Abstract

Background

Cystinuria is an inherited metabolic disease that is relatively common in dogs, but rare in cats and is characterized by defective amino acid reabsorption, leading to cystine urolithiasis.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to report on a mutation in a cystinuric cat.

Animals

A male domestic shorthair (DSH) cat with cystine calculi, 11 control cats from Wyoming, and 54 DSH and purebred control cats from elsewhere in the United States.

Methods

Exons of the SLC3A1 gene were sequenced from genomic DNA of the cystinuric cat and a healthy cat. Genetic screening for the discovered polymorphisms was conducted on all cats.

Results

A DSH cat showed stranguria beginning at 2 months of age, and cystine calculi were removed at 4 months of age. The cat was euthanized at 6 months of age because of neurological signs possibly related to arginine deficiency. Twenty‐five SLC3A1 polymorphisms were observed in the sequenced cats when compared to the feline reference sequence. The cystinuric cat was homozygous for 5 exonic and 8 noncoding SLC3A1 polymorphisms, and 1 of them was a unique missense mutation (c.1342C>T). This mutation results in a deleterious amino acid substitution (p.Arg448Trp) of a highly conserved arginine residue in the rBAT protein encoded by the SLC3A1 gene. This mutation was found previously in cystinuric human patients, but was not seen in any other tested cats.

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

This study is the first report of an SLC3A1 mutation causing cystinuria in a cat, and could be used to characterize other cystinuric cats at the molecular level.

Keywords: Hereditary disease, Metabolic disease, Nephropathy, Urolithiasis

Abbreviations

- Arg, R

arginine

- bp

base pair

- COLA

cystine, ornithine, lysine and arginine

- DLH

domestic longhair

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- DSH

domestic shorthair

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- Gln, Q

glutamine

- Ile, I

isoleucine

- Met, M

methionine

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RFLP

restriction fragment length polymorphism

- SIFT

sorting intolerant from tolerant

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- TIM

triosephosphate isomerase

- Trp, W

tryptophan

- Val, V

valine

Cystinuria is a hereditary renal transport disorder involving cystine and the dibasic amino acids ornithine, lysine, and arginine, collectively known as COLA.1, 2 This inborn error of metabolism leads to the formation of cystine crystals and uroliths in the urinary tract, which can result clinically in stranguria, hematuria, urinary obstruction, and renal failure. Cystinuria has been reported in humans (OMIM #220100)1 and animals including dogs (OMIA 000256‐9615),2, 3 cats (OMIA 001878‐9685),4, 5 ferrets,6 mice,7 and some wild carnivores including maned wolves,8 caracals,9 and servals (U.G. Giger, unpublished).10

Feline cystinuria was first documented in 1991.4 Osborne et al. summarized the clinical features in 18 cystinuric domestic shorthair (DSH) and purebred cats.5 Cystinuria in cats occurs less commonly than in dogs based upon laboratory urolithiasis surveys. Cystine calculi represent only 0.1% of all uroliths seen in nonpurebred and purebred cats in the United States and Canada compared with 0.3–1% of canine uroliths.11, 12, 13

In humans and dogs, cystinuria is caused by mutations in 1 of 2 genes, SLC3A1 and SLC7A9, which encode the polypeptide subunits of the bo,+ basic amino acid transporter system.1, 3 The SLC3A1 gene encodes a globular protein with a single transmembrane tail referred to as rBAT, whereas the SLC7A9 gene encodes an intramembrane transporter protein called bo,+AT protein. The COLA amino acid transporter is a heterotetramer formed from 2 heterodimers of bo,+AT and rBAT.14

Cystinuria in humans and dogs is classified into several types depending on age of onset, severity, sex, inheritance, and mutant gene.3, 15 In dogs, type I‐A and II‐A cystinuria are caused by SLC3A1 gene mutations and are autosomal recessively or dominantly inherited, respectively. In addition, type II‐B cystinuria is caused by SLC7A9 gene mutations and is autosomal dominantly inherited. The molecular basis for androgen‐dependent type (type III) cystinuria is unknown. We document here the first mutation known to cause cystinuria in the cat.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Samples

An intact male DSH cat from Torrington, Wyoming showed signs of dysuria, inappropriate urination, anorexia, and lethargy since 2 months of age. The stray kitten was found to have cystine crystals, and uroliths were surgically removed at 4 months of age. Quantitative crystallographic analysis by the Minnesota Urolith Center1 demonstrated that the uroliths were composed of 100% cystine. A family history was not available, and no further clinicopathological information was obtained. The cat was euthanized at 6 months of age because of urinary tract pain and neurological signs including lethargy and hypersalivation. Splenic tissue was sent frozen to the Metabolic Genetics Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania (PennGen). The studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania. As a feline control, 4 mL EDTA blood was collected from a healthy DSH cat. For genetic screening, buccal cytobrushes and EDTA blood samples remaining from a previous study and stored in our laboratory were available from 11 cats from Wyoming, and 53 DSH and domestic longhair (DLH) cats as well as purebred cats from other parts of the United States.

Molecular Genetic Studies

DNA Extraction and Amplification

Genomic DNA was extracted from splenic tissue of the cystinuric cat and from buccal swabs and EDTA blood samples from non‐cystinuric cats using DNA extraction kits.2 Genomic DNA covering all exons and intronic flanking regions (≥33 bp; average, approximately 100 bp) of the SLC3A1 gene based upon the Felis catus‐6.2 feline reference genome assembly (GenBank accession no.: AANG02047288.1 and AANG02047289.1) were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with exon flanking primers using specific annealing temperatures (Fig 1, Table S1). Each reaction mixture was prepared to a total volume of 50 μL containing 25 μL of 2X PCR master mix,3 0.625 μL each of the 50 μM forward and reverse primers, 21.25 μL of DNAse‐free water, and 2.5 μL of the DNA template sample.

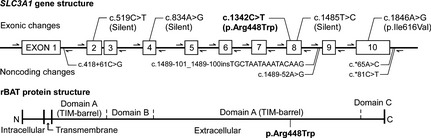

Figure 1.

The structure of the feline SLC3A1 gene, primer locations, and polymorphisms identified in a cystinuric cat. Exons are numbered and depicted by rectangles. Location and direction of primers used for PCR amplification and sequencing are indicated with arrows. The polymorphisms are shown at approximate locations in the SLC3A1 gene. The disease‐causing mutation is depicted with bold letters. Domains in the rBAT protein are shown at approximate locations in the coding region of the SLC3A1 gene. Arg, arginine; Trp, tryptophan; Ile, isoleucine; Val, valine; TIM, triosephosphate isomerase; N, N‐terminal; C, C‐terminal.

DNA Sequencing

Amplified products were separated using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The PCR products were purified with a gel extraction kit (QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit2) and were sequenced at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine's Core DNA Sequencing Facility using standard amplification primers. The sequences were compared to the feline reference sequence and the sequence from a healthy noncystinuric cat. All exonic and intronic flanking regions of the SLC3A1 gene were analyzed. Genetic nomenclature is in accordance with the Guidelines and Recommendations for Mutation Nomenclature by the Human Genome Variation Society.4

Protein Analysis

The deduced amino acid sequence for rBAT of the cystinuric cat was aligned with those of the healthy cat and other vertebrates using ClustalW.5 The protein sequence of the cystinuric cat was further assessed by SIFT6 to determine the effect of any amino acid polymorphisms and by membrane protein topology prediction servers including MESAT‐SVM,7 MESAT3,7 and OCTOPUS.8

Genotyping and Screening

A PCR‐ restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) and real‐time PCR assay were established to screen cats for each of the 2 missense sequence variants in exons 8 and 10 of the SLC3A1 gene, respectively. The exon 8 PCR product was digested for at least 2 hours at 37°C with the restriction enzyme NciI,9 and then separated by electrophoresis on a 6% polyacrylamide gel. For the real‐time PCR assay, allele specific TaqMan MGB probes10 and a dedicated primer pair were used to detect the polymorphism in exon 10 (Table S1).

Results

The coding sequence of the SLC3A1 gene of the healthy and cystinuric cat as well as the available feline reference sequence (Abyssinian cat) were nearly identical. When compared to the feline reference sequence, we observed 7 exonic and 18 noncoding SLC3A1 polymorphisms in the 2 sequences obtained (Fig 1, Table S2).

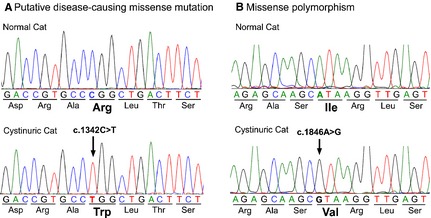

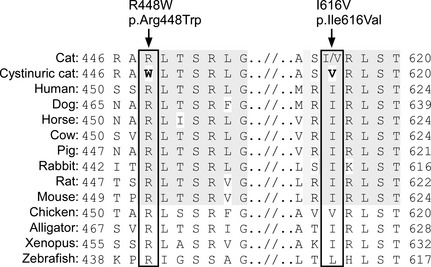

Of these variants, 2 were missense polymorphisms identified in the cystinuric cat. The most notable was c.1342C>T in exon 8 of the SLC3A1 gene, which causes an arginine to tryptophan substitution (p.Arg448Trp; Fig 2A). This arginine residue is highly conserved in vertebrates as evolutionarily distant as zebrafish (Fig 3). According to SIFT analysis, p.Arg448Trp is predicted to be very deleterious to the structure and function of the protein with a score of 0.00 (ranges from 0 to 1, with normal being 1 and unacceptable 0; a deleterious score is <0.05).6 Furthermore, according to MESAT3 and OCTOPUS analyses, p.Arg448Trp is predicted to introduce an additional transmembrane site into the extracellular domain of rBAT.

Figure 2.

Genomic DNA sequencing chromatograms of small regions of exons 8 and 10 of the SLC3A1 gene from a healthy and cystinuric cat. (A) Homozygous missense mutation (arrow) in the cystinuric cat. This single nucleotide substitution in exon 8 is unique to the cystinuric cat and is predicted to change the amino acid from arginine (Arg) to tryptophan (Trp). (B) Homozygous missense polymorphism. This single nucleotide substitution in exon 10 is predicted to change the amino acid from isoleucine (Ile) to valine (Val) and was seen in both cystinuric and healthy cats.

Figure 3.

The amino acid sequence homology of the feline SLC3A1 gene among species and the site of missense mutation and polymorphism (box). The mutation and polymorphism identified in a cystinuric cat indicated in boldface. The conserved areas among mammals are shaded. Arg and R, arginine; Trp and W, tryptophan; Ile and I, isoleucine; Val and V, valine.

The other missense variant in the cystinuric cat was c.1846A>G in exon 10 (Fig 2B). This polymorphism causes the substitution of an isoleucine for a valine residue (p.Ile616Val). This isoleucine residue resides in a relatively conserved region, but chickens also have a valine at this position (Fig 3). The amino acid change is predicted to be tolerated with a SIFT score of 0.33 and appears not to change the structure and function of rBAT.

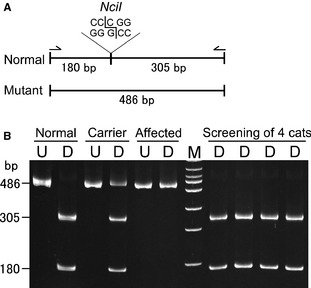

Genotype screening tests were used to determine the prevalence of these 2 missense variants in 64 DSH, DLH, and purebred cats from Torrington, Wyoming, and other parts of the United States. Using the PCR‐RFLP assay for exon 8, only the cystinuric proband in this study was found to have the c.1342C>T (p.Arg448Trp) mutant allele (Fig 4). On the other hand, the c.1846A>G (p.Ile616Val) polymorphism was discovered in other cats with an allele frequency of 0.49 (49%) by real‐time PCR assay; 17 cats were homozygous and 29 cats were heterozygous for the c.1846A>G change; both alleles were seen in different geographic areas and breeds. Because this amino acid substitution (p.Ile616Val) also was seen in other DSH, DLH, and purebred cats as well as chickens and the change is predicted to be well tolerated by protein model analyses, this variant was excluded as a disease‐causing mutation.

Figure 4.

A DNA test using a PCR‐restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) to screen for the missense (p.Arg448Trp) mutation in the SLC3A1 gene. (A) The amplified band is 486 bp in length, which is cleaved with the restriction enzyme NciI at 1 site producing 2 bands (305 and 180 bp) for the normal allele. The mutant allele is missing the restriction site, thus showing only 1 undigested band at 486 bp. Arrows indicate primers used for the PCR‐RFLP assay. (B) Polyacrylamide gel electrophoretogram of undigested and digested (NciI) PCR products differentiating normal, carrier and affected cats. The carrier sample was artificially produced by mixing aliquots of DNA from a normal and the cystinuric cat. The 4 digested samples on the right of the DNA marker represent genetic screening test results and all show normal genotype. Lanes: M, 100 bp DNA marker; U, undigested; D, digested; bp, base pair.

Discussion

Cystinuria is a common renal transport defect in dogs, occurring in >70 breeds,3 and is reported in 1 : 7,000 people.1 Although there is a large degree of genetic heterogeneity of cystinuria in both species, mutations in the SLC3A1 gene coding for rBAT are observed most commonly.1, 3 Because the SLC3A1 gene is highly conserved evolutionarily, we were able to identify the first mutation causing cystinuria in cats. Specifically, the cystinuric DSH cat studied here had a homozygous silent single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP; c.1342C>T) in the SLC3A1 gene that resulted in substitution of a highly conserved, positively charged, hydrophilic arginine for an aromatic, hydrophobic tryptophan residue (p.Arg448Trp). The amino acid residue at p.448 in feline rBAT aligns and is homologous to p.452 in humans (Fig 3). Interestingly, cystinuric humans have been found with missense mutations (p.Arg452Trp and p.Arg452Gln) at this rBAT protein position.16, 17 A Czech boy with severe urinary COLA excretion and cystine uroliths at 10 years of age was homozygous for the amino acid substitution (p.Arg452Trp).18 The 3 nucleotides (codon) encoding this arginine residue include CpG dinucleotides in both humans and cats. In this DNA region, cytosine resides next to guanine and DNA methylation commonly occurs. These sites are predisposed to new mutations because nucleotide changes arise more easily in regions with DNA methylation.19

Although SLC3A1 mutations can be manifested as either autosomal dominant or recessive traits in humans and dogs with cystinuria, most cases of cystinuria caused by SLC3A1 mutations are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.3, 15 In dogs, 2 SLC3A1 mutations result in early stop codons and cause an autosomal recessive type (I‐A) of cystinuria in Newfoundlands (Landseers) and Labrador retrievers. In addition, an autosomal codominant type (II‐A) of cystinuria is observed in Australian Cattle dogs because of a 2 codon deletion in the SLC3A1 gene (c.1095_1100del); the effect may be additive because homozygous dogs appear to be more severely affected than heterozygotes.3 Although family histories for the cystinuric cat in this study and the cystinuric Czech boy described above are unavailable, both had severe disease and were homozygous for the missense mutation, suggesting that this mutation conveys a recessive trait. In support of this hypothesis, heterozygous cystinuric patients with this mutation have not been described, although it is a common mutation in human cystinuria.15 According to a National Center for Biotechnology Information‐hosted public archive for genetic SNP variation, the allele frequency of p.Arg452Trp (rs201502095) is 0.002 based on results from the ClinSeq Project, which uses whole‐genome sequencing from approximately 1,000 participants as a tool for clinical research.20 Together, the data strongly suggest that the p.Arg452Trp (and thus feline p.Arg448Trp) substitution causes a recessive trait.

The feline SLC3A1 gene is composed of 10 exons (XM_003983937.2) and encodes a 681 amino acid rBAT protein (XP_003983986.1), which is slightly shorter than human and canine rBAT (685 and 700 amino acids, respectively). The rBAT amino acid sequence was 82 and 83% homologous to the canine and human sequence, respectively, with particularly low homology in the N‐terminal region. The rBAT protein encoded by SLC3A1 is expressed in the apical membrane of the epithelial cells in the proximal tubules and small intestine, and is composed of 3 main domains: intracellular, transmembrane, and extracellular (Fig 1).15 The extracellular domain includes a triosephosphate isomerase (TIM)‐barrel consisting of 8 helices and 8 parallel β‐strands.21 The arginine‐to‐tryptophan substitution resides in a coiled domain between the seventh β‐sheet and helix in the TIM‐barrel domain and is predicted by modeling programs to severely affect the structure and function of rBAT. Indeed, misfolding of rBAT because of mutations in the TIM‐barrel promotes rBAT degradation after its assembly with bo,+AT.22 Furthermore, based on its structure, the extracellular domain of rBAT is likely to contribute to its catalytic transport function.21 The most common mutation in human cystinuria patients is a p.Met467Thr substitution, which resides in a helix domain near the p.Arg452Trp mutation.21 Disease severity in these patients depends on additional mutations, because they are mostly compound heterozygotes. We speculate that the structural changes in the TIM‐barrel of rBAT directly contribute to abnormal transporter activity and degradation of rBAT in cystinuric patients bearing these mutations.

As in other species, cystinuria in cats causes urinary tract disease by promoting cystine calculi formation. Hematuria, dysuria, pollakiuria, urinary obstruction with postrenal failure or some combination of these are common signs.5 Cystine calculi in cats have been diagnosed between 4 months and 12 years of age, with a mean age of 3.6 years. The cat in this report was diagnosed with cystinuria as a kitten and thus had a severe type of cystinuria similar to that has been reported dogs with type I‐A cystinuria.3 Cystinuric cats with a later onset of clinical signs may have a milder degree of cystinuria as a result of less deleterious renal cystine transporter mutations.18 Although renal cystine calculi have been reported in cystinuric humans and Newfoundlands (Landseers), all cystine uroliths in cats have been found in the lower urinary tract.

The cats in this study and in the original case report of feline cystinuria were males but in a reported case series, 9 of 17 cystinuric cats were females.4, 5 In humans, the incidence of cystinuria is equal between sexes, but male patients are more severely affected than female patients.23 The consequences of cystinuria also tend to be more severe in male dogs because of their longer and narrower urethra and the os penis, which favors obstruction by calculi. Interestingly, an androgen‐dependent type of cystinuria (type III) that is exclusively seen in mature intact male dogs recently has been discovered in several breeds of dogs, and castration is curative.3, 10

In addition to clinical signs of lower urinary tract disease common among all cystinuric animals, cystinuric cats often show other signs such as hypersalivation, lethargy, and even seizures. Although the cause of these signs is unknown, we suspect that they are caused by secondary hyperammonemia arising from impaired intestinal absorption and excessive renal excretion of COLAs. Arginine deficiency can result in hyperammonemia in cats. In most other mammals including humans, rats, and dogs, arginine is synthesized from citrulline.24, 25 When blood ammonia concentration increase, citrulline production in the small intestine is accelerated. This allows the urea cycle to continue to metabolize ammonia even when arginine is excreted in the urine or the diet is deficient in arginine. In contrast, cats cannot synthesize citrulline in the intestine because of low activity of ornithine aminotransferase and pyrroline‐5‐carboxylate synthase, and are deficient in arginine biosynthesis. As such, cats are completely dependent on dietary arginine intake and renal arginine resorption.25 It follows that cystinuric cats with impaired intestinal absorption and renal reabsorption of arginine would become arginine deficient, which then could lead to hyperammonemia and neurological signs. Although blood arginine and ammonia concentrations were not measured in the cystinuric cat studied here, the clinical signs were consistent with hyperammonemia. Indeed, these potentially fatal complications may occur before cystine calculi develop, which may in part explain the rare documentation of cystinuria in cats.

Medical, dietary, and surgical treatment options have been described for in humans and dogs with cystinuria, but they have not been described for cystinuric cats.1, 26 As with other types of calculi, it is likely helpful to dilute the urine by adequate intake of fluid. Because cystine solubility increases rapidly above pH 7.5, urinary alkalinization with potassium citrate along with forced diuresis are recommended. 2‐Mercaptopropionylglycine (2‐MPG) and D‐penicillamine are cystine chelating agents that have been used in cystinuric dogs and people, but not in cats, and thus these drugs should be used with great caution because of the potential for adverse effects. Castration cannot only be curative for androgen‐dependent cystinuria in some dog breeds but also has beneficial effects in other breeds of dogs by decreasing prostate size, decreasing urinary tract infections, and improving urine voiding patterns. Special dietary formulations with decreased protein, methionine and cystine content and those that enhance alkalinization of urine are recommended. In humans, arginine restriction has been recommended. However, in the case of feline cystinuria, potential life‐threatening arginine deficiencies clearly need to be considered and can be prevented with an arginine‐rich diet or arginine supplementation.

To determine the prevalence of the SLC3A1 p.Arg448Trp mutation, we developed a DNA PCR‐RFLP test that could clearly discriminate all 3 genotypes (Fig 4). Only a small number of cats have been surveyed, and no other cats homozygous or heterozygous for the mutation have been identified. It is possible that it is a relatively new geographically restricted mutation. Because only 11 cats from Wyoming were studied, we could not determine how common the mutation is in that geographic area. We recently screened 5 other cystinuric cats for the mutation and none had it (K. Mizukami, K. Raj, and U. Giger, unpublished). Therefore, cystinuric cats from other geographic locations likely have other SLC3A1 or even SLC7A9 mutations as recently reported in Miniature Pinschers with cystinuria from Europe.3 Consequently, veterinarians cannot rule out cystinuria by the absence of this mutation and must make a diagnosis based on the results of other tests including microscopic examination of urine for hexagonal cystine crystals, crystallographic urolith analysis, the cyanide‐nitroprusside test, and quantitative analysis of COLA in the urine.

In conclusion, this study identifies the first causative mutation in a cat with cystinuria. The identified homozygous missense mutation in the feline SLC3A1 gene previously has been identified in humans with cystinuria. Although this mutation apparently is not common among cystinuric cats, our finding could be used to characterize other cystinuric cats at the molecular level.

Supporting information

Table S1. Primer and probe pairs, length of DNA product, and annealing temperatures used for the amplification of the SLC3A1 exons and real‐time PCR assays.

Table S2. Polymorphisms in exons and the flanking intronic regions of the SLC3A1 gene identified in a healthy and a cystinuric cat.

Acknowledgments

We thank the referring technician Ms. Jamie Michael and the Goshen Veterinary Clinic Torrington, WY for samples from a cystinuric and other cats. This study was supported in part by a grant from the NIH # OD 010939, and Keijiro Mizukami was the recipient of a research fellowship for young scientists from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Off‐label Antimicrobial Declaration: The authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

This study was performed at the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN, http://www.cvm.umn.edu/depts/minnesotaurolithcenter/

DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit, QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany

GoTaq Hot Start Green Master Mix, Promega Corp., Madison, WI

New England Biolabs inc., Ipswich, MA

Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA

References

- 1. Palacin M, Goodyer P, Nunes V, Gasparini P. Cystinuria In: Valle D, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Antonarakis SE, Ballabio A, Gibson KM, Mitchell G, Scriver CR, Sly WS, Beaudet AL, Bunz F, eds. The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill Medical; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henthorn PS, Giger U. Cystinuria In: Ostrander EA, Giger U, Lindblad‐Toh K, eds. Cold Spring Harbor Monograph Series: The dog and Its Genome. New York, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2006:349–364. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brons AK, Henthorn PS, Raj K, et al. SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 mutations in autosomal recessive or dominant canine cystinuria: A new classification system. J Vet Intern Med 2013;27:1400–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. DiBartola SP, Chew DJ, Horton ML. Cystinuria in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991;198:102–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osborne CA, Lulich JP, Sanderson S, et al. Feline cystine urolithiasis – 18 cases. Feline Pract 1999;27:31–32. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nwaokorie EE, Osborne CA, Lulich JP, Albasan H. Epidemiological evaluation of cystine urolithiasis in domestic ferrets (Mustela putorius furo): 70 cases (1992–2009). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013;242:1099–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peters T, Thaete C, Wolf S, et al. A mouse model for cystinuria type I. Hum Mol Genet 2003;12:2109–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bush M, Bovee KC. Cystinuria in a maned wolf. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1978;173:1159–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jackson OF, Jones DM. Cystine calculi in a caracal lynx (Felis caracal). J Comp Pathol 1979;89:39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giger U, Brons AK, Fitzgerald CA, et al. Updates on cystinuria and fanconi syndrome: amino acidurias in dogs. Proceedings of the 2014 American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine Forum; 2014 June 4–7; Nashville, TN. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Houston DM, Moore AE. Canine and feline urolithiasis: Examination of over 50 000 urolith submissions to the canadian veterinary urolith centre from 1998 to 2008. Can Vet J 2009;50:1263–1268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Albasan H, Osborne CA, Lulich JP, Lekcharoensuk C. Risk factors for urate uroliths in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2012;240:842–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Osborne CA, Lulich JP, Kruger JM, et al. Analysis of 451,891 canine uroliths, feline uroliths, and feline urethral plugs from 1981 to 2007: Perspectives from the Minnesota Urolith Center. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2009;39:183–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fernandez E, Carrascal M, Rousaud F, et al. rBAT‐b(0,+)AT heterodimer is the main apical reabsorption system for cystine in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2002;283:F540–F548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eggermann T, Venghaus A, Zerres K. Cystinuria: An inborn cause of urolithiasis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012;7:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bisceglia L, Purroy J, Jimenez‐Vidal M, et al. Cystinuria type I: Identification of eight new mutations in SLC3A1 . Kidney Int 2001;59:1250–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Endsley JK, Phillips JA 3rd, Hruska KA, et al. Genomic organization of a human cystine transporter gene (SLC3A1) and identification of novel mutations causing cystinuria. Kidney Int 1997;51:1893–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Skopkova Z, Hrabincova E, Stastna S, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 genes in Czech and Slovak cystinuric patients. Ann Hum Genet 2005;69:501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barker D, Schafer M, White R. Restriction sites containing CpG show a higher frequency of polymorphism in human DNA. Cell 1984;36:131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Biesecker LG, Mullikin JC, Facio FM, et al. The ClinSeq project: Piloting large‐scale genome sequencing for research in genomic medicine. Genome Res 2009;19:1665–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Broer S, Wagner CA. Structure‐function relationships of heterodimeric amino acid transporters. Cell Biochem Biophys 2002;36:155–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bartoccioni P, Rius M, Zorzano A, et al. Distinct classes of trafficking rBAT mutants cause the type I cystinuria phenotype. Hum Mol Genet 2008;17:1845–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saravakos P, Kokkinou V, Giannatos E. Cystinuria: Current diagnosis and management. Urology 2014;83:693–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kohler ES, Sankaranarayanan S, van Ginneken CJ, et al. The human neonatal small intestine has the potential for arginine synthesis; developmental changes in the expression of arginine‐synthesizing and ‐catabolizing enzymes. BMC Dev Biol 2008;8:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Morris JG. Nutritional and metabolic responses to arginine deficiency in carnivores. J Nutr 1985;115:524–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chew DJ, Dibartola SP, Schenck PA. Urolithiasis In: Canine and Feline Nephrology and Urology, 2nd ed St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Inc.; 2010:272–305. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Primer and probe pairs, length of DNA product, and annealing temperatures used for the amplification of the SLC3A1 exons and real‐time PCR assays.

Table S2. Polymorphisms in exons and the flanking intronic regions of the SLC3A1 gene identified in a healthy and a cystinuric cat.