Imagine that you are a program director with limited instructional time, and you have developed supplementary e-learning modules, but your residents do not seem to use them. You have put significant effort into their design, as the modules contain important information that residents should want to learn.

Concerned, you want to understand why this happened, so you decide to conduct a survey to explore the issue. However, despite an acceptable response rate, the results do not answer your questions. The survey data indicate that residents enjoy the modules and recognize that they cover important materials, yet the modules continue to be sparsely used. You have a suspicion that the problem may be time management or the online format, but these insights come from everyday involvement with the residents, rather than from the survey data. You wonder what method would help you gain a genuine sense of how residents manage their time and prioritize their learning, and how the modules would fit into that.

Because you are not sure if residents are consciously aware of how they manage their competing priorities, how can you empirically explore the issue?

About Ethnography

Ethnography is an ideal methodology to help understand the everyday challenges that shape graduate medical education (GME). Ethnography refers to a qualitative research project with the goal of offering a rich and detailed description of everyday life. Ethnographic research is becoming more popular in medical education,1–4 as it offers a method to rigorously investigate the taken-for-granted, but telling, facets of culture that make us who we are.

The goal of ethnography is “thick description.”5,6 This means that the ethnographer goes beyond simply observing and describing the details of a particular event. Rather, he or she seeks to explain how these events represent cultural “webs of meaning.”6 The ethnographer interprets these webs of meaning through an “emic” perspective, meaning an insider's point of view. The emphasis is on becoming immersed in the context and exploring the culture of the study setting.

An emic perspective allows researchers to offer a nuanced understanding of perennial issues in GME, like the topic of reduced work hours. Much of the research on duty hours focuses on questions related to safety,7 sleep,8 and the impact on training.9 While these are important issues, there is a gap in the literature with respect to studies that investigate the cultural values and priorities of various invested parties (eg, educational institutions, hospital settings, individual learners, and faculty) that are driving the conversations about topics such as duty hours.

In sum, ethnography allows us to look deeply at the institutional practices and cultural issues, offering a new perspective on this challenging area.

Characteristics of Ethnographic Research

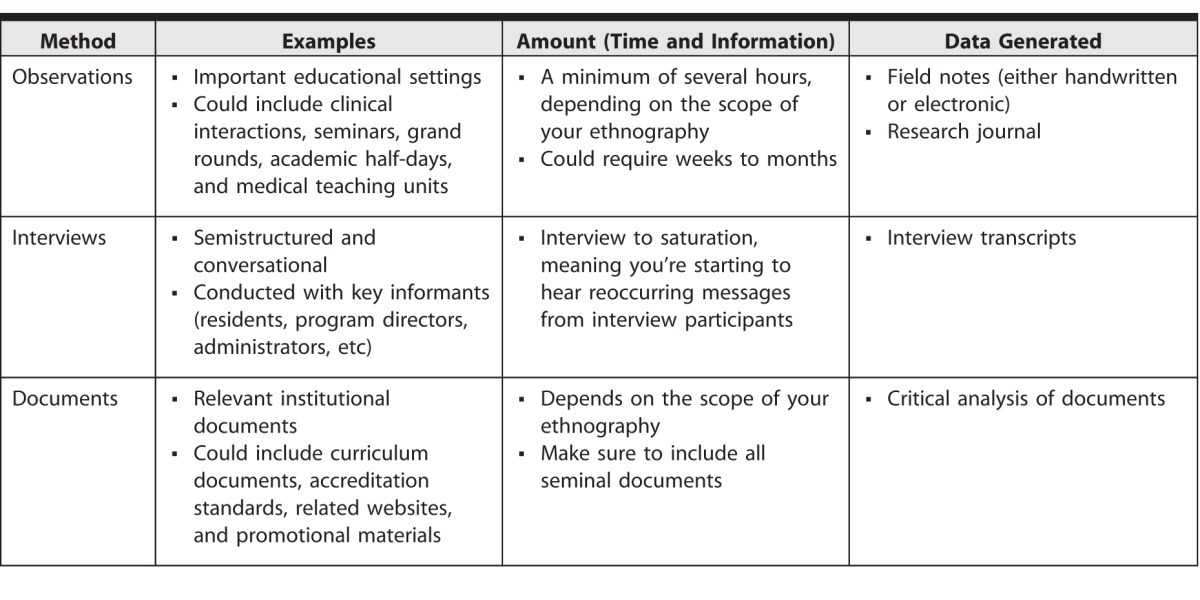

To understand culture in-depth, ethnographers use “layered” data collection strategies. The 3 most common strategies include observations, interviews, and document analysis. See the table for practical considerations related to each data collection approach.

table.

Practical Considerations for Ethnographic Graduate Medical Education Research

Observations

An emic perspective means that researchers engage in observational data collection. Typically, ethnographers spend long periods of time and become personally invested in the places (often called “the field”) where they conduct their research. This time commitment and personal involvement may seem daunting; however, as graduate medical educators, we are engaging in a type of informal ethnographic fieldwork every day. We learn about education by virtue of conducting our work. Ethnography offers a means of formalizing this fieldwork, facilitating the gathering of empirical insights into social practices that are normally “hidden” from the public gaze.3

Interviews

Ethnographic interviews often follow observations and are based on insight gathered from the observational fieldwork. Each ethnographer brings his or her own unique approach to the interview; however, the emphasis is on eliciting participants' insights without being limited by predefined choices. In most cases, an ethnographic interview is conversational in tone, with the purpose of helping researchers learn more about culture and context.

Document Analysis

Critical document analysis adds another important layer of richness. Given the goal of understanding culture, ethnographers consider documents to be cultural artifacts that offer insights and represent a documentary version of social reality.10 Thus, ethnographers critically explore how documents affect people, and in contrast, how people work with and against documents. Relevant documents include curricula, policies, accreditation standards, and information on websites.

Each of these methods adds richness to researchers' understanding of the topic or issue under study. In combining data from observations, interviews, and documents, researchers are able to look more closely and rigorously at the complex issues in GME.

A Focus on Culture

Ethnographies help us understand the interactions, behaviors, and perceptions that occur within groups.4 Atkinson and Hammersley11 describe the role of the ethnographer as “getting inside” a cultural group in order to understand how that group makes sense of the world. The ethnographic focus is on an enhanced understanding of the culture, which is defined as “a system of resources used by participants in the negotiation and discovery of everyday interactions.”9 Culture encompasses aspects such as language, professional activities, educational backgrounds, social class, and other related factors.

Medical education historically has been an enterprise focused on developing competent physicians.12 However, there are multiple and competing cultural influences on any given learning experience, including those of educational institutions, individual learners, attending physicians, and the profession as a whole. Ethnography helps us to understand the complexity of GME by considering the interactions of these multiple influences.

Consider competency-based medical education (CBME). Currently, many programs are competency-based, or working toward it.13–16 Much of the current CBME literature focuses on assessment issues, but there are broader cultural questions related to CBME that need to be addressed. What about other considerations (such as the intrinsic aspects of teaching and learning)17 that are not measured or captured through formal assessments? For example, how does CBME influence the development of professional identity? What does it mean for an individual learner to be immersed in a culture of competence? How is the shift to CBME experienced by learners, teachers, and administrators?

Ethnographic research would help us understand the complexity of the cultural shift that results from the adoption of CBME by providing tools to explore, in-depth, the multiple changes involved. By layering data collection approaches (eg, observations, interviews, and documents), researchers can generate a rich picture of GME culture in the age of CBME.

Why Ethnography?

In conclusion, there is a well-established tradition of ethnographic research in medicine18 and an emerging body of work in medical education.1,2 See the box for further readings. By generating holistic accounts of topics in GME, ethnography lends insight into the social and cultural considerations characterizing our educational settings.

box Further Reading on Ethnography

Resources on Ethnography in Medical Education

-

•

Atkinson P, Pugsley L. Making sense of ethnography and medical education. Med Educ. 2005;39(2):228–234.

-

•

Goodson L, Vassar M. An overview of ethnography in healthcare and medical education research. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2011;8:4.

-

•

Reeves S, Peller J, Goldman J, Kitto S. Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE Guide No. 80. Med Teach. 2013;35(8):e1365–e1379.

-

•

Reeves S, Kuper A, Hodges BD. Qualitative research methodologies: ethnography. BMJ. 2008;337:a1020.

Classic Ethnography Resources

-

•

Geertz C. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1973.

-

•

van Maanen J. Tales of the Field: On Writing Ethnography. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2011.

Using ethnographic methods allows researchers to collect information directly from the source. Researchers actually spend time in the settings they are studying, rather than simply hearing about them through participant surveys. This is of the utmost importance, because what research participants tell you they do, what they actually do, and what they think they do are not necessarily one and the same.

The account emerging through ethnographic research is a rich and valuable one—and one that could be easily rendered invisible in other types of research. Given recent developments in the field, ethnographic research is an important tool for GME researchers.

References

- 1. Atkinson P, Pugsley L. Making sense of ethnography and medical education. Med Educ. 2005; 39 2: 228– 234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goodson L, Vassar M. An overview of ethnography in healthcare and medical education research. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2011; 8: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reeves S, Peller J, Goldman J, Kitto S. Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE Guide No. 80. Med Teach. 2013; 35 8: e1365– e1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reeves S, Kuper A, Hodges BD. Qualitative research methodologies: ethnography. BMJ. 2008; 337: a1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Maanen J. Tales of the Field: On Writing Ethnography. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Geertz C. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harris JD, Staheli G, LeClere L, Andersone D, McCormick F. What effects have resident work-hour changes had on education, quality of life, and safety? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014; 473 5: 1600– 1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Veddeng A, Husby T, Engelsen IB, Kent A, Flaatten H. Impact of night shifts on laparoscopic skills and cognitive function among gynecologists. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014; 93 12: 1255– 1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lachance S, Latulippe JF, Valiquette L, Langlois G, Douville Y, Fried GM, et al. Perceived effects of the 16-hour workday restriction on surgical specialties: Quebec's experience. J Surg Educ. 2014; 71 5: 707– 715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Atkinson P, Coffey A. Analysing documentary realities. : Silverman D. Qualitative Research: Theory, Method, and Practice. 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2004: 56– 75. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Atkinson P, Hammersley M. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Tavistock Publications Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Foucault M. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. New York, NY: Pantheon Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holmboe ES. Realizing the promise of competency-based medical education. Acad Med. 2015; 90 4: 411– 413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iobst WF, Sherbino J, ten Cate O, Richardson DL, Dath D, Swing SR, et al. Competency-based medical education in postgraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2010; 32 8: 651– 656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Teherani A, Chen HC. The next steps in competency-based medical education: milestones, entrustable professional activities, and observable practice activities. J Gen Intern Med. 2014; 29 8: 1090– 1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. ten Cate O, Billett S. Competency-based medical education: origins, perspectives, and potentialities. Med Educ. 2014; 48 3: 325– 332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sherbino J, Frank JR, Flynn L, Snell L. “Intrinsic roles” rather than “armour”: renaming the “non-medical expert roles” of the CanMEDS framework to match their intent. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011; 16 5: 695– 697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Becker HS, Geer GB, Hughes EC, Strauss AL. Boys in White: Student Culture in Medical School. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]