Abstract

Background

Hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) fellowships in North America are difficult to secure with an acceptance rate of 1 in 3 applicants. Desirable characteristics in an HPB surgery applicant have not been previously reported. This study examines the perceptions of trainees and HPB program directors with regards to positive attributes in applicants for HPB fellowships.

Methods

Parallel surveys were distributed by email with a web-link to current and recent HPB fellows in North America (from the past 5 years) with questions addressing the following domains: surgical training, research experience, and mentorship. A similar survey was distributed to HPB fellowship program directors in North America requesting their opinion as to the importance of these characteristics in potential applicants.

Results

32 of 60 of surveyed fellows and 21 of 38 of surveyed program directors responded between November 2014–February 2015. Fellows overall came from fairly diverse backgrounds (13/32 were overseas medical graduates) about one third of respondents having had some prior research experience. Program directors gave priority to the applicant's interview, curriculum vitae, and their recommendation letters (in order of importance). Both the surveyed fellows and program directors felt that the characteristics most important in a successful HPB fellowship candidate include interpersonal skills, perceived operative skills, and perceived fund of knowledge.

Conclusion

Results of this survey provide useful and practical information for trainees considering applying to an HPB fellowship program.

Introduction

Hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) surgery encompasses the care of benign and malignant disease processes involving the liver, pancreas, and biliary systems. Over the last few decades, as with other surgical specialties (which have moved to an organ based approach), HPB surgery has become its own distinct focus of practice. In North America, advanced training paradigms that include HPB surgery are available through the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS), the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO), and the Americas Hepato-pancreato-biliary Association (AHPBA) fellowships. AHPBA, in conjunction with the Fellowship Council, currently offers 26 fellowship positions across the United States and Canada. Twenty one programs offer HPB only training (11 one-year programs and 10 two-year programs), three offer HPB training embedded within the SSO training model, and two offer HPB training that is embedded within the ASTS training model (all combined programs are two years in length).1

Recent data suggest that almost 80% of graduating general surgery residents will pursue fellowship training.2 Although HPB fellowship specific data are not available since some applicants apply for several fellowship types, the Fellowship Council reports the unmatched applicant percentage for minimally invasive and gastrointestinal surgery fellowships ranges from 18 to 36% (years 2004–2014). The range increases to 29–36% if only the last four years of available data are considered.3 The suggestion is that the match rate for HPB fellowships is even more competitive than others, and the applicant numbers are increasing every year. These realities highlight the intensely competitive environment current residents enter as they seek fellowship training.

Previous studies have sought to define the factors leading to success in the pediatric and endocrine surgery match processes.4, 5 Even though HPB fellowship positions seem to be at a premium, there are no objective data available to help guide applicants considering application for HPB fellowship. In this study, successfully matched fellows were queried to assess the characteristics of successful applicants and HPB program directors were similarly asked to measure the perceived importance of each domain. The principal aim of this study, was to examine if the perception of HPB program directors regarding the qualities of successful HPB applicants corresponded to the reality of actual matched fellows.

Methods

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained (Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, NC) and anonymous, self-reported survey data were collected from respondents replying to e-mails sent on the authors' behalf by the AHPBA in November of 2014. Two web-based surveys were generated to capture responses from HPB surgery fellows and HPB fellowship program directors. All fellow respondents were AHPBA members and included current and former fellows within five years of fellowship completion. Surveyed program directors (PD) and assistant program directors were included based on those HPB fellowship programs in good standing with the Fellowship Council within the United States or Canada. Surveys were available November 2014–February 2015 via a web-link in the distributed emails. The goal survey response rate was set at 50% as rates greater than 50% are associated with participation methods in excess of our distribution model.6, 7, 8, 9

Data were collected using the web-based survey collection tool, SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey Inc. Palo Alto, CA. www.surveymonkey.com). The fellows' survey included 33 questions including dichotomous, nominal, ranked, and open-ended question types. The PD survey comprised 25 questions including dichotomous, ranked, open-ended, and seven point Likert-scale questions, which ranged from “Not at All Important” to “Extremely Important”. Open ended questions were most often triggered in response to a previous question to obtain more specific information about a particular question. Question content was similar in both groups so a meaningful comparison could be made. Question content categories included background, residency, and interview/application characteristics.

Response analysis

Nominal and dichotomous data were presented as percentages of total responses for that particular question. Ranked responses were calculated using weighted answer choices, where the highest ranked choice was assigned a value of seven and the lowest a value of one. Therefore, the answer choice with the largest ranking average was the most preferred choice and was presented as such.10 Likert-scale questions (PD survey only) were calculated using weighted answer choices as well, where the answer choice “Not at all important” was assigned a weight of one, and “Extremely important” was weighted to a value of seven. From this, an average rating can be calculated and can give a sense of the overall importance assigned to a particular answer choice. Weighted answers were calculated using the equation below, where w = weight of the answer choice and x = response count for an answer choice. Data were tabulated and graphs generated using Microsoft Office Excel®, v. 2010.

Equation for the calculation of weighted answer choices, both ranked and Likert-scale question types.

Results

Thirty-two of 60 fellows responded along with 21 of 38 program or assistant program directors with an overall response rate of 54%. Table 1 summarizes the fellow responses and documents medical school graduation, fellowship training, type of residency program and ABSITE (American Board of Surgery in Training Exam) percentile score. Research productivity and experience, operative experience during residency training, as well as other fellowship program applied to are similarly provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected responses, fellow's survey, N = 32a

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Medical school | ||

| United States | 12 | 37.5 |

| Canada | 7 | 21.9 |

| Other | 13 | 40.6 |

| Residency | ||

| Completed in the United States | 20 | 62.5 |

| Type: | ||

| Academic | 17 | 53.1 |

| Hybrid | 15 | 46.9 |

| ABSITE score | ||

| <50% | 3 | 9.7 |

| 50–75% | 8 | 25.8 |

| 75–90% | 5 | 16.1 |

| >90% | 5 | 16.1 |

| N/A | 10 | 32.3 |

| Cases completed during residency | ||

| All case types | ||

| <750 | 3 | 10.0 |

| 750–1000 | 11 | 36.7 |

| 1000–1500 | 12 | 40.0 |

| >1500 | 4 | 13.3 |

| HPB cases | ||

| <20 | 12 | 38.7 |

| 20–40 | 11 | 35.5 |

| >40 | 8 | 25.8 |

| Research | ||

| Research required during residency | 10 | 32.3 |

| Peer reviewed publications – all topics | ||

| ≤10 | 16 | 51.6 |

| >10 | 15 | 48.4 |

| Peer reviewed publications – HPB related | ||

| ≤10 | 26 | 83.9 |

| >10 | 5 | 16.1 |

| Peer reviewed publications – First author | ||

| ≤10 | 25 | 80.6 |

| >10 | 6 | 19.4 |

| Oral or poster presentation – all topics | ||

| ≤10 | 15 | 48.4 |

| >10 | 16 | 51.6 |

| Fellowship application characteristics | ||

| Applied for SSOƨ | 7 | 70.0 |

| Applied for ASTS£ | 3 | 30.0 |

| Other | ||

| Mentored by HPB surgeon | 22 | 73.3 |

| Completed previous fellowship | 9 | 29.0 |

| Held a leadership role: | ||

| Administrative chief | 21 | 91.3 |

| Hospital committee membership | 17 | 73.9 |

| Had prospective job at time of application and interviews | 13 | 43.3 |

| Advanced degrees held (MPH, MS, PhD) | 13 | 40.6 |

Respondents did not provide answers to some questions, omitted by choice, ƨ Society of Surgical Oncology, £ American Society of Transplant Surgery.

Fig. 1 provides a summary of the number of programs the fellows applied to, received interviews from, completed interviews at, and ranked for the match. Less than one third of fellows had completed a previous fellowship prior to applying for HPB surgery fellowship (four in transplant surgery, two in surgical oncology, and two minimally invasive fellowships). Eight fellows had practiced general surgery, transplant surgery or bariatric and gastrointestinal surgery prior to applying for an HPB fellowship. The mean number of years in practice was 2.2.

Figure 1.

Summary of fellows' responses regarding number or programs applied to, interviews offered and attended, and programs ranked

Less than half of fellows 13/32 indicated they had a prospective job at the time of fellowship application and interviews. Twenty-three of the 30 fellows planned to apply for an academic position following fellowship training and four in private practice. Outcome was not known for two and one fellow intended to apply for an international position. Twenty-two fellows indicated they were mentored during their residency by an HPB surgeon.

Program director survey responses

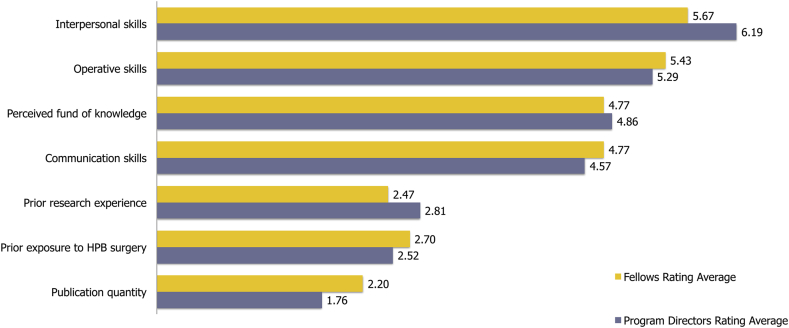

When asked to rank the qualities and characteristics perceived to be the most valuable in an HPB fellowship applicant (Fig. 2), PD and fellows responded similarly. Interpersonal skills were most important, followed by perceived operative skills, and then perceived fund of knowledge. PD and fellows both rated publication quantity as the least important quality. Fig. 3 summarizes the PD averaged responses. The strength of the applicant's interview, curriculum vitae (CV), and letters of recommendation were felt to be of the most importance to the PD. Table 2 records the relative importance attributed by PD to each factor. The vast majority of PD (89.5%) responded that they would not negatively view an applicant that had applied to other fellowships.

Figure 2.

Average rating (scale 1–7) of HPB fellowship applicant desired qualities and characteristics. Higher average rating indicates a stronger preference for the quality or characteristic

Figure 3.

Summary of average importance (scale 1–7) of various characteristics of applicants by program directors. Higher average rating indicates a stronger degree of reported importance for the quality or characteristic

Table 2.

Response of program directors regarding the importance of an HPB fellowship applicant's interview, CV, and recommendation letters

| Neutral | Moderately important | Very important | Extremely important | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation letters | 4.8% | 14.3% | 66.7% | 14.3% |

| Interview | 0% | 4.8% | 57.1% | 38.1% |

| CV | 0% | 14.3% | 66.7% | 19.0% |

** Values are based off a 7 point Likert scale. Note no respondents reported any of the above values were not at all important, of low importance, or slightly important.

By compiling the most common responses of the fellows, it is possible to construct a picture of the “typical” successful HPB surgery fellowship applicant (Table 3). Contrasting the characteristics of the “typical” successful applicant and the importance placed on these characteristics by the PD (Fig. 3), one can appreciate that the reality and perception of a successful applicant are similar.

Table 3.

Characteristics of successfully matched HPB fellows – most frequent responses from fellows

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Additional write in comments from program directors highlight important characteristics in successful applicants:

-

•

“We really look for someone that will be easy to work with and who wants to be [at our institution].”

-

•

“One can NEVER assess operative skills by ANY paper trail. At best, comments on such skills are circumstantial. Comments on [operative skills] are the least reliable of all application material.”

Discussion

This is the first study of its kind to examine the favorable aspects of a successful applicant for HPB fellowship training. The data show that the most important qualities in an HPB fellow, as ranked by both PD and fellows, are interpersonal and perceived operative skills, closely followed by perceived fund of knowledge and communication skills. This indicates the correct insight that current and former fellows have as to which characteristics lead to successful match in an HPB fellowship, concordant with what program directors believe to be important in a fellowship applicant.

Program directors placed the most importance on the strength of a fellow's interview, CV, and letters of recommendation. While these results are not surprising, it does emphasize that even the most fundamental aspects of the application cannot be taken lightly. Perhaps more interesting are the characteristics viewed by program directors as less impactful on an applicant's success. For instance, average ABSITE percentile score and leadership positions were both near the bottom one-third in importance rating, yet surveyed fellows tended to excel in both areas (average ABSITE >75% and >90% holding leadership positions.) As these qualities are so common amongst the matching fellows, the low rating may be a reflection of the limited usefulness these qualities hold for program directors in differentiating candidates and not of their importance to becoming a successful HPB surgeon. Furthermore, an applicant's overall operative and research experience was viewed by program directors as more important than their HPB specific experiences. While this may seem counter-intuitive initially, with the majority of surgical residents seeking specialty training, it is seems reasonable that program directors would be attracted to candidates with a solid foundation as opposed to those deemed “pre-trained.”

It is well established that up to 70–80% of graduating chief surgery residents will pursue fellowship training.2, 11, 12 When viewed in the context of the current work hour restrictions, it is easy to attribute this to a lack of confidence in training on the part of the residents. A recent study by Friedell et al. showed that most graduating chief residents in fact were confident and sought advanced training out of a true interest for the field.11 Only 7% entered into fellowship training due to a lack of confidence in their training. Interestingly, aside from esophagectomy, the residents in this study were most uncomfortable performing HPB cases (open common duct exploration [27%], pancreaticoduodenectomy [38%], hepatic lobectomy [48%], esophagectomy [60%]).11

HPB surgeries can be, undoubtedly, among the most difficult and complex cases encountered by general surgeons. As these patients continue to be referred to and cared for by specialists, it is less likely that graduating residents will obtain sufficient training in managing their disease processes. Approximately 50% of graduating chief residents finish residency with less than 10 cases in each of the liver, pancreas, and biliary categories.13 When compared to recent averages for graduates of AHPBA fellowships (median 26 biliary, 19 major liver, 28 minor liver, 40 pancreaticoduodenectomy, 18 distal pancreatectomy, and 9 other pancreas cases), it is clear that general surgery residents are by and large ill-prepared to perform HPB cases without advanced training.14 Ali et al. showed that most states (28 of 46 sampled) had a lower than expected number of HPB cases according to the state's population.15 With the majority of the USA underserved in terms of HPB surgical services and the limited number of graduating chief surgery residents capable of providing that expertise, the need for fellowship trained HPB surgeons is enduring.

There are several disadvantages to web based survey designs which most commonly include sample frame and non-response bias.16 Sample frame bias most commonly occurs when social and spatial divide precludes access to the internet but the nature of our study population makes this highly unlikely.16 Non-response bias occurs when respondents within the sample frame have very different attitudes or demographics as compared to those who do respond. The effect of this bias increases when different levels of technical ability are present amongst respondents and when response rates are low.16 The sampled population is fairly homogenous and we would not expect highly discordant attitudes from non-responders. The majority of fellow responders were current fellows at the time of their participation in the study and the rest graduated within the last five years. Our ability to survey fellows further out from training was limited by the availability of current contact information. Although this could introduce some degree of bias because the data is heavily weighted towards more contemporary fellows, the authors feel it allowed the results to more accurately represent the most current conditions applicants will encounter as they seek HPB fellowship training. Despite the fact that this survey was performed in a blinded fashion, survey respondents are still prone to the Hawthorne effect whereby respondents' answers may be subconsciously altered due to the fact that they are aware the responses will be reviewed by the investigators.

There was some difficulty in interpreting some of the results of the program directors survey. This can be inherent to this type of study to some degree but is also a by-product of an inadequacy of survey question design. For instance, when asked regarding the degree of importance placed on where a fellow completed surgery residency, 61.9% indicated that the type of surgical residency completed was ‘very to extremely important’, however, we do not know and can only presume which type of residency is deemed to be the best. For instance, do program directors feel an academic surgery residency is better than a hybrid or community program, or does coming from a prestigious institution carry more importance than the type of program itself? Future efforts could attempt to better clarify these questions.

This study is the first to attempt to define the qualities and characteristics of successfully matched HPB surgical fellows. If current trends in surgical training continue, it can be safely assumed that these fellowships will only become more and more competitive. The authors are hopeful this study will allow future applicants to be better informed and equipped to secure these difficult to obtain positions.

Conclusions

This study offers unique insight for candidates wishing to apply for HPB fellowship programs. The data help characterize the qualities required of a successful fellow from two perspectives: that of the program directors choosing candidates for their programs and recent, successfully matched fellow applicants. Both fellows and program directors believe interpersonal skills and perceived operative skills to be the most important in terms of an applicant's ability to successfully match. This information may serve as a guide for candidates considering applying for an HPB fellowship or currently entering the interview and match process.

Funding sources

None.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Footnotes

This study was presented at the Annual Meeting of the AHPBA, 11–15 March 2015, Miami, Florida.

References

- 1.HPB Training through the Fellowship Council/AHPBA Pathway. March 2015. http://www.ahpba.org/assets/documents/2014_fellowships.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borman K.R., Vick L.R., Biester T.W., Mitchell M.E. Changing demographics of residents choosing fellowships: longterm data from the American Board of Surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206 doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.012. 782–8; discussion 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fellowship Council – Match Statistics. March 2015. https://fellowshipcouncil.org/fellowship-programs/match-statistics Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraser J.D., Aguayo P., St Peter S., Ostlie D.J., Holcomb G.W., 3rd, Andrews W.A. Analysis of the pediatric surgery match: factors predicting outcome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:1239–1244. doi: 10.1007/s00383-011-2912-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulaylat A.N., Kenning E.M., Chesnut C.H., 3rd, James B.C., Schubart J.R., Saunders B.D. The profile of successful applicants for endocrine surgery fellowships: results of a national survey. Am J Surg. 2014;208:685–689. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golnik A., Ireland M., Borowsky I.W. Medical homes for children with autism: a physician survey. Pediatrics. 2009;123:966–971. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potts H.W., Wyatt J.C. Survey of doctors' experience of patients using the Internet. J Med Internet Res. 2002;4:e5. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4.1.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dykema J., Stevenson J., Day B., Sellers S.L., Bonham V.L. Effects of incentives and prenotification on response rates and costs in a national web survey of physicians. Eval Health Prof. 2011;34:434–447. doi: 10.1177/0163278711406113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLean S.A., Feldman J.A. The impact of changes in HCFA documentation requirements on academic emergency medicine: results of a physician survey. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:880–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monkey S. 2015. Help- What is the Rating Average and How is it Calculated?http://help.surveymonkey.com/articles/en_US/kb/What-is-the-Rating-Average-and-how-is-it-calculated#part2 [cited 2015 March]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedell M.L., VanderMeer T.J., Cheatham M.L., Fuhrman G.M., Schenarts P.J., Mellinger J.D. Perceptions of graduating general surgery chief residents: are they confident in their training? J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller A.T., Swain G.W., Widmar M., Divino C.M. How important are American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination scores when applying for fellowships? J Surg Educ. 2010;67:149–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sachs T.E., Ejaz A., Weiss M., Spolverato G., Ahuja N., Makary M.A. Assessing the experience in complex hepatopancreatobiliary surgery among graduating chief residents: is the operative experience enough? Surgery. 2014;156:385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeyarajah D.R., Patel S., Osman H. The current state of hepatopancreatobiliary fellowship experience in North America. J Surg Educ. 2015;72:144–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali N., O'Rourke C., El-Hayek K., Chalikonda S., Jeyarajah D.R., Walsh R.M. Estimating the need for hepato-pancreatico-biliary surgeons in the USA. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:352–356. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming C.M., Bowden M. Web-based surveys as an alternative to traditional mail methods. J Environ Manag. 2009;90:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]