“Wasn't that a great set of workshops on teaching residents in the fall? I had no idea there was so much to giving feedback to residents. There were so many ideas.”

“Yeah, that's true. I've been so busy, though, I haven't had time to try any yet.”

“And when I mentioned trying 1 or 2 new things at our meeting last month, everybody got annoyed and said things are fine the way they are. And then we started talking about our recent revenues.”

A key challenge for faculty development is ensuring that learning is transferred to the workplace. An effective program fosters the development of a particular blend of knowledge, dispositions, and behaviors1,2 that are applied and sustained over time. The role of expert clinician aside, faculty in academic institutions may not be formally prepared for the evolving range of roles3–6 and tasks7,8 they are asked to fulfill. Designing an effective faculty development program poses formidable challenges.9 While the literature offers ample guidance on designing faculty development episodes,10–12 perspectives on organized and comprehensive faculty development programs based on the principles of transfer of training13–15 are lacking.

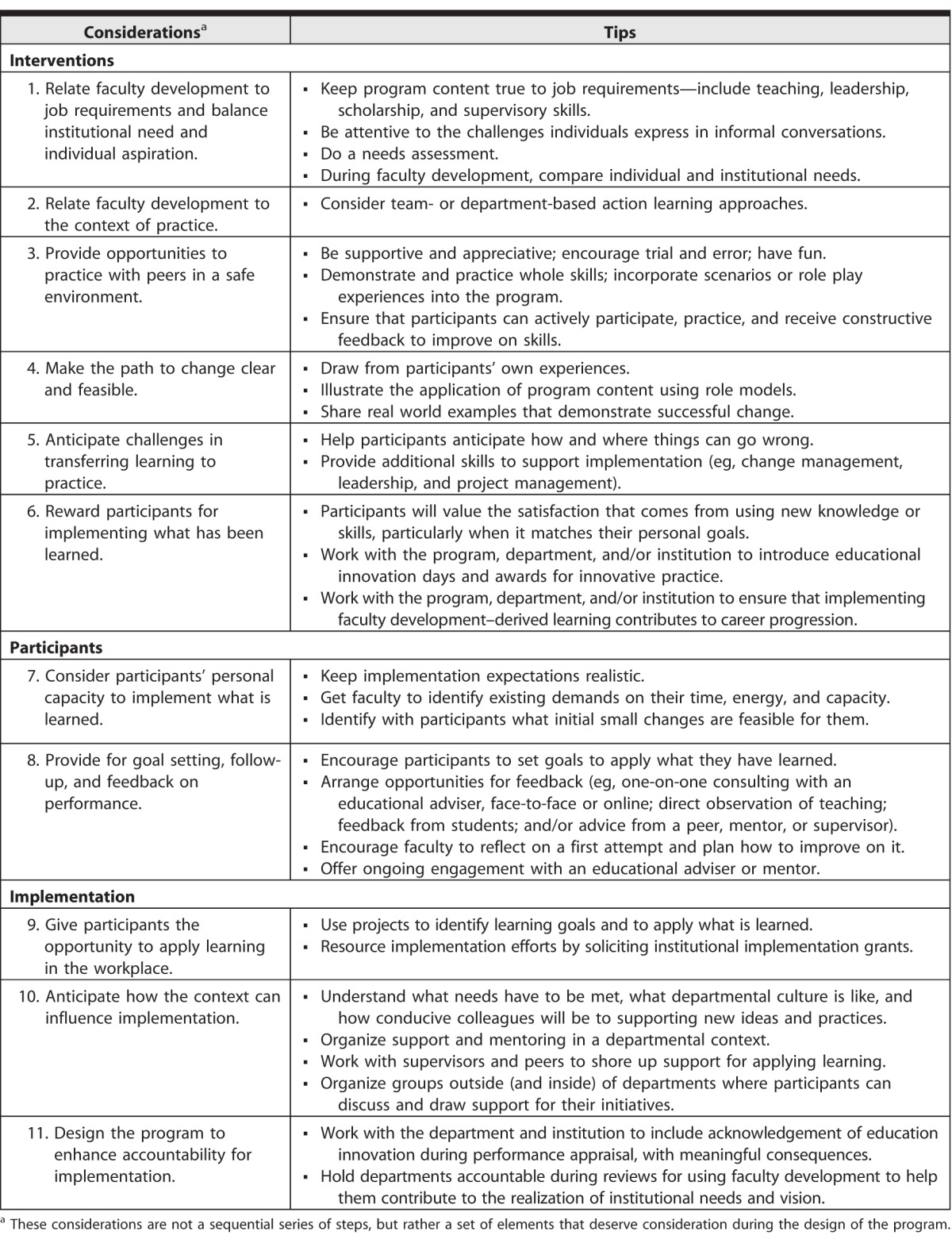

In this perspective, we highlight 11 key considerations for effective faculty development in an institutional context (table). Our aim is to guide individuals responsible for designing and implementing a development program with the goal of enhancing the transfer of learning into workplace practice.

table.

Key Considerations and Actions for an Effective Faculty Development Program in an Institutional Context

Interventions

1. Relate Faculty Development to Job Requirements and Balance Institutional Need and Individual Aspiration

The transfer of faculty development into the workplace is more likely to happen when program content is true to job requirements.13,14 Beyond teaching skills, content selection should reflect leadership and scholarly skills in education (eg, grant writing, research methods, publishing) and supervisory skills.3–6 The content for development sessions should be sensitive to the challenges that individual faculty members express, whether informally in meetings or corridor conversations or formally in a needs assessment used to gather faculty input and define areas of interest and need.16

From an institutional perspective, a faculty development program is more likely to be resourced when it supports institutional goals. From an individual perspective, the degree to which an institutionally responsive faculty development program will engage faculty depends partly on how committed faculty are to institutional values and goals.17 During faculty development sessions, the process should highlight individual needs and compare them to institutional priorities. If individual needs are not met, participants may not have sufficient motivation to transfer what they learn back into the workplace.13–15

2. Relate Faculty Development to the Context of Practice

Transfer is more likely to happen when the environment where the program takes place resembles the setting in which new knowledge and skills will be applied.13,15 Effective faculty development could use simulation and related approaches that facilitate in-situ learning18 (ie, training with, and within the norms of, the academic tribe that faculty members work with).9,19,20 Team- or department-based action learning approaches are worthy of consideration.3,18

3. Provide Opportunities to Practice With Peers in a Safe Environment

Ideally, faculty development occurs in a learning environment in which participants feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and ideas and practicing their developing skills. Development of complex skills requires deliberate instructional design,21,22 which should include demonstrating and practicing the whole skill.1,23 The design of the program should incorporate scenarios or role play experiences to ensure participants can actively participate, practice, and receive constructive feedback to improve their skills.1,14,15,24 Teachers and facilitators should be supportive and appreciative rather than judgmental, should encourage trial and error, and should create an atmosphere where participants have fun.

4. Make the Path to Change Clear and Feasible

It should be clear to those participating in faculty development how implementing the changes advocated in the program will lead to improved performance.13 Facilitators may draw from participants' own experiences, illustrate the application of program content using role models,1 or share real world examples that demonstrate successful change.

5. Anticipate Challenges in Transferring Learning to Practice

The approach to faculty development should help participants anticipate how and where things can go wrong.14,15 Facilitators should consider providing additional skills to support implementation (eg, change management, leadership, and project management).25,26

6. Reward Participants for Implementing What Has Been Learned

It should be realistic for participants to expect that implementing what they have learned will lead to valued outcomes.13–15 Value may be personal, with participants holding in high regard the satisfaction that comes from using new knowledge or skills. External regard and reward are also important.27 Participants' implementation efforts can be showcased at education innovation days and visibly rewarded with awards for innovative practice. Implementing faculty development–derived learning should contribute to career progression in a cumulative way.

Participants

7. Consider Participants' Personal Capacity to Implement What Is Learned

Expectations that are too onerous are less likely to result in transfer, and facilitators should consider the demands that faculty members have on their time, energy, and cognitive capacity.9,13 Even if participants value potential outcomes, they may not see how to fit change into their already demanding schedules. Facilitators can help participants identify what small changes are feasible for them.

8. Provide for Goal Setting, Follow-Up, and Feedback on Performance

The faculty development process should allow for participants to set goals to apply what they have learned, as well as arrange opportunities for feedback. This creates additional learning opportunities and helps ensure maintenance of new behaviors. Feedback can take the form of one-on-one consulting with an educational adviser (face-to-face or online), augmented or not by direct observation of teaching, feedback from students, and/or advice from a peer, mentor, or supervisor.4,9,18,24 Change may not work the first time around, and it is important to encourage and support participants to reflect on a first attempt13–15,18 and plan how to improve in future iterations. Ongoing engagement with an educational adviser or mentor can help.

Implementation

9. Give Participants the Opportunity to Apply Learning in the Workplace

Transfer to the workplace is aided by building opportunities to apply what has been learned into the design of the program.13–15 Activities in the workplace context are effective in bringing change.1,18,28 Using projects to identify learning goals and to apply what has been learned is an effective means of helping faculty members better understand and enhance their practice.6,20,25,26,29 Institutional grants for innovation—funded through strategic initiatives—can help resource the implementation of what has been learned.30

10. Anticipate How the Context Can Influence Implementation

It is important that faculty development facilitators understand the transfer climate14,15 in which participants will be expected to deploy new knowledge or skills. Critical questions include the following: What needs have to be met? What is departmental culture like? How conducive will the environment be to supporting new ideas and practices?15,20 This aspect of the process should consider if there is adequate support and mentoring, and if implementation efforts may benefit from prior discussions with supervisors and peers to shore up support for the use of what has been learned.13–15,20,24 Beyond departments, it may be beneficial to create a community of practice that participants can belong to1,9,24,27 by organizing groups where participants can discuss and draw support for their initiatives.

11. Design the Program to Enhance Accountability for Implementation

Finally, transfer of faculty development to the workplace is better ensured by enhanced accountability for implementation at the level of the individual, the department, or the cross-departmental team for a larger collaborative effort, such as the design of an integrated curriculum. This should encompass acknowledgement of education innovation during performance appraisal, and equally, some meaningful consequences if desired outcomes are not achieved.13,14 Departments should be held accountable during internal evaluation reviews that explore whether the department is contributing to the realization of institutional needs and vision, and how faculty development contributes to this process.

Conclusions

The goal of any faculty development program is for participants to leave with and utilize new knowledge and perspectives, regardless of the context or motives for their participation. Creating effective faculty development episodes is important, but maximum effect requires a systematic approach that includes shaping an enabling practice environment in which participants can translate the learning into practice.

References

- 1. Irby DM. Excellence in clinical teaching: knowledge transformation and development required. Med Educ. 2014; 48 8: 776– 784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shulman LS. Knowledge and teaching: foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educ Rev. 1987; 57 1: 1– 23. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Steinert Y. Faculty Development in the Health Professions. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilkerson L, Irby DM. Strategies for improving teaching practices: a comprehensive approach to faculty development. Acad Med. 1998; 73 4: 387– 396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leslie K, Baker L, Egan-Lee E, Esdaile M, Reeves S. Advancing faculty development in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013; 88 7: 1038– 1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Steinert Y. Perspectives on faculty development: aiming for 6/6 by 2020. Perspect Med Educ. 2012; 1 1: 31– 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carraccio C, Iobst WF, Philibert I. Milestones: not millstones but stepping stones. J Grad Med Educ. 2014; 6 3: 589– 590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swing SR, Clyman SG, Holmboe ES, Williams RG. Advancing resident assessment in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2009; 1 2: 278– 286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O'Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Reframing research on faculty development. Acad Med. 2011; 86 4: 421– 428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McLean M, Cilliers F, Van Wyk JM. Faculty development: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Med Teach. 2008; 30 6: 555– 584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kirkham D, Baker P. Twelve tips for running teaching programmes for newly qualified doctors. Med Teach. 2012; 34 8: 625– 630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Grave W, Zanting A, Mansvelder-Longayroux DD, Molenaar WM. Workshops and seminars: enhancing effectiveness. : Steinert Y. Faculty Development in the Health Professions. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer; 2014: 181– 195. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holton EF, III, Bates RA, Ruona WEA. Development of a generalized learning transfer system inventory. Human Res Develop Q. 2000; 11 4: 333– 360. [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Rijdt C, Stes A, van der Vleuten C, Dochy F. Influencing variables and moderators of transfer of learning to the workplace within the area of staff development in higher education: research review. Educ Res Rev. 2013; 8: 48– 74. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grossman R, Salas E. The transfer of training: what really matters. Intl J Train Develop. 2011; 15 2: 103– 120. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Danilkewich AD, Kuzmicz J, Greenberg G, Gruszczynski A, Hosain J, McKague M, et al. Implementing an evidence-informed faculty development program. Can Fam Physician. 2012; 58 6: e337– e343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baldwin TT, Ford JK, Blume BD. Transfer of training 1988–2008: an updated review and agenda for future research. Intl Rev Industrial Org Psych. 2009; 24: 41– 70. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prebble T, Hargraves H, Leach L, Naidoo K, Suddaby G, Zepke N. Impact of student support services and academic development programmes on student outcomes in undergraduate tertiary study: a synthesis of the research. https://www.academia.edu/1415924/Impact_of_student_support_services_and_academic_development_programmes_on_studen t_outcomes_in_undergraduate_tertiary_study_A_synthesis_of_ the_research. Accessed January 15, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trowler P, Saunders M, Bamber V. Tribes and Territories in the 21st Century: Rethinking the Significance of Disciplines in Higher Education. London, England: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Williams BC, Weber V, Babbott SF, Kirk LM, Heflin MT, O'Tolle E, et al. Faculty development for the 21st century: lessons from the Society of General Internal Medicine–Hartford collaborative centers for the care of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007; 55 6: 941– 947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Merrienboer JJG, Kirschner PA, Kester L. Taking the load off a learner's mind: instructional design for complex learning. Educ Psychologist. 2003; 38 1: 5– 13. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Young JQ, Van Merrienboer J, Durning S, ten Cate O. Cognitive load theory: implications for medical education: AMEE Guide No. 86. Med Teach. 2014; 36 5: 371– 384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lim J, Reiser RA, Olina Z. The effects of part-task and whole-task instructional approaches on acquisition and transfer of a complex cognitive skill. Educ Tech Res Dev. 2009; 57: 61– 77. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, Dolmans D, Spencer J, Gelula M, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Med Teach. 2006; 28 6: 497– 526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burdick WP, Friedman SR, Diserens D. Faculty development projects for international health professions educators: vehicles for institutional change? Med Teach. 2012; 34 1: 38– 44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mennin S, Kalishman S, Eklund MA, Friedman S, Morahan PS, Burdick W. Project-based faculty development by international health professions educators: practical strategies. Med Teach. 2013; 35 2: e971– e977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. van Schalkwyk S, Cilliers FJ, Adendorff H, Cattell K, Herman N. Journeys of growth towards the professional learning of academics: understanding the role of educational development. Intl J Acad Develop. 2012; 18 2: 139– 151. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eraut M. Informal learning in the workplace. Studies Contin Educ. 2004; 26 2: 247– 273. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gusic ME, Milner RJ, Tisdell EJ, Taylor EW, Quillen DA, Thorndyke LE. The essential value of projects in faculty development. Acad Med. 2010; 85 9: 1484– 1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Adler SR, Chang A, Loeser H, Cooke M, Wang J, Teherani A. The impact of intramural grants on educators' careers and on medical education innovation. Acad Med. 2015; 90 6: 827– 831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]