Abstract

Background

Recurrent airway obstruction (RAO), an asthma‐like disease, is 1 of the most common allergic diseases in horses in the northern hemisphere. Hypersensitivity reactions to environmental antigens cause an allergic inflammatory response in the equine airways. Cytosine‐phosphate‐guanosine‐oligodeoxynucleotides (CpG‐ODN) are known to direct the immune system toward a Th1‐pathway, and away from the pro‐allergic Th2‐line (Th2/Th1‐shift). Gelatin nanoparticles (GNPs) are biocompatible and biodegradable immunological inert drug delivery systems that protect CpG‐ODN against nuclease degeneration. Preliminary studies on the inhalation of GNP‐bound CpG‐ODN in RAO‐affected horses have shown promising results.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical and immunological effects of GNP‐bound CpG‐ODN in a double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled, prospective, randomized clinical trial and to verify a sustained effect post‐treatment.

Animals and Methods

Twenty‐four RAO‐affected horses received 1 inhalation every 2 days for 5 consecutive administrations. Horses were examined for clinical, endoscopic, cytological, and blood biochemical variables before the inhalation regimen (I), immediately afterwards (II), and 4 weeks post‐treatment (III).

Results

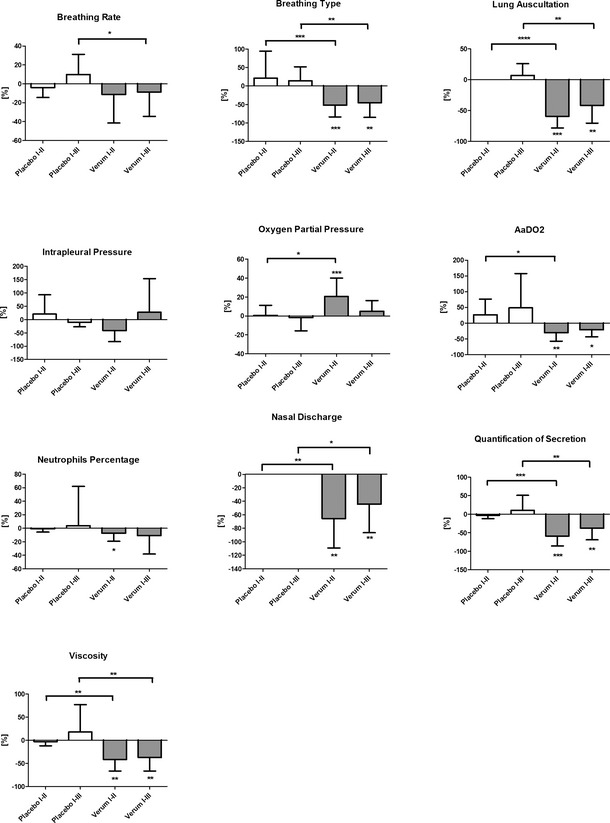

At time points I and II, administration of treatment rather than placebo corresponded to a statistically significant decrease in respiratory effort, nasal discharge, tracheal secretion, and viscosity, AaDO 2 and neutrophil percentage, and an increase in arterial oxygen pressure.

Conclusion and Clinical Importance

Administration of a GNP‐bound CpG‐ODN formulation caused a potent and persistent effect on allergic and inflammatory‐induced clinical variables in RAO‐affected horses. This treatment, therefore, provides an innovative, promising, and well‐tolerated strategy beyond conventional symptomatic long‐term therapy and could serve as a model for asthma treatment in humans.

Keywords: Gelatin nanoparticle, Immunotherapy, Inhalation, RAO

Abbreviations

- AaDO2

arterio‐alveolar oxygen pressure difference

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- bpm

breaths per minute

- CpG‐ODN

cytosine‐phosphate‐guanosine‐oligodeoxynucleotide

- GNP

gelatin nanoparticle

- HPW

highly purified water

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- PaO2

partial oxygen pressure

- RAO

recurrent airway obstruction

- RU

relative unit

- TBS

tracheobronchial secretion

- Th

T‐helper cell

- TLR‐9

toll‐like receptor 9

- Tregs

T regulatory cells

Recurrent airway obstruction (RAO) is 1 of the most common immune‐mediated allergic conditions in horses in the northern hemisphere.1, 2, 3 RAO could serve as a natural model for allergic asthma in humans and shares many characteristics with this disease.2, 4 Trigger factors are assumed to be allergens in dusty hay and moldy straw (depending on the geographical location), harmful gases (eg, ammonia, particulate matter from the environment in the stable5) infectious diseases,1 and genetic and epigenetic factors.6 The underlying pathogenesis presumably is a hypersensitivity immune reaction (types I, III, and IV) resulting in hyperreactivity of the airways to these triggers.3, 7, 8 Clinical variables include cholinergic bronchospasm, hypercrinia and dyscrinia, nasal discharge, coughing, airway neutrophilia, airway remodeling, and edema, resulting in poor performance.1, 8, 9

Cytosine‐phosphate‐guanosine‐oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG‐ODN) has been identified as a molecule that directs the immune system toward a cell‐mediated Th1 pathway, away from the pro‐allergic humoral Th2 line response, described as a Th2/Th1‐shift.3, 10, 11 Unmethylated CpG‐ODN molecules exist naturally in prokaryotic viral and bacterial DNA and stimulate the mammalian immune system, via the Th1 pathway, against infectious agents.10, 11 A recognition receptor for CpG‐ODN is the toll‐like‐receptor‐9 (TLR‐9) which has been identified in macrophages, bronchial epithelial cells, capillary endothelial cells, and neutrophil granulocytes in equine lungs.12 Drug delivery systems such as lipid13 or gelatin nanoparticles (GNPs) have been used to protect CpG‐ODN in vivo against nuclease degeneration.14, 15 GNPs represents a highly efficient drug delivery system, which also has the advantages of being aerodynamically stable after inhalation, immunologically inert, biodegradable, and biocompatible.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

As an adjuvant, CpG‐ODN has been successfully used both in a human phase I and IIa in vivo asthma study with the house dust mite allergen as well as in a study of atopic dogs with specific allergens as an allergen‐specific immunotherapy.20, 21 CpG‐ODN also has been applied as an adjuvant in in vitro and in vivo vaccination studies.22, 23, 24, 25 Furthermore, it has been used as an adjuvant in an equine influenza vaccine in horses23 and in combination with a Rhodococcus equi vaccine.22

A preliminary study of the inhalation of GNP‐bound CpG‐ODN as the only active agent showed promising clinical results in a small group of RAO‐affected horses and healthy horses, in contrast to previously used adjuvants.26 No local or systemic inflammatory reactions were observed.26 The efficiency of this novel formulation was demonstrated by improvement in arterial blood gases, breathing rate, amount of intratracheal mucus accumulation, viscosity, and airway neutrophilia in RAO‐affected horses.26

The goal of this exploratory study was (i) to verify the results of the previous pilot study using a larger subject group and with a placebo control, and (ii) to investigate a possible sustained response in the weeks after treatment in the field. The main goals of the field study were the evaluation of (i) a clinically relevant improvement in breathing pattern, respiratory rate, arterial blood gases, and AaDO2, as well as (ii) a clinically relevant percentage decrease in neutrophilic granulocytes in the airways, as well as decrease in intrapleural pressure, nasal discharge, amount of secretion, and viscosity of secretions in the airways in comparison to the initial examination and the control group after 5 inhalations of nanoparticle‐bound CpG‐ODN. Additionally, the duration of the effectiveness of the nanoparticle immunotherapy, as well as the tolerability of the formulation and the absence of adverse effects, were examined.

The first hypothesis of this study was that placebo administration would show no or very limited improvement in the monitored variables in comparison to the experimental administration. The secondary hypothesis was that the nanoparticle‐bound CpG‐ODN immunotherapy would produce no local or systemic adverse reactions.

Methods

Study Design

This study was performed as a randomized, double‐blinded, and placebo‐controlled clinical trial. The subjects were 24 horses with a history of chronic RAO (mean age, 16.1 years ± 5.1; 5 mares, 17 geldings, and 2 stallions; mean weight, 519.4 kg ± 129.7). The following inclusion criteria were applied: increased respiratory rate at rest (>16/min), increased abdominal breathing(“heaves”), abnormal auscultatory findings at rest, increased numbers of neutrophils in the airways (>25%), decreased partial pressure of arterial oxygen (<90 mmHg), increased intrapleural pressure (>15 cmH2O), and clinical signs induced by contact with straw and hay, as well as reversibility of clinical signs with avoidance of allergens and sustained time on pasture1, 27. All of the horses were kept in their usual environment during the entire study (April through July) and were examined without modifying their stabling (open bar stall, n = 7; box with sawdust, n = 10; straw, n = 7), feeding (dry hay, n = 21; soaked hay, n = 3) or activity. For at least 2 months before and during the study, the horses received neither supplement medication nor improvements to their stabling or management. This trial was performed as an exploratory field study. In the placebo group, 25% of the horses were kept in open stables and 75% in box stalls (bedding material was shavings and sawdust in 38% and straw in 38%). All of the horses in the placebo group were fed dry hay before and during the study. In the active treatment group, 31% of the horses were kept in open stables and 69% in stalls. In 81% of the cases, the horses were fed dry hay and 19% were fed wet hay (only 3 of the horses kept in stalls received wet hay).

Two different investigators performed the inhalation therapy (BL) and clinical examinations (JK). In addition, the placebo and experimental formulations could not be differentiated visually. Neither the horse owners nor the examiners knew if the horse had received the placebo or active treatment.

The patients were randomly assigned to 2 groups. After 8 horses were selected for the placebo group, the remaining horses were assigned to the experimental treatment group. This randomization took place after all of the patients were selected for the study. The placebo group (n = 8) received inhalations with highly purified water (HPW) and GNP, and the experimental treatment group (n = 16) received inhalations with GNP‐bound CpG‐ODN.1 , 26 The inhalation regimen, corresponding to the procedure in the previous study, was performed with the Equine Haler2 and the AeroNeb Go mesh vibrator.3 , 26 In total, each horse received 5 inhalations, each separated by 2 days. The horses were examined 3 times: at the beginning, ie, before the first administration of experimental treatment or placebo; (I) to determine each horsis clinical status; directly after the final inhalation (II); and 4 weeks after the final inhalation (III), to provide insight on the duration of effectiveness. To this end, each examination included clinical examinations, endoscopy, cytology, and serum biochemistry, as well as measurement of intrapleural pressure.

The nanoparticles were produced and charged with CpG‐ODN according to the protocol of a previous study26. The study was approved by the regional legal agency for animal testing of the State Government of Bavaria, Germany (No. 55.2‐1‐54‐2531‐31‐10).

Clinical Examination and Scoring

The clinical variables were evaluated according to established and standardized scoring systems when possible. The following variables were examined: breathing rate per minute (bpm), breathing type (relative units [RU] in the range of 0–3, where 0 = no or little movement in the ventral flank and 3 = obvious abdominal lift and heave line),28 nasal discharge (RU in the range of 0–2, where 0 = none, 1 = mild and 2 = moderate discharge), auscultation of the lungs and trachea (in the range of RU 0 to 4, where 0 = physiological, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, 4 = wheeze or rhonchus),1, 26, 27 and arterial blood gas parameters.29 The latter consisted of partial oxygen pressure (paO2), with a normal reference value of 100 ± 5 mmHg, and carbon dioxide pressure (paCO2), with a normal reference value of 40 ± 5 mmHg). Arterial blood gases were measured by an IRMA blood analysis system.4 The arterio‐alveolar‐oxygen‐pressure difference (AaDO2) was calculated from the actual air pressure and measured arterial blood gases (AaDO2 = [actual air pressure − 47 mmHg] × 0.2095 − PaCO2 − PaO2).29 In addition, an endoscopic examination and a quantification of secretion (grade 0–5, where 0 = none, clean, singular tracheobronchial secretion [TBS] to 5 = extreme, profuse amounts)30 and viscosity (where grade 1 = fluid to 5 = viscous)30 of the TBS was performed. Cytological examinations of the TBS samples were performed to determine the percentage of neutrophils in the total cell count after staining with Diff‐Quick solution.5 Indirect measurement of the maximum intrapleural pressure differences (Δ Ppl max) was performed by a Venti‐Graph6 via esophageal probe.31

To test the tolerability of the formulation and its application, the horses were regularly monitored for the signs of increased nasal discharge, coughing, bronchospasm, increased respiratory rate, endoscopically visible local hyperemia of the mucous membranes, follicular hyperplasia, and decreased partial oxygen pressure. Furthermore, body temperature, differential blood cell count, and plasma fibrinogen concentration were measured to evaluate the systemic effects of treatment.

Statistical Analysis

The comparison of patients within each group (placebo and experimental treatment) for the preliminary examination before treatment was carried out for normally distributed data (based on Shapiro‐Wilk analysis) with the paired Student's t‐test for parametric data. For non‐parametric data, the Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test was used for paired values (comparison within the groups) and the Mann‐Whitney test was used for unpaired data (comparison between the groups). All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software.7 Results with a calculated value of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (displayed as *; P < 0.01 as **; P < 0.001 as ***) and were reported as the mean ± S.D. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated and presented in brackets. Effect size (Cohen's d) was assessed for each piece of data (to estimate clinical relevance: mild, d = 0.2–0.3; moderate, d = 0.5; large, d > 0.8). The calculation of the effect size was performed using the EffectSize Calculator.8 ,29

Results

Safety

Throughout the whole study period, no local or systemic inflammatory reactions or adverse effects were observed after inhalation treatment with GNP‐bound CpG‐ODN. Specifically, no clinically detectable increased nasal discharge, coughing, bronchospasm, increased breathing rate, endoscopically visible local hyperemia, follicular hyperplasia, or decreased arterial blood gas pressure were observed. In addition, no increase in rectal temperature, peripheral blood absolute and differential leukocyte counts or plasma fibrinogen concentrations were detected.

Respiratory Rate

No clinically or statistically significant decrease in respiratory rate was observed, either directly after placebo inhalation or after 4 weeks (Table 1, Fig 1). After treatment, no statistically significant improvement (P = 0.0856; clinical relevance, d = 0.6; CI:−0.1 to 1.3) could be detected immediately after treatment (Table 1, Fig 1) or after 4 weeks (clinical relevance, d = 0.3; CI: −0.4 to 1.0). However, a statistically significant difference (P = 0.0247) in the percentage decrease in respiratory rate was detected between the placebo and treatment groups between the first and last examination (I–III) (Fig 1).

Table 1.

Clinical, endoscopic, cytological, and biochemical parameters: Results of breathing rate and type, lung auscultation, intrapleural pressure measurement, oxygen partial pressure, AaDO2, neutrophil percentage of TBS, nasal discharge, endoscopic quantification of secretion and viscosity depicted before (I), after 5 inhalations (II), and 4 weeks post‐treatment (III) with placebo (n = 8 RAO‐affected horses) versus treatment administration (n = 16 RAO‐affected horses) (RU = relative units, scoring system; mean ± SD)

| Breathing rate [1/min] | Breathing type [RU] | Auscultation [RU] | Interpleural pressure [cmH20] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | I | II | III | I | II | III | I | II | III | |

| Placebo (n = 8) | 21.0 ± 5.1 | 20.0 ± 4.7 | 23.1 ± 10.1 | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 26.8 ± 29.4 | 25.5 ± 19.8 | 28.0 ± 36.4 |

| Verum (n = 16) | 21.6 ± 5.7 | 18.3 ± 4.6 | 19.5 ± 6.6 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 26.7 ± 22.5 | 9.8 ± 8.5 | 30.8 ± 33.6 |

| Oxygen partial pressure [mmHg] | AaDO2 [mmHg] | Neutrophils [%] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | I | II | III | I | II | III | |

| Placebo (n = 8) | 79.6 ± 11.1 | 76.1 ± 8.0 | 77.9 ± 13.6 | 23.6 ± 12.6 | 27.0 ± 7.2 | 26.5 ± 11.6 | 68.0 ± 18.7 | 67.4 ± 19.6 | 73.2 ± 12.3 |

| Verum (n = 16) | 71.4 ± 15.9 | 85.9 ± 13.1 | 75.1 ± 17.1 | 30.6 ± 11.5 | 19.2 ± 11.8 | 25.7 ± 13.6 | 78.9 ± 17.7 | 72.9 ± 18.1 | 70.2 ± 24.4 |

| Nasal discharge [RU] | Quantification of secretion [RU] | Viscosity [RU] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | I | II | III | I | II | III | |

| Placebo (n = 8) | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 0.8 |

| Verum (n = 16) | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 0.8 |

Figure 1.

Relative reduction or increase of clinical, endoscopic, cytological, and biochemical parameters: Relative decrease or increase of breathing rate and pattern (calculated value of P < 0.05 displayed as *; P < 0.01 as **; P < 0.001 as ***; P < 0.0001 as ****), lung auscultation, intrapleural pressure measurement, oxygen partial pressure, AaDO 2, percentage of neutrophils in TBS, nasal discharge, endoscopic quantification of secretion and viscosity depicted in percent between first and second (I–II) and first and third (I–III) examinations and in comparison between placebo (white bars, n = 8 RAO‐affected horses) and treatment group (gray bars, n = 16 RAO‐affected horses; mean ± SD).

Breathing Pattern

The placebo group showed no statistically significant improvement in breathing pattern after the inhalation regimen (Table 1, Fig 1). However, a statistically significant (P = 0.0007; d = 1.6; CI: 0.8–2.4) improvement in breathing type was detected in the treatment group after 5 inhalations (Table 1, Fig 1), and a reduction of one grade from the initial status was observed after 4 weeks (P = 0.005; clinical relevance, d = 1.3; CI: 0.5–2.1) (Table 1, Fig 1). A statistically significant difference was detected between the placebo and experimental treatment groups in percentage decrease in breathing pattern between the first and second examination (I–II; P = 0.0008) as well as between the first and third examination (I–III, P = 0.0051; Fig 1).

Lung Auscultation

No statistically significant improvement in auscultation was observed after the inhalation regimen in the placebo group (Table 1, Fig 1). By contrast, a significant (P = 0.0004; clinical relevance, d = 1.9; CI: 1.0–2.6) improvement in auscultation was detected in the treatment group after 5 inhalations. In the treatment group, a mean decrease of >1.5 grades was observed. A significant decrease in duration of efficacy (P = 0.0018; clinical relevance, d = 1.4; CI: 0.6–2.2) also was observed in horses treated with GNP‐bound CpG after 4 weeks (Table 1, Fig 1). A statistically significant difference was observed between the placebo and treatment groups when comparing percentage improvement in auscultation between the first and second examination (I–II; P < 0.0001) and between the first and third examination (I–III; P = 0.0015; Fig 1).

Intrapleural Pressure

No statistically significant decrease in intrapleural pressure after inhalation treatment was observed in the placebo group (Table 1, Fig 1). The treatment group showed an average improvement in intrapleural pressure of 16 cmH2O (clinical relevance, d = 1.0; CI: 0.2–1.7) immediately after inhalation administration, but this difference lacked statistical significance (P = 0.1269; Table 1, Fig 1) because of large individual variations. The clinical effect observed did not persist 4 weeks after treatment. No statistically significant differences between placebo and treatment group were observed when comparing percentage intrapleural pressure improvement (Fig 1).

Partial Oxygen Pressure (pO2)

The placebo group failed to show any statistically significant improvement in arterial blood gas results post inhalation (Table 1, Fig 1). However, pO2 increased on average by approximately 14 mmHg in the treatment group (from 71.4 mmHg ± 15.9 to 85.9 mmHg ± 13.1) after 5 inhalations (P = 0.0006; clinical relevance, d = 1.0; CI: 0.2–1.7) (Table 1). A persistent effect over 4 weeks was not observed in the treatment group (P = 0.1523). A statistically significant difference was observed between the placebo and treatment groups when comparing the percentage increase of partial oxygen pressure between the first and the second examination (I–II; P = 0.0228; Fig 1).

Arterio‐alveolar Oxygen Pressure Difference (AaDO2)

The placebo group showed an increase in AaDO2 after inhalation of HPW and GNP (Table 1, Fig 1). By contrast, a decrease of 11 mmHg of AaDO2 (P = 0.0021; clinical relevance, d = 1.0; CI: 0.2–1.7) was observed in the treatment group immediately after the inhalation regime, with a statistically significant persistent effect 4 weeks post‐treatment (P = 0.022, clinical relevance, d = 0.4; CI: −0.3 to 1.1; Table 1, Fig 1). A statistically significant difference also was detected between the placebo and treatment groups when comparing the percentage decrease of AaDO2 between the first and the second examinations (I–II; P = 0.0174; Fig 1).

Neutrophil Percentage

A statistically significant decrease in the neutrophil percentage in TBS was not observed in the placebo group (Table 1, Fig 1). After 4 weeks without treatment, a mild increase in neutrophil percentage then was detected in the placebo group (Table 1, Fig 1). However, in the treatment group, a statistically significant decrease (P = 0.015, clinical relevance, d = 0.3; CI: −0.4 to 1.0) was observed after 5 inhalations (from 78.9 ± 17.7% to 72.9 ± 18.1%). Four weeks post‐treatment, no statistically significant effect (P = 0.0975, clinical relevance, d = 0.4; CI: −0.3 to 1.1) was observed (to 70.2 ± 24.4%) because of greater SD (Table 1, Fig 1). No statistically significant difference between the placebo and treatment groups comparing the decrease of neutrophil percentage was observed (I–II examination, P = 0.1670; I–III examination, P = 0.0897; Fig 1).

Nasal Discharge

The placebo group showed no statistically significant improvement in nasal discharge after the inhalation regimen with HPW and GNP (Table 1, Fig 1). By contrast, within the treatment group, a statistically significant decrease (P = 0.0012; clinical relevance, d = 1.5; CI: 0.7–2.2) after 5 inhalations was observed (Table 1, Fig 1). This effect persisted four weeks post‐treatment (P = 0.0048; clinical relevance, d = 1.3; CI: 0.5–2.0; Table 1, Fig 1). A statistically significant difference was detected between the placebo and experimental treatment groups comparing the percentage decrease in nasal discharge between the first and second examinations (I–II; P = 0.0013) as well as between the first and third examinations (I–III; P = 0.0135; Fig 1).

Quantity of Secretion

After the inhalation regimen with placebo, no statistically significant decrease in the amount of mucus was observed on tracheal endoscopy (Table 1, Fig 1). By contrast, a statistically significant decrease (P = 0.0007; clinical relevance, d = 1.7; CI: 0.9–2.5) of 1.9 RU in secretion amount was observed in the horses treated with the experimental treatment (Table 1). A persistent effect 4 weeks post‐treatment was detected in the treatment group with a decrease of 1.5 RU after 4 weeks (P = 0.0036; clinical relevance, d = 1.5; CI: 0.6–2.2; Table 1, Fig 1). A statistically significant difference was detected between placebo and treatment groups when comparing the percent decrease in quantity of secretion between the first and the second examinations (I–II; P = 0.0003) as well as between the first and the third examinations (I–III; P = 0.0038; Fig 1).

Viscosity of Secretion

No statistically significant decrease in viscosity of the TBS was observed in the placebo group (Table 1, Fig 1). However, the treatment group showed a statistically significant decrease in TBS viscosity of 1.4 RU (P = 0.0014; clinical relevance, d = 1.3; CI: 0.5–2.1) after the inhalation regimen (Table 1, Fig 1). A statistically significant persistent effect was detected in the treatment group (P = 0.0029; clinical relevance, d = 1.2; CI: 0.4–1.9; Table 1, Fig 1). A statistically significant difference was detected between the placebo and treatment groups when comparing percentage decrease in secretion viscosity between the first and the second examinations (I–II; P = 0.0014) as well as between the first and the third examinations (I–III; P = 0.0065; Fig 1).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first attempt at nanoparticle‐based inhalation immunotherapy for horses. Clinical examination, endoscopy, cytology and biochemical variables were evaluated before treatment to determine the pre‐treatment health status of each horse, as well as immediately after 5 inhalations (10 days after the primary examination), and 4 weeks after the last treatment to determine the duration of efficacy. For at least 2 months before and during the course of the field study, the horses received no supplement medication or any modifications to their stabling or management. The patients were treated under their normal stabling conditions and individual exposure to allergens.

The method of inhalation was chosen as a local, topical administration of immunotherapy for the lungs, and proved to be both practical and appropriate. The inhalation system used (ie, a combination of “Equine Haler” and “Aeroneb go”) was already proven in a previous study26 to be a practical, simple and well‐tolerated system. Its respiratory droplet size,19 quiet nebulization,26 and short inhalation time26 proved to be well adapted for use.

Gelatin nanoparticles have been proven to be immunologically inert, aerodynamically stable, biodegradable, and well tolerated drug delivery systems. Their particular relevance lies in their stabilization and protection of the chimeric backbone26 of the Class A CpG‐ODN by steric shielding, as opposed to DNase;15 in their selective targeting of the TLR‐9 positive target cells; and in the resulting increased effectiveness of the CpG‐ODN.15, 32 These aspects, as well as the fact that GNPs are used in (potentially) food‐producing animals, render these nanoparticles of a great importance for a potential application in humans with allergic asthma. The inhalation regimen, with each inhalation session given every 2 days, was selected because of the known maximum 48‐hour in vivo stability of the ODN.33

Within the framework of the study design, the placebo group was intentionally restricted to 8 horses. This decision was made based on ethical considerations regarding the animals’ well‐being, the expected efficacy of treatment and the added value of information, as well as the decrease of animal suffering because of the severity of the disease. Because of the smaller number of horses in the placebo group, one cannot expect exactly identical output values, because of the random distribution of data. The effect size (Cohen's d, d > 0.8 for high clinical relevance) and the 95% CI were calculated in addition to the significance levels, in order to better assess the clinical relevance of the results presented in this study.34

To ensure a safe application of the formulation, possible local and systemic inflammatory reactions or adverse effects were documented, with the help of a modified scoring system from the Veterinary Co‐operative oncology Group's Common Criteria of Adverse Events (VCOG‐CTCAE) V1.0.35 In accordance with a previous study, no signs of local or systemic inflammatory reactions (including the measurement of plasma fibrinogen concentrations and a differential blood count) or any other adverse effects were observed from the GNP‐bound CpG inhalation treatment. Thus, the second goal of this field study (verification of treatment safety) could be completely satisfied.

As it has already been shown in vitro using equine BAL cells and in vivo, GNP‐bound CpG treatment stimulates upregulation of IL‐10.26, 32, 35 This cytokine, which among others is formed from Treg cells, has a regulatory effect on excessive pro‐inflammatory Th1 and pro‐allergic Th2 immune responses, as they occur in the lungs of RAO horses to various degrees.8 The anti‐inflammatory and anti‐allergic effect of this immunotherapy, through the activation of TLR‐9 receptors in the lungs, will, according to our hypothesis, stimulate Treg cells to regulate and restore the Th1/Th2 balance that is disturbed in RAO.

The most important effect of the nanoparticle inhalation immunotherapy was the decrease in secretion quantity (ie, nasal discharge and endoscopic findings) as well as the auscultation findings, breathing type and the supply of oxygen to the lungs. Not only was a significant improvement shown in all of these variables after 5 inhalations but also a sustained effect was documented after 4 weeks without supplement treatment or modifications to management conditions. This finding must be particularly emphasized, because the horses in the study were not held in optimal conditions and had constant contact with hay. The clinical relevance of the specific effects also could be classified as very high (d > 0.8).

Whether the immunotherapy has a particularly pronounced effect on the mucus‐producing goblet cells can only be surmised from these results. In mouse models, it is clear that Th2‐mediated immunopathogenesis can be modulated and positively influenced by use of immunostimulatory DNA.11, 15 The neutrophils, however, showed a comparatively small decrease, which among other things could be explained by sustained exposure to allergens. Through repeated inhalations (ie, booster doses), as was already indicated in our previous pilot study,26, 35 and perhaps through a modified dosage (ie, dose‐response study), this effect potentially could be strengthened. The previous study also showed an average 30% increase in reduction of neutrophil granulocytes after 5 inhalations26, 35 during the winter treatment, during which management conditions were optimized.

The improvement of partial oxygen pressure at rest, as well as intrapleural pressure, indicates improved ventilation in the lungs. This also was reflected in the considerably improved breathing pattern and the decrease in active respiratory effort. The cause is most likely the decrease in secretion, as well as a decrease in cholinergic bronchospasm.

In other studies in which CpGs were deployed, for example in a study on asthma in humans,20 and a study on dogs with atopic dermatitis,21 CpGs were used as adjuvants for an allergen‐specific immunotherapy or as vaccine adjuvants for increased effectiveness of the human hepatitis B11 and the equine influenza and Rhodococcus equi vaccines.22, 23, 24, 25 In these studies, the CpGs induced a strong Th1 cell‐mediated and humoral immune response.11 However, they have never been deployed previously as an immuno‐modulatory monotherapy, by inhalation or bound to nanoparticles. As such, this study represents the first inhalation nanoparticle immunotherapy of its kind and is a novel treatment concept for horses. Its use in allergic asthma in humans could therefore also be considered.

The advantage of this immunotherapy lies in stimulation independent of allergens, as opposed to classic hyposensitization. Furthermore, this therapeutic concept works at the immunologic level and helps stabilize the Th1/Th2 balance, which can be of clinical relevance for other allergic and inflammatory diseases. This therapeutic concept opens new possibilities beyond the usual purely symptomatic treatment concepts with cortisone and bronchodilators, or the often unfeasible avoidance of allergen contact. All of the patients included in this study were kept and examined in their normal management conditions, without modifying the usual bedding, feed (hay), or the use of the horse. The goal was to test the effectiveness of the inhalative CpG treatment under individual natural environmental conditions.

The relatively small number of inhalations and the persistent effect over at least a month must be emphasized. Altogether, a significant improvement was observed in the treatment group after 5 inhalations, with a persistent effect over 4 weeks in 70% of the clinical, endoscopic and cytological variables. Thus, an important goal of the study, the verification of the clinical efficacy of the concept (Phase IIa), was fulfilled. Upon review of the examinations, the placebo application, as expected, showed no improvement whatsoever in the variables tested.

Few inhalation treatments have produced a substantial and sustained improvement of allergic and inflammatory clinical, endoscopic, cytological, and biochemical variables. The results of the present field study completely satisfied the questions posed and furthermore indicated a persistent effect in many of the variables tested. This therapeutic approach introduces new perspectives beyond symptomatic treatment methods, and therefore can serve as a model for asthma therapy in humans.

Acknowledgments

A part of the statistical appraisal for the regional legal agency for animal testing was performed by Dr. Tibor Schuster of the Institute of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology, Klinikum Rechts der Isar, Technical University of Munich (Germany). The authors thank Ms. Katharine Barske, Ms. Elena Serkin and Prof. Dr. Lutz S. Goehring for critical revision of the paper.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: Authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Off‐label Antimicrobial Declaration: Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

Funding: Parts of the research were supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (Germany) (GE’2044/4‐1). The AeroNeb Go vibrating mesh nebulizer (Aerogen, Galway, Ireland) was kindly sponsored by Inspiration Medical (Bochum, Germany).

The study was conducted at the Equine Clinic, Centre for Clinical Veterinary Medicine, LMU Munich, Germany. Abstracts of this study were presented in part at the 2013 European College of Equine Internal Medicine (ECEIM) Congress in Le Touque, France, the 2013 5th World Equine Airways Symposium (WEAS) in Calgary, Canada and the 2014 European Academy of Allergy Asthma and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) Congress in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Footnotes

Biomers GmbH, Ulm, Germany

Equine HealthCare Aps, Hoersholm, Denmark

Aerogen, Galway, Ireland

Diametrics Medical incorporated, Keller Medical, Bad Soden, Germany

Medion diagnostics, Düdingen, Switzerland

Boehringer Ingelheim, Germany

GraphPad software Inc., La Jolla

http://davidmlane.com/hyperstat/effect_size.htm, Robert Coe

References

- 1. Robinson NE. Recurrent airway obstruction (Heaves) In: Lekeux P, ed. Equine Respiratory Diseases. Ithaca, New York: International Veterinary Information Service; 2001. [http://www.ivis.org/special_books/Lekeux/ robinson/chapter_frm.asp?LA=1] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neuhaus S, Bruendler P, Frey CF, et al. Increased parasite resistance and recurrent airway obstruction in horses of a high‐prevalence family. J Vet Intern Med 2010;24:407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lunn P, Horohov D. The equine immune system In: Reed SM, Bayly WM, Sellon DC, eds. Equine Internal Medicine, 3rd ed St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:2–56. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kirschvink N, Reinhold P. Use of alternative animals as asthma models. Curr Drug Targets 2008;9:470–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Millerick‐May ML, Karmaus W, Derksen FJ, et al. Particle mapping in stables at an American Thoroughbred racetrack. Equine Vet J 2011;43:599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gerber V, Baleri D, Klukowska‐Rötzler J, et al. Mixed inheritance of equine recurrent airway obstruction. J Vet Intern Med 2009;23:626–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Künzle F, Gerber V, Van Der Haegen A, et al. IgE‐bearing cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and allergen‐specific IgE levels in sera from RAO‐affected horses. J Vet Med A 2007;54:40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ainsworth DM, Cheetham J. Disorders of the respiratory system In: Reed SM, Bayly WM, Sellon DC, eds. Equine Internal Medicine, 3rd ed St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:340–344. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moran G, Folch H. Recurrent airway obstruction in horses—An allergic inflammation: A review. Vet Med ‐ Czech 2011;56:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fonseca D, Kline J. Use of CpG oligonucleotides in treatment of RAO and allergic disease. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2009;61:256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vollmer J, Krieg AM. Immunotherapeutic applications of CpG oligodeoxynucleotide TLR9 agonists. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2009;61:195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schneberger D, Caldwell S, Singh Suri S, et al. Expression of toll‐like receptor 9 in horse lungs. Anat Rec 2009;292:1068–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilson KD, de Jong SD, Tam YK. Lipid‐based delivery of CpG oligonucleotides enhances immunotherapeutic efficacy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2009;61:233–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bourquin C, Anz D, Zwiorek K, et al. Targeting CpG oligodeoxynucleotides to the lymph node by nanoparticles elicits efficient antitumoral immunity. J Immunol 2008;181:2990–2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zwiorek K, Bourquin C, Battiany J, et al. Delivery by cationic gelatin nanoparticles strongly increases the immunostimulatory effects of CpG oligonucleotides. Pharm Res 2008;25:551–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brzoska M, Langer K, Coester C, et al. Incorporation of biodegradable nanoparticles into human airway epithelium cells‐in vitro study of the suitability as a vehicle for drug or gene delivery in pulmonary diseases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;318:562–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tseng C‐L, Yueh‐Hsiu WuS, Wang W‐H, et al. Targeting efficiency and biodistribution of biotinylated‐EGF‐conjugated gelatine nanoparticles administered via aerosol delivery in nude mice with lung cancer. Biomaterials 2008;29:3014–3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tseng C‐L, Su W‐Y, Yen K‐C, et al. The use of biotinylated‐EGF‐modified gelatine nanoparticle carrier to enhance cisplatin accumulation in cancerous lungs via inhalation. Biomaterials 2009;30:3476–3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fuchs S, Klier J, May A, et al. Towards an inhalative in vivo application of immunomodulating gelatin nanoparticles in horse‐related preformulation studies. J Microencapsul 2012;29:615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Senti G, Johansen P, Haug S, et al. Use of A‐type CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as an adjuvant in allergen‐specific immunotherapy in humans: A phase I/IIa clinical trial. Clin Exp Allergy 2009;39:562–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mueller RS, Veir J, Fieseler KV, Dow SW. Use of immunostimulatory liposome‐nucleic acid complexes in allergen‐specific immunotherapy of dogs with refractory atopic dermatitis—A pilot study. Vet Dermatol 2005;16:61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hullmann AG. Prophylaxe der Rhodococcus equi‐Pneumonie bei Fohlen durch Vakzination mit Rhodococcus equi‐Impfstoff und Adjuvans CpG XXXX. School of Veterinary Medicine Hannover; 2006. Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lopez AM, Hecker R, Mutwiri G, et al. Formulation with CpG ODN enhances antibody responses to an equine influenza virus vaccine. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2006;114:103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu T, Nerren J, Murrell J, et al. CpG‐induced stimulation of cytokine expression by peripheral blood mononuclear cells of foals and their dams. J Jevs 2008;28:419–426. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu T, Nerren J, Liu M, et al. Basal and stimulus‐induced cytokine expression is selectively impaired in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of newborn foals. Vaccine 2009;27:674–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klier J, Fuchs S, May A, et al. A nebulized gelatin nanoparticle‐based CpG formulation is effective in immunotherapy of allergic horses. Pharm Res 2012;29:1650–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Robinson NE. International workshop on equine chronic airway disease. Michigan State University. Equine Vet J 2001;33:5–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gerber V, King M, Schneider DA, Robinson NE. Tracheobronchial mucus viscoelasticity during environmental challenge in horses with recurrent airway obstruction. Equine Vet J 2000;32:411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grabner A. Arterielle Blutgasanalyse In: Kraft W, Dürr UM, eds. Klinische Labordiagnostik in der Tiermedizin, 6th ed Stuttgart: Schattauer; 2005:429–430. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gerber V, Straub R, Marti E, et al. Endoscopic scoring of mucus quantity and quality: Observer and horse variance and relationship to inflammation, mucus viscoelasticity and volume. Equine Vet J 2004;36:576–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Deegen E, Klein HJ. Interpleuraldruckmessungen und Bronchospasmolysetests mit einem portalen Ösophagusdruckmessgerät. Pferdeheilkunde 1987;21:213–221. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Klier J, May A, Fuchs S, et al. Immunostimulation of bronchoalveolar lavage cells from recurrent airway obstruction‐affected horses by different CpG‐classes bound to gelatin nanoparticles. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2011;144:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mutwiri GK, Nichani AK, Babiuk S, et al. Strategies for enhancing the immunostimulatory effects of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Control Release 2004;97:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakagawa S, Cuthill I.C. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: A practical guide for biologist. Biol Rev 2007;82:591–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klier J. Neuer Therapieansatz zur Behandlung der COB des Pferdes durch Immunstimulation von BAL‐Zellen mit verschiedenen CpG‐Klassen. Munich: School of Veterinary Medicine, Ludwig‐Maximilians University; 2011. Thesis. [Google Scholar]