CASE REPORT

An 18-year-old female student, a never smoker, HIV-negative, was referred to our Institute for evaluation of exertional breathlessness, cough with minimal mucoid sputum and fever of 1.5 years duration. She had lost 15 kg weight over the past 6 months. Prior to the presentation, based on her clinical and radiological profile, she had received antituberculous therapy for 4 months with no relief.

On examination, she was tachypnoeic and dyspnoeic but afebrile. Digital clubbing was observed. Vesicular breath sounds with fine inspiratory crackles were audible in all areas of the chest wall. Oxygen saturation on room air was 54%. Arterial blood gas analysis on oxygen (4 lt/min) showed pH 7.40, PCO238.7 mmHg, PO257.6 mmHg, and SaO2 of 90%. The total leucocyte count was 5.43 × 103 cells/μL with a normal differential count.

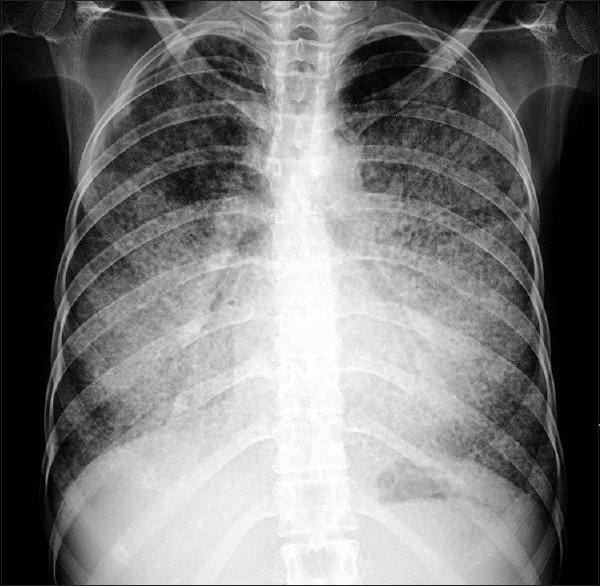

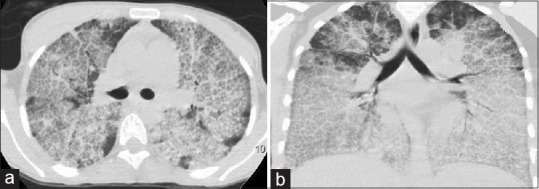

Chest radiograph is shown in Figure 1 and high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the thorax is shown in Figure 2. Sputum stains and cultures for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, fungi and other aerobic organisms were negative. Fiber-optic bronchoscopy did not visualize any gross abnormality. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was milky in appearance but stains and cultures were negative for aerobic organisms including M. tuberculosis and pathogenic fungi. The BAL fluid was sent for a special investigation.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray posteroanterior view showing showed bilateral, diffuse alveolar opacities having a perihilar and basal distribution with sparing of the apices

Figure 2.

High-resolution computed tomography chest (a) (lung window) and (b) (coronal section). The anterior part of both the lung fields show typical crazy-paving pattern with central ground-glassing and peripheral interlobular septal thickening. In the dependent part of the lung, there is an increased density secondary to the gravitational accumulation of lipo-proteinaceous fluid

QUESTIONS

Q1: What is the radiological description?

Q2: What is this characteristic pattern on HRCT known as?

Q3: What is the differential diagnosis of “Crazy-paving” pattern on HRCT?

Q4: What was the clinical diagnosis in this patient?

Q5: How was the diagnosis achieved?

Q6: What are the current modalities available for treatment of this condition?

ANSWERS

A1: Chest radiograph [Figure 1] showed bilateral, diffuse alveolar opacities having a perihilar and basal distribution with sparing of the apices while the HRCT of the thorax [Figure 2] demonstrated bilateral diffuse ground-glass opacities (GGO) superimposed with interlobular and intralobular septal thickening in a geographical distribution resembling irregularly laid cobblestones on a pavement. These areas of “Crazy-paving” were bilateral and sharply demarcated from the normal lung parenchyma creating a “geographic” pattern.

A2: This appearance is characteristically described as “Crazy-paving” pattern. The reticular network in “Crazy-paving” pattern is thought to represent the thickened interlobular septa while the GGO reflect the alveolar filling with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive material.[1] The mechanisms thought to be responsible for this pattern include alveolar filling processes, interstitial fibrotic processes, or a combination of both.[2]

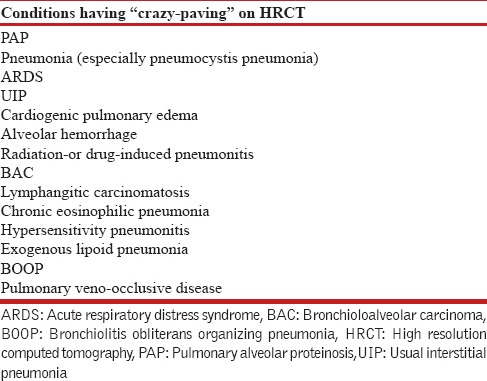

A3: “Crazy-paving” pattern on HRCT was at one time considered diagnostic of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP). However, this pattern has now been recognized in several other conditions which are listed in Table 1.[1,3,4]

A4: PAP.

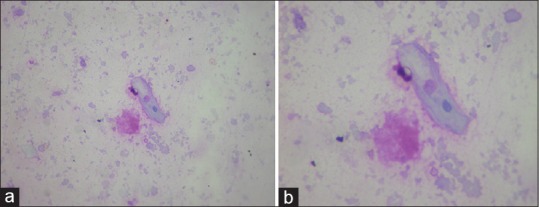

A5: The diagnosis was suspected due to the characteristic features seen on HRCT supported by the milky appearance of BAL. It was substantiated by the microscopic examination of the bronchial aspirate which showed granular eosinophilic exudate that was PAS stain positive [Figure 3]. The diagnosis of PAP is commonly established on the basis of the characteristic imaging feature on HRCT along with cytopathological evaluation of the BAL fluid. However, open lung biopsy (OLB) continues to remain as the gold standard for diagnosis of PAP.

A6: Whole-lung lavage (WLL) developed by Ramirez and Campbell[5] has been the standard of care for the treatment especially, in patients with idiopathic PAP. This procedure is done under general anesthesia and involves removal of lipo-proteinaceous material from the alveoli using saline solution and chest percussion. This leads to symptomatic, radiological, and functional improvement in 85% of patients of PAP.[6] Following WLL, the median symptom-free period is 15 months and if required repeat sessions of WLL can be done.[7] The major complication associated with this procedure is hypoxemia with other less common ones being pneumothorax, pleural effusion, and hydropneumothorax[8]

Table 1.

Figure 3.

(a) High power view (×40) showing a benign squamous epithelial cells and periodic acid-Schiff positive granular material. (b) Zoom of the previous picture showing the epithelial cell and granular material

Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) supplemental therapy has a role in the management of idiopathic PAP.[9] GM-CSF therapy can be given either by inhaled or subcutaneous route and it can be considered supplemental to WLL with response rates of 50%[9]

Newer modalities of treatment include administration of Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 antigen of B-lymphocytes. It helps in decreasing the concentration of anti-GM-CSF antibodies through the depletion of B-cells.[4] Rituximab is useful in patients not responsive to WLL or GM-CSF therapy. Plasmapheresis is a novel technique which involves removal of the anti-GM CSF antibodies. It leads to improvement in symptoms, oxygen saturation and radiological appearance. Lung transplantation has been attempted in patients with congenital PAP.[4]

DISCUSSION

PAP, first described in 1958 by Rosen et al.,[10] is a distinct clinical entity with an estimated prevalence of 0.1 case per 100,000 individuals.[8] This disorder is characterized by intraalveolar accumulation of lipo-proteinaceous material due to defective clearing by the alveolar macrophages. Three distinct subtypes have been recognized: Auto-immune (idiopathic), secondary, and congenital. The auto-immune (idiopathic) form, seen in 90% of the patients, is the most common subtype.[11] Anti-GM-CSF antibodies plays a central role in the pathogenesis of auto-immune (idiopathic) subtype while secondary type is seen in various pulmonary infections, hematological malignancies, and industrial dust exposure.[6]

Chest radiography, a useful screening test, shows a typical perihilar or “batwing” distribution of alveolar opacities. These findings can be confused with those of pulmonary edema, however, absence of cardiomegaly, pleural effusion, Kerley-B lines on chest radiograph usually rules in the favor of PAP. Other less common radiological abnormalities include reticular or reticulonodular shadows, multifocal consolidation, or ground-glassing.[4] The first ever description of “Crazy-paving” pattern on HRCT was in a patient of PAP[12] and has been considered as a hallmark of the disease. HRCT shows areas of patchy alveolar opacification with superimposition of a network of reticulations. These areas of air-space opacification, seen as GGO, are clearly demarcated from the surrounding normal lung parenchyma.[1,4]"Crazy-paving" pattern results from a combination of these reticular networks and GGO. These reticular networks are due to the interlobular, as well as intralobular septal thickening[4] or due to deposition of material in the alveoli at the borders of the acini (periacinar pattern)[3] while the GGO occur due to deposition of PAS-positive material in the alveoli.[4] Together these resemble a pavement lined with irregular shaped stones laid in a polygonal fashion. Apart from the characteristic “Crazy-paving” pattern, other features seen on HRCT include interlobular septal thickening and GGOs without “Crazy-paving” pattern, diffuse bilateral GGOs without septal thickening, consolidation, pulmonary nodules, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and pleural effusion.[13]

BAL has an important supportive role in the diagnosis of PAP. It has a milky appearance due to the presence of lipo-proteinaceous material consisting of phospholipids and surfactant proteins. On staining the BAL fluid, the presence of PAS-positive, eosinophilic, granular, acellular material with occasional enlarged foamy macrophages generally establishes the diagnosis. OLB reveals the deposition of PAS-positive, eosinophilic material within the alveoli without any architectural distortion.[6] Detection of anti-GM-CSF antibodies is an important tool for differentiating autoimmune (idiopathic) form from other subtypes of PAP with a high sensitivity and specificity.

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in India

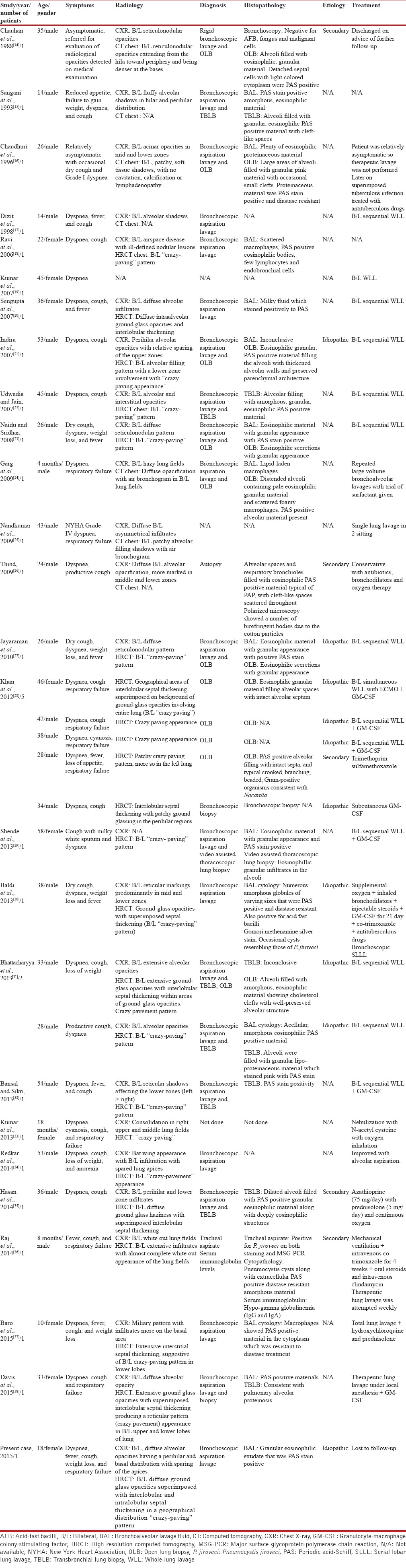

A search of the literature on the subject from India using the PubMed, IndMed databases and Google revealed 25 reports documenting 30 patients of PAP. All 30 documented patients from India were reviewed and are tabulated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pulmonary alveolar proteinoses in India

The first documented report of PAP from India was in a 35-year-old man, a sailor from the armed forces.[14] Of the 30 patients, 22 were males (73%) and the age group varied from 4 months to 54 years in males while in female patients ranged from 18 months to 58 years. There were six patients in the pediatric age group[15,17,24,33,36,37] with four of them being males.[15,17,24,36] Cough and dyspnea were the predominant presenting symptoms seen in almost all patients. Respiratory failure, on presentation, was noted in 9/30 patients (30%).[24,25,27,32,35,37] Our patient too presented with type I respiratory failure. Of the 26 patients[14,16,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] in whom CT chest was performed, HRCT was done in 23.[14,16,18,20,21,22,23,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,37,38] Characteristic “Crazy-paving” pattern was documented in 18 of them.[18,21,22,23,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,37,38] Bilateral “Crazy-paving” was seen in 14/18 patients.[18,21,22,23,27,28,29,30,31,32,34,37,38] Information regarding the distribution of “Crazy-paving” was not available in 4 patients.[27,33] Our patient too had a distinctive bilateral “Crazy-paving” pattern on HRCT. In 16/30 patients information regarding classification either as idiopathic or secondary was not available.[15,16,17,18,19,20,22,23,24,25,29,32,33,34,37,38] The disease was classified as idiopathic in 9/30 patients[21,27,28,30,31] and in five patients as secondary PAP.[14,26,28,35,36] Our patient too was classified as idiopathic.

Diagnosis was established by cytopathological examination and staining of the BAL fluid in 6/30 patients[17,18,20,30,34,37] while in a pediatric patient, tracheal aspirate was used to confirm the diagnosis.[36] In another seven patients, apart from BAL additional transbronchial biopsy was done.[15,22,28,31,32,33,38] OLB was confirmatory in 11/30 patients[14,16,21,23,24,27,28,31] and in one patient video assisted thoracoscopic lung biopsy was done.[29] Autopsy proved the diagnosis in one patient.[26] In three patients information regarding the diagnostic modality was not available.[19,25,33]

WLL as a therapeutic modality was used in 18/30 patients[17,19,20,21,22,23,25,27,28,29,31,32,36,37,38] while serial lobar lung lavage was done in one patient.[30] Of these 18 patients, seven in addition received GM-CSF therapy.[28,29,30,32,37] GM-CSF therapy alone as a treatment modality was used in one patient.[28] In all patients who had undergone WLL, response to therapy was considered to be satisfactory.[17,19,20,21,22,23,25,27,28,29,31,32,36,37,38] In patients who had received GM-CSF therapy in addition to WLL, it could not be ascertained whether the response to therapy was due to WLL or due to GM-CSF.[28,29,30,32,37] The only patient who had received GM-CSF therapy alone showed clinical response but had no radiological improvement.[28] One patient who was symptomatic even after five sessions of WLL showed significant benefit post-GM-CSF therapy.[29] Repeated bronchoscopic lavage was the treatment modality in two patients[24,34] of whom one died.[24] Conservative management was done in five patients[16,26,28,33,35] with mortality seen in one patient.[26] Treatment resulted in remarkable improvement in 25/30 patients.[16,17,19,20,21,22,23,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] In one patient, information regarding the treatment modality was not available[18] while two other patients were lost to follow-up.[14,15] Our patient too was lost to follow-up.

PAP is rare but a distinct clinical entity and presents characteristically with “Crazy-paving” pattern on HRCT. In India, PAP does not appear to be as rare as initially thought and state of the art therapy has been administered with gratifying results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee CH. The crazy-paving sign. Radiology. 2007;243:905–6. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2433041835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maimon N, Heimer D. The crazy-paving pattern on computed tomography. CMAJ. 2010;182:1545. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Wever W, Meersschaert J, Coolen J, Verbeken E, Verschakelen JA. The crazy-paving pattern: A radiological-pathological correlation. Insights Imaging. 2011;2:117–32. doi: 10.1007/s13244-010-0060-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frazier AA, Franks TJ, Cooke EO, Mohammed TL, Pugatch RD, Galvin JR. From the archives of the AFIP: Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Radiographics. 2008;28:883–99. doi: 10.1148/rg.283075219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramirez J, Campbell GD. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Endobronchial treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1965;63:429–41. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-63-3-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borie R, Danel C, Debray MP, Taille C, Dombret MC, Aubier M, et al. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20:98–107. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00001311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seymour JF, Presneill JJ. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: Progress in the first 44 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:215–35. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campo I, Kadija Z, Mariani F, Paracchini E, Rodi G, Mojoli F, et al. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2012;7:4. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ioachimescu OC, Kavuru MS. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Chron Respir Dis. 2006;3:149–59. doi: 10.1191/1479972306cd101rs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen SH, Castleman B, Liebow AA. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 1958;258:1123–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195806052582301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soma P, Ellemdin S, Roche NJ. A crazy cause of dyspnoea: Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Lancet. 2014;384:714. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murch CR, Carr DH. Computed tomography appearances of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Clin Radiol. 1989;40:240–3. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(89)80180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehrian P, Homayounfar N, Karimi MA, Jafarzadeh H. Features of idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in high resolution computed tomography. Pol J Radiol. 2014;79:65–9. doi: 10.12659/PJR.890218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chauhan MS, Jayaswal R, Rajan RS, Chopra RK, Bhalla IP, Tewari SC. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (with review of literature) J Assoc Physicians India. 1988;36:445–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sangani BK, Prabhudesai PP, Tandon SP, Vidyeeswar P, Bijur S, Mahashur AA. Pulmonary alveolar phospholipoproteinosis. Indian Pediatr. 1993;30:917–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaudhuri R, Prabhudesai P, Vaideeswan P, Mahashur AA. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis with pulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc. 1996;43:27–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixit R, Chaudhari LS, Mahashur AA. Anaesthetic management of bilateral alveolar proteinosis for bronchopulmonary lavage. J Postgrad Med. 1998;44:21–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravi R, Mazharunissa A, Meenal JD, Sridharan K. Radiological quiz – Chest. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2006;16:983–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar P, Sengupta S, Rudra A, Maitra G, Ramasubban S, Mukhopadhyay A. Bilateral whole lung lavage in the treatment of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:464–5. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000253593.19982.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sengupta S, Kumar P, Rudra A, Ramasubban S, Mukhopadhyay A. Bilateral whole lung lavage in the treatment of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. J Anesth Clin Pharmacol. 2007;23:79–81. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000253593.19982.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Indira KS, Rajesh V, Darsana V, Ranjit U, John J, Vengadakrishnaraj SP, et al. Whole lung lavage: The salvage therapy for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2007;49:41–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Udwadia ZF, Jain S. Images in clinical medicine. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:e21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm067256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naidu IS, Sridhar Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Apollo Med. 2008;5:61–3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garg G, Sachdev A, Gupta D. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:521–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nandkumar S, Desai M, Butani M, Udwadia Z. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis with respiratory failure-anaesthetic management of whole lung lavage. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53:362–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thind GS. Acute pulmonary alveolar proteinosis due to exposure to cotton dust. Lung India. 2009;26:152–4. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.56355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jayaraman S, Gayathri AR, Senthil Kumar P, Santosham R, Santosham R, Narasimhan R. Whole lung lavage for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Lung India. 2010;27:33–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.59267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan A, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Bal A, Sen I, Yaddanapuddi LN, et al. Experience with treatment of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis from a tertiary care centre in north India. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2012;54:91–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shende RP, Sampat BK, Prabhudesai P, Kulkarni S. Granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor therapy for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2013;61:209–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldi MM, Nair J, Athavale A, Gavali V, Sarkar M, Divate S, et al. Serial lobar lung lavage in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2013;20:333–7. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhattacharyya D, Barthwal MS, Katoch CD, Rohatgi MG, Hasnain S, Rai SP, et al. Primary alveolar proteinosis – A report of two cases. Med J Armed Forces India. 2013;69:90–3. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bansal A, Sikri V. A case of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis treated with whole lung lavage. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2013;17:314–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.120327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar N, Jyoti K, Ranjan S, Varshney AN, Anand A, Anand R. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis a rare disease. Natl J Integr Res Med. 2013;4:106–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Redkar NN, Rawat KJ, Agarwal V, Kolhe P, Shah J. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis an underdiagnosed entity. Indian Pract. 2014;67:574–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasan A, Ram R, Swamy T. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis due to mycophenolate and cyclosporine combination therapy in a renal transplant recipient. Lung India. 2014;31:282–4. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.135782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raj D, Bhutia TD, Mathur S, Kabra SK, Lodha R. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis secondary to Pneumocystis jiroveci infection in an infant with common variable immunodeficiency. Indian J Pediatr. 2014;81:929–31. doi: 10.1007/s12098-013-1027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baro A, Shah I, Chandane P, Khosla I. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in a 10-year-old girl masquerading as tuberculosis. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2015;2015:300–2. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omv039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis KR, Vadakkan DT, Krishnakumar EV, Anas AM. Serial bronchoscopic lung lavage in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis under local anesthesia. Lung India. 2015;32:162–4. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.152636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]