Abstract

Domain 3 of the Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) 2013 Educational Outcomes recommends that pharmacy school curricula prepare students to be better problem solvers, but are silent on the type of problems they should be prepared to solve. We identified five basic approaches to problem solving in the curriculum at a pharmacy school: clinical, ethical, managerial, economic, and legal. These approaches were compared to determine a generic process that could be applied to all pharmacy decisions. Although there were similarities in the approaches, generic problem solving processes may not work for all problems. Successful problem solving requires identification of the problems faced and application of the right approach to the situation. We also advocate that the CAPE Outcomes make explicit the importance of different approaches to problem solving. Future pharmacists will need multiple approaches to problem solving to adapt to the complexity of health care.

Keywords: decision-making, problem-solving, CAPE outcomes, pharmacy education

INTRODUCTION

The Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) 2013 Educational Outcomes is an initiative intended to serve as a guide and foundational framework for curriculum design by colleges and schools of pharmacy across the United States.1 Developed by the CAPE 2013 panel, in association with the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP), the educational outcomes are intended to represent the target academic and professional skills that pharmacy school graduates should learn throughout their professional education and measurably achieve upon graduation. To best model a well-rounded professional experience, the CAPE 2013 Outcomes were constructed in four basic domains: foundational knowledge, essentials for practice and care, approach to practice and care, and personal and professional development.1 These broad domains highlight the AACP intent that all doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) graduates practice at the highest professional level, integrating fundamental knowledge and skills with leadership, professional practice, and patient care.

Within the four domains of the CAPE Outcomes are associated subdomains and suggested learning objectives designed to guide curriculum planning and provide a measure of educational assessment. Many of these learning objectives emphasize the importance of problem-solving and decision-making competencies in graduates of pharmacy schools, but they are not explicit about what is meant by problem solving or decision making.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines a decision as “a choice that you make about something after thinking about it: the result of deciding.”2 A problem is defined as “something that is difficult to deal with: something that is a source of trouble, worry, etc.”3 Therefore, decision making and problem solving are processes around which difficult choices are made. For the purposes of this paper, they will be considered synonymous.

An important step in the decision-making process is framing.4 Good decision makers create decision frames designed for specific problems.5 Decision frames delineate how a question is set up to be answered. Framing considers issues such as the perspective taken, elements of the problem to be considered, and criteria used to choose one solution over another. Framing helps simplify the problem by including some and excluding other information. When choosing a restaurant for an anniversary dinner with a spouse, a person simplifies the options by listing a limited number of key characteristics desired in a restaurant (eg, ambiance, menu, price) while ignoring others (eg, speed of service, nearby location). A different perspective or situation might stress different choice characteristics.

Perspective is crucial to framing decisions because it constrains problems and guides their process and direction. For example, a clinical perspective typically emphasizes therapeutic outcomes and adverse events associated with care, while an economic perspective highlights resources associated with those outcomes and events. Therefore, clinicians might place greater stress on an adverse event like mild nausea and vomiting than an economist if the event adds little additional economic cost to treatment.

Decision-making in the CAPE Outcomes seems to emphasize a clinical perspective. Domain 1, foundational knowledge, is explicit that students need to know about therapeutic problem solving. Other mentions of problem solving occur in Domain 3, approach to practice and care and Domain 4, personal and professional development, but the mentions are ambiguous about the perspective or desired framing of the problems.

An argument can be made that other perspectives and frames are needed in decision making within the profession. Increasingly, pharmacists need to consider perspectives of diverse groups of stakeholders in decision-making processes, which becomes more important when dealing with complex, ambiguous problems that require imagination and flexibility.

The current curricula in pharmacy schools and colleges prepare students to solve therapeutic problems, but not all problems in practice are completely clinical. If a clinical approach to nonclinical problems is used, practitioners can fall into decision traps. Decision traps bias problem solving by funneling processes in directions that might lead to less than optimal outcomes.5 For example, good clinical decision-making processes can lead to outcomes that might be morally questionable or economically unsustainable. Thus, it is critically important that educators can clearly discuss various problem-solving approaches with students and that graduates can incorporate these approaches to successfully apply clinical knowledge and professional judgment to patient care. This paper intends to provide guidance to pharmacy educators on methods to address problem-solving competencies by further defining the steps involved with five basic approaches to decision making as suggested in the literature.

LITERATURE SEARCH

A literature search was conducted to identify explicit problem-solving approaches used in pharmacy education. The goal was to identify common elements that might offer a generic problem-solving framework that could be applied across the curricula. The search was started by identifying how decision-making was incorporated into the curriculum at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) School of Pharmacy to detect different approaches used in the curriculum and the steps involved. The search revealed that the curriculum explicitly used clinical, managerial, ethical, economic, and legal problem-solving approaches in educating pharmacy students. Course material was reviewed for specific content regarding each of the approaches to gather (1) basic definitions used, (2) steps involved in the decision-making process, (3) how problems were framed, and (4) intended outcomes of decisions. Citations supporting those processes were also collected.

The search of the curriculum was supplemented by a comprehensive literature review of the PubMed database completed in October 2014. This review sought to identify additional citations regarding decision-making in pharmacy education. The search terms used alone or in combination were “problem-solving,” “decision-making,” and “pharmacy education.” Inclusion criteria consisted of any article discussing steps or processes for solving specific types of problems (eg, ethical, economic). Excluded articles described philosophies of problem solving like reflective practice or discussions of general processes like critical thinking or application of the scientific process.

FINDINGS

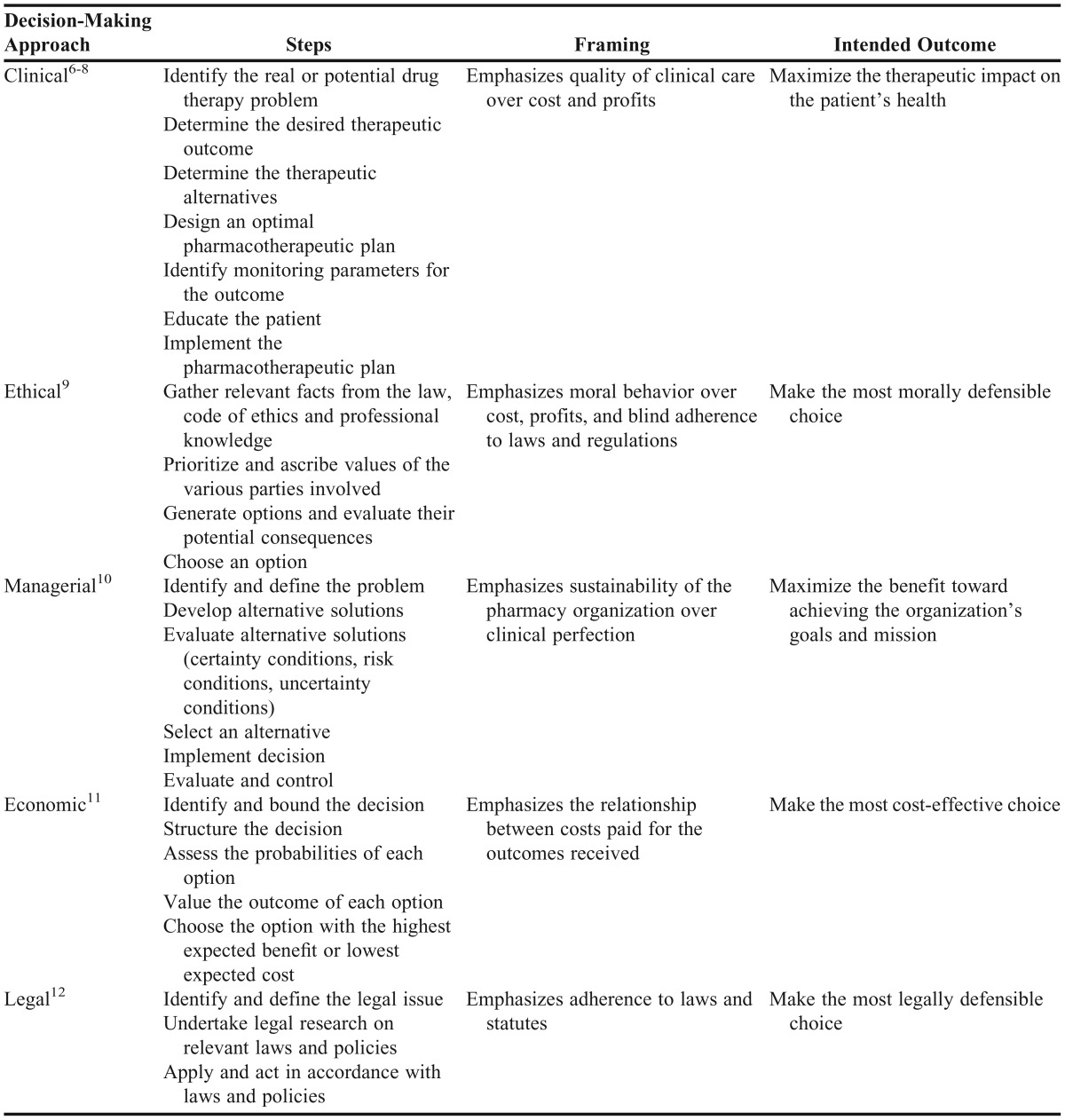

The five specific approaches to decision-making currently being taught at VCU School of Pharmacy are summarized in Table 1. The PubMed literature review did not reveal any additional specific decision-making frameworks. Decision-making in pharmacy education literature centered primarily on a clinical problem-solving framework for topics related to disease management, nonprescription medicine use, and a range of other clinical problems.

Table 1.

Five Decision-making Approaches Identified in the Pharmacy Literature

The steps of the five approaches and the intended outcomes as described in the literature are summarized in Table 1. Each approach used a similar general process consisting of identifying and defining the problem, suggesting and weighing solutions, making a choice, and assessing the results of the choice. However, the general process of the approaches differed in two major ways: first, how the problem is framed and second, the intended outcome of the decision.

The following scenario of a problem faced by a community pharmacist demonstrates how the decision process and outcome might differ depending on the approach chosen: On Monday, in the middle of the busy holiday season, the pharmacist-in-charge of a national chain receives a call from one of the store’s technicians that the latter is sick and cannot make her shift. This absence will leave the pharmacist with only one technician for the remainder of the day to complete the normal workflow. The manager of the busy store informs the pharmacist that, being shorthanded, they may need to cut corners to get all of the work done. The pharmacist notices that a line is beginning to form at the pharmacy counter and a decision must be made on how to best approach the day’s tasks with the staff available.

The main focus of a clinical decision-making approach is patients and their overall well-being.6-8 In the scenario above, the problem can be framed as being shorthanded a pharmacy technician, which is a threat to the patient receiving the highest level of care possible. This hinders the pharmacist’s ability to provide quality care. In the clinical framework, cost of care and pharmacy profitability take a back seat to patient care. Only the best care possible is acceptable; therefore, the solution might be to call in another technician or pharmacist to work overtime at any cost. Closing the pharmacy early is another option if staffing is insufficient to provide care that is up to the minimal standards of the clinician. The pharmacist’s final decision should strive to maximize the therapeutic impact on patients’ health.

In an ethical decision-making approach, the main focus is achieving a morally defensible solution to the problem.9 With the example, the issue would be perceived as how having one less technician would affect the quality of patient care the pharmacist could provide, and whether it would be morally defensible to cut corners in the provision of care. If the pharmacist decided that the reduced level of care with only one technician was acceptable, the staff could proceed as normally as possible with their shifts. If, however, the level of care was deemed to be unacceptable in terms of safety, the pharmacist could decide to close the pharmacy until sufficient staff could be assembled. Because of the ambiguous nature of morality, individual perspectives may vary, but the goal is to derive a defensible solution that the general population would recognize as ethical and that the manager would find acceptable.

Managerial decision-making centers on the company itself and its ability to use the resources available to produce maximum efficiency.10 In this scenario, the problem would be perceived as how being short-staffed would affect the work flow of the pharmacy and how all daily tasks could be completed to the company’s goals and standards. Using a managerial approach to maximize the workflow, despite having one less technician, the pharmacist may decide to prioritize the filling of specific prescriptions based on time demands. Alternatively, to capitalize on efficiency, the pharmacist may decide to focus all resources on filling prescriptions and give low priority to immunization and counseling activities that may require more time and attention from the staff. With either solution, the pharmacist’s focus would be maximizing the organization’s benefit from the daily activities performed.

Using an economic decision-making approach, the goal is to maximize cost-effectiveness with a solution that is most profitable or least costly, depending on the situation.11 In the example, the problem might be viewed as how having one less technician would affect the daily profit margin of the pharmacy. In order to maximize the cost-effectiveness, an example solution would be to complete the normal workflow with the staff present, focusing efforts on activities with the greatest potential income, and without using resources to pay for an overtime technician. With this solution, the pharmacist makes the best use of the staff available to increase daily profits and minimize costs to the company.

The legal approach to decision-making is straightforward and simply involves taking actions that are deemed to be acceptable under the law.12 For the example scenario, a legal approach would view the issue as how being short-staffed would affect the ability of the pharmacist to perform his other duties within the scope of the law. The pharmacist would have to consult federal and state laws to consider the consequences if a staff member or patient is harmed as a result of understaffing and to ensure that activities legally entrusted to a pharmacist are not performed by a technician because of time constraints. Some interpretation of the law might be needed, but the pharmacist’s final decision would strive to be the most legally defensible choice.

Although these five decision-making approaches are presented as distinct entities, in practice, these methods are often combined to determine a final decision. Using these approaches in combination, however, may be difficult as solutions precipitated by one approach may be contradictory to another or may be simply bad business. A general example of this scenario, in the case of an inpatient setting, would be if a physician wants to use a medication for a patient, but when the request is submitted to the pharmacy and therapeutics committee, it is deemed too costly and thus not available for use.

In this scenario, the members of the committee used an economic and managerial approach to maximize the cost-effectiveness of medication procurement and use, while optimizing resource allocation and efficiency. This solution, however, may be arguably immoral in that patients may not receive the best medication for their particular condition. In contrast, if all physicians had the authority to prescribe and dispense their medication of choice for each patient, this approach may be moral, but would be of detrimental cost to the organization and a poor business decision. These contrasts reinforce the need to have an understanding of the different decision approaches, their use in practice, and the importance of professional discretion.

DECISION-MAKING IN THE PHARMACY CURRICULUM

The CAPE 2013 Educational Outcomes emphasize the importance of problem solving and decision making within a well-rounded pharmaceutical education. Integrating course material on decision-making approaches into the PharmD curriculum will help prepare future pharmacists to effectively manage different situations. The students should be able to apply the appropriate decision-making framework and problem solve when faced with situations that arise in pharmacy practice. Knowing which framework or frameworks to use will help graduates confidently manage issues in practice while using their clinical knowledge and professional experience to impact patient care.

A few studies explored potential practice-based rubrics used to assess students’ decision-making and problem-solving skills within the medical education field. These rubrics could potentially be used to assess pharmacy students’ understanding and appropriate application of decision-making approaches integrated into course material. Within nursing education, two distinct tools, the Assessment of Clinical Decision-making Rubric13 and the Ethical Decision-making Assessment Rubric,14 have strong empiric support for assessment of nursing students’ ability to make clinical and ethical decisions though neither has been adequately validated. The Assessment of Clinical Decision-making Rubric was designed to evaluate electronic journal entries submitted by nursing students describing their clinical decision-making process during a 3-week clinical practice experience. The rubric evaluated seven key components of clinical decision making, from defining the problem to reflecting on learning outcomes, similar to the clinical decision-making process described in this paper.

The Ethical Decision-making Assessment Rubric was designed to assess nursing students’ ethical decision-making process during a 36-question, open-ended exercise using three ethical conflict scenarios. The rubric evaluated five components of the ethical decision-making process, from perception of ethical conflicts to evaluating the ethical decision. Given the similarities of the decision-making steps evaluated in these two rubrics to the steps described in this paper, using such rubrics as tools for evaluation of the five decision-making approaches would be possible in pharmacy, but would need to be validated.

Within pharmacy education, Adamcik et al described a computer assessment program developed to assess fourth-year pharmacy students’ problem-solving skills through a set of four simulations targeting different aspects involved in critical thinking.15 These simulations, however, had poor correlations with other instruments of cognitive ability and thus require further evaluation.16 The best potential assessment tools within pharmacy education are the rubrics evaluated by Gleason et al,16 which provided a validated assessment of pharmacy students’ critical-thinking and problem-solving abilities across a 6-year PharmD program. Faculty evaluators used the Critical-thinking Rubric and the Problem-solving Rubric to assess student work samples for competency; these rubrics were based on VALUE (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education) Rubrics published by the Association of American Colleges and Universities.17

The Critical-thinking Rubric evaluated five components of the decision-making process: explanation of issues, evidence, influence of context and assumptions, student’s position, and conclusion/related outcomes. The Problem-solving Rubric evaluated six general problem solving steps, from defining the problem(s) to evaluation of outcomes. Both rubrics provide a basic framework for assessing pharmacy students’ critical-thinking and problem-solving abilities and could be further tailored to evaluate the specific steps involved in the five decision-making approaches outlined in this paper, following their integration within the PharmD curriculum.

DISCUSSION

In daily professional practice, pharmacists are faced with numerous critical choices that could potentially affect them, their patients, and their staff. When faced with such choices, a pharmacist must be able to use an appropriate decision-making process to ensure that a well thought out solution is attained.1 As shown through the example scenario, decision-making and problem-solving skills are an essential job responsibility for pharmacists. It is critical that all pharmacy students are taught how to successfully approach and frame a problem in practice to ensure quality patient care and the standing of our profession. This article reviewed five common decision-making approaches but there are others, such as the scientific method, which may be appropriate for specific situations.

One might question whether there is a need to specify a focus. Good problem solving should take into account more than one perspective. The CAPE Outcomes highlight clinical decision making in Domain 1.1 (learner), team-based decision-making in Domain 3.4 (collaborator), and creative decision-making in Domain 4.3 (innovator).1 Domains 3 and 4 may require more than one type of decision-making process that can help highlight the importance of nonclinical endpoints and population-based results instead of only individual clinical outcomes.

There is a well-known quote that states, “If your only tool is a hammer then every problem looks like a nail.” Restating the quote, it can be argued that, “If all pharmacy graduate students are taught primarily to use a clinical decision-making process, then every problem in pharmacy practice will look like a clinical one,” which is why it is important to understand the different approaches to decision-making and including the different decision-making processes in the CAPE Outcomes.

This paper identified clinical, ethical, managerial, economic and legal approaches to decision-making important for problem solving in pharmacy practice. This list is not definitive and leaves out many other general approaches (eg, the scientific method, reflective practice) and disciplines (eg, sociology, epidemiology). Indeed, almost every academic discipline has its own approach to framing problems, and the intended outcome of each approach may diverge depending on the specific problem.

There are limitations of this research. The paper is based on a problem identified within a single institution, and it is possible that other schools of pharmacy may be working on alternative methods for addressing this issue if a similar problem has been observed. Another limitation is that the topic of problem-solving is broad and the search terms used in the literature review may have overlooked important references.

CONCLUSION

The CAPE Outcomes recognize different domains in which decision-making takes place. Highlighting various approaches to decision-making other than clinical, like economic, legal, ethical, managerial and more could help students understand how to solve problems from all angles. Students will need to identify the best decision-making approach for the circumstances. Integrating all decision-making approaches in the PharmD curriculum is a way for students to think more critically when managing problems that arise. Greater attention to this issue is needed to guide curriculum design in schools of pharmacy across the United States.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial Disclosure Statement: There is no financial support to disclose.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement: There is no conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education. 2013 Educational Outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8) doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. Article 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. “Decision.” Def. 1. Merriam-Webster Online: Dictionary and Thesaurus. Merriam-Webster, Inc., 2014. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/decision Web. Accessed April 7, 2016.

- 3. “Problem.” Def. 1. Merriam-Webster Online: Dictionary and Thesaurus. Merriam-Webster, Inc., 2014. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/problem Web. Accessed April 7, 2016.

- 4.Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211(4481):453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russo JE, Schoemaker PJH. Decision Traps: The Ten Barriers to Brilliant Decision-Making and How to Overcome Them. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwinghammer TL. Chapter 1. Introduction: How to Use This Casebook. In: Schwinghammer TL, Koehler JM, editors. Pharmacotherapy Casebook: A Patient-Focused Approach. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant PJ, Pace HA. The Pharmacist’s Guide to Evidence-Based Medicine for Clinical Decision-Making. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krinsky DL, Berardi RR, Ferreri SP. Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs: An Interactive Approach to Self-Care. 17th ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2012. How to use the case problem-solving model. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wingfield J, Badcott D. “The Professional Decision-Making Process.” Pharmacy Ethics and Decision Making. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2007.

- 10.Donnelly JH, Gibson JL, Ivancevich JM. Fundamentals of Management. 9th ed. Chicago: Irwin; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll NV. Financial Management for Pharmacists: A Decision-Making Approach. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. Decision Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horrigan B. Materials on Problem-Solving Techniques. University of Canberra Law School. http://lgdata.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/docs/650/507713/Materials_On_Problem-Solving_Techniques.pdf. Accessed April 7, 2016.

- 13.Edelen BG, Bell AA. The role of analogy-guided learning experiences in enhancing students’ clinical decision-making skills. J Nurs Educ. 2011;50(8):453–460. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20110517-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Indhraratana A, Kaemkate W. Developing and validating a tool to assess ethical decision-making ability of nursing students, using rubrics. J Res Int Edu. 2012;8(4):393–398. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adamcik B, Hurley S, Erramouspe J. Assessment of pharmacy students’ critical-thinking and problem-solving abilities. Am J Pharm Educ. 1996;60(Fall):256–265. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gleason BL, Gaebelein CJ, Grice GR, et al. Assessment of students’ critical-thinking and problem-solving abilities across a 6-year doctor of pharmacy program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8) doi: 10.5688/ajpe778166. Article 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Association of American Colleges and Universities. VALUE Rubrics. http://www.aacu.org/value-rubrics. Accessed April 7, 2016.