APPs. They share similar or even identical binding elements on the promoter, playing key roles in diverse physiological processes in hepatocytes including the regulation of innate immunity protein expression and acute-phase response.130

In normal and healthy liver, C/EBP-α and C/EBP-ζ are the two predominant forms of C/EBPs in hepatocytes. C/EBP-α controls the basal expression level of many innate immunity proteins in hepatocytes, including complement component C3,131 C6,132 C7,133 SAA,134 and fibrinogen β.135 The critical role of C/EBP-α is supported by the fact that C/EBP-α-knockout mice are almost completely resistant to LPS- or IL-1β-mediated induction of APPs in the liver.136 Unlike C/EBP-α, C/EBP-ζ has minimal transcriptional activity and acts as a dominant-negative regulator of C/EBPs. For example, it binds to the C/EBP binding element on the CRP promoter in the steady state and suppresses CRP expression.137

C/EBP-β is expressed at low levels in hepatocytes of normal and healthy livers but is drastically upregulated during the acute-phase response and inflammation via the activation of NF-κB and/or STAT3.138,139,140 C/EBP-β induces massive expression of innate immunity proteins such as fibrinogen β,141 CRP,137,142 and SAA.143 Moreover, C/EBP-δ is barely expressed in normal, healthy liver but is dramatically induced at an early stage of the acute-phase response. Due to its high transcriptional activity, C/EBP-δ induces extremely high hepatic expression levels and blood concentrations of APPs such as complement component C3131 and SAA.134,143

Cytokines and their downstream signals that activate hepatocytes to produce inducible innate immunity proteins

A variety of cytokines produced mainly by immune cells stimulate hepatocytes to produce APPs that play important roles in ameliorating bacterial infection. These cytokines can be divided into two groups. The first group includes IL-6 and IL-22, which induces APPs via the activation of STAT3 in hepatocytes. The second group includes IL-1β and TNF-α, which predominately activates NF-κB and subsequently augments the expression of many innate immunity proteins in hepatocytes. These two groups likely synergistically induce transcription of many APPs in hepatocytes, playing critical roles in controlling bacterial infection.

Cytokines that activate STAT3, including IL-6 and IL-22

As the direct and most important downstream signal and transcription factor of IL-6, STAT3 is at the center of the regulation of APP production. Recent findings have also suggested that STAT3 is the major downstream signal of IL-22 in upregulating the expression of APPs in hepatocytes.52,144,145 The STAT3 binding element is found in many acute phase anti-bacterial proteins. STAT3 blockade diminishes IL-6-induced production of APPs including SAP, hepcidin, hepatoglobin, and fibrinogen α, β, and γ.146 A study using STAT3 conditional knockout mice categorized the APPs into three groups according to the presence of a STAT3-binding element and C/EBP binding element on their promoters.146 APPs with the STAT3-binding element but not the C/EBP-binding element on their promoters, including fibrinogen α and γ, were completely dependent on the STAT3 signal. Inhibition of the STAT3 signal completely abolishes the induction of these APPs by inflammatory stimulation. APPs with both STAT3 and C/EBP binding sites on their promoters, including fibrinogen β and hepatoglobin, partially rely on the STAT3 signal. Inhibition of STAT3 does not affect the expression of these APPs at early time points, but reduces their expression at later time points. APPs without any STAT3 binding elements on their promoters, such as complement component C3, were completely independent of STAT3.146 Moreover, STAT3 indirectly increases the expression of APPs by forming protein complexes with other transcription factors. For example, the human CRP gene promoter has no STAT3-binding sites. STAT3 protein interacts with HNF-1α and c-Fos to form a transcriptional complex and promote the production of CRP.147 The human SAA gene promoter has no STAT3 binding site, but its expression requires a complex of STAT3, p65, and p300.148

In addition to the direct induction of acute-phase genes, IL-6 also indirectly promotes their expression in hepatocytes via the induction of C/EBP-β and C/EBP-δ expression and activity. C/EBP-β was originally isolated from a rat cDNA library as an IL-6-inducible transcription factor (IL-6-dependent DNA-binding protein; IL6DBP) involved in the induction of several acute-phase response genes.149 IL-6 is one of the most important inducers promoting C/EBP-β gene expression in the liver. The human C/EBP-δ gene promoter contains a STAT3 binding site, and treatment of HepG2 cells with IL-6 leads to rapid induction of C/EBP-δ mRNA.150

Cytokines that activate NF-κB, including IL-1β and TNF-α

NF-κB is another important transcription factor controlling the expression of APPs. The function of NF-κB is the downstream signal of IL-1β, TNF-α, and TLRs. Many APPs including complement component C3 have an NF-κB response element on their promoters, and NF-κB activation upregulates acute inflammation.12,151 IL-1β also indirectly induces anti-bacterial proteins including LBP, SAA2, fibrinogen β, hepatoglobin, and CRP in hepatocytes via the activation of an NF-κB- and C/EBPβ-dependent autocrine IL-6 loop.152 Interestingly, the NF-κB subunit p65 forms a heterodimer with STAT3 and acts either as a suppressor or an activator to regulate the expression of acute-phase genes. P65 interacts with STAT3 and inhibits STAT3 binding to the promoters of class II APP genes. By contrast, the STAT3-p65 dimer enhances the expression of SAA by binding to the NF-κB response element.148 Moreover, the NF-κB subunit p50 and STAT3 appear to cooperate and induce the expression of class II APP genes.153 p50 binds to C/EBPβ to enhance its transcriptional activity, thereby upregulating the expression of acute-phase genes.137,154 Thus, the exact function of the STAT3-p65 dimer depends on the promoter composition of specific APPs, which might explain why IL-1β signaling can increase or decrease the expression of different APPs.

As discussed above, hepatic expression of APPs is upregulated by diverse cytokines that activate either STAT3 or NF-κB, suggesting that both signals play critical roles in the induction of the acute-phase response. A recent study demonstrated that conditional deletion of both NF-κB p65 and STAT3 in hepatocytes, but neither alone, abolished the induction of SAA1, SAA2, SAP, and LBP and exacerbated bacterial infection.155 These results indicate that NF-κB p65 and STAT3 work together to induce maximal acute-phase response and subsequently eliminate bacterial infection.155

Other immune-regulatory functions by hepatocytes

Chemokines produced by hepatocytes

Apart from the APPs, hepatocytes also produce several chemokines (e.g. MCP-1 and CXCL1) to attract innate immune cells (e.g. macrophages and neutrophils) in response to liver damage and bacterial infection.

MCP-1 (also called CCL2) is a powerful chemokine recruiting monocyte/macrophages. Hepatocytes were found to produce MCP-1 in different pathological conditions. In both alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, hepatocytes were found to express MCP-1 and recruit monocyte/macrophages to the liver. This effect devastates steatosis, liver injury, and inflammation.156,157 Moreover, it was reported that hepatocytes can secrete a large amount of CXCL1, which then induces hepatic neutrophil infiltration and causes alcoholic liver injury.158 Given an important role of CXCL1 in inhibiting bacterial infection,159 hepatocyte production of CXCL1 likely contributes to host defense against bacterial infection.

Anti-inflammatory functions of hepatocytes

In addition to production of APPs that promote inflammation, hepatocytes also exhibit important anti-inflammatory functions. By doing this, hepatocytes protect the host from overwhelming and unnecessary inflammation, as well as from the cytotoxic immune molecules.

PGLYRP2 is an important immunomodulatory protein predominantly expressed by hepatocytes. Unlike other members of PGLYRP family (PGLYRP1, PGLYRP3, and PGLYRP4, which are expressed by immune cells and epithelial cells), PGLYRP2 does not harbor bactericidal activity. Instead, PGLYRP2 is an amidase. It hydrolyzes the partially degraded or single layer peptidoglycan to smaller fragments, thereby preventing the bacterial peptidoglycan recognizing by TLRs from the immune cells.160,161 Hepatocytes also express TLR4, which mediates the clearance of LPS in the blood after the killing of bacteria.162 This way, hepatocytes eliminate immune stimulatory molecules from both dead Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria to prevent septic shock downstream of the inflammatory reaction to the bacterial debris.

Tolerogenic effect of hepatocytes

The liver is known as a unique organ to exert tolerogenic effect on the immune system. Hepatocytes are found to participate in the modulation of the adaptive immune system, along with many other nonparenchymal cells in the liver. In pathological conditions, hepatocytes express MHC class I and II,163 but they do not express critical co-stimulatory factors, CD80 and CD86.164 Therefore, hepatocytes cannot induce the sustained activation and survival of T cells and finally T cells undergo passive cell death.164,165 Moreover, hepatocytes can also express PD-L1 in the presence of type I and type II IFNs.166 Because PD-L1 is a powerful ligand to induce apoptosis of T cells, this might be another mechanism of liver tolerance induced by hepatocytes.

Dysregulation of innate immunity protein production by hepatocytes

Although production of innate immunity proteins by hepatocytes is well documented, how these proteins are dysregulated and how this dysregulation contributes to an increased risk of bacterial infection in chronic liver disease have not been carefully studied, and translation of these findings into new therapeutics has been modest. In general, patients with cirrhosis have elevated circulating acute phase and innate immunity proteins. However, evidence suggests that many of these patients have defective acute-phase responses to bacterial infection, contributing to an increased susceptibility to bacterial infection.167,168 For example, although patients with liver dysfunction or liver cirrhosis still produce APPs, their levels are markedly lower during bacteremia than patients without liver dysfunction.168,169 As further evidence of defective acute-phase response in cirrhotic patients, these patients have high circulating IL-6 but poor acute-phase response.170 In addition, a recent study reported that mice with high-fat and high-cholesterol diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) have increased production of cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) and APPs but respond poorly to a low dose of LPS-induced production of APPs.171 This dysfunctional innate immunity protein production in the presence of NASH may contribute to the increased bacterial infection susceptibility of NASH patients.172

Several genes encoding hepatocyte-derived innate immunity proteins have polymorphisms that significantly affect the production of these proteins. For example, the human mannose-binding lectin 2 (MBL2) gene has several single nucleotide polymorphisms that significantly affect the production of MBL in hepatocytes,16 resulting in MBL deficiency in 5–30% of the population depending on ethnicity.173 MBL is a key activator of the lectin complement pathway, and people with MBL deficiency have an increased risk of bacterial infection.173 To overcome the MBL deficiency, MBL replacement therapy by using plasma-derived or recombinant MBL has been tested in several pre-clinical and clinical studies in patients. However, the results from these studies have been mixed due to several reasons, such as the use of different definitions of MBL deficiency, the use of different outcome parameters, and the context of MBL in the different disease processes.174 Large multicenter trials should be conducted to confirm the viability and efficacy of MBL replacement therapy.

Concluding remarks

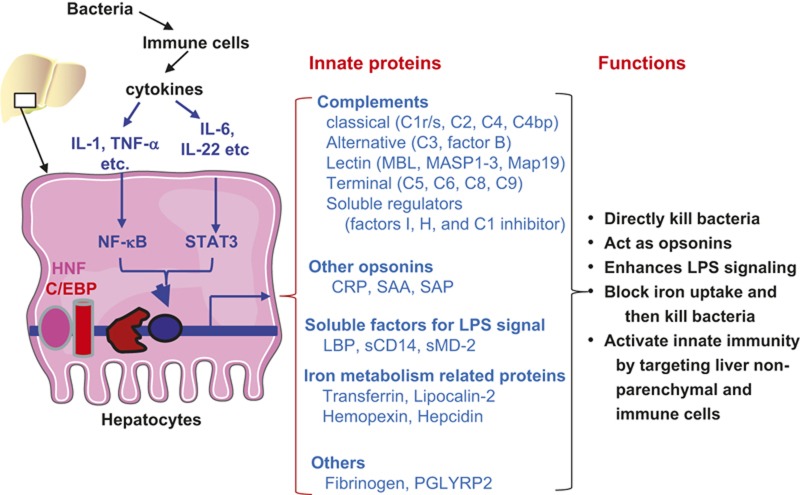

In summary, hepatocytes play a vital role in innate immunity against bacterial infection by producing a wide variety of innate immunity proteins (Figure 1). These hepatocyte-derived innate immunity proteins control bacterial infection via diverse mechanisms. First, hepatocytes produce bactericidal proteins (e.g. complement proteins) that directly kill bacteria. Second, hepatocytes are the major source of the production of many opsonins (complement proteins, CRP, SAA, SAP) that assist in the phagocytosis of foreign bacteria. Third, several important components of the LPS signaling pathways are primarily produced by hepatocytes, including LBP, sCD14, and sMD-2. These proteins play key roles in regulating the LPS-mediated activation of innate immunity. Fourth, hepatocytes produce key iron metabolism-related proteins (transferrin, lipocalin-2, hemopexin, hepcidin) that constrain bacterial growth via the inhibition of iron uptake by bacteria. Fifth, the coagulation factor fibrinogen, which is mainly produced by hepatocytes, also indirectly kills bacteria by activating complements and by recruiting neutrophils to the local inflammatory site. Finally, in addition to direct killing pathogens, many innate immunity proteins produced by hepatocytes also regulate host defense against pathogen infection by interacting with liver non-parenchymal cells and immune cells.

Figure 1.

Critical roles of hepatocytes in anti-bacterial innate immunity. Upon bacterial infection, immune cells secrete cytokines to stimulate hepatocytes to produce anti-bacterial proteins. The pro-inflammatory cytokines activate the transcription factors NF-κB and STAT3. Along with liver-enriched transcription factors HNFs and C/EBPs, they promote the expression of many anti-bacterial proteins as listed. These proteins eliminate the bacteria and orchestrate the innate immune function.

Hepatocytes not only constitutively produce several innate immunity proteins at high basal levels but also respond to bacterial infection to synthesize additional innate immunity proteins. Expression of these basal and inducible innate immunity proteins in hepatocytesis controlled by liver-enriched transcriptional factors (e.g. HNFs, C/EBPs), pro-inflammatory cytokines, and their downstream signaling pathways (e.g. NF-κB and STAT3). Using microarray analyses, Quinton et al.155 reported that deletion of both NF-κB p65 and STAT3 in hepatocytes, but neither alone, abolished the upregulation of a wide variety of genes induced by bacterial infection, including 22 well-known APPs and 149 potentially secreted proteins. Some of those secreted proteins likely contribute to the activation of innate immunity. However, further studies are required to confirm their functions and expand the list of hepatocyte-derived innate immunity proteins described in the current review.

Given the vital role of hepatocytes in producing innate immunity proteins and controlling bacterial infection, chronic liver disease, especially cirrhosis, is associated with impaired hepatocyte function and reduced ability to produce innate immunity proteins in response to bacterial infection, leading to the increased susceptibility of cirrhotic patients to bacterial infection. Further translational studies on the dysregulation of innate immunity protein production by hepatocytes may identify therapeutic targets for the treatment of bacterial infection associated with chronic liver disease.

Footnotes

The work from the authors' lab described in the current review was supported by the intramural program of NIAAA, NIH (B.G.)

References

- Gao B, Jeong WI, Tian Z. Liver: an organ with predominant innate immunity. Hepatology 2008; 47: 729–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincon M. Interleukin-6: from an inflammatory marker to a target for inflammatory diseases. Trends Immunol 2012; 33: 571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese LH, Rose-John S. IL-6 biology: implications for clinical targeting in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014; 10: 720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris CA, He M, Kang LI, Ding MQ, Radder JE, Haynes MM et al. Synthesis of IL-6 by hepatocytes is a normal response to common hepatic stimuli. PLoS One 2014; 9: e96053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27: 519–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder C. Mechanisms of interleukin-1beta release. Immunobiology 2009; 214: 543–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode JG, Albrecht U, Haussinger D, Heinrich PC, Schaper F. Hepatic acute phase proteins--regulation by IL-6- and IL-1-type cytokines involving STAT3 and its crosstalk with NF-kappaB-dependent signaling. Eu J Cell Biol 2012; 91: 496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holers VM. Complement and its receptors: new insights into human disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2014; 32: 433–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarma JV, Ward PA. The complement system. Cell Tissue Res 2011; 343: 227–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X, Gao B. The complement system in liver diseases. Cell Mol Immunol 2006; 3: 333–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alper CA, Johnson AM, Birtch AG, Moore FD. Human C'3: evidence for the liver as the primary site of synthesis. Science 1969; 163: 286–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volanakis JE. Transcriptional regulation of complement genes. Annu Rev Immunol 1995; 13: 277–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan BP, Gasque P. Extrahepatic complement biosynthesis: where, when and why? Clin Exp Immunol 1997; 107: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris KM, Aden DP, Knowles BB, Colten HR. Complement biosynthesis by the human hepatoma-derived cell line HepG2. J Clin Invest 1982; 70: 906–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alper CA, Johnson AM, Birtch AG, Moore FD. Human C'3: evidence for the liver as the primary site of synthesis. Science 1969; 163: 286–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwman LH, Roos A, Terpstra OT, de Knijff P, van Hoek B, Verspaget HW et al. Mannose binding lectin gene polymorphisms confer a major risk for severe infections after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology 2005; 129: 408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaeble W, Dahl MR, Thiel S, Stover C, Jensenius JC. The mannan-binding lectin-associated serine proteases (MASPs) and MAp19: four components of the lectin pathway activation complex encoded by two genes. Immunobiology 2002; 205: 455–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover CM, Lynch NJ, Hanson SJ, Windbichler M, Gregory SG, Schwaeble WJ. Organization of the MASP2 locus and its expression profile in mouse and rat. Mamm Genome 2004; 15: 887–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Invest 2003; 111: 1805–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen RF. C-reactive protein, inflammation, and innate immunity. Immunol Res 2001; 24: 163–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black S, Kushner I, Samols D. C-reactive protein. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 48487–48490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inatsu A, Kinoshita M, Nakashima H, Shimizu J, Saitoh D, Tamai S et al. Novel mechanism of C-reactive protein for enhancing mouse liver innate immunity. Hepatology 2009; 49: 2044–2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelena J, Altamirano J, Abraldes JG, Affo S, Morales-Ibanez O, Sancho-Bru P et al. Systemic inflammatory response and serum lipopolysaccharide levels predict multiple organ failure and death in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2015; 62: 762–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund KK, Niemi K, Kovanen PT. Immune functions of serum amyloid A. Crit Rev Immunol 2012; 32: 335–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LE, Whitehead AS. Regulation of serum amyloid A protein expression during the acute-phase response. Biochem J 1998; 334: 489–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah C, Hari-Dass R, Raynes JG. Serum amyloid A is an innate immune opsonin for Gram-negative bacteria. Blood 2006; 108: 1751–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander LE, Sackett SD, Dierssen U, Beraza N, Linke RP, Muller M et al. Hepatic acute-phase proteins control innate immune responses during infection by promoting myeloid-derived suppressor cell function. J Exp Med 2010; 207: 1453–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Kim MK, Park KS, Shin EH, Jo SH, Kim SD et al. Serum amyloid A induces contrary immune responses via formyl peptide receptor-like 1 in human monocytes. Mol Pharmacol 2006; 70: 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He R, Sang H, Ye RD. Serum amyloid A induces IL-8 secretion through a G protein-coupled receptor, FPRL1/LXA4R. Blood 2003; 101: 1572–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He RL, Zhou J, Hanson CZ, Chen J, Cheng N, Ye RD. Serum amyloid A induces G-CSF expression and neutrophilia via Toll-like receptor 2. Blood 2009; 113: 429–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ather JL, Ckless K, Martin R, Foley KL, Suratt BT, Boyson JE et al. Serum amyloid A activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and promotes Th17 allergic asthma in mice. J Immunol 2011; 187: 64–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Kim SD, Shim JW, Lee SY, Lee H, Cho KH et al. Serum amyloid A induces CCL2 production via formyl peptide receptor-like 1-mediated signaling in human monocytes. J Immunol 2008; 181: 4332–4339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandri S, Hatanaka E, Franco AG, Pedrosa AM, Monteiro HP, Campa A. Serum amyloid A induces CCL20 secretion in mononuclear cells through MAPK (p38 and ERK1/2) signaling pathways. Immunol Lett 2008; 121: 22–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste J, Botto M, Bottoms SE, Brown JS. Serum amyloid P aids complement-mediated immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae. PLoS Pathog 2007; 3: 1208–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochrietor JD, Harrison KA, Zahedi K, Mortensen RF. Role of STAT3 and C/EBP in cytokine-dependent expression of the mouse serum amyloid P-component (SAP) and C-reactive protein (CRP) genes. Cytokine 2000; 12: 888–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YJ, Doni A, Skjoedt MO, Honore C, Arendrup M, Mantovani A et al. Heterocomplexes of mannose-binding lectin and the pentraxins PTX3 or serum amyloid P component trigger cross-activation of the complement system. J Biol Chem 2011; 286: 3405–3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mold C, Gresham HD, Du Clos TW. Serum amyloid P component and C-reactive protein mediate phagocytosis through murine Fc gamma Rs. J Immunol 2001; 166: 1200–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj D, Mold C, Markham E, Du Clos TW. Serum amyloid P component binds to Fc gamma receptors and opsonizes particles for phagocytosis. J Immunol 2001; 166: 6735–6741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mold C, Baca R, Du Clos TW. Serum amyloid P component and C-reactive protein opsonize apoptotic cells for phagocytosis through Fcgamma receptors. J Autoimmun 2002; 19: 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijl M, Horst G, Bijzet J, Bootsma H, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CG. Serum amyloid P component binds to late apoptotic cells and mediates their uptake by monocyte-derived macrophages. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 48: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickerstaff MC, Botto M, Hutchinson WL, Herbert J, Tennent GA, Bybee A et al. Serum amyloid P component controls chromatin degradation and prevents antinuclear autoimmunity. Nat Med 1999; 5: 694–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Singh PP. Serum amyloid P-component-mediated inhibition of the uptake of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by macrophages, in vitro. Scand J Immunol 2004; 59: 425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PP, Kaur S. Serum amyloid P-component in murine tuberculosis: induction kinetics and intramacrophage Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth inhibition in vitro. Microbes Infect/Institut Pasteur 2006; 8: 541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haas CJ, van Leeuwen EM, van Bommel T, Verhoef J, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA. Serum amyloid P component bound to gram-negative bacteria prevents lipopolysaccharide-mediated classical pathway complement activation. Infect Immun 2000; 68: 1753–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noursadeghi M, Bickerstaff MC, Gallimore JR, Herbert J, Cohen J, Pepys MB. Role of serum amyloid P component in bacterial infection: protection of the host or protection of the pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000; 97: 14584–14589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox N, Pilling D, Gomer RH. Distinct Fcgamma receptors mediate the effect of serum amyloid p on neutrophil adhesion and fibrocyte differentiation. J Immunol 2014;193: 1701–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LA, Chen Q, Kramer MS, Hesson DP, Argentieri RL, Peng X et al. TGF-beta driven lung fibrosis is macrophage dependent and blocked by Serum amyloid P. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2011; 43: 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LA, Rosada R, Moreira AP, Joshi A, Kramer MS, Hesson DP et al. Serum amyloid P therapeutically attenuates murine bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via its effects on macrophages. PLoS One 2010; 5: e9683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Xu W, Xiong S. Macrophage differentiation and polarization via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-ERK signaling pathway conferred by serum amyloid P component. J Immunol 2011; 187: 1764–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castano AP, Lin SL, Surowy T, Nowlin BT, Turlapati SA, Patel T et al. Serum amyloid P inhibits fibrosis through Fc gamma R-dependent monocyte-macrophage regulation in vivo. Sci Transl Med 2009; 1: 5ra13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschning CJ, Unbehaun A, Fiedler G, Hallatschek W, Lamping N, Pfeil D et al. The transcriptional activation pattern of lipopolysaccharide binding protein (LBP) involving transcription factors AP-1 and C/EBP beta. Immunobiology 1997; 198: 124–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk K, Witte E, Hoffmann U, Doecke WD, Endesfelder S, Asadullah K et al. IL-22 induces lipopolysaccharide-binding protein in hepatocytes: a potential systemic role of IL-22 in Crohn's disease. J Immunol 2007; 178: 5973–5981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschning C, Unbehaun A, Lamping N, Pfeil D, Herrmann F, Schumann RR. Control of transcriptional activation of the lipopolysaccharide binding protein (LBP) gene by proinflammatory cytokines. Cytokines Cell Mol Ther 1997; 3: 59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su GL, Dorko K, Strom SC, Nussler AK, Wang SC. CD14 expression and production by human hepatocytes. J Hepatol 1999; 31: 435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bas S, Gauthier BR, Spenato U, Stingelin S, Gabay C. CD14 is an acute-phase protein. J Immunol 2004; 172: 4470–4479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z, Zhou L, Hetherington CJ, Zhang DE. Hepatocytes contribute to soluble CD14 production, and CD14 expression is differentially regulated in hepatocytes and monocytes. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 36430–36435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Shapiro RA, Nie S, Zhu D, Vodovotz Y, Billiar TR. Characterization of rat CD14 promoter and its regulation by transcription factors AP1 and Sp family proteins in hepatocytes. Gene 2000; 250: 137–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissieres P, Dunn-Siegrist I, Schappi M, Elson G, Comte R, Nobre V et al. Soluble MD-2 is an acute-phase protein and an opsonin for Gram-negative bacteria. Blood 2008; 111: 2122–2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissieres P, Araud T, Ochoda A, Drifte G, Dunn-Siegrist I, Pugin J. Cooperation between PU.1 and CAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta is necessary to induce the expression of the MD-2 gene. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 26261–26272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann RR, Kirschning CJ, Unbehaun A, Aberle HP, Knope HP, Lamping N et al. The lipopolysaccharide-binding protein is a secretory class 1 acute-phase protein whose gene is transcriptionally activated by APRF/STAT/3 and other cytokine-inducible nuclear proteins. Mol Cell Biol 1996; 16: 3490–3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J. Bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI) and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP): structure, function and regulation in host defence against Gram-negative bacteria. Biochem Soc Trans 2003; 31: 785–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan MH, Klein RD, Steinstraesser L, Merry AC, Nemzek JA, Remick DG et al. An essential role for lipopolysaccharide-binding protein in pulmonary innate immune responses. Shock 2002; 18: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack RS, Fan X, Bernheiden M, Rune G, Ehlers M, Weber A et al. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein is required to combat a murine gram-negative bacterial infection. Nature 1997; 389: 742–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang KK, Dorner BG, Merkel U, Ryffel B, Schutt C, Golenbock D et al. Neutrophil influx in response to a peritoneal infection with Salmonella is delayed in lipopolysaccharide-binding protein or CD14-deficient mice. J Immunol 2002; 169: 4475–4480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp S, de Vos AF, Florquin S, Golenbock DT, van der Poll T. Lipopolysaccharide binding protein is an essential component of the innate immune response to Escherichia coli peritonitis in mice. Infect Immun 2003; 71: 6747–6753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roy D, Di Padova F, Tees R, Lengacher S, Landmann R, Glauser MP et al. Monoclonal antibodies to murine lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein (LBP) protect mice from lethal endotoxemia by blocking either the binding of LPS to LBP or the presentation of LPS/LBP complexes to CD14. J Immunol 1999; 162: 7454–7460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann RR. Old and new findings on lipopolysaccharide-binding protein: a soluble pattern-recognition molecule. Biochem Soc Trans 2011; 39: 989–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreugdenhil AC, Rousseau CH, Hartung T, Greve JW, van 't Veer C, Buurman WA. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein mediates LPS detoxification by chylomicrons. J Immunol 2003; 170: 1399–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber JR, Freyer D, Alexander C, Schroder NW, Reiss A, Kuster C et al. Recognition of pneumococcal peptidoglycan: an expanded, pivotal role for LPS binding protein. Immunity 2003; 19: 269–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder NW, Heine H, Alexander C, Manukyan M, Eckert J, Hamann L et al. Lipopolysaccharide binding protein binds to triacylated and diacylated lipopeptides and mediates innate immune responses. J Immunol 2004; 173: 2683–2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder NW, Morath S, Alexander C, Hamann L, Hartung T, Zahringer U et al. Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus activates immune cells via toll-like receptor (TLR)-2, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), and CD14, whereas TLR-4 and MD-2 are not involved. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 15587–15594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branger J, Florquin S, Knapp S, Leemans JC, Pater JM, Speelman P et al. LPS-binding protein-deficient mice have an impaired defense against Gram-negative but not Gram-positive pneumonia. Int Immunol 2004; 16: 1605–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller M, Stamme C, Draing C, Hartung T, Seydel U, Schromm AB. Cell activation of human macrophages by lipoteichoic acid is strongly attenuated by lipopolysaccharide-binding protein. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 31448–31456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann C, Spreitzer I, Schroder NW, Morath S, Lehner MD, Fischer W et al. Cytokine induction by purified lipoteichoic acids from various bacterial species—role of LBP, sCD14, CD14 and failure to induce IL-12 and subsequent IFN-gamma release. Eur J Immunol 2002: 32: 541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damien P, Cognasse F, Eyraud MA, Arthaud CA, Pozzetto B, Garraud O et al. LPS stimulation of purified human platelets is partly dependent on plasma soluble CD14 to secrete their main secreted product, soluble-CD40-Ligand. BMC Immunol 2015; 16: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno C, Merino J, Ramirez N, Echeverria A, Pastor F, Sanchez-Ibarrola A. Lipopolysaccharide needs soluble CD14 to interact with TLR4 in human monocytes depleted of membrane CD14. Microb Infect/Institut Pasteur 2004; 6: 990–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai Y, Makimura Y, Kawabata A, Ogawa T. Soluble CD14 discriminates slight structural differences between lipid as that lead to distinct host cell activation. J Immunol 2007; 179: 7674–7683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi T, Muroi M, Tanamoto K. Inhibitory effects of soluble MD-2 and soluble CD14 on bacterial growth. Microbiol Immunol 2010; 54: 74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchens RL, Thompson PA, Viriyakosol S, O'Keefe GE, Munford RS. Plasma CD14 decreases monocyte responses to LPS by transferring cell-bound LPS to plasma lipoproteins. J Clin Invest 2001; 108: 485–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacque B, Stephan K, Smirnova I, Kim B, Gilling D, Poltorak A. Mice expressing high levels of soluble CD14 retain LPS in the circulation and are resistant to LPS-induced lethality. Eur J Immunol 2006; 36: 3007–3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranoa DR, Kelley SL, Tapping RI. Human lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP) and CD14 independently deliver triacylated lipoproteins to toll-like receptor 1 (TLR1) and TLR2 and enhance formation of the ternary signaling complex. J Biol Chem 2013; 288: 9729–9741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puertollano MA, Puertollano E, de Cienfuegos GA, de Pablo MA. Dietary antioxidants: immunity and host defense. Current Topics Med Chem 2011; 11: 1752–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintergerst ES, Maggini S, Hornig DH. Contribution of selected vitamins and trace elements to immune function. Ann Nutr Metab 2007; 51: 301–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakesmith H, Prentice AM. Hepcidin and the iron-infection axis. Science 2012;338: 768–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomme PT, McCann KB, Bertolini J. Transferrin: structure, function and potential therapeutic actions. Drug Discov Today 2005; 10: 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakin MM. Regulation of transferrin gene expression. FASEB J 1992; 6: 3253–3258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisen P, Leibman A, Zweier J. Stoichiometric and site characteristics of the binding of iron to human transferrin. J Biol Chem 1978; 253: 1930–1937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenroth BE, Steere AN, Chasteen ND, Everse SJ, Mason AB. How the binding of human transferrin primes the transferrin receptor potentiating iron release at endosomal pH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108: 13089–13094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres MT, Fierro JF. Antimicrobial mechanism of action of transferrins: selective inhibition of H+-ATPase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54: 4335–4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Pantapalangkoor P, Tan B, Bruhn KW, Ho T, Nielsen T et al. Transferrin iron starvation therapy for lethal bacterial and fungal infections. J Infect Dis 2014; 10: 254–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooijakkers SH, Rasmussen SL, McGillivray SM, Bartnikas TB, Mason AB, Friedlander AM et al. Human transferrin confers serum resistance against Bacillus anthracis. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 27609–27613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bonsdorff L, Sahlstedt L, Ebeling F, Ruutu T, Parkkinen J. Apotransferrin administration prevents growth of Staphylococcus epidermidis in serum of stem cell transplant patients by binding of free iron. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2003; 37: 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber MF, Elde NC. Nutritional immunity. Escape from bacterial iron piracy through rapid evolution of transferrin. Science 2014, 346: 1362–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S, Rodriguez DJ, Holmes MA, Strong RK et al. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature 2004; 432: 917–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Santoni-Rugiu E, Ralfkiaer E, Porse BT, Moser C, Hoiby N et al. Lipocalin 2 is protective against E. coli pneumonia. Respir Res 2010; 11: 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman MA, Oyler JE, Burns SH, Caza M, Lepine F, Dozois CM et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae yersiniabactin promotes respiratory tract infection through evasion of lipocalin 2. Infect Immun 2011; 79: 3309–3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu MJ, Feng D, Wu H, Wang H, Chan Y, Kolls J et al. Liver is the major source of elevated serum lipocalin-2 levels after bacterial infection or partial hepatectomy: a critical role for IL-6/STAT3. Hepatology 2015; 61: 692–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman MA, Lenio S, Schmidt L, Oyler JE, Weiser JN. Interaction of lipocalin 2, transferrin, and siderophores determines the replicative niche of Klebsiella pneumoniae during pneumonia. mBio 2012; 3: pii: e00224–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]