Abstract

Type 3 Diabetes (T3D) is a neuroendocrine disorder that represents the progression of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) to Alzheimer’s disease (AD). T3D contributes in the increase of the total load of Alzheimer’s patients worldwide. The protein network based strategies were used for the analysis of protein interactions and hypothesis was derived describing the possible routes of communications among proteins. The hypothesis provides the insight on the probable mechanism of the disease progression for T3D. The current study also suggests that insulin degrading enzyme (IDE) could be the major player which holds the capacity to shift T2DM to T3D by altering metabolic pathways like regulation of beta-cell development, negative regulation of PI3K/AKT pathways and amyloid beta degradation.

Insulin signaling pathways are conserved in various types of cells and tissues. It regulates the energy metabolism, homeostasis and reproduction in living system. It reaches the brain via cerebral spinal fluid and transporters present at the blood brain barrier. It is proposed to enhance cognitive abilities via activation of insulin receptors in the hippocampal region of brain. It stimulates translocation of GLUT4 to hippocampal plasma membranes thereby enhancing the glucose uptake in the time dependent manner1. Glucose utilization during neuronal activity is similar in both peripheral tissue and hippocampal region1. Scientists have worked extensively to understand the molecular mechanisms involved in the production and secretion of insulin in the brain and pancreas2. Their findings suggest that both beta cells and neurons respond to glucose and hormonal stimuli by depolarization of ATP sensitive potassium channels in similar fashion. Few studies report that insulin was stored in synaptic vesicles at nerve endings in rat brain and was released under depolarization conditions2. The study also suggests that insulin secretion in synaptosomes is increased by glucose and addition of glycolytic inhibitor resulted in 50% decrease in glucose-induced release of immunoreactive insulin2. Hence the process of glucose metabolism is similar in brain and pancreas and the brain itself might synthesize some portion of the insulin2.

The binding of insulin to its receptor leads to cascades of intracellular signaling which activates the Insulin Receptor Substrate-1(IRS1), extracellular signal-related kinase/mitogen -activated protein kinase (ERK/MAPK), and PI3kinase/AKT pathways (PI3K/AKT) followed by inhibition or suppression of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3)2. Disturbances to these pathways can lead to complication like cardiovascular diseases, pancreatic cancer, neuropathy, nephropathy etc2. It also adds to several other issues like mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and dysregulated metabolic profiles2.

There is an exponential increase in the prevalence of T2DM cases worldwide and it is likely to reach 592 million by 20353. Also the incidences of T2DM induced AD is rapidly increasing in human population in last few years4. T2DM patients have almost double the chances of developing AD in comparison to the patients that have only insulin resistance5. Therefore, T3D is also adding to the already existing burden of AD in the society.

T2DM and AD patients have similar amyloid beta deposits both in pancreas as in the brain6. Several researchers have suggested this new pathology to be addressed as Type 3 Diabetes (T3D)4,5,6,7. Some of the target receptors of T2DM such as IGF-1R, PPARG and IDE are also involved in the regulation of the expression and phosphorylation of tau protein7. It is intriguing to observe that both hyperinsulinaemia and IDE are related to the risk of AD and is independent of APOE4 gene7. Hence T2DM induced AD is believed to be sporadic irrespective of presence of heterozygous or homozygous conditions of ApoE2,7.

Seventy susceptible genes are associated with T2DM at a genome-wide level8. Some of the polymorphic genes associated with T2DM are PPARG, KCNJ11, TCF7L2, HHEX/IDE, CDKAL1, SLC30A8, IRS1, INSR etc8.

In the current study, we report for the first time an ideal hypothesis relating possible protein-protein interactions that might be taken up by the system during the progression of T2DM induced AD. It also predicts candidate/s for developing drugs that can target both pathological conditions.

Results

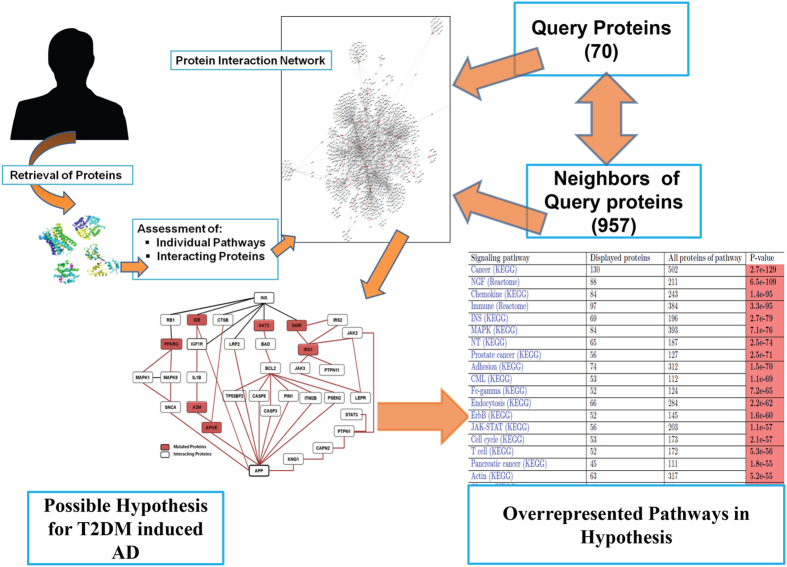

Few differentially regulated proteins of T2DM and AD were collected after extensive literature mining (Supplementary Table 1). The proteins were queried on Pathwaylinker2.0 and the interactions were displayed as balls and sticks. Balls are the queried proteins and sticks represent the interactions between them, both theoretical and experimental (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Interactions between differentially expressed proteins of AD and T2DM.

The figure shows the methodology of work done. It correlates the differentially expressed proteins of Type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. The table represents the majorly involved pathways in T3D pathology and ranked according to their predicted P-values.

These interactions indicate the cross talk between proteins. This is either due to their participation in similar pathways or because of their intermittent and short lived interactions in some processes. The connections were also established on the basis of the shared protein partners.

A total of 957 interacting proteins were retrieved for 70 query proteins. Entire subset of 1027 proteins was analyzed for overrepresented and shared pathways. The biasedness of the data was calculated statistically by examining P-values. For example 196 proteins are involved in Insulin (INS) Pathway (HPRD, STRING, BioGrid) (Table 1) and in the dataset of 1027 proteins only 69 proteins are involved in INS Pathway. The probability of coming INS pathway in our dataset is 2.7e79 which means INS pathway is among the most followed pathway by both query and neighbor proteins. Similarly the probability of occurrence of Alzheimer’s and Diabetes II pathways in our dataset is 6.6e-41 and 6.9e-35 respectively.

Table 1. List of Pathways followed by total queried proteins and their first neighbors.

| Signaling Pathway | Displayed Proteins (A) | All proteins of Pathway (B) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemokine(KEGG) | 84 | 243 | 1.4e-95 |

| Immune (Reactome) | 97 | 384 | 3.3e-95 |

| INS (KEGG) | 69 | 196 | 2.7e-79 |

| MAPK(KEGG) | 84 | 393 | 7.1e-76 |

| Cell Cycle(KEGG) | 53 | 173 | 2.1e-57 |

| JAK-STAT(KEGG) | 56 | 203 | 1.1e-57 |

| PancreaticCancer(KEGG) | 45 | 111 | 1.8e-55 |

| T cell (KEGG) | 52 | 172 | 5.3e-56 |

| Cytokine (KEGG) | 62 | 323 | 3.6e-53 |

| Fc-epsilon (KEGG) | 41 | 101 | 1.1e-50 |

| Apoptosis (KEGG) | 42 | 134 | 3.1e-46 |

| P53 (KEGG) | 35 | 93 | 4.8e-42 |

| Alzheimer (KEGG) | 46 | 227 | 6.6e-41 |

| Diabetes II (KEGG) | 29 | 78 | 6.9e-35 |

| SCLC(KEGG) | 38 | 128 | 6.2e-41 |

It was seen that Chemokine (AKT1 [P31749]; AKT2 [P31751]; CCL4 [P13236]), Immune (CD4 [P01730]; VCAM1 [P19320]; PTPN11 [Q06124]), INS (INSR [P06213]; INS [P01308]; IRS1 [P35568]) MAPK (MAPK1 [P28482]; MAPK8 [P45983]; EGFR [P00533]), Cell cycle (YWHAZ [P63104]; RB1 [P06400]; GSK3B [P49841]), JAK-STAT (JAK2 [O60674] ; JAK3 [P52333] ; STAT3 [P40763]), Pancreatic Cancer (BAD [Q92934]; MAPK8 [P45983]; STAT3 [P40763]), T-Cell (GSK3B [P49841]); PIK3R3 [Q92569]; JUN [P05412]), Fc-epsilon (IL4 [P05112]; RAF1 [P04049]; GRB2 [P62993]), P53 (IGF1 [P05019]; CDK4 [P11802]; BAX [Q07812]), Alzheimer (APP [P05067]; IDE [P14735]; BACE2 [Q9Y5Z0]), Apoptosis (BCL2 [P10415]; IL1B [P01584]; CASP8 [Q14790]) and SCLC (BCL2 [P10415]; E2F1 [Q01094]; CDK6 [Q00534]) were some of the overrepresented signaling pathways with their P-values (Table 1). Hence the sub-pathways and the other processes under these Super-Pathways are predicted to take place in the Type 3 pathology (Supplementary Table 2).

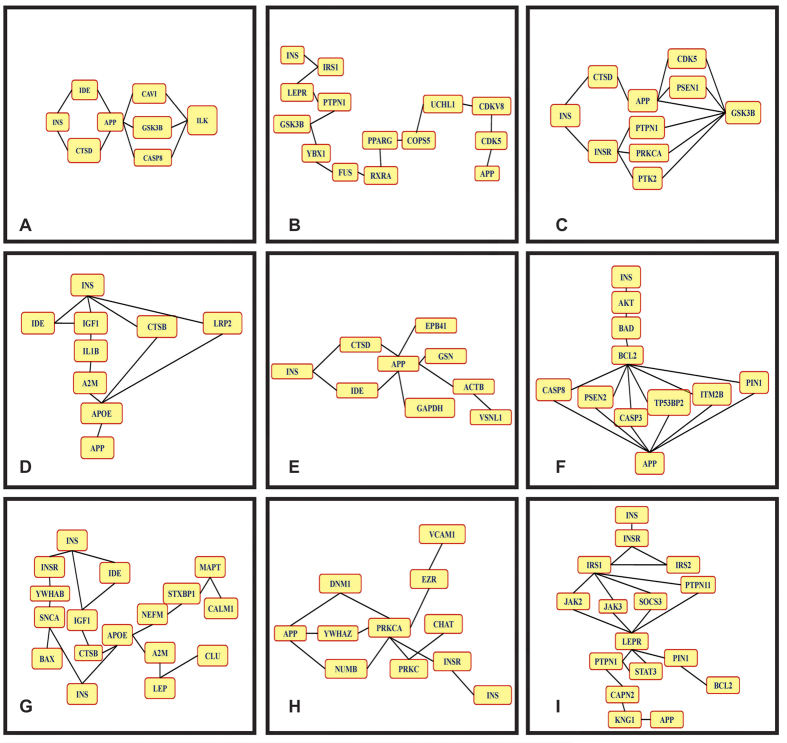

Table 1 represents A (Query proteins) and B (Proteins involved in the specific pathways as per databases like STRING, HPRD and BIOGRID). Several hypotheses were framed by using the interacting proteins data. These small interactions depict the probable routes through which insulin resistance might lead to amyloid plaque formation in brain. These interactions indirectly or directly affect each other’s function and contribute in disease pathology (Fig. 2A–I).

Figure 2. Schematic Representation of different protein interactions involved in T2DM induced AD.

The figure shows the different hypothesis of progression of T3D. These short interactions depict the mechanism through which insulin and amyloid beta are linked.

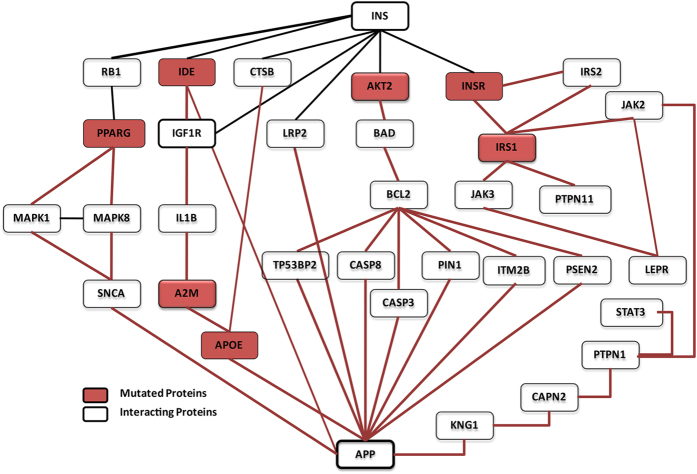

For the identification of potential druggable targets a common hypothesis was designed for both nearest and distant interacting partners. This hypothesis contains seven possible routes of progression of T2DM to AD. The role/function of proteins in hypothesis (Figs 3 and 4) is discussed below:

Figure 3. Interaction of selected proteins from the network supposedly followed in T3D (mutated proteins are highlighted in red).

Final protein- interaction network was framed which includes mutated and differentially expressed proteins which link Type 2 Diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease.

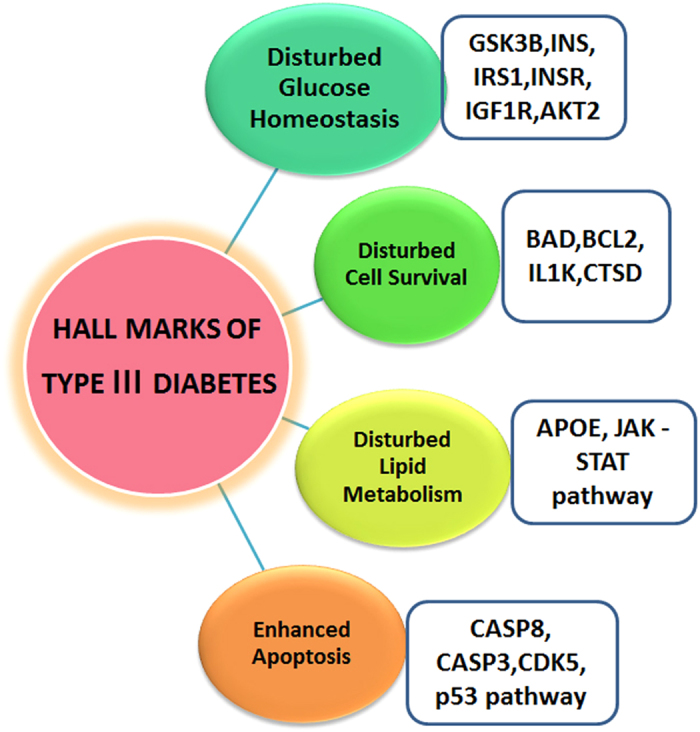

Figure 4. Hallmarks of Type 3 Diabetes.

Attributes of Type 3 Diabetes represents the disturbed metabolic processes and pathways in Type 3 diabetes.

Route I

Diabetes is the result of impaired insulin signal transduction which up regulates the activity of IDE9,10. IDE degrade both insulin and amylin in a dose dependent manner11. It is proposed here that since IDE is elevated in both T2DM and AD, its increased levels degrade insulin10. The elevated expression of IDE downregulates insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1) which further increases the activity of interleukin 1 beta (IL1B)12,13. Excess of interleukins produces oxidative stress in the brain. Various studies report that IL1B forms a complex with alpha- 2-microglobulin (A2M)14,15 which controls the activity of apolipoprotein E (APOE) involved in the formation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and hence contributes in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease16.

Route II

It is proposed that the insulin resistance causes disturbances in insulin signaling pathway which retains RAC-beta serine/threonine-protein kinase (AKT)17 in dephosphorylated state followed by de-phosphorylation of Bcl2-associated agonist of cell death (BAD)18. Dephosphorylation causes BAD to initiate apoptosis process19. The BAD protein plays key role in both diabetes and AD pathology. In T2DM the dephosphorylated BAD upregulates BCl2 and causes cell death. Similarly in AD, dephosphorylated BAD protein causes mitochondrial dysfunction20 thereby inducing apoptosis through Apoptosis regulator Bcl-2 (BCL2) mediated proteins such as CASP321,22, CASP823,24, PSEN125,26, PIN127,28, TP53BP229,30, ITM2B31,32 and results in APP formation that contributes in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease in the early stage.

Route III

Cathepsin B (CTSB) is involved in the conversion of proinsulin to insulin33. It is proposed that the insulin resistance causes down regulation of CTSB protein and hence disturbs the insulin balance in the system. The CTSB protein further interacts with APOE and up regulates it34. Increased APOE expression results in APP formation and hence also contributes in AD pathology.

Route IV

Low density lipoprotein 2(LRP2) proteins helps in the retention of insulin from kidney during clearance of other substances (termed as clearance pathway)35. It is proposed that the decreased insulin signal causes decreased expression of LRP2 and hence eventually up regulates the expression of APOE thereby participating in AD pathology36.

Route V

Retinoblastoma protein (RB) has been shown to facilitate adipocyte differentiation by forming a complex with insulin37,38. It is proposed that the Insulin resistance inhibits this complex formation, which in turn affects the RB protein. This RB protein further prevents PPARG from inhibition39. PPARG activation is linked with MAPK signaling pathway, up regulation of former results in decrease activity of Mitogen activated protein kinases1 (MAPK1) and Mitogen activated protein kinase 8 (MAPK8)40. The decreased activity of MAPK pathway affects the alpha synuclein (SNCA)41 and this SNCA interacts with amyloid beta and contributes in AD42.

Route VI

It is proposed that the impairment in the insulin signaling reduces the affinity of insulin for Insulin receptor (INSR)43. INSR interacts with Insulin receptor substrate1(IRS1) and Insulin receptor substrate2 (IRS2), although the nature of interaction between the two has not been understood yet44,45. Changes in activity of IRS2 affect IRS146. Further IRS1 affects regulatory receptor for fat metabolism i.e. leptin receptor (LEPR) through JAK347,48, SOCS349,50, JAK251,52 and PTPN1153,54 and LEPR protein interacts with PIN155. PIN1 in turn regulates the amyloid-β production28.

Route VII

It is proposed that the interaction of PTPN1 with LEPR is indirect through JAK256,34 and STAT357,34. In some studies PTPN1 is also involved in formation of APP via CAPN258 followed by KNG159,60 signaling. It was also seen that impaired signals of IRS1 are directly involved in the progression of AD via BCL-2 protein.

From the above mentioned hypotheses, the closest and most appropriate route for progression of T2DM to AD is Route I. This route was chosen because it has those proteins which are directly involved in pathogenesis of both T2DM and AD respectively. Insulin resistance ultimately leads to destruction of beta-cells of pancreas4. Therefore in the later stages of diabetes mellitus, the levels of insulin in the body start depleting4. Decreased insulin concentrations cause defects in cognition, memory and learning abilities of an individual similar to Alzheimer’s patients. On the other hand, in diseased condition the overproduced amylin reaches the brain via blood brain barrier and form plaques similar to amyloid beta. The deposition of amylin in brain blood vessels is responsible for the building of other amylin amyloid plaques and hence increases the risk of AD. These deposits were also seen in the brain tissue of older people who had diabetes and vascular dementia. In hyperinsulinemic condition, the variation of IDE results in the degradation of insulin rather than amyloid beta10,13. Therefore two events make this pathology worse, first is excessive degradation of insulin due to overexpression of IDE in T2DM which in turn accounts for lesser levels of insulin in brain and secondly, the inefficient clearance of ABeta in the brain by IDE10,13.

Discussion

The study deciphered the series of interactions which may possibly happen during the pathology of T3D. Out of the seven possible routes of the progression of disease the most appropriate is the one which initiates with the signal transduction through IDE receptor. As mentioned in route 1 the transmission of impaired insulin signal upregulates IDE and increases its activity12. Alternatively there are studies which report that IDE is mutated in T2DM10. It is very likely that any mutations in IDE changes its function and disturbs various signaling processes (Supplementary table 2) and these disturbances can contribute to T3D pathology.

Increased IDE activity causes more degradation of insulin than the normal conditions13. Some studies reported that glucose utilization by brain is independent of insulin but on the contrary Ren et al.1 have confirmed that GLUT 4 constitutes a subset of neurons in hippocampal region which are insulin sensitive. Uptake of the glucose through these receptors might play an important role in the cognition and hippocampal based learning1. IDE inhibitors can be a good therapeutic intervention to stop these chains of events at this level11. Uncontrolled IDE activity further downregulates IGF-1R protein expression12. IGF-1R is important for synaptic transfer and plasticity. Its downregulation will lead to neuronal damage. According to the study of Westwood et al.9, IGF-1R downregulation in brain causes formation of oligomers and cognitive impairment which increases the chances of developing Alzheimer’s disease in a diabetic patient. Higher expression of IGF-1R also contributes in development of AD in older people. Therefore both the upregulation and downregulation of IGF-1R affects brain. Though IGF-1R is a druggable target, therapies based on the growth factor failed in clinical trials. Improvisations in these drugs are still awaited. IGF-1R may further activate interleukins and creates excessive oxidative stress in the brain tissue13. Oxidative stress is already implicated as one of the factors for deposition of amyloid beta in brain.

The study of Maedler et al.15 reported that disturbed IL1B signals are involved in the progression of insulin resistance and leads to T2DM. These activated interleukins and alpha-2-microglobuin then forms a complex and eventually upregulates the expression of APOE16. Therapies like anti-APOE antibody are already under clinical trials for decreasing amyloid beta load in the AD brain.

Drug discovery groups have a wide-spread understanding now that the incurable diseases have multiple molecular targets. Hence drugs directed to single molecular target (conventional old drugs) are insufficient. To accomplish this objective one can either target multiple molecular targets at the same time using different combinations of drug or use one drug which controls multiple targets. Both the approaches are equally achievable from the clinical perspective.

In the past many multi target drugs have been proposed for both T2DM and AD respectively. Till date there are no drugs available for Type 3 Diabetes as no receptor has been worked out so far. Therefore the present study concludes that proteins involved in Route 1 may provide some insight into the mechanism of the disease. Identified major proteins i.e. IDE, IGF-1R, IL1B, A2M and APOE can be targeted simultaneously or individually to target this disease. Since these events start with dysregulations of signals at IDE level, it is proposed that IDE should be the favored target and could be an answer to this incurable disease.

Methods

Development of a local protein database for Network Assessment

Extensive literature mining was done to retrieve the list of proteins which are differentially regulated in T2DM and AD. Accession numbers of all the proteins were retrieved from UniprotKB (http://www.uniprot.org/) and stored in a local database (Supplementary Table 1). These proteins were checked with Gene Ontology Databases for their involvement in different metabolic processes.

Generation of Protein- protein interaction Network

Retrieved proteins were queried with different databases like HPRD, BioGrid and STRING which contains information of experimentally validated protein- protein interactions identified by different biochemical assays. This will generate the list of protein interactors to these query proteins. The total subset of proteins was analyzed by Pathwaylinker2.0 (http://pathwaylinker.org/). It creates a master network among the queried proteins and their neighbors. This network was checked for the pathways mostly followed by total subset of 70 query as well as their neighbor proteins. This results in the list of pathways along with their P-values (Probability value). P-values ensured that the results were independent of each other. The selection of query proteins of both T2DM and AD was done randomly without the prior knowledge about their shared processes and pathways.

Framing and analysis of Hypothesis

The complex master network was segregated into nine short interactions to understand the relationship between the queries and their neighboring partners. These interactions were merged keeping insulin as the starting point of the hypothesis which culminates at APP. Interacting neighbor proteins were chosen from the master network and added to the hypothesis in step-wise manner. The final hypothesis was created and explains the events that the system undertakes to shift from insulin resistance to formation of amyloid beta plaques.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Mittal, K. et al. Type 3 Diabetes: Cross Talk between Differentially Regulated Proteins of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Alzheimer's Disease. Sci. Rep. 6, 25589; doi: 10.1038/srep25589 (2016).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Ashok K. Chauhan, Founder President, Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Noida for providing the infrastructure and support.

Footnotes

Author Contributions D.P.K. has given the concept of interactions between the two pathologies and finalization of manuscript. K.M. and R.J.M. have contributed to interaction analysis and in the preparation of manuscript.

References

- Ren H. et al. Glut4 expression defines an insulin-sensitive hypothalamic neuronal population. Mol Metab. 3, 452–459 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez E., Velázquez E., Hurtado-Carneiro V. & Ruiz-Albusac J. M. Insulin in the brain: its pathophysiological implications for states related with central insulin resistance, type2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Endocrinol. 5, 3389 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guariguata L. et al. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 103, 137–149 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biessels G. J., Strachan M. W., Visseren F. L., Kappelle L. J. & Whitmer R. A. Dementia and cognitive decline in type 2 diabetes and prediabetic stages: towards targeted interventions. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2, 246–255 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot K. et al. Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline. J Clin Invest. 122, 1316–1338 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroner Z. The relationship between Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes: type 3 diabetes. Altern Med Rev. 14, 373 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzanne M. Type 3 diabetes is sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: Mini-review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 24, 1954–1960 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Yu W. & Hu C. Genetics of type 2 diabetes : insights into the pathogenesis and its clinical application. Biomed Res Int, doi: 10.1155/2014/926713 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedse G., Di Domenico F., Serviddio G. & Cassano T. Aberrant insulin signaling in Alzheimer’s disease: current knowledge. Front Neurosci, doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00204 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Joachimiak A., Rosner M. R. & Tang W. J. Structures of human insulin-degrading enzyme reveal a new substrate recognition mechanism. Nature. 443, 870–874 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. J. Targeting Insulin-Degrading Enzyme to Treat Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 27, 24–34 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L., Becker A. B., Suzuki A. & Roth R. A. Comparison of the enzymatic and biochemical properties of human insulin-degrading enzyme and Escherichia coli protease III. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 2414–2420 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T., Wang D. E. L. I., Nagpal M. L., Chang W. E. I. W. E. I. & Calkins J. H. Down-regulation of Leydig cell insulin-like growth factor-I gene expression by interleukin-1. Endocrinology. 130, 1217–1224 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb D. J. & Gonias S. L. A modified human alpha 2-macroglobulin derivative that binds tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 beta with high affinity in vitro and reverses lipopolysaccharide toxicity in vivo in mice. Lab Invest. 78, 939–948 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maedler K., Dharmadhikari G., Schumann D. M. & Størling J. Interleukin-1 beta targeted therapy for type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 9, 1177–1188 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krimbou L., Tremblay M., Davignon J. & Cohn J. S. Association of apolipoprotein E with α 2-macroglobulin in human plasma. J. Lipid Res. 39, 2373–2386 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teruel T., Hernandez R. & Lorenzo M. Ceramide mediates insulin resistance by tumor necrosis factor-α in brown adipocytes by maintaining Akt in an inactive dephosphorylated state. Diabetes. 50, 2563–2571 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies R. J., Robey I. & Gatenby R. A. Causes and consequences of increased glucose metabolism of cancers. J. Nucl. Med. 49, 24S–42S (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E. et al. Bad, a heterodimeric partner for Bcl-x L and Bcl-2, displaces Bax and promotes cell death. Cell. 80, 285–291 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle J. K. & Letai A. Control of mitochondrial apoptosis by the Bcl-2 family. J. Cell Sci. 122, 437–441 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Nylander K. D., Yan C. & Schor N. F. Role of caspase 3-dependent Bcl-2 cleavage in potentiation of apoptosis by Bcl-2. Mol. Pharmacol. 61, 142–149 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taru H., Yoshikawa K. & Suzuki T. Suppression of the caspase cleavage of β -amyloid precursor protein by its cytoplasmic phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 567, 248–252 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Srinivasula S. M., Druilhe A., Fernandes-Alnemri T. & Alnemri E. S. Caspase-2 induces apoptosis by releasing proapoptotic proteins from mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 13430–13437 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunyuzlu P. L., White W. H., Davis G. L., Hollis G. F. & Toyn J. H. A yeast genetic assay for caspase cleavage of the Amyloid-β precursor protein. Mol. Biotechnol. 15, 29–37 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberici A. et al. Presenilin 1 protein directly interacts with Bcl-2. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30764–30769 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftig P., Hartmann D. & De, Strooper. B. The function of presenilin-1 in amyloid β -peptide generation and brain development. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 249, 271–279 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastorino L. et al. The prolyl isomerase Pin1 regulates amyloid precursor protein processing and amyloid-β production. Nature. 440, 528–534 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathan N., Aime-Sempe C., Kitada S., Haldar S. & Reed J. C. Microtubule-targeting drugs induce bcl-2 phosphorylation and association with Pin1. Neoplasia. 3, 70–79 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajkowski E. M. et al. β -Amyloid peptide-induced apoptosis regulated by a novel protein containing a G protein activation module. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18748–18756 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumovski L. & Cleary M. L. The p53-binding protein 53BP2 also interacts with Bc12 and impedes cell cycle progression at G2/M. Mol Cell Biol. 16, 3884–3892 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotinopoulou A. et al. Efthimiopoulos S. BRI2 interacts with amyloid precursor protein (APP) and regulates amyloid β (Aβ ) production. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30768–30772 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer A., Ayllón V., Dumoutier L., Renauld J. C. & Rebollo A. Proapoptotic activity of ITM2B (s), a BH3-only protein induced upon IL-2-deprivation which interacts with Bcl-2. Oncogene. 21, 3181–3189 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal R., Ahmad N. & Kidwai J. R. In vitro conversion of proinsulin to insulin by cathepsin B in isolated islets and its inhibition by cathepsin B antibodies. Acta Diabetol. 17, 255–266 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. et al. In vivo imaging of proteolytic activity in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 105, 2766–2771 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando R. A. et al. Megalin is an endocytic receptor for insulin. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol . 9, 1759–1766 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veinbergs I. et al. Role of apolipoprotein E receptors in regulating the differential in vivo neurotrophic effects of apolipoprotein E. Exp. Neurol. 170, 15–26 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulescu R. T., Bellitti M. R., Ruvo M., Cassani G. & Fassina G. Binding of the LXCXE insulin motif to a hexapeptide derived from retinoblastoma protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 206, 97–102 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulescu R. T., Doklea E. D., Kehe K. & Muckter H. Nuclear colocalization and complex formation of insulin with retinoblastoma protein in HepG2 human hepatoma cells. J. Endocrinol. 166, R1–R4 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajas L. et al. The retinoblastoma-histone deacetylase 3 complex inhibits PPARγ and adipocyte differentiation. Dev Cell. 3, 903–910 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams M., Reginato M. J., Shao D., Lazar M. A. & Chatterjee V. K. Transcriptional activation by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ is inhibited by phosphorylation at a consensus mitogen-activated protein kinase site. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 5128–5132 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z. Z., Bruening W., Giasson B. I., Lee V. M. & Godwin A. K. Mechanisms of signal transduction-g-Synuclein Promotes Cancer Cell Survival and Inhibits Stress-and Chemotherapy Drug-induced Apoptosis by Modulating MAPK Pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35050–35060 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P. et al. Binding of Aβ to α -and β -synucleins: identification of segments in α -synuclein/NAC precursor that bind Aβ and NAC. Biochem. J. 323, 539–546 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafaeloff R., Patel R., Yip C., Goldfine I. D. & Hawley D. M. Mutation of the high cysteine region of the human insulin receptor alpha-subunit increases insulin receptor binding affinity and transmembrane signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 15900–15904 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill T. J., Craparo A. & Gustafson T. A. Characterization of an interaction between insulin receptor substrate 1 and the insulin receptor by using the two-hybrid system. Mol Cell Biol. 14, 6433–6442 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawka-Verhelle D. et al. Insulin Receptor Substrate-2 Binds to the Insulin Receptor through Its Phosphotyrosine-binding Domain and through a Newly Identified Domain Comprising Amino Acids 591786. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 5980–5983 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H. et al. Insulin-like growth factor I receptor signaling and nuclear translocation of insulin receptor substrates 1 and 2. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 472–486 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J. A. et al. Interleukins 2, 4, 7, and 15 Stimulate Tyrosine Phosphorylation of Insulin Receptor Substrates 1 and 2 in T Cells potential role of jak kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 28527–28530 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Margalet V. & Martin-Romero C. Human leptin signaling in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: activation of the JAK-STAT pathway. Cell. Immunol. 211, 30–36 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui L., Yuan M., Frantz D., Shoelson S. & White M. F. SOCS-1 and SOCS-3 block insulin signaling by ubiquitin-mediated degradation of IRS1 and IRS2. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42394–42398 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørbæk C. et al. SOCS3 mediates feedback inhibition of the leptin receptor via Tyr985. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 40649–40657 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gual P., Baron V., Lequoy V. & Van Obberghen E. Interaction of Janus Kinases JAK-1 and JAK-2 with the Insulin Receptor and the Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Receptor 1. Endocrinology. 139, 884–893 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. et al. Evidence that the diabetes gene encodes the leptin receptor: Identification of a mutation in the leptin receptor gene in db/db mice. Cell. 84, 491–495 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers M. G. et al. The COOH-terminal tyrosine phosphorylation sites on IRS-1 bind SHP-2 and negatively regulates insulin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 26908–26914 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter L. R. et al. Enhancing leptin response by preventing SH2-containing phosphatase 2 interaction with Ob receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95, 6061–6066 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelzl U. et al. A human protein-protein interaction network: a resource for annotating the proteome. Cell. 122, 957–968 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers M. P. TYK2 and JAK2 are substrates of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47771–47774 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabolotny J. M. et al. PTP1B regulates leptin signal transduction in vivo. Dev Cell. 2, 489–495 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock M. T., Brooks W. H. & Roszman T. L. Calcium-dependent Signaling Pathways in T Cells Potential Role Of Calpain, Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1b, And P130cas In Integrin-Mediated Signaling Events. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 33377–33383 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro H. et al. Interaction of human calpains I and II with high molecular weight and low molecular weight kininogens and their heavy chain: mechanism of interaction and the role of divalent cations. Biochemistry. 26, 2863–2870 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A., Smalheiser N. R., Markaryan A. & Kaplan A. Evidence for binding of the ectodomain of amyloid precursor protein 695 and activated high molecular weight kininogen. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1571, 225–238 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]