Abstract

The objective of this article is to describe the key areas of consideration for global/international advanced pharmacy practice experience (G/I APPE) preceptors, students and learning objectives. At the 2013 Annual Meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP), the GPE SIG prepared and presented an initial report on the G/IAPPE initiatives. Round table discussions were conducted at the 2014 AACP Annual Meeting to document GPE SIG member input on key areas in the report. Literature search of PubMed, Google Scholar and EMBASE with keywords was conducted to expand this report. In this paper, considerations related to preceptors and students and learning outcomes are described. Preceptors for G/I APPEs may vary based on the learning outcomes of the experience. Student learning outcomes for G/I APPEs may vary based on the type of experiential site. Recommendations and future directions for development of G/IAPPEs are presented. Development of a successful G/I APPE requires significant planning and consideration of appropriate qualifications for preceptors and students.

Keywords: global, international, experiential education, preceptors, students, learning objectives

INTRODUCTION

This paper on global/international advanced pharmacy practice experiences (G/I APPEs) builds on Alsharif et al’s article, which addresses considerations related to the home/host country and host site/institution.1 Both papers focus on the report submitted by the Global Pharmacy Education (GPE) SIG to address the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Strategic Plan Goal 1.4.1. Alsharif et al’s article reviews the process of development for the reports in further detal.1 The AACP Board of Directors expressed interest in having the report transformed into a formal publication for the benefit of academy members. The focus of this article is on considerations related to G/I APPE preceptors, students, and student learning outcomes for these experiences.

METHODS

This paper used multiple iterative methodologies. The preliminary findings and recommendations of the GPE Taskforce were reviewed at the 2014 AACP Annual Meeting. Round table discussions focused on five key areas of G/I APPEs including home/host country, home/host site, home/host institution, preceptor and student considerations, and learning outcomes. A facilitator was assigned to each table to lead discussion and document input from approximately 40 pharmacy educators on the key areas. Input from these sessions was compiled, analyzed, and incorporated into this article’s recommendations. Once this feedback was received, each section of the report was further investigated using a comprehensive literature review of the PubMed, Google Scholar, EMBASE databases using the following keywords as search terms: international, global health, rotations, training, APPE, mission trip, learning, objectives, outcomes, and students. These terms were searched in conjunction with the following terms to limit results to professional student training: pharmacy, nursing, physical therapy, social work, public health, and medicine. Guidelines from allied health professional organizations, Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Standards, and other Internet sources were included in the review. The results of the literature review were combined with the results from the round table discussions and the task force summary document.

PRECEPTOR CONSIDERATIONS

Student learning on a G/I APPE is the primary responsibility of the preceptor. Appropriate selection of preceptors for a G/I APPE requires that they meet ACPE qualifications and possess characteristics that reflect best standards in pharmacy practice. Appropriate assessment of the preceptors must be conducted, and preceptor development should be implemented to ensure they continue to meet G/I APPE standards. This section reviews recommended preceptors’ qualifications, preceptor characteristics and responsibilities, preceptor development, and assessment of preceptors. These considerations apply to US-based preceptors accompanying US students traveling abroad, international preceptors or nonpharmacist preceptors who may serve as preceptors to US students in the host country, and US preceptors to international students.

Preceptor Qualifications

As pharmacy programs seek to expand G/I APPE opportunities for students, the ability of preceptors to direct desired learning experiences and meet ACPE criteria must be carefully evaluated. However, pharmacy programs should not become overly prescriptive regarding G/I APPE preceptor qualifications, which may result in missed learning opportunities for their students. Accreditation Standards from ACPE provide criteria for the selection of preceptors for both introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs) and APPEs. In the ACPE Standards, criteria for the qualifications of preceptors are specified in key element 21.1, which states, “Experiential education preceptors must be qualified licensed pharmacists unless a compelling case can be made for alternative practice credentials.”2 Thus, the ACPE Standards allow flexibility to pharmacy programs in identifying the appropriate preceptors for G/I APPEs in these alternative practice models.

Global/international APPEs represent alternative practice settings where a US preceptor may oversee the G/I APPE with support from onsite international preceptors or from a nonpharmacist preceptor. Nonpharmacists may serve as valuable global preceptors to student pharmacists as high quality global health learning experiences may occur in a variety of settings with other health care practitioners. Compellingly, the Global Health Education Consortium notes that “the most valuable information may come from those without any formal, global health training, but instead have the volume of knowledge and expertise that comes from living in a community and understanding its dynamics, strengths, weaknesses, resources, and challenges.”3 For example, a student may work closely with a nongovernmental organization (NGO) the primary purpose of which is not focused on drug therapy, but still provides opportunities for public health and population-based care (eg, primary sanitation, public health initiatives).4

In general, when a program uses an international preceptor or nonpharmacist preceptor, the expectations should be similar to that of a US preceptor. All preceptors should receive an orientation to the school’s mission, goals, and values. The preceptor should have an understanding of the pharmacy program’s curriculum, teaching methodologies, specific objectives for the APPE, student performance assessment, and grading systems. In addition, the preceptor should receive training on assessment of students’ prepractice experience knowledge relative to the practice experience’s objectives, so the preceptor can tailor the practice experience to maximize the educational experience and ensure appropriate student interaction with patients, caregivers, and other health professionals. An international preceptor should be aware of the G/I APPE goals and objectives and seek to meet them. If preceptors are practicing pharmacists, they must comply with local laws and regulations including licensure and certification. Given the logistical challenges, orientation of international preceptors does not need to be completed in the United States or in person, and use of alternative media and technology (eg, Skype, GoToMeeting) is encouraged.

It is important to consider variability in the preceptor’s skills and training as a result of pharmacy education not being standardized worldwide. According to the FIPEd Global Education Report, degree titles and lengths of education vary, which suggests different content and education provision models among countries and regions.5 As a result of this variance, it is a challenge to establish standard credentialing criteria for international preceptors. Schools of pharmacy should utilize and adapt processes to document individual preceptor licensure, and they should be validated and documented by the experiential education office. Knowledgeable onsite preceptors and a close relationship with a faculty preceptor or administrator from the US institution’s experiential education department are essential for G/I APPE students. The onsite preceptor facilitates learning experiences and provides support at the experiential site and works alongside a faculty preceptor or administrator who may serve as the preceptor of record for the home institution.6 The support system for international preceptors should be specified in a memorandum of understanding, which is critical to the successful implementation of a G/I APPE.1

Preceptor Responsibilities and Characteristics

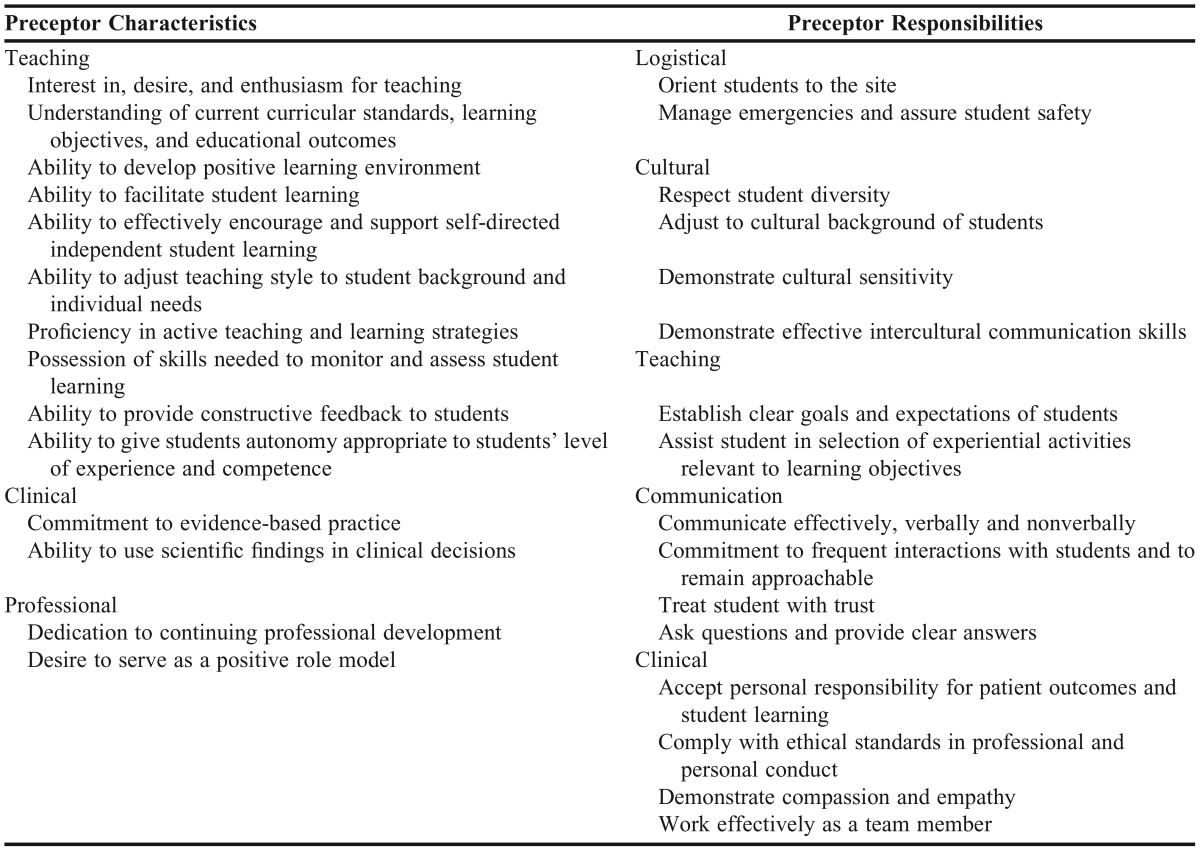

The 2004 AACP Professional Affairs Committee (PAC) report provided guidance on preceptor characteristics thought to be conducive to effective learning. Specifically, a preceptor should be approachable and available to the student for interaction and discussion, demonstrate trust and respect for the student in interactions, and demonstrate interest and enthusiasm in teaching. In addition, the report stressed that an effective preceptor explains the decision-making process to the student, asks questions that promote learning, stimulates the student to learn independently, allows autonomy appropriate to the student’s level of experience and competence, and regularly provides meaningful positive and negative feedback to the student in regular and timely manner.7

The AACP Academic-Practice Partnership Initiative (APPI) on preceptor-specific criteria of excellence describes six criteria necessary for effective precepting: possesses leadership/management skills; embodies a practice philosophy; demonstrates being a role model practitioner; is an effective, organized, and enthusiastic teacher; encourages self-directed learning with constructive feedback; and has well developed interpersonal communication skills.8 Recommended characteristics and responsibilities of preceptors engaged in G/I pharmacy experiences are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Preceptor Characteristics and Responsibilities

Regardless of preceptor type (US, international, nonpharmacist), at a minimum, G/I APPE preceptors should be able to orient the student to the practice experience site, assist in selection of activities with respect to practice experience objectives, student goals, and level of expertise, outline parameters of responsibility for activities, special projects, and timelines, assess the student’s progress, communicate regularly with the experiential learning coordinator on the student’s performance (especially if performance is unsatisfactory) and concerns about the student’s progress, share information with the pharmacy program, and complete an evaluation of the student’s performance after appropriate discussion with the student. Additionally, the importance of intercultural communication (ie, the sending and receiving of languages across cultures and a negotiated understanding of meaning in human experiences across societal systems and societies) must be considered by all G/I APPE preceptors. In this context, considerations of differences in educational hierarchy norms and gender roles must be discussed with preceptors to assure a rewarding experience for both preceptor and student.9,10

Additionally, key characteristics are important to consider in the scenario of US preceptors for international students such as demonstrated cultural sensitivity and ideally experience working with culturally diverse students or in an international setting.11 Cultural sensitivity of the preceptor allows the delivery of educational and health care services in a respectful and responsive manner to diverse patient and student populations.12 Awareness or sensitivity of the preceptor on cultural issues that influence the international students’ learning styles and philosophies of practice is critical to align the expectations of US preceptors and international students. The development of cultural sensitivity enables better understanding of contexts, perceptions, beliefs, and religious constructs from which the learner may perceive information and practice in the United States.13,14 Coupled with exhibiting cultural humility, cultural sensitivity ensures preceptors have an egoless attitude in their interactions with patients, other health care professionals, and the public at large. It also ensures preceptors recognize the limitations of their scope of practice and acknowledge the need to seek the opinion of other health care professionals. 15

As discussed by Campinah-Bacote, cultural competency is a continuum, and thus, it may be unrealistic to expect all practicing pharmacists to be culturally competent unless they have developed attitudes, skills, and behaviors through interactions, travel, and/or encounters that promote cultural awareness or progression towards cultural competence.11,16 This is expected to change with the integration of the update to the Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) Outcomes into pharmacy curricula, where the need for cultural sensitivity in patient care is recommended in Domain 3.17 Li proposes a 3-stage approach to improve teachers’ interactions with culturally diverse students, beginning with cultural reconciliation, cultural translation, and cultural transformation.18 Cultural reconciliation begins with teachers understanding their own cultural identity in relation to others, often resulting in a more empathetic understanding of others’ cultures. In the cultural translation stage, teachers form skills to incorporate multiple cultural perspectives into student learning and adjust teaching styles for different learning styles. This skill is particularly important when precepting international students in the United States who may have different views on the role of the preceptor. For instance, students may view questioning the preceptor as disrespectful whereas the preceptor may believe students are not engaged with learning. Cultural transformation occurs when the teacher helps students develop the ability to merge different cultural traditions and values. There is a transition from cultural dominance to understanding alternative versions of the self-other relationship. This strategy may be effective for providing preceptor development in the area of cultural sensitivity.18 Preceptor sensitivity to students’ inherent cultures, beliefs, and religious practices is needed for effective learning and avoids culturally inadequate statements and expectations.

Adequate qualifications and diverse characteristics of preceptors to international students are essential because preceptors serve as role models demonstrating professionalism, confidence in clinical skills, compassion, and cultural sensitivity.19 While hosting international students can be challenging, it has great value and can be mutually beneficial to students and faculty members.20

Preceptor Development and Assessment

Elements 21.3 and 21.4 in the ACPE Standards focus on the responsibilities of pharmacy programs to foster preceptor development including orientation “…to the program’s mission, the specific learning expectations for the experience outlined in the syllabus, and effective performance evaluation techniques…”2 The program must foster the professional development of its preceptors commensurate with their educational responsibilities in the program. Schools of pharmacy are also required to “…solicit the active involvement of preceptors in the continuous quality improvement of the educational program, especially the experiential component…”2

Pharmacy programs are encouraged to develop formal mechanisms through which preceptors may officially affiliate with the institution. These should include appropriate academic appointments based on preceptors’ credentials and the types of appointments offered by the particular school. Preceptors should be provided with educational resources, as appropriate, to enhance their professional development and ability to mentor and evaluate students.

Prepractice experience discussions and information exchange should occur between preceptors and the pharmacy program to ensure students are provided with a quality experience and complete learning objectives. This may include travel to the site or use of technology such as Skype by members of the experiential education office prior to the arrival of G/I APPE students. Evaluation of the experiential site and preceptor is necessary before sending students there. An established process should be set by the school to ensure continual assessment of the preceptor’s ability to meet the objectives of the practice experience over time. Students should have direct communication access to the sending institution’s experiential education office in the event of unanticipated changes in the preceptor.

Once the G/I APPE experience concludes, the experiential education office should obtain confidential student evaluations of preceptors’ qualities and performance. If the methods of assessment and reporting promote development of the students’ ability to offer constructive criticism in a manner appropriate to interprofessional relationships. Student evaluations should also cover the preceptor’s ability to facilitate learning, communication skills, quality as a professional role model, and effectiveness related to the educational goals of the APPE. A variety of methods to assess preceptor effectiveness can be used such as a review committee consisting of practitioners, faculty members, and students, surveys of faculty members and students, and onsite interviews or visits. This feedback, with considerations of intercultural communication, can be essential to fostering a continued positive experience for the host preceptor and future students.10 Members of the experiential education office visiting G/I APPE sites is ideal but not always possible considering time and expense. If a site visit by a member of the experiential education team is not possible, it can be delegated to faculty members who travel to the site. It is also possible to conduct an assessment of the preceptor or site via phone or other virtual methods.

Recommendations for Preceptor Considerations

Schools of pharmacy should be flexible in selecting preceptors for G/I APPEs and recognize that non-pharmacist and international based preceptors may be used. Descriptions of preceptor qualifications should include language that can be applied to nonpharmacist or international preceptors. Preceptors should be provided with documentation of students’ pre-rotation knowledge and experience relative to rotation objectives. Preceptors should be given the rotation objectives and student learning objectives prior to the arrival of students and be provided sufficient time to organize the students experience to ensure the objectives are met. Schools of pharmacy should provide preceptors with educational resources to enhance their professional development and ability to precept and evaluate students. Schools of pharmacy should maintain adequate and regular communication with the students and preceptors during the G/I APPE. Lastly, programs should consider methods of increasing preceptor recognition, particularly nonfaculty or international preceptors, through awards or adjunct appointments if able.

Preceptor responsibilities for G/I APPEs should include an understanding of the respective pharmacy program’s mission, values, and goals. During the G/I APPE experience, they must maintain communication with the home institution. Preceptors should complete cultural sensitivity training and demonstrate that they have developed the attitudes, skills, and behaviors to be sensitive to intercultural communication differences and students’ inherent cultures, including but not limited to, gender roles, educational hierarchy norms, beliefs, and religious practices. They should demonstrate a desire and aptitude for teaching, be positive role models for students, and effectively facilitate student learning. Additionally, preceptors should engage in professional growth and life-long learning through participation in professional organizations and continuing education programs. This may also be accomplished through participation in preceptor training and development activities.

The GPE SIG or AACP can further advance the recommendations for preceptor considerations through administering a survey of experiential program directors and faculty members who precept students on G/I APPEs to determine what should be documented for qualifications of an international preceptor. Additionally, they should work to develop ways to coordinate host sites and international preceptors between multiple US programs with G/I APPEs in a similar geographic region.

STUDENT CONSIDERATIONS

Just as extensive consideration goes into preparing US and international preceptors for educating students, so too must consideration be given to preparing US students for G/I APPE experiences. Student pharmacists interested in global education have opportunities to participate in medical missions, student exchange programs, and APPE practice experiences abroad. These students must be carefully selected. Schools should establish minimum requirements as well as definitive criteria for selecting students who will represent the institution internationally. Established organizations such as the International Pharmaceutical Sciences’ Federation and Christian Pharmacists Fellowship International have their own application and selection processes.21,22 These processes should ensure that students selected possess necessary professional abilities, exhibit cultural sensitivity and intercultural communication skills in general, an understanding of the culture to which they will be traveling, and an understanding that they will represent their institution and the profession of pharmacy. During the recruitment process, care must be taken to ensure students understand the experience is educational and not a vacation. Predeparture discussions should include transparency about the purpose of the experience with particular attention to addressing host country needs and student expectations.

Programs must be as explicit as possible in defining student expectations while they are participating in G/I APPEs. The program has the prerogative to accept only those student pharmacists who will represent the school well and possess the capabilities to perform well in cultures other than their own. Students applying for the G/I APPE should provide a personal statement in which they explain their reasons for seeking the international experience. Such statements should require students to establish objectives they wish to accomplish during the experience and how those objectives relate to program-specific outcomes. Students’ personal statements should demonstrate the presence of a genuine interest in understanding pharmacy in other countries and cross-cultural collaboration. These essays should show evidence of self-directed preparation for the experience. It is also important to evaluate the level of flexibility and adaptability of individual students to cultures different from their own.

Additional application criteria may include student characteristics such as prior international experience, fluency in an applicable language, academic standing, leadership, community involvement, ability to work as part of a team, career goals, cultural sensitivity, communication skills, problem solving ability, and maturity.23,24 None of these criteria are deemed essential and should be weighed differently based on the needs of the population served, preceptor, and experience.25 While time consuming to obtain and evaluate, interviews and letters of reference may also be beneficial in the selection process.26

In the selection of students for G/I APPE experiences, it is important to assure that they will be cognizant of and adhere to required laws, regulations, and emergency procedures.27 Only students who have a consistent positive record of professional conduct should be selected for G/I APPEs. Student selection criteria should be based on site-specific situations (eg, type, location, and nature of experiences).

When recruiting students, programs should be aware of potential barriers students face if selected, including concerns about experience affordability. These may be lessened by financial assistance through the university and/or pharmacy program, individual student fundraising, scholarships, or student loans. Other barriers such as significant health conditions requiring specialized care or medications are not as easily overcome and could be considered as exclusion criteria for the G/I APPE.

Learning Outcomes, Objectives, and Performance Activities

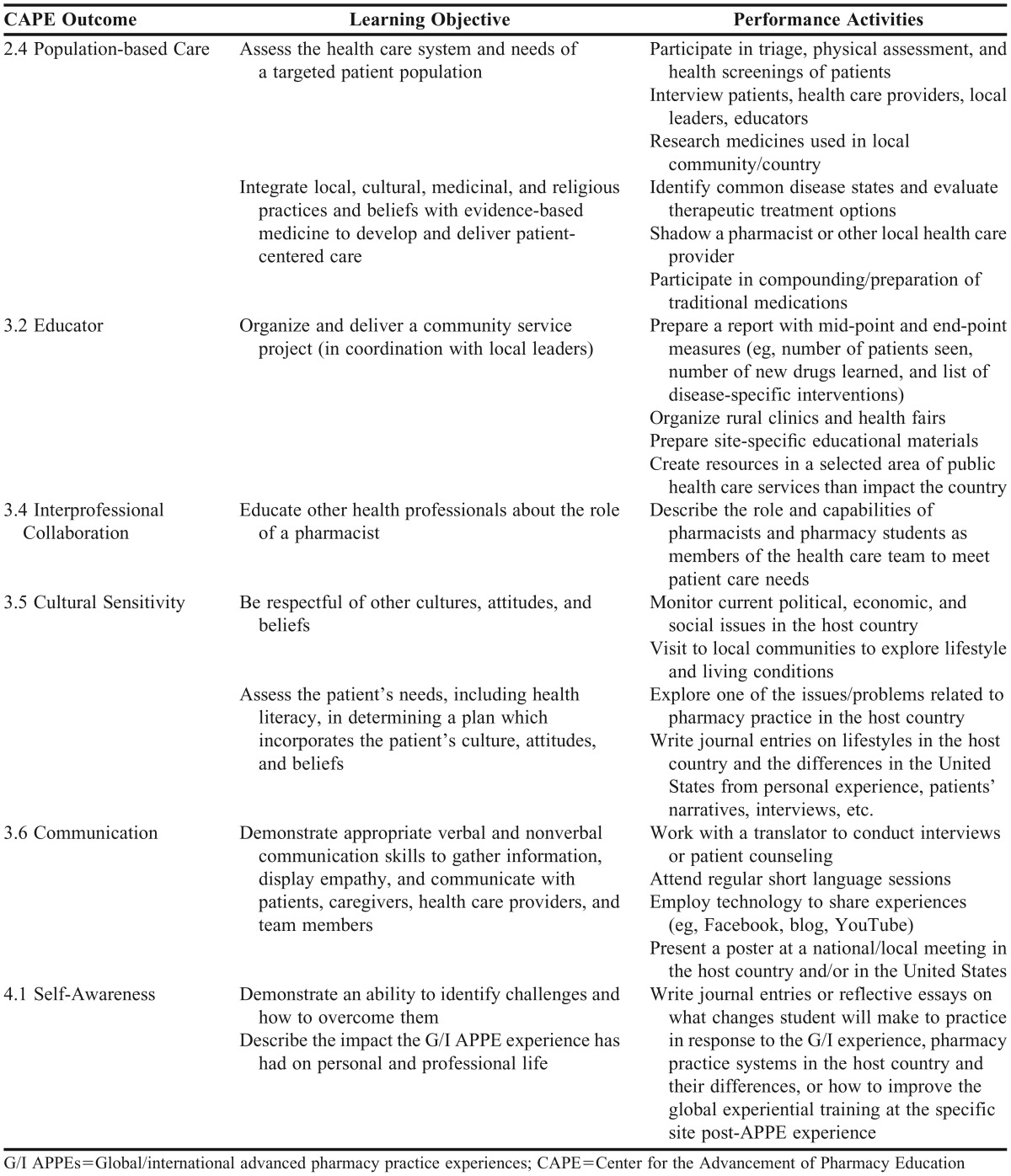

The establishment of essential learning outcomes, objectives, and performance activities for global training of health professions students assures that graduates have adequate core competencies for practice in diverse health care systems. Learning outcomes guide development of professional knowledge and skills and should be structured in association with an active-learning process that impacts the quantity and nature of educational outcomes.28,29 Well-defined and effectively managed learning outcomes are the foundation for the curriculum and provide a framework for programmatic evaluation.4 Professional and personal development of students is determined by learning outcomes.30 In experiential training, learning outcomes provide structure and direction for training.31 Broad learning outcomes may be similar across different pharmacy programs; however, specific learning objectives will need to be developed for each international experience. While learning outcomes and specific activities may vary by site, some core outcomes may be shared among sites. The recent 2013 update to the CAPE Outcomes represents a significant shift in student learning outcomes towards the affective domain within pharmacy curriculum. Development of the affective domain can be challenging and often requires varied experiences and self-reflection to demonstrate competency. In particular, the CAPE Outcomes identify “providing care for diverse populations, contributing to the health and wellness of individuals and communities […] and educating a broad range of constituents” as key functions of future pharmacists.17 Global/international APPEs are unique opportunities for students to develop competency in many of the CAPE Outcomes such as: Population-based Care, Educator, Inter-professional Collaboration, Cultural Sensitivity, Communication, and Self-Awareness.17 Incorporation of the CAPE Outcomes into a structured curriculum must allow for the introduction, reinforcement, and demonstration of key knowledge, skills, and attitudes essential for being successful as a student participant in global education and global health activities. Careful curriculum design with a focus on cultural sensitivity will enable students to progress to the higher level of thinking and relevant attitudes required for a global student engaged in experiential training. A more complete description of how G/I APPEs meet the CAPE 2013 outcomes has been completed by the GPE-SIG in a report to AACP.32

The learning outcomes should be developed by seeking input and consensus from students, faculty members, professionals, community groups, and host sites.31 Learning outcomes must be clear to students and instructors prior to the experience.28 Learning outcomes can be achieved by observation, doing, and experiencing. Therefore, outcomes should include reflective activities as a key learning method.33,34

Learning objectives are the means of accomplishing learning outcomes and should be directly tied to the established learning outcomes for each G/I APPE. Objectives and expectations should be explicitly outlined in the course syllabus and coordinated with the preceptor. Standards (eg, ACPE, CAPE) for quality of professional education play a role in development of learning objectives for global education. The ACPE curricular standard 12 addresses global pharmacy education and reinforces its value to education of student pharmacists. In the ACPE Standards 2016, Standard 10.15 emphasizes the importance of clearly defined expectations for practice experiences.2

Although important, neither cultural immersion nor learning objectives are a guarantee that transformative learning will occur. Asking students to perform at low levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy (ie, knowledge, comprehension) will not ensure that they are moving towards higher competency of the broad learning outcomes associated with these experiences. Describing disease states or recalling medications used in an international setting will not push students towards higher levels of engagement with the experience. Specific learning objectives for international experiences should be written at higher levels of the Bloom’s Taxonomy. Other health care groups have proposed standards or best practices for cultural training for various health care students studying abroad. The Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health Training (WEIGHT Guidelines) proposed best practices and a group specific to physical therapy performed a modified Delphi process to adapt them to physical therapy students.35,36

Learning does not occur independently of social or cultural environments but rather culture and systems affect learning objectives.29 Communication with members of other cultures occurs both verbally and nonverbally. Some placements will require language proficiency but in other cases, students may work with interpreters. Learning objectives should address the potential for bias, power imbalances, and neutrality during interpretation 37 Objectives for G/I APPEs that avoid comparisons and instead seek commonalities and prompt students to identify strengths in the community are an effective method of achieving transformative learning.38 Learning objectives should help students realize that they are learning from other cultures and health systems rather than attempting to implement their own health care system or practice model at the host site.

Performance activities are measurable activities that can be used to achieve learning objectives and demonstrate achievement of outcomes. Specific performance activities to meet G/I APPE learning objectives that reinforce knowledge, skills, and attitudes include: reflection,19,26,33,39 journaling,19,26 written reports,33,40,41 presentations,19,33 group discussions,19 and blogging.19 A portfolio may be an effective method to document achievement of learning outcomes for students on G/I APPEs. While not formally evaluated in the global health setting, debriefing sessions after returning from the host country are used as a teaching method for international experiences.42,43 Bender et al provide a valuable review of the literature on debriefing as a learning tool and propose a structured approach to debriefing sessions specifically for global health experiences.44

Resource needs and assets of the host country or site should be considered when designing activities for a G/I APPE. Requests by the sending institution for special activities or host country preceptors could impose a strain on host resources and may represent an ethical dilemma. Considering assets of the host site assures that local strengths are leveraged in the development of performance activities.10 With these considerations, student performance activities should seek to provide service for the host country when possible, while maximizing their strengths. Examples of learning objectives and performance activities for G/I APPEs, based on the CAPE Outcomes, are listed in Table 2. The AACP GPE-SIG Task Force identified four categories for performance activities for global APPE initiatives: patient care, health care systems, communication, and personal development and growth.

Table 2.

Suggested Outcomes, Objectives, and Performance Activities for G/I APPEs

Students on global experiential trainings are challenged with a wide range of patient care situations.19 Patient-centered care is based on therapeutic guidelines and relevant social, cultural and economic issues.26,31 Students may perform patient education, counseling, and develop patient accessible materials as a means of increasing patient participation and engagement.19,28,41 Students may be engaged with drug therapy evaluation including documenting patient history, laboratory results and physical examination, and evaluation of treatment options with adequate consideration of traditional or local complementary and alternative therapeutic agents. Performance activities in patient care may include review of the most common diseases and medicine or assessment of treatment outcomes in the host country.28 Students may benefit from reflecting on how their G/I patient care experiences will impact how they will practice in the United States.

In terms of health care systems, G/I APPEs provide opportunities for students to evaluate pharmacy operations and services at their global practice site.26 Students may identify strengths and weaknesses of the medication distribution systems including management of drug supply, dispensing procedures and medication records. Students may also develop an ability to analyze differences between health care systems.40,45 However, as previously described, outcomes drawing contrasts may hinder students from experiencing transformative learning.38 Therefore, students benefit from describing how culture impacts health and health care provided at the G/I APPE site. Students may be prompted to consider how understanding a different health care system could be used to improve the US health care system.

A principal outcome of the G/I APPE experience is developing the ability to interact with patients and exhibit improved proficiency in cultural sensitivity, including intercultural communication. International service-learning programs include communications and language skills as an objective.39 Students may practice culturally adequate communication skills not only during interactions with patients but also with other health care practitioners, faculty members, and students.26 They may practice these skills through delivering patient-specific counseling and oral presentations.26 Students may rely more on nonverbal communication while abroad than when in their own culture; thus, learning objectives may include recognition of appropriate and inappropriate nonverbal communications.

Study abroad experiences provide personal development opportunities and growth that allows students to increase awareness and appreciation of cultural differences and traditions.19,34,46 International programs include awareness of social justice and equal access to care as outcomes, as well as cultural awareness and sensitivity.30,38 Development of personal traits such as psychological hardiness is associated with successful experiences in study abroad programs. Individuals with this trait experience activities as interesting and enjoyable, as being a matter of personal choice, and as important stimuli for learning. They adopt coping strategies that are active and problem-focused. Students can improve psychological hardiness through redefining challenges as opportunities for growth rather than as threats to their personal security.47 Conflicts of interest between the host country and the sending institution may emerge and provide an opportunity for students to explore the ethical implications of their experiences.

Cultural Sensitivity and Preparedness

Exposure to a culture does not guarantee increased cultural competency, rather, it is a fertile ground upon which to build cultural sensitivity.48 It is important to send students abroad with some baseline level awareness about the host country’s culture. Students who are well prepared culturally for their experience are less likely to experience culture shock and homesickness or interpersonal conflicts. This type of preparation also prevents students from offending preceptors, coworkers, or patients in their host countries or even damaging carefully built relationships between the home and host institutions. As a result, there should be didactic content and activities planned throughout the curriculum and prior to the G/I APPE that allow students to develop cultural sensitivity.

The ideal cultural preparation for students combines cultural-general training (core competencies that individuals can develop that are not specific to any culture) with country-specific and site-specific training.49,50 It is important to guard against stereotyping. Determinants such as socioeconomic status, educational level, occupation, and family values and belief systems may outweigh ethnicity for an individual patient.50 Students should also be aware of intercultural communication differences. Educational hierarchy norms and gender roles in their host country may differ greatly from their local education. For example, while questioning instructors in a US-based program may be accepted and encouraged, it may not be as accepted in the host country.9,10 In addition to predeparture cultural assistance, students may have less culture shock while abroad if the home institution supports them by accentuating the positives of the host country/site, assisting students with problem solving, providing practical aids, monitoring closely for problems, and offering counseling if needed.51

Recommendations for Student Considerations

Schools of pharmacy should develop specific selection criteria for students including their level of cultural sensitivity, ability to represent the school, level of psychological hardiness, and/or other criteria specific to the site. Clear outcomes, objectives, and performance activities for G/I APPEs must be established and be explicitly understood by the preceptors and the students prior to the practice experience. A primary outcome of any G/I APPE experience should be the development of cultural sensitivity. When designing learning objectives and activities schools should consider the values of the host country and availability of cultural and educational opportunities in the host country while being sensitive to host resources. When assessing learning outcomes, programs should utilize an appropriate method of learning assessment for the affective domains. Lastly, schools should embed their curriculum with didactic content and activities, which promote global citizenship and cultural sensitivity.

Students on G/I APPEs should develop personal goals and objectives. While on the G/I APPE, students should demonstrate a commitment to contributing to pharmacy education, patient care, and cultural sensitivity. They should seek to improve their cultural literacy by investigating the culture, religious beliefs, language and all other pertinent aspects prior to the practice experience. All students must comply with all professional guidelines and regulations within the host country. Students should aim to address the needs of the host country through presentations, outreach, or community service. Lastly, students should ensure they have secured funding prior to the G/I APPE through grants, scholarships, or loans.

CONCLUSION

Expansion of pharmacy education to include a G/I APPE offers students and faculty members the opportunity to learn and practice cultural sensitivity, patient care, communication, and other skills. Care must be taken in selecting qualified, well-trained preceptors to guide student learning toward specific educational outcomes. These preceptors do not need to be US-based pharmacists, but their skills and abilities should ensure they would be able to facilitate achievement of learning outcomes associated with the G/I APPE.

Students should be selected to ensure they have the skills and attitudes needed to engage in culturally appropriate learning and adequately represent the school. Learning outcomes, objectives, and performance activities on the G/I APPE can vary widely but should be well defined prior to departure. For these experiences to be beneficial, cultural sensitivity training for both students and faculty members should be completed prior to the G/I APPE. This will ensure that the students have a good understanding of global citizenship and are culturally sensitive to meet the demands of a G/I APPE experience.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alsharif N DA, Abrons JP, et al. Current practices in global/international advanced pharmacy practice experiences: home/host country or site/institution considerations. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016;80(3) doi: 10.5688/ajpe80338. Article 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. 2015; https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2015.

- 3. Global Health Training in Graduate Medical Education: A Guidebook, 2nd Edition. 2 ed. San Francisco: Global Health Education Consortium; 2011.

- 4.Rassiwala J, Vaduganathan M, Kupershtok M, Castillo FM, Evert J. Global health educational engagement - a tale of two models. Acad. Med. 2013;88(11):1651–1657. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a6d0b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson C, Bates I, Brock T, et al. Highlights from the FIPEd global education report. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2014;78(1):4. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, Fawzi WW, Holmes KK, Gardner P. Global health in medical education: a call for more training and opportunities. Acad. Med. 2007;82(3):226–230. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305cf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Littlefield TC. Academic Pharmacy’s Role in Advancing Practice and Assuring Quality in Experiential Education: Report of the 2003-2004 Professional Affairs Committee. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2004;68(3):S8. [Google Scholar]

- 8. AACP. Academic Practice Partnership Initiative Preceptor-Specific Criteria of Excellence. Accessed October 11, 2014.

- 9.Arent R. Bridging the Cross-Cultural Gap: Listening and Speaking Tasks for Developing Fluency in English. Unversity of Michigan Press; ELT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiner SG, Totten VY, Jacquet GA, et al. Effective teaching and feedback skills for international emergency medicine “train the trainers” programs. J. Emerg. Med. 2013;45(5):718–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campinha-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services. Cleveland, OH: Transcultural C.A.R.E. Associates; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institutes of Health- Cultural Competency. http://www.nih.gov/institutes-nih/nih-office-director/office-communications-public-liaison/clear-communication/cultural-respect . Accessed March 24, 2016.

- 13.Evergreen SDH, Robertson KN. How do Evaluators Communicate Cultural Competence? Indications of Cultural Competence through An Examination of the American Evaluation Association’s Career Center. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation. 2010;6(14):58–67. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goerke V, Kickett M. Working towards the Assurance of Graduate Attributes for Indigenous Cultural Competency: The Case for Alignment between Policy, Professional Development and Curriculum Processes. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives. 2013;12(1):61–81. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Hlth Care Poor and Underserved. 1998;9(2):117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker MC, Mak AS. From Classroom to Boardroom and Ward: Developing Generic Intercultural Skills in Diverse Disciplines. J. Of Stud. In International Education. 2013;17(5):573–589. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 educational outcomes. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2013;77(8):162. doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li G. Promoting Teachers of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CLD) Students as Change Agents: A Cultural Approach to Professional Learning. Theory Into Practice. 2013;52(2):136–143. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittmann-Price RA, Anselmi KK, Espinal F. Creating opportunities for successful international student service-learning experiences. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2010;24(2):89–98. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0b013e3181d3994a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ono Y, Chikamori K, Shongwe ZF, Rogan JM. Reflections on a Mutual Journey of Discovery and Growth Based on a Japanese-South African Collaboration. Professional Development in Education. 2011;37(3):335–352. [Google Scholar]

- 21.IPSF Student Exchange Program. http://www.ipsf.org/student_exchange . Accessed 3/20/2015.

- 22.Christian Pharmacist Fellowship International- Outreach Activities. http://www.cpfi.org/outreach-activities

- 23.Bress AP, Filtz MR, Truong H-A, Nalder M, Vienet M, Boyle CJ. An advanced pharmacy practice experience in Melbourne, Australia: practical guidance for global experiences. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 2011;3(1):53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owen C, Breheny P, Ingram R, Pfeifle W, Cain J, Ryan M. Factors associated with pharmacy student interest in international study. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2013;77(3):54. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown DA, Ferrill MJ. Planning a pharmacy-led medical mission trip, part 3: development and implementation of an elective medical missions advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) rotation. Ann. Pharmacother. 2012;46(7-8):1111–1114. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werremeyer AB, Skoy ET. A medical mission to Guatemala as an advanced pharmacy practice experience. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2012;76(8):156. doi: 10.5688/ajpe768156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson JW, Merry SP, Franz WB. Rules of engagement: the principles of underserved global health volunteerism. Am. J. Med. 2012;125(6):612–617. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sefton AJ. New approaches to medical education: an international perspective. Med. Princ. Pract. 2004;13(5):239–248. doi: 10.1159/000079521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niemantsverdriet S, van der Vleuten CP, Majoor GD, Scherpbier AJ. An explorative study into learning on international traineeships: experiential learning processes dominate. Med. Educ. 2005;39(12):1236–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mu K, Coppard BM, Bracciano A, Doll J, Matthews A. Fostering cultural competency, clinical reasoning, and leadership through international outreach. Occup Ther Health Care. 2010;24(1):74–85. doi: 10.3109/07380570903329628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valani R, Sriharan A, Scolnik D. Integrating CanMEDS competencies into global health electives: an innovative elective program. CJEM. 2011;13(1):34–39. doi: 10.2310/8000.2011.100206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gleason SE. Connecting Global/Internationa Pharmacy Education to the CAPE 2013 Outcomes: A report from the Global Pharmacy Education Special Interest Group. 2016. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/cape/Documents/GPE_CAPE_Paper_November_2015.pdf . Accessed March 24, 2016.

- 33.Nishigori H, Otani T, Plint S, Uchino M, Ban N. I came, I saw, I reflected: a qualitative study into learning outcomes of international electives for Japanese and British medical students. Med. Teach. 2009;31(5):e196–201. doi: 10.1080/01421590802516764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niemantsverdriet S, Majoor GD, van der Vleuten CP, Scherpbier AJ. ‘I found myself to be a down to earth Dutch girl’: a qualitative study into learning outcomes from international traineeships. Med. Educ. 2004;38(7):749–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crump JA, Sugarman J. Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health T. Ethics and best practice guidelines for training experiences in global health. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010;83(6):1178–1182. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pechak CM, Black JD. Proposed guidelines for international clinical education in US-based physical therapist education programs: results of a focus group and Delphi Study. Phys. Ther. 2014;94(4):523–533. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fatahi N, Hellström M, Skott C, Mattsson B. General practitioners’ views on consultations with interpreters: a triad situation with complex issues. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care. 2008;26(1):40–45. doi: 10.1080/02813430701877633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foronda C, Belknap RA. Transformative learning through study abroad in low-income countries. Nurse Educ. 2012;37(4):157–161. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0b013e31825a879d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez-Mier EA, Soto-Rojas AE, Stelzner SM, Lorant DE, Riner ME, Yoder KM. An international, multidisciplinary, service-learning program: an option in the dental school curriculum. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2011;24(1):259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finkel ML, Fein O. Teaching medical students about different health care systems: an international exchange program. Acad. Med. 2006;81(4):388–390. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suarez-Balcazar Y, Hammel J, Mayo L, Inwald S, Sen S. Innovation in global collaborations: from student placement to mutually beneficial exchanges. Occup. Ther. Int. 2013;20(2):97–104. doi: 10.1002/oti.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dell EM, Varpio L, Petrosoniak A, Gajaria A, McMcarthy AE. The ethics and safety of medical student global health electives. Int J Med Educ. 2014;5:63–72. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5334.8051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curtin AJ, Martins DC, Schwartz-Barcott D, DiMaria L, Soler Ogando BM. Development and evaluation of an international service learning program for nursing students. Public Health Nurs. 2013;30(6):548–556. doi: 10.1111/phn.12040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bender A, Walker P. The obligation of debriefing in global health education. Med. Teach. 2013;35(3):e1027–1034. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.733449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Myhre K. Exchange students crossing language boundaries in clinical nursing practice. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2011;58(4):428–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carpenter LJ, Garcia AA. Assessing outcomes of a study abroad course for nursing students. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2012;33(2):85–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harrison JK, Brower HH. The Impact of Cultural Intelligence and Psychological Hardiness on Homesickness among Study Abroad Students. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad. 2011;21:41–62. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anderson PH, Lawton L. Intercultural Development: Study Abroad vs. On-Campus Study. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad. 2011;21:86–108. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Root E, Ngampornchai A. “I Came Back as a New Human Being”: Student Descriptions of Intercultural Competence Acquired Through Education Abroad Experiences. J. Of Stud. In International Education. 2013;17(5):513–532. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Misra-Hebert AD. Physician cultural competence: cross-cultural communication improves care. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2003;70(4):289. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.70.4.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carey CE. International HPT: Rx for Culture Shock. Performance Improvement. 1999;38(5):49–54. [Google Scholar]