Abstract

Background:

Workplace violence is a serious and problematic phenomenon in health care settings. Research shows that health care workers are at the highest risk of such violence. The aim of this study was to address the frequency of physical violence against Iranian health personnel, their response to such violence, as well as the contributing factors to physical violence.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted in 2011, in which 6500 out of 57,000 health personnel working in some teaching hospitals were selected using multi-stage random sampling. Data were collected using the questionnaire of “Workplace Violence in the Health Sector” developed by the International Labor Organization, the International Council of Nurses, the World Health Organization, and the Public Services International.

Results:

The findings revealed that 23.5% of the participants were exposed to physical violence in the 12 months prior to the study. Nurses were the main victims of physical violence (78%) and patients' families were the main perpetrators of violence (56%). The most common reaction of victims to physical violence was asking the aggressor to stop violence (45%). Lack of people's knowledge of employees' tasks was the most common contributing factor to physical violence (49.2%).

Conclusions:

Based on the results, legislating appropriate laws in order to prevent and control violence in the workplace is necessary. Moreover, developing educational programs to manage the incidence of physical violence should be on health centers' agenda.

Keywords: Health care worker, health personnel, Iran, physical violence, workplace violence

INTRODUCTION

Workplace violence (WPV) is referred to any incident or situation in which a person in his workplace or work-related circumstances is subjected to mistreatment, threats, or aggression.[1] WPV is one of the most important and complex issues in health care settings.[2,3] Health care workers are 16 times more likely to experience WPV than other workers. According to the International Council of Nurses, the likelihood of health care workers' exposure to violence is even higher than prison guards or police officers.[4] WPV is categorized into physical and non-physical (psychological) violence. Although all types of violence are destructive, physical violence can hurt victims physically and psychologically more than other forms.[5] Physical violence involves use of physical force against an individual or a group, and can lead to physical, psychological, or sexual harm and includes punching, kicking, slapping, shouting, pushing, biting, pinching, and wounding using sharp objects.[6]

In 2007, nearly 15% of work facilities were assigned to violent and threatening acts in USA.[7] Results of a study conducted during 2009–2010 in Italy showed that 13.4% of nurses reported at least one physical attack during the past year.[8] In Taiwan, 19.6% reported physical violence.[9] In Iran, the results of a systematic review study indicated that the prevalence of physical violence was between 9.1 and 71.6% and the most common types of physical violence were pushing or pitching, as experienced by 43% of participants.[10] Rahmani et al. pointed out that the prevalence of physical violence against emergency medical workers in East Azerbaijan was 37.7%.[11]

The outcomes of WPV include physical consequences such as increasing low back pain, symptoms of somatic and musculoskeletal disorders,[12] and psychological consequences such as posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, fear, depression, substance abuse, and poor quality of patient care.[13] Furthermore, health care workers suffer from job dissatisfaction,[14] poor quality of life,[15] and low self-esteem.[16] Although several studies have been carried out regarding WPV in Iran,[17,18,19] there is no overall feature about physical violence against health care workers. The aim of this study was to investigate the frequency of workplace physical violence among Iranian health care providers working in some teaching hospitals, their response to such violence, as well as the contributing factors to physical violence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2011 in some teaching hospitals across Iran. Study population comprised all health care workers including physicians, nurses, midwives, nurse aids, and paramedical personnel that numbered 57,000 according to the latest Ministry of Health and Medical Education statistics in 2011. Inclusion criteria included: (i) Working in a teaching hospital and (ii) having at least 1 year of experience. Exclusion criterion was participant's decision to discontinue from the study.

The participants were selected by multistage random sampling in three phases. In the first phase, all the provinces were included in this study (four provinces excluded due to administrative issues). Sample size of each province was calculated according to the proportion of health care professionals. In the second phase, hospitals were selected by cluster random sampling based on geographic areas. Thus, 135 teaching hospitals were selected. In the third phase, samples were selected by random sampling based on samples' size in each hospital. Sample size was estimated by the following formula and with a confidence interval of 1.96, power of 0.80, and d = 0.01:

m = (Z1 − α/2/d)2(P)(1 − p) m = (1.96/0.01)2(0.75)(0.25) = 7203

n = (M)(total)/M + total n = (7203)(65,000)/7203 + 65,000 = 6485

Data were collected using the international questionnaire of “Workplace Violence in the Health Sector” developed by the International Labor Organization (ILO), the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Nurse Council (ICN), and the Public Services International (PSI). The questionnaire contains five sections: (a) 21 items about personal and workplace data; (b) 17 items about physical violence; (c) 37 items about psychological violence (emotional abuse), which involves verbal violence, bullying/mobbing, and sexual harassments; (d) 8 items about the health sector; and (e) 3 open-ended questions on participants' views on WPV.[20] The questionnaire was translated from English to Persian by a bilingual person and then back-translated from Persian to English by another person who was also proficient in both languages. Then, after matching with the other existing Persian version,[21] the content validity of the questionnaire items was assessed by a committee including 11 experts who were interested in the research topic. Finally, the items were modified according to the experts' opinions. Moreover, the reliability of the questionnaire was confirmed by test-retest (r = 0.71) through completion by 180 health care workers employed in one of the teaching hospitals of Tehran. In this paper, only relevant findings to workplace physical violence are presented because of the extensive amount of data involved. Data were analyzed by descriptive statistics using SPSS software version 13.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Ethics Committee Approval Number: 14/86). Moreover, all of the participants were informed regarding the study aim. Informed consent was obtained from the health workers who agreed to participate in this study.

RESULTS

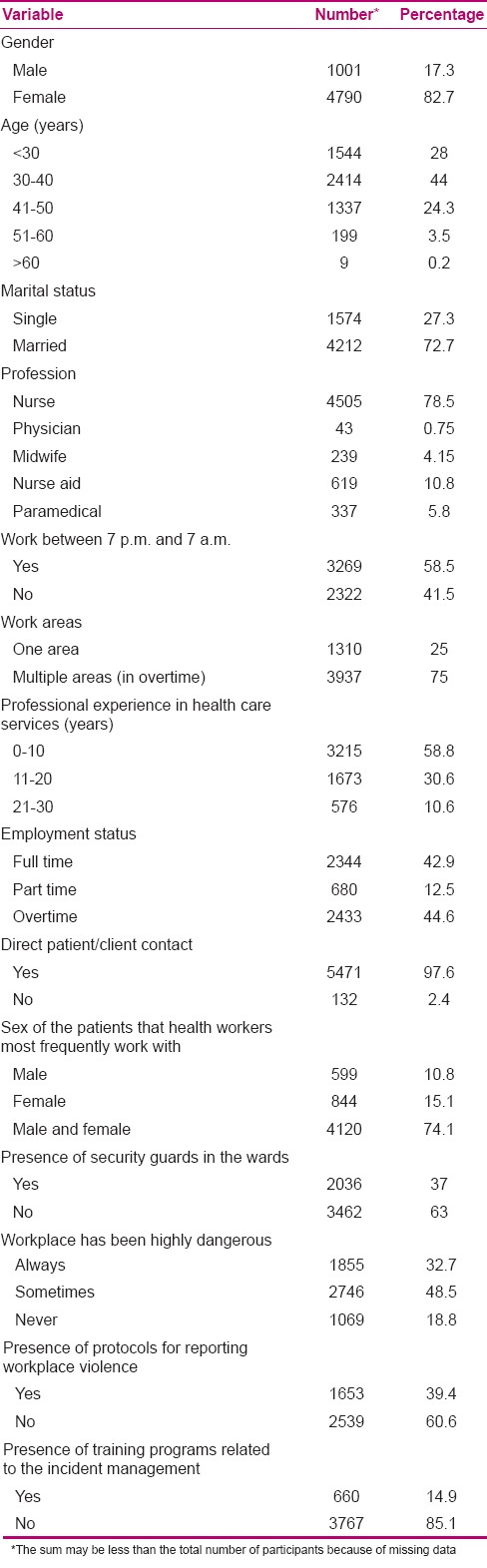

The survey response rate was 90.36%. The mean age of the participants was 34 ± 8.5 years, and 78.5% of the participants were nurses. The mean work experience was 10.35 ± 7.4 years. The majority of participants (85.1%) indicated that they had not received training program for dealing with workplace physical violence. Other demographic and work characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and work characteristics of the participants (N=5874)

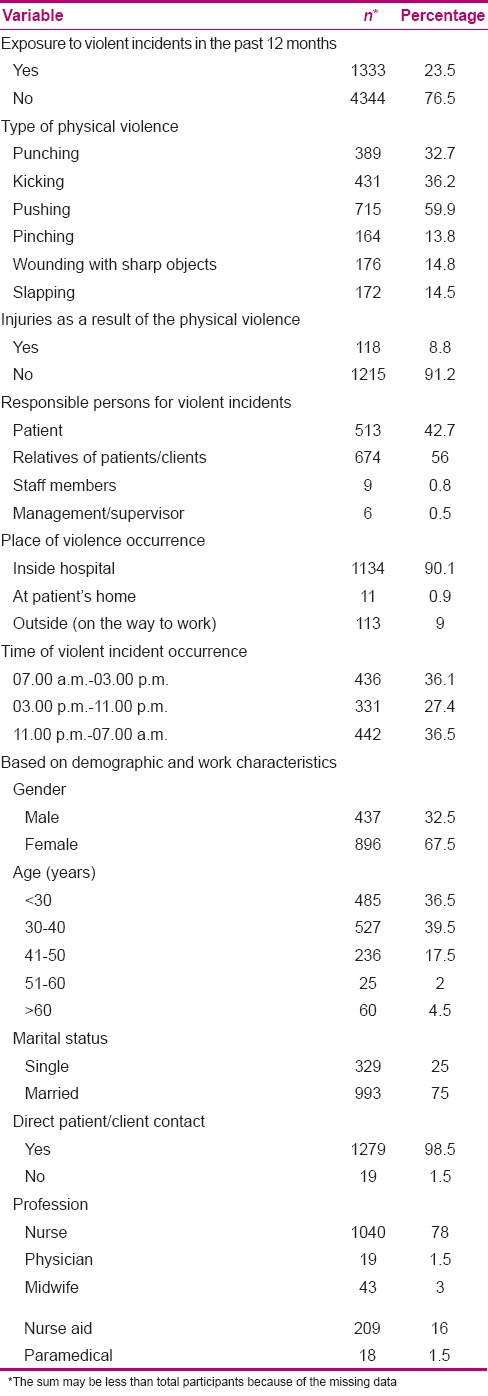

About 23.5% of the participants reported that they had been physically abused in the past year, and all of them happened without use of any weapons. Pushing (59.9%), kicking (36.2%), and punching (32.7%) were reported as the most frequent forms of workplace physical violence. Among the victims, 118 participants received serious injuries (8.8%). Moreover, 36.5% of physical violence occurred on the night shift. The majority of the physical incidents occurred inside the hospitals (90.1%), against female health workers (67.5%), and between the ages of 30 and 40 years (39.5%). Nurses were the main victim of physical violence (78%). Patients' families were the main perpetrators of physical violence (56%). Characteristics of physical violence and its forms are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequency of physical violence (N=1333)

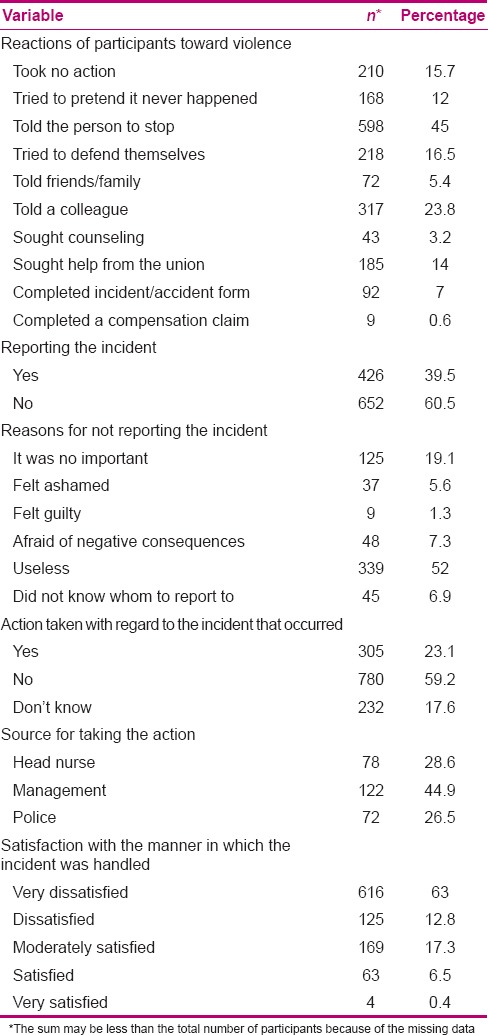

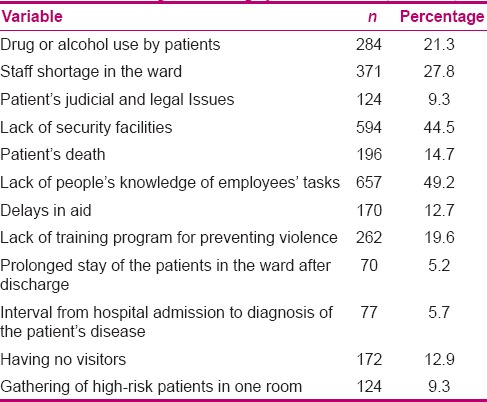

The most common reaction of victims to physical violence was asking the aggressor to stop violence (45%). Six hundred and fifty-two participants (60.5%) did not report violence and the most common reason for not reporting physical violence was they considered reporting it useless (52%) [Table 3]. Lack of people's knowledge of employees' tasks (49.2%) was the most common contributing factor to physical violence [Table 4].

Table 3.

Reactions of health personnel to physical violence (N=1333)

Table 4.

Contributing factors to physical violence (N=1333)

DISCUSSION

This study was performed in different cities of Iran in order to determine the frequency of physical WPV toward health professionals. The results showed that the health workers' exposure to physical violence was 23.5%. The result of a study in Jordan showed that 22.5% of hospital nurses were exposed to physical WPV.[22] Hasani et al.[23] reported that 15.93% of emergency staff were exposed to physical violence during the past 3 months. The incidence of physical violence in another study was 21%,[24] which is similar to the frequency obtained in the present study. But in some other studies,[12,25] between 46 and 70% of participants were exposed to physical violence, which exceeds the results of the present study. This may be due to cultural differences between countries or underreporting.

In the present study, pushing was the most frequent form of violence. Rahmani et al. indicated that the frequency of pushing and punching was 71.4% and 20.4%, respectively.[11] Erkol et al. noted that hitting, kicking, and scratching were the most frequent types of physical violence.[26] Talas et al. pointed out that hitting, pushing, or shoving was reported by 73.9% of victims,[27] which is consistent with the result of the present study.

The main source of violence was patient's family, which is consistent with the findings of other studies.[27,28] However, Merecz et al. showed that above 64% of psychiatric nurses and more than 16% of other nurses had frequently been subjected to patients' physical violence.[29] In another study, patients were the main cause of physical violence and threats to attack.[14] The difference could be attributed to cultural differences, and the constant presence of patient's family during hospitalization and coming into contact with medical staff and nurses in Iran.

The results showed that female health workers, especially between 30 and 40 years of age, were exposed to physical violence more than other workers, which is consistent with many reviewed studies.[9,30,31] In all these studies, WPV against female workers, who were often younger, was more than that of others. So, managers and health personnel, especially nurses, should identify these risk factors in order to prevent and manage such violence. Moreover, in the current study, nurses were the main victims of physical violence. Pich et al.[32] reported that nurses are at the highest risk of patient-related violence. This is thought to be due to their close contact with patients and/or their families.

The present study results also reveal that more than half of the participants did not report exposure to violence, and considered reporting useless. Furthermore, more than 60% of participants stated that there was no guideline for reporting violence in their workplace, and more than half of them said that no action has yet been taken to pursue the incidence of violence. AbuAlRub et al. reported that there was no procedure for reporting WPV in Iraq. Moreover, the most participants indicated that no specific policy had been thought up for dealing with violence.[33] This is congruent with the findings of another study which showed that only 23.6% of participants reported the physical violence.[24]

The most important reasons for not reporting included considering reporting useless and fear of being stigmatized as a troublesome and incompetent person. In other studies, almost all of the participants stated that no guidelines existed in their workplace for preventing and control of violence.[34,35] These findings indicate lack of proper staff training programs for preventing and managing violence, and also, lack of appropriate legislation and policy for pursuing received reports and managing violence in health care settings. However, results of a study in Australia showed that nearly 70% of health workers were satisfied with WPV control policies and reporting mechanisms,[36] which is inconsistent with the finding of the present study. It may be due to existence of transparent policies, appropriate legislation, and reporting mechanisms in developed countries.

In the present study, more than half of the participants believed that “lack of people's knowledge about staff tasks” was among factors associated with violence, which is in agreement with the results obtained by Rahmani et al.[11] So, lack of awareness can cause the patients and/or their relatives to have unrealistic expectations of health professionals and, consequently, unmet expectations lead to violence.

There are some limitations to the present study. First, the data were collected retrospectively, which might lead to recall bias. Second, due to the large sample size and self-reported method for data collection, missing data for each item was relatively significant. Finally, regarding the cultural sensitivities or the related stigma of violence victims, it is probable that participants might not have expressed all their experiences.

CONCLUSION

The results showed that physical violence was a major concern. Many participants were concerned about incidence of violence in their workplace and most disinclined to report violence due to lack of appropriate support and follow-up mechanisms by managers. Provision of appropriate training programs to prevent and manage violence, development of a documenting and reporting system, and identifying and supporting workers-at-risk can lead to minimizing the violence. Moreover, increase of people' awareness about the responsibilities of health care workers should be considered.

Financial support and sponsorship

This article is part of a research project commissioned by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOH) No. 1/16157/t/90/801.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ministry of Health and University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, which enabled us to conduct this study. We are also very grateful to all health professionals who participated in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peek-Asa C, Casteel C, Allareddy V, Nocera M, Goldmacher S, Ohagan E, et al. Workplace violence prevention programs in psychiatric units and facilities. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;23:166–76. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrell G, Cubit K. Nurses under threat: A comparison of content of 28 aggression management programs. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2005;14:44–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0979.2005.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor JL, Rew L. A systematic review of the literature: Workplace violence in the emergency department. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1072–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.St-Pierre I, Holmes D. Managing nurses through disciplinary power: A Foucauldian analysis of workplace violence. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16:352–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray MM. The dark side of the job: Violence in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2007;33:257–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gacki-Smith J, Juarez AM, Boyett L, Homeyer C, Robinson L, MacLean SL. Violence against nurses working in US emergency departments. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39:340–9. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181ae97db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Martino V. Country Case Studies: Brazil, Bulgaria, Lebanon, Portugal, South Africa, Thailand, and an additional Australian study. Geneva: International Labour Office; 2002. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 8]. Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/injury/en/WVsynthesisreport.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magnavita N, Heponiemi T. Workplace violence against nursing students and nurses: An Italian experience. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2011;43:203–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen WC, Sun YH, Lan TH, Chiu HJ. Incidence and risk factors of workplace violence on nursing staffs caring for chronic psychiatric patients in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:2812–21. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6112812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Najafi F, Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Dalvandi A, Ahmadi F, Rahgozar M. Workplace violence against Iranian nurses: A systematic review. J Health Promot Manage. 2014;3:72–85. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahmani A, Atefeh AB, Dadashzadeh A, Namdar H, Akbadi MA. Physical violence in working environments: Viewpoints of EMT'personnel in East Azerbaijan Province. Iranian J Nurs Res. 2009;3:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang LQ, Spector PE, Chang CH, Gallant-Roman M, Powell J. Psychosocial precursors and physical consequences of workplace violence towards nurses: A longitudinal examination with naturally occurring groups in hospital settings. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:1091–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Embree JL, White AH. Concept analysis: Nurse-to-nurse lateral violence. Nurs Forum. 2010;45:166–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2010.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hesketh KL, Duncan SM, Estabrooks CA, Reimer MA, Giovannetti P, Hyndman K, et al. Workplace violence in Alberta and British Columbia hospitals. Health policy. 2003;63:311–21. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(02)00142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng JY, An FR, Xiang YT, Qi YK, Ungvari GS, Newhouse R, et al. Frequency and risk factors of workplace violence on psychiatric nurses and its impact on their quality of life in China. PsychiatryRes. 2013;210:510–4. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rew M, Ferns T. A balanced approach to dealing with violence and aggression at work. Br J Nurs. 2005;14:227–32. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2005.14.4.17609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fallahi Khoshknab M, Oskouie F, Najafi F, Ghazanfari N, Tamizi Z, Ahmadvand H. Psychological Violence in the Health Care Settings in Iran: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2015;4:e24320. doi: 10.17795/nmsjournal24320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fallahi Khoshknab M, Oskouie F, Ghazanfari N, Najafi F, Tamizi Z, Afshani SH, Azadi Gh. The Frequency, Contributing and Preventive Factors of Harassment towards Health Professionals in Iran. IJCBNM. 2015;3:156–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aivazi AA, Tavan H. Prevalence of conceived violence against nurses at educational hospitals of Ilam, Iran, 2012. IJANS. 2015;2:65–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector: Workplace Violence in the Health Sector Country Case Studies Research Instruments Survey Questionnaire. Geneva: International Labor Office, International Council of Nurses, World Health Organization, and Public Services International; 2003. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 10]. International Labor Office, International Council of Nurses, World Health Organization, and Public Services International. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/interpersonal/en/WVquestionnaire.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esmaeilpour M, Salsali M, Ahmadi F. Workplace violence against Iranian nurses working in emergency departments. Int Nurs Rev. 2011;58:130–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.AbualRub RF, Al-Asmar AH. Physical violence in the workplace among Jordanian hospital nurses. J Transcult Nurs. 2011;22:157–65. doi: 10.1177/1043659610395769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasani A, Zaheri M, Abbasi M, Saeedi H, Hosseini M, Fathi M. Incidence Rate of physical and verbal violence inflicted by patients and their companions on the emergency department staff of Hazrate-e-Rasoul Hospital in the fourth trimester of the year 1385. Razi J Med Sci. 2010;16:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gholaamzade-Nikjo R, Sahebi L. Workplace violence on clinical workers in Tabriz educational hospitals. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2012;13:40. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abderhalden C, Needham I, Friedli T, Poelmans J, Dassen T. Perception of aggression among psychiatric nurses in Switzerland. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2002:110–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.106.s412.24.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erkol H, Gökdoğan MR, Erkol Z, Boz B. Aggression and violence towards health care providers-a problem in Turkey? J Forensic Leg Med. 2007;14:423–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talas MS, Kocaöz S, Akgüç S. A survey of violence against staff working in the emergency department in Ankara, Turkey. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2011;5:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rafati Rahimzadeh M, Zabihi A, Hosseini SJ. Verbal and physical violence on nurses in hospitals of Babol University of Medical Sciences. Hayat. 2011;17:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merecz D, Rymaszewska J, Mościcka A, Kiejna A, Jarosz-Nowak J. Violence at the workplace-a questionnaire survey of nurses. Eur Psychiatry. 2006;21:442–50. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang JS, Chen CL, Zhang ZR, Wang L. Incidence and related factors of violence in emergency departments-a study of nurses in southern Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106:748–58. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zampieron A, Galeazzo M, Turra S, Buja A. Perceived aggression towards nurses: Study in two Italian health institutions. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2329–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pich J, Hazelton M, Sundin D, Kable A. Patient-related violence against emergency department nurses. Nurs Health Sci. 2010;12:268–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AbuAlRub RF, Khalifa MF, Habbib MB. Workplace violence among Iraqi hospital nurses. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:281–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koohestani HR, Baghcheghi N, Rezaei K, Abedi A, Seraji A, Zand S. Occupational Violence in Nursing Students in Arak, Iran. Iranian J Epidemiol. 2011;7:44–50. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Tamizi Z, Ghazanfari N, Mehrabani G. Prevalence of workplace violence in psychiatric wards, Tehran, Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2012;15:680–4. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2012.680.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hegney D, Plank A, Parker V. Workplace violence in nursing in Queensland, Australia: A self-reported study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003;9:261–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-172x.2003.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]