Abstract

Importance

Parent-adolescent sexual communication has received considerable attention as one factor that can positively impact safer sex among youth; however, the evidence linking communication to youth contraceptive and condom use has not been empirically synthesized.

Objective

This meta-analysis examined the effect of parent-adolescent sexual communication on youth safer sex behavior and explored potential moderators of this association.

Data Sources

A systematic search was conducted of studies published through June 2014 using Medline, PsycINFO, and Communication & Mass Media Complete databases and relevant review articles.

Study Selection

Studies were included if they: 1) sampled adolescents (mean sample age≤18); 2) included an adolescent report of sexual communication with parent(s); 3) measured safer sex behavior; and 4) were published in English.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Correlation coefficients (r) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed from studies and meta-analyzed using random-effects models.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was safer sex behavior, including use of contraceptives/birth control or condoms.

Results

Seventy-one independent effects representing over three decades of research on 25,314 adolescents (mean age = 15.1) were synthesized. Across studies, there was a small, significant weighted mean effect (r = .10, [95% CI:0.08–0.13]) linking parent-adolescent sexual communication to safer sex behavior, which was statistically heterogeneous (Q = 203.50, p < .001, I2 = 65.60). Moderation analyses revealed larger effects for communication with girls (r = .12) than boys (r = .04), and among youth who discussed sex with mothers (r = .14) compared to fathers (r = .03). Effects did not differ for contraceptive versus condom use, or among longitudinal versus cross-sectional studies, indicating parent sexual communication had a similar impact across study designs and outcomes. Several methodological issues were identified in the literature; future studies can improve on these by measuring parent-adolescent communication with robust, multi-item measures, clearly specifying the target parent, and applying multi-method longitudinal designs.

Conclusions and Relevance

Sexual communication with parents, particularly mothers, plays a small protective role in adolescent safer sex behavior, and this protective effect is more pronounced for girls than boys. Implications for practice and suggestions for future research on parent-adolescent communication are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Risky sexual behavior among U.S. adolescents is a serious public health problem. Although adolescents make up only a quarter of the sexually active population, they acquire half of all sexually transmitted infections (STIs).1 This amounts to 9 million STIs, including over 8,300 new cases of HIV, each year.1 Additionally, adolescents are at heightened risk of unintended pregnancy.1,2

Parent-adolescent sexual communication has received considerable attention as one factor that could positively impact youth safer sex behavior, including adolescents’ use of contraception and condoms. There are both practical and theoretical reasons why parents may be agents of sexual socialization for young people. From a practical perspective, parents may play a critical role in conveying sexual information and may exert significant influence on adolescents’ sexual attitudes, values, and risk-related beliefs.3,4 Parents may also provide a powerful model of open and honest communication about sexual health issues, which teens may emulate in their own sexual relationships.5

Parents’ influential role on child and adolescent behavior is also widely accepted in developmental and health behavior theory. Bronfenbrenner’s classic Ecological Systems Theory6 of human development suggests that individuals live within a series of nested systems – including the family system – that are dynamic, reciprocal, and can directly and indirectly influence behavior. Grounded in this approach, parent-adolescent sexual communication has increasingly been implicated in health behavior theories that explain youth sexual behavior,7–9 such as the multi-system perspective of adolescent sexual risk behavior.9

Although practical and theoretical considerations suggest that parent communication should be strongly associated with adolescent safer sex behaviors, there is surprising inconsistency in the empirical literature.3,9–12 While several studies have found moderate, positive associations between parent communication and youth contraceptive or condom use,13–16 other studies have found non-significant or even negative effects.17–19 Further, while it is possible that parental communication about sex can be protective for youth, open sexual communication often does not take place. Instead, embarrassment, inaccurate knowledge, or low self-efficacy may prevent some parents from engaging their children in honest and supportive conversations about sex.20 These barriers may explain why nearly a quarter of youth report that they have not discussed sexual topics with a parent,3,21–23 and why even fewer have had meaningful, open conversations about the sexual issues that are critical to their long-term health.

Current Study

The purpose of the current meta-analysis was to synthesize this literature and determine the mean weighted association between parent-adolescent sexual communication and youth contraceptive and condom use. Findings from such an analysis are critical to the growing body of HIV, STI, and pregnancy prevention efforts that target adolescent-parent dyads,24–26 and may be of considerable interest to researchers, educators, family practitioners, and parents themselves. To our knowledge, no such meta-analysis has been published to date, despite a number of narrative reviews and calls for better synthesis of the literature.3,9–12 A first goal of this meta-analysis was to estimate the magnitude of the association between parent communication and adolescent safer sex behavior. We focused on safer sex behavior – i.e., contraceptive and condom use – given the importance of these behaviors to the prevention of HIV, STIs, and unintended pregnancies.27

Given the heterogeneity in this literature, a second goal of the current meta-analysis was to examine several potential moderators of the association between communication and safer sex. Two key moderators examined were adolescent gender and parent gender. Given existing evidence, we expected to find a more robust association between communication and safer sex behavior for girls compared to boys28–31 and for communication with mothers compared to fathers.19,32 Several additional demographic and measurement moderators were also explored. These factors have been examined in prior work and are of direct relevance to family communication interventions. They included: a) adolescent age; b) race/ethnicity; c) study location (U.S./non-U.S. sample); d) study design (cross sectional/longitudinal); e) communication measurement characteristics (source/topic/format/number of items); and f) safer sex outcome (contraceptive use/condoms).

METHOD

Search Strategy

A detailed search was undertaken to locate relevant articles. First, comprehensive searches of PsycINFO, Medline, and Communication & Mass Media Complete databases were conducted through June 2014 using the following combination of key words: (adolescen* OR teen* OR youth OR middle school OR high school) and (communicat* OR discuss* OR negotiat* OR assert* OR talk OR influence) and (contracept* OR birth control OR condom* OR unprotected sex OR sex* risk OR safe* sex). Then, additional studies of potential relevance were located by examining review articles related to sexual communication.3,9–11,33–36

Selection Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: 1) sampled adolescents, defined as a mean sample age of 18 or younger and no participants over 24 years of age;37 2) included an adolescent report of sexual communication with a parent or parents (studies that focused exclusively on parent-reported communication were excluded); 3) measured safer sex behavior, including contraceptives/birth control, condoms, or unprotected sex; 4) reported an association between parent-adolescent communication and safer sex behavior (when bivariate associations were not reported, authors were directly contacted for this information); and 5) were published in English. We excluded papers that used a composite variable for sexual risk taking where it was not possible to tease apart the outcome of contraceptive/condom use (e.g., combining number of sex partners or abstinence along with condom use into a single composite variable38,39). Additionally, in a few instances, there were multiple relevant papers that utilized the same dataset; in these cases, the article with the most complete data relevant to this meta-analysis was included.

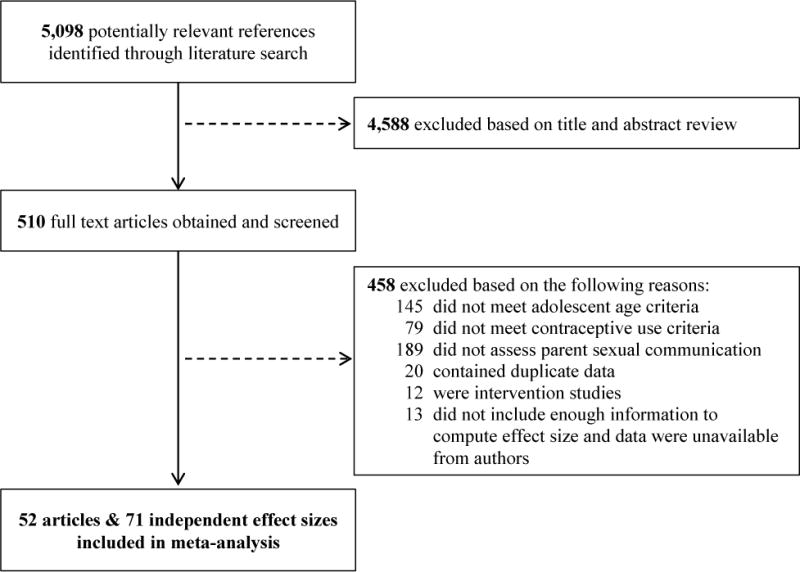

The initial search produced 5,098 scientific references. After a title and abstract review, this was reduced to 510 references. The full text of these 510 articles were then located and reviewed. After applying all selection criteria, the final sample consisted of 52 articles (see Figure 1). Within this final sample, several articles reported results separately for independent samples, including ten studies with analyses separated by gender, two studies separated by race/ethnicity, and one study separated by country (see eTable). Independent effect sizes were calculated for each sample in these cases, resulting in a total of 71 independent effect sizes.40

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram

Most studies reported a single indicator of communication and safer sex behavior. When multiple indicators were reported, several steps were taken to avoid violating the independence assumption that underlies the validity of meta-analyses.41 First, when studies reported contraceptive or condom use with both a frequency score as well as use at first or last intercourse, we utilized the frequency variable to calculate an effect size, as this is more representative of the overall pattern of contraceptive use.42 Next, when studies reported more than one measure of parent-adolescent sexual communication, we analyzed the data in one of two ways. For the majority of analyses, we averaged these communication variables in order to maximize the use of available data and not advantage one measure over another (i.e., overall weighted effect size and comparisons by age, gender, ethnicity, and study location). However, for analyses that examined moderation by communication measurement characteristics, using this averaging approach would have resulted in a loss of specificity of variables, and thus a loss of data. For these analyses, we used a random number generator to randomly select one variable for inclusion.37,41 The same procedure was used to handle the three studies that reported both general contraceptive use and condom use.17,43,44 Specifically, we averaged the effect of communication on these sexual health outcomes for primary analyses, but we used a random number generator to select one outcome variable from each study when we examined the type of outcome (contraceptive use vs. condom use) as a moderator.37,41

Data Extraction

Two authors independently coded the following data from each study: (a) demographic and sample characteristics; (b) sexual communication measurement characteristics (i.e., communication topic, format, source, number of items); and (c) safer sex behavior measurement (i.e., type of safer sex behavior; measurement timeframe). Communication topic was coded into four possible categories, including communication about: 1) contraception/condom use, 2) pregnancy, 3) STIs/HIV, or 4) general sex topics (e.g., discussing “sex”). Communication format was coded into three categories: 1) communication behavior/frequency (i.e., ever/never or indication of sexual communication frequency), 2) communication quality (i.e., perceived comfort, ease, or openness of communicating), and 3) self-efficacy (i.e., perceived confidence in ability to communicate about sex). Finally, communication source was coded based on the parent with whom the adolescent had discussed sex: 1) mother, 2) father, or 3) parent(s). Regarding safer sex behavior, the type of safer sex was coded as: 1) general contraception/birth control, 2) condom use, or 3) unprotected sex (reverse coded to keep direction of effects consistent), and the measurement of safer sex timeframe was coded as: 1) lifetime, 2) past 6 months, 3) past 3 months, 4) first sex, or 5) last sex. The mean percentage agreement between coders across all categories was 96%. Discrepancies between coders were resolved through discussion with the first author.

Calculation of Effect Sizes

A correlation coefficient (r) was used as the indicator of effect size (range= −1.0 to +1.0).45 Effect sizes based on correlations can be interpreted as small (.10), medium (.25), or large (.40).46 When bivariate rs were reported in an article, they were directly extracted. If rs were not reported, then appropriate formulas were used to convert other statistics (e.g., t tests, summary statistics, odds ratios) to approximate rs.45,47 When none of the statistics could be converted to a correlation coefficient, or when only multivariate analyses were reported, study authors were contacted and appropriate raw data were requested. To keep effect sizes consistent and interpretable, values were transposed so that positive correlations always indicated a positive association between communication and safer sex behavior.

Once study characteristics were coded and effect sizes were extracted, a Fisher r to z transformation was performed.45 These values then were weighted by their inverse variance and combined. We used random effects meta-analytic procedures for the primary analysis across all 71 independent effect sizes; this procedure allowed for the possibility of differing variances across studies.41 After analyses were complete, the effect sizes were transformed back to rs for presentation. The Q statistic and I2 were used to examine whether significant heterogeneity existed among effect sizes. Effect sizes for hypothesized moderators were calculated along with their 95% confidence intervals, and those effect sizes were compared using the Qb statistic. For these analyses, mixed effects models were utilized to allow for the possibility of differing variances across subgroups. These models employ random effects assumptions, while stratifying the effect sizes by fixed factors such as gender and study location.41 Analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, Version 2.

RESULTS

Study Characteristics

The eTable provides a summary of the 52 studies and 71 independent effect sizes represented in this meta-analysis, including sample characteristics and moderator variables. Across studies, 25,314 participants were included (weighted mean age=15.2). Of the 71 independent effect sizes, the majority were based on reports of communication with a “parent” or “parents” (k=52); 19 studies specified whether communication was with a mother or father. Similarly, the majority of studies asked about general sexual communication (k=47), with 25 studies assessing more specific topics, such as condom use, HIV/STIs, or pregnancy. Additionally, more than half of studies (k=36) used single-item assessments of sexual communication; the remaining studies measured communication with two to five items (k=17), six to 10 items (k=7), or more than 10 items (k=8). Among all studies, the primary design was cross-sectional (k=64); seven studies utilized a longitudinal design to examine parent-adolescent sexual communication as a predictor of later contraceptive or condom use.4,28,31,44

Magnitude and Direction of Effects

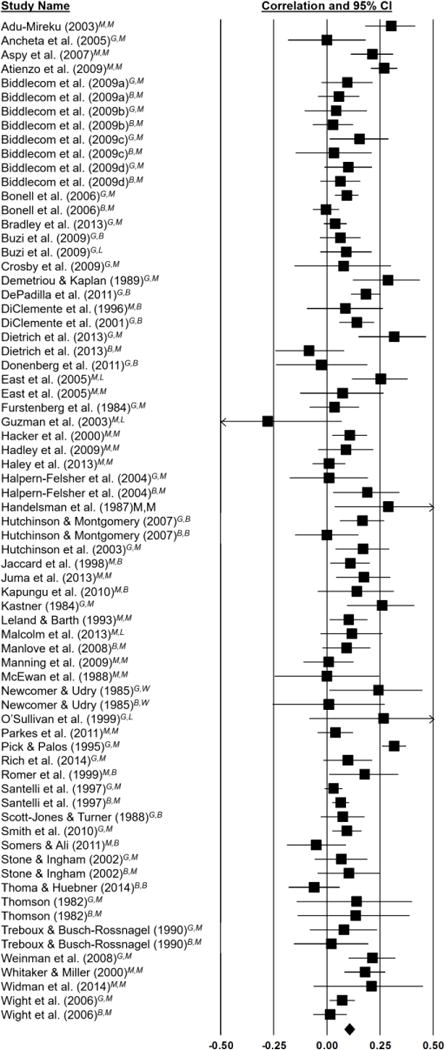

There was a small, significant overall weighted mean effect for the association between parent-adolescent sexual communication and safer sex behavior: r = .10 (95% CI, 0.08–0.13) (see Figure 2). Funnel plots of the effect sizes were symmetrical, and the trim and fill analysis suggested no adjustment to the mean effect size.48 This indicated no evidence of publication bias.

Figure 2.

Forest displaying 71 independent effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals.

Note: Each study is followed by two letters: the first represents the gender of the sample (M=mixed, G=all girls, B=all boys), and the second represents the race/ethnicity of the sample (M=mixed, W=White, B=Black, L=Latino). The diamond indicates the overall weighted mean effect across all studies (r=.10, p<.001).

Heterogeneity and Effect Size Moderators

Although the overall relationship between communication and safer sex was positive and significant, there was considerable heterogeneity among the effect sizes (Q = 203.50, p < .001, I2 = 65.60). Thus, we examined the potential impact of several moderating variables. Studies were only included in moderator analyses if they had sufficient information to be analyzed. For example, when considering gender as a moderator, studies had to sample only boys, only girls, or both genders, but report separate analyses by gender (mixed gender samples that did not separate analyses by gender could not be included, as there was no way to tease apart the relationship between communication and contraceptive use for boys versus girls). The number of studies (k) included in each moderator analysis is indicated in the text below and in Table 1.

Table 1.

Weighted Mean Effect Sizes By Moderator Variables

| Variable | N | k | r | 95% CI | Between groups

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QB | |||||

| Demographic and Study Design Variables

| |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 12,758 | 32 | .12 | [0.09, 0.15]*** | |

| Male | 6,385 | 16 | .04 | [0.02, 0.07]** | |

| Total | 19,143 | 48 | – | – | 13.63*** |

| Study Location | |||||

| U.S. | 16,048 | 49 | .10 | [0.08, 0.12]*** | |

| Non-U.S. | 9,203 | 21 | .11 | [0.06, 0.16]*** | |

| Total | 25,251 | 70 | – | – | 0.06 |

| Age | |||||

| Mean age of sample < 16 | 8,950 | 29 | .11 | [0.08, 0.15]*** | |

| Mean age of sample ≥ 16 | 10,249 | 33 | .10 | [0.06, 0.14]*** | |

| Total | 19,199 | 62 | – | – | 0.14 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Mixed race sample | 20,754 | 51 | .11 | [0.08, 0.13]*** | |

| All White | 125 | 2 | .14 | [−0.10, 0.36] | |

| All Black | 3,758 | 13 | .09 | [0.04, 0.14]*** | |

| All Hispanic | 677 | 5 | .12 | [−0.01, 0.25]+ | |

| Total | 25,314 | 71 | – | – | 0.61 |

| Study Design | |||||

| Cross-sectional | 21,078 | 64 | .11 | [0.08, 0.13]*** | |

| Longitudinal | 4,236 | 7 | .07 | [0.02, 0.11]** | |

| Total | 25,314 | 71 | – | – | 2.31 |

|

| |||||

| Communication Measurement Variables

| |||||

| Communication Sourcea | |||||

| Mother | 2,924 | 12 | .14 | [0.06, 0.21]*** | |

| Father | 2,363 | 7 | .03 | [−0.05, 0.10] | |

| Total | 5,287 | 19 | – | – | 2.58* |

| Communication Topic | |||||

| Contraception/condoms | 3,675 | 16 | .09 | [0.04, 0.15]** | |

| Pregnancy | 989 | 3 | .05 | [−0.02, 0.11] | |

| HIV/STIs | 6,311 | 5 | .10 | [0.04, 0.16]** | |

| General topics | 14,339 | 47 | .11 | [0.07, 0.14]*** | |

| Total | 25,314 | 71 | – | – | 2.65 |

| Communication Format | |||||

| Behavior/frequency | 20,495 | 53 | .10 | [0.07, 0.13]*** | |

| Quality | 4,166 | 14 | .10 | [0.06, 0.14]*** | |

| Self-efficacy | 384 | 3 | .17 | [0.01, 0.32]* | |

| Total | 25,045 | 70 | – | – | 0.78 |

| Number of Items Used to Assess Communication | |||||

| 1 item | 16,442 | 36 | .09 | [0.06, 0.11]*** | |

| 2–5 items | 4,206 | 17 | .12 | [0.07, 0.16]*** | |

| 6–10 items | 1,983 | 7 | .12 | [0.00, 0.23]* | |

| 11 or more items | 1,366 | 8 | .07 | [−0.01, 0.15]+ | |

| Total | 23,997 | 68 | – | – | 1.85 |

|

| |||||

| Safer Sex Behavior Variables

| |||||

| Type of Safer Sex Behavior | |||||

| Contraception/birth control | 14,910 | 35 | .09 | [0.06, 0.13]*** | |

| Condom use | 8,860 | 29 | .12 | [0.08, 0.16]*** | |

| Unprotected sex | 1,544 | 7 | .06 | [−0.03, 0.15] | |

| Total | 25,314 | 71 | – | – | 2.22 |

| Safer Sex Behavior Timeframe | |||||

| Lifetime | 7,211 | 29 | .10 | [0.05, 0.14]*** | |

| Past 6 months | 1,048 | 5 | .07 | [−0.06, 0.20] | |

| Past 3 months | 1,310 | 6 | .13 | [0.08, 0.19]*** | |

| First sex | 3,876 | 6 | .09 | [−0.00, 0.18]+ | |

| Last sex | 10,308 | 21 | .09 | [0.06, 0.13]*** | |

| Total | 23,753 | 67 | – | – | 1.77 |

Note. N = sample size; k = number of studies (when groups do not total 71, it is because one or more studies were missing the appropriate information to be included in that analysis); r = weighted mean effect size; CI = confidence interval. Mixed effects models are presented for moderator analyses.

Moderator analyses by communication source compared mother to father communication; the mean weighted effect of communication with “parent(s)” was r = .10, p < .001 across studies.

p<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

First, we examined moderators related to participant demographics and study design. As shown in Table 1, there was significant moderation by gender (k=48), with a stronger association between parent-adolescent communication and safer sexual behaviors with girls (r = .12) compared to boys (r = .04). The strength of this association was not found to differ significantly by adolescents’ age (k=62) or ethnicity (k=71), or by the location of study (k=70). Additionally, effect sizes did not differ significantly when comparing longitudinal versus cross sectional study designs (k=71).

Next, several aspects of sexual communication were examined as potential moderators (Table 1). Among studies that specified the source of communication (i.e., mother versus father; k=19), the association between sexual communication and youth safer sex behaviors was significantly stronger for adolescents who had discussed sexual topics with their mothers (r = .14) versus fathers (r = .03). In fact, communication with fathers was not significantly associated with adolescent safer sex behavior across studies (r = .03; p = .46). The strength of the association between communication and safer sex did not differ significantly based on the topic of conversation (k=71), the format of communication measurement (k=70), or the number of items used to assess communication (k=68).

Finally, two factors specific to the outcome of safer sex behavior were examined as moderators, including the type and timing of safer sex examined in each study. As shown at the bottom of Table 1, effects did not differ based on the safer sex outcomes (k=71), with similar significant associations found for both contraceptive use (r = .09) and condom use (r = .12). Effects were also consistent across the measurement timeframes (i.e., lifetime, past 6 months, past 3 months, first sex, and last sex; k=67).

DISCUSSION

Pooling data from three decades of research with over 25,000 adolescents, the current meta-analysis found a significant positive association between parent-adolescent sexual communication and youth safer sex behavior. This effect was robust across condom and contraceptive use outcomes, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, and among both younger and older samples. Importantly, the strength of this association was moderated by adolescent and parent gender, with stronger effects for girls than boys and for communication with mothers than fathers.

Importantly, the relationship between parent communication and adolescents’ contraceptive and condom use was significantly stronger for girls than for boys. This is consistent with past work showing that parents communicate more frequently with girls and are also more likely to stress the negative consequences of sexual activity when discussing sex with daughters compared to sons.21,23,30,49–51 If parents wish to exert a stronger influence on their sons’ safer sex practices, they may need additional training to change the frequency, content, and/or tone of the messages surrounding sex that they communicate to boys.

The association between communication and safer sex was also moderated by the gender of the parent. Specifically, adolescent communication with mothers was positively associated with use of protection, but there was not a significant association between father-adolescent communication and safer sex behavior. Across a variety of circumstances, men and boys are less verbally expressive, open to self-disclosure, and attuned to emotional and relational cues compared to girls and women.52 This difficulty in sharing emotional experiences or discussing potentially embarrassing relational topics may inhibit some boys’ and fathers’ abilities to have open and intimate conversations about sexual health. It would be ideal to examine whether specific factors related to fathers’ communication might amplify the impact of communication on adolescents’ safer sex practices – such as how often fathers are communicating with their sons or daughters and the specific content or comfort level of these conversations; unfortunately, there are currently too few studies of father communication to examine these fundamental questions. This remains a ripe area for future inquiry.

Taken together, our results confirm that across more than 50 studies, parent-adolescent sexual communication is positively associated with adolescents’ contraceptive and condom use practices, regardless of communication topic or format. However, this effect explained a relatively small proportion of the variance in safer sex behavior. Thus, results underscore the importance of understanding parent communication – likely a more distal predictor – in the context of more proximal factors that contribute to sexual decision-making. Building on preliminary models of parent-adolescent communication,7,8,10 future theoretical and empirical work should examine how parent communication impacts individual-level factors (e.g., attitudes and self-efficacy53) as well as couple-level factors (e.g., partner communication and negotiation processes37,54), and how these and other factors may mediate the association between communication and safer sex. In line with family systems theory,55 it is also possible that alternative parenting constructs, such as parent-adolescent relationship quality, parental monitoring, or the marital relationship itself, may interact with communication to predict youth sexual behavior.39 Future work will benefit from in-depth analyses of the role that parental communication may play in adolescent sexual decision-making within these multiple domains of influence.

Methodological Considerations

Several methodological issues were identified in this literature review that may have obscured the detection of more robust effects and are worthy of future research attention. In particular, addressing these study design issues may elucidate why several expected communication measurement characteristics (i.e., topic and format)37,54 did not emerge as significant moderators of the association between communication and behavior.

First, many studies assessed sexual communication with unspecified “parent(s).” In these cases, it was not possible to know if youth were reporting communication with mothers, fathers, or both parents. Given the current moderator findings, as well as previous research demonstrating more frequent communication with mothers on sexual issues than with fathers,56 the overall association may be mostly driven by communication with mothers. Additional research is needed to better understand this issue.

Second, more than half of studies used single-item assessments of parent-adolescent communication. This is not ideal from a measurement perspective, as single-item assessments are unlikely to capture the full nuance and complexity of the communication process. It is clear that the quality and timing of communication can have important implications for youth sexual decision-making.58 Given that many parents misjudge when their adolescents begin sexual activity, communication about sex may begin after sexual initiation and limit the potential impact of these discussions.22,59 To further our understanding of communication among adolescents and their parents, we need to utilize not only brief measures of the content or frequency of communication, but also in-depth measures of the timing, tone, and style of these sexual discussions.10,36,57 This may require mixed methods longitudinal studies in which quantitative reports are collected alongside qualitative interviews, perhaps utilizing ecological momentary assessments to capture communication soon after it occurs. It would also be useful to obtain reports of communication from both adolescents and their parents, to identify discrepancies in the frequency or quality of communication that each individual reports.13

Finally, of the 71 independent effects identified, only seven utilized longitudinal designs. While there were not significant differences in the effect sizes drawn from cross-sectional versus longitudinal studies, additional work should utilize multi-wave longitudinal designs to tease out the timing of communication and contraceptive behavior.

Implications for Intervention Efforts

Results of this study confirm that parent-adolescent sexual communication is a protective factor for youth, and a focus on communication remains justified in future intervention efforts. Because conversations about sexuality can be uncomfortable or embarrassing for both parents and adolescents, educational efforts may be most successful if they provide clear, practical instruction and help parents optimize the timing and language used in their approach.25 In addition to formal intervention programs with parents, physicians and other health care providers who interact with parents and youth are in a unique position to encourage healthy communication about sexual topics. Specifically, physicians can have clear and honest conversations about sexual health issues in professional settings to model sexual communication skills,61 perhaps helping families initiate these conversations. They can also urge both parents and adolescents to have such conversations at home, as well as provide resources to parents on when and how to discuss sensitive sexual health topics.

Conclusions

This study fills a critical gap in the literature by meta-analyzing the association between parent-adolescent sexual communication and youth safer sex behavior. Across more than three decades of research and 25,000 adolescents, the current meta-analysis suggests that communication with parents – particularly among mothers and girls – has a small protective effect on adolescent contraceptive and condom use. Further research utilizing more sophisticated assessments, longitudinal designs, and mixed methods approaches are needed to advance this literature and to better understand the impact parents have on the health of their adolescents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported in part by the following National Institutes of Health grants: R00 HD075654, K24 HD069204, P30 AI50410, and UL1 TR001111. This work was also supported in part by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1144081 awarded to Jacqueline Nesi.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: These funding organizations provided support for the design and conduct of the study, and the collection, management, and analysis of the data.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Each author participated fully in the execution of this study. Dr. Widman conceptualized the study, conducted primary analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Widman had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Noar conceptualized the study, supervised analyses, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Ms. Choukas-Bradley and Ms. Nesi screened articles for eligibility, coded all articles, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Ms. Garrett screened articles for eligibility, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Disclaimer: The content, interpretations, and conclusions of this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Science Foundation.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have no financial relationships or conflicts of interest related to this study to disclose.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual risk behavior: HIV, STD, & teen pregnancy prevention. 2015 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/sexualbehaviors.

- 2.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: Preliminary data for 2009. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2010;59 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiIorio C, Pluhar E, Belcher L. Parent-child communication about sexuality. J HIV/AIDS Prevention Educ Adolesc Child. 2003;5:7–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutchinson MK, Jemmott JB, Sweet Jemmott L, Braverman P, Fong GT. The role of mother–daughter sexual risk communication in reducing sexual risk behaviors among urban adolescent females: A prospective study. J Adolescent Health. 2003;33:98–107. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitaker DJ, Miller KS, May DC, Levin ML. Teenage partners’ communication about sexual risk and condom use: The importance of parent-teenager discussions. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31:117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bronfenbrenner U. Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. Am Psychol. 1979;34:844–850. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beadnell B, Wilsdon A, Wells EA, Morison DM, Gillmore MR, Hoppe M. Intrapersonal and interpersonal factors influencing adolescents’ decisions about having sex: A test of sufficiency of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J Applied Social Psychol. 2007;37:2840–2876. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutchinson MK, Wood EB. Reconceptualizing adolescent sexual risk in a parent-based expansion of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J Nursing Scholarship. 2007;39:141–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotchick BA, Shaffer A, Forehand R, Miller KS. Adolescent sexual risk behavior: A multi-system perspective. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21:493–519. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaccard J, Dodge T, Dittus P. Parent-adolescent communication about sex and birth control: A conceptual framework. New Dir Child Adolescent Dev. 2002;97:9–41. doi: 10.1002/cd.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Lee J, et al. Paternal influences on adolescent sexual risk behaviors: A structured literature review. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e1313–1325. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller KS, Kotchick BA, Dorsey S, Forehand R, Ham AY. Family communication about sex: What are parents saying and are their adolescents listening? Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:218–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aspy CB, Vesely SK, Oman RF, Rodine S, Marshall L, McLeroy K. Parental communication and youth sexual behaviour. J Adolesc. 2007;30:449–466. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DePadilla L, Windle M, Wingood G, Cooper H, DiClemente R. Condom use among young women: Modeling the theory of gender and power. Health Psychol. 2011;30:310–319. doi: 10.1037/a0022871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pick S, Palos PA. Impact of the family on the sex lives of adolescents. Adolescence. 1995;30:667–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitaker DJ, Miller KS. Parent-adolescent discussions about sex and condoms: Impact on peer influences of sexual risk behavior. J Adolescent Res. 2000;15:251–273. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haley T, Puskar K, Terhorst L, Terry MA, Charron-Prochownik D. Condom use among sexually active rural high school adolescents personal, environmental, and behavioral predictors. J School Nursing. 2013;29:212–224. doi: 10.1177/1059840512461282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manning WD, Flanigan CM, Giordano PC, Longmore MA. Relationship dynamics and consistency of condom use among adolescents. Perspect Sex Repro H. 2009;41:181–190. doi: 10.1363/4118109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Somers CL, Ali WF. The role of parents in early adolescent sexual risk-taking behavior. Open Psychol J. 2011;4:88–95. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hockenberry-Eaton EM, Richman MJ, DiIorio C, Rivero T, Maibach E. Mother and adolescent knowledge of sexual development: The effects of gender, age, and sexual experience. Adolescence. 1996;31:35–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adu-Mireku S. Family communication about HIV/AIDS and sexual behaviour among senior secondary school students in Accra, Ghana. African Health Sciences. 2003;3:7–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller KS, Levin ML, Whitaker DJ, Xu X. Patterns of condom use among adolescents: The impact of mother-adolescent communication. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1542–1544. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Helms SW, Golin CE, Prinstein MP. Sexual communication between early adolescents and their dating partners, parents, and best friends. J Sex Res. 2014;51:731–741. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.843148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown LK, Hadley W, Donenberg GR, et al. Project STYLE: A multisite RCT for HIV prevention among youths in mental health treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:338–344. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuster MA, Corona R, Elliott MN, et al. Evaluation of Talking Parents, Healthy Teens, a new worksite based parenting programme to promote parent-adolescent communication about sexual health: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 2008;337:a308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39609.657581.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akers AY, Holland CL, Bost J. Interventions to improve parental communication about sex: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:494–510. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noar SM, Zimmerman RS. Safe sex. In: Reis HT, Sprecher S, editors. Encyclopedia of human relationships. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. pp. 1395–1397. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonell C, Allen E, Strange V, et al. Influence of family type and parenting behaviours on teenage sexual behaviour and conceptions. J Epidemiology Community Health. 2006;60:502–506. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.042838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dietrich J, Sikkema K, Otwombe KN, et al. Multiple levels of influence in predicting sexual activity and condom use among adolescents in Soweto, Johannesburg, South Africa. J HIV/AIDS & Social Serv. 2013;12:404–423. doi: 10.1080/15381501.2013.819312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hutchinson MK, Montgomery AJ. Parent communication and sexual risk among African Americans. Western J Nursing Research. 2007;29:691–707. doi: 10.1177/0193945906297374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newcomer SF, Udry JR. Parent-child communication and adolescent sexual behavior. Fam Plann Perspect. 1985;17:169–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomson E. Socialization for sexual and contraceptive behavior: Moral absolutes versus relative consequences. Youth & Society. 1982;14:103–128. doi: 10.1177/0044118x82014001005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buhi ER, Goodson P. Predictors of adolescent sexual behavior and intention: A theory-guided systematic review. J Adolescent Health. 2007;40:4–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Short MB, Yates JK, Biro F, Rosenthal SL. Parents and partners: Enhancing participation in contraception use. J Pediatr Adol Gynec. 2005;18:379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Commendador KA. Parental influences on adolescent decision making and contraceptive use. Pediatric Nursing. 2010;36:147–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lefkowitz ES, Stoppa TM. Positive sexual communication and socialization in the parent-adolescent context. New Dir Child Adolescent Dev. 2006;112:39–56. doi: 10.1002/cd.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Widman L, Noar SM, Choukas-Bradley S, Francis DB. Adolescent sexual health communication and condom use: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2014;33:1113–1124. doi: 10.1037/hea0000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holtzman D, Rubinson R. Parent and peer communication effects on AIDS-related behaviors among U.S. high school students. Fam Plann Perspect. 1995;27:235–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huebner AJ, Howell LW. Examining the relationship between adolescent sexual risk-taking and perceptions of monitoring, communication, and parenting styles. J Adolescent Health. 2003;33:71–78. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noar SM, Cole C, Carlyle K. Condom use measurement in 56 studies of sexual risk behavior: review and recommendations. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35:327–345. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby R, Cobb BK, Harrington K, Davies SL. Parent-adolescent communication and sexual risk behaviors among African American adolescent females. J Pediatrics. 2001;139:407–412. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.117075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wight D, Williamson L, Henderson M. Parental influences on young people’s sexual behaviour: A longitudinal analysis. J Adolescence. 2006;29:473–494. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonett DG. Transforming odds ratios into correlations for meta-analytic research. Am Psychol. 2007;62:254–255. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Darling CA, Hicks MW. Parental influence on adolescent sexuality: Implications for parents as educators. J Youth Adolesc. 1982;11:231–245. doi: 10.1007/BF01537469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kapungu CT, Baptiste D, Holmbeck G, et al. Beyond the “Birds and the Bees”: Gender differences in sex-related communication among urban African-American adolescents. Fam Process. 2010;49:251–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Sullivan LF, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Watkins BX. Mother-daughter communication about sex among urban African American and Latino families. J Adolescent Res. 2001;16:269–292. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brizendine L, B A. Are gender differences in communication biologically determined? In: Slife B, editor. Clashing views on psychological issues. 16th. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2010. pp. 72–88. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noar SM, Carlyle K, Cole C. Why communication is crucial: Meta-analysis of the relationship between safer sexual communication and condom use. J Health Comm. 2006;11:365–390. doi: 10.1080/10810730600671862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nichols M, Schwartz R. Family therapy: Concepts and methods. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 56.DiIorio C, Kelley M, Hockenberry-Eaton M. Communication about sexual issues: Mothers, fathers, and friends. J Adolescent Health. 1999;24:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martino SC, Elliott MN, Corona R, Kanouse DE, Schuster MA. Beyond the “big talk”: The roles of breadth and repetition in parent-adolescent communication about sexual topics. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e612–618. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mueller KE, Powers WG. Parent-child sexual discussion: Perceived communicator style and subsequent behavior. Adolescence. 1990;25:469–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beckett MK, Elliott MN, Martino S, et al. Timing of parent and child communication about sexuality relative to children’s sexual behaviors. Pediatrics. 2010;125:34–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hadley W, Stewart A, Hunter HL, et al. Reliability and validity of the Dyadic Observed Communication Scale (DOCS) J Child Fam Studies. 2013;22:279–287. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9577-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller KS, Wyckoff SC, Lin CY, Whitaker DJ, Sukalac T, Fowler MG. Pediatricians’ role and practices regarding provision of guidance about sexual risk reduction to parents. J Prim Prev. 2008;29:279–291. doi: 10.1007/s10935-008-0137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.