Abstract

Background

The potential for malignant transformation varies among pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN) subtypes. Imaging and cyst fluid analysis are used to identify premalignant or malignant cases that should undergo operative resection, but the accuracy of operative decision-making process is unclear. The objective of this study was to characterize misdiagnoses of PCN and determine how often operations are undertaken for benign, non-premalignant disease.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of patients undergoing pancreatic resection for the preoperative diagnosis of PCN was undertaken. Preoperative and pathological diagnoses were compared to measure diagnostic accuracy.

Results

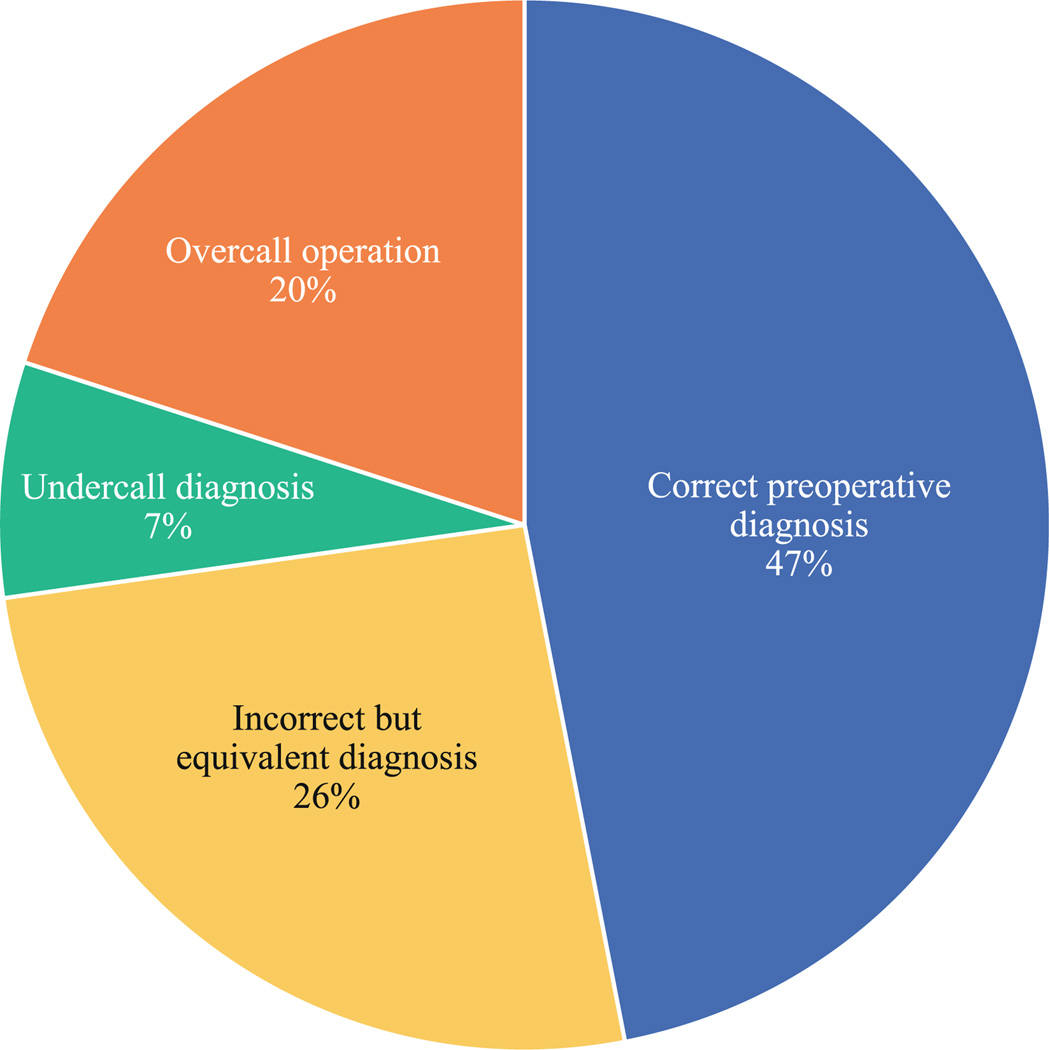

Between 1999 and 2011, 74 patients underwent pancreatic resection for the preoperative diagnosis of PCN. Preoperative classification of mucinous vs. non-mucinous PCN was correct in 74 %. The specific preoperative PCN diagnosis was correct in 47 %, but half of incorrect preoperative diagnoses were clinically equivalent to the pathological diagnoses. The likelihood that the pathological diagnosis was of higher malignant potential than the preoperative diagnosis was 7 %. In 20 % of cases, the preoperative diagnosis was premalignant or malignant, but the pathological diagnosis was benign. Diagnostic accuracy and the rate of undercall diagnoses and overcall operations did not change with the use of EUS or during the time period of this analysis.

Conclusions

Precise, preoperative classification of PCN is frequently incorrect but results in appropriate clinical decision-making in three-quarters of cases. However, one in five pancreatic resections performed for PCN was for benign disease with no malignant potential. An appreciation for the rate of diagnostic inaccuracies should inform our operative management of PCN.

Pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN) are being diagnosed with increasing frequency.1 Despite considerable investigation, their natural history remains unclear. Whereas serous cystadenomas (SC) are benign lesions with a negligible risk of malignant transformation, mucinous PCN including mucinous cystic neoplasms (MC), branch duct-intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN-B), and main duct-intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN-M) harbor variable malignant potential. The ability of marked elevations in cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) to identify mucinous PCN, and the identification of anatomic risk factors for malignancy (cyst size, intracystic mural nodularity, main pancreatic duct involvement), have enabled consensus strategies to guide the identification and management of PCN.2–4

Appropriate selection of patients for operative versus nonoperative management ultimately depends on accurate preoperative PCN classification. To date, the relatively few studies that have retrospectively analyzed the precision of preoperative PCN classification by comparing preoperative diagnoses to definitive post-resection pathological diagnoses suggest that this accuracy may be suboptimal.5–7 We reviewed our institutional experience with patients selected to undergo resection of PCN, and compared preoperative and pathological diagnoses to ask how accurately we classify PCN preoperatively. Which preoperative variables are associated with improvements in diagnostic accuracy? How often is the pathological diagnosis more aggressive than the preoperative diagnosis, and how often are we performing pancreatic resections for benign disease with no likelihood of malignant transformation? We hypothesized that the accuracy of preoperative classification of PCN is imperfect but improving over time with the use of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and cyst fluid analysis; we also hypothesized that diagnostic discordance was of minimal clinical significance, with discrepancies generally being between PCN with potential risks of malignancy (e.g., between IPMN-B and MC).

METHODS

We reviewed our institutional prospective database to identify patients who underwent pancreatectomy at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health between January 1999 and March 2012 for the specific operative indication of PCN; cases undertaken to resect pseudocysts and cases of incidentally diagnosed PCN were excluded. All PCN patients in our institution are evaluated and reviewed in a multidisciplinary clinic and conference with the input of pancreatic surgeons, gastroenterologists, radiologists, pathologists, and medical oncologists. The indication for operative resection in our institution has been the inability to exclude premalignancy or malignancy based on the presence of worrisome anatomic features (mural nodules, upstream pancreatic or biliary ductal obstruction, size >3 cm, interval cyst enlargement) and/or clinical features (weight loss or pain felt to be referable to the PCN). Beginning in 2006, the Sendai international consensus guidelines for management of mucinous PCN2 were explicitly adopted to guide operative decision-making. Categories of PCN diagnosis were defined as SC, MC, IPMN-B, IPMN-M, cystic neuroendocrine neoplasm (NE), solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm (SP), and cystadenocarcinoma (CA). Categories of PCN classification were defined as non-mucinous (SC, NE, SP) or mucinous (MC, IPMN-B, IPMN-M, CA). Hospital records were evaluated to identify a single preoperative diagnosis and the non-mucinous versus mucinous classification determined by the operating surgeon as specified in his preoperative clinic notes or operative dictation. Cases in which a single favored preoperative diagnosis or non-mucinous versus mucinous classification was not clearly documented were classified as indeterminate (IND). Patient characteristics, preoperative radiographic and endoscopic findings, and the date and type of operation were recorded, and all pathological specimens were reexamined by a single pathologist (AGL). To evaluate the accuracy of preoperative diagnosis over time, cases were divided into two eras by date of operation (era 1: 1999–2005; era 2: 2006–2011).

The clinical significance of errant diagnoses was estimated by categorizing PCN diagnoses as benign (SC, pseudocyst (PC), lymphoepithelial cyst (LC)), premalignant (MC, IPMN-B, IPMN-M), or malignant (CA, NE, SP). Preoperative diagnoses were retrospectively scored as undercall diagnoses when the pathological diagnosis was of higher malignant potential than the preoperative diagnosis. Operations were considered overcall operations when the preoperative diagnosis was either premalignant or malignant and the pathological diagnosis was benign.

Comparisons of continuous variables were performed using a t test and comparisons of categorical variables were performed using chi-square analysis using the SPSS statistical package, and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Perioperative characteristics are summarized in Table 1. We identified 74 patients who underwent surgical resection for the preoperative indication of PCN between 1999 and 2011 (29 in era 1 and 45 in era 2). Retrospective review of all individual cases confirmed the presence of at least one criterion for resection based on the Sendai consensus guidelines for all patients with suspected mucinous PCN, including those cases that predated publication of the guidelines in 2006. In addition, resection was undertaken in five cases of suspected SC due to the presence of a worrisome solid component (n = 3), progressive enlargement (n = 1), and associated symptoms (n = 1). The perioperative characteristics that differed between eras were the preoperative use of MRI (p = 0.001), imaging studies performed at our institution (p = 0.024), preoperative use of EUS (p = 0.00001), and the performance of laparoscopic left pancreatectomy (p = 0.014).

TABLE 1.

Perioperative characteristics

| Overall (n = 74) | Era 1 (n = 29) | Era 2 (n = 45) | p (era 1 vs. era 2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range) | 59 years (22–85) | 60 years (25–80) | 59 years (22–85) | NS |

| Female | 76 % | 69 % | 80 % | NS |

| Location in pancreatic head | 36 % | 38 % | 36 % | NS |

| Mean cyst size (range) | 4.2 cm (0.9–19) | 4.5 cm (0.9–16) | 3.9 cm (1.5–19) | NS |

| Intracystic septation(s) | 35 % | 35 % | 36 % | NS |

| Intracystic solid component(s) | 18 % | 14 % | 20 % | NS |

| Cyst enlargement | 24 % | 14 % | 31 % | NS |

| Cyst-related symptom(s) | 42 % | 52 % | 36 % | NS |

| Preoperative CT | 99 % | 100 % | 98 % | NS |

| Preoperative MR | 22 % | 0 % | 36 % | 0.0001 |

| Imaging performed at our institution | 68 % | 52 % | 78 % | 0.024 |

| Preoperative EUS | 65 % | 35 % | 84 % | 0.00001 |

| Atypia/adenocarcinoma in cyst fluid cytologya | 12 % | 22 % | 9 % | NS |

| Mean cyst fluid CEA (range)a | 2622 ng/mL (6–44560) | 821 ng/mL (18–1873) | 2932 ng/mL (6–44560) | NS |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 34 % | 35 % | 31 % | NS |

| Open left pancreatectomy | 38 % | 52 % | 29 % | NS |

| Laparoscopic left pancreatectomy | 23 % | 7 % | 33 % | 0.014 |

| Total pancreatectomy | 4 % | 3 % | 4 % | NS |

| Enucleation | 1 % | 3 % | 0 % | NS |

Bold values indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05)

Among patients who underwent cyst fluid analysis

PCN diagnoses are summarized in Fig. 1. Preoperative diagnoses were MC in 31 %, IPMN in 33 %, CA in 15 %, indeterminate in 12 %, SC in 7 %, and NE in 2 %; pathological diagnoses were MC in 34 %, IPMN in 23 %, CA in 12 %, SC in 19 %, and other in 7 % (2 SP and each of NE, PC, and LC). Preoperative PCN diagnosis was correct in 47 % and preoperative classification of mucinous vs. non-mucinous PCN was correct in 80 %.

FIG. 1.

a Breakdown of preoperative PCN diagnoses. b Breakdown of pathological PCN diagnoses. SC serous cystadenoma, MC mucinous cystic neoplasm, IPMN-B branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, IPMN-M main duct or mixed type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, NE cystic neuroendocrine neoplasm, CA mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, IND indeterminate, SP solid pseudopapillary neoplasm, PC pseudocyst, LC lymphoepithelial cyst

Results of univariate analysis to identify variables associated with accuracy of preoperative PCN diagnosis are summarized in Table 2. The only variables associated with differences in diagnostic accuracy were the surgeon (p = 0.049), PCN location in the pancreatic head (p = 0.041), and the specific preoperative PCN diagnosis (p = 0.041). Distributions of pathological diagnoses for selected preoperative diagnoses are highlighted in Fig. 2a. Whereas a preoperative diagnosis of IPMN-M or SC was likely to be correct, pathological diagnoses were more varied when the preoperative diagnosis was CA, IPMN-B, or MC. Pathological diagnoses in cases with IND preoperative diagnoses were varied and included SC, IPMN-Br, MC, and CA. Preoperative utilization of MRI and EUS and era were not associated with differences in diagnostic accuracy.

TABLE 2.

Univariate analysis of variables associated with differences in accuracy of preoperative PCN diagnosis

| n | Correct preoperative diagnosis (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon | |||

| A | 17 | 65 | |

| B | 17 | 29 | |

| C | 9 | 78 | |

| D | 8 | 38 | |

| E | 18 | 44 | |

| Other | 5 | 20 | 0.049 |

| Patient gender | |||

| Male | 18 | 50 | |

| Female | 56 | 46 | NS |

| Cyst location | |||

| Head of pancreas | 27 | 63 | |

| Other | 47 | 38 | 0.041 |

| Cyst size (cm) | |||

| <3 | 26 | 46 | |

| >3 | 48 | 49 | NS |

| Intracystic septation(s) | |||

| No | 48 | 42 | |

| Yes | 26 | 58 | NS |

| Intracystic solid component(s) | |||

| No | 61 | 46 | |

| Yes | 13 | 54 | NS |

| Enlarging cyst | |||

| No | 56 | 46 | |

| Yes | 18 | 50 | NS |

| Symptomatic cyst | |||

| No | 43 | 56 | |

| Yes | 31 | 36 | NS |

| Cytological atypia/adenocarcinoma | |||

| No | 37 | 51 | |

| Yes | 5 | 10 | 0.039 |

| Preoperative diagnosis | |||

| CA | 11 | 46 | |

| IPMN-M | 5 | 80 | |

| IPMN-B | 19 | 53 | |

| MC | 23 | 48 | |

| SC | 5 | 80 | 0.041 |

| Era | |||

| 1 | 29 | 41 | |

| 2 | 45 | 51 | NS |

| Preoperative MRI | |||

| No | 58 | 41 | |

| Yes | 16 | 69 | 0.088 |

| Imaging performed at our institution | |||

| No | 24 | 38 | |

| Yes | 50 | 52 | NS |

| Preoperative EUS | |||

| No | 26 | 39 | |

| Yes | 48 | 52 | NS |

Bold values indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05)

FIG. 2.

a Distributions of pathological diagnoses for selected preoperative diagnoses. b Distributions of pathological diagnoses for preoperative classification of non-mucinous versus mucinous PCN

Mucinous PCN (MC, IPMN-B, IPMN-M, or CA) represented 78 % of preoperative diagnoses and 74 % of pathological diagnoses. On univariate analysis, only the presence of intracystic septation(s) was associated with differences in accuracy of mucinous versus non-mucinous classification (p = 0.022). Distributions of pathological diagnoses among preoperatively classified non-mucinous versus mucinous PCN are highlighted in Fig. 2b. Whereas preoperative classification of mucinous PCN was correct in 79 % of cases, pathological classification of preoperatively classified non-mucinous PCN cases was more varied. Among patients who underwent preoperative cyst fluid analysis, the association between elevated cyst fluid CEA (>200 ng/mL) and mucinous PCN neared but did not reach significance (p = 0.057).

Preoperatively, invasive malignancy was diagnosed in 13 cases (18 %); pathologically, invasive malignancy was observed in 12 cases (16 %). However, these cases were not very concordant; among the 12 pathologically confirmed cases of malignancy, invasive malignancy was the preoperative diagnosis in only 7 (58 %) based on preoperative biopsy (n = 6) or suspicious clinical and radiographic findings (n = 1). Only 46 % of preoperative diagnoses of invasive malignancy proved correct. The likelihood of identifying occult malignancy not suspected preoperatively was 7 %; among these five cases, the preoperative diagnoses were IND (n = 2), MC (n = 2), and IPMN-M (n = 1). In six cases where invasive malignancy was the preoperative diagnosis based on clinical presentation and/or radiographic appearance, pathological analysis identified SC (n = 3) and MC (n = 3). By univariate analysis, only cyst size ≥3 cm (p = 0.046), presence of symptoms attributable to the PCN (p = 0.011), and abnormal cyst fluid cytology (p = 0.002) were associated with invasive malignancy. Presence of a solid component and cyst enlargement were not associated with invasive malignancy. When examined by multivariate analysis, the only association that remained statistically significant was that between abnormal cytology and invasive malignancy (p = 0.015). These data did not change when either era was examined separately.

A breakdown of diagnostic errors is outlined in Fig. 3. Although the overall rate of accurate preoperative diagnosis was only 47 %, approximately half of incorrect preoperative diagnoses were clinically equivalent to the pathological diagnoses. The rate of undercall diagnoses was 7 %, and the rate of overcall operations was 20 %. The distribution of these diagnostic categories did not change between eras or with the use of preoperative EUS and was no different between surgeons (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Breakdown of diagnostic errors. Undercall diagnosis case in which the pathological diagnosis was of higher malignant potential than the preoperative diagnosis, overall operation case in which the preoperative diagnosis was either premalignant or malignant and the pathological diagnosis was benign

DISCUSSION

Surgical decision-making for patients with PCN is influenced by two opposing vectors: the risk of potential (pre)neoplasia versus and the risk of morbidity and mortality following pancreatic resection. The heavy consequences of these risks mandate that these decisions be made as precisely as possible. Collective, multidisciplinary experiences have led to consensus guidelines for estimating the risk of (pre)neoplasia among PCN.8–18 Although these guidelines are used for treatment planning, the concordance of preoperative and pathological diagnoses in cases selected for operative resection has not been comprehensively measured.5–7,19–22 Moreover, the potential clinical impact of misdiagnoses and misclassifications has not been scrutinized. We therefore sought to characterize the outcomes of cases in which the decision was made to undertake operative resection.

We observed that the preoperative diagnosis matched the pathological diagnosis in only 47 % of cases. Contrary to our hypothesis, accuracy did not improve from era 1 to era 2, and incorporation of EUS into the preoperative evaluation was not associated with improvement in diagnostic accuracy. These findings suggest that EUS and cyst fluid analysis may not add meaningful information beyond clinical cues elicited by history and cross-sectional imaging alone. Alternatively, the absence of diagnostic improvement over time or with the use of EUS may have been due to selection bias. PCN cases presenting in era 2 could have been generally more diagnostically challenging than those presenting in era 1; alternatively, EUS may have been preferentially used for cases eluding diagnostic characterization by cross-sectional imaging alone (and used less frequently in diagnostically straightforward cases). It also is possible that more patients may have been selected for nonoperative observation based on imaging and/or EUS in era 2. Given the limitations of our database, we did not have access to the denominator of patients selected for nonoperative observation based on radiographic and EUS findings. However, we found no differences in the distribution of preoperative and pathological PCN diagnoses or in cyst characteristics between the two eras or between EUS and non-EUS cases (data not shown). Moreover, the rather widespread use of EUS (84 %) may mitigate the impact that selection bias may have had in era 2. Use of MRI increased in era 2; however, choice of imaging (CT vs. MRI) and whether imaging was performed at our institution versus a referring institution did not measurably impact diagnostic accuracy.

The only variables associated with improved accuracy of preoperative PCN diagnosis were surgeon, PCN location in the pancreatic head, and specific preoperative diagnosis. The influence of the surgeon suggests that individual variations in diagnostic ability may exist in the evaluation of PCN. Although such variability might suggest that individual diagnostic accuracy can be improved, we observed no changes in individual diagnostic accuracy between eras (data not shown). Variations in individual diagnostic accuracy could have resulted from differences in referral or practice patterns (i.e., some surgeons may have evaluated or operated on more diagnostically challenging cases than others), but we found no differences in the distribution of preoperative and pathological PCN diagnoses or in cyst characteristics between surgeons (data not shown). Variations in diagnostic accuracy between specific preoperative diagnoses suggest that PCN with distinct anatomic features (IPMN-M and SC) are easier to characterize than PCN with overlapping anatomic characteristics (IPMN-B and MC).

Although the specific preoperative PCN diagnosis proved correct in only one-half of our cases, the clinically important ability to distinguish mucinous from non-mucinous PCN was accurate in three-quarters. We did not identify any novel diagnostic markers for mucinous PCN. Indeed, the only preoperatively assessable variable associated with pathologically confirmed mucinous PCN was the presence of intracystic septation(s). However, its positive predictive value (42 %) was diluted by the high prevalence of septation(s) in two-thirds of pathologically confirmed non-mucinous PCN cases. Although well-established as a diagnostic marker for mucinous PCN, the wide variability of CEA levels within mucinous and non-mucinous PCN was reflected in its suboptimal association with mucinous PCN (p = 0.057).

Invasive malignancy accounted for 18 % of all preoperative diagnosis and 16 % of all pathological diagnoses. However, the correlation between these cases was poor, as only half of the preoperative diagnoses of invasive malignancy proved correct. We did not identify any novel markers for the presence of cancer; although cyst size ≥3 cm, presence of symptoms attributable to the PCN, and evidence of atypia or adenocarcinoma on cyst fluid cytology were all associated with the presence of invasive malignancy, their positive predictive values were suboptimal at 21, 29 and 60 % respectively.

Although precise preoperative PCN diagnosis may be suboptimal, overlap in the clinical significance of some PCN diagnoses mitigates the practical impact of this inaccuracy. In fact, although only half of all preoperative diagnoses were accurate, three-quarters of all preoperative diagnoses were clinically equivalent to pathological diagnoses when we classified PCN into benign, pre-malignant, and malignant categories. In the remaining one-quarter of cases, the preoperative diagnosis was three times more likely to be an overcall (i.e., more aggressive than the pathological diagnosis) than an undercall. To some extent, this bias toward conservatism should be expected, as surgical oncologists are likely to resolve uncertainty by erring toward overtreatment rather than undertreatment. In our experience, one in five resections for PCN was performed for what was eventually determined to be benign, non-premalignant disease (serous cystadenoma, pseudocyst, lymphoepithelial cyst). In light of the risks associated with pancreatectomy, this rate of overtreatment may appear excessive; however, to define an appropriate threshold rate of overtreatment (i.e., false-positive diagnoses), it must be measured against the rate of undertreatment (i.e., false-negative diagnoses). In our experience, the likelihood of identifying an unexpected invasive PCN-related malignancy was 7 %. Because our dataset was limited to those patients who underwent surgical resection, it is possible that other cases of occult malignancy may have been missed; however, recent longitudinal studies suggest that the long-term incidence of malignancy in PCN patients subjected to long-term surveillance is only 2–3 %.1,22 Our institutional experience suggests that current diagnostic capabilities and conventional surgical decision-making strategies result in approximately three cases of diagnostic overestimations of cancer risk (20 % in our series) for every one case of underestimated risk (7 % in our series). As we continue to critique our collective experiences in the surgical management of PCN, close attention to these measures may help to define the optimal threshold of surgical aggressiveness needed to avoid missed diagnoses of cancer.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gajoux S, Brennan MF, Gonen M, et al. Cystic lesions of the pancreas: changes in the presentation and management of 1,424 patients at a single institution over a 15-year time period. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17–32. doi: 10.1159/000090023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khalid A, Brugge W. ACG practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2339–2349. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bose D, Tamm E, Liu J, et al. Multidisciplinary management strategy for incidental cystic lesions of the pancreas. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung KK, Ross WA, Evans D, et al. Pancreatic cystic neoplasm: the role of cyst morphology, cyst fluid analysis, and expectant management. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2818–2824. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donahue TR, Hines OJ, Farrell JJ, et al. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: results of 114 cases. Pancreas. 2010;39:1271–1276. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181e1d6f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Correa-Gallego C, Ferrone CR, Thayer SP, et al. Incidental pancreatic cysts: do we really know what we are watching? Pancreatology. 2010;10:144–150. doi: 10.1159/000243733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewandrowski KB, Southern JF, Pins MR, et al. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cysts. A comparison of pseudocysts, serous cystadenomas, mucinous cystic neoplasms, and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1993;217:41–47. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199301000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen PJ, Jaques DP, D’Angelica M, et al. Cystic lesions of the pancreas: selection criteria for operative and nonoperative management in 209 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:970–977. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryu JK, Woo SM, Hwang JH, et al. Cyst fluid analysis for the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cysts. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:100–105. doi: 10.1002/dc.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brugge WR, Lweandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330–1336. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvia R, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Bassi C, et al. Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: clinical predictors of malignancy and long-term survival following resection. Ann Surg. 2004;239:678–685. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124386.54496.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sahani DV, Kadavigere R, Saokar A, et al. Cystic pancreatic lesions: a simple imaging-based classification system for guiding management. Radiographics. 2005;25:1471–1484. doi: 10.1148/rg.256045161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Waaij LA, van Dullemen HM, Porte RJ. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions: a pooled analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:383–389. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)01581-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crippa S, Salvia R, Warshaw AL, et al. Mucinous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas is not an aggressive entity: lessons from 163 resected patients. Ann Surg. 2008;246:571–579. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31811f4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang JY, Kim SW, Lee SE, et al. Treatment guidelines for branch duct type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: when can we operate or observe? Ann Surg. Oncol. 2008;15:199–205. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9603-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ceppa EP, De la Fuente SG, Reddy SK, et al. Defining criteria for selective operative management of pancreatic cystic lesions: does size really matter? J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:236–244. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cizniger S, Turner B, Bilge AR, et al. Cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen is an accurate diagnostic marker of pancreatic mucinous cysts. Pancreas. 2011;40:1024–1028. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31821bd62f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Procacci C, Biasiutti C, Carbognin G, et al. Characterization of cystic tumors of the pancreas: CT accuracy. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23:906–912. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199911000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curry CA, Eng J, Horton K, et al. CT of primary cystic pancreatic neoplasms: can CT be used for patient triage and treatment? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:99–103. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.1.1750099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Bernsinger C, et al. Interobserver agreement among endosonographers for the diagnosis of neoplastic versus non-neoplastic pancreatic cystic lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:59–64. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen PJ, D’Angelica M, Gonen M, et al. A selective approach to the resection of cystic lesions of the pancreas: results from 539 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2006;244:572–582. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000237652.84466.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]