Abstract

Introduction:

Hydropneumothorax is an abnormal presence of air and fluid in the pleural space. Even though the knowledge of hydro-pneumothorax dates back to the days of ancient Greece, not many national or international literatures are documented.

Aim:

To study clinical presentation, etiological diagnosis, and management of the patients of hydropneumothorax.

Materials and Methods:

Patients admitted in a tertiary care hospital with diagnosis of hydropneumothorax between 2012 and 2014 were prospectively studied. Detailed history and clinical examination were recorded. Blood, pleural fluid, sputum investigations, and computed tomography (CT) thorax (if necessary) were done. Intercostal drainage (ICD) tube was inserted and patients were followed up till 3 months.

Results:

Fifty-seven patients were studied. Breathlessness, anorexia, weight loss, and cough were the most common symptoms. Tachypnea was present in 68.4% patients. Mean PaO2 was 71.7 mm of Hg (standard deviation ±12.4). Hypoxemia was present in 35 patients (61.4%). All patients had exudative effusion. Etiological diagnosis was possible in 35 patients by initial work-up and 22 required CT thorax for arriving at a diagnosis. Tuberculosis (TB) was etiology in 80.7% patients, acute bacterial infection in 14%, malignancy in 3.5%, and obstructive airway disease in 1.8%. All patients required ICD tube insertion. ICD was required for 24.8 days (±13.1).

Conclusion:

Most patients presented with symptoms and signs of cardiorespiratory distress along with cough, anorexia, and weight loss. Extensive pleural fluid analysis is essential in establishing etiological diagnosis. TB is the most common etiology. ICD for long duration with antimicrobial chemotherapy is the management.

KEY WORDS: Hydropneumothorax, intercostal drainage, tuberculosis

INTRODUCTION

Hydropneumothorax is the abnormal presence of air and fluid in the pleural space. The knowledge of hydropneumothorax dates back to the days of ancient Greece when the Hippocratic succussion used to be performed for the diagnosis.[1] There have been tremendous advancements in the field of laboratory and radiological diagnosis and therapeutic management for pleural pathologies. However, not many national or international literature are documented regarding hydropneumothorax. The purpose of this study is to throw light on the clinical presentation, etiological diagnosis, and management profile of the patients of hydropneumothorax.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective, observational, hospital-based study was conducted. Population studied was patients of adult age group attending a tertiary hospital in Western India for a period of approximately 2 years. Only patients of hydropneumothorax diagnosed on clinical and radiological grounds were considered. Traumatic hydropneumothorax was excluded from the study. Patients who satisfied the inclusion criteria were then explained about the study and valid consent taken for their participation. All the patients were enquired regarding symptoms such as breathlessness, fever, cough, chest pain, constitutional symptoms such as loss of appetite and loss of weight. Patients were also enquired regarding presence of comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and history of tuberculosis (TB) and immunocompromised state. Detailed clinical examination was done. Patients underwent initial laboratory examination of arterial blood gases examination, complete blood count, random blood sugars, serum proteins, and serum lactate dehydrogenase. Sputum for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) was examined by Ziehl–Neelsen stain. Pleural fluid was subjected to pathological (routine microscopy), biochemical (proteins, glucose, cholesterol, lactate dehydrogenase, and adenosine deaminase [ADA] levels), and microbiological examination (bacterial culture and drug sensitivity, fungal culture and sensitivity, Lowenstein–Jenson culture, and pleural fluid for AFB staining). Due to technical difficulties, mycobacterial growth indicator tube (MGIT) culture of all patients was not sent. In patients in whom diagnosis could not be established by above investigations were subjected to computed tomography (CT) (contrast-enhanced with high resolution CT). All patients were treated with intercostal drainage (ICD) tube insertion. As per the etiological diagnosis, patients were treated on medical grounds as well. Patients were followed-up for 3 months with weekly ICD status and chest X-ray examination. ICD tube was clamped and removed when air-leak stopped and drainage of pleural fluid was below 50 ml/day and chest X-ray showed complete lung expansion. Number of days required for the same was documented. All the data were initially entered in Microsoft Excel and later transferred to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) SPSS Inc. Released 2008. SPSS statistics for Windows, version 17.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc. All the variables of hydropneumothorax were analyzed separately and as per their type and distribution, appropriate test was applied and analyzed in the SPSS software version 17.0.

RESULTS

Fifty-seven patients of hydropneumothorax were included in the study. Mean age of presentation was 44.2 years (±16.3 years). Forty-six out of 57 (80.7%) patients were males. Breathlessness was the most common presenting symptom seen in 54 patients (94.7%), followed by cough seen in 53 patients (93%), fever was seen in 50 patients (87.7%), chest pain in 41 patients (71.9%), weight loss in 39 (68.4.2%), and loss of appetite in 53 patients (93.2%). History of pulmonary TB was present in 18 patients (31.6%) and smoking addiction was present in 21 patients (36.8%). Diabetes mellitus was present in 12 patients (21.1%). Eight patients (14.0%) had hypotension at presentation, four patients (7%) were hypertensive, and rest 45 (78.9%) had normal blood pressure. Twenty-eight patients (49.1%) had tachycardia and tachypnea was present in 39 patients (68.4%) of hydropneumothorax.

Mean pH of patients was 7.4 (standard deviation [SD] ±0.1), mean Paco2 was 35.1 mm of Hg (SD ± 10.2), Pao2 was 71.7 mm of Hg (SD ± 12.4), and mean HCO3 was 21.4 mEq (SD ± 4.3). Hypoxemia was present in 35 patients (61.4%). Sputum examination for AFB by Ziehl–Neelsen staining was positive in 10 patients (17.5%).

Pleural fluid biochemistry showed protein of 4.46 g/dL (±0.9 g/dL) and glucose of 32.6 mg/dL (SD ± 41.56). On the basis of Light's criteria, all patients had exudative pleural effusion. Pleural fluid was lymphocyte predominant in 41 patients (71.9%) and polymorph predominant in the remaining 16 patients.

Pleural fluid AFB smear was positive in eight patients (14%) and Lowenstein–Jenson media showed growth of TB bacilli in five patients (9%). Due to technical difficulties, MGIT of 42 patients were sent, of which positive growth was seen in 10 patients (23.9%). Pleural fluid bacterial culture was positive in seven patients (12.3%). Etiological diagnosis was possible in 35 patients with the above clinical and laboratory investigations.

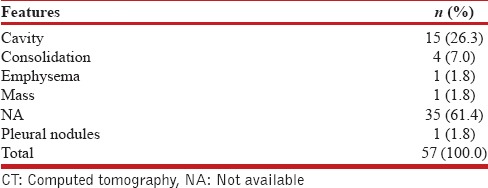

Remaining 22 [Table 1] patients required CT thorax in which cavitary consolidation with V-Y pattern was seen in 15 patients (26.3%) suggestive of TB, consolidation with air-bronchogram was seen in 15 patients suggestive of acute bacterial infection, emphysematous changes were seen in only one patient (1.8%) suggestive of obstructive airway disease, and pleural nodules and mass lesion suggestive of malignancy was seen in one patient each (1.8%).

Table 1.

CT scan features

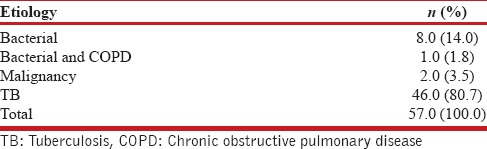

TB [Table 2] was the most common etiological diagnosis seen in 46 patients (80.7%), acute bacterial infection was noted in eight patients (14%), malignancy in two patients (3.5%), and obstructive airway disease with bacterial infection in one patient (1.8%).

Table 2.

Etiology for pneumothorax

All patients were treated with insertion of ICD tube. Mean number of days of ICD tube in situ was 24.8 days (SD ± 13.1 days). Only 22.81% patients had complete improvement with ICD tube removal within 15 days. Majority of patients (43.86%) had complete improvement between 15 days and 1 month. ICD was required for more than 30 days in 33.3% patients in whom 14 patients (73.68%) had TB, three patients had bacterial etiology, and two patients had malignancy. All seven patients (12.3%) continued ICD for more than 3 months who had TB.

DISCUSSION

Hydropneumothorax has been common entity in this country. However, only isolated case reports have been documented on hydropneumothorax and there has been a dearth of large case studies. Majority of patients presented with symptoms of acute respiratory compromise that is breathlessness due to ventilation perfusion mismatch and cough due to pleural involvement; however, fever and constitutional symptoms such as weight loss and anorexia were also commonly seen probably due to TB being the major etiology. This correlated with studies done by Gupta et al.[2] and Javaid et al.[3] where breathlessness was the most common presenting symptom and present in 93% and 98% patients, respectively. However, these were studies on pneumothorax. The above symptoms of respiratory distress were associated with signs of tachypnea in 68% of patients and objective evidence of hypoxemia in 61% of all patients in arterial blood gases. In our study, it was noted that pleural fluid AFB smear was positive in 14%, which correlates with a study by Heyderman et al.[4] In our country where prevalence of TB is high, rupture of cavity or TB focus could be the cause of pneumothorax or hydropneumothorax. Light originally developed Light's criteria with the goal to identify all exudates correctly and the criteria are remarkably effective in achieving this goal.[5] On applying Light's criteria, all patients in our study had exudative pleural effusion. In our study, pleural fluid differential count showed lymphocyte predominant in 72% patients and 91% of these patients had TB as etiology, which correlates with an Indian study in which 96% of lymphocyte predominant pleural fluid were due to TB.[6] Pleural fluid ADA was raised in 77% of our patients, out of which 93% patients were having TB as an etiology thus proving that determination of ADA levels has high accuracy in the diagnosis of the pleural TB and should be used as a routine test in its investigation.[7] Of the 42 patients whose pleural fluid for MGIT culture was done, positive growth was in 24% that had a better yield than Lowenstein–Jenson media which showed growth of TB bacilli in 9% patients. This finding correlates with a 2001 study by Luzze et al.[8] CT thorax was required in only 22 patients for etiological diagnosis as task was made easier by the analysis of pleural fluid and initial battery of tests, which led to a diagnosis. TB was by far the most common etiological diagnosis (80.7%), thus further consolidating the fact that TB is the most common chronic infectious pleuroparenchymal disease in India. ICD was inserted in all the patients and drainage was required for longer than 30 days in 33.3% patients. This is usually the case seen in practice where the tube remains for longer time draining some amount of fluid due to underlying TB and most of these patients had bronchopleural fistula as evident by prolonged air leak in ICD. Multiple loculations and adhesions were noted in chest X-ray also which contributes for prolonged ICD. The duration of tube thoracostomy ranged from 5 days to 6 months, with a mean duration of 50 days in the series by Wilder et al.[9] Thoracoscopy or other interventions were not performed due to lack of availability in our institute.

CONCLUSION

From our study, it could be concluded that most patients presented with symptoms and signs of cardiorespiratory distress along with cough, anorexia, and weight loss which alerted toward diagnosis. Extensive pleural fluid analysis and investigations including microbiological and biochemical work-up is the cornerstone in establishing etiological diagnosis in hydropneumothorax. TB remains the most common etiology for hydropneumothorax. ICD tube insertion remains the management along with antimicrobial chemotherapy. However, ICD is required for longer durations. As there is paucity in the literature about hydro-pneumothorax, further research is required to aid in the appropriate management of the same.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Emerson CP. Charles P. Pneumothorax: A Historical, Clinical and Experimental Study. [Baltimore, 1903] 1903. [Last cited on 2013 Oct 17]. p. 466. Available from: http://www.archive.org/details/pneumothoraxhist00emer .

- 2.Gupta D, Mishra S, Faruqi S, Aggarwal AN. Aetiology and clinical profile of spontaneous pneumothorax in adults. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:261–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Javaid A, Amjad M, Khan W, Samad A, Khan MY, Sadiq M, et al. Pneumothorax. Is it a different disease in the east? [Last cited on 2013 Dec 01];J Postgrad Med Inst. 2011 11(2):157–61. Available from: http://www.jpmi.org.pk/index.php/jpmi/article/view/578 . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heyderman RS, Makunike R, Muza T, Odwee M, Kadzirange G, Manyemba J, et al. Pleural tuberculosis in Harare, Zimbabwe: The relationship between human immunodeficiency virus, CD4 lymphocyte count, granuloma formation and disseminated disease. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:14–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Light RW. Pleural Diseases. Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. p. 456. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kushwaha R, Shashikala P, Hiremath S, Basavaraj H. Cells in pleural fluid and their value in differential diagnosis. J Cytol. 2008;25:138. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morisson P, Neves DD. Evaluation of adenosine deaminase in the diagnosis of pleural tuberculosis: A Brazilian meta-analysis. J Bras Pneumol. 2008;34:217–24. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132008000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luzze H, Elliott AM, Joloba ML, Odida M, Oweka-Onyee J, Nakiyingi J, et al. Evaluation of suspected tuberculous pleurisy: Clinical and diagnostic findings in HIV-1-positive and HIV-negative adults in Uganda. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:746–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilder RJ, Beacham EG, Ravitch MM. Spontaneous pneumothorax complicating cavitary tuberculosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1962;43:561–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]