Abstract

People’s social and political opinions are grounded in their moral concerns about right and wrong. We examine whether five moral foundations—harm, fairness, ingroup, authority, and purity—can influence political attitudes of liberals and conservatives across a variety of issues. Framing issues using moral foundations may change political attitudes in at least two possible ways: 1. Entrenching: relevant moral foundations will strengthen existing political attitudes when framing pro-attitudinal issues (e.g., conservatives exposed to a free-market economic stance). 2. Persuasion: mere presence of relevant moral foundations may also alter political attitudes in counter-attitudinal directions (e.g., conservatives exposed to an economic regulation stance). Studies 1 and 2 support the entrenching hypothesis. Relevant moral foundation-based frames bolstered political attitudes for conservatives (Study 1) and liberals (Study 2). Only Study 2 partially supports the persuasion hypothesis. Conservative-relevant moral frames of liberal issues increased conservatives’ liberal attitudes.

Keywords: morality, moral foundations, ideology, attitudes, politics

Our daily lives are steeped in political content, including many attempts to alter our attitudes. These efforts stem from a variety of sources, such as political campaigns, presidential addresses, media articles, or our social network, and they comprise topics ranging from the national economy to neighborhood safety. While social and political psychologists generally know much about persuasion (Cialdini, 2008; Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), we know less about how morally-based appeals can alter people’s sociopolitical opinions.

However, a variety of research clearly shows that morality matters. People’s social and political attitudes are often based on their moral concerns (e.g., Bobocel, Son Hing, Davey, Stanley, & Zanna, 1998; Emler, 2002; Haidt, 2001; Haidt, 2012; Skitka, 2002). For example, strong feelings of right or wrong may guide citizens’ support for policies and candidates (Skitka & Bauman, 2008). As suggested by theory, individuals should ground their social and political beliefs on moral foundations, such as notions of harm, fairness, or purity (e.g., Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009;Haidt & Graham, 2007).

Questions remain, however, as to whether moral foundations can causally alter degree of support for political positions and policies, and whether this varies for liberals and conservatives (Haidt, 2012; Haidt & Graham, 2007; Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto, & Haidt, 2012; Markowitz & Shariff, 2012).Understanding the effectiveness of morally-based framing may be consequential not only for politics, but also for better understanding everyday shifts in other opinions. The present research examines whether moral foundations may, in part, underlie changes in the political attitudes of liberals and conservatives.

Accumulating cross-cultural evidence suggests that beliefs about moral right or wrong are based on more than concerns for harm and fairness (Haidt, 2007; Haidt & Graham, 2007). Building on the morality-relevant research of anthropologists (e.g., A. P. Fiske, 1991; Shweder, Mahapatra, & Miller, 1987) and psychologists (e.g., Kohlberg, 1969; Schwartz, 1992; Turiel, 1983), as well as evolutionary theorizing and evidence, Haidt and colleagues have proposed that at least five foundations make up morality: harm, fairness, ingroup, authority, and purity (Graham et al., 2013; Haidt & Graham, 2007; Haidt & Joseph, 2007, 2004).1 The harm foundation is broadly based on human sensitivity to prevent suffering, and to empathize and care for others. The fairness foundation encompasses notions of justice, inequality, reciprocity, and general unbiased treatment. The ingroup moral foundation prioritizes loyalty and a group-based orientation, such as thinking in terms of “we.” The authority foundation involves valuing traditions, hierarchical social orders, and respecting those with power. The purity foundation focuses on disgust sensitivity, an appreciation for an elevated way of life, and a concern for cultural sacredness (for a review of moral foundations, see Haidt, 2012; Haidt & Graham, 2007).

Consistent with the notion that groups tend to share moral bases of their beliefs (Haidt, 2007), liberals tend to rely more heavily on the harm and fairness moral foundations, whereas conservatives tend to rely more on the ingroup, authority, and purity moral foundations (Graham et al., 2009; Haidt & Graham, 2007). For instance, liberals are more likely to explicitly agree with moral and political statements that concern harm (e.g., compassion for those who are suffering is the most crucial virtue) and fairness (e.g., when making laws, the number one principle should be ensuring fair treatment), than the other three moral foundations. Conservatives are more likely to agree with statements that reference ingroup loyalty (e.g., loyalty to one’s group is more important than one’s individual concerns), authority (e.g., lawmakers should respect traditions), and purity (e.g., the government should help people live virtuously), compared with the other two moral foundations (Graham, et al., 2009).2 In other words, political orientation appears to reflect the moral foundations that are considered most relevant. Although moral references, including moral foundations, have been documented in social and political rhetoric (e.g., Graham et al., 2009; Haidt, 2012; Lakoff, 2002), such contexts rarely test the causal consequences of moral foundations. We suggest that altering the evoked moral foundations may shape people’s subsequent attitudes, particularly if the moral foundations seem relevant.

When examining whether relevant moral foundations can affect political attitudes, we also consider the role of one’s prior views. Evidence suggests that political orientation is a reasonably good predictor of people’s political attitudes (e.g., Jacoby, 1991; Jost, 2006). For example, those with a more liberal orientation more likely favor policies that expand social programs, whereas those with a more conservative orientation more likely endorse policies that hold social-program users accountable.3 Additionally, whether a particular stance on an issue is consistent with one’s views (i.e., pro-attitudinal) or inconsistent with one’s views (i.e., counter-attitudinal) is pivotal to research on persuasion (e.g., Clark, Wegener, & Fabrigar, 2008a, 2008b). Research on motivated reasoning also indicates that people’s prior views can bias beliefs and judgments (Ditto & Lopez, 1992; Kunda, 1990; Mercier & Sperber, 2011), including in sociopolitical domains (Bartels, 2002; Crawford & Pilanski, 2013; Jost & Amodio, 2012; Lord, Ross, & Lepper, 1979; Pomerantz, Chaiken, & Tordesillas, 1995; Redlawsk, 2002; Taber & Lodge, 2006). For instance, those with a more conservative orientation may be more receptive and less critical of a stance on an issue if it is pro-attitudinal, as compared to a stance that is counter-attitudinal. Likewise, liberals may show openness to liberal pro-attitudinal standpoints and bias against counter-attitudinal views.

Building on these notions, the present research examines the effects of the five moral foundations (harm, fairness, ingroup, authority, purity) on the political attitudes of liberals and conservatives, for pro-attitudinal and counter-attitudinal stances on issues. We located only one prior study that has partly investigated these factors, specifically, the effect of harm and purity-based frames on conservatives’ and liberals’ pro-environmental attitudes (Feinberg & Willer, 2012, Study 3). By varying the content of ostensible newspaper articles, conservatives’ pro-environmental attitudes increased after exposure to a purity frame (i.e., a conservative-relevant moral foundation), but not following a harm frame (i.e., a liberal-relevant moral foundation). Liberals’ attitudes did not change following the harm or purity manipulations (Feinberg & Willer, 2012). This research documents differential effects of some moral frames for liberals and conservatives, for a liberal pro-attitudinal stance on an issue.

Although encouraging, considerable questions remain. For instance, it is unclear whether effects would emerge if the stance on the topic were pro-attitudinal for conservatives (as opposed to for liberals), if all five of the moral foundations were employed, or if other sociopolitical issues beyond the environment were examined. In other words, can relevant moral foundation-based frames broadly persuade liberals to hold more conservative attitudes, and conservatives to hold more liberal attitudes? Will moral frames instead entrench existing attitudes? Or will there be no consistent effects? The present research is designed to answer these questions and thus broaden our understanding of the implications of moral foundations in political persuasion. Next we outline our research plan, as well as our hypothesized effects of the moral foundation framings.

Two studies test for effects of moral frames on liberals’ and conservatives’ attitudes. Study 1 examines both liberals’ and conservatives’ attitudes following exposure to conservative pro-attitudinal stances on issues (e.g., less economic regulation), variously framed based on the five moral foundations. Study 2 examines liberals’ and conservatives’ attitudes following exposure to liberal pro-attitudinal stances on the same issues (e.g., more economic regulation) that are variously framed using the same moral foundation framework. Each study assesses political attitudes after exposure to moral framing.

We employ methods consistent with engaging both the peripheral and central routes of persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986;Petty & Wegener, 1999). Specifically, in addition to subtly framing issues using moral foundations (i.e., peripheral exposure to moral frames), participants are asked to create their own supporting points for each morally framed issue (i.e., effortful contemplation of issues associated with the central route). This also coincides with the possibility that moral frames may shape attitudes by activating individuals’ moral intuitions either immediately or through more deliberative processes (Haidt, 2001). We consider these and related processes through exploratory analyses in each study and further in the General Discussion. We also examine a range of potential effects of the moral foundations; thus, both studies test our hypotheses using a variety of issues.

While the five moral foundations provide a useful framework to examine changes in political attitudes, moral foundations theory does not offer specific predictions on how moral frames may affect political attitudes for conservatives and liberals across issues. Thus, based on relevant research, we have adopted two broad hypotheses about possible moral foundation patterns that may emerge across studies. These hypotheses are complementary, but differ in the type of presumed impact of the moral foundations on political attitudes.

The first possibility, the entrenching hypothesis, presumes a limited effect of moral foundation-based frames on changing the direction of political attitudes. This hypothesis rests on the assumption that people tend to protect their political attitudes and not be readily open to persuasion attempts (e.g., Kunda, 1990; Lord et al., 1979). However, this hypothesis also expects that people’s political attitudes can change (e.g., Bryan, Dweck, Ross, Kay, & Mislavsky, 2008; Cohen, 2003; Jost, 2006; Landau et al., 2004; Munro, Zirpoli, Schuman, & Taulbee, 2013; Oppenheimer & Trail, 2010). Specifically, people’s existing attitudes may increase after exposure only to relevant moral frames of pro-attitudinal issues. For example, conservatives’ attitudes may become more conservative following exposure to a purity frame (i.e., a relevant moral foundation) of a stance on reducing economic regulation (i.e., a relatively conservative view). In other words, this hypothesis specifies conditions in which moral framing may entrench existing views.

We believe that attitudes may become entrenched under these conditions because moral frames may especially activate individuals’ moral intuitions (Haidt, 2001). Moreover, existing attitudes may increase because morally framed information may be less critically evaluated when it is pro-attitudinal, consistent with research on motivated reasoning (e.g., Kunda, 1990; Taber & Lodge, 2006). In addition, thinking about a framed position, particularly when familiar or relevant morally, may further polarize attitudes (Petty & Cacioppo, 1979; Tesser & Conlee, 1975). The entrenching hypothesis also fits research that shows information is processed more easily and is more convincing when the message “feels right” (Cesario, Grant, & Higgins, 2004; Lee & Aaker, 2004), such as when exposed to an issue consistent with one’s views that is framed using a moral foundation that one finds relevant.

The second hypothesis, the persuasion hypothesis, harnesses much of the same general logic and rationale as the entrenching hypothesis, but presumes that the moral foundations will have a greater directional impact. Although individuals may not easily adopt opposing political attitudes, the presence of moral foundations may increase the likelihood of this possibility. Specifically, the persuasion hypothesis holds that if moral foundations have stronger effects, then exposure to relevant moral frames may shift political attitudes even when stances on issues are counter-attitudinal (e.g., conservatives and economic regulation). As participants in the present research have the opportunity to tailor their own supporting points for morally framed issues (Noar, Benac, & Harris, 2007), relevant moral frames may shape participants’ effortful consideration of issues. Such conditions may lead to persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Although there is theoretical support for the persuasion hypothesis, we acknowledge that moral foundations may have difficulty to alter attitudes “across a moral divide” (Haidt, 2012, p.49), even if the moral frames appeal to individuals’ moral intuitions (Haidt, 2001). Together, our two studies fully test these hypotheses.

Study 1: Conservative Stances on Issues

Method

Participants

A sample of 706 American residents volunteered for a study of “Perspectives on Current Issues” using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011; Paolacci & Chandler, 2014).4 The study was completed by 628 participants who were each remunerated with $1.25. The descriptive writing demands may have, in part, contributed to a modest rate of attrition (11.0%). Political orientations of participants who completed the study were as follows: 49.0% liberal, 17.5% moderate, 24.7% conservative, 3.7% libertarian, 3.2% do not know, and 1.6% undisclosed. Consistent with past research (e.g., Graham et al., 2009, Study 3), we were interested in examining only participants who identified along the liberal-conservative political spectrum (1 = very liberal, 2 = liberal, 3 = slightly liberal, 4 = moderate/middle of the road, 5 = slightly conservative, 6 = conservative, 7 = very conservative), so we excluded alternative responders (8 = libertarian, 9 = do not know, and undisclosed). Four participants were also removed for not following instructions. Altogether, the effective sample size was 569 participants (52.4% women, Mage = 35.61, SD = 12.63). Ethnic groups included: 78.9% White, 8.1% Black, 6.2% Hispanic, 4.2% Asian, 1.2% Native American, 0.2% Middle Eastern, 1.1% Other, and 0.2% undisclosed. The sample was well-educated (e.g., 34.6% Some college/Associate degree, 35.1% Bachelor’s, 14.8% Master’s, 4.0% Professional/PhD), reported to be almost average on a 10-point measure of subjective socioeconomic status, M = 5.08, SD = 1.83, and was slightly left of the mid-point on the seven-point liberal-conservative scale, M = 3.46, SD = 1.78.

Design and Procedure

This study aimed to test whether exposure to moral foundation-based frames of conservative stances on issues affect political attitudes. Our central manipulation was exposure to moral frames either before or after measurement of political attitudes. We randomly assigned participants to the moral frame or control condition.

In the moral frame condition we exposed each participant to all five moral foundation-based frames (harm, fairness, ingroup, authority, purity). To assess a broad impact of moral framing, the moral frames were applied to stances on five issues (immigration, the environment, economic markets, social programs, and education) that spanned the socio-political sphere but that were not extremely controversial (e.g., not abortion). All stances on these issues in Study 1 were designed to be pro-attitudinal for conservatives (and thus counter-attitudinal for liberals).

To expose participants to the five moral frames and five political issues, we employed a 5×5 Latin Square design. This design allowed all participants in the moral frame condition to view moral frames based on each moral foundation and each issue. That is, each participant was exposed to five moral frame-issue pairings, in one of five combinations of frames and issues as indicated by the Latin Square. Across participants, this design completely balances frames and issues. In the moral frame condition, participants were asked to create good arguments that supported each stance on the issues they encountered, ostensibly to help create materials for future studies on people’s opinions of current topics. Moreover, participants were asked to complete this task for two stances for each of the five issues. Both of these stances were from the same moral frame and issue combination. For example, suppose a participant was assigned to view a fairness-framed stance on immigration. After viewing one stance, the participant would write 2-3 supporting points, then view another fairness-framed stance on immigration, and subsequently write supporting points. The cycle would then repeat for the next moral frame of a different issue, which would be assigned based on the Latin Square. Thus, each participant was exposed to 10 stances (two for each moral frame-issue pair). Two stances on issues were used in this way to increase the opportunity that moral frames could have an impact on political attitudes by having participants more thoroughly deliberate on morally framed issues, and thus engage in central route processing (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Afterwards, participants in the moral frame condition completed the political issues questionnaire.

In the control condition, participants first completed the political issues questionnaire, followed by the moral-frame writing task. Participants in both conditions completed demographic questions (e.g., age, gender, education, political orientation, subjective SES), before finally being debriefed.

Materials

Each participant saw ten morally-framed stances on issues that came from a bank of 50 stances.5 Broadly, the conservative stances on the five issues were as follows: citizens should be prioritized ahead of immigrants; higher priorities exist than the environment; economic markets should operate more freely; social programs are misused and wasteful; there should be more choice in educating children. The following are five examples of morally framed conservative stances:

Education/Harm: We must care for our children by having the freedom to put them in schools that match their parents’ wishes.

Immigration/Fairness: It is only fair to preserve the rights of long-term citizens ahead of recent immigrants.

Economic Markets/Ingroup: Economic freedom is a cornerstone of what it means to be American.

Social Programs/Authority: Authorities should not allow people to live off the system.

Environment/Purity: Our way of life is sacred, and should not be sacrificed by new environmental policies.

Pilot test participants (N = 127) were recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and randomly assigned to rate how much a particular moral foundation (harm, fairness, ingroup, authority, or purity) was reflected in each of the 50 stances. Results indicated that the moral language embedded in these stances on issues best reflected the intended moral foundation (all t’s > 2.0, p’s < .06).

Measures

We evaluated political attitudes using a 10-item political-issues questionnaire (see online Appendix). The questionnaire included two questions related to each of the five issues: one item was worded in conservative terms (e.g., for economic markets: “The economic market will naturally correct itself”), while the other item was worded in liberal terms (e.g., “The federal government must regulate the economy”). Participants were asked to indicate how much they disagreed or agreed with each statement (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Scores on the liberally worded items were reverse-coded to create index scores for conservative responses on each issue. Correlations between item-pairs for the same issue had a median of r = .46 (range: r (565) = .32, p < .001, to r (565) = .64, p < .001). In addition to answers of the political-issues questionnaire, we also saved the free-response arguments from the writing task for exploratory linguistic analysis.

Results

Prior to analyses, the five political issue index scores were each standardized within issue to control for different overall attitudes toward particular issues. Next, based on participants’ Latin Square condition, we used the appropriate political-issue index scores to create political attitude scores for each moral foundation (i.e., harm, fairness, in group, authority, purity). For example, if a participant received immigration stances framed in terms of harm, the relevant score for the harm foundation would be that person’s immigration political issue index score. Consistent with the political issues questionnaire, higher scores indicate more conservative political attitudes and lower scores indicate more liberal attitudes.

As a reminder of our predictions, our entrenching hypothesis predicts that the moral foundation-based frames will increase conservative attitudes, in particular for conservatives exposed to conservative-relevant moral frames (ingroup, authority, purity), as compared to conservatives not exposed to any moral frames. The moral frames may have even stronger effects. Based on this possibility, the persuasion hypothesis predicts that not only will conservatives increase their conservative attitudes when exposed to relevant moral frames, but liberals, when exposed to liberal-relevant moral frames (harm, fairness), may also shift their views in support of the conservative pro-attitudinal stances.

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) on the five moral foundation scores. In this analysis, framing was our between-condition factor (no-frame control vs. moral frame), and participants’ political orientation (mean-centered) was a continuous factor.6 We included both factors and their interaction term in the model. Results revealed a main effect of political orientation, F(5,561) = 85.50, p < .001, ηp2 = .43, but the main effect of moral frame (vs. control) was not significant, F(5,561) = 1.97, p = .08, ηp2 = .02.

More importantly, the overall multivariate interaction between frame and political orientation for the five moral foundation scores was significant, F(5,561) = 2.55, p = .03, ηp2 = .02.7 To decompose this interaction, we conducted separate multiple regressions for each moral foundation political-attitude score. On the first step for each frame, we examined the effects of moral frames (0 = control, 1 = moral frame)and political orientation (mean-centered). On the second step we added the interaction term. We interpreted the results of the first step, unless adding the interaction term led to a significant increase in explained variance (i.e., change in R2), in which case we interpreted the results of the second step. See Table 1 for results of these regressions for each moral foundation frame, and Figure 1 for graphs of these results. We report 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for these main findings.

Table 1.

Regressions of Conservative Attitudes Depending on Exposure to Conservative Stances on Issues Framed by Five Moral Foundations and Political Orientation, Study 1

| Step 1 | Harm

|

Fairness

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | t | b | SE | β | t | |||||

| Political Orientation | .26 | .02 | .46 | 12.31*** | .26 | .02 | .48 | 13.15*** | ||||

| Frame | .12 | .07 | .06 | 1.65 | .01 | .07 | .01 | 0.13 | ||||

| Constant | -.03 | -.08 | ||||||||||

| R2 | .217*** | .235*** | ||||||||||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Political Orientation | .26 | .03 | .48 | 8.94*** | .23 | .03 | .42 | 8.04*** | ||||

| Frame | .12 | .07 | .06 | 1.64 | .01 | .07 | .01 | 0.13 | ||||

| Political O. x Frame | -.02 | .04 | .-02 | -0.46 | .07 | .04 | .09 | 1.66 | ||||

| Constant | -.02 | -.08 | ||||||||||

| ΔR2 | .000 | .004 | ||||||||||

| Ingroup

|

Authority

|

Purity

|

||||||||||

| Step 1 | b | SE | β | t | b | SE | β | t | b | SE | β | t |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Political Orientation | .25 | .02 | .46 | 12.22*** | .27 | .02 | .47 | 12.84*** | .27 | .02 | .46 | 12.32*** |

| Frame | .04 | .07 | .02 | 0.59 | .21 | .07 | .11 | 2.88** | .08 | .08 | .04 | 1.08 |

| Constant | .01 | -.06 | -.07 | |||||||||

| R2 | .211*** | .239*** | .215*** | |||||||||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Political Orientation | .25 | .03 | .46 | 8.52*** | .22 | .03 | .38 | 7.31*** | .22 | .03 | .37 | 7.04*** |

| Frame | .04 | .07 | .02 | 0.59 | .21 | .07 | .11 | 2.89** | .08 | .08 | .04 | 1.09 |

| Political O. x Frame | .00 | .04 | .00 | 0.03 | .10 | .04 | .13 | 2.41* | .10 | .04 | .12 | 2.27* |

| Constant | .01 | -.06 | -.07 | |||||||||

| ΔR2 | .000 | .008* | .007* | |||||||||

Note:

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

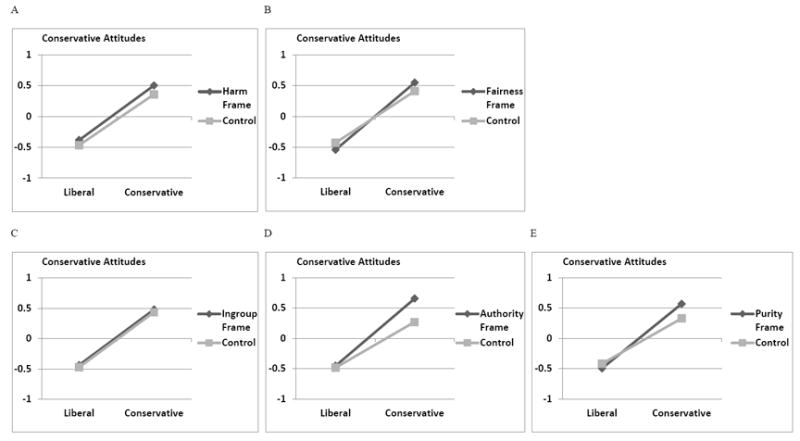

Figure 1.

Mean conservative attitudes depending on political orientation and exposure to moral foundation frames of conservative stances, Study 1. Liberal and conservative means represent 1 SD below and above the mean political orientation, respectively. Each moral foundation is graphed separately. A: Harm; B: Fairness; C: Ingroup; D: Authority; E: Purity.

First, we examined the liberal-relevant harm and fairness moral foundations. For the harm foundation, the first step revealed that political orientation predicted political attitudes, b = .26 (CI: .21, .30), p < .001. The positive association shows that those with a more conservative orientation endorsed more conservative political attitudes than those with a more liberal orientation, regardless of the control vs. liberal (harm) frame (see Figure 1A). This indicates that the issues we included in our political-attitude index reflected liberal and conservative viewpoints as rated by liberals and conservatives. (This is also evident in the positive slopes observed for the other moral frames in Figure 1B-E). In this harm regression we found no significant effect of the frame manipulation, b = .12 (CI: -.02, .27), p = .10. On the second step, we also did not find an interaction between these factors, b = -.02 (CI: -.10, .06), p = .64. For the fairness foundation, again, political orientation predicted political attitudes, b = .26 (CI: .23, .30), p < .001, but there was no effect of the fairness frame, b = .01 (CI: -.13, .15), p = .90, and no significant interaction, b = .07 (CI: -.01, .15), p = .10 (see Figure 1B). As liberals’ attitudes were relatively unaffected by either of the liberal-relevant moral foundations, these results do not provide support for the persuasion hypothesis.

We next examined moral foundations more relevant to conservatives. For the ingroup-loyalty moral-foundation framing, we found an overall association between political orientation and conservative attitudes, b = .25 (CI: .21, .30), p < .001, but no effect of ingroup frame, b = .02 (CI: -.02, .27), p = .56. The interaction was also not significant, b = .00 (CI: -.08, .08), p = .98. However, for the authority foundation, we found not only a significant effect of political orientation, b = .27 (CI: .22, .31), p < .001, but also of authority frame (vs. control), b = .21 (CI: .07, .36), p = .004, as well as a significant interaction between these factors, b = .10 (CI: .02, .18), p = .02 (see Figure 1D). Contrasts revealed that for those self-identifying as more conservative (i.e., +1 SD on the political orientation measure), the authority frame increased conservative attitudes compared to the control condition, b = .39 (CI: .18, .59), p < .001. There was no significant difference between conditions for those identifying as more liberal (i.e., -1 SD), b = .04 (CI: -.17, .24), p = .73. For the purity moral foundation, we found a similar pattern of results. Political orientation predicted conservative attitudes, b = .27 (CI: .22, .31), p < .001, but moral frame alone did not, b = .08 (CI: -.07, .24), p = .28. However, the overall interaction was significant, b = .10 (CI: .01, .18), p = .02 (see Figure 1E). Relative to the control condition, follow-up contrasts revealed that the purity moral frame increased conservative attitudes for conservatives, b = .26 (CI: .04, .47), p = .02, but there was no between-condition effect of the purity frame for liberals, b = -.09 (CI: -.33, .12), p = .40. Thus, two of the three conservative-relevant moral foundations increased conservatives’ attitudes, consistent with the entrenching hypothesis.

In secondary, exploratory analyses, we also analyzed the content of participants’ written responses in the experimental condition. These analyses served two purposes: 1) to examine whether the moral frames embedded in the stances affected what participants wrote, and 2) to test whether the degree of moral foundation content detected could help explain participants’ political attitudes. First, we examined how much each written response (10 responses per participant, 2 for each of 5 frames) contained each of the five moral foundations using the Linguistic Inquiry Word Count program (LIWC; Pennebaker, Booth, & Francis, 2007). Consistent with the LIWC procedures, we cleaned the 2,710 responses (e.g., spelling errors were corrected). Next, we analyzed responses using a moral foundations dictionary that contained 295 word-stems representing the five moral foundations (for details on the creation and content of this dictionary, see Graham et al., 2009, Study 4). Prior to analyses we removed one word-stem from the Authority list (immigra*), because immigration was one of the five issues examined. The LIWC analyses provided the frequency that each moral foundation was present of the total words per response. As participants wrote two responses for each moral foundation-issue cell, we averaged these response scores, which resulted in five moral foundation frequency scores for each moral foundation frame.

Next, we examined whether the manipulated moral foundation frames led to higher frequencies of moral foundation content in a participant’s relevant responses. For example, after exposure to a harm-framed issue, did participants make more references to the harm foundation as compared to the frequencies of harm-related words following other moral frames (e.g., fairness, ingroup)? We conducted repeated measures ANOVAs comparing the frequency of mentioning a moral foundation across each manipulated moral foundation (e.g., harm frequencies when harm, fairness, ingroup, authority and purity were framed). All of these tests were significant (all F’s > 19.6, p’s < .001). Next we conducted within-samples t-tests examining whether the intended moral frame had the highest frequency (e.g., of harm-related words), compared to when the other moral foundations were manipulated for a particular participant. All of these tests were significant (all t’s > 3.44, p’s < .002). For example, harm-framed stances led participants to write a higher frequency of content that reflected the harm foundation (MHarm = 1.69%, SD = 2.13) compared to harm frequencies detected following the four other moral frames (fairness: MHarm = 1.21%, SD = 1.63; ingroup: MHarm = 1.18%, SD = 1.89; authority: MHarm = 0.64%, SD = 1.23; purity: MHarm = 0.82%, SD = 1.37). The same pattern was found for the fairness, ingroup, authority, and purity-framed stances on issues. Details of these tests can be found on the first author’s website. These analyses confirm that the moral foundation frames affected participants’ writing behavior as intended.

We also tested whether frequencies of the manipulated moral foundations in participants’ responses were related to their political attitude scores for each moral foundation. If this association existed, it would provide some insight into the processes of any attitude change. We found that following a harm-frame, the frequency of harm-related words in participants’ responses was unrelated to their harm political attitudes scores (r = .03, p = .58). We also found non-significant associations for fairness (r = -.07, p = .27), ingroup (r = -.06, p = .34), authority (r = -.07, p = .27), and purity (r = .02, p = .70). Thus, although the manipulated moral foundations were successfully detected in participants’ written responses, the degree that they were present was unrelated to final political attitudes.8

Discussion

Study 1 tested whether liberals’ and conservatives’ political attitudes were affected by exposure to moral frames of conservative stances on sociopolitical issues. The results provide preliminary support for our entrenching hypothesis. Exposure to issues framed with two of the moral foundations more relevant to conservatives (authority, purity), led conservatives to bolster their conservative attitudes relative to conservatives not initially exposed to moral frames. As the ingroup moral foundation tends to be more relevant for conservatives, one would expect similar results following exposure to this foundation; however, we did not observe this pattern. In this study we also did not find any support for the persuasion hypothesis. Liberals exposed to liberal-relevant moral frames (harm, fairness) on conservative stances on issues did not adopt relatively more conservative attitudes.

Study 1 provides initial evidence that relevant moral foundations can influence political attitudes for those with a more conservative orientation, in particular, leading to more entrenched conservative views. Study 1, however, tested only conservative pro-attitudinal stances on issues. To provide a complete test of our hypotheses, and to conceptually replicate our findings, we need to examine the effects of moral foundations on changing political attitudes for liberal pro-attitudinal stances on issues. Thus, we conducted Study 2 using the same general design as Study 1. The central change in Study 2 was to use moral foundations to frame stances grounded in liberal views (e.g., enhancement of social programs).

Study 2: Liberal Stances on Issues

Method

Participants

A sample of 713 American participants volunteered, using Mechanical Turk, as in Study 1. The study was completed by 627 participants (12.1% attrition rate), who were paid $1.25. Political orientation was as follows: 52.1% liberal, 14.8% moderate, 22.3% conservative, 5.7% libertarian, 3.2% do not know, 1.6% other, and 0.3% undisclosed. Our analyses included only those who identified along the liberal-conservative continuum. One participant was excluded for not following instructions, resulting in a final sample of 558 participants (57.0% women, Mage = 33.19, SD = 11.43). Ethnic groups included: 78.5% White, 7.3% Black, 4.5% Hispanic, 4.8% Asian, 1.1% Native American, 0.7% Middle Eastern, 2.5% Other, and 0.2% undisclosed. The sample was well-educated (e.g., 39.3% Some college/Associate degree, 36.6% Bachelor’s, 12.2% Master’s, 3.8% Professional/PhD) and reported to be almost average in subjective socioeconomic status, M = 5.02, SD = 1.76. The mean political orientation was slightly to the left of the mid-point on the liberal-conservative scale, M = 3.32, SD = 1.72.

Design and procedure

Study 2 aimed to examine how exposure to moral foundation frames of liberal pro-attitudinal stances affect political attitudes of liberals and conservatives. The design and procedure was the same as in Study 1. Our central manipulation was exposure to the moral foundation framing task either before (moral frame condition) or after (control condition) measurement of political attitudes. In the framing task, participants were exposed to the five moral frames and five political issues according to the five Latin Square conditions, as in Study 1. Participants were asked to write 2-3 points that supported 10 stances on issues (i.e., 2 stances per moral frame-issue combination). The primary change from Study 1 was that in Study 2 all of the stances were pro-attitudinal for liberals (as opposed to pro-attitudinal for conservatives). Participants completed the same political issues questionnaire and background questions as in Study 1.

Materials

The five moral foundations were used to reframe each of the five issues twice, resulting in 50 liberal stances. As in Study 1, a pilot test (N = 112) confirmed that the morally-framed stances significantly reflected the intended moral foundation across issues (all t’s > 2.2, p’s < .04). Political attitudes were measured using the 10-item political issues questionnaire. Political attitude scores on the liberally worded items were reverse-coded to create conservative-oriented index scores on each issue. Correlations between item-pairs had a median of r = .42 (range: r (552) = .37, p <.001 to r(554) = .59, p < .001).

Results

We created political-attitude scores for each moral foundation by following the same data preparation procedure as described in Study 1. Study 2 provided another opportunity to test our two main hypotheses concerning the effects of the five moral foundations on the political attitudes of liberals and conservatives. Given that the stances framed were liberal pro-attitudinal, the entrenching hypothesis predicts that liberals will bolster their political attitudes (i.e., endorse even less conservative attitudes), following exposure to stances framed by the liberal-relevant, harm and fairness moral foundations, as compared to liberals not first exposed to moral frames.

However, if moral foundations can induce even stronger effects, then we may find support for the persuasion hypothesis. Specifically, in addition to the effects expected by the entrenching hypothesis, this hypothesis predicts that conservatives may be persuaded to endorse more liberal views after exposure to liberal stances (i.e., which are counter-attitudinal for conservatives) that are framed with the language of the ingroup, authority, and purity moral foundations.

To test our entrenching and persuasion hypotheses, we conducted a MANOVA on the five moral-foundation political-attitude scores, testing for effects of the manipulation (moral frame vs. control) and political orientation, as in Study 1. This test indicated a main effect of political orientation, F(5,550) = 74.28, p < .001, ηp2 = .40, and of moral frame, F(5,550) = 5.09, p < .001, ηp2 = .04. The predicted multivariate interaction between frame and political orientation for the five moral foundation scores was also significant, F(5,554) = 2.62, p = .02, ηp2 = .02. As in Study 1, we followed up this result using multiple regressions for each of the five moral foundations (see Table 2 and Figure 2A-E).

Table 2.

Regressions of Conservative Attitudes Predicted by Moral Frame Exposure of Liberal Stances and Political Orientation, Study 2

| Step 1 | Harm

|

Fairness

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | t | b | SE | β | t | |||||

| Political Orientation | .26 | .02 | .44 | 11.67*** | .27 | .02 | .45 | 11.81*** | ||||

| Frame | -.11 | .08 | -.05 | -1.44 | -.21 | .08 | -.10 | -2.66** | ||||

| Constant | .07 | .11 | ||||||||||

| R2 | .200*** | .210*** | ||||||||||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Political Orientation | .22 | .03 | .37 | 7.42*** | .23 | .03 | .38 | 7.54*** | ||||

| Frame | -.11 | .08 | -.05 | -1.43 | -.21 | .08 | -.10 | -2.67** | ||||

| Political O. x Frame | .09 | .04 | .10 | 2.10* | .10 | .05 | .10 | 2.08* | ||||

| Constant | .07 | .12 | ||||||||||

| ΔR2 | .006* | .006* | ||||||||||

| Ingroup

|

Authority

|

Purity

|

||||||||||

| Step 1 | b | SE | β | t | b | SE | β | t | b | SE | β | t |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Political Orientation | .26 | .02 | .43 | 11.41*** | .25 | .02 | .44 | 11.84*** | .25 | .02 | .44 | 11.62*** |

| Frame | -.26 | .08 | -.13 | -3.32** | -.24 | .07 | -.12 | -3.28** | -.26 | .07 | -.13 | -3.54*** |

| Constant | .12 | .12 | .06 | |||||||||

| R2 | .205*** | .215*** | .212*** | |||||||||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Political Orientation | .28 | .03 | .47 | 9.34*** | .22 | .03 | .39 | 7.76*** | .23 | .03 | .41 | 8.22*** |

| Frame | -.26 | .08 | -.13 | -3.33** | -.24 | .07 | -.12 | -3.28** | -.26 | .07 | -.13 | -3.54*** |

| Political O. x Frame | -.05 | .04 | -.06 | -1.14 | .08 | .04 | .09 | 1.77 | .03 | .04 | .04 | 0.79 |

| Constant | .12 | .12 | .06 | |||||||||

| ΔR2 | .002 | .004 | .001 | |||||||||

Note:

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

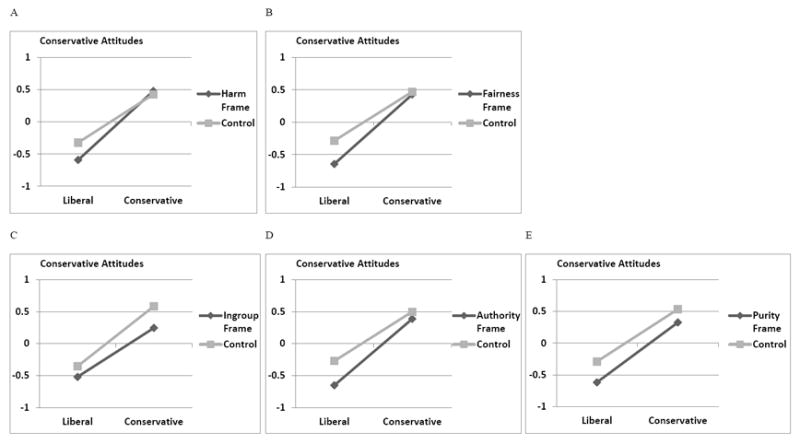

Figure 2.

Conservative attitudes by political orientation following exposure to liberal stances framed using the various moral foundations, Study 2. Liberal and conservative means are indicative of -/+ 1 SD of the mean political orientation, respectively. Moral foundations are graphed individually. A: Harm; B: Fairness; C: Ingroup; D: Authority; E: Purity.

For the harm moral foundation, results of the first step indicated a positive relation between political orientation and conservative attitudes, b = .26 (CI: .21, .30), p < .001, but no effect of the harm frame, b = -.11 (CI: -.26, .04), p = .15. The second step revealed that the interaction between political orientation and moral frame was significant, b = .09 (CI: .01, .18), p = .04 (see Figure 2A). We examined this interaction for those identifying as more liberal and more conservative (i.e., at -/+1 SD on political orientation). For those with a more liberal orientation, the harm frame decreased conservative attitudes (i.e., increased liberal attitudes), b = -.27 (CI: -.48, -.06), p = .01, relative to the control condition. There was no significant effect of the harm frame on political attitudes for those with a more conservative orientation, b = .05 (CI: -.16, .26), p = .64. We examined the fairness foundation and found a similar overall pattern (see Figure 2B). Specifically, political orientation predicted conservative attitudes, b = .27 (CI: .23, .32), p < .001. In addition, there were an effect of moral frame, b = -.21 (CI: -.37, -.06), p = .008, and on the second step, an overall interaction, b = .10 (CI: .01, .19), p = .04. Whereas liberals exposed to the fairness frame endorsed significantly lower conservative attitudes, b = -.38 (CI: -.60, -.16), p = .001, the political attitudes of conservatives did not significantly vary by condition, b = -.04 (CI: -.27, .18), p = .69. In sum, relevant moral frames of liberal pro-attitudinal stances increased liberals’ existing attitudes. Therefore, these results support the entrenching hypothesis, similar to the results for conservatives in Study 1.

Next, we examined the effects of the conservative-relevant ingroup, authority, and purity frames on political attitudes. We found similar results for these three moral foundations (see Figure 2C-E). For the ingroup foundation, political orientation predicted political attitudes, b = .26 (CI: .21, .30), p < .001. There was also a significant effect of the ingroup frame, b = -.26 (CI: -.41, -.10), p = .001. Compared to the control condition, this result indicated that conservatives and liberals both had lower conservative attitudes following exposure to the ingroup frame. The interaction between our ingroup manipulation and political orientation was not significant, b = -.05 (CI: -.14, .04), p = .26. The results for the authority foundation also revealed an effect of political orientation, b = .25 (CI: .21, .29), p < .001, and moral frame, b = -.24 (CI: -.38, -.10), p = .001. Relative to the control condition, the authority frame decreased conservative attitudes of both conservatives and liberals. The interaction term for the authority foundation was not significant, b = .08 (CI: -.01, .16), p = .08. Finally, for the purity foundation, we found that political orientation was generally associated with political attitudes, b = .25 (CI: .20, .29), p < .001. Independently, the moral frame led to lower conservative attitudes for both conservatives and liberals, as compared to the control condition, b = -.26 (CI: -.40, -.12), p < .001. The interaction was not significant, b = .04 (CI: -.05, .12), p = .43. Thus, the findings for the ingroup, authority, and purity foundations support the persuasion hypothesis, as conservative respondents adopted more liberal attitudes following exposure to these foundations. We did not hypothesize that liberals would also shift based on exposure to conservative moral foundations for liberal issues.

In secondary analyses we analyzed the 2,560 written responses in the experimental condition to examine whether the moral foundation frames influenced the content of participants’ responses, and whether the moral foundation content detected was related to participants’ political attitudes. We used the same LIWC program, procedures, and moral foundations dictionary, as in Study 1. First, we examined whether moral foundation frames led to higher moral foundation frequencies in participants’ responses compared to when each moral foundation was not used as a frame. We conducted repeated measures ANOVAs comparing the frequency of a particular participant mentioning the same moral foundation across each manipulated moral frame. All of these tests were significant (all F’s > 35.69, p’s < .001). Next, we conducted within-samples t-tests, examining whether each manipulated moral frame led to the highest frequency (all t’s > 6.11, p’s < .001). For example, these tests revealed that exposure to harm-framed arguments increased the written frequency of harm-related words (MHarm = 3.29%, SD = 2.61) as compared to harm frequencies following the four other moral frames (fairness: MHarm = 0.88%, SD = 1.36; ingroup: MHarm = 0.68%, SD = 1.34; authority: MHarm = 0.92%, SD = 1.72; purity: MHarm = 0.88%, SD = 1.56). We found the same pattern for each moral foundation. Much like in Study 1, the manipulated moral foundation frames in Study 2 increased the frequency of written moral language consistent with the moral frame.

We again tested whether the frequencies of written content consistent with the manipulated moral foundations could help explain political attitudes. For example, we found that the frequency of harm-related words in participants’ responses was unrelated to harm political attitudes scores (r = -.03, p = .62). Overall, we found a mixed pattern and mostly weak correlations across the moral foundations (fairness, r = .00, p = .97; ingroup, r = -.14, p = .02; authority, r = .02, p = .80;and purity, r = .18, p < .01). Thus, it does not appear that the presence of moral foundation language in participants’ written responses can readily explain attitudes changing.

Discussion

Consistent with Study 1, Study 2 most clearly supports the entrenching hypothesis. Specifically, after exposure to moral frames of harm and fairness for liberal stances on issues, liberals bolstered their liberal attitudes, compared to those not exposed to moral frames. Conservatives did not show an effect of framing for these same moral foundations. In contrast to Study 1, the results of Study 2 also somewhat support the persuasion hypothesis. Conservatives and liberals exposed to the ingroup, authority, and purity frames of liberal issues increased their liberal attitudes, compared to those not initially exposed to moral frames. That is, beyond what was expected in the persuasion hypotheses, not only did conservatives, but liberals also shifted their political attitudes in the liberal direction.

General Discussion

The present research sheds light on the conditions under which moral foundation frames (Graham et al., 2013; Haidt, & Graham, 2007) can affect people’s political attitudes. Two studies exposed liberals and conservatives to a variety of sociopolitical issues framed in terms of five moral foundations. In Study 1, the stances on issues were pro-attitudinal for conservatives (e.g., less economic regulation), whereas Study 2 examined the same topics, but pro-attitudinal stances for liberals (e.g., more economic regulation). Across studies, political attitudes changed depending on whether or not the issue stances were pro-attitudinal and—to some extent—whether the moral frames were relevant (harm and fairness for liberals; ingroup, authority, and purity for conservatives).

Both studies found consistent evidence in support of our entrenching hypothesis. That is, exposure to relevant moral frames of pro-attitudinal stances on issues led to more entrenched political attitudes as compared to participants not exposed to moral frames. In Study 1, conservatives who viewed and reflected on conservative stances (on the economy, education, immigration, etc.), framed by the authority and purity moral foundations, bolstered their conservative attitudes. Likewise, in Study 2, liberals exposed to liberal stances on the same issues, framed by the harm and fairness foundations, increased their liberal attitudes. Thus, these studies provide some evidence that relevant moral foundations can strengthen existing political attitudes.

We found mixed support for our persuasion hypothesis, that is, the possibility that moral foundations can persuade individuals to change their political attitudes when counter-attitudinal stances are framed using relevant moral foundations. In Study 1, when exposed to conservative stances on issues, relevant moral foundation frames did not convince liberals to hold more conservative attitudes. However, in Study 2, conservatives indicated relatively more liberal attitudes following exposure to conservative-relevant moral frames of liberal stances on issues. Therefore, we have preliminary evidence, for conservatives, that relevant moral frames may facilitate crossing the political divide. As liberals also increased their liberal attitudes on liberal stances in response to the three conservative moral frames in Study 2, additional research may help clarify these unexpected findings.

In addition to building on moral foundations theory (Graham et al., 2013; Haidt, 2012), the present studies also extend prior research on moral foundations and political attitude change. Specific to the issue of the environment, conservatives have been persuaded to adopt more liberal attitudes when exposed to the conservative-relevant purity frame (Feinberg & Willer, 2012). This finding is consistent with the pattern observed in Study 2. However, instead of the entrenching pattern found in both of our studies, in the past study liberals’ attitudes were not detected to change following exposure to a liberal-relevant harm frame (Feinberg & Willer, 2012). It is possible that these prior results were due to the specific issue selected, the content of the study materials, or the sample of liberal and conservative participants. The present research attempted to allay these concerns, in part, by examining multiple issues, using all five moral foundations, and including both liberal and conservative perspectives across two samples. Future research using the five moral foundations, different issues, and mixed methodology may further generalize the current pattern of effects.

Although the present research was designed to test the effects of moral foundations on political attitudes, we could speculate on the processes involved. In both studies, participants in the experimental condition were exposed to moral frames and generated supporting arguments for the liberal or conservative stances on issues. In terms of the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), moral foundations may be factors that change political attitudes through either the peripheral or central routes. Is it simply exposure to moral frames that affects attitude change, or is more careful deliberation of information necessary? First, consider exposure to pro-attitudinal stances on issues. In this context, people may not think carefully about a stance on an issue that is already congruent with their views (e.g., Kunda, 1990). Consistent with the peripheral route, it is therefore conceivable that exposure to subtle, moral foundation language may cue individuals’ moral intuitions, which may directly lead to more favorable (entrenched) attitudes. Because this pattern was found consistently for relevant moral frames, this suggests that this process may hinge on moral cues that “feel right” or seem important (e.g., Cesario et al., 2004; Graham et al., 2009). Alternatively, and more aligned with the central route, moral frames that are relevant may make issues seem more significant to individuals. This could lead to more thorough processing of the issues and may lead to more confidence in people’s thoughts on issues. Such greater confidence in pro-attitudinal thoughts could lead to more polarized attitudes (e.g., Petty, Briñol, & Tormala, 2002). Similar processes may occur when individuals are exposed to counter-attitudinal stances on issues. However, as people may be more motivated to defend their political beliefs in a counter-attitudinal context, it is conceivable that some type of central route processes may be necessary for moral frames to persuade political attitudes. In the present studies, we asked participants to write supporting arguments for the morally framed stances, but not their freely formed thoughts. Although we found that the moral frames affected the moral content of their supporting points, the degree of moral content did not explain final political attitudes. Thus, these analyses provide limited insight into the processes involved. For example, participants’ positive or negative thoughts about the issues may have differed from their written statements, which were instructed to be consistent with the stances on the issues. Thus, it would be informative if future research more directly tested whether processes that are peripheral or central (e.g., increased thought confidence) can help explain how relevant moral frames induce attitude change. Additional research could also examine whether political attitudes can be shifted through other persuasive means involving moral foundations. For example, prior research on persuasion has examined various peripheral cues (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Moral framing could also operate via alternative peripheral mediums, such as images that capture moral foundation meanings (Pizarro, Detweiler-Bedell, & Bloom, 2006).

The asymmetry of support for the persuasion hypothesis in Studies 1 and 2 between liberals and conservatives was not predicted. Emerging research, however, provides a possible explanation for this pattern of results. Contrary to lay beliefs and researchers’ predictions, recent studies have revealed that liberal ideology is more consistently (rigidly) held than conservative ideology (Kesebir, Philips, Anson, Pyszcznski, & Motyl, 2013). That is, across studies and political issues, liberals’ political beliefs show less variation and more consistent support for liberal stances on issues. However, conservatives’ opinions align with a range of political beliefs (i.e., greater within-person variability) on conservative as well as liberal viewpoints (Kesebir et al., 2013). This suggests that liberals may find it relatively easy to identify where they stand on morally framed issues, perhaps especially making conflicting views more apparent and less persuasive. Conservatives, however, may hold various degrees of support for different topics, potentially leading to persuasion in the direction of morally framed issues. More insight into this pattern may be garnered by conducting additional research on the consistency of the pattern of the present results and by testing the processes involved.

Limitations

The generalizability of the results of these studies is partly confined to our operationalizations of the moral foundations. In terms of specific moral foundations, across studies, the ingroup moral foundation showed inconsistent effects for those with a more conservative orientation. In both studies, we used references to America and Americans to frame the ingroup moral foundation. In Study 1, the authority and purity frames entrenched conservatives’ attitudes, but the ingroup frame did not. In Study 2, the ingroup frame persuaded conservatives (and also liberals) to adopt relatively more liberal attitudes. Given that the American ingroup may include many groups for participants in our samples, such references may be more useful for persuading conservatives to adopt typically non-conservative views, but less useful for entrenching conservative views. Instead, perhaps more proximal ingroup references may be more applicable, such as relating to one’s political party, family, or social class. These variations would still fit within the ingroup moral foundation, and would corroborate observations of some conservatives differentiating between various groups of U.S. citizens as “true” Americans or not (Frank, 2004). Future research could determine whether degree of ingroup closeness, or variations in the operationalizations of the other moral foundations, affects moral framing-related attitude change.

There are other limits on the generalizability of our findings. In both studies participants tended to be well educated and slightly below average in perceived socio-economic standing. They also volunteered to complete tasks related to current issues. Although controlling for a variety of background characteristics did not affect the results in either study, future research could study the effects of moral foundation-based frames using a variety of groups from different settings, including those that are more varied in education, socioeconomic status, and interest in current events.

We collected data from over one thousand participants in the present research. We aimed to have a similar number of participants in each study to facilitate the reliability of theoretical comparisons between studies. Our recruitment efforts resulted in approximately 560 participants in each study that identified along the liberal-conservative continuum. We believe that this number of participants provided us with adequate power to test for the effects of our manipulations in samples that varied in political orientation. Although we acknowledge that larger samples would increase the power to replicate our results (e.g., Perugini, Gallucci, & Constantini, 2014), we note that the relatively moderate sample sizes employed reduce the likelihood that our findings were minute effects that can sometimes be detected in very large sample sizes.

Implications

The present research contributes to the study of moral and political psychology by specifying some conditions in which moral foundations can affect political attitudes. Our strongest evidence across studies has implications when the relevant moral foundations are known (e.g., in an organization, team, political party, etc.). Capitalizing on this information may be useful for rallying support behind issues. For instance, in U.S. politics, perhaps the relative lack of moral framing led Democrats to lose in the 2004 federal election (Haidt, 2012), and was “a major reason” that Democrats lost the House of Representatives in the 2010 election (Lakoff & Wehling, 2012, p.32). We cannot confirm these assertions; however, the present research suggests that when addressing a liberal or conservative audience, on liberal or conservative stances, respectively, discussions framed using relevant moral foundations may embolden support. Consistent with the procedure of the present research, this may involve encouraging individuals to reflect on topics that are framed with relevant moral foundations. Although the present research focused on political issues, similar effects may be found in communities, groups, or workplaces, when presenting ideas broadly (e.g., social policy, marketing, health communication, etc.) that are framed in terms of relevant moral foundations. Future research could confirm these possibilities.

Conclusion

Prior research has established that liberals and conservatives differ in the moral foundations they find to be more relevant – harm and fairness for liberals, and ingroup, authority, and purity for conservatives (Graham et al., 2009). However, the extent that all five of these moral foundations facilitate broad changes in political attitudes was previously unclear. The present research demonstrated that the political attitudes of conservatives and liberals can be affected by exposure to moral foundations, in particular, when the moral foundations are relevant to the target audience. Although we conducted a broad test of the role of moral foundations in changing political attitudes, our examination was also relatively straightforward. Future research may benefit from testing the effects of complex combinations of moral foundations and applying the framework used in the present research across varied domains and settings.

Footnotes

We focus on the main five moral foundations as they are most relevant to the liberal-conservative dimension (Graham et al., 2009). Haidt and colleagues have proposed a possible sixth moral domain, which pertains to liberty and resistance of oppression. The liberty foundation has been found to help characterize libertarian moral roots (Iyer, Koleva, Graham, Ditto, & Haidt, 2012), which are not the focus of the present research.

These examples are paraphrased versions of the political items used in Graham et al. (2009). However, a variety of items have been used to assess moral foundations (see Graham et al., 2011).

We acknowledge that the strength of the relationships among particular political topics and political ideology may vary over time and societal conditions.

In both studies over 95% of participants indicated that they were U.S. citizens and over 93% were born in America.

All materials and design information for both studies can be accessed in the online Methodology Appendix.

Prior to including political orientation as a predictor, we examined whether our manipulation of moral framing had an overall effect on political orientation scores. These tests were not significant in Study 1, F(1, 567) = 1.83, p = .18, or Study 2, F(1, 556) = 0.18, p = .67.

Although results are reported without controlling for demographic variables, the main findings of Studies 1 and 2 remain significant when controlling for age, gender, level of education, and subjective socioeconomic status.

We also examined whether political orientation was related to higher frequencies of moral foundation content following moral frame exposure. For both studies, none of these correlations exceeded r = |.09|, and none were significant. Moreover, we examined whether participants’ overall effort (i.e., total words written during the framing tasks) was related to political orientation, and whether this factor could account for changes in political attitudes. Correlations between word count and political orientation for the moral foundations were mostly nonsignificant and never exceeded r = |.15| in either study. We also did not observe any consistent patterns for correlations between words written and measured political attitudes across studies, and controlling for words written did not affect the results. Regardless of political orientation, study participants followed the directions of the moral framing task relatively uniformly.

This is the final peer-reviewed version of this manuscript pending final revisions at Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

Contributor Information

Martin V. Day, Princeton University

Susan T. Fiske, Princeton University

Emily L. Downing, Microsoft

Thomas E. Trail, RAND Corporation

References

- Bartels LM. Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior. 2002;24:117–150. [Google Scholar]

- Bobocel DR, Son Hing LS, Davey LM, Stanley DJ, Zanna MP. Justice-based opposition to social policies: Is it genuine? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:653–669. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Dweck CS, Ross L, Kay AC, Mislavsky NO. Political mindset: Effects of scheme priming on liberal-conservative positions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45:890–895. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s mechanical turk: A new source of inexpensive yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesario J, Grant H, Higgins ET. Regulatory fit and persuasion: Transfer from “feeling right”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:388–404. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB. Influence: Science and practice. New York: Pearson; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Clark JK, Wegener DT, Fabrigar LR. Attitudinal ambivalence and message-based persuasion: Motivated processing of proattitudinal information and avoidance of counterattitudinal information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008a;34:565–577. doi: 10.1177/0146167207312527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JK, Wegener DT, Fabrigar LR. Attitudinal accessibility and message processing: The moderating role of message position. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008b;44:354–361. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GL. Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:808–822. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JT, Pilanski JM. Political intolerance, right and left. Political Psychology 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Ditto PH, Lopez DF. Motivated skepticism: Use of differential decision criteria for preferred and nonpreferred conclusions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:568–584. [Google Scholar]

- Emler N. Morality and political orientations: An analysis of their relationship. European Review of Social Psychology. 2002;13:259–291. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg M, Willer R. The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychological Science. 2012;24:56–62. doi: 10.1177/0956797612449177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske AP. Structures of social life: The four elementary forms of human relations: Communal sharing, authority ranking, equality matching, market pricing. New York: Free Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Frank T. What’s the matter with Kansas? How conservatives won the heart of America. New York: Henry Holt and Co; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Haidt J, Nosek BA. Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:1029–1046. doi: 10.1037/a0015141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Haidt J, Koleva S, Motyl M, Iyer R, Wojcik SP, Ditto PH. Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2013;47:55–130. [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Nosek BA, Haidt J, Iyer R, Koleva S, Ditto PH. Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:366–385. doi: 10.1037/a0021847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J. The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;108:814–834. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.4.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J. The new synthesis in moral psychology. Science. 2007;316:998–1002. doi: 10.1126/science.1137651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J. The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. New York: Random House; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J, Graham J. When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research. 2007;20:98–116. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J, Joseph C. Intuitive ethics: How innately prepared intuitions generate culturally variable virtues. Daedalus. 2004:55–66. Special issue on human nature. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J, Joseph C. The moral mind: How five sets of innate intuitions guide the development of many culture-specific virtues, and perhaps even modules. In: Carruthers P, Laurence S, Stich S, editors. The innate mind. Vol. 3. New York: Oxford; 2007. pp. 367–391. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer R, Koleva S, Graham J, Ditto P, Haidt J. Understanding libertarian morality: The psychological dispositions of self-identified libertarians. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:1–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby WG. Ideological identification and issue attitudes. American Journal of. Political Science. 1991;35:178–205. [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT. The end of the end of ideology. American Psychologist. 2006;61:651–670. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT, Amodio DM. Political ideology as motivated social cognition: Behavioral and neuroscientific evidence. Motivation and Emotion. 2012;36:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kesebir P, Phillips E, Anson J, Pyszczynski T, Motyl M. Ideological consistency across the political spectrum: Liberals are more consistent but conservatives become more consistent when coping with existential threat. 2013 Available at SSRN: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2215306.

- Kohlberg L. Stage and sequence: The cognitive-developmental approach to socialization. In: Goslin DA, editor. Handbook of socialization theory and research. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1969. pp. 347–480. [Google Scholar]

- Koleva SP, Graham J, Iyer R, Ditto PH, Haidt J. Tracing the threads: How five moral concerns (especially purity) help explain culture war attitudes. Journal of Research in Personality. 2012;46:184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kunda Z. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:480–498. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff G. Moral politics: How liberals and conservatives think. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff G, Wehling E. The little blue book: The essential guide to thinking and talking democratic. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Landau MJ, Soloman S, Greenberg J, Cohen F, Pyszcynski T, Arndt J, Cook A, et al. Deliver us from evil: The effects of mortality salience and reminders of 9/11 on support for president George W. Bush. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:1136–1150. doi: 10.1177/0146167204267988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AY, Aaker JL. Bringing the frame into focus: The influence of regulatory fit on processing fluency and persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:205–218. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord CG, Ross L, Lepper MR. Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:2098–2109. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz EM, Shariff AF. Climate change and moral judgment. Nature. Climate Change. 2012;2:243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Mercier H, Sperber D. Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2011;34:57–111. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X10000968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro GD, Zirpoli J, Schuman A, Taulbee J. Third-party labels bias evaluations of political platforms and candidates. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2013;35:151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:673–693. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer DM, Trail TE. Why leaning to the left makes you lean to the left: Effect of spatial orientation on political attitudes. Social Cognition. 2010;28:651–661. [Google Scholar]

- Paolacci G, Chandler J. Inside the turk: Understanding mechanical turk as a participant pool. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23:184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Booth RJ, Francis ME. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count: LIWC2007. Austin: LIWC.net; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Perugini M, Gallucci M, Costantini G. Safeguard power as a protection against imprecise power estimates. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2014;9:319–332. doi: 10.1177/1745691614528519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Briñol P, Tormala ZL. Thought confidence as a determinant of persuasion: The self-validation hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:722–741. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.5.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. Issue involvement can increase or decrease persuasion by enhancing message-relevant cognitive responses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:1915–1926. [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In: Zanna P, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 19. New York: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 123–204. [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Wegener DT. The elaboration likelihood model: Current status and controversies. In: Chaiken S, Trope Y, editors. Dual process theories in social psychology. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro DA, Detweiler-Bedell B, Bloom P. The creativity of everyday moral reasoning: Empathy, disgust, and moral persuasion. In: Kaufman JC, Baer J, editors. Creativity and reason in cognitive development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz EM, Chaiken S, Tordesillas RS. Attitude strength and resistance processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:408–419. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redlawsk DP. Hot cognition or cool consideration? Testing the effects of motivated reasoning on political decision making. The Journal of Politics. 2002;64:1021–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SH. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 25. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1992. pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Shweder RA, Mahapatra M, Miller J. Culture and moral development. In: Kagan J, Lamb S, editors. The emergence of morality in young children. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1987. pp. 1–83. [Google Scholar]

- Skitka LJ. Do the means always justify the ends, or do the ends sometimes justify the means? A value protection model of justice reasoning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:588–597. [Google Scholar]

- Skitka LJ, Bauman CW. Moral conviction and political engagement. Political Psychology. 2008;29:29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Taber CS, Lodge M. Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science. 2006;50:755–769. [Google Scholar]

- Tesser A, Conlee MC. Some effects of time and thought on attitude polarization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1975;31:262–270. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The development of social knowledge: Morality and convention. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]