Abstract

Plant disease resistance genes (R-genes) play a critical role in the defense response to pathogens. Barley is one of the most important cereal crops, having a genome recently made available, for which the diversity and evolution of R-genes are not well understood. The main objectives of this research were to conduct a genome-wide identification of barley Coiled-coil, Nucleotide-binding site, Leucine-rich repeat (CNL) genes and elucidate their evolutionary history. We employed a Hidden Markov Model using 52 Arabidopsis thaliana CNL reference sequences and analyzed for phylogenetic relationships, structural variation, and gene clustering. We identified 175 barley CNL genes nested into three clades, showing (a) evidence of an expansion of the CNL-C clade, primarily due to tandem duplications; (b) very few members of clade CNL-A and CNL-B; and (c) a complete absence of clade CNL-D. Our results also showed that several of the previously identified mildew locus A (MLA) genes may be allelic variants of two barley CNL genes, MLOC_66581 and MLOC_10425, which respond to powdery mildew. Approximately 23% of the barley CNL genes formed 15 gene clusters located in the extra-pericentromeric regions on six of the seven chromosomes; more than half of the clustered genes were located on chromosomes 1H and 7H. Higher average numbers of exons and multiple splice variants in barley relative to those in Arabidopsis and rice may have contributed to a diversification of the CNL-C members. These results will help us understand the evolution of R-genes with potential implications for developing durable resistance in barley cultivars.

Keywords: pathogen resistance, NBS-LRR, CNL, barley, grass phylogenetics

Introduction

Plants have evolved complex signaling pathways for pathogen detection and defense response.1 Lacking an adaptive immunity and cell-transporting circulatory system, plant resistance to pathogens depends upon innate immunity that utilizes molecular signaling to initiate local and systemic responses.2 Resistance genes (R-genes) encode proteins that detect pathogens.3,4 Plant immunity can be divided into two types: pathogen- associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI).2,5 PAMPs are pathogen structural molecules, such as bacterial flagellin, peptidoglycan, and fungal chitin, that the plant’s immune system perceives through membrane-localized, receptor-like kinases called pattern recognition receptors, which elicit a response.6,7 In contrast, ETI involves the interaction between specific pathogen effectors and NBS-LRR receptors within the cell.5 Resistance responses vary widely and act in limiting the spread and effectiveness of the pathogen3 including the following: (1) causing localized death of infected tissue through hypersensitive response,8 (2) promoting hostile conditions for pathogens such as hydrogen peroxide production in an oxidative burst,9 and (3) fortifying cell walls to strengthen the physical barrier between pathogens and the plant protoplasm.10 Resistance responses are expensive for the cell11; therefore, in the absence of a pathogen, diverse control factors are mobilized,12 including salicylic acid production for localized and systemic resistance,13,14 WRKY transcription factors,15 and silencing through micro-RNA.16

Several models have been proposed to describe the mechanism of host–pathogen relationships. The gene-for-gene model involves direct interaction between a single pathogen avirulence gene and a plant R-gene.17 Additionally, there is evidence of indirect interaction as described in the guard model, where R-proteins bind with or guard particular target proteins, activating a response when the guarded protein is cleaved or modified by a pathogen.18,19 Similar to the guard model, the decoy model describes specific decoy proteins that mimic unguarded pathogen effector targets, forming a complex with effectors that is perceived by NBS-LRR R-proteins.20 With increasing understanding of molecular interactions between the pathogen and host, the zigzag model was proposed to describe coevolution of plant R-genes and pathogen effectors.2 In this model, the pathogen evolves effectors to reduce the effectiveness of the plant’s PTI response, and the plant responds to these newly evolved effectors by developing receptors that initiate ETI.2 Intense selection pressures from pathogens cause R-genes to evolve rapidly through several mechanisms, including recombination and transposable elements.4,21,22 However, R-genes can also be removed from the genome through loss of lineages and deficient duplications.23

R-genes have been recently classified into eight major groups: (1) Toll interleukin receptor, Nucleotide-binding site, Leucine-rich repeat (TIR-NBS-LRR or TNL); (2) Coiled-coil, NBS, LRR (CC-NBS-LRR or CNL), (3) LRR trans-membrane domain (LRR-TrD); (4) LRR-TrD-kinase; (5) LRR-TrD protein degradation domain proline-glycine-serine-threonine (LRR-TrD-PEST); (6) TrD-CC; (7) TNL-nuclear localization signal amino acid domain (TNL-NLS-WRKY); and (8) enzymatic genes.24 Among these groups, the NBS-LRR (TNL and CNL) genes form the largest group and respond to various pests and pathogens.25 The NBS-LRR genes are highly variable,25,26 but their NBS region contains several conserved motifs that can be traced back to early land plant groups.27 The N-terminal region of the protein contains either a TIR or a CC region, the former being restricted to only dicot species.26 The NBS contains a highly conserved Nucleotide-Binding domain shared by Apaf-1, resistance gene products, and CED-4 (NB-ARC),28 whereas the C-terminal LRR is a highly variable region that can bind to many different molecules.7,29 The CNL genes have been identified in the genomes of many plant species: 52 in Arabidopsis,26 159 in rice,30,31 188 in soybean,30,32 203 in grape,33 65 in potato,34 94 in common bean,35 177 in alfalfa,36 six in papaya,37 and 18 in cucumber.38 Recent studies have shown that CNL genes are effective at resistance to the devastating Ug99 stem rust strain in wheat.39,40 In the present study, we explored the recently available barley genome41 to understand the diversity and evolution of CNL genes.

Cultivated barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) is a grass family (Poaceae) member that was domesticated approximately 10,000 years ago42 and is now a major cereal crop.43 Even before genomic information was available, the use of barley cultivars with R-gene Rpg1 in 1942 greatly reduced the loss of barley yield due to stem rust, Puccinia graminis, in the Midwestern United States and Canada.44,45 Additionally, barley cultivars containing the gene Rph20 are resistant to barley leaf rust (pathogen: Puccinia hordei), which otherwise causes up to 62% crop loss.46,47 It has been shown that the recessive barley mlo mutant allele confers broad-spectrum resistance to powdery mildew (pathogen: Erysiphe graminis f. sp. hordei),48,49 but the presence of these mlo mutant alleles also increases susceptibility to Ramularia Leaf Spot (RLS).22 Genes within the mildew locus A (MLA), some of which are CNL, also play a role in resistance to powdery mildew and were formed through duplication, inversion, and insertion over a period of greater than seven million years.50 It has been hypothesized that many variants of MLA are different alleles rather than separate genes.51 In a recent study, higher nucleotide diversity was found in wild barley samples relative to that in the cultivated samples.52

The objectives of this research project were to identify CNL R-genes in the barley genome and elucidate their evolutionary relationships. This in silico analysis aims at comparing barley CNL genes with their orthologs in rice and Arabidopsis thaliana. With barley and related species making up a significant portion of the staple food supply, analyses that would potentially lead to more pathogen-resistant cultivars make a significant contribution to agriculture. Wheat, another member of the same family, may contain many similar R-gene pathways and barley resistance may be conferrable to the wheat cultivars.

Materials and Methods

CNL gene identification

Barley CNL gene identification followed methods used in Arabidopsis26 and soybean.53 Barley protein sequences were accessed through the Ensembl Genomes database.54 Arabidopsis CNL genes, as identified and classified by Meyers et al.26, were obtained from Phytozome,55 and their orthologs in rice were obtained, as confirmed in the study by Benson.31 Fifty-two Arabidopsis CNL genes were used as reference sequences to explore orthologs in the barley genome (62,236 analyzed protein sequences), by aligning the sequences in the program ClustalW56 and constructing a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) using HMMER version 3.1b257 at a stringency of 0.05. Further selection involved identification of NB-ARCs using the database Pfam,58 accessed through InterProScan.59 Genes containing NB-ARCs were then aligned using ClustalW, integrated within the program Geneious.60 A second HMM profile was constructed to use these barley NB-ARC-containing proteins to perform a reiterative search of the genome with a stringency of 0.001. InterProScan59 was then used to identify the protein sequences with both an NB-ARC and a DiseaseResist region. MEME analysis,61 set to display the 20 most prevalent motifs, was used to identify protein sequences with P-loop, Kinase-2, and GLPL regions, the diagnostic motifs of CNL genes.

Phylogenetic analysis

NB-ARCs were extracted from the protein sequences identified by the MEME search. These sequences were aligned using ClustalW integrated within the program Geneious. The protein sequences were imported along with the original Arabidopsis genes and their orthologs in rice for phylogenic comparison. An evolutionary model for the CNL amino acid sequences was determined using a maximum-likelihood model test function in the program MEGA 6.0,62 which identified JTT+G+I as the best substitution model. This model was used to construct a maximum-likelihood tree with 100 bootstrap replicates.

Gene structural variation, clustering, and Ks analysis

Information on location and exon size was obtained from Ensembl Genomes, which was uploaded into the program Fancy gene v1.463 to generate an exon map. Entire chromosome sequences were accessed through Ensembl Genomes and imported into the program Geneious. A genomic map to visualize gene clustering was generated by matching gene locations with their respective chromosomes, along with centromere locations.41 Nucleotide intervals between genes on each chromosome were determined in order to quantify any clustering following the study by Jupe et al.64 Accessions were grouped into clades according to their nesting pattern. Coding sequences were downloaded from Ensembl Genomes to estimate the nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site (Ka) and synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks) values, and Ka/Ks ratios were calculated using the program DnaSP 5.10.1.65 Average Ks values were used to infer the relative time of duplication events.

Results

Identification of CNL genes

We identified 175 CNL genes in the barley genome (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1 for the complete phylogenetic tree, and Supplementary Table 1 for all identified accessions and clade information). Initial HMM analysis of the 62,236 barley protein sequences resulted in 982 orthologous sequences when using the 52 Arabidopsis CNL reference sequences and a stringency of 0.05. InterProScan integrated into the program Geneious was used to identify 908 sequences with Nucleotide- Binding domain shared by Apaf-1, resistance gene products, and CED-4 regions (NB-ARCs). Using these 908 putative barley sequences, the reiterative HMM analysis against the genome at a stringency of 0.001 yielded 950 protein sequences in barley. Using InterProScan, we identified 654 of the 950 barley genes as containing both NB-ARC and DiseaseResist regions. All splice variants were removed, yielding 233 unique NBS-LRR genes, 175 of which contained the signature motifs: P-loop, Kinase-2, and GLPL (Supplementary Fig. 2).

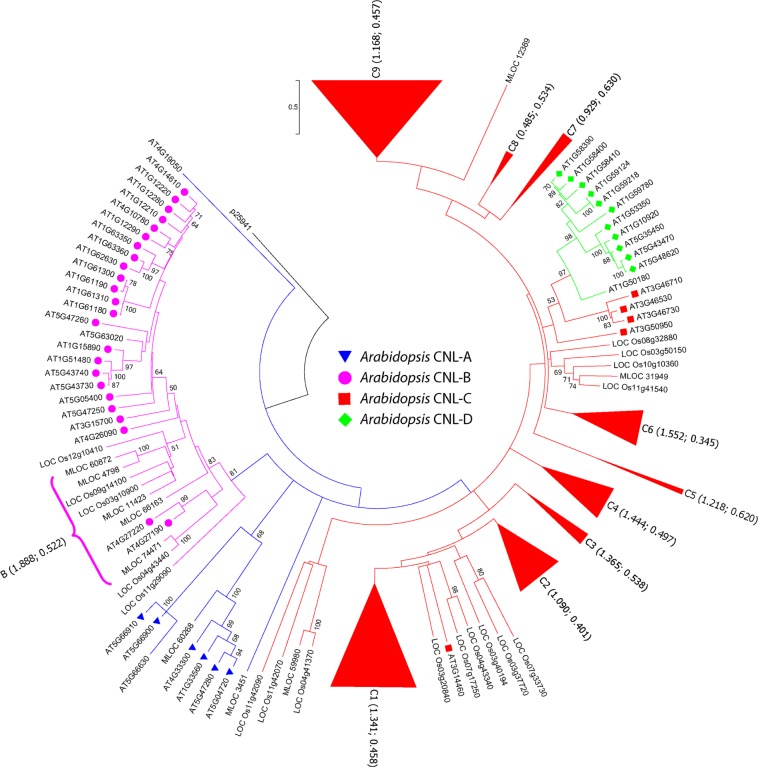

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the CNL genes from H. vulgare (MLOC), Arabidopsis (AT), and Oryza sativa (LOC). The maximum-likelihood tree was constructed using the JTT+G+I model with 100 bootstrap replicates. Arabidopsis CNL-A, CNL-B, CNL-C, and CNL-D groups are represented as blue triangles, pink circles, red squares, and green diamonds, respectively. The tree was rooted using outgroup p25941 as used in Arabidopsis.26 CNL-C clades were collapsed to increase readability (for the complete tree, see Supplementary Fig. 1), and the list of genes can be found in Supplementary Table 1. The Ks values and Ka/Ks ratios are shown in parentheses following the clade name, first Ks and then Ka/Ks ratio. The collapsed clades contain only barley and rice genes with the exception of clades C2 and C6, containing Arabidopsis orthologs AT3G14470 and AT3G07040, respectively.

Phylogenetic relationships

Phylogenetic relationships of barley CNL genes and their orthologs in Arabidopsis are shown in Figure 1 (also in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Among the four clades previously reported in dicot species,26,31 CNL-D is completely absent in barley. The vast majority of the barley CNL genes (168 of the 175 members) belong to the clade CNL-C. Very few members of the CNL-A (two members) and CNL-B clades (five members), as well as the large amount of the CNL-C genes in barley, were consistent with those in rice, but diverse from Arabidopsis (Fig. 1). The orthologs in rice and barley show a high degree of interspecific nesting with a diversified CNL-C clade and complete absence of CNL-D members. Basal support for CNL-C is weak but leaf branches with specific gene relationships are strongly supported (BS >90%). Identification of MLA genes using BLAST within the Ensembl Genomes database showed that MLOC_10425 and MLOC_66581 are the likely accession names for many MLA sequences (Fig. 2).

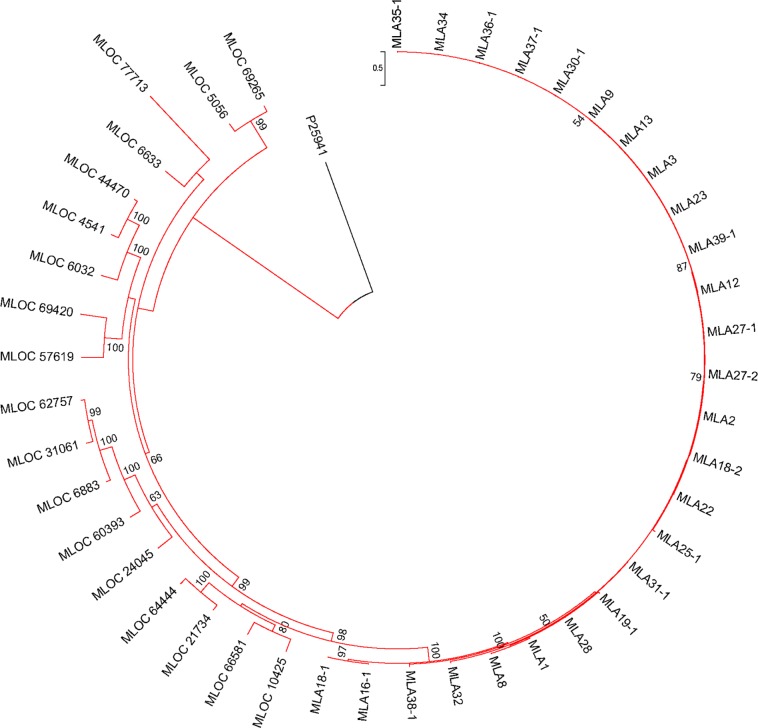

Figure 2.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis of MLA accessions and selected barley CNL-C9 gene members using the JTT+G+I model with 100 bootstrap replicates. The tree was rooted using outgroup p25941 as previously used in Arabidopsis.26

MEME analysis, gene clustering, and structural variation

Conserved motifs visualized through MEME analysis show structural differences between the NB-ARC regions of various barley CNL clades (Supplementary Fig. 2). The P-loop, Kinase-2, and GLPL motifs are present in all genes, and Resistance Nucleotide-Binding Site (RNBS) A, B, and C motifs are present in 165, 172, and 151 members, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). Exon–intron analysis shows that CNL genes are composed of an average of 3.34 exons, ranging from one exon in accession MLOC_6570 to 12 exons in MLOC_10066 (see Supplementary Fig. 3). Of the 175 genes, 30, 46, 26, and 35 had one, two, three, and four exons, respectively; thus, over 78% of the genes were found to contain one to four exons.

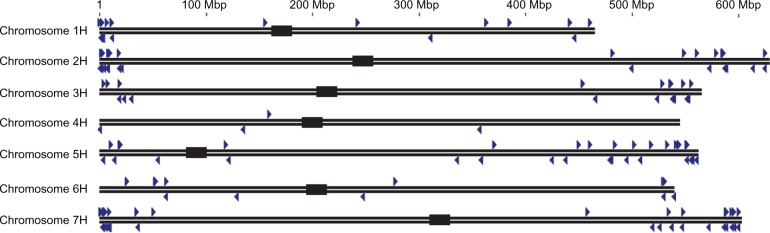

Gene locations on each chromosome were visualized to show CNL gene clustering (Fig. 3), which is defined as: (1) genes within a 200 kb sliding window and (2) fewer than eight other genes between the beginning and end of the cluster. Using these criteria, 15 gene clusters were identified (Table 1). Genes tended to be located in the extra-pericentromeric regions of chromosomes (Fig. 3). Each chromosome except chromosome 4H contained at least one cluster, and 10 of the 15 clusters were composed of only two genes, as shown in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the CNL genes on the chromosomes of barley (N = 7). The black lines and the blue arrows represent chromosomal length and gene location/orientation, respectively. Black rectangles indicate the centromere positions on each chromosome.

Table 1.

CNL gene clusters in the barley genome: 15 clusters containing 39 genes were identified using a sliding window of 200 kb and eight open-reading frames (ORFs).

| CLUSTER | CLUSTERED GENES | KS VALUE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1_1 | MLOC_66596 (C2) | MLOC_5818 (C6) | MLOC_3117 (C2) | 1.435 | ||

| 1_2 | MLOC_70559 (C1) | MLOC_73882 (C7) | 1.753 | |||

| 1_3 | MLOC_767 (C9) | MLOC_53251 (C9) | MLOC_70910 (C9) | MLOC_69663 (C6) | 1.229 | |

| 2_1 | MLOC_44743 (C1) | MLOC_24729 (C1) | 0.194 | |||

| 2_2 | MLOC_66581 (C9) | MLOC_10425 (C9) | 0.520 | |||

| 2_3 | MLOC_4541 (C9) | MLOC_65574 (C6) | 1.443 | |||

| 2_4 | MLOC_76088 (C1) | MLOC_5583 (C1) | 0.579 | |||

| 3_1 | MLOC_56904 (C4) | MLOC_56905 (C4) | 0.217 | |||

| 5_1 | MLOC_12201 (C1) | MLOC_64708 (C9) | MLOC_64709 (C9) | 0.880 | ||

| 6_1 | MLOC_38183 (C9) | MLOC_76360 (C1) | 2.622 | |||

| 6_2 | MLOC_11605 (C1) | MLOC_10242 (C1) | 0.392 | |||

| 6_3 | MLOC_79526 (C9) | MLOC_67477 (C9) | 0.293 | |||

| 7_1 | MLOC_57007 (C9) | MLOC_78491 (C2) | MLOC_4344 (C9) | MLOC_4343 (C9) | MLOC_10643 (C1) | 1.249 |

| 7_2 | MLOC_11112 (C8) | MLOC_75786 (C9) | MLOC_30912 (C8) | MLOC_72805 (C6) | 1.353 | |

| 7_3 | MLOC_6883 (C9) | MLOC_31061 (C9) | 0.163 |

Note: CNL clades for each gene are included in parentheses and Ks values are included for each individual cluster.

Ks values

Synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks values) are often used as a proxy for inferring duplication events, so we used Ks values in inferring relative age of the CNL gene clusters (Table 1). Average Ks values were highest for CNL-B members and lowest for the CNL-C8 members (Fig. 1). All average Ka/Ks ratios were less than 1, indicating a prevalence of purifying selection. Functional homologs for the identified barley genes were compiled and compared with results from the phylogenetic analysis (Table 2). Using this information, instances of genomic expansions as well as reductions were inferred.

Table 2.

CNL orthologs of barley, rice, and Arabidopsis with associated pathogens.

| BARLEY ACCESSION | RICE HOMOLOG | ARABIDOPSIS HOMOLOG | SYNONYM | PATHOGEN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLOC_55575, MLOC_56324, MLOC_67526, MLOC_51950, MLOC_6570, MLOC_20874, MLOC_34944, MLOC_5818, MLOC_69663, MLOC_77773, MLOC_1192, MLOC_72805, MLOC_65574, MLOC_1818, MLOC_64033, MLOC_16581, and MLOC_56093 | LOC_Os06g22460, LOC_Os06g30430, LOC_Os08g09430, LOC_Os12g31620, LOC_Os07g08890, LOC_Os08g16070, LOC_Os02g09790, LOC_Os11g35580, LOC_Os08g16120, LOC_Os11g12000, and LOC_Os11g12340 | AT3G07040 | RPM1 | Pseudomonas syringae77 |

| MLOC_31949 | LOC_Os08g32880, LOC_Os03g50150, LOC_Os10g10360, and LOC_Os11g41540 | AT3G50950 | ZAR1 | Pseudomonas syringae89 |

| MLOC_74471, MLOC_66163, MLOC_11423, MLOC_60872, and MLOC_4798 | LOC_Os12g10410, LOC_Os11g29090, LOC_Os09g14100, LOC_Os03g10900, and LOC_Os04g43440 | AT1G12210 AT4G26090 AT1G12220 AT1G12280 |

RFL1 RPS2 RPS5 SUMM2 |

Pseudomonas syringae19,90–92 |

| MLOC_60268 | – | AT1G33560 AT4G33300 AT5G04720 AT5G47280 |

ADR1 ADR1-L1 ADR1-L2 ADR1-L3 |

Peronospora parasitica and Erysiphe cichoracearum78 |

| MLOC_31949 | LOC_Os08g32880, LOC_Os03g50150, LOC_Os10g10360, and LOC_Os11g41540 | AT3G46530 AT3G46710 AT3G46730 |

RPP13 RPP13-like RPP13-like |

Peronospora parasitica93,94 |

| MLOC_57619, MLOC_69420, MLOC_58258, and MLOC_1443 | LOC_Os07g19320, LOC_Os11g15500, and LOC_Os11g37740 | – | Yr10 | Puccinia striiformis95 |

| MLOC_44141 | LOC_Os05g34230 and LOC_Os04g02110 | – | Rga3 | Magnaporthe oryzae96 |

| MLOC_66596 | LOC_Os01g25740, LOC_Os01g25810, and LOC_Os03g63150 | – | Pm3 | Blumeria graminis97 |

| MLOC_4581 | LOC_Os02g16270 and LOC_Os02g16330 | – | Xa1 | Xanthomonas oryzae98 |

| MLOC_67378 and MLOC_10643 | LOC_Os01g57310 | – | Rp1 | Puccinia sorghi99 |

Discussion

Phylogenetic analysis and evidence of duplications

Phylogenetic analysis of the CNL protein sequences from barley and Arabidopsis showed a high level of tandem duplications within each species. Barley R-genes were nested as expected within the CNL-A, CNL-B, and CNL-C clades with their orthologs in Arabidopsis, concurring with the previous findings in rice31 and Aegilops tauschii.66 We observed fewer members of CNL-A and CNL-B, and complete absence of CNL-D in barley relative to that in Arabidopsis. Using comprehensive phylogeny of flowering plants67 as a reference, we infer that Arabidopsis has experienced a reduction in CNL-C and expansions in CNL-A, CNL-B, and CNL-D. In a recent analysis of CNL genes in soybean (Glycine max),32 a similar expansion in the CNL-C clade was observed. In contrast to CNL genes in soybean, we found a sharp reduction in CNL-A and CNL-B, and absence of CNL-D, in both barley and rice, which may be common in other grass species as well. Phylogenetic analysis of CNL genes of barley with rice (a model monocot68 with a more recent common ancestor69) showed more interspecific nesting patterns than with Arabidopsis (Fig. 1). Existing differences in R-gene diversity, structure, and evolutionary rates across these species may reflect phylogenetic constraints and species-specific evolutionary history.70

Closely related genes within the same gene cluster in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1 and Table 1) show strong evidence of gene duplication events. Despite the huge genome size (5.1 Gb) of barley, there are numerous closely located CNL genes and their clusters that diversified through tandem duplications. One of the most striking examples of tandem duplication involves MLOC_24729 and MLOC_44743 genes, which are only 113 bases apart and are 69.5% identical (528 of 760 sites). The gene accessions MLOC_19475, MLOC_58383, MLOC_44175, and MLOC_12318 are closely related and form their own clade (Fig. 1), with three of these genes located within a 2.24 Mb segment of chromosome 7H, another instance of tandem duplication. The fourth gene in the same clade, MLOC_12318, is located on chromosome 2H, indicating that it resulted from segmental duplication. Similar duplication events have been reported in other plant genomes.71 Overall variation within R-genes is attributed to duplications, recombination, and diversifying selection,25 with whole-genome duplications lessening selective pressures and allowing for diversification, as seen in the soybean genome.72 Increased diversity of R-genes may provide barley with a selective advantage even though maintenance of R-genes during low pathogen exposure might prove very costly as suggested in literature.73 While not residing within a technically defined cluster in barley, many genes are likely formed by gene duplication events, the origin of which could be traced to a common ancestor gene. The genes MLOC_11112, MLOC_30912, and MLOC_15443 form their own clade, with MLOC_30912 basal to the other two. MLOC_11112 and MLOC_30912 are clustered on chromosome 7H, likely formed by tandem duplication. The third gene, MLOC_15443, is approximately 1 Mb upstream of the other two, a possible instance of segmental duplication. Another example is a five-gene subclade (MLOC_66610, MLOC_66596, MLOC_19284, MLOC_68128, and MLOC_3117; BS 78%) in which all five genes are located within a 2.1 Mb section of chromosome 1H, likely to have arisen through gene duplication. It has been shown that R-genes can cluster in larger regions that do not fall within the defined criteria (ie, with the narrow sliding window) of a cluster.74 In Medicago, superclusters have been identified in which a single-chromosome arm contains a large percentage of the genome’s R-genes.36 Zhou et al.30 suggest that duplications of diversely clustered R-genes could explain the frequent and dissimilar duplications.

Ks values have been used to infer the history of duplication events within a genome, especially when analyzing genome duplications or polyploidy.75,76 The barley CNL-B clade has a higher average Ks value than any CNL-C subclade, suggesting recent expansion of CNL-C members in grasses (see Fig. 1). While average Ka/Ks values for each CNL-C clade were <1 indicating purifying selection, 23 individual pairwise values were >1, 15 of those being from CNL-C9. This indicates that while the majority of the identified genes are undergoing purifying selection, a few genes are undergoing positive selection. These Ks values can also give insight into the clustered genes that arise from duplications. For instance, cluster 3_1, composed of MLOC_56904 and MLOC_56905, has a very low Ks value of 0.217, indicating a recent duplication event. Since rice only has one paralog to these two sequences, LOC_Os01g05620 (Fig. 1), the duplication event likely happened after the split of rice and barley lineages. A similar case is shown by MLOC_44743 and MLOC_24729 (cluster 2_1), which have the Ks value of 0.194 and do not have a close paralog in rice, suggesting more recent evolution after rice and barley split. The same happens with cluster 7_3 (MLOC_6883 and MLOC_31061) with a low Ks value of 0.163. From this information, it can be inferred that cluster 3_1 formed first, followed by cluster 2_1, and finally 7_3.

Arabidopsis and rice homologs in barley

Looking more closely at the gene duplications and expansions within the barley genome, a species-specific history of pathogen load can be inferred. Arabidopsis gene AT3G07040 is functionally known as RPM1, an NBS-LRR gene that recognizes either the AvrRpm1 or AvrB type III effectors of Pseudomonas syringae, conferring resistance through a hypersensitive response.77 As shown in Figure 1 and summarized in Table 2, barley contains 17 homologs (clade CNL-C6) of RPM1, what we infer to be a large expansion. It is possible that monocots faced a heavy P. syringae load during their evolutionary history, perhaps both before and after barley and rice diverged, since rice contains only 11 RPM1 homologs (Table 2). Another possibility is that Arabidopsis experienced a reduction through pseudogenization. In some other cases, the barley genome contains fewer R-genes than Arabidopsis. The Arabidopsis ADR1 genes (AT1G33560, AT4G33300, AT5G04720, and AT5G47280) are involved in the resistance response to Peronospora parasitica and Erysiphe cichoracearum.78 The barley genome contains only one homolog (ie, MLOC_60268) for these four genes in Arabidopsis. The same occurs with RPP8 and RPP13 where many Arabidopsis gene members do not have any homologs in barley. Barley and rice appear to differ in the number of ZAR1, RPP13, and ADR1 homologs, with barley’s single ADR1 homolog not being represented in the rice genome. There are also no barley homologs for AT1G10920 (LOV1 – CNL-D), which causes susceptibility to Cochliobolus victoriae.79

The MLA genes in barley confer resistance to powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis f. sp. hordei).80 We have identified many variants of MLA in our analysis (see Fig. 2). Two CNL-C9 gene members, MLOC_66581 and MLOC_10425, are highly similar to many different MLA sequences, with MLOC_66581 being a gene that most likely responds to powdery mildew. A BLAST search using MLOC_66581 and MLOC_10425 within the Ensembl Genomes database reveals that these two genes have the highest sequence identity to all MLA sequences. Seeholzer et al.80 identified two functional MLA genes, MLA27 and MLA18, that both correspond to MLOC_66581 and MLOC_10425 accessions, respectively. As shown in Figure 2, these genes nested close to the MLA sequences, along with MLOC_64444 and MLOC_21734, which would also be closely related to the MLA genes. Thus, our results support the previous predictions by Shen et al.51 and Seeholzer et al.80 that many MLA variant sequences are alleles rather than separate genes.51,80

MLOC_60268 and MLOC_3451 are the only barley genes that nest with Arabidopsis CNL-A, with high bootstrap support. This shows that these two genes represent current CNL-A members in barley and are likely to have existed before the evolutionary split between monocot and dicot plants, between 200 and 140 million years ago.69,81 Accession MLOC_3451 shows most homology to the Apoptotic Protease-Activating Factor 1 (APAF1) from Triticum urartu, contributor of wheat’s A-genome.82 The similarity is not partial; entire protein sequence alignment shows that the sequences are 96.3% similar (1002 identical sites out of 1040). The presence of APAF1 would be expected since hypersensitive response involves an apoptosis-like cell death to prevent the spread of a pathogen. Therefore, CNL-A members in barley are predicted to contribute in hypersensitive response.

Gene structure and genomic content

Since there is no strict correlation between CNL gene content and genome size, a reasonable prediction of barley’s CNL gene content could range from a few dozen members to a several hundred. Two earlier studies in barley reported 50 CNL genes45 and 191 NBS-LRR genes.41 While the rice and barley genomes have vastly different sizes, 420 Mb and 5.1 Gb, respectively,41,83 the genome-wide CNL diversity is rather similar, 159 and 175 genes, respectively. The P-loop, Kinase-2, and GLPL motifs are highly conserved in both species30 and the RNBS A, B, and C motifs (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2) are also prevalent and conserved within the CNL genes.26,30

The CNL genes in barley showed a higher number of exons (3.34 exons per gene; Supplementary Fig. 3) than Arabidopsis and rice, with Arabidopsis genes generally consisting of one exon each26 and rice averaging 2.1 exons per gene.31 The higher number of exons per gene in barley could enable a more variable response to pathogens through multiple splice variation. Since many of the 982 initially identified protein sequences were variants of the same genes, it is possible that barley has used multiple splicing patterns to vary its pathogen-response proteins. It has been shown that NBS-LRR genes go through alternative splicing in Arabidopsis,84 and ratios of different transcripts are required for a resistance response.85

While the number of exons per gene is higher than other species, the amount of CNL gene clustering is lower in barley, where only 39 of 175 CNL genes form 15 gene clusters (Fig. 3 and Table 1). In Arabidopsis, 109 of the 149 NBS-LRR genes formed 43 clusters,26 but it was predicted that larger genomes may have a more complex distribution of CNL genes and that unclustered CNL genes are not unusual.26 Barley genes that are highly clustered, such as those on chromosome 7H, allow for higher recombination rates and faster evolution.26,86 R-genes show varying speed of evolution, with Type I genes evolving relatively faster than Type II genes.87 The expansion of CNL-C indicates that many of the CNL genes in barley are of the Type I class, suggesting a potential expansion in all grass species. Combining the evidence of duplications and clustering with Ka/Ks ratios, we see that the majority of barley CNL genes are currently undergoing purifying selection, which has been reported to be a common phenomenon among duplicated genes, especially in crop species.88 The reduction in nucleotide diversity that took place during the cultivation of barley also likely impacted evolution of R-genes.52

Current challenges in the development of durable resistance and future directions

Understanding of disease resistance has expanded greatly due to advances in molecular techniques and computational ability. Challenges regarding how efficiently we utilize genomic data to develop a more durable resistance continue to exist and can be overcome through the development and utilization of transcriptomic and metabolomics data. Additional genomic annotations are also needed as some chromosomal locations could not be accessed to determine clustering, and standardization of nomenclature is necessary. Specifically in the case of barley, current proteomic information is not complete and additional data would allow us to assess functionality. This, along with expression data upon pathogen exposure, and biochemical assays of signaling pathways are the major areas that require continued research. Also, cultivar-specific genome sequences would be useful to determine variation and educate breeders about how variation across cultivars is related to crop yield. This would allow for the development of barley cultivars that can better combat pathogens and may indirectly uncover directions for developing durable resistance in wheat and other closely related species.

Conclusions

In this study, we have presented our findings on the diversity and evolution of CNL genes in barley. The 175 identified barley R-genes show evidence of gene duplications as well as expansions and reductions of the NBS-LRR clades. The CNL gene diversity in barley is slightly higher than in rice and more than three times that in Arabidopsis. Many RPM1 homologs could be identified, indicating substantial exposure to pathogens such as P. syringae in barley’s evolutionary history. Our results also indicated that several previously identified MLA sequences are the allelic variants of two CNL genes (MLOC_66581 and MLOC_10425). Many splice variants and multiple exons per gene may have allowed rapid diversification of R-genes in barley, especially the members of the CNL-C clade. As expected, several gene clusters were found, especially in the extra-pericentromeric regions of chromosomes, a location that experiences high rate of recombination needed for rapid gene diversification. Further research should aim to measure expression levels of these genes upon pathogen exposure and assess if some of these CNL genes could be used in developing cultivars with durable resistance.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree with uncollapsed clades. See Figure 1 for detailed information including evolutionary model, coloring pattern, and outgroup.

Supplementary Figure 2. Motif structure of the 175 H. vulgare CNL genes based on MEME analysis. The CNL-A, -B, and -C clades are in blue, pink, and red, respectively. The six characteristic motifs P-loop, Kinase-2, GLPL, RNBS-B, RNBS-A, and RNBS-C are specifically named, and the following 14 motifs are named based upon their amino acid residues.

Supplementary Figure 3. Exon–intron variation across 175 CNL R-genes in barley. This illustration was generated using the program Fancygene 1.4 after input from Ensembl Genomes transcript information. Genes are presented by clade. Thick gray bars and dashed lines represent exons and introns, respectively. On the lower right corner is the summary information on the abundance of exons.

Supplementary Table 1. List of identified CNL genes and their corresponding clades.

Supplementary Table 2. Sequence information with the conserved motifs as identified by MEME analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank BV Benson and Brian Moore for their assistance in data analysis.

Footnotes

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Jike Cui, Associate Editor

PEER REVIEW: Eight peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 2,464 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

FUNDING: This study was supported by South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station, SDSU Department of Biology and Microbiology, and the USDA-NIFA Hatch Project Fund (SD00H469-13) to MPN. The authors confirm that the funder had no influence over the study design, content of the article, or selection of this journal.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Paper subject to independent expert blind peer review. All editorial decisions made by independent academic editor. Upon submission manuscript was subject to anti-plagiarism scanning. Prior to publication all authors have given signed confirmation of agreement to article publication and compliance with all applicable ethical and legal requirements, including the accuracy of author and contributor information, disclosure of competing interests and funding sources, compliance with ethical requirements relating to human and animal study participants, and compliance with any copyright requirements of third parties. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Author Contributions

Conducted data mining, data analyses, and drafted the manuscript: EJA. Conceived, designed, and supervised the research project, as well as revised the manuscript: MPN. Contributed in data analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript: SA, SN, RNR, YY. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hammond-Kosack KE, Parker JE. Deciphering plant–pathogen communication: fresh perspectives for molecular resistance breeding. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2003;14(2):177–93. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(03)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones JD, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444(7117):323–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammond-Kosack KE, Jones J. Resistance gene-dependent plant defense responses. Plant Cell. 1996;8(10):1773. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michelmore RW, Meyers BC. Clusters of resistance genes in plants evolve by divergent selection and a birth-and-death process. Genome Res. 1998;8(11):1113–30. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.11.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivas S. Nuclear dynamics during plant innate immunity. Plant Physiol. 2012;158(1):87–94. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.186163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boller T, Felix G. A renaissance of elicitors: perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern-recognition receptors. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:379–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michelmore RW, Christopoulou M, Caldwell KS. Impacts of resistance gene genetics, function, and evolution on a durable future. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2013;51:291–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam E, Kato N, Lawton M. Programmed cell death, mitochondria and the plant hypersensitive response. Nature. 2001;411(6839):848–53. doi: 10.1038/35081184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamb C, Dixon RA. The oxidative burst in plant disease resistance. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 1997;48(1):251–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hématy K, Cherk C, Somerville S. Host–pathogen warfare at the plant cell wall. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12(4):406–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolton MD. Primary metabolism and plant defense-fuel for the fire. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22(5):487–97. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-5-0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang S, Klessig DF. MAPK cascades in plant defense signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6(11):520–7. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)02103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delledonne M, Xia Y, Dixon RA, Lamb C. Nitric oxide functions as a signal in plant disease resistance. Nature. 1998;394(6693):585–8. doi: 10.1038/29087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu H. Dissection of salicylic acid-mediated defense signaling networks. Plant Signal Behav. 2009;4(8):713–7. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.8.9173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohr TJ, Mammarella ND, Hoff T, Woffenden BJ, Jelesko JG, McDowell JM. The Arabidopsis downy mildew resistance gene RPP8 is induced by pathogens and salicylic acid and is regulated by W box cis elements. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2010;23(10):1303–15. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-01-10-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shivaprasad PV, Chen H-M, Patel K, Bond DM, Santos BA, Baulcombe DC. A microRNA superfamily regulates nucleotide binding site–leucine-rich repeats and other mRNAs. Plant Cell. 2012;24(3):859–74. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.095380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flor HH. Current status of the gene-for-gene concept. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1971;9(1):275–96. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Der Biezen EA, Jones JD. Plant disease-resistance proteins and the gene-for-gene concept. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23(12):454–6. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shao F, Golstein C, Ade J, Stoutemyer M, Dixon JE, Innes RW. Cleavage of Arabidopsis PBS1 by a bacterial type III effector. Science. 2003;301(5637):1230–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1085671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Hoorn RA, Kamoun S. From guard to decoy: a new model for perception of plant pathogen effectors. Plant Cell. 2008;20(8):2009–17. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.060194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergelson J, Kreitman M, Stahl EA, Tian D. Evolutionary dynamics of plant R-genes. Science. 2001;292(5525):2281–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1061337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGrann GR, Stavrinides A, Russell J, et al. A trade off between mlo resistance to powdery mildew and increased susceptibility of barley to a newly important disease, Ramularia leaf spot. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(4):1025–37. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin X, Zhang Y, Kuang H, Chen J. Frequent loss of lineages and deficient duplications accounted for low copy number of disease resistance genes in Cucurbitaceae. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):335. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gururani MA, Venkatesh J, Upadhyaya CP, Nookaraju A, Pandey SK, Park SW. Plant disease resistance genes: current status and future directions. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;78:51–65. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers BC, Kaushik S, Nandety RS. Evolving disease resistance genes. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8(2):129–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyers BC, Kozik A, Griego A, Kuang H, Michelmore RW. Genome-wide analysis of NBS-LRR–encoding genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Online. 2003;15(4):809–34. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yue JX, Meyers BC, Chen JQ, Tian D, Yang S. Tracing the origin and evolutionary history of plant nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) genes. New Phytologist. 2012;193(4):1049–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyers BC, Dickerman AW, Michelmore RW, Sivaramakrishnan S, Sobral BW, Young ND. Plant disease resistance genes encode members of an ancient and diverse protein family within the nucleotide-binding superfamily. Plant J. 1999;20(3):317–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.t01-1-00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takken FL, Goverse A. How to build a pathogen detector: structural basis of NB-LRR function. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15(4):375–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou T, Wang Y, Chen J-Q, et al. Genome-wide identification of NBS genes in japonica rice reveals significant expansion of divergent non-TIR NBS-LRR genes. Mol Genet Genomics. 2004;271(4):402–15. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-0990-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benson BV. Disease Resistance Genes and their Evolutionary History in Six Plant Species. Biology and Microbiology, South Dakota State University; Brookings, SD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nepal MP, Benson BV. CNL disease resistance genes in soybean and their evolutionary divergence. Evol Bioinform. 2015;11:49–63. doi: 10.4137/EBO.S21782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaillon O, Aury J-M, Noel B, et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature. 2007;449(7161):463–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lozano R, Ponce O, Ramirez M, Mostajo N, Orjeda G. Genome-wide identification and mapping of NBS-encoding resistance genes in Solanum tuberosum group phureja. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmutz J, McClean PE, Mamidi S, et al. A reference genome for common bean and genome-wide analysis of dual domestications. Nat Genet. 2014;46(7):707–13. doi: 10.1038/ng.3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ameline-Torregrosa C, Wang B-B, O’Bleness MS, et al. Identification and characterization of nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat genes in the model plant Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 2008;146(1):5–21. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.104588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porter BW, Paidi M, Ming R, Alam M, Nishijima WT, Zhu YJ. Genome-wide analysis of Carica papaya reveals a small NBS resistance gene family. Mol Genet Genomics. 2009;281(6):609–26. doi: 10.1007/s00438-009-0434-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wan H, Yuan W, Bo K, Shen J, Pang X, Chen J. Genome-wide analysis of NBS-encoding disease resistance genes in Cucumis sativus and phylogenetic study of NBS-encoding genes in Cucurbitaceae crops. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Periyannan S, Moore J, Ayliffe M, et al. The gene Sr33, an ortholog of barley Mla genes, encodes resistance to wheat stem rust race Ug99. Science. 2013;341(6147):786–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1239028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saintenac C, Zhang W, Salcedo A, et al. Identification of wheat gene Sr35 that confers resistance to Ug99 stem rust race group. Science. 2013;341(6147):783–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1239022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayer KFX, Waugh R, Langridge P, et al. A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome. Nature. 2012;491(7426):711–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richter TE, Ronald PC. Plant Molecular Evolution. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2000. The Evolution of Disease Resistance Genes; pp. 195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dineley M. Animals in the Neolithic of Britain and Europe. Oxford: Oxbow Books; 2006. The Use of Spent Grain as Animal Feed in the Neolithic. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brueggeman R, Rostoks N, Kudrna D, et al. The barley stem rust-resistance gene Rpg1 is a novel disease-resistance gene with homology to receptor kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99(14):9328–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142284999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chełkowski J, Tyrka M, Sobkiewicz A. Resistance genes in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) and their identification with molecular markers. J Appl Genet. 2003;44(3):291–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hickey L, Lawson W, Platz G, et al. Mapping Rph20: a gene conferring adult plant resistance to Puccinia hordei in barley. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123(1):55–68. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1566-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hickey LT, Lawson W, Platz GJ, Dieters M, Franckowiak J. Origin of leaf rust adult plant resistance gene Rph20 in barley. Genome. 2012;55(5):396–9. doi: 10.1139/g2012-022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Büschges R, Hollricher K, Panstruga R, et al. The barley Mlo gene: a novel control element of plant pathogen resistance. Cell. 1997;88(5):695–705. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81912-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Piffanelli P, Zhou F, Casais C, et al. The barley MLO modulator of defense and cell death is responsive to biotic and abiotic stress stimuli. Plant Physiol. 2002;129(3):1076–85. doi: 10.1104/pp.010954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei F, Wing RA, Wise RP. Genome dynamics and evolution of the Mla (powdery mildew) resistance locus in barley. Plant Cell. 2002;14(8):1903–17. doi: 10.1105/tpc.002238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen Q-H, Zhou F, Bieri S, Haizel T, Shirasu K, Schulze-Lefert P. Recognition specificity and RAR1/SGT1 dependence in barley Mla disease resistance genes to the powdery mildew fungus. Plant Cell Online. 2003;15(3):732–44. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu YB. Population-based resequencing analysis of wild and cultivated barley revealed weak domestication signal of selection and bottleneck in the Rrs2 scald resistance gene region. Genome. 2012;55(2):93–104. doi: 10.1139/g11-082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nepal MP, Benson BV. CNL Disease Resistance Genes in Soybean and Their Evolutionary Divergence. Evolutionary bioinformatics online. 2015;11:49. doi: 10.4137/EBO.S21782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kersey PJ, Allen JE, Christensen M, et al. Ensembl Genomes 2013: scaling up access to genome-wide data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(D1):D546–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goodstein DM, Shu S, Howson R, et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(D1):D1178–86. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown N, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(21):2947–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finn RD, Clements J, Arndt W, et al. HMMER web server: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(W1):W30–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D222–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jones P, Binns D, Chang H-Y, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1236–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, et al. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a Mixture Model by Expectation Maximization to Discover Motifs in Bipolymers. San Diego: Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of California; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rambaldi D, Ciccarelli FD. FancyGene: dynamic visualization of gene structures and protein domain architectures on genomic loci. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(17):2281–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jupe F, Pritchard L, Etherington GJ, et al. Identification and localisation of the NB-LRR gene family within the potato genome. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(1):75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rozas J. Bioinformatics for DNA Sequence Analysis. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2009. DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis Using DnaSP; pp. 337–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andersen EJ, Shaw SR, Nepal MP. Identification of disease resistance genes in Aegilops tauschii Coss. (Poaceae) Proc South Dakota Acad Sci. 2015;94:273–87. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stevens P. Angiosperm Phylogeny Website Version 12. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, Missouri: Jul, 2012. 2001. and More or Less Continuously Updated Since. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Varshney RK, Koebner RM. Model Plants and Crop Improvement. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wolfe KH, Gouy M, Yang Y-W, Sharp PM, Li WH. Date of the monocot-dicot divergence estimated from chloroplast DNA sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86(16):6201–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bafna V, Pevzner PA. Sorting by reversals: genome rearrangements in plant organelles and evolutionary history of X chromosome. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:239–46. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leister D. Tandem and segmental gene duplication and recombination in the evolution of plant disease resistance genes. Trends Genet. 2004;20(3):116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ashfield T, Egan AN, Pfeil BE, et al. Evolution of a complex disease resistance gene cluster in diploid Phaseolus and tetraploid Glycine. Plant Physiol. 2012;159(1):336–54. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.195040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tian D, Araki H, Stahl E, Bergelson J, Kreitman M. Signature of balancing selection in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99(17):11525–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172203599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lozano R, Hamblin MT, Prochnik S, Jannink JL. Identification and distribution of the NBS-LRR gene family in the Cassava genome. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):360. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1554-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pfeil B, Schlueter J, Shoemaker R, Doyle J. Placing paleopolyploidy in relation to taxon divergence: a phylogenetic analysis in legumes using 39 gene families. Syst Biol. 2005;54(3):441–54. doi: 10.1080/10635150590945359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schmutz J, Cannon SB, Schlueter J, et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature. 2010;463(7278):178–83. doi: 10.1038/nature08670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mackey D, Holt BF, Wiig A, Dangl JL. RIN4 interacts with Pseudomonas syringae type III effector molecules and is required for RPM1-mediated resistance in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2002;108(6):743–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00661-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grant JJ, Chini A, Basu D, Loake GJ. Targeted activation tagging of the Arabidopsis NBS-LRR gene, ADR1, conveys resistance to virulent pathogens. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2003;16(8):669–80. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.8.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lorang JM, Sweat TA, Wolpert TJ. Plant disease susceptibility conferred by a “resistance” gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104(37):14861–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702572104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seeholzer S, Tsuchimatsu T, Jordan T, et al. Diversity at the Mla powdery mildew resistance locus from cultivated barley reveals sites of positive selection. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2010;23(4):497–509. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-4-0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chaw S-M, Chang C-C, Chen H-L, Li WH. Dating the monocot–dicot divergence and the origin of core eudicots using whole chloroplast genomes. J Mol Evol. 2004;58(4):424–41. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-2564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ling H-Q, Zhao S, Liu D, et al. Draft genome of the wheat A-genome progenitor Triticum urartu. Nature. 2013;496(7443):87–90. doi: 10.1038/nature11997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Goff SA, Ricke D, Lan T-H, et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica) Science. 2002;296(5565):92–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tan X, Meyers BC, Kozik A, et al. Global expression analysis of nucleotide binding site-leucine rich repeat-encoding and related genes in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7(1):56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dinesh-Kumar S, Baker BJ. Alternatively spliced N resistance gene transcripts: their possible role in tobacco mosaic virus resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97(4):1908–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.020367497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wei F, Gobelman-Werner K, Morroll SM, et al. The Mla (powdery mildew) resistance cluster is associated with three NBS-LRR gene families and suppressed recombination within a 240-kb DNA interval on chromosome 5S (1HS) of barley. Genetics. 1999;153(4):1929–48. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.4.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kuang H, Woo S-S, Meyers BC, Nevo E, Michelmore RW. Multiple genetic processes result in heterogeneous rates of evolution within the major cluster disease resistance genes in lettuce. Plant Cell. 2004;16(11):2870–94. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schlueter JA, Dixon P, Granger C, et al. Mining EST databases to resolve evolutionary events in major crop species. Genome. 2004;47(5):868–76. doi: 10.1139/g04-047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lewis JD, Wu R, Guttman DS, Desveaux D. Allele-specific virulence attenuation of the Pseudomonas syringae HopZ1a type III effector via the Arabidopsis ZAR1 resistance protein. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(4):e1000894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Henk AD, Warren RF, Innes RW. A new Ac-like transposon of Arabidopsis is associated with a deletion of the RPS5 disease resistance gene. Genetics. 1999;151(4):1581–9. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Caicedo AL, Schaal BA, Kunkel BN. Diversity and molecular evolution of the RPS2 resistance gene in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96(1):302–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Meng X, Zhang S. MAPK cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2013;51:245–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McDowell JM, Dhandaydham M, Long TA, et al. Intragenic recombination and diversifying selection contribute to the evolution of downy mildew resistance at the RPP8 locus of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1998;10(11):1861–74. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.11.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rose LE, Bittner-Eddy PD, Langley CH, Holub EB, Michelmore RW, Beynon JL. The maintenance of extreme amino acid diversity at the disease resistance gene, RPP13, in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2004;166(3):1517–27. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.3.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brooks SA, Huang L, Gill BS, Fellers JP. Analysis of 106 kb of contiguous DNA sequence from the D genome of wheat reveals high gene density and a complex arrangement of genes related to disease resistance. Genome. 2002;45(5):963–72. doi: 10.1139/g02-049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xu X, Hayashi N, Wang C-T, et al. Rice blast resistance gene Pikahei-1 (t), a member of a resistance gene cluster on chromosome 4, encodes a nucleotide-binding site and leucine-rich repeat protein. Mol Breed. 2014;34(2):691–700. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Perumalsamy S, Bharani M, Sudha M, et al. Functional marker-assisted selection for bacterial leaf blight resistance genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Plant Breed. 2010;129(4):400–6. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yoshimura S, Yamanouchi U, Katayose Y, et al. Expression of Xa1, a bacterial blight-resistance gene in rice, is induced by bacterial inoculation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95(4):1663–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Collins N, Drake J, Ayliffe M, et al. Molecular characterization of the maize Rp1-D rust resistance haplotype and its mutants. Plant Cell. 1999;11(7):1365–76. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.7.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree with uncollapsed clades. See Figure 1 for detailed information including evolutionary model, coloring pattern, and outgroup.

Supplementary Figure 2. Motif structure of the 175 H. vulgare CNL genes based on MEME analysis. The CNL-A, -B, and -C clades are in blue, pink, and red, respectively. The six characteristic motifs P-loop, Kinase-2, GLPL, RNBS-B, RNBS-A, and RNBS-C are specifically named, and the following 14 motifs are named based upon their amino acid residues.

Supplementary Figure 3. Exon–intron variation across 175 CNL R-genes in barley. This illustration was generated using the program Fancygene 1.4 after input from Ensembl Genomes transcript information. Genes are presented by clade. Thick gray bars and dashed lines represent exons and introns, respectively. On the lower right corner is the summary information on the abundance of exons.

Supplementary Table 1. List of identified CNL genes and their corresponding clades.

Supplementary Table 2. Sequence information with the conserved motifs as identified by MEME analysis.