Abstract

Background

ALPPS was developed to induce accelerated future liver remnant (FLR) hypertrophy in order to increase hepatic tumour resectability and reduce the risk of post-operative liver failure. While early studies demonstrated concerning complication rates, others reported favourable results. This inconsistency may be due to variability in surgical indications and technique.

Methods

A web-based survey was sent to surgeons participating in the International ALPPS Registry in September of 2014. Questions addressed surgeon demographics and training, surgical indications and technique, and clinical management approaches.

Results

Fifty six out of 85 surgeons from 78 centers responded (66%) and half (n = 30) had training in liver transplantation. Forty seven (84%) did not reserve ALPPS solely for colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) and 30 (54%) would perform ALPPS for an FLR over 30%. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for CRLM was recommended by 37 (66%) respondents. Surgical approaches varied considerably, with 30% not preserving outflow to the middle hepatic vein and 39% believing it necessary to skeletonize the hepatoduodenal ligament. Twenty five (45%) surgeons have observed segment 4 necrosis.

Conclusion

There is considerable variability in how ALPPS is performed internationally. This heterogeneity in practice patterns may explain the current incongruity in published outcomes, and highlights the need for standardization.

Introduction

Controversial since its first description in 2012, the ALPPS procedure has demonstrated impressive accelerated liver hypertrophy and expansion of resectability for high liver tumour load, as well as unacceptably high morbidity and mortality.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Inconsistent results plague the procedure: some centers report high mortality rates5, 8 while others report no mortality.3, 4, 7, 13 The source of this inconsistency is uncertain. Our group hypothesized that variation with respect to indications for surgery, pre-operative decision making, perioperative care, and surgical technique may explain some of these inconsistencies in published outcomes. This information might be a first step in achieving an acceptable multicenter morbidity and mortality through international standardization of patient selection, indications and surgical technique.

ALPPS has been plagued by skepticism since the original landmark study was published in 2012. This study reported an unacceptably high 90-day mortality of 12%,1 and subsequent reports also confirmed this high risk.2, 5, 6, 8, 14 Individual centers have reported mortality rates up to 22% and 29%.5, 8 ALPPS has also been associated with a high rate of severe complications (Clavien-Dindo classification over IIIB), with some series reporting up to 28%.6 The first analysis of the international registry reported that the rate of post-operative liver failure by 50-50 criteria is 9% after either the first or second stage of ALPPS.6 This has led to calls for caution from experienced liver centers15, 16 and controversial discussions at recent hepatobiliary meetings.

Not all ALPPS outcomes have been so problematic. In fact, several studies have demonstrated impressive hypertrophy with a 60–90% increase in volume between stages 1 and 2, with almost all patients going on to complete the second stage with an R0 resection.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Furthermore, some centers have reported no mortalities and low morbidity in their series.3, 4, 7, 13

Two explanations for this variability in reported ALPPS outcomes among centers have been suggested. The first explanation is variability in surgical indications, which was suggested by an analysis of the international registry report to play a major role in determining outcomes.6 For instance, the use of ALPPS for primary liver tumours was associated with high morbidity and mortality, especially in elderly patients; similarly, a prolonged stage 1 with operating time over 5 h, combined with blood transfusions, yielded inferior outcomes.6 The second explanation for variable ALPPS outcomes is the abundance of technical variations on the original ALPPS technique. Developed in an attempt to improve outcomes, these include the non-touch anterior approach,17, 18, 19 the “hybrid ALPPS” which combines parenchymal transection with portal vein embolization,20 the use of a liver tourniquet rather than an in-situ split of liver parenchyma,10 radio-frequency assisted liver partition (RALPP),21 laparoscopic ALPPS,22, 23, 24 as well as a myriad of modifications regarding which segments of the liver are resected and preserved.25, 26, 27

While ALPPS outcomes have garnered much controversy, variability in surgical indications and technical procedures have received insufficient attention. Before rejecting ALPPS as unsafe, these explanations require systematic study. Towards this end, a voluntary survey was conducted of surgeons collaborating in the international ALPPS registry to explore their approaches to surgical indications and surgical technique.

Methods

The survey instrument was created by consensus amongst experts in the ALPPS procedure. An initial draft was pilot tested with additional experts and modified based on feedback. The study protocol and survey questions were approved by the Scientific Committee of the International ALPPS Registry. The final survey instrument contained 47 questions designed to evaluate current practice patterns among surgeons performing the ALPPS procedure internationally. It was divided into five thematic sections consisting of questions addressing: demographics and training of respondents, indications for ALPPS, surgical technique of stage 1, clinical management during the interval between stages 1 and 2, and surgical technique of stage 2.

Specific questions pertained to patient factors, tumour characteristics, indications for ALPPS, and the use of systemic chemotherapy. Further questions sought out surgeons' opinions regarding the use of intraoperative ultrasound, parenchymal transection, approach to the hepatoduodenal ligament, and approach to ligation of the right portal vein during stage 1, as well as the right hepatic artery and bile duct in stage 2. Additional questions were posed regarding perioperative care such as post-operative nutrition, use of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis, diagnosis and treatment of post-hepatectomy liver failure, as well as specific complications.

E-mail invitations for participation in the survey as well as a link to the web-based survey (QuestionPro, 2014) were sent to all attending HPB surgeons from centers that are members of the ALPPS registry (Appendix 1 and 2). The International ALPPS Registry was initiated in 2012 and included over 500 patients from 78 centers in 48 countries in March 2015. The invitation e-mail stipulated that participation in the survey was voluntary and anonymous with no financial incentive, and consent was inferred with participation. Using a modified Dillman approach,28 after the initial email invitation in September of 2014, potential participants received three additional weekly reminders with a defined end date for participation in the survey in October of 2014. Opening the e-mail and viewing the survey was considered as receiving the invitation for purposes of response rate calculation. Each participant was assigned a unique coded identification number by the web-based software to determine survey completion without linkage to identifying data, and all survey responses remained de-identified for analysis.

Data are presented primarily as frequencies with associated percentages. Categorical responses were compared using chi-square or Fischer's exact tests where appropriate. All data were analyzed using SPSS Version 20 (Chicago, Ill), with a p-value of <0.05 considered significant.

Results

Demographics, training, clinical practice, and experience of participants

Eighty-five attending surgeons with an independent practice from 78 international centers were individually addressed by e-mail. Fifty-six attending surgeons completed the survey (response rate 66%). The majority of the respondents (n = 36, 64%) were from Europe with fewer surgeons from North America (n = 4, 7%), South America (n = 5, 9%), and Asia (n = 9, 16%). Approximately half of the respondents (n = 30, 54%) had training in liver transplantation. The majority of surgeons surveyed (n = 34, 61%) did not perform liver transplantation in their current practice. The majority of respondents (n = 50, 89%) had performed 12 or less ALPPS procedures, and 24 surgeons (43%) reported performing ALPPS for 1 year or less at the time of survey completion.

Indications for ALPPS

Age and performance status

Most respondents (n = 41, 73%) consider patient age in their pre-operative decision making and patient selection, but only 2 out of 56 surgeons (4%) stated that they had a firm age cut-off, beyond which they would not consider performing ALPPS. For most (n = 46, 82%) respondents, patients considered for ALPPS have to be at minimum ambulatory. No respondents reported that they would consider ALPPS for patients who are confined to bed or chair more than 50% of the time (ECOG 3 and 4).

FLR volume

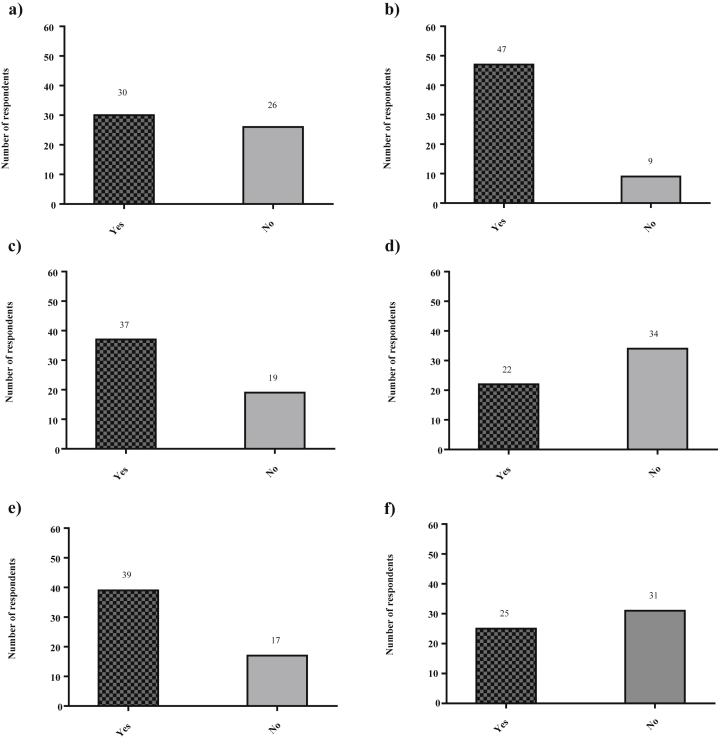

Thirty surgeons (54%) would consider performing an ALPPS for an FLR predicted by volumetry to be greater than 30% (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

a) Would you ever consider performing an ALPPS procedure in a case where the future liver remnant (FLR) is over 30%?. b) Would you perform the ALPPS procedure for indications other than colorectal liver metastases (CRLM)?. c) Do you routinely recommend that your patients receive systemic neoadjuvant chemotherapy treatment for colorectal liver metastases prior to ALPPS?. d) Do you feel that it is necessary to skeletonize the structures of the hepatoduodenal ligament in the ALPPS procedure?. e) Do you routinely preserve outflow to the middle hepatic vein during stage 1 of a classical ALPPS?. f) Have you observed necrosis of segment 4 at stage 2 of the ALPPS procedure?

Tumour types and liver parenchyma

The majority of surgeons (n = 47, 84%) would consider performing ALPPS for indications other than colorectal liver metastases (CRLM), with only 9 (16%) reserving ALPPS solely for CRLM (Fig. 1b). Twenty surgeons (36%) and 15 surgeons (27%) respectively would consider performing ALPPS for hilar cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder cancer. In addition, 53 surgeons (95%) answered that Child Pugh Class B cirrhosis is an absolute contraindication to ALPPS, while only ten (18%) consider Child Pugh Class A cirrhosis to be an absolute contraindication.

Chemotherapy

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is routinely recommended by 37 respondents (66%) prior to performing the ALPPS procedure in patients with CRLM (Fig. 1c). With respect to tumour response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the majority of surgeons reported that they require no tumour progression during chemotherapy treatment (n = 35, 63%) or a partial response of the tumour to treatment (n = 7, 13%) to perform an ALPPS procedure. However, 14 respondents (25%) indicated that they would still consider performing ALPPS even in the context of tumour progression during neoadjuvant chemotherapy as long as the tumours are resectable via ALPPS.

Technique preferences by surgeons

Over two thirds of respondents (n = 38, 68%) indicated that they had already performed an anatomical modification of the ALPPS procedure involving the preservation of segments other than segments 2 and 3. Moreover, 20 respondents (36%) had performed a technical modification of the ALPPS procedure. Specifically two surgeons had performed Radio-frequency Assisted Liver Partition with Portal Vein Ligation (RALPP), two had performed Associating Liver Tourniquet and Portal ligation for Staged hepatectomy (ALTPS), three had performed Hybrid ALPPS (parenchymal transection in stage 1 of ALPPS plus portal vein embolization), and 15 had reported partial ALPPS (only partial transection of the liver parenchyma during stage 1 of ALPPS). Forty-three respondents (77%) completely partition the liver until they visualize the inferior vena cava in stage 1 of ALPPS. With respect to the “anterior approach”, thirteen respondents (23%) indicated that they routinely use it during ALPPS procedures. Thirty surgeons (54%) routinely use the hanging maneuver and almost all surgeons (n = 53, 95%) use intraoperative ultrasound during their ALPPS procedures.

Sixteen survey respondents (29%) reported routinely performing a lymphadenectomy of the hepatoduodenal ligament, irrespective of diagnosis. Twenty two surgeons (39%) believed it necessary to skeletonize the structures within the hepatoduodenal ligament (Fig. 1d). Thirty-nine surgeons (70%) preserve the outflow to the middle hepatic vein during stage 1 of ALPPS, while 17 (30%) do not (Fig. 1e). In addition, the majority (n = 38, 68%) also make use of intermittent hepatic inflow occlusion (eg. Pringle maneuver) during the first stage of the ALPPS procedure, while 18 (32%) rarely or never use it. Twenty-seven surgeons (48%) use inflow occlusion in the situation of bleeding. Barrier devices between the two portions of the liver are used by 34 surgeons (61%), with the plastic bag still being the most popular barrier device. Of all surgeons surveyed, 25 (45%) have observed some evidence of necrosis of Segment 4 of the liver during the second stage of ALPPS (Fig. 1f).

Comparison of responses based on geographic, demographic, and operative factors

Surgeons who reported that they would consider performing ALPPS for an FLR of over 30% were more likely to also perform ALPPS for non-CRLM (97% vs. 69%, p = 0.008). They were also more likely to perform an anatomical variation of ALPPS (80% vs. 54%, p = 0.048).

Geographic location (ie. Europe, North America, South America, or Asia) did not increase the likelihood of performing ALPPS for non-colorectal liver metastases, performing anatomical variations of ALPPS, or the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Table 1). Surgeon experience (number of ALPPS procedures performed) did not correlate with performing ALPPS for non-CRLM, performing an anatomical variation of ALPPS, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or performing ALPPS for an FLR over 30% (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of responses with respect to surgeons' geographic location (ie. continent) and performing ALPPS for non-colorectal liver metastases, performing anatomical variations of ALPPS, or recommending neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to performing ALPPS for CRLM

| Europe | North America | South America | Asia and other | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALPPS for non-CRLM, n (%) | 29 (81) | 4 (100) | 3 (60) | 11 (100) | 0.06 |

| Anatomical variation of ALPPS, n (%) | 25 (69) | 2 (50) | 3 (60) | 8 (73) | 0.82 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 23 (64) | 2 (50) | 4 (80) | 8 (73) | 0.76 |

Table 2.

Comparison of responses with respect to surgeon experience (ie. number of ALPPS performed) and performing ALPPS for non-colorectal liver metastases, performing anatomical variations of ALPPS, recommending neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to performing ALPPS for CRLM, or performing ALPPS for an FLR over 30%

| 1–5 ALPPS | 6–12 ALPPS | 13 or More ALPPS | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALPPS for non-CRLM, n (%) | 22 (79) | 19 (86) | 6 (100) | 0.4 |

| Anatomical variation, n (%) | 16 (57) | 16 (73) | 6 (100) | 0.1 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 18 (64) | 14 (64) | 5 (83) | 0.64 |

| ALPPS for FLR >30%, n (%) | 12 (43) | 13 (59) | 5 (83) | 0.16 |

Discussion

This study looked at how the ALPPS procedure is actually being performed by directly surveying those surgeons performing the procedure and participating in an international register. Ultimately, there was a lack of consensus among respondents regarding their approach to the management of patients undergoing ALPPS and considerable variability in the way the procedure is performed. While Kokudo et al. and others29, 30, 31 have highlighted the importance of standardizing ALPPS to improve its safety, this study indicates that there is currently no international standardization. Furthermore, there is little agreement among ALPPS surgeons on how the procedure should be performed and on whom it should be performed.

Contrary to the popular belief that ALPPS is being performed mainly by liver transplant surgeons, a large proportion of survey respondents who are performing ALPPS have no liver transplant training. Furthermore, although approximately half of ALPPS surgeons do have liver transplant training, they are not all actually performing liver transplantation in their current practice. The survey also emphasizes that the experience of most surgeons currently performing ALPPS is limited in terms of numbers of procedures performed as well as the length of time they have been performing them. The majority of ALPPS surgeons appear to be practicing in Europe, with only a minority of respondents practicing in North America, South America, or Asia.

This study also found that there is widespread disagreement among ALPPS surgeons regarding indications – particularly with respect to tumour types. The first report of the international registry demonstrated that ALPPS had a dramatically increased complication rate when performed for primary liver and bile duct tumours.6 Others have reported a higher morbidity and mortality with ALPPS that requires biliary reconstruction, and when ALPPS is performed for cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder cancer.1, 5, 8 Despite these reports of increased morbidity and mortality in ALPPS procedures performed for non-CRLM,6 as well as decreased morbidity and mortality in ALPPS procedures reserved solely for CRLM,4 a significant majority of surgeons surveyed would still consider performing ALPPS for non-CRLM. With respect to indications for the ALPPS procedure, surgeons' practice patterns are therefore not congruent with the available published evidence.

Although a published indication for the ALPPS procedure is an FLR of less than 30%, over half of the surveyed surgeons reported that they would perform ALPPS even in the setting of an FLR over 30%. ALPPS literature recommends that the procedure ought to be reserved only for patients whose FLR is inadequate, and the reported preoperative FLR is between 0.19 and 0.27.2, 4, 5, 6 When comparing surgeon experience to likelihood of considering ALPPS for an FLR over 30%, there was a general trend towards surgeons who have performed more ALPPS procedures being more likely to operate for an FLR over 30%. This may suggest increased confidence to experiment with the ALPPS concept in scenarios outside of the classically proposed indications. Our survey did not evaluate whether the respondents' centers have adequate access to, or experience with, PVE. Insufficient PVE capability could potentially explain why ALPPS is being performed at some centers, and this has been suggested in a recent study.32

Similarly, despite published reports of 80–100% of patients with CRLM receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy,5 34% of ALPPS surgeons surveyed did not routinely recommend neoadjuvant chemotherapy for CRLM. Furthermore, a quarter of the surgeons surveyed would operate even in the context of tumour progression after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, despite published evidence to the contrary.33 Response to pre-operative chemotherapy has been considered a marker of favourable tumour biology,4, 33 while progression on chemotherapy may be indicative of early recurrence and poor prognosis following ALPPS or any other surgical therapy. Surgeons performing ALPPS should comply with multidisciplinary treatment algorithms.

In addition to the disagreement about indications and the disregard for established practice in surgical oncology, we also found disagreement with respect to surgical technique utilized by ALPPS surgeons. In spite of reporting limited experience with the procedure, the majority of responding surgeons have already performed a modification on the classic right trisectionectomy ALPPS. A substantial proportion has also performed a technical modification such as RALPP, ALTPS, Hybrid ALPPS, partial ALPPS, as well as the anterior approach. This suggests that ALPPS surgeons are willing to experiment with ALPPS and look for new modifications on the classically described procedure, even when they have limited experience with conventional ALPPS technique. These modifications may arise from a willingness to improve the initial unfavorable outcomes of ALPPS and decrease the technical complexity of the original procedure, while still capitalizing on its impressive hypertrophy and ability to achieve an R0 resection.

There was little consensus overall on many technical aspects of the operation, apart from the use of intraoperative ultrasound. Surgeons did not agree on complete transection of the liver until the IVC is visualized, the need for lymphadenectomy or skeletonization of the hepatoduodenal ligament, nor was there consensus regarding the preservation of the middle hepatic vein in the deportalized liver during stage 1 of ALPPS. These differences in preferred technique may explain the segment 4 necrosis that 45% of surgeons observed, as experienced ALPPS surgeons have emphasized the importance of not completely devascularizing segment 4.34

Our study had several limitations inherent to the survey format, including recall bias. The survey assessed ALPPS surgeons' stated opinions, preferences and recollections of their practice with respect to ALPPS, but whether these are indicative of actual practice patterns is unknown. The survey's findings may also not be accurately representative of all ALPPS surgeons collaborating in the international ALPPS registry, since we do not know how non-respondents may differ from respondents. Finally, since we only surveyed surgeons who are collaborating in the ALPPS registry, our findings may not be representative of surgeons performing ALPPS and not collaborating with the registry.

This is the first comprehensive review of the attitudes and reported practices of pioneers and rapid adaptors of a highly controversial procedure in liver surgery. Our findings reflect the observations and opinions of 66% of the surgeons who submit patient data to the international ALPPS registry. With reference to indications for the ALPPS procedure, such as tumour types, FLR, the administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and technical aspects of the operation such as the approach to the hepatoduodenal ligament and middle hepatic vein, our survey results suggest that there is no international consensus on ALPPS. It appears that surgeons are effectively performing very different operations in the setting of diverse indications – and calling these procedures “ALPPS”. This heterogeneity in practice patterns may help to explain the incongruity in published results, and particularly the discrepancy in published morbidity and mortality from various groups.

Our study highlights the need for consensus recommendations regarding ALPPS to achieve more careful patient selection and standardize the surgical technique in order to bring the current morbidity and mortality to acceptable and consistent levels. Standardization of surgical practice for ALPPS is absolutely essential if this innovative procedure is to be embraced internationally, or submitted to meaningful multicenter studies to test its efficacy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Lorelei Lingard and the Centre for Education Research and Innovation (CERI) at Western University for their expertise and support in the process of writing this study for publication, as well as the international ALPPS Registry for assisting with surgeons' contact information for the web-based survey.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2016.01.547.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Schnitzbauer A.A., Lang S.A., Goessmann H., Nadalin S., Baumgart J., Farkas S.A. Right portal vein ligation combined with in situ splitting induces rapid left lateral liver lobe hypertrophy enabling 2-staged extended right hepatic resection in small-for-size settings. Ann Surg. 2012 Mar;255:405–414. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824856f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schadde E., Ardiles V., Slankamenac K., Tschuor C., Sergeant G., Amacker N. ALPPS offers a better chance of complete resection in patients with primarily unresectable liver tumors compared with conventional-staged hepatectomies: results of a multicenter analysis. World J Surg. 2014 Apr 19;38:1510–1519. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2513-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sala S., Ardiles V., Ulla M., Alvarez F., Pekolj J., de Santibañes E. Our initial experience with ALPPS technique: encouraging results. Updates Surg. 2012 Aug 18;64:167–172. doi: 10.1007/s13304-012-0175-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandez-Alejandro R., Bertens K.A., Pineda-Solis K., Croome K.P. Can we improve the morbidity and mortality associated with the associating liver partition with portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) procedure in the management of colorectal liver metastases? Surgery. 2015 Feb;157:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nadalin S., Capobianco I., Li J., Girotti P., Königsrainer I., Königsrainer A. Indications and limits for associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS). Lessons learned from 15 cases at a single centre. Z Gastroenterol. 2014 Jan;52:35–42. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1356364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schadde E., Ardiles V., Robles-Campos R., Malago M., Machado M., Hernandez-Alejandro R. Early survival and safety of ALPPS: first report of the International ALPPS Registry. Ann Surg. 2014 Nov;260:829–838. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvarez F.A., Ardiles V., Claria R.S., Pekolj J., de Santibañes E. Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy (ALPPS): tips and tricks. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012 Nov 27;17:814–821. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-2092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J., Girotti P., Königsrainer I., Ladurner R., Königsrainer A., Nadalin S. ALPPS in right trisectionectomy: a safe procedure to avoid postoperative liver failure? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013 Jan 4;17:956–961. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-2132-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knoefel W.T., Gabor I., Rehders A., Alexander A., Krausch M., Schulte am Esch J. In situ liver transection with portal vein ligation for rapid growth of the future liver remnant in two-stage liver resection. Br J Surg. 2013 Feb;100:388–394. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robles R., Parrilla P., López-Conesa A., Brusadin R., de la Peña J., Fuster M. Tourniquet modification of the associating liver partition and portal ligation for staged hepatectomy procedure. Br J Surg. 2014 Aug;101:1129–1134. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9547. discussion 1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ratti F., Cipriani F., Gagliano A., Catena M., Paganelli M., Aldrighetti L. Defining indications to ALPPS procedure: technical aspects and open issues. Updates Surg. 2013 Dec 17;66:41–49. doi: 10.1007/s13304-013-0243-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres O.J.M., Fernandes E. de SM., Oliveira C.V.C., Lima C.X., Waechter F.L., Moraes-Junior J.M.A. Ligadura da veia porta associada à bipartição do fígado para hepatectomia em dois estágios (ALPPS): experiência brasileira. ABCD Arq Bras Cir Dig (São Paulo) 2013 Mar;26:40–43. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oldhafer K.J., Donati M., Jenner R.M., Stang A., Stavrou G.A. ALPPS for patients with colorectal liver metastases: effective liver hypertrophy, but early tumor recurrence. World J Surg. 2013 Dec 11;38:1504–1509. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schadde E., Raptis D., Schnitzbauer A.A., Ardiles V., Tschuor C., Lesurtel M. Prediction of mortality after ALLPS stage-1-an analysis of 320 patients from the International ALPPS Registry. Ann Surg. 2015 Nov;262:780–785. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figueras J., Belghiti J. The ALPPS approach: should we sacrifice basic therapeutic rules in the name of innovation? World J Surg. 2014 Apr 23;38:1520–1521. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2540-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aloia T.A., Vauthey J.-N. Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy (ALPPS): what is gained and what is lost? Ann Surg. 2012 Sep;256:e9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318265fd3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ardiles V., Schadde E., Santibanes E., Clavien P.A. Commentary on “Happy marriage or ”dangerous liaison“: ALPPS and the anterior approach”. Ann Surg. 2014 Aug;260:e4. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vennarecci G., Levi Sandri G.B., Ettorre G.M. Performing the ALPPS procedure by anterior approach and liver hanging maneuver. Ann Surg. 2016 Jan;263:e11. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan A.C.Y., Pang R., Poon R.T.P. Simplifying the ALPPS procedure by the anterior approach. Ann Surg. 2014 Aug;260:e3. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J., Kantas A., Ittrich H., Koops A., Achilles E.G., Fischer L. Avoid “All-Touch” by hybrid ALPPS to achieve oncological efficacy. Ann Surg. 2016 Jan;263:e6–e7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gall T.M.H., Sodergren M.H., Frampton A.E., Fan R., Spalding D.R., Habib N.A. Radio-frequency-assisted Liver Partition with Portal vein ligation (RALPP) for liver regeneration. Ann Surg. 2015 Feb;261:e45–e46. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machado M.A.C., Makdissi F.F., Surjan R.C. Totally laparoscopic ALPPS is feasible and may be worthwhile. Ann Surg. 2012 Sep;256:e13. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318265ff2e. author reply e16–e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conrad C., Shivathirthan N., Camerlo A., Strauss C., Gayet B. Laparoscopic portal vein ligation with in situ liver split for failed portal vein embolization. Ann Surg. 2012 Sep;256:e14–e25. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318265ff44. author reply e16–e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai X., Peng S., Duan L., Wang Y., Yu H., Li Z. Completely laparoscopic ALPPS using round-the-liver ligation to replace parenchymal transection for a patient with multiple right liver cancers complicated with liver cirrhosis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2014 Nov 11;24:883–886. doi: 10.1089/lap.2014.0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selby K., Hernandez-Alejandro R. Two-stage hepatectomy for liver metastasis from colorectal cancer. CMAJ. 2014 Oct 21;186:1163–1166. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gauzolino R., Castagnet M., Blanleuil M.L., Richer J.P. The ALPPS technique for bilateral colorectal metastases: three “variations on a theme”. Updates Surg. 2013 May 21;65:141–148. doi: 10.1007/s13304-013-0214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Santibañes M., Alvarez F.A., Santos F.R., Ardiles V., de Santibañes E. The associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy approach using only segments I and IV as future liver remnant. J Am Coll Surg. 2014 Aug;219:e5–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dillman D.A., Phelps G., Tortora R., Swift K., Kohrell J., Berck J. Response rate and measurement differences in mixed-mode surveys using mail, telephone, interactive voice response (IVR) and the Internet. Soc Sci Res. 2009 Mar;38:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kokudo N., Shindoh J. How can we safely climb the ALPPS? Updates Surg. 2013 May 29;65:175–177. doi: 10.1007/s13304-013-0215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schadde E., Schnitzbauer A.A., Tschuor C., Raptis D.A., Bechstein W.O., Clavien P.-A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of feasibility, safety, and efficacy of a novel procedure: associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015 Sept;22:3109–3120. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertens K.A., Hawel J., Lung K., Buac S., Pineda-Solis K., Hernandez-Alejandro R. ALPPS: challenging the concept of unresectability – a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2015 Jan;13:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Day R.W., Conrad C., Vauthey J.-N., Aloia T.A. Evaluating surgeon attitudes towards the safety and efficacy of portal vein occlusion and associating liver partition and portal vein ligation: a report of the MALINSA survey. HPB. 2015 Oct;17:936–941. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giuliante F., Ardito F., Ferrero A., Aldrighetti L., Ercolani G., Grande G. Tumor progression during preoperative chemotherapy predicts failure to complete 2-stage hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases: results of an Italian multicenter analysis of 130 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2014 Aug;219:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez F.A., Ardiles V., de Santibañes M., Pekolj J., de Santibañes E. Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy offers high oncological feasibility with adequate patient safety: a prospective study at a single center. Ann Surg. 2014 Dec:1. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.