Abstract

Background and objectives

There is growing interest in efforts to enhance advance care planning for patients with kidney disease. Our goal was to elicit the perspectives on advance care planning of multidisciplinary providers who care for patients with advanced kidney disease.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Between April and December of 2014, we conducted semistructured interviews at the Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System with 26 providers from a range of disciplines and specialties who care for patients with advanced kidney disease. Participants were asked about their perspectives and experiences related to advance care planning in this population. Interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, and analyzed inductively using grounded theory.

Results

The comments of providers interviewed for this study spoke to significant system–level barriers to supporting the process of advance care planning for patients with advanced kidney disease. We identified four overlapping themes: (1) medical care for this population is complex and fragmented across settings and providers and over time; (2) lack of a shared understanding and vision of advance care planning and its relationship with other aspects of care, such as dialysis decision making; (3) unclear locus of responsibility and authority for advance care planning; and (4) lack of active collaboration and communication around advance care planning among different providers caring for the same patients.

Conclusions

The comments of providers who care for patients with advanced kidney disease spotlight both the need for and the challenges to interdisciplinary collaboration around advance care planning for this population. Systematic efforts at a variety of organizational levels will likely be needed to support teamwork around advance care planning among the different providers who care for patients with advanced kidney disease.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, advance care planning, care complexity, multidisciplinary, end-of-life, communication, cooperative behavior, decision making, grounded theory, humans, renal dialysis

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is the process of communication between patients, family members, and providers to clarify the patient’s values, goals, and preferences for care if they were seriously ill or dying (1,2). There is growing interest in efforts to enhance ACP for patients with advanced kidney disease (3–6). In this population, low rates of completion of advance directives (7) and low levels of prognostic awareness (8) coexist with intensive patterns of end-of-life care focused on life prolongation (9,10).

There is emerging evidence that interventions to support ACP among patients with advanced kidney disease can lead to better preparation for end-of-life treatment decisions among patients and their surrogate decision makers (11,12) and more favorable bereavement outcomes among surrogates (12). Patients with kidney disease report being open to engaging in ACP but expect health care providers to initiate these conversations (13–17). Barriers to ACP among renal providers include inadequate knowledge and training in communication, belief that ACP may be distressing for patients, concerns that ACP is too time consuming, difficulty estimating prognosis, and uncertainty about their role in ACP (18–22).

Prior studies of provider perspectives on ACP among patients with advanced kidney disease were conducted almost exclusively among nephrologists and renal or dialysis unit staff (13,18–24). Because many of these patients have other serious health conditions and may be cared for by a range providers in a variety of settings during the course of illness (25), these earlier studies may have failed to capture and address the complexity of care for this patient population. We undertook a qualitative study to gain insight from providers from a range of disciplines and specialties who care for patients with advanced kidney disease to identify potential opportunities to enhance ACP for this population.

Materials and Methods

Participants

We approached providers who routinely care for patients with advanced kidney disease (defined as a sustained eGFR≤20 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or on dialysis) from different disciplines and specialties (cardiology, geriatric medicine, intensive care, nephrology, nursing, nutrition, palliative care, physiatry, primary care, social work, and vascular surgery) at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Puget Sound Health Care System (Seattle, WA). Eligible providers were emailed an invitation to participate in the study, and those who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form. The protocol for the overall study was reviewed and approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

Participants completed a 45- to 60-minute semistructured, one-on-one interview by phone or in person to elicit their perspectives and experiences related to ACP for patients with advanced kidney disease (Supplemental Table 1). Participants were prompted to provide details and examples to enhance the richness of the data. The interviews were conducted by one coinvestigator (J.S.), digitally recorded, and transcribed verbatim.

Analyses

Data analysis was based on grounded theory (26). To ensure that the analysis was not biased by the researchers’ expectations, we began with open coding to capture important themes from the transcripts using an emergent rather than an a priori approach. We used Atlas.ti software to organize the coding process (Atlas.ti; Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Each transcript was coded by at least two of four coauthors (A.M.O., J.S., L.V.M., or E.K.V.). One coauthor (J.S.) then reviewed all coded transcripts and refined, condensed, and organized open codes into code families (groupings of codes with related meaning). Emergent codes were added throughout the analysis, and in vivo codes were selected as exemplars (27). Five coauthors (A.M.O., J.S., L.V.M., J.S.T., and E.K.V.) iteratively reviewed and discussed the codes and code families, returned to the transcripts to ensure that coding remained well grounded in the data, and built consensus by open discussion of differing interpretations of the data, choice of codes, and thematic organization (28).

Results

In total, 35 providers routinely involved in the care of patients with advanced kidney disease were invited to participate in this study. Of these, 26 (74%) agreed to participate, including 13 physicians (from cardiology, intensive care, nephrology, palliative care, primary care, physiatry, and vascular surgery), six nurses (including nurses and nurse practitioners in palliative care, nephrology, and dialysis), three dialysis technicians, two dieticians, and two social workers. Thematic saturation was reached after analyzing data from 22 interviews. The remaining four interviews were reviewed for concurrence (29). The mean age of providers was 49.3±9.7 years old (range =28–65 years old), 46% were men, 77% were white, and the average time in clinical practice was 18±9.0 years (ranging from 1 to 32 years).

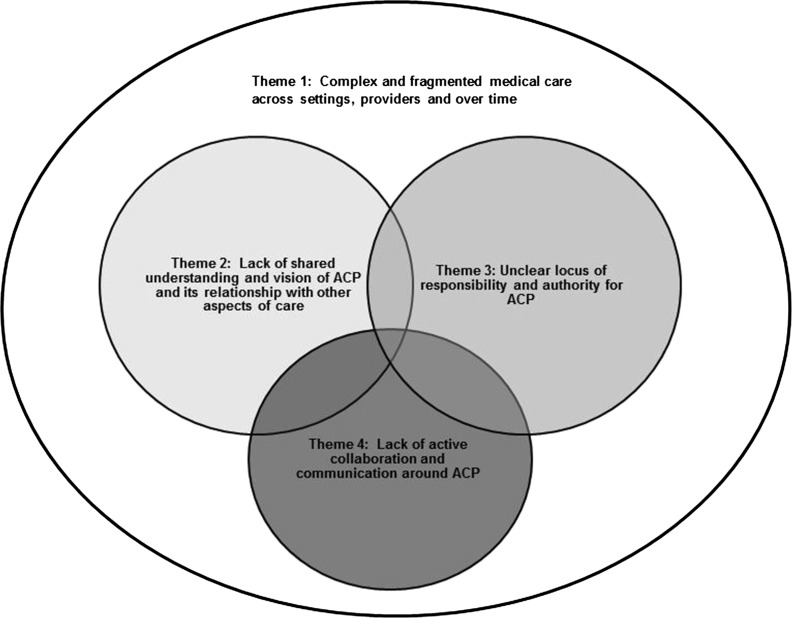

Although all providers interviewed for this study seemed to appreciate the potential value of ACP for patients with kidney disease, the following four interrelated themes pertaining to barriers to ACP in this population emerged from provider interviews (Figure 1). An overarching theme was that medical care for these patients is complex and fragmented across settings and providers and over time (theme 1). This theme provided a backdrop for the following three subsidiary themes: lack of a shared understanding and vision of ACP and its relationship with other aspects of care (theme 2), unclear locus of responsibility and authority for ACP (theme 3), and lack of active collaboration and communication around ACP (theme 4) among providers.

Figure 1.

Emergent themes. The figure represents a qualitative rather than a quantitative description of the relationship between themes. ACP, advance care planning.

Theme 1: Medical Care for Patients with Advanced Kidney Disease Is Complex and Fragmented across Settings and Providers and over Time

Providers tended to move in and out of the care of individual patients over time. Their reach was often confined to particular phases in the illness trajectory, clinical settings, or roles. Primary care providers reported becoming less involved after their patients started dialysis (Table 1, exemplar quotation 1). Some expressed concern about the way that decisions about dialysis sometimes unfolded and provided examples of situations where they did not feel that their patients had been offered a meaningful choice or where they questioned the wisdom of initiating dialysis in particular patients (Table 1, exemplar quotation 2). Some lacked a clear understanding of how decisions about dialysis were made, and some had the sense that such decisions were often shaped by wider social forces and treatment imperatives beyond the control of individual providers (Table 1, exemplar quotation 3).

Table 1.

Complex and fragmented medical care across settings and providers and over time (theme 1)

| Exemplar Quotation No. | Source | Exemplar Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Primary care provider | Once patients go on dialysis, I usually feel like there's not that much more to do. So, for example, from my perspective, because I feel like all the decisions about medications, all get factored into dialysis. Sure, I could do some preventive health, but … the dialysis is relevant to every aspect of their care and so I usually then will say, “I'm happy to follow you. I'm just not sure what I'm doing for you.” So, most of those patients would transition over the years to being followed solely by nephrology. |

| 2 | Primary care provider | I just had one patient who was like 85 and he ended up on dialysis … I don’t think the decision was, I don’t know, it just didn’t go like you would hope it would for someone that age. I don’t think he was presented with all of his options, in terms of not doing anything. I think he was only presented with like, “You have to do this, otherwise you’ll die.” I think it’s in an acute setting, when people are really sick. It’s different than when it’s a slow progression. Some people just end up getting dialysis. |

| 3 | Primary care provider | There are people who are just in the intensive care unit for months and … dialysis was keeping them alive. And I know patients get discharged to these chronic centers and get left on dialysis for a very long time. I feel like that is a national conversation … in nephrology. You know, I always wondered “Would Queen Elizabeth get put on dialysis at her age?” I mean, in America, she would, but I don’t know about in England. |

| 4 | Renal nurse | You know I don't see chronic kidney disease patients in clinic. I see them when they are already very advanced. I can tell you that commonly that population of patients that I am involved with are completely blindsided. They are so overwhelmed by the notion that they are going to need to start dialysis. |

| 5 | Dialysis nurse (responding to a question about when ACP should be conducted) | Um in the clinic visits! We are like out of the realm a little bit, as far as dialysis unit staff. The clinics here are run in a different area, where they have staff for that. |

| 6 | Dialysis nurse | So, it’s up to the physicians at that point … our social worker gets involved and some of our other renal staff, but it primarily falls on the physicians to start passing on that information, early on. Um, and I don't think that always gets done maybe as well as it should. |

| 7 | Palliative care nurse | I think this is kind of my pet peeve, when people have really serious life–threatening illness, a lot of times the social worker will approach them and say “well … do you want to do this advance directive?,” and if they say “no,” then I think the providers should be encouraging them to do them. Because when we’re trying to make decisions and the person has a decision maker, let’s say when a person has some cognitive impairment, you need a shared decision–making model to even make a decision, and if that surrogate decision maker has not been identified ahead of time, you know, it really, really makes the process a lot more hard. |

| 8 | Primary care provider | It seems like most people … they end up in the hospital really sick, they get out, or there is someone that starts talking to them in the hospital about what they want to do, what their directives are. |

| 9 | Primary care provider | But, of course, I think, in America, we tend to offer dialysis to whoever wants it! … But I don’t think that’s always right. When I was attending at the university one time … we actually put a guy who was 92 on dialysis. My ward residents were just having heart attacks! “What are we actually doing?,” but … nephrology agreed to do it. And I think he had one dialysis session and said “I don't want this” and then a week later, died. |

| 10 | Dialysis nurse | So that is more patients in the ICU, and we are not there to make those decisions, because when the patients are in ICU, families make those decisions (dialysis nurses are not a part of that). Those are with the doctors and families directly. |

ACP, advance care planning; ICU, intensive care unit.

Providers involved later in the course of illness often wondered why patients were not better prepared for the advanced stages of kidney disease and were struck by how “blindsided” patients often seemed when faced with decisions about dialysis (Table 1, exemplar quotation 4). Dialysis unit staff became involved later in the illness trajectory, and many felt that ACP should have been initiated much earlier in the course of illness in the clinic (Table 1, exemplar quotation 5) by nephrologists (Table 1, exemplar quotation 6). A palliative care nurse—who reported assisting with hospice referrals—shared that her “pet peeve” was when providers involved early on did not help patients to identify a surrogate decision maker (Table 1, exemplar quotation 7).

Compartmentalization and fragmentation of care also occurred across settings. Many providers recognized the importance of addressing ACP in the clinic setting with trusted providers but acknowledged that, most commonly, these discussions occurred in the acute setting with a provider that the patient did not know well (Table 1, exemplar quotation 8). Compartmentalization within settings was also challenging. A general internist described a situation in which she did not follow the rationale for dialysis initiation in a very elderly patient while rotating on the inpatient medicine service (Table 1, exemplar quotation 9). Although the dialysis unit at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System is located in the hospital and provides both inpatient and outpatient dialysis, one dialysis nurse explained that she was not able to participate in the end-of-life care of her patients on dialysis when they were seriously ill in the intensive care unit, because “dialysis nurses are not part of that” (Table 1, exemplar quotation 10).

Theme 2: Lack of a Shared Understanding and Vision of ACP and Its Relationship with Other Aspects of Care

Providers differed in their understanding of ACP and its relationship to other aspects of care. Some providers viewed ACP as a discrete task or a series of tasks, such as completion of advance directives and discussions about code status (Table 2, exemplar quotation 1). Some viewed these as potentially standalone procedures that did not need to be closely integrated with other aspects of care (Table 2, exemplar quotation 2). Others viewed ACP more as an ongoing process that is best supported within an established patient-provider relationship (Table 2, exemplar quotation 3) and may even be impeded by a focus on task completion (Table 2, exemplar quotation 4).

Table 2.

Lack of a shared understanding and vision of advance care planning and its relationship with other aspects of care (theme 2)

| Exemplar Quotation No. | Source | Exemplar Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dialysis nurse | We have a kind of checkoff list, that when someone starts … they have to have PPDs, and one of them is we have to look at advance directive status, and if they don't have one filed … then initiate a discussion and then offer … [to] have the social worker or one of us come in and help them do that. |

| 2 | Social worker | I think it's best done one on one by someone, and it doesn’t have to be someone that they even know well, I think, if you normalize it. When I do discharge planning on inpatient units, I might meet somebody one time to do an assessment, and I always ask about advance directives. I think that explaining what the purpose is, why they are good to do, and why it’s a benefit to the person, all those things are important. |

| 3 | Social worker | I think it's hard sometimes … like for inpatients, the nurse would see there is no advance directive, and they would say that the patient wants to complete one … and we would go to talk to the patient, and the patient doesn’t even know what it is … and you don’t have a relationship with them to kind of influence them that way, in a sense persuading them that this is really a good thing to do. |

| 4 | Social worker | Advance directive completion is a process. You have to plant seeds along the way to get them to start to think about it … I just think it is something that it is hard to think about. It just introduces a lot of reality into your life, brings up your mortality, all of that. I think that it is kind of loaded, more so than what we can realize. It can be easy to just think, “Oh, it's just a document, what do you want?,” but these are huge decisions really. |

| 5 | Nephrologist | Well, the most common one really is the decision about whether, when and how to start maintenance dialysis for end stage renal disease and then, there is also the issue of DNR/DNI orders, but I actually don't address those commonly myself in clinic. Sometimes I do, but it is uncommon. It is more often the end stage renal disease questions. |

| 6 | Nephrologist | For DNR/DNI discussions for dialysis patients, my understanding is that our social worker and staff in the renal dialysis unit address that with everybody in the renal dialysis unit. For my chronic kidney disease patients, many of them have advance directives in the computer, not all of them do. I think those are coming in from primary care. |

| 7 | Nephrologist | I tend to think that my discussions with the patients … are important for them … I think I can give them the “big picture”; however, my time is limited, so … I always am able to give my opinion and allow them to ask some questions, but in the short period of time, it doesn't address everything. |

| 8 | Nephrologist | We actually, in dialysis, probably do a fair amount of it … we … constantly talk about whether people are going to want dialysis and their choices, including no treatment … especially with people … who have a lot of comorbidities, and we will talk about not having to do dialysis to extend life. So, I think it's emblematic of what advance care planning is … an ongoing conversation about patients’ goals and treatments. |

| 9 | Nephrologist | I think it's mostly that's what nephrologists do, whenever they start talking about dialysis and options … essentially, that's what they are doing, advance care planning … not everyone talks about … what happens without therapy or the mortality rate … so that may not happen. |

| 10 | Nephrologist | And that’s what most primary providers probably are faced with … it's just a huge number of scenarios that they can't go over. But I think, in nephrology, it's probably easier, the scenarios we are dealing with are a little bit more limited. |

| 11 | Nephrologist | If it's a patient whose been a long-term individual … whom I've followed for … several years, it's actually quite easy, because we've been talking about this here and there over the course of multiple different appointments. |

| 12 | Renal nurse | In general medicine and chronic progressive medical illnesses … nothing is an emergency, so you have the grace of time. It just has to be on your … clinical agenda. |

PPD, purified protein derivative; DNR/DNI, do not resuscitate/do not intubate.

Some nephrologists viewed ACP as a series of tasks that were largely separate from other elements of nephrology care (Table 2, exemplar quotation 5). One nephrologist drew a distinction between discussions about resuscitation—which he understood to be part of the dialysis consent process–and other aspects of ACP, such as advance directives (Table 2, exemplar quotation 6). He reported having some limited discussion with patients about the “big picture” but felt that his time was too “limited” to fully address ACP (Table 2, exemplar quotation 7).

Other nephrologists saw ACP as more integral to the care that they provided. One nephrologist described dialysis planning as “emblematic” of ACP (Table 2, exemplar quotation 8) but acknowledged that conversations about dialysis may not always extend to a detailed discussion of prognosis or alternatives to dialysis (Table 2, exemplar quotation 9). The more circumscribed nature of dialysis decision making was seen by some providers as advantageous in supporting discussions about ACP (Table 2, exemplar quotation 10). Nephrologists (Table 2, exemplar quotation 11) and other providers (Table 2, exemplar quotation 12) who viewed ACP as integral to their care tended not to view time as a constraint (“the grace of time”).

Theme 3: Unclear Locus of Responsibility and Authority for ACP

Not all providers felt responsible for conducting ACP with their patients; many felt that this was someone else’s job. Although some dialysis nurses embraced ACP as part of their role (Table 3, exemplar quotation 1), most dialysis unit staff did not consider this to be within their scope of practice (Table 3, exemplar quotation 2). A dietician felt that she could contribute to ACP but was uncertain whether she should be involved (Table 3, exemplar quotation 3). Some providers had a rigid understanding of sources of authority in completing discrete tasks related to ACP. Some nurses considered advance directives to be the domain of the social worker and did not feel authorized to complete this paperwork themselves (Table 3, exemplar quotation 4). One social worker believed that physicians and nurses were not technically authorized to complete an advance directive (Table 3, exemplar quotation 5). Although primary care physicians usually viewed ACP as their responsibility, some spoke of a reality in which tasks related to ACP fell to support staff because of time constraints (Table 3, exemplar quotation 6).

Table 3.

Unclear locus of responsibility and authority for advance care planning (theme 3)

| Exemplar Quotation No. | Source | Exemplar Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dialysis nurse | For a nurse, it's an opportune time, no matter where you work, to be able to talk to patients about it, but again, you have to … have some practice and knowledge about how to approach it, so it’s not going to be threatening to them. |

| 2 | Dialysis nurse | Myself, I don't work with patients in helping them with those types of decisions, because our social worker and the doctors work with patients on those. I know of it. I am well aware of it, but … I am not there to ask those questions. |

| 3 | Dietician | Is that the dietician’s role? Is that OK for me to bring up? It would definitely just depend on the patient and their relationship, and I don’t want to scare them, but … my role, that's always something I've wondered about. |

| 4 | Palliative care nurse | I think that one problem that I’ve had is that sometimes I just want the social worker; I can’t do an advance directive with a patient, because I’m a nurse and only the social worker can do that. |

| 5 | Social worker | Technically, the doctors are not supposed to be involved in advance care directives … There is a conflict, they cannot be a witness, and you know … I don't mean they can't do some educating, but I think the concern is that they are going to influence the patient … They can speak to the issues, but then, if you are actually helping them fill it out … it's kind of a slippery slope. Really, that's my understanding, because it says on the document that they don't want doctors and nurses being witnesses. And so, my assumption is that, you know, they shouldn't be helping them complete it. |

| 6 | Primary care provider | In the outpatient setting … there are these rules about patients being offered advance directives and given information. I must admit, it's often done more through social work and through the triage nurses doing the health promotions. |

| 7 | Nephrologist | You know, I'm sort of wondering whether somebody like a social worker or a psychologist may be very helpful to have for those kinds of appointments. |

| 8 | Nephrologist | And then … there are … issues … relating to DNR/DNI, and withdrawal of care, that's a common conversation. I am involved in that a lot less … It does come up sometimes, as a nephrologist, on the inpatient service. But I'm not really in the driver's seat. I don't consider myself in the driver's seat with that for the most part. |

| 9 | Primary care provider | Absolutely people should have something by the time they’re going to think about dialysis. That would be shockingly late in the course of things. |

| 10 | Primary care provider (responding to a question about who is involved in decisions about dialysis) | It’s usually really nephrology based, I think. I think sometimes I’m involved as a primary care physician if I’m really close to the patient. I can think of several patients that … I’ve talked to them a lot about it. Usually their spouses or significant others … the renal social workers are really good. I think they provide a lot of information. |

| 11 | Vascular surgeon | Well, I actually don't get engaged in those discussions, as a rule. Because the patients come to us specifically for dialysis access. And they are referred to us by the nephrologist, and I generally assume that the nephrologist and the patient have had a discussion about goals of care and decided that dialysis is an option for them. |

| 12 | Cardiologist | I presume they are very good with end-of-life care, at least in general, my colleagues that I work with, they certainly have been much more in tune than I have. I feel like … they are in good hands. I am less concerned than if they were going to see, oh, pulmonary or something like that. |

DNR/DNI, do not resuscitate/do not intubate.

Although nephrologists felt ownership of discussions related to dialysis initiation, they differed in how they viewed their role with respect to ACP (theme 2). Some considered this to be someone else’s responsibility but often, had only a vague notion of whose responsibility (Table 2, exemplar quotation 6 and Table 3, exemplar quotation 7). One nephrologist reported sometimes being involved in discussions about resuscitation in the inpatient setting but did not feel “in the driver’s seat” with those discussions (Table 3, exemplar quotation 8).

There was uniform agreement among non-nephrology providers that ACP should be addressed well in advance of dialysis initiation. A primary care provider commented that waiting until dialysis was initiated to complete ACP would be “shockingly late” (Table 3, exemplar quotation 9). Primary care providers and specialists outside nephrology often did not feel empowered—or did not see the need—to discuss dialysis initiation with their patients, because they believed this to be the responsibility of nephrology (Table 3, exemplar quotation 10). Providers outside nephrology tended to assume that nephrologists were conducting ACP as part of discussions about dialysis (Table 3, exemplar quotation 11) and even saw this as a strength of nephrology (Table 3, exemplar quotation 12).

Theme 4: Lack of Active Collaboration and Communication around ACP

There seemed to be little active collaboration or open communication around ACP among providers interviewed for this study. Completion of advance directives was recognized by dialysis unit staff as one of the functions of the multidisciplinary dialysis team after patients had initiated dialysis. However, neither completion of advance directives nor the broader process of ACP seemed to be a central function of this team, and only select team members were involved (Table 2, exemplar quotation 1 and Table 4, exemplar quotation 1).

Table 4.

Lack of active collaboration and communication around advance care planning (theme 4)

| Exemplar Quotation No. | Source | Exemplar Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dialysis nurse | Then we have a program when people start reaching stage 4 or 5, when they're [going to] need dialysis, that they come to education classes. And we have our staff, our dietician, social worker, transplant coordinator, all those people there, who talk to them about options, but also start planting the seeds about thinking about advance directives and what kind of care they might want to see. |

| 2 | Dialysis nurse | But some people have been a little bit harder than others to accept patient's decisions, sometimes. Like, for example, we have a couple of physicians that really encourage people up to the very end to continue, and maybe the patient is having a debilitating disease … it might not even be their renal disease, some other things going on that's making their quality of life really poor. But they kind of keep pushing on for them to have the dialysis. And sometimes the nursing staff, it might be difficult for them, because they see what's happening with the patients on a regular basis. |

| 3 | Dialysis nurse (responding to a question about what would have been helpful for patients to know earlier in the course of their kidney disease) | Um that it's a terminal disease! I hate to say that, but I don't think sometimes the physicians let them know that you know, I mean there's going to be an end point to this. And that at any point they can say “enough” or “stop.” I don't think the physicians … give them that knowledge. If they are feeling at some point their quality of life is poor, or they are not happy with what's going on, they can say “uncle.” |

| 4 | Dialysis nurse (describing her experience caring for a patient who wished to stop dialysis) | I really tried to advocate for that patient, to … help him feel support, because it probably felt to him like people were fighting him. And some of them weren’t. But, having met with the patient and dealt with him, we get to see him on a really regular basis, as nursing staff. Sometimes we do know a little bit more about their situation or how they are feeling and have discussions with them. So the physicians I think they sometimes look on this as a failure. They kind of keep pushing forth. |

| 5 | Dialysis nurse | With this kind of a chronic disease process and things that might happen, it's a good thing to … look at what options might be available for you later, if things progress or become worse, you know make your wishes known, so that somebody won't disrespect them. |

| 6 | Renal nurse | I think that, in nursing, we learn the power of communication. And learning how to meet people where they are at, to have a conversation with them, to try to help them … be as healthy can they can be or successful as they can be at whatever point in their life they are at with their medical illnesses, or whatever their challenges are. |

| 7 | Renal nurse | I would go back to communication … people are very sensitive to being spoken down to. I think it's really that literacy issue and understanding what kind of intellect this person is in possession of, so that you are speaking to them in a way that makes sense to them. That you use metaphors that make sense to them, that you are joining them in their experience at best you're able … not patronizingly … [but] out of good heart to try and be a better communicator. |

| 8 | Renal nurse | I think that, very commonly, the time when the clinician is ready to share the information has nothing to do with when the patient is ready to hear the information. That is the schism. You know I think it leads to all kinds of “well, I told them about this” … So, tell them again. Tell them a different way. Ask them to tell you what they just heard. Find out what they understood of what you just said. Because frequently, when people are freaked out … they hear the first word of every sentence. |

| 9 | Social worker | I know the doctors have a lot of patients to see, but I think that would take just a few moments, and if they didn't want to do it, I could certainly see that person at their first clinic appointment. But I've not been asked to do that. |

| 10 | Dialysis nurse | I think the majority of the time (about 60% of the time) it’s just the patient and I. I just talk, because I'm there! I talk with them. I've got 4 hours, they are captive! … And they talk and they talk, we review … What's been going on? How is it going? What are their goals they need to meet? |

| 11 | Dialysis nurse | I wish the nephrologist had a little bit more time. They try … but they just don't have much time. |

| 12 | Dialysis nurse | When to stop dialysis. It's so scary. I wish the nephrologists would come over and say, “This is what we can do for you.” Because some of them do want to really stop, but they are so scared … I'm not the right one to tell them meds their doc can give them … they are just so worried that they are going to drown. And I know it's not that way, and I try and tell them that … but they need reassurance from the nephrologist. |

Dialysis unit staff members were sometimes critical of nephrologists in terms of how they handled end-of-life decision making (Table 4, exemplar quotation 2). Dialysis nurses often felt that they had a better grasp of patients’ circumstances and priorities than the nephrologists and expressed concern that nephrologists were not open with patients about what to expect in terms of dialysis treatment and future illness trajectory (Table 4, exemplar quotation 3). Some nurses saw their role as patient advocate in situations where they felt that physicians were not upholding patients’ values (Table 4, exemplar quotation 4). Several dialysis staff members saw ACP as an opportunity for patients to protect themselves from the defaults in the system and the agendas of others (Table 4, exemplar quotation 5).

The comments of some providers spoke to a mismatch between assigned roles and the skills needed to promote ACP. Some nurses felt that their training—specifically in communication skills—made them especially well suited to engaging in discussions about ACP (Table 4, exemplar quotation 6). In general, nurses were more likely than physicians to reference the importance of communication skills (Table 4, exemplar quotation 7) and assessing patients’ readiness to engage in ACP (Table 4, exemplar quotation 8). A social worker saw her role as assisting patients with advance directives in the clinic if physicians did not have time but noted that she had not been “asked to do that” (Table 4, exemplar quotation 9). Some dialysis nurses felt that they had more time than physicians to talk with patients and understand their goals (Table 4, exemplar quotations 10 and 11). Nevertheless, dialysis nurses often felt that patients expected to hear information about prognosis and treatment options from their nephrologists, and they did not always feel authorized or qualified to enter into these conversations (Table 4, exemplar quotation 12).

Discussion

The value of a systematic approach to orchestrating the process of ACP for complex patients—who are typically cared for by multiple different providers in a range of settings during the course of illness—has received relatively little attention in the literature (30–32). The comments of providers who care for patients with advanced kidney disease interviewed for this study speak to the complex and fragmented patterns of care experienced by these patients and spotlight both the need for and the challenges to an interdisciplinary approach to ACP for this population.

Not all providers intuitively know how to work effectively as part of an interdisciplinary team (33–39), especially in a complex and fragmented care environment. This study identified almost all facets of effective interdisciplinary collaboration as potential targets for intervention in efforts to enhance ACP for patients with advanced kidney disease (31,34–48). First, although most providers interviewed seemed to appreciate the potential value of ACP for patients with advanced kidney disease, they did not share a common vision or understanding of ACP and its relationship with other aspects of care, such as dialysis decision making. These findings are consistent with reports of differing conceptualizations of ACP among oncology nurses, community nurses, and primary care providers (49–51). Second, team membership and roles were poorly delineated, and lines of authority and accountability for ACP were unclear. ACP was often perceived as someone else’s responsibility. These findings resonate with reports of uncertainty about the locus of responsibility for ACP among palliative care physicians and generalists caring for patients in the hospital (52–54) and among providers caring for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (55). Third, relationships between different providers caring for the same patients were not always characterized by a spirit of collaboration and open communication. Providers often had difficulty understanding the roles and challenges of their colleagues caring for the same patients at different points along the illness trajectory or in different settings. Lack of collaboration and communication around ACP across providers and settings has been previously reported among oncology nurses (49,56) and among VA providers (51). Fourth, many providers seemed to feel that their skills were underutilized. Similar to earlier reports among oncology (49,56), nephrology (18), and intensive care unit nurses (32), some providers interviewed for this study did not feel authorized or qualified to shape the process of ACP for individual patients, despite having relevant experience, background, and/or training.

For patients with a dominant health condition, grounding discussions about ACP in situations and treatment decisions with unique relevance to that condition can offer powerful opportunities for synergy with ongoing disease management (57–59). A disease-specific approach to ACP may hold particular promise for patients with advanced kidney disease. Dialysis is often initiated in the acute setting and is among the intensive procedures that may be listed in an advance directive (60,61). Indeed, many of the providers interviewed for this study tended to default to discussing dialysis initiation and/or discontinuation when asked about ACP. Although it seemed self-evident to many providers (especially those outside nephrology) that patients should have an opportunity to engage in ACP before dialysis initiation, fragmentation of care seemed to conspire against this ideal. Primary care providers felt responsible for conducting ACP but did not typically engage in discussions about dialysis, whereas the opposite was often true for nephrologists. Taken together, these findings suggest that a primary care–based approach to ACP—as currently implemented in the VA (62) and elsewhere—may result in missed opportunities for synergy with specialized treatment decisions such as dialysis initiation and discontinuation.

System-level problems often call for system-level solutions. Based on insights gained from providers interviewed for this study, we suspect that systematic efforts to promote interdisciplinary collaboration at a variety of organizational levels beyond that of the individual provider will be needed to support ACP in this population (36,38,39). Interventions to promote effective teamwork around ACP might include strategies to define team membership, roles, and lines of accountability to clarify which providers have primary responsibility for conducting ACP with individual patients and how other providers might support this process. It will also be important to build a common understanding and vision of ACP among providers caring for the same patients; leverage the unique strengths of individual providers; and foster trust, empathy, mutual respect, and open communication among team members.

The single-center design of our study is both a strength and a limitation. The findings described here are all the more striking for having emerged from interviews with a small number of providers caring for the same group of patients at a single medical center. Themes related to shared vision, role delineation, and collaboration around ACP also resonate with published work in other settings and populations, supporting the broader relevance of our findings (18,32,49–56). Nevertheless, our study does not provide information on how ACP for patients with advanced kidney disease is approached at other centers within or outside the VA.

In conclusion, complexity and fragmentation of medical care across settings and providers and over time for patients with advanced kidney disease pose a significant challenge to orchestrating the process of ACP among members of this population. Systematic efforts to promote interdisciplinary collaboration among the diverse providers who care for patients with advanced kidney disease will likely be needed to promote effective ACP in this population.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Whitney Showalter for administrative support for this project and Drs. Susan Crowley (VA Renal Program Director and Nephrology Section Chief at the West Haven VA) and Robert Pearlman (Chief of Ethics Evaluation at the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care and Staff Physician at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System) for supporting this project. We also thank the providers at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System who participated in this study.

This work was supported by VA Health Services Research and Development grant VA IIR 12-126 (principal investigator A.M.O). R.T. was supported by VA Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award CDA-09-206 (principal investigator R.T.).

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study, including collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of VA or the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “The Provider’s Role in Conservative Care and Advance Care Planning for Patients with ESRD,” on pages 750–752.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.11351015/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sudore RL, Fried TR: Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: Preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med 153: 256–261, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer PA, Martin DK, Lavery JV, Thiel EC, Kelner M, Mendelssohn DC: Reconceptualizing advance care planning from the patient’s perspective. Arch Intern Med 158: 879–884, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holley JL, Davison SN: Advance care planning in CKD: Clinical and research opportunities. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 739–740, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel UD, Schulman KA: Invited commentary—can we begin with the end in mind? End-of-life care preferences before long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 663–664, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holley JL, Davison SN: Advance care planning for patients with advanced CKD: A need to move forward. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 344–346, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, Jha V, Brown EA, Brennan F, Murtagh FE, Naicker S, Germain MJ, O’Donoghue DJ, Morton RL, Obrador GT: Executive summary of the KDIGO Controversies Conference on Supportive Care in Chronic Kidney Disease: Developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney Int 88: 447–459, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurella Tamura M, Goldstein MK, Pérez-Stable EJ: Preferences for dialysis withdrawal and engagement in advance care planning within a diverse sample of dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 237–242, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, Cohen RA, Waikar SS, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP: Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1206–1214, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray AM, Arko C, Chen SC, Gilbertson DT, Moss AH: Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1248–1255, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, Briggs LA, Brown RL: Effect of a disease-specific planning intervention on surrogate understanding of patient goals for future medical treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 58: 1233–1240, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song MK, Ward SE, Fine JP, Hanson LC, Lin FC, Hladik GA, Hamilton JB, Bridgman JC: Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: A randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 813–822, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davison SN, Kromm SK, Currie GR: Patient and health professional preferences for organ allocation and procurement, end-of-life care and organization of care for patients with chronic kidney disease using a discrete choice experiment. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 2334–2341, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davison SN, Simpson C: Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: Qualitative interview study. BMJ 333: 886, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fine A, Fontaine B, Kraushar MM, Plamondon J: Patients with chronic kidney disease stages 3 and 4 demand survival information on dialysis. Perit Dial Int 27: 589–591, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fine A, Fontaine B, Kraushar MM, Rich BR: Nephrologists should voluntarily divulge survival data to potential dialysis patients: A questionnaire study. Perit Dial Int 25: 269–273, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orsino A, Cameron JI, Seidl M, Mendelssohn D, Stewart DE: Medical decision-making and information needs in end-stage renal disease patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 25: 324–331, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ceccarelli CM, Castner D, Haras MS: Advance care planning for patients with chronic kidney disease--why aren’t nurses more involved? Nephrol Nurs J 35: 553–557, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perry E, Swartz R, Smith-Wheelock L, Westbrook J, Buck C: Why is it difficult for staff to discuss advance directives with chronic dialysis patients? J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2160–2168, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egan R, Macleod R, Tiatia R, Wood S, Mountier J, Walker R: Spiritual care and kidney disease in NZ: A qualitative study with New Zealand renal specialists. Nephrology (Carlton) 19: 708–713, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yee A, Seow YY, Tan SH, Goh C, Qu L, Lee G: What do renal health-care professionals in Singapore think of advance care planning for patients with end-stage renal disease? Nephrology (Carlton) 16: 232–238, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schell JO, Patel UD, Steinhauser KE, Ammarell N, Tulsky JA: Discussions of the kidney disease trajectory by elderly patients and nephrologists: A qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 495–503, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Holley JL, Moss AH: Nephrologists’ reported preparedness for end-of-life decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1256–1262, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holley JL, Davison SN, Moss AH: Nephrologists’ changing practices in reported end-of-life decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 107–111, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Schols JM, van der Sande FM, Frenken LA, Wouters EF: Insight into advance care planning for patients on dialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 45: 104–113, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glaser BG, Strauss AL: The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, New Brunswick, NJ, Transaction Publishers, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strauss AL, Corbin J: Basics of Qualitative Research: Procedures and Techniques for Developing Grounded Theory, Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plano Clark VL: CJW. The Mixed Methods Reader, Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morse JM: Sampling in grounded theory. In: The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory, edited by Bryant A, Charmaz K, Los Angeles, Sage, 2010 (paperback edition), pp 229–244

- 30.Ahluwalia SC, Bekelman DB, Huynh AK, Prendergast TJ, Shreve S, Lorenz KA: Barriers and strategies to an iterative model of advance care planning communication. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 32: 817–823, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Wilkinson A, Mularski RA, Morton SC, Hughes RG, Hilton LK, Maglione M, Rhodes SL, Rolon C, Sun VC, Shekelle PG: Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med 148: 147–159, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milic MM, Puntillo K, Turner K, Joseph D, Peters N, Ryan R, Schuster C, Winfree H, Cimino J, Anderson WG: Communicating with patients’ families and physicians about prognosis and goals of care. Am J Crit Care 24: e56–e64, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi BC, Pak AW: Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clin Invest Med 29: 351–364, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi BC, Pak AW: Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 2. Promotors, barriers, and strategies of enhancement. Clin Invest Med 30: E224–E232, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi BC, Pak AW: Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 3. Discipline, inter-discipline distance, and selection of discipline. Clin Invest Med 31: E41–E48, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altilio T, Dahlin C, Remke SS, Tucker R, Weissman DE: Strategies for Maximizing the Health/Function of Palliative Care Teams, New York, Center to Advance Palliative Care, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mosher HJ, Kaboli PJ: Inpatient interdisciplinary care: Can the goose lay some golden eggs? JAMA Intern Med 175: 1298–1300, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xyrichis A, Ream E: Teamwork: A concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 61: 232–241, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xyrichis A, Lowton K: What fosters or prevents interprofessional teamworking in primary and community care? A literature review. Int J Nurs Stud 45: 140–153, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medicine Io : To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medicine Io : Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Medicine Io : Keeping Patients Safe, Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chaboyer WP, Patterson E: Australian hospital generalist and critical care nurses’ perceptions of doctor-nurse collaboration. Nurs Health Sci 3: 73–79, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaefer HG, Helmreich RL, Scheidegger D: Human factors and safety in emergency medicine. Resuscitation 28: 221–225, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haugen AS, Søfteland E, Almeland SK, Sevdalis N, Vonen B, Eide GE, Nortvedt MW, Harthug S: Effect of the World Health Organization checklist on patient outcomes: A stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 261: 821–828, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bergs J, Hellings J, Cleemput I, Zurel Ö, De Troyer V, Van Hiel M, Demeere JL, Claeys D, Vandijck D: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of the World Health Organization surgical safety checklist on postoperative complications. Br J Surg 101: 150–158, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gillespie BM, Chaboyer W, Thalib L, John M, Fairweather N, Slater K: Effect of using a safety checklist on patient complications after surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 120: 1380–1389, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, Sinopoli D, Chu H, Cosgrove S, Sexton B, Hyzy R, Welsh R, Roth G, Bander J, Kepros J, Goeschel C: An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med 355: 2725–2732, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jezewski MA, Meeker MA, Schrader M: Voices of oncology nurses: What is needed to assist patients with advance directives. Cancer Nurs 26: 105–112, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seymour J, Almack K, Kennedy S: Implementing advance care planning: A qualitative study of community nurses’ views and experiences. BMC Palliat Care 9: 4, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahluwalia SC, Levin JR, Lorenz KA, Gordon HS: Missed opportunities for advance care planning communication during outpatient clinic visits. J Gen Intern Med 27: 445–451, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gardiner C, Cobb M, Gott M, Ingleton C: Barriers to providing palliative care for older people in acute hospitals. Age Ageing 40: 233–238, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C: Factors supporting good partnership working between generalist and specialist palliative care services: A systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 62: e353–e362, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gott M, Seymour J, Ingleton C, Gardiner C, Bellamy G: ‘That’s part of everybody’s job’: The perspectives of health care staff in England and New Zealand on the meaning and remit of palliative care. Palliat Med 26: 232–241, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gott M, Gardiner C, Small N, Payne S, Seamark D, Barnes S, Halpin D, Ruse C: Barriers to advance care planning in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Palliat Med 23: 642–648, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jezewski MA, Brown J, Wu YW, Meeker MA, Feng JY, Bu X: Oncology nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences regarding advance directives. Oncol Nurs Forum 32: 319–327, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schellinger S, Sidebottom A, Briggs L: Disease specific advance care planning for heart failure patients: Implementation in a large health system. J Palliat Med 14: 1224–1230, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, Briggs LA, Brown RL: Effect of a disease-specific advance care planning intervention on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 60: 946–950, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Benditt JO, Smith TS, Tonelli MR: Empowering the individual with ALS at the end-of-life: Disease-specific advance care planning. Muscle Nerve 24: 1706–1709, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Hare AM, Wong SP, Yu MK, Wynar B, Perkins M, Liu CF, Lemon JM, Hebert PL: Trends in the timing and clinical context of maintenance dialysis initiation. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 1975–1981, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Healthcare intensity at initiation of chronic dialysis among older adults. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 143–149, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Department of Veterans Affairs VHA : Advance Care Planning and Management of Advance Directives. VHA Handbook, Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, 2013, pp 1–17 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.