Abstract

Background and objectives

Eating during hemodialysis treatment remains a controversial topic. It is perceived that more restrictive practices in the United States contribute to poorer nutritional status and elevated mortality compared with some other parts of the world. However, in–center food practices in the United States have not been previously described.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

In 2011, we conducted a survey of clinic practices and clinician (dietitian, facility administrator, and medical director) opinions related to in–center food consumption within a large dialysis organization. After the initial survey, we provided clinicians with educational materials about eating during treatment. In 2014, we performed a follow-up survey. Differences in practices and opinions were analyzed using chi-squared tests and logistic regression.

Results

In 2011, 343 of 1199 clinics (28.6%) did not allow eating during treatment, 222 clinics (18.2%) did not allow drinking during treatment, and 19 clinics (1.6%) did not allow eating at the facility before or after treatment. In 2014, the proportion of clinics that did not allow eating during treatment had declined to 22.6% (321 of 1422 clinics), a significant shift in practice (P<0.001). Among the 178 (6.8%) clinics that self-reported that eating was “more allowed” in 2014, the main reason for this shift was an increased focus on nutritional status. Among clinicians, a higher percentage encouraged eating during treatment (53.1% versus 37.4%; P<0.05), and facility administrators and medical directors were less concerned about the seven reasons commonly cited for restricting eating during treatment in 2014 compared with 2011 (P<0.05 for all).

Conclusions

We found that 28.6% and 22.6% of hemodialysis clinics within the United States restricted eating during treatment in 2011 and 2014, respectively, a rate more than double that found in an international cohort on which we previously published. However, practices and clinician opinions are shifting toward allowing patients to eat. Additional research is warranted to understand the effect that these practices have on patient outcomes and outline best practices.

Keywords: nutrition, blood pressure, hemodialysis, hypotension, follow-up studies, humans, logistic models, nutritional status, renal dialysis, United States

Introduction

Maintenance hemodialysis (HD) is a catabolic procedure that is associated with poor nutritional status (1,2). In addition to being catabolic, time spent undergoing treatment provides an added barrier to achieving adequate dietary intake and has been associated with significant reductions in nutrient consumption compared with nontreatment days (3,4). Patients who eat during treatment have higher intake on treatment days (3), and the consumption of food or nutritional supplements during treatment has been shown to improve nutritional status (5–9) and quality of life (10) and is associated with significant reductions in mortality (11,12). Despite these observations, allowing food or providing nutritional supplements during HD remains a controversial topic because of concerns that include postprandial hemodynamics, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, treatment efficiency, choking, pests, and infection control (13–15).

Consistent with the controversy, clinic practices related to in–center food and supplement consumption vary widely throughout the world (15). There is a perception that clinics in North America and particularly, the United States have more restrictive practices that contribute to reductions in albumin, poorer nutritional status, and elevated mortality (13,16). However, data regarding practices on in–center food and supplement intake in the United States are scarce. Therefore, we conducted a survey of clinics within a large HD provider in the United States without a company-wide policy to determine clinic practices and clinician perceptions on in-center nutrition.

Materials and Methods

As part of a quality initiative, we developed a 16-item survey to determine clinic practices and staff perceptions about eating during HD. In the first part of the survey, questions focused on individual clinic practices related to in-center intake of food, beverages, and supplements. In the second part of the survey, we asked registered dietitians (RDs), facility administrators (FAs), and medical directors (MDs) at each clinic about their own opinions on in–center food consumption. Additionally, clinicians were asked for the reasons that they believed nutrition should be restricted or allowed (RDs only). This survey was undertaken as a quality assurance effort to assess the current practice within this dialysis company. The questions were validated by a small group of renal dietitians, and the survey protocol was determined to be a quality initiative on the basis of guidelines reviewed with an institutional review board.

In July of 2011, a link to this survey was sent to the RDs at all clinics in a large dialysis organization located within the United States. The RD at each clinic was tasked with filling out the survey. For questions that asked about clinician opinions, the RD obtained survey responses from the FA and MD. If the RD was unable to speak with either the FA or MD, they were able to check that they were not available, and these data were excluded from analysis.

After analysis of the original survey, we identified a need for education given the number of clinics that allowed food consumption during treatment. Therefore, we developed educational materials about eating during HD treatment (Eating at Treatment [EAT]) to better support safe and practical aspects of food consumption during treatment (Supplemental Material). RDs at each clinic were trained about EAT, and the educational materials were made available on the company intranet in 2013. Guidelines for both patients and staff included information on the type and quantity of foods to bring to treatment, the timing of food consumption, practical instructions on foods easiest to transport and consume at treatment, and tips for food safety. Patients were encouraged to avoid foods that required heating, might be difficult to unwrap, could not be eaten with one hand, and might drip or crumble. In addition, there were reminders to bring phosphate binders if prescribed. Patient education materials included kidney-friendly foods to bring to the center and information on quality protein sources and amounts to include. Materials were provided as handouts and interactive tools, and they were available in both English and Spanish. In 2014, we sent a follow-up survey to the RDs at all clinics within the organization that contained additional questions about changes in clinic practices over the last 3 years.

Data from both surveys were entered and analyzed in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Clinic practices and clinician responses were compared using a chi-squared, McNemar–Bowker, or logistic regression analysis when necessary. For regression analysis, position (RD, FA, and MD), year (2011 and 2014), and the interaction term were included in the model. When the interaction term was significant, individual differences were determined by post hoc analysis. Significance was determined using an α of 0.05. Data are presented as the numbers and proportions of responses.

Results

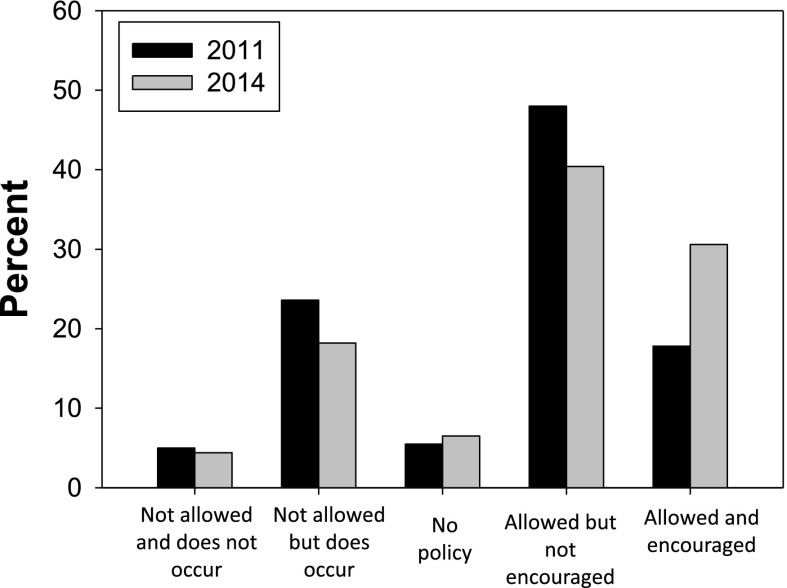

In 2011, we received 1199 unique responses from 1665 possible clinics (72.0%). Eating food during HD treatment was restricted in 343 clinics (28.6%) (Figure 1). Slightly fewer clinics restricted drinking beverages other than water during HD (222 clinics; 18.5%), and just 19 clinics (1.6%) did not allow eating at the clinic either before or after HD. When asked about their practice for allowing nutritional supplements (protein bars or liquid supplements), 215 clinics (17.9%) had different practices compared with eating food during HD treatment. When these responses were separated by clinic policy on eating during treatment (either allowed, no policy, or not allowed), 91 clinics (11.5%) that allowed eating, five clinics (7.6%) that had no policy on eating, and 119 (34.7%) of the clinics that did not allow eating during treatment had different policies related to nutritional supplements.

Figure 1.

Comparison of clinic practices for eating during hemodialysis treatment in 2011 and 2014.

In 2014, we received 1422 responses from 2152 possible clinics (66.1%). The clinic practices related to eating during HD are presented in Figure 1. In short, 321 clinics (22.6%) restricted eating during HD, and there was an overall shift in clinic practice from 2011 (Figure 1) (P<0.001). Furthermore, there was a similar shift in practice among the 845 clinics that provided data in both 2011 and 2014 (P<0.001). Among these clinics that provided data in both years, the largest change in practice was seen in the category that both allowed and encouraged eating (156 clinics [18.5%] in 2011 versus 263 clinics [31.1%] in 2014).

When asked specifically about how their clinic practice had changed since 2011, slightly more clinics (178 [12.5%] versus 148 [10.4%]) said that eating during HD was “more allowed” versus “more restricted.” Among these 178 clinics that changed practices toward eating being “more allowed” during HD treatment, the reasons for change (multiple answers allowed) included an increased focus on nutritional status (122; 68.5%), an increased focus on dietary intake on dialysis days (82; 46.1%), effectiveness of oral nutritional supplement programs (64; 36.0%), perceived positive experiences with eating during HD (44; 24.7%), availability of EAT educational materials (42; 23.6%), and change in FA (42; 23.6%) or MD (15; 8.4%) opinion. Among the 148 clinics that changed their practice toward “more restriction” during HD treatment, 89 (60.1%) of those perceived a negative experience with eating during HD. The other top reasons for more restrictive policies included a change in FA opinion (70; 47.3%), a change in MD opinion (32; 21.6%), and availability of EAT educational materials (18; 12.2%).

The differences in clinician opinions in the 2011 and 2014 samples are presented in Table 1. There were significant group differences in clinician opinions on eating during HD, with RDs being the most likely to encourage (RD [2011 and 2014 combined] at 40.5% versus FA at 29.4% and MD at 27.8%; P<0.001) or strongly encourage (RD [2011 and 2014 combined] at 17.3% versus FA at 9.9% versus MD at 9.5%; P<0.001) eating during HD. However, the opinions of all three groups (RD, MD, and FA) were more favorable toward eating during HD treatment in 2014 compared with in 2011 (P<0.05).

Table 1.

Clinician opinions on eating during hemodialysis treatment

| Position and Year | N | Strongly Discourage N (%) | Discourage N (%) | No Opinion N (%) | Encourage N (%) | Strongly Encourage N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered dietitian | ||||||

| 2011 | 1192 | 275 (23.1)a | 264 (22.1) | 95 (8.0) | 446 (37.4) | 112 (9.4) |

| 2014 | 1408 | 163 (11.6)a,b | 204 (14.5)c | 97 (6.9)c | 607 (43.1)c | 337 (23.9)c |

| Total | 2600 | 438 (16.8) | 468 (18.0)d | 192 (7.4)d | 1053 (40.5)d | 449 (17.3)d |

| Facility administrator | ||||||

| 2011 | 1003 | 316 (31.5)e | 238 (23.7) | 131 (13.1) | 250 (24.9) | 68 (6.8) |

| 2014 | 1238 | 312 (25.2)b,e | 238 (19.2)c | 126 (10.2)c | 409 (33.0)c | 153 (12.4)c |

| Total | 2241 | 628 (28.0) | 476 (21.2)f | 257 (11.5)f | 659 (29.4)f | 221 (9.9)f |

| Medical director | ||||||

| 2011 | 828 | 255 (30.8)e | 159 (19.2) | 158 (29.1) | 209 (25.2) | 47 (5.7) |

| 2014 | 978 | 235 (24.0)b,e | 156 (16.0)c | 169 (17.3)c | 293 (30.0)c | 125 (12.8)c |

| Total | 1806 | 490 (27.1) | 315 (17.4)d | 327 (18.1)d,f | 502 (27.8)f | 172 (9.5)f |

Results of the regression analysis that included position, year, and the interaction term are shown. When the interaction terms or main effects were significant, individual differences were determined by post hoc analysis on the respective category.

Significant difference versus facility administrator in given year (P<0.05).

Significant difference between 2011 and 2014 in a specific position (P<0.05).

Significant difference between 2011 and 2014 (P<0.05).

Significant difference versus facility administrators (P<0.05).

Significant difference versus registered dietitians in given year (P<0.05).

Significant difference versus registered dietitians (P<0.05).

Reasons supporting practitioner beliefs about eating are presented in Table 2. Among all clinicians (RD, FA, and MD) who did not support eating during HD, there were smaller percentages who were concerned about choking (76.5% in 2011 versus 67.0% in 2014; P<0.001) and spills or pests (59.3% in 2011 versus 48.2% in 2014; P<0.001) as the reason to restrict eating in 2014 compared with in 2011. Furthermore, MDs and FAs (but not RDs; interaction terms P≤0.05) were less concerned about clinic policy (FA: z = 3.70; P<0.001; MD: z = 4.41; P<0.001), infection control (FA: z = 1.78, P=0.08; MD: z = 4.75; P<0.001), hypotension (FA: z = 1.95; P=0.05, MD: z = 3.49; P<0.001), GI distress (FA: z = 2.23, P<0.03; MD: z = 4.50; P<0.001), and reduced treatment efficiency (FA: z = 2.36, P<0.02; MD: z = 2.80; P<0.01) in 2014 compared with 2011. Write-in answers also revealed that a few FAs and MDs were concerned that eating during treatment may potentially cause damage to the access and that at least one state may have regulations that prevent clinics from having more lenient in–center nutrition practices.

Table 2.

Reasons supporting practitioner belief in restricting eating during hemodialysis treatment

| Position and Year | N | Facility Policy N (%) | Infection Control N (%) | Hypotension N (%) | Choking N (%) | Gastrointestinal Distress N (%) | Reduced Kt/V N (%) | Spills/Pests N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered dietitian | ||||||||

| 2011 | 539 | 174 (32.3) | 383 (71.1) | 363 (67.3) | 436 (80.1) | 402 (74.6)a | 55 (10.2) | 339 (62.9) |

| 2014 | 367 | 114 (31.1) | 268 (73.0)a | 253 (68.9) | 275 (74.9)b | 263 (71.1)a | 48 (13.1) | 206 (56.1)b |

| Total | 906 | 288 (31.8) | 651 (71.9) | 616 (68.0) | 711 (78.5)a | 665 (73.4) | 103 (11.4) | 545 (60.2) |

| Facility administrator | ||||||||

| 2011 | 554 | 209 (37.7) | 398 (71.8) | 390 (70.4) | 415 (74.9) | 338 (61.0)c | 107 (19.3)c | 343 (61.9) |

| 2014 | 550 | 149 (27.1)d | 368 (66.9)c | 358 (65.1) | 382 (69.5)b | 300 (54.5)c,d | 77 (15.4)d | 290 (52.7)b |

| Total | 1104 | 358 (32.4) | 766 (69.4) | 748 (67.8) | 797 (72.2)c | 638 (57.8) | 184 (16.7) | 633 (57.3) |

| Medical director | ||||||||

| 2011 | 414 | 162 (39.1)c | 259 (62.6)a,c | 305 (73.7)c | 302 (72.9) | 246 (59.4)c | 81 (19.6)c | 212 (51.2) |

| 2014 | 391 | 95 (24.3)c,d | 180 (46.0)a,c,d | 243 (62.1)c,d | 220 (66.3)b | 171 (43.7)a,c,d | 48 (12.3)d | 134 (34.3)b |

| Total | 805 | 257 (31.9) | 439 (54.5) | 548 (68.1) | 522 (64.8)e,f | 417 (51.8) | 129 (16.0) | 346 (43.0)e,f |

Results of the regression analysis that included position, year, and the interaction term are shown. When the interaction terms or main effects were significant, individual differences were determined by post hoc analysis on the respective category.

Significant difference versus facility administrator in given year (P<0.05).

Significant difference between 2011 and 2014 (P<0.05).

Significant difference versus registered dietitians in given year (P<0.05).

Significant difference between 2011 and 2014 in a specific position (P<0.05).

Significant difference versus registered dietitians (P<0.05).

Significant difference versus facility administrators (P<0.05).

Finally, among RDs who supported eating during HD, there was a higher proportion who cited an improved ability to meet caloric needs as a reason to allow in–center food consumption in 2014 compared with in 2011 (76.4% in 2011 versus 83.1% in 2014; P<0.01) (Table 3). However, smaller percentages of RDs cited blood glucose control (88.3% in 2011 versus 80.1% in 2014; P<0.001) and difficulty enforcing a no-eating policy (40.8% in 2011 versus 34.2% in 2014; P<0.02) as reasons to support eating during treatment. The opportunity to teach patients remained a strong reason for RD support of incenter food consumption in 2011 and 2014, and the proportion did not significantly change (74.0% in 2011 versus 70.8% in 2014; P=0.18).

Table 3.

Reasons registered dietitians supported eating during hemodialysis

| Position and Year | N | Meeting Caloric Needs N (%) | Blood Glucose N (%) | Difficulty Enforcing Policy N (%) | Teaching Opportunity N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered dietitian | |||||

| 2011 | 554 | 423 (76.4) | 489 (88.3) | 226 (40.8) | 410 (74.0) |

| 2014 | 944 | 784a (83.1) | 756a (80.1) | 323a (34.2) | 668 (70.8) |

Significant change from 2011 (P<0.05).

Discussion

The major finding from this study was that 28.6% and 22.6% of HD clinics within this United States cohort did not allow patients to eat during HD treatment in 2011 and 2014, respectively. This is a rate more than double that from an international cohort on which we published last year (15). It is unclear what explains the difference in clinic practices between the United States and many other places around the world. One possible explanation is that higher ultrafiltration rates observed in the United States may contribute to greater complications during treatment (17). Furthermore, our survey identified that local legislative restrictions on in–center food consumption may also limit intake in some regions of the United States. Overall, it is likely that many factors are contributing to these more restrictive practices and that understanding these factors may be an important step in outlining best practices.

Although overall, the rate of restriction was high in this United States cohort, we found a significant reduction in the proportion of clinics that restricted eating during treatment in 2014 compared with in 2011. Among clinics that reported that eating was “more allowed,” the primary reason for this shift was an increased emphasis on nutritional status and dietary intake on treatment days. There is a strong and consistent relationship between nutrition status and outcomes in patients on HD (18–22), and it has been hypothesized that restricting intradialytic nutrition contributes to the lower serum albumin and higher mortality rates observed in the United States (13,16). Indeed, several recent review articles (13,14,23) and observational studies (11,12) have emphasized intradialytic oral nutrition as a way to improve nutritional status and outcomes, especially in malnourished patients. Similarly, restricting intradialytic oral nutrition may have deleterious effects on the nutritional status of patients who are not currently classified as malnourished (6), although this is not as well demonstrated in the literature. Therefore, future work should aim to identify the effect that clinic practices related to in-center nutrition have on patient nutritional status and outcomes, especially in patients who may not currently be malnourished.

Additionally, our survey also revealed that clinic practices on in-center nutrition differed by both time (during, before, or after treatment) and type (food, supplements, or beverage). Despite these differing practices, there are little data comparing the effects of nutrition composition or timing on patient outcomes. This is especially true of studies that have examined the potential complications related to eating during HD (reviewed in ref. 14). The majority of these trials have involved large, mixed macronutrient, solid meals consumed after a significant amount of ultrafiltration. In other populations, meal composition (24,25), size (26), and timing are important factors that contribute to postprandial hemodynamics. Given the large number of clinics around the world that allows in-center nutrition, understanding how these factors influence patient safety may be an important topic for future research.

Consistent with changes in clinical practice, we found 20.2%, 13.7%, and 11.9% increases in the percentages of RDs, FAs, and MDs, respectively, who encouraged eating during treatment in 2014 compared with 2011. These changes in opinion may reflect a growing literature showing benefits to feeding patients during treatment (5–8,10–12). Indeed, we found that an increased focus on nutritional status and a desire to increase patient intake on treatment days were major reasons for the observed shifts in clinic practice. Additionally, we found that fewer clinicians were concerned about seven factors frequently cited to restrict eating during treatment in 2014 compared with in 2011. Despite the overall reduction in clinicians who cited each of the seven reasons to restrict eating, clinicians remained concerned about all of these factors. This was especially true of clinical concerns, such as hypotension, choking, and GI symptoms, which were a concern in a greater percentage of clinicians than were environmental concerns, such as spills and pests, in both years. When we asked an international cohort about their experiences with these same factors, we found that, with the exception of intradialytic hypotension and GI symptoms, most concerns were rarely witnessed in clinical practice (15). These data may highlight the difficulty that clinicians face in balancing the potential for acute complications, which are easily attributed to eating, with the observed benefits, such as reduced mortality, that may be difficult to relate to intradialytic nutrition. Additional research into the prevalence of these potential complications and ways to minimize their risk and a better understanding of when patients are at risk of complications may help clinicians to make more informed decisions.

The major limitation to this study is that all of the data comes from a single dialysis provider. This may limit its generalizability to all clinics within the United States. However, this still represents a significant portion of clinics within the United States and supports previous suggestions that United States practices may be more restrictive compared with the rest of the world (15). Furthermore, no clinic or clinician data were available to describe the population or the influence that these policies had on patient nutritional status. Despite these limitations, these data represent a large cohort of clinics and are the first to describe clinic practices and clinician perceptions related to in-center nutrition within the United States. Given the recent observation that intradialytic oral supplementation programs significantly reduce mortality, eating during treatment may represent a feasible strategy to improve patient care and outcomes in patients who can tolerate it, and it deserves additional investigation.

In 2011, we found that 28.6% of 1199 clinics within a large dialysis provider in the United States restricted eating food during HD treatment. By 2014, we found a significant shift in clinic practices, so that food intake was restricted in just 22.6% of 1422 clinics. The main reasons for this shift in practice were an increased emphasis on patient nutritional status and a reduction in clinician concerns related to eating during treatment. Despite the observed shifts, clinic practices and clinician opinions remain split on allowing patients to eat or consume supplements during treatment. Given the number of clinics that allow patients to eat during treatment, clinicians and patients may benefit from guidelines for safe and practical dietary intake during treatment. Future research should target ways to minimize the risk associated with eating during treatment and explore the influence that this practice has on global differences in nutritional status and outcomes, especially in patients who may not be classified as malnourished.

Disclosures

D.B., M.B., M.S., and B.B. are all employed by DaVita Healthcare Partners, Inc. K.W., S.S., and B.K. have no disclosures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the teammates at the >2000 DaVita Healthcare Partners, Inc. clinics who work every day to take care of patients and also, ensure the extensive data collection and survey completion on which our work is based. We thank the DaVita Nutrition Services Team for managing the survey process. The DaVita Nutrition Services team is committed to engaging patients in their nutrition care and improving their quality of life.

Significant portions of these data were previously presented at scientific conferences in abstract form: Benner D, Davis M, Stasios M, Burgess M: Kidney Res Clin Pract 2012; Burgess M, Benner D, Stasios M, Brosch B: J Am Soc Nephrol 684A, 2014; and Stasios M, Burgess M, Brosch B, Mutell R, Benner D: J Ren Nutr 25: 143, 2015.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Peanuts or Pretzels? Changing Attitudes about Eating on Hemodialysis,” on pages 747–749.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.09270915/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fouque D, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple J, Cano N, Chauveau P, Cuppari L, Franch H, Guarnieri G, Ikizler TA, Kaysen G, Lindholm B, Massy Z, Mitch W, Pineda E, Stenvinkel P, Treviño-Becerra A, Wanner C: A proposed nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for protein-energy wasting in acute and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 73: 391–398, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borah MF, Schoenfeld PY, Gotch FA, Sargent JA, Wolfsen M, Humphreys MH: Nitrogen balance during intermittent dialysis therapy of uremia. Kidney Int 14: 491–500, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burrowes JD, Larive B, Cockram DB, Dwyer J, Kusek JW, McLeroy S, Poole D, Rocco MV; Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study Group: Effects of dietary intake, appetite, and eating habits on dialysis and non-dialysis treatment days in hemodialysis patients: Cross-sectional results from the HEMO study. J Ren Nutr 13: 191–198, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Martins AM, Dias Rodrigues JC, de Oliveira Santin FG, Barbosa Brito Fdos S, Bello Moreira AS, Lourenço RA, Avesani CM: Food intake assessment of elderly patients on hemodialysis. J Ren Nutr 13: 191–198, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Pupim LB, Majchrzak KM, Flakoll PJ, Ikizler TA: Intradialytic oral nutrition improves protein homeostasis in chronic hemodialysis patients with deranged nutritional status. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3149–3157, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veeneman JM, Kingma HA, Boer TS, Stellaard F, De Jong PE, Reijngoud DJ, Huisman RM: Protein intake during hemodialysis maintains a positive whole body protein balance in chronic hemodialysis patients. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284: E954–E965, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caglar K, Fedje L, Dimmitt R, Hakim RM, Shyr Y, Ikizler TA: Therapeutic effects of oral nutritional supplementation during hemodialysis. Kidney Int 62: 1054–1059, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomayko EJ, Kistler BM, Fitschen PJ, Wilund KR: Intradialytic protein supplementation reduces inflammation and improves physical function in maintenance hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr 25: 276–283, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Braglia A, Chow J, Kwon O, Kuwae N, Colman S, Cockram DB, Kopple JD: An anti-inflammatory and antioxidant nutritional supplement for hypoalbuminemic hemodialysis patients: A pilot/feasibility study. J Ren Nutr 15: 318–331, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott MK, Shah NA, Vilay AM, Thomas J 3rd, Kraus MA, Mueller BA: Effects of peridialytic oral supplements on nutritional status and quality of life in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr 19: 145–152, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Ladik V, Meyer KB, Zager PG, Johnson DS: Oral intradialytic nutritional supplement use and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 276–285, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacson E Jr., Wang W, Zebrowski B, Wingard R, Hakim RM: Outcomes associated with intradialytic oral nutritional supplements in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: A quality improvement report. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 591–600, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Ikizler TA: Let them eat during dialysis: An overlooked opportunity to improve outcomes in maintenance hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr 23: 157–163, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kistler BM, Fitschen PJ, Ikizler TA, Wilund KR: Rethinking the restriction on nutrition during hemodialysis treatment. J Ren Nutr 25: 81–87, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kistler B, Benner D, Burgess M, Stasios M, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Wilund KR: To eat or not to eat—international experiences with eating during hemodialysis treatment. J Ren Nutr 24: 349–352, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Combe C, McCullough KP, Asano Y, Ginsberg N, Maroni BJ, Pifer TB: Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) and the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS): Nutrition guidelines, indicators, and practices. Am J Kidney Dis 44[Suppl 2]: 39–46, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foley RN, Hakim RM: Why is the mortality of dialysis patients in the United States much higher than the rest of the world? J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1432–1435, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kilpatrick RD, Kuwae N, McAllister CJ, Alcorn H Jr., Kopple JD, Greenland S: Revisiting mortality predictability of serum albumin in the dialysis population: Time dependency, longitudinal changes and population-attributable fraction. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 1880–1888, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rambod M, Bross R, Zitterkoph J, Benner D, Pithia J, Colman S, Kovesdy CP, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Association of Malnutrition-Inflammation Score with quality of life and mortality in hemodialysis patients: A 5-year prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 298–309, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rambod M, Kovesdy CP, Bross R, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Association of serum prealbumin and its changes over time with clinical outcomes and survival in patients receiving hemodialysis. Am J Clin Nutr 88: 1485–1494, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Block G, McAllister CJ, Humphreys MH, Kopple JD: Appetite and inflammation, nutrition, anemia, and clinical outcome in hemodialysis patients. Am J Clin Nutr 80: 299–307, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Streja E, Kovesdy CP, Oreopoulos A, Noori N, Jing J, Nissenson AR, Krishnan M, Kopple JD, Mehrotra R, Anker SD: The obesity paradox and mortality associated with surrogates of body size and muscle mass in patients receiving hemodialysis. Mayo Clin Proc 85: 991–1001, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fissell R, Hakim RM: Improving outcomes by changing hemodialysis practice patterns. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 22: 675–680, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luciano GL, Brennan MJ, Rothberg MB: Postprandial hypotension. Am J Med 123: 281.e1–281.e6, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jansen RW, Peeters TL, Van Lier HJ, Hoefnagels WH: The effect of oral glucose, protein, fat and water loading on blood pressure and the gastrointestinal peptides VIP and somatostatin in hypertensive elderly subjects. Eur J Clin Invest 20: 192–198, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puvi-Rajasingham S, Mathias CJ: Effect of meal size on post-prandial blood pressure and on postural hypotension in primary autonomic failure. Clin Auton Res 6: 111–114, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.