Two new precursors to sustained NO-releasing materials have been characterized. The structures are compared with reported analogues, revealing significant differences in molecular conformation, intermolecular interactions, and packing that result from modest changes in functional groups. The structures are also discussed in terms of potential NO-release capability.

Keywords: nitric oxide, sustained NO-releasing materials, aniline, l-phenylalanine, crystal structure

Abstract

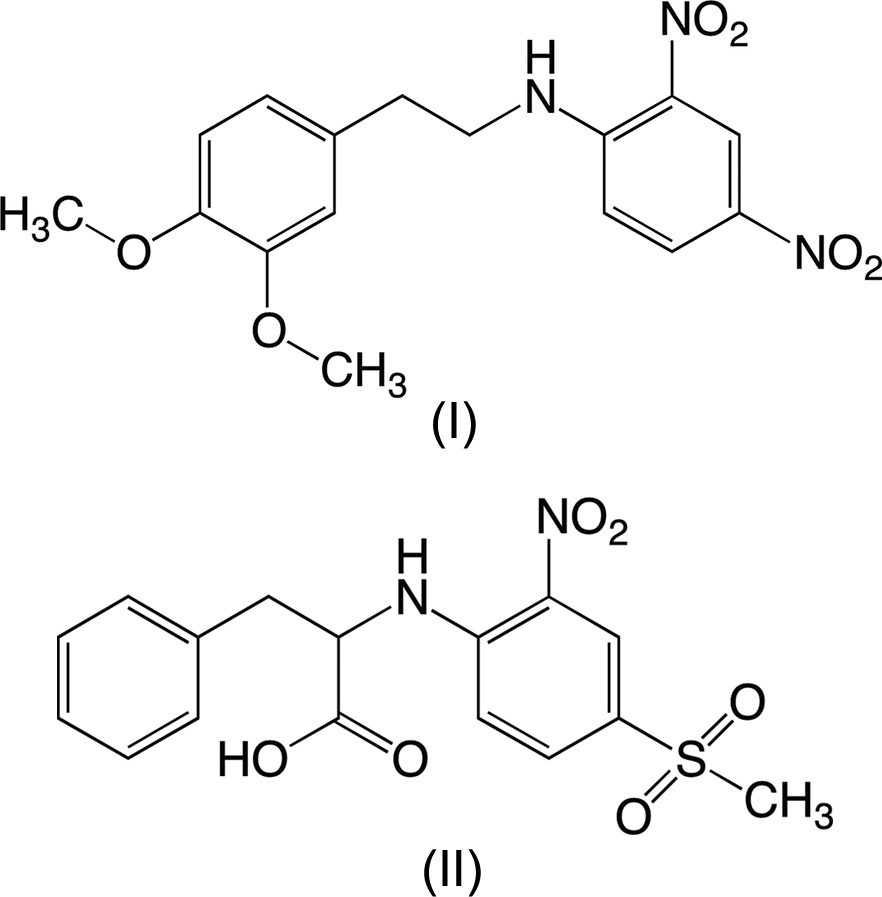

Notwithstanding its simple structure, the chemistry of nitric oxide (NO) is complex. As a radical, NO is highly reactive. NO also has profound effects on the cardiovascular system. In order to regulate NO levels, direct therapeutic interventions include the development of numerous NO donors. Most of these donors release NO in a single high-concentration burst, which is deleterious. N-Nitrosated secondary amines release NO in a slow, sustained, and rate-tunable manner. Two new precursors to sustained NO-releasing materials have been characterized. N-[2-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)ethyl]-2,4-dinitroaniline, C16H17N3O6, (I), crystallizes with one independent molecule in the asymmetric unit. The adjacent amine and nitro groups form an intramolecular N—H⋯O hydrogen bond. The anti conformation about the phenylethyl-to-aniline C—N bond leads to the planes of the arene and aniline rings being approximately perpendicular. Molecules are linked into dimers by weak intermolecular N—H⋯O hydrogen bonds such that each amine H atom participates in a three-center interaction with two nitro O atoms. The dimers pack so that the arene rings of adjacent molecules are not parallel and π–π interactions do not appear to be favored. N-(4-Methylsulfonyl-2-nitrophenyl)-l-phenylalanine, C16H16N2O6S, (II), with an optically active center, also crystallizes with one unique molecule in the asymmetric unit. The l enantiomer was established via the configuration of the starting material and was confirmed by refinement of the Flack parameter. As in (I), there is an intramolecular N—H⋯O hydrogen bond between adjacent amine and nitro groups. The conformation of the molecule is such that the arene rings display a dihedral angle of ca 60°. Unlike (I), molecules are not linked via intermolecular N—H⋯O hydrogen bonds. Rather, the carboxylic acid H atom forms a classic, approximately linear, O—H⋯O hydrogen bond with a sulfone O atom. Pairs of molecules related by twofold rotation axes are linked into dimers by two such interactions. The packing pattern features a zigzag arrangement of the arene rings without apparent π–π interactions. These structures are compared with reported analogues, revealing significant differences in molecular conformation, intermolecular interactions, and packing that result from modest changes in functional groups. The structures are discussed in terms of potential NO-release capability.

Introduction

Nitrogen monoxide, commonly known as nitric oxide (NO), is produced in vivo from l-arginine (Miller & Megson, 2007 ▸). The conversion of l-arginine to NO and citrulline is catalyzed by nitric oxide synthases along with a series of cofactors. Notwithstanding its simple structure, the chemistry of NO is complex. As a radical, NO is highly reactive and it is consumed quickly within a radius of 100 µm. Therefore NO, which has profound effects on the cardiovascular system, must be produced slowly in small fluxes at the inner walls of blood vessels by endothelial cells (Zhou et al., 2006 ▸).

Since the discovery of the vaso-relaxing effects of NO (Cauwels, 2007 ▸), its physiological impact on the cardiovascular system has been the most studied. Endothelial cells, which line the lumen of the blood vessels, produce NO from l-arginine. The conversion is catalyzed by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). The lypophilicity, small size, and chemical lability of NO allows for easy passage through cell membranes, without the use of channels or receptors, to neighboring cells (Miller et al., 2004 ▸). The effects of NO on the underlying vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) include vasodilation and inhibition of VSMC proliferation, as well as its migration to the endothelial layer (Jeremy et al., 1999 ▸).

The salutary roles of NO in the functioning of the cardiovascular, nervous, respiratory, and immune systems, in addition to its protecting functions of the heart, brain, and kidneys, have been well documented (Jobgen et al., 2006 ▸). On the other hand, high NO concentrations cause apoptosis and other complications, including septic and hemorrhagic shock, multiple sclerosis, neurodegenerative diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and cancer (Jeremy et al., 1999 ▸; Lundberg et al., 2015 ▸). A wide variety of diseases and disorders have been ascribed to NO malfunctions. These maladies include endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, asthma, pulmonary hypertension, erectile dysfunction, pre-eclampsia, and insulin resistance (Giles, 2006 ▸). The overall effects on the cardiovascular system can lead to further endothelial injury and atherosclerosis (Stasch et al., 2011 ▸).

In order to better regulate NO levels, several recommendations have been made, which include a polyphenol-rich diet (Anter et al., 2004 ▸), moderate alcohol consumption (Lucas et al., 2005 ▸), and regular exercise (Hambrecht et al., 2003 ▸). Direct therapeutic interventions include the development of numerous NO donors. Most of these donors release NO in a single high-concentration burst, which is deleterious (Cai et al., 2005 ▸). We have reported a series of N-nitrosated secondary amines that release NO in a slow, sustained, and rate-tunable manner (Wang et al., 2009 ▸; Yu et al., 2011 ▸; Curtis et al., 2013 ▸, 2014 ▸; Lagoda et al., 2014 ▸). Furthermore, the released NO has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of human aortic smooth muscle cells, a contributing factor to the progression of atherosclerosis (Yu et al., 2011 ▸; Curtis et al., 2013 ▸).

We report herein the syntheses and X-ray crystal structures of two secondary amines, the precursors to NO donors. These secondary amines, namely N-[2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)ethyl]-2,4-dinitroaniline, (I), and N-(4-methylsulfonyl-2-nitrophenyl)-l-phenylalanine, (II), differ in their hydrophilic and lipophilic balances (HLBs). We hypothesize that the HLB of an NO donor will play a crucial role in the overall NO release rates of these compounds in an aqueous medium (phosphate-buffered saline solution). Compound (I) was prepared by the reaction of 3,4-dimethoxyphenethylamine and an activated aromatic monofluoride, i.e. 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene. The synthesis of (II) was accomplished by the reaction of l-phenylalanine with 4-methylsulfonyl-2-nitrofluorobenzene.

Experimental

Synthesis and crystallization

For the synthesis of (I), sodium bicarbonate (0.373 g, 4.44 mmol), 3,4-dimethoxyphenethylamine (97%) (0.539 g, 2.88 mmol), and 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene (0.536 g, 2.88 mmol) were weighed separately in glass vials and transferred to a 50 ml round-bottomed flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar. The vials were rinsed with N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAC, 10 ml) and the rinses transferred to the reaction vessel. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 1 h, after which time the mixture was poured onto a saturated sodium chloride solution (100 ml) to precipitate the crude product. The crude product was extracted with dichloromethane (75 ml) and washed twice with deionized water (100 ml). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, followed by gravity filtration. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator. The crude product, an orange solid, was recrystallized from a dichloromethane–diethyl ether solution (1:1 v/v) as crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction (yield 55%; m.p. 379–380 K). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.10 (d, 1H), 8.57 (s, 1H), 8.24 (m, 1H), 6.84 (m, 4H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.64 (q, 2H), 3.02 (t, 2H); 13C NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 149.29, 148.13, 148.12, 136.01, 130.29, 129.66, 124.54, 120.71, 113.85, 111.68, 111.57, 55.88, 45.10, 34.50; IR (NaCl, ν, cm−1): 3357, 3107, 2934, 1621, 1590, 1517, 1465, 1423, 1335, 1305, 1263, 1238, 1196, 1144, 1084, 1027; MS (m/z) (% base peak): 347 (8), 281 (5), 207 (18), 166 (22), 151 (100), 137 (8), 107 (11), 77 (16).

Compound (II) was prepared by dissolving 4-methylsulfonyl-2-nitrofluorobenzene (0.565 g, 2.58 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (THF, 15 ml) in a 100 ml round-bottomed flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar in the presence of sodium bicarbonate (2.185 g, 24.6 mmol). The reaction mixture turned yellow upon the addition of sodium bicarbonate. l-Phenylalanine (0.406 g, 2.46 mmol) was dissolved in deionized water (25 ml) in a 50 ml beaker and the solution was subsequently transferred into the reaction vessel using a funnel. Water (5 ml) was used to wash the funnel. The reaction vessel was fitted with an air condenser and the mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 12 h, after which time the THF was removed under reduced pressure using a rotatory evaporator. The resulting aqueous solution was washed with diethyl ether (50 ml) to remove excess starting material. The crude product was precipitated via acidification of the aqueous solution (pH ca 2) using 12 M hydrochloric acid. The precipitated crude product was extracted using ethyl acetate (50 ml), which was collected and washed with deionized water (50 ml) three times. The organic layer containing the crude product was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, followed by gravity filtration. The solvent was removed using a rotary evaporator to yield a bright yellow solid. Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained by recrystallization from a dichloromethane–hexane solution (4:1 v/v) (yield 58%; m.p. 443–445 K). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ 8.58 (d, 1H), 8.50 (d, 1H), 7.92 (dd, 1H), 7.27–7.15 (overlapping peaks, 6H), 4.94 (q, 1H), 3.24 (d, 2H), 3.20 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ 172.25, 146.61, 136.40, 134.13, 130.82, 129.84, 128.83, 127.75, 127.40, 127.35, 116.67, 56.33, 44.09, 37.04; IR (solid, ν, cm−1): 3379, 3176, 3090, 1733, 1611, 1518, 1367, 1299, 1145; ESI–MS (m/z) calculated for C16H16N2O6S [M − H]− 363.38, found 363.03.

Refinement

Crystal data, data collection and structure refinement details are summarized in Table 1 ▸. H atoms on C atoms were included in calculated positions as riding atoms, with C—H bond lengths of 0.95 (aryl), 0.98 (methyl), 0.99 (methylene) and 1.00 Å (methine). H atoms on N and O atoms were located from difference Fourier syntheses and were refined isotropically without any restraints (see the N—H and O—H distances in Tables 2 ▸ and 3 ▸). For (II), the Flack x parameter was determined (Table 1 ▸), and the probability P2 = 1.000, G = 0.97 (8), and a Hooft y parameter of 0.02 (3) were determined from an analysis of the Bijvoet differences (Hooft et al., 2008 ▸). We acknowledge that the crystal of (II) was longer than optimal, but the needles were difficult to cut cleanly and the refinement results do not appear to have been adversely affected.

Table 1. Experimental details.

| (I) | (II) | |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal data | ||

| Chemical formula | C16H17N3O6 | C16H16N2O6S |

| M r | 347.33 | 364.38 |

| Crystal system, space group | Monoclinic, P21/c | Monoclinic, C2 |

| Temperature (K) | 173 | 173 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 13.0087 (12), 7.2092 (6), 17.0024 (16) | 21.260 (3), 5.7264 (6), 14.2762 (16) |

| β (°) | 101.297 (7) | 103.456 (7) |

| V (Å3) | 1563.6 (3) | 1690.3 (4) |

| Z | 4 | 4 |

| Radiation type | Mo Kα | Mo Kα |

| μ (mm−1) | 0.12 | 0.23 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.30 × 0.23 × 0.11 | 0.80 × 0.14 × 0.04 |

| Data collection | ||

| Diffractometer | Rigaku XtaLAB mini | Rigaku XtaLAB mini |

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan (REQAB; Rigaku, 1998 ▸) | Multi-scan (REQAB; Rigaku, 1998 ▸) |

| T min, T max | 0.828, 0.987 | 0.815, 0.991 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed reflections | 16236, 3578, 2913 [F 2 > 2.0σ(F 2)] | 10478, 4851, 4201 [I > 2σ(I)] |

| R int | 0.030 | 0.029 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.649 | 0.704 |

| Refinement | ||

| R[F 2 > 2σ(F 2)], wR(F 2), S | 0.039, 0.102, 1.04 | 0.039, 0.092, 1.03 |

| No. of reflections | 3578 | 4851 |

| No. of parameters | 232 | 235 |

| No. of restraints | 0 | 1 |

| H-atom treatment | H atoms treated by a mixture of independent and constrained refinement | H atoms treated by a mixture of independent and constrained refinement |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 0.25, −0.21 | 0.30, −0.29 |

| Absolute structure | – | Flack x determined using 1620 quotients [(I +) − (I −)]/[(I +) + (I −)] (Parsons et al., 2013 ▸) |

| Absolute structure parameter | – | 0.01 (4) |

Table 2. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for (I) .

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1—H1⋯O1 | 0.844 (18) | 2.029 (18) | 2.6495 (15) | 129.8 (15) |

| N1—H1⋯O1i | 0.844 (18) | 2.822 (18) | 3.644 (1) | 165.3 (15) |

Symmetry code: (i)  .

.

Table 3. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for (II) .

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O6—H61⋯O4i | 0.83 (4) | 1.90 (4) | 2.720 (3) | 168 (4) |

| N1—H1⋯O1 | 0.87 (3) | 1.98 (4) | 2.642 (3) | 132 (3) |

Symmetry code: (i)  .

.

Results and discussion

N-[2-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)ethyl]-2,4-dinitroaniline, (I), crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P21/c with one independent molecule in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 1 ▸). The adjacent amine and nitro groups form an intramolecular N—H⋯O hydrogen bond (Table 2 ▸) consistent with previous observations in molecules of this type (Wade et al., 2013 ▸; Payne et al., 2010 ▸; Gangopadhyay & Radhakrishnan, 2000 ▸; Clegg et al., 1994 ▸; Panunto et al., 1987 ▸). Aniline (I) is chemically very similar to 2,4-dinitro-N-(2-phenylethyl)aniline, (III), whose structure we reported recently (Wade et al., 2013 ▸), with (I) differing only in the presence of the methoxy groups in the 3- and 4-positions on the arene ring of the phenylethyl group. In spite of the similarity of the two molecules, there are some notable differences in their conformations. Most importantly, the dihedral angle between the planes of the two six-membered arene rings in (I) is ca 106°, while the rings in (III) are nearly parallel (dihedral angle ca 2°). This difference is attributable primarily to the C1—N1—C7—C8 torsion angle, which is 177.32 (12)° in (I) and −85.5 (2)° in (III). Other less drastic differences include rotations about the N1—C1 [C7—N1—C1—C6 torsion angle = −10.9 (2)° in (I) versus −0.9 (2)° in (III)] and C4—N3 [torsion angle O3—N3—C4—C3 = −12.6 (2)° in (I) versus −1.2 (2)° in (III)] bonds.

Figure 1.

The molecular structure of (I), showing the atom-labeling scheme and 70% probability displacement ellipsoids for the non-H atoms. The intramolecular hydrogen bond is shown as a dashed line.

As was the case in (III), neighboring molecules of (I) are related across centers of inversion so as to permit an intermolecular N—H⋯O hydrogen bond between the amine group on one molecule and the nitro group on the other molecule (Fig. 2 ▸ a). The amine H1 atom thus participates in a three-center hydrogen bond with two nitro O1 atoms, and each O1 atom serves as an acceptor for both intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonds (Table 2 ▸). The intermolecular H1⋯O1i distance of 2.822 (18) Å [symmetry code: (i) −x + 1, −y + 1, −z + 1] is significantly longer than the distance of 2.381 (19) Å observed in (III). It is also beyond the typical range for this type of amine–nitro N—H⋯O interaction (Panunto et al., 1987 ▸), making it a weak hydrogen bond at best. The nonparallel intramolecular arrangement of the arene rings and the overall bent shape of the molecules of (I), among other factors, lead to a packing pattern (Fig. 2 ▸ b) in which π–π stacking interactions appear to be precluded.

Figure 2.

(a) Molecules of (I) are linked into dimers across centers of inversion by weak amine–nitro N—H⋯O hydrogen bonds (dashed lines). The view is onto the (010) plane. [Symmetry code: (#) −x + 1, −y + 1, −z + 1.] (b) An alternative view of the same set of molecules as in part (a), showing the nonparallel arrangement of the arene rings. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 70% probability level.

Enantiomeric N-(4-methylsulfonyl-2-nitrophenyl)-l-phenylalanine, (II), crystallizes in the noncentrosymmetric monoclinic space group C2 with one molecule in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 3 ▸). The absolute configuration was assigned based on the known configuration of the l-phenylalanine starting material and established through refinement of the Flack parameter (Parsons et al., 2013 ▸). As in (I), the amine H atom forms an intramolecular N—H⋯O hydrogen bond with the adjacent nitro group (Table 3 ▸). The C—O bond lengths of the carboxylic acid group are consistent with the placement of the acidic H atom on atom O6 [C9—O6 = 1.324 (3) Å] and with atom O5 being part of a free carbonyl group [C9—O5 = 1.191 (3) Å]. l-Phenylalanine (II) differs from 4-methylsulfonyl-2-nitro-N-(2-phenylethyl)aniline, (IV) (Wade et al., 2013 ▸), only in the presence of the carboxylic acid group on the phenylethyl group.

Figure 3.

The molecular structure of (II), showing the atom-labeling scheme and 70% probability displacement ellipsoids for the non-H atoms. The intramolecular hydrogen bond is shown as a dashed line.

As was the case with (I), the presence of this one additional group substantially changes the conformation of the molecule. The dihedral angle between the two arene rings is ca 62° in (II), but ca 107° in (IV). The difference is attributable primarily to the torsion angles C1—N1—C8—C10 [149.3 (2)° in (II) versus −175.70 (7)° in (IV)] and N1—C8—C10—C11 [−178.12 (18)° in (II) versus −61.20 (8)° in (IV)]. In addition, there are smaller but noticeable differences in the positioning of the nitro [O1—N2—C2—C1 torsion angle −20.2 (3)° in (II) versus −4.4 (1)° in (IV)] and methylsulfonyl [C7—S1—C4—C5 torsion angle 81.4 (2)° in (II) versus 110.98 (6)° in (IV)] groups.

Unlike (I), the molecules of (II) are not joined through intermolecular amine–nitro N—H⋯O hydrogen bonds. The molecules of (II) are positioned with the amine and nitro groups of adjacent molecules directed towards each other (Fig. 4 ▸

a), but the closest intermolecular distance, i.e. H1⋯O2(−x +  , y +

, y +  , −z + 1) of ca 3.1 Å, is too great even for a three-center hydrogen bond. Instead, molecules related by twofold rotation along the b axis are linked into dimers by two intermolecular O—H⋯O hydrogen bonds between the carboxylic acid and sulfone groups (Table 3 ▸). Similar O—H⋯O intermolecular interactions between hydroxy and sulfone groups have been observed in 4,4′-sulfonyldiphenol (Glidewell & Ferguson, 1996 ▸). These interactions and the chirality of the structure of (II) preclude the familiar inversion-related hydrogen bonding between carboxylic acid groups seen in many classic structures. The overall packing is such that the arene rings form a zigzag pattern (Fig. 4 ▸

b) that is devoid of π–π interactions between nearby parallel rings.

, −z + 1) of ca 3.1 Å, is too great even for a three-center hydrogen bond. Instead, molecules related by twofold rotation along the b axis are linked into dimers by two intermolecular O—H⋯O hydrogen bonds between the carboxylic acid and sulfone groups (Table 3 ▸). Similar O—H⋯O intermolecular interactions between hydroxy and sulfone groups have been observed in 4,4′-sulfonyldiphenol (Glidewell & Ferguson, 1996 ▸). These interactions and the chirality of the structure of (II) preclude the familiar inversion-related hydrogen bonding between carboxylic acid groups seen in many classic structures. The overall packing is such that the arene rings form a zigzag pattern (Fig. 4 ▸

b) that is devoid of π–π interactions between nearby parallel rings.

Figure 4.

(a) Molecules of (II) are linked into dimers across twofold axes of rotation by carboxylic acid–sulfone O—H⋯O hydrogen bonds (dashed lines). The view is onto the (010) plane. [Symmetry code: (#) −x + 2, y + 1, −z + 1.] (b) An alternative view of the packing showing the zigzag arrangement of the arene rings. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 70% probability level.

Recent unpublished work in our laboratory has indicated that molecules with more hydrophilic character have lower NO-release rates in aqueous solution than similar molecules with greater lipophilic character. We believe that molecules with higher HLB (more hydrophilic) form more organized micelles that restrict NO release, while molecules with lower HLB (more lipophilic) form less organized micelles that are less restrictive of NO release (Israelachvili, 2011 ▸). The presence of the carboxylic acid group on (II) would give it a greater hydrophilic balance than the previously reported 4-methylsulfonyl-2-nitro-N-(2-phenylethyl)aniline (Wade et al., 2013 ▸). On this basis, we would expect (II) to show a lower NO-release rate. By contrast, the addition of the two methoxy groups on (I) might be expected to lower the HLB relative to 2,4-dinitro-N-(2-phenylethyl)aniline (Wade et al., 2013 ▸); the melting point of (I) is 379 K, while that of the parent without the methoxy groups is 425 K, suggesting weaker intermolecular attractions in (I), leading to a higher NO-release rate. Ongoing experiments are underway to test these hypotheses and develop a better understanding of the relationship between structure and NO-release behavior.

Supplementary Material

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) global, C16H17N3O6, C16H16N2O6S. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229616005763/qs3054sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) C16H17N3O6. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229616005763/qs3054C16H17N3O6sup2.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) C16H16N2O6S. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229616005763/qs3054C16H16N2O6Ssup3.hkl

Acknowledgments

DKM acknowledges financial support for this project from the FRCE Committee (CMU) and the National Institute of Health (NIH) Award Number R15HL106600 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLB). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the NHLB or NIH. We thank Lee Daniels, Eric Reinheimer and Rigaku Oxford Diffraction for data collection and structure solution.

References

- Anter, E., Thomas, S. R., Schulz, E. & Shapiro, O. M. (2004). J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46637–46643. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cai, T. B., Wang, P. J. & Holder, A. A. (2005). Nitric Oxide Donors for Pharmaceutical and Biological Applications, edited by P. G. Wang, T. B. Cai & N. Taniguchi, pp. 3–31, 59–60. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.

- Cauwels, A. (2007). Kidney Int. 72, 557–565. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Clegg, W., Stanforth, S. P., Hedley, K. A., Raper, E. S. & Creighton, J. R. (1994). Acta Cryst. C50, 583–585.

- Curtis, B. M., Leix, K. A., Ji, Y., Glaves, R. S. E., Ash, D. E. & Mohanty, D. K. (2014). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 450, 208–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Curtis, B., Payne, T. J., Ash, D. E. & Mohanty, D. K. (2013). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21, 1123–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gangopadhyay, P. & Radhakrishnan, T. P. (2000). Chem. Mater. 12, 3362–3368.

- Giles, T. D. (2006). J. Clin. Hypertens. 8(s12), 2–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Glidewell, C. & Ferguson, G. (1996). Acta Cryst. C52, 2528–2530.

- Hambrecht, R., Adams, V., Erbs, S., Linke, A. & Krankel, N. (2003). Circulation, 107, 3152–3158. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hooft, R. W. W., Straver, L. H. & Spek, A. L. (2008). J. Appl. Cryst. 41, 96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Israelachvili, J. N. (2011). Intermolecular and Surface Forces, p. 535. Burlington, MA: Academic Press.

- Jeremy, J. Y., Rowe, D., Emsley, A. M. & Newby, A. C. (1999). Cardiovasc. Res. 43, 580–594. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jobgen, W. S., Fried, S. K., Wenjiang, J. F., Meininger, C. J. & Wu, G. (2006). J. Nutr. Biochem. 17, 571–588. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lagoda, G., Sezen, S. F., Hurt, K. J., Cabrini, M. R., Mohanty, D. K. & Burnett, A. L. (2014). FASEB J. 28, 76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lucas, D. L., Brown, R. A., Wassef, M. & Giles, T. D. (2005). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 1916–1924. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, J. O., Gladwin, M. T. & Weitzberg, E. (2015). Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 14, 623–641. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Miller, M. R. & Megson, I. L. (2007). Br. J. Pharmacol. 151, 305–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Miller, M. R., Okubo, K., Roseberry, M. J., Webb, D. J. & Megson, I. L. (2004). J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 43, 440–451. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Palmer, D. (2013). CrystalMaker. CrystalMaker Software Ltd, Yarnton, Oxfordshire, England.

- Panunto, T. W., Urbanczyk-Lipkowska, Z., Johnson, R. & Etter, M. C. (1987). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109, 7786–7797.

- Parsons, S., Flack, H. D. & Wagner, T. (2013). Acta Cryst. B69, 249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Payne, T. J., Thurman, C. R., Yu, H., Sun, Q., Mohanty, D. K., Squattrito, P. J., Giolando, M.-R., Brue, C. R. & Kirschbaum, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. C66, o369–o373. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rigaku (1998). REQAB. Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan.

- Rigaku (2010). CrystalStructure. Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan.

- Rigaku (2011). CrystalClear-SM Expert. Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2008). Acta Cryst. A64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2015). Acta Cryst C71, 3–8.

- Stasch, J. P., Pacher, P. & Evgenov, O. V. (2011). Circulation, 123, 2263–2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wade, C. B., Mohanty, D. K., Squattrito, P. J., Amato, N. J. & Kirschbaum, K. (2013). Acta Cryst. C69, 1383–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang, J., Teng, Y.-H., Yu, H., Oh-Lee, J. & Mohanty, D. K. (2009). Polym. J. 41, 715–725.

- Yu, H., Payne, T. J. & Mohanty, D. K. (2011). Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 78, 527–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z., Annich, G. M., Wu, Y. & Meyerhoff, M. E. (2006). Biomacromolecules, 7, 2565–2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) global, C16H17N3O6, C16H16N2O6S. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229616005763/qs3054sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) C16H17N3O6. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229616005763/qs3054C16H17N3O6sup2.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) C16H16N2O6S. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229616005763/qs3054C16H16N2O6Ssup3.hkl