Abstract

Background and objectives

Despite the potential benefits of conservative management, providers rarely discuss it as a viable treatment option for patients with advanced CKD. This survey was to describe the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of nephrologists and primary care providers regarding conservative management for patients with advanced CKD in the United States.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We developed a questionnaire on the basis of a literature review to include items assessing knowledge, attitudes, and self-reported practices of conservative management for patients with advanced CKD. Potential participants were identified using the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile. We then conducted a web-based survey between April and May of 2015.

Results

In total, 431 (67.6% nephrologists and 32.4% primary care providers) providers completed the survey for a crude response rate of 2.7%. The respondents were generally white, men, and in their 30s and 40s. Most primary care provider (83.5%) and nephrology (78.2%) respondents reported that they were likely to discuss conservative management with their older patients with advanced CKD. Self-reported number of patients managed conservatively was >11 patients for 30.6% of nephrologists and 49.2% of primary care providers. Nephrologists were more likely to endorse difficulty determining whether a patient with CKD would benefit from conservative management (52.8% versus 36.2% of primary care providers), whereas primary care providers were more likely to endorse limited information on effectiveness (49.6% versus 24.5% of nephrologists) and difficulty determining eligibility for conservative management (42.5% versus 14.3% of nephrologists). There were also significant differences in knowledge between the groups, with primary care providers reporting more uncertainty about relative survival rates with conservative management compared with different patient groups.

Conclusions

Both nephrologists and primary care providers reported being comfortable with discussing conservative management with their patients. However, both provider groups identified lack of United States data on outcomes of conservative management and characteristics of patients who would benefit from conservative management as barriers to recommending conservative management in practice.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease; geriatric nephrology; quality of life; hemodialysis; survival; attitude; humans; knowledge; renal insufficiency, chronic; surveys and questionnaires

Introduction

Conservative management (CM) is gaining gradual recognition as a treatment alternative to dialysis and transplant in the United States. The recent Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference on Supportive Care in CKD advocated for CM as a priority to improve patient-centered care (1), and the Renal Physician Association (RPA) has provided recommendations emphasizing discussions of prognosis and offering the option of CM (2). However, the lack of a precise definition of CM has limited the dissemination of CM (3). To address this concern, comprehensive CM was defined by the KDIGO Controversies Conference on Supportive Care in CKD as “planned holistic patient-centered care for patients with glomerular filtration rate category (G) 5 CKD that includes interventions to delay progression of kidney disease and minimize risk of adverse events or complications, shared decision making, active symptom management, detailed communication including advance care planning, psychologic support, social and family support, and cultural and spiritual domains of care.” Although dialysis is likely to offer healthier, more functional patients a significant survival benefit (regardless of age), studies have shown that CM may provide similar survival and quality of life in older patients with high comorbidity burdens (4–10). These studies suggest that some patients with advanced comorbidities and poor functional status may be better managed with CM than via dialysis (11). However, it is not clear that CM is adequately discussed as a viable treatment option in the United States (12,13). Reasons for this may include providers’ uncertainty about patient prognosis, a relative lack of evidence of its efficacy compared with dialysis, and providers’ personal values, which may prioritize survival over quality of life (14–16).

Although several survey studies have described nephrologists’ attitudes on withholding or withdrawing dialysis (16–19), there are no data on providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices surrounding CM in the United States. Furthermore, a large number of patients with CKD is managed solely by their primary care providers (PCPs) (20–23), on whom little data regarding CM exists. Because of differences in training and experience, we hypothesized that PCPs and nephrologists may show important differences in knowledge, attitudes, and practices of CM. Therefore, we sought to describe nephrologists’ and PCPs’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices of CM for patients with advanced CKD in the United States and assess whether the two physician groups differ in those domains.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sample

We conducted a web-based survey from April to May of 2015 using the SurveyMonkey platform. We used the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile (24) to identify nephrologists and PCPs who were actively practicing in the United States. We invited a simple random sample of 16,193 providers by email (stratified by nephrology and PCP).

Survey Design and Content

We developed survey items on the basis of a literature review (4–6,12–16,25–28) to include items assessing knowledge, attitudes, and self-reported practices regarding CM for patients with advanced CKD. The items were modified after review by three investigators with content expertise on the subject matter as well as survey experts. The questionnaire was then pilot tested with six nephrologists and refined to improve clarity. The questionnaire was pilot tested again with 13 trainees in nephrology and internal medicine. The final survey comprised 33 items that addressed physician practices, attitudes, knowledge, and demographics and took 10 minutes to complete.

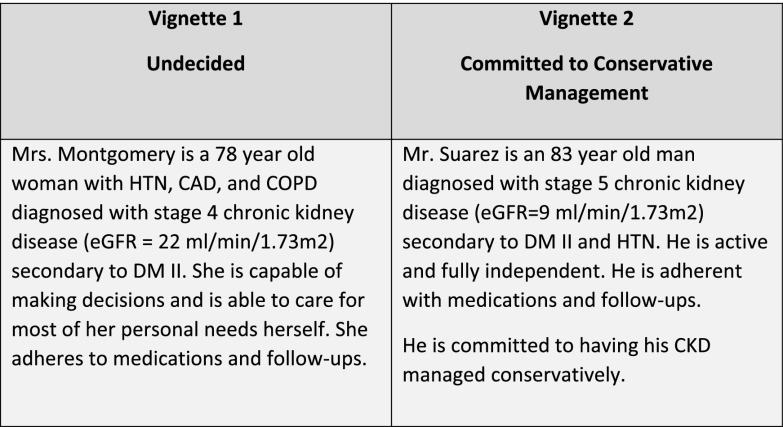

To query physician practices, we presented two vignettes that represented common patient scenarios (shown in Figure 1) and self–reported practice questions (Supplemental Appendix). The first vignette presented an undecided 78-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and stage 4 CKD. The patient was independent in physical functioning and decision making. To better understand measures used by PCPs and nephrologists to treat a patient committed to CM, a second vignette presented a patient committed to use CM. The second vignette presented an independent 83-year-old man with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and nondialysis–dependent stage 5 CKD. This patient was committed to CM after previous discussions of treatment options. For the first of these vignettes describing the undecided patient, respondents were asked to rate how likely they would be to discuss treatment options, such as dialysis or CM, using a five–point Likert scale (ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree), and for both vignettes, they were asked to endorse medications or management approaches (e.g., angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEis] and pain management) that they would likely prescribe to the patient. Providers were also asked about the number of patients with CKD that they were currently managing with CM and how likely they were to discuss CM with their patients with nondialysis-dependent CKD and their patients who recently initiated dialysis and were not showing clinical improvement.

Figure 1.

Description of clinical vignettes. CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM II, type 2 diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension.

To assess provider attitudes, we asked respondents to rate their level of agreement (strongly agree to strongly disagree) on each of eight potential barriers, including time constraints, fear of patient’s negative reaction, valuing survival over quality of life, uncertainty about the effectiveness of CM, and uncertainty in patient eligibility and patient selection.

To assess provider knowledge, we asked a series of questions that addressed outcomes of CM versus dialysis. We also asked about the RPA guideline recommendations regarding CM. The complete survey is available online (Supplemental Appendix).

Survey Implementation

An initial broadcast email was sent to each recipient on day 0. Two additional reminder emails were broadcast to each recipient on days 14 and 22. The emails were personally addressed to each recipient and included study background, the expected length of time needed to complete the survey, a link to the web-based survey, a statement of confidentiality, and an offer for a $25 electronic gift card at completion. All of the emails had the same content with the exception of the third email, which also included a 1-week deadline for completion. These survey implementation strategies are in accordance with best practices to improve the response rate to electronic surveys (29). The email open rate and survey link open rate were provided by Redi-Data, Inc., which managed the deployment of the emails. This study was approved by the University of New Mexico Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analyses

Responses were summarized using descriptive statistics. Differences between nephrologists and PCPs were compared using chi-squared or Fisher exact tests as appropriate. Logistic regression approaches were used to compare responses from physician groups while controlling for demographic factors of the survey respondents. We aimed to recruit a total of 400 respondents, with approximately equal numbers of nephrologists and PCPs, to have 80% power to detect differences that were moderate in size: odds ratios (ORs) of ≥1.8 and standardized effect sizes of ≥0.30. Two–sided P values were reported for all comparisons, and P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using the R statistical package.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Emails were sent to 16,193 providers. Of these, 595 did not have functioning email addresses, 191 unsubscribed from the email, and 4502 opened the invitation email. In total, 431 physicians ultimately completed the survey for a crude response rate of 2.7%. The respondents were predominantly white, men, and in their 30s and 40s (Table 1), and almost two thirds were nephrologists. Nephrologists and PCPs differed significantly in age, type of practice, and number of patients with CKD seen in the past week. Nearly 50% of nephrology and PCP respondents were in private practice (i.e., solo practitioner, private group, or multispecialty group).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the responding health care providers

| Participant Characteristics | N (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total,a n=431 | Primary Care Providers, n=127 | Nephrologists, n=265 | ||

| Women | 120 (30.5) | 42 (33.1) | 77 (29.3) | 0.58 |

| Age, yr | ||||

| 20–29 | 11 (2.8) | 9 (7.1) | 2 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| 30–39 | 121 (30.7) | 41 (32.3) | 78 (29.7) | |

| 40–49 | 108 (27.4) | 25 (19.7) | 81 (30.8) | |

| 50–59 | 89 (22.6) | 38 (29.9) | 51 (19.4) | |

| 60–69 | 55 (14.0) | 13 (10.2) | 42 (16.0) | |

| ≥70 | 10 (2.5) | 1 (1.0) | 9 (3.4) | |

| Ethnicityb | ||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 129 (29.9) | 40 (31.5) | 87 (32.8) | 0.26 |

| Black | 15 (3.5) | 7 (5.5) | 8 (3.0) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 16 (3.7) | 2 (1.6) | 14 (5.3) | |

| White | 218 (50.6) | 68 (53.5) | 149 (56.2) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 21 (4.9) | 10 (7.8) | 10 (3.8) | |

| Years since medical school | ||||

| 0–5 | 101 (25.7) | 35 (28.0) | 66 (24.9) | 0.13 |

| 6–10 | 64 (16.3) | 17 (13.6) | 46 (17.4) | |

| 11–15 | 66 (16.8) | 14 (11.2) | 50 (18.9) | |

| 16–20 | 45 (11.5) | 21 (16.8) | 24 (9.1) | |

| 21–25 | 43 (10.9) | 14 (11.2) | 29 (10.9) | |

| ≥26 | 74 (18.8) | 24 (19.2) | 50 (18.9) | |

| Practice organization | ||||

| Academic | 126 (32.0) | 24 (19.0) | 102 (38.5) | <0.001 |

| Government facility based | 24 (6.1) | 8 (6.3) | 15 (5.7) | |

| Hospital based | 54 (13.7) | 35 (27.8) | 17 (6.4) | |

| Multispecialty | 44 (11.2) | 20 (15.9) | 24 (9.1) | |

| Private group | 117 (29.7) | 27 (21.4) | 90 (34.0) | |

| Solo | 29 (7.4) | 12 (9.5) | 17 (6.4) | |

| No. of patients with CKD/ESRD seen in last 1 wk | ||||

| 0–15 | 141 (36.0) | 93 (73.2) | 45 (17.2) | <0.001 |

| 16–30 | 69 (17.6) | 27 (21.3) | 42 (16.0) | |

| 31–45 | 52 (13.3) | 5 (3.9) | 47 (17.9) | |

| 46–60 | 41 (10.5) | 1 (0.8) | 40 (15.3) | |

| >60 | 89 (22.7) | 1 (0.8) | 88 (33.6) | |

| No. of patients with CKD being managed conservatively | ||||

| 0 | 25 (6.1) | 9 (7.1) | 14 (5.3) | 0.001 |

| 1–2 | 53 (13.0) | 18 (14.3) | 33 (12.4) | |

| 3–4 | 88 (21.6) | 22 (17.5) | 66 (24.9) | |

| 5–10 | 90 (22.1) | 15 (11.9) | 71 (26.8) | |

| >10 | 152 (37.3) | 62 (49.2) | 81 (30.6) | |

In total, 23 did not provide a response for the number of patients with CKD managed conservatively; 37 did not provide responses for women, age, and practice organization; 38 did not provide responses for years since medical school; and 39 did not provide responses for number of patients with CKD/ESRD seen or nephrologist/primary care provider status.

One nephrologist recorded ethnicity as both Asian or Pacific Islander and white, and two nephrologists recorded ethnicity as both Hispanic or Latino and white.

Practices

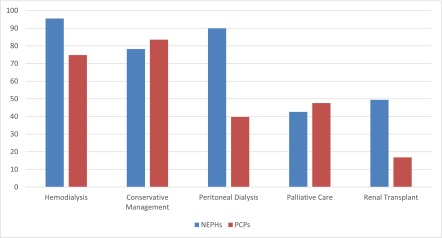

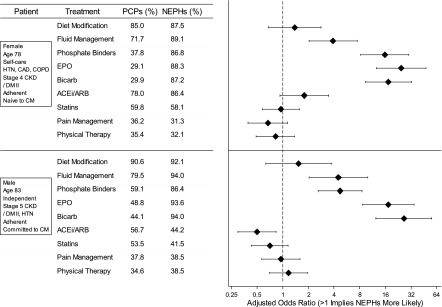

For the undecided patient described in the first vignette, a 78-year-old woman with multiple comorbidities, functional independence, and advanced CKD, both nephrologists and PCPs were likely to discuss hemodialysis (95.5% of nephrologists versus 74.8% of PCPs) and CM (78.2% of nephrologists versus 83.5% of PCPs) as treatment options (Figure 2), with nephrologists being significantly more likely to discuss hemodialysis (P<0.001). Nephrologists were also more likely (P<0.001) to discuss peritoneal dialysis (89.9%) and renal transplant (49.4%) than PCPs (39.7% and 16.8%, respectively). Fewer than one half of nephrologists (42.6%) and PCPs (47.6%) were likely to discuss palliative care (Figure 2). With respect to medications and management that physicians would consider for the two patients (Figure 3), diet modification and fluid management were endorsed by at least 70% of both nephrologists and PCPs, whereas pain management and physical therapy were endorsed by <40% of each respondent group for either patient. Nephrologists were significantly more likely to prescribe bicarbonate, erythropoietin, active fluid management, and phosphate binders than PCPs (P≤0.001) to both patients. Overall, physicians were unlikely to prescribe pain management or physical therapy to either of the patients.

Figure 2.

Percentages of responding physicians who declared that they are likely or extremely likely to discuss each of the following management options in their practice with the undecided patient described in vignette 1. NEPH, nephrologist; PCP, primary care provider.

Figure 3.

Treatments that providers would consider for patients presented to them in the two survey vignettes. ACEi/ARB, angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; Bicarb, bicarbonate; CAD, coronary artery disease; CM, conservative management; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM II, type 2 diabetes mellitus; EPO, erythropoietin; HTN, hypertension; NEPH, nephrologist; PCP, primary care provider.

When comparing practice recommendations between the two patients, physicians were significantly more likely to prescribe pain management for the patient committed to CM in the second vignette (37.6% versus 32.7%; P=0.02). Nephrologists were somewhat more likely to consider physical/occupational therapy for the patient committed to CM in the second vignette (38.5% versus 32.1%; P=0.01), whereas PCPs were consistent in their recommendation of physical/occupational therapy between the two vignettes (34.6% versus 35.4%; P=0.85). Nephrologists were more likely than PCPs to recommend the same prescriptions between the two vignettes, with the exception of ACEis. After accounting for physician characteristics, nephrologists were significantly more likely to recommend phosphate binders (OR, 2.97; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.24 to 7.08; P=0.01) and Erythropoieitin (OR, 8.97; 95% CI, 3.02 to 26.7; P<0.001) to the patient committed to CM than PCPs, whereas they were significantly less likely to prescribe ACEis (OR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.20 to 0.84; P=0.01) to that patient.

Nephrologists and PCPs reported similar practices in their approach to discussing CM as a treatment option for patients who were nondialysis dependent and nearing stage 5 CKD and patients who were not improving on dialysis after recent dialysis initiation; 61% of nephrologists reported discussing CM as a treatment option always or very often with their patients not on dialysis who were nearing stage 5 CKD, whereas 54.3% of PCPs reported the same practice (P=0.17). Both groups were less likely to discuss CM with patients not improving on dialysis (47.3% of nephrologists and 41.5% of PCPs; P=0.36). Despite some similarities in willingness to discuss CM as a treatment option, there were differences in the numbers of patients with CKD actually managed with CM between groups; nephrologists reported higher numbers overall (P=0.001). Regardless of the number of patients with CKD typically seen in a given week, PCPs were more likely to report that they were managing ≥11 patients with CKD with CM (46.5%, 53.8%, and 71.4% of those seeing 0–15, 16–30, or ≥30 patients with CKD in the past week, respectively; Ptrend=0.28), whereas nephrologists were more likely to report that they were managing ≥11 patients with CKD with CM if they had seen ≥60 patients with CKD in the past week (13.3%, 11.9%, and 40.0% of those seeing 0–15, 16–30, or ≥30 patients with CKD, respectively; Ptrend<0.001).

Attitudes

Overall, respondents reported that a discussion about CM with their patients with CKD was not difficult to initiate or time consuming and that they were not concerned about how their patients would respond if they initiated such a discussion (Table 2). Fewer nephrologists (14.3%) than PCPs (42.5%) endorsed difficulty in determining eligibility for CM (P<0.001) and limited information about its effectiveness as barriers (24.5% of nephrologists and 49.6% of PCPs; P<0.001). Conversely, nephrologists were more likely to endorse difficulty in determining whether a patient with CKD would benefit from CM (52.8%) than PCPs (36.2%; P=0.003).

Table 2.

Percentages of responding physicians who declared that they agree or strongly agree with statements suggesting that they do not discuss conservative management with their patients with CKD for the following reasons

| Barriers to Discussing Conservative Management | Nephrologists, N (%) | Primary Care Providers, N (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difficult to decide which patients benefit | 96 (52.8) | 67 (36.2) | 0.003 |

| Limited information about effectiveness | 65 (24.5) | 63 (49.6) | <0.001 |

| Too time consuming | 80 (30.3) | 37 (29.4) | 0.43 |

| Uncertainty about eligibility | 38 (14.3) | 38 (42.5) | <0.001 |

| Fear patient response | 40 (15.2) | 25 (19.8) | 0.62 |

| Difficult to initiate a discussion | 36 (13.6) | 20 (15.9) | 0.86 |

| Doubt patient capacity | 21 (8.0) | 12 (9.4) | 0.64 |

| Value survival over quality of life | 18 (6.8) | 9 (7.1) | 0.94 |

Knowledge

Almost all respondents endorsed statements that CM includes symptom management and advanced care planning and that CM is used for patients who forego dialysis (Table 3). Similarly, almost all disagreed that CM is used for patients who recently started dialysis or that it is the same as end of life care. More than one half of all respondents disagreed that CM is the same as palliative care of CKD. Nephrologists were less likely to agree that CM is used as a bridge to kidney transplantation (18.1%) than PCPs (30.7%; P<0.01) and more likely to agree that CM is used for patients who forego dialysis (86.4%) than PCPs (76.4%; P<0.01).

Table 3.

Percentages of responding physicians who agreed that, to the best of their knowledge, conservative management of CKD includes the following information

| Knowledge of Conservative Management | Nephrologists, N (%) | Primary Care Providers, N (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Includes symptom management | 259 (97.7) | 123 (97.0) | 0.42 |

| Includes advanced care planning | 250 (94.3) | 115 (90.6) | 0.52 |

| Is used for patients who forego dialysis | 229 (86.4) | 97 (76.4) | <0.01 |

| Is the same as palliative care of CKD | 117 (44.2) | 54 (42.5) | 0.98 |

| Is used as a bridge to kidney transplantation | 48 (18.1) | 39 (30.7) | <0.01 |

| Is the same as end of life care | 53 (20.0) | 14 (11.0) | 0.08 |

| Is used for patients who recently started dialysis | 31 (11.7) | 24 (18.9) | 0.14 |

In general, nephrologists and PCPs differed in their responses to items about outcomes of CM and dialysis (Table 4). Notably, significantly more PCPs were unsure about all of these questions nephrologists (P≤0.01), except the item declaring that CM and dialysis have a comparable number of hospital-free days in elderly patients (P=0.09). More nephrologists than PCPs identified that CM differs in survival from that in patients on dialysis with coronary artery disease (45.0% versus 22.4%; P<0.01) and that CM and dialysis do not have comparable outcomes for patients <75 years of age (80.3% versus 37.3%; P<0.001). Nephrologists were significantly more likely than PCPs to correctly identify each of the RPA guidelines regarding withdrawal or withholding of dialysis (from 64.0% to 94.3% versus from 27.6% to 87.4%, respectively; P≤0.04), except for the guideline that CM is recommended for patients with terminal illness from nonrenal causes (75.1% versus 73.2%; P=0.07) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentages of responding physicians who agreed that, to the best of their knowledge, the following accurately reflected information about conservative management of CKD

| Conservative management outcomes and guidelines | Nephrologists, N (%) | Primary Care Providers, N (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparisons with other treatments or conditions | ||||

| Both have comparable survival rates in nonelderly patients (<75 yr old) | ||||

| True | 14 (5.3) | 16 (12.7) | <0.001 | |

| False | 212 (80.3) | 47 (37.3) | ||

| Not sure | 38 (14.4) | 63 (50.0) | ||

| Both have comparable survival rates in elderly patients (>75 yr old) | ||||

| True | 163 (62.0) | 63 (50.0) | <0.001 | |

| False | 61 (23.2) | 14 (11.1) | ||

| Not sure | 39 (14.8) | 49 (38.9) | ||

| Both have comparable survival rates in patients with no other chronic health conditions | ||||

| True | 24 (9.1) | 31 (24.6) | <0.001 | |

| False | 188 (71.5) | 36 (28.6) | ||

| Not sure | 51 (19.4) | 59 (46.8) | ||

| Both have comparable survival rates in patients with coronary artery disease | ||||

| True | 58 (22.1) | 28 (22.4) | <0.001 | |

| False | 118 (45.0) | 28 (22.4) | ||

| Not sure | 86 (32.8) | 69 (55.2) | ||

| Both have a comparable number of hospital-free days in elderly patients (>75 yr old) | ||||

| True | 90 (34.0) | 31 (24.6) | 0.02 | |

| False | 105 (39.6) | 41 (32.5) | ||

| Not sure | 70 (26.4) | 54 (42.9) | ||

| Conservative management is recommended by guidelines for | ||||

| Patients with decision-making capacity who choose conservative management | ||||

| True | 250 (94.3) | 111 (87.4) | 0.03 | |

| False | 5 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Not sure | 10 (3.8) | 16 (12.6) | ||

| Patients who no longer have decision-making capacity and have previously refused dialysis | ||||

| True | 239 (90.2) | 96 (75.6) | 0.001 | |

| False | 10 (3.8) | 12 (9.4) | ||

| Not sure | 16 (6.0) | 19 (15.0) | ||

| Patients too unstable or uncooperative to undergo dialysis | ||||

| True | 232 (87.9) | 102 (81.0) | 0.04 | |

| False | 10 (3.8) | 3 (2.4) | ||

| Not sure | 22 (8.3) | 21 (16.7) | ||

| Patients with stage 5 CKD age >75 yr old | ||||

| True | 55 (20.8) | 47 (37.0) | <0.001 | |

| False | 169 (64.0) | 35 (27.6) | ||

| Not sure | 40 (15.2) | 45 (35.4) | ||

| Patients with terminal illness from nonrenal causes | ||||

| True | 199 (75.1) | 93 (73.2) | 0.07 | |

| False | 34 (12.8) | 8 (6.3) | ||

| Not sure | 32 (12.1) | 26 (20.5) | ||

| Patients who have significantly impaired functional status | ||||

| True | 181 (68.6) | 67 (52.8) | 0.01 | |

| False | 36 (13.6) | 19 (15.0) | ||

| Not sure | 47 (17.8) | 41 (32.3) | ||

Discussion

In this national survey, a majority of PCP and nephrologist respondents reported that they were likely to discuss CM with their older patients with advanced CKD. However, there were significant differences between provider groups in barriers to discussing CM and knowledge of CM; PCPs were more likely to endorse uncertainty about the effect of CM on survival as a barrier.

We found that nephrologists and PCPs were both likely to recommend CM as an option to an older patient with stage 4 CKD and several serious comorbidities. However, nephrologists were more likely to also recommend peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. PCPs remained neutral about peritoneal dialysis, perhaps because of unfamiliarity (i.e., 7% of the maintenance dialysis population) (30). Only about one third of both groups of providers recommended pain management and physical/occupational therapy for either hypothetical patient. This may reflect findings from studies that suggest that pain is an underappreciated symptom in patients with advanced CKD (31,32) and suggests that providers may not be well aware of the common decrements in physical function in advanced CKD (33). Alternative explanations to the low rate of addressing pain may be the concern of addiction from opiates, the belief that the treatment of pain falls in the domain of another practitioner, and the regulations of pain medications in certain locales. Another explanation for relatively low rate of addressing pain would be the lack of detailed information describing pain presented in the vignettes. Because these symptoms are among the most commonly reported in this population, recognizing and treating them early are clinically salient areas of intervention (31,32).

The majority of nephrologists and PCPs would prescribe ACEi/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), dietary modifications, and statins to the hypothetical patients described, but a significantly greater percentage of nephrologists would also prescribe bicarbonate, erythropoietin, and phosphate binders, reflecting that these are specialized management options. This trend held true even when a patient had already committed to CM. Nephrologists were more likely than PCPs to prescribe these treatments to a patient on CM. The physician groups differed in prescribing of ACEi/ARB; more nephrologists would prescribe ACEi/ARB to the patient with stage 4 CKD (eGFR=22 ml/min per 1.73 m2) than to the patient with stage 5 CKD (eGFR=9 ml/min per 1.73 m2). We can account for this difference, because treatment goals for stage 5 CKD are different from those of stages 3 and 4 CKD; that is, CM for the former is focused more on limiting uremic symptoms rather than slowing renal progression, such as in the latter (12).

We found that nephrologists tended to disagree with all of the potential barriers to discussing CM, except for difficulty determining which patients benefit from CM. PCPs also disagreed or were neutral about most of the barriers, except for limited information on the effectiveness of CM. As a whole, providers surprisingly reported that it was not difficult to initiate a discussion about CM and that they did not fear how their patients would react. Because many physicians find discussing illness trajectories and prognostication challenging (34), these results may have several explanations. First, because of difficulty determining which patients are likely to benefit and limited information on the effectiveness of CM, physicians may only provide a cursory discussion of CM for most patients. Second, some providers may define CM differently than recent descriptions in the literature. Nearly 20%–30% of nephrologists and PCPs indicated that CM could serve as a bridge to kidney transplantation, suggesting differences from traditional CM conceptualization. Third, providers who responded to this survey may have greater interest and expertise in CM, resulting in lower levels of endorsement of otherwise common barriers. In addition, providers may have limited insight on barriers to CM discussion. This could be especially true if providers view CM as most appropriate for their oldest and sickest patients because of the lack of data on effectiveness and optimal patient selection. Additional research on comparative outcomes between dialysis and CM is needed to address these concerns.

Reassuringly, a majority of both nephrologists and PCPs disagree with barriers, such as doubting patient capacity to make the correct decision or letting their own values influence the options that they recommended. These findings suggest that, as research on patient selection for CM and outcomes associated with CM advances, providers may be open to changing their practice patterns appropriately. Although nephrologists felt aware of the effectiveness of CM and patient eligibility for it, PCPs were neutral about these statements. Because nephrologists have relatively recently formulated guidelines for CKD CM (1), we are not surprised that PCPs were less aware of how to approach the topic. Wider dissemination of guidelines for CKD CM may eventually improve PCP knowledge and comfort in this area.

Currently, there is no clear definition of CM for patients with CKD, although one was proposed at a recent KDIGO conference (1,4,5,8,12,25,35). In this survey, we also used definitions described by Murtagh et al. (28) and Jassal et al. (12). Most PCPs and nephrologists correctly identified that CM is used for patients who forego dialysis and includes symptom management and advance care planning. Nonetheless, >40% of both nephrologists and PCPs believed that CM and palliative care were the same. Although both consist of symptom management, CM is the active management of advanced CKD with every intervention but dialysis. Conversely, palliative care frequently does not aim to slow the natural course of CKD (12). However, in practice, these two approaches may overlap, especially when palliative care is offered to maximize quality of life. Because a sizable number of nephrologists and PCPs was unable to distinguish between these terms, we feel that greater clarity in terminology would be helpful.

We also found that, in general, both physician groups experience uncertainty about outcomes of CM compared with those of dialysis. Enhanced knowledge of outcomes of CM compared with dialysis is critical to facilitating accurate, informed shared decision making between providers and patients with advanced CKD. This knowledge gap represents one key barrier to increasing CM discussions in CKD. Finally, we found that the majority of providers knew in which scenarios the RPA guidelines recommend withholding or withdrawing dialysis—this suggests that formalized recommendations may lead to improved awareness.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, although this survey used best practices for electronic implementation, our response rate was low. Respondents may have systematically differed, which may limit generalizability. For example, respondents were more likely to be young, white, men, and in academic practice than the targeted physician sample. These respondents may have had greater interest, training, exposure, or expertise in CM, and this may have influenced our results (e.g., general disagreement with the statement that it is difficult to initiate discussions about CM). In addition, PCPs with larger panels of patients with CKD may have been more likely to complete the survey, and this added experience may have influenced their responses. Second, PCPs may choose to make particular decisions related to CM while collaborating with nephrologists. We did not attempt to ascertain these dynamics. Third, providers may not have accurately recalled their practice patterns or identified barriers to CM. Fourth, for knowledge-related questions, providers may have anecdotal experience that differed from the published literature, which is observational and susceptible to confounding. Nonetheless, our survey findings provide novel information on the knowledge, attitudes, and practice of CM in advanced CKD in the United States.

In conclusion, CM is emerging as a viable alternative to dialysis for older, frail patients with advanced CKD. However, increased dissemination of CM study findings and additional research on optimal patient selection would address provider-endorsed barriers and facilitate individualized discussions with patients. With PCPs and nephrologists, more frequent treatment of pain and use of physical and occupational therapy in patients with advanced CKD should be encouraged. Because PCPs manage many patients with CKD without the input of a nephrologist, additional dissemination of guidelines to PCPs is needed to ensure that they can continue to provide patients appropriate support and guidance and engage them in informed shared decision making (36).

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant K23DK090304 (to K.A.-K.). This work was also supported by a grant from Dialysis Clinic Inc. (to M.U.).

These findings appeared within a poster presentation at Kidney Week 2015 in San Diego, CA, November 3–8, 2015.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “The Provider’s Role in Conservative Care and Advance Care Planning for Patients with ESRD,” on pages 750–752.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.07180715/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, Jha V, Brown EA, Brennan F, Murtagh FE, Naicker S, Germain MJ, O’Donoghue DJ, Morton RL, Obrador GT: Executive summary of the KDIGO Controversies Conference on Supportive Care in Chronic Kidney Disease: Developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney Int 88: 447–459, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renal Physicians Association: Shared Decision Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis, 2nd Ed., Rockville, MD, Renal Physicians Association, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okamoto I, Tonkin-Crine S, Rayner H, Murtagh FE, Farrington K, Caskey F, Tomson C, Loud F, Greenwood R, O’Donoghue DJ, Roderick P: Conservative care for ESRD in the United Kingdom: A national survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 120–126, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, Burns A: Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1611–1619, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K: Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: Comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 1608–1614, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murtagh FEM, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE: Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1955–1962, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown MA, Collett GK, Josland EA, Foote C, Li Q, Brennan FP: CKD in elderly patients managed without dialysis: Survival, symptoms, and quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 260–268, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.De Biase V, Tobaldini O, Boaretti C, Abaterusso C, Pertica N, Loschiavo C, Trabucco G, Lupo A, Gambaro G: Prolonged conservative treatment for frail elderly patients with end-stage renal disease: The Verona experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1313–1317, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morton RL, Snelling P, Webster AC, Rose J, Masterson R, Johnson DW, Howard K: Factors influencing patient choice of dialysis versus conservative care to treat end-stage kidney disease. CMAJ 184: E277–E283, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yong DS, Kwok AO, Wong DM, Suen MH, Chen WT, Tse DM: Symptom burden and quality of life in end-stage renal disease: A study of 179 patients on dialysis and palliative care. Palliat Med 23: 111–119, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connor NR, Kumar P: Conservative management of end-stage renal disease without dialysis: A systematic review. J Palliat Med 15: 228–235, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jassal SV, Kelman EE, Watson D: Non-dialysis care: An important component of care for elderly individuals with advanced stages of chronic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract 119[Suppl 1]: c5–c9, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davison SN: The ethics of end-of-life care for patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2049–2057, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muthalagappan S, Johansson L, Kong WM, Brown EA: Dialysis or conservative care for frail older patients: Ethics of shared decision-making. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2717–2722, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clement R, Chevalet P, Rodat O, Ould-Aoudia V, Berger M: Withholding or withdrawing dialysis in the elderly: The perspective of a western region of France. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 2446–2452, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holley JL, Foulks CJ, Moss AH: Nephrologists’ reported attitudes about factors influencing recommendations to initiate or withdraw dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1284–1288, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Holley JL, Moss AH: Nephrologists’ reported preparedness for end-of-life decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1256–1262, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holley JL, Davison SN, Moss AH: Nephrologists’ changing practices in reported end-of-life decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 107–111, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moss AH, Stocking CB, Sachs GA, Siegler M: Variation in the attitudes of dialysis unit medical directors toward decisions to withhold and withdraw dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 229–234, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samal L, Wright A, Waikar SS, Linder JA: Nephrology co-management versus primary care solo management for early chronic kidney disease: A retrospective cross-sectional analysis. BMC Nephrol 16: 162, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards N, Harris K, Whitfield M, O’Donoghue D, Lewis R, Mansell M, Thomas S, Townend J, Eames M, Marcelli D: The impact of population-based identification of chronic kidney disease using estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) reporting. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 556–561, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdel-Kader K, Fischer GS, Johnston JR, Gu C, Moore CG, Unruh ML: Characterizing pre-dialysis care in the era of eGFR reporting: A cohort study. BMC Nephrol 12: 12, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jolly SE, Navaneethan SD, Schold JD, Arrigain S, Sharp JW, Jain AK, Schreiber MJ, Simon JF, Nally JV: Chronic kidney disease in an electronic health record problem list: Quality of care, ESRD, and mortality. Am J Nephrol 39: 288–296, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.AMA: Physician Masterfile. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about-ama/physician-data-resources/physician-masterfile.page. Accessed November 9, 2015

- 25.Burns A, Davenport A: Maximum conservative management for patients with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Hemodial Int 14[Suppl 1]: S32–S37, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murtagh FE, Murphy E, Shepherd KA, Donohoe P, Edmonds PM: End-of-life care in end-stage renal disease: Renal and palliative care. Br J Nurs 15: 8–11, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medicare Program; ESRD Quality Incentive Program. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/QIP-Details-PY15.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2015

- 28.Murtagh FEM, Cohen LM, Germain MJ: The “no dialysis” option. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 18: 443–449, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ, Diguiseppi C, Wentz R, Kwan I, Cooper R, Felix LM, Pratap S: Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: MR000008, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain AK, Blake P, Cordy P, Garg AX: Global trends in rates of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 533–544, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davison SN: Pain in hemodialysis patients: Prevalence, cause, severity, and management. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 1239–1247, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK, Resnick AL, Unruh ML, Palevsky PM, Levenson DJ, Cooksey SH, Fine MJ, Kimmel PL, Arnold RM: Renal provider recognition of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 960–967, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdel-Kader K, Myaskovsky L, Karpov I, Shah J, Hess R, Dew MA, Unruh M: Individual quality of life in chronic kidney disease: Influence of age and dialysis modality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 711–718, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ: Attitude and self-reported practice regarding prognostication in a national sample of internists. Arch Intern Med 158: 2389–2395, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith C, Da Silva-Gane M, Chandna S, Warwicker P, Greenwood R, Farrington K: Choosing not to dialyse: Evaluation of planned non-dialytic management in a cohort of patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephron Clin Pract 95: c40–c46, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGill RL, Ko TY: Transplantation and the primary care physician. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 18: 433–438, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.