Abstract

Proliferating-cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) is a DNA sliding clamp with an essential function in DNA replication and a key role in tolerance to DNA damage by ensuring the bypass of lesions. In eukaryotes, DNA damage tolerance is regulated by ubiquitylation of lysine 164 of PCNA through a well-known control mechanism; however, the regulation of PCNA deubiquitylation remains poorly understood. Our work is a systematic and functional study on PCNA deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs) in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Our study reveals that the deubiquitylation of PCNA in fission yeast cells is a complex process that requires several ubiquitin proteases dedicated to the deubiquitylation of a specific subnuclear fraction of mono- and di-ubiquitylated PCNA or a particular type of poly-ubiquitylated PCNA and that there is little redundancy among these enzymes. To understand how DUB activity regulates the oscillatory pattern of ubiquitylated PCNA in fission yeast, we assembled multiple DUB mutants and found that a quadruple mutation of ubp2+, ubp12+, ubp15+, and ubp16+ leads to the stable accumulation of mono-, di-, and poly-ubiquitylated forms of PCNA, increases S-phase duration, and sensitizes cells to DNA damage. Our data suggest that the dynamic ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation of PCNA occurs during S-phase to ensure processive DNA replication.

Living cells tolerate DNA damage during S-phase to prevent the risk of irreversible DNA replication fork collapse1. DNA damage tolerance is based on translesion synthesis (TLS), which involves a dual mechanism, primarily mediated by specialized low fidelity DNA polymerases called TLS-polymerases. These TLS polymerases can be mutagenic because they induce an error-prone process that causes mutations. The second mechanism depends on template switching, the error-free component of the bypass that involves sister-strand pairing between nascent chains within the same replication fork. It is well established that both mechanisms efficiently prevent replisome stalling at damaged sites. Eukaryotic cells regulate the choice of alternative pathways/mechanisms to bypass DNA lesions during S-phase through the ubiquitylation of proliferating-cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), a processivity factor for DNA synthesis2,3. The monoubiquitylation of PCNA (ubPCNA) at Lys164 enhances the affinity of error-prone TLS DNA polymerases, and further polyubiquitylation of Lys164-monoubiquitylated PCNA promotes template switching2,3,4,5,6. The evolutionarily conserved Lys164-ubiquitylation of PCNA and its crucial role in DNA damage tolerance are well understood7,8,9. However, little is known regarding the significance of PCNA deubiquitylation in eukaryotes.

Work from the past decade has identified mammalian Usp1, human Usp10, and budding yeast Ubp10 as major deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs) for PCNA1,10,11,12. Usp1 has been identified as a DUB that deubiquitylates mono-ubPCNA and mono-ubFANCD2 in human cells10. Upon UV light-induced DNA damage, Usp1 undergoes autocleavage, and PCNA therefore becomes ubiquitylated, suggesting that Usp1 continuously deubiquitylates PCNA in the absence of DNA damage. However, ubPCNA accumulation does not correlate with Usp1 (auto-induced) proteolysis when cells are exposed to other genotoxic agents, such as MMS and mitomycin C13,14, or the DNA replication blocking agent HU15, suggesting either that another human PCNA DUB exists or that Usp1 activity is regulated in a different manner in response to other DNA damaging agents. Therefore, the relevance of USP1 in reverting PCNA ubiquitylation when confronted with different DNA-damaging agents remains unclear. This is an important issue, particularly because PCNA ubiquitylation is required for mammalian cell survival not only after UV irradiation but also upon exposure to HU and MMS16,17. However, consistent with a role as a PCNA DUB, the depletion of chicken USP1 in DT40 cells or in murine Usp1−/− MEFs increases PCNA (and also FANCD2) mono-ubiquitylation14,18. More recently, it has been shown that upon UV-mediated DNA damage, HeLa cells rely on USP10 to deubiquitylate ISGylated-PCNA12. We have previously shown that the ubiquitin protease Ubp10 deubiquitylates K164 mono-and di-ubiquitylated PCNA during S phase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae11. Furthermore, we demonstrated that Ubp10 forms a complex with PCNA in vivo, as expected for an enzyme-substrate complex. Additionally, in agreement with a direct role as a PCNA DUB, we found that only catalytically active Ubp10 reverts PCNA ubiquitylation. However, despite the identification of Usp1, Usp10, and Ubp10 as PCNA DUBs, little is known regarding the deubiquitylation of ubPCNA in any other model organisms.

In the fission yeast S. pombe, a key model organism in understanding the cell division cycle, the proteases that deubiquitylate ubPCNA remain unknown. Potential candidates in fission yeast are 20 genes that encode different deubiquitylating enzymes or DUBs including 14 ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), 2 ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), 2 ovarian tumour proteases (OTUs) and 2 JAB1/MPN/Mov34 metalloenzymes (JAMMs)19. Here, we show that Ubp2, Ubp15, and Ubp16 ubiquitin proteases, likely with the help of Ubp12, revert PCNA ubiquitylation in the fission yeast S. pombe during S-phase. All the DUBs involved in PCNA deubiquitylation in this model system belong to the same subfamily of ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs/UBPs). We found that each of these ubiquitin proteases is dedicated to the deubiquitylation of a specific subnuclear fraction or a particular type of ubiquitylated PCNA. Our data suggest that the dynamic ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation of PCNA occurs during S-phase and ensures proper DNA replication progression in S. pombe. Consequently, we propose that excessive DNA replication bypass interferes with the normal progression of DNA replication forks during S-phase.

Results

Analysis of PCNA deubiquitylation in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe

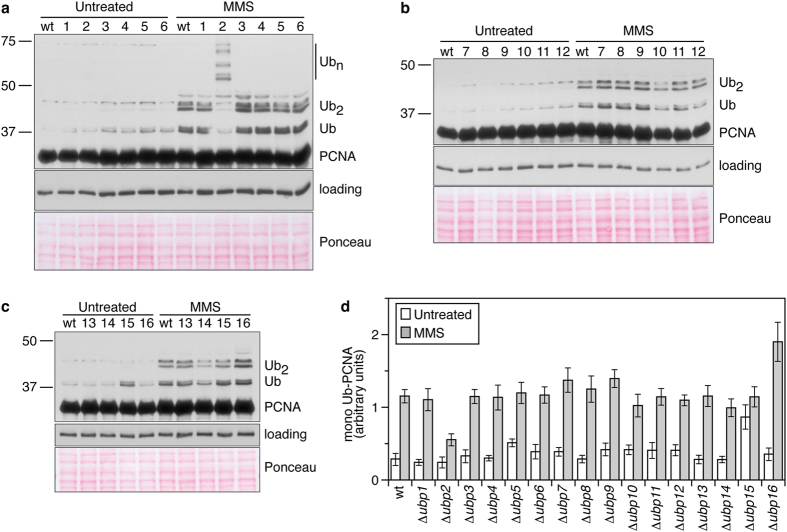

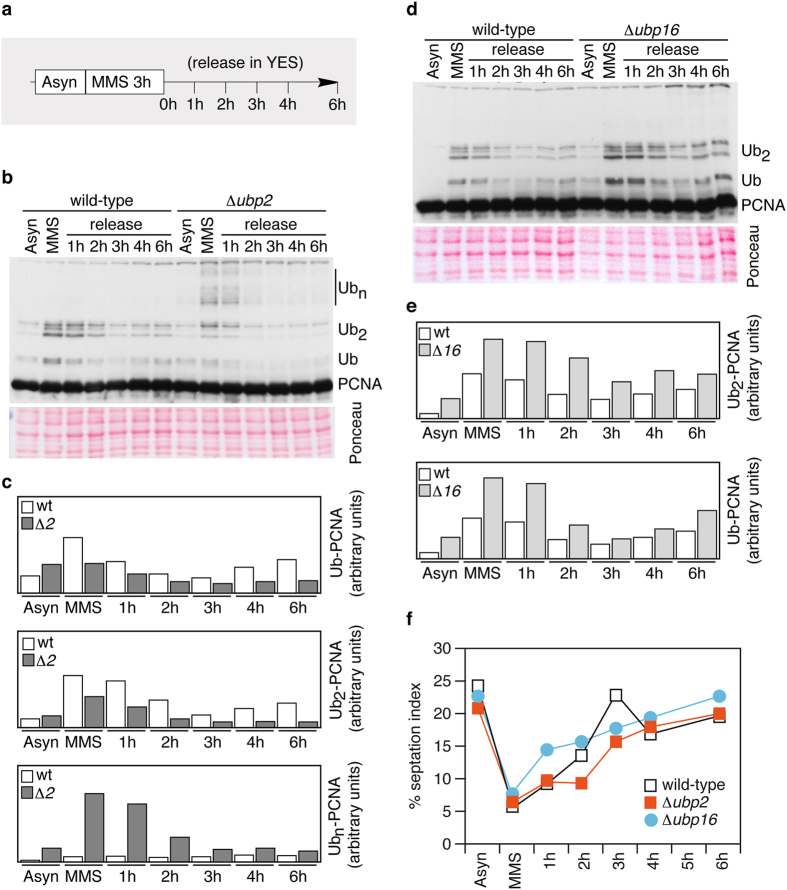

We reasoned that in fission yeast, the ubiquitylation of PCNA might be a reversible process catalysed by deubiquitylating enzymes (or DUBs), as is the case in budding yeast. We have previously shown that that the histone H2BK123 ubiquitin protease Ubp10 deubiquitylates ubPCNA in S. cerevisiae11. Budding yeast Ubp10 is a nucleolar ubiquitin protease of the USP family that is orthologous to Ubp16 in the distantly related fission yeast S. pombe19. Regarding PCNA modification, fission yeast is an interesting model organism because the sliding clamp is ubiquitylated during each S-phase even in the absence of exogenous DNA damage20. This is a strong difference from the budding yeast model in which ubPCNA is poorly detectable in undamaged cells11,21,22. The periodicity of PCNA ubiquitylation throughout the cell cycle (and our own observations) suggests the existence of an active deubiquitylating mechanism during S-phase20. Prompted by our interest in studying the potential conservation of the role of the USP family of ubiquitin proteases in PCNA deubiquitylation, we first analysed single mutants of every USP-subfamily DUB of S. pombe, looking for defects resulting in the accumulation of ubiquitylated forms of PCNA (Fig. 1). The fission yeast genome encodes 14 putative DUBs that belong to the USP subfamily (from ubp1+ to ubp16+). There are two other genes (ubp10+ and ubp13+) that encode proteins with DUB domains; however, they lack the full catalytic region required for protease activity19. To detect modified forms of the PCNA clamp, we used a previously characterized polyclonal antibody20 that specifically detects endogenous PCNA in S. pombe (TCA) cell extracts (Fig. S1). As shown in Fig. 1, Δ ubp2, Δ ubp15, and Δ ubp16 single mutants showed different defects. Δ ubp2 mutant cells accumulated PCNA forms with long ubiquitin chains (Fig. 1a, Fig. S2), Δ ubp15 mutants accumulated mono-ubiquitylated PCNA (plotted in Fig. 1d), particularly in asynchronous cultures (without exogenous DNA damage), and Δ ubp16 defective cells accumulated mono- and di-ubiquitylated PCNA (Fig. 1c). We then studied the ability of single Δ ubp2 and Δ ubp16 mutants to deubiquitylate ubPCNA upon release from HU or MMS treatments and found that, despite the fact that Δ ubp2 and Δ ubp16 single mutants accumulated more ubPCNA than wild-type controls, these single mutant cells efficiently deubiquitylated ubPCNA as observed in time-course assays (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. ubPCNA accumulation in fission yeast strains defective in specific USP-family ubiquitin proteases.

(a–c) Ubiquitylated PCNA accumulation in exponentially growing (untreated) or methyl methanesulfonate (MMS)-treated single ubp1 to ubp16 deletions in S. pombe. Wild-type and single mutant cells exponentially grown at 32 °C were treated for 3 hours with 0.01% MMS. Western blotting was used to analyse TCA-cell extracts for PCNA ubiquitylation, which was quantified and plotted. Cell extracts were resolved in 12% polyacrylamide gels and immunoblotted with affinity purified rabbit α -PCNA antibodies or α -tubulin (loading). Single ubp1 to ubp16 deletions in S. pombe are indicated by numbers. (d) Graph of mono-ubiquitylated PCNA accumulation in untreated and 0.01% MMS-treated single ubp1–16 deletions in S. pombe. Average values of the relative levels of mono-ubiquitylated PCNA from two independent assays are plotted. Error bars were calculated from two independent experiments and indicate the standard deviation.

Figure 2. Fission yeast cells lacking ubp2+ or ubp16+ deubiquitylate ubPCNA after MMS-induced DNA damage.

(a) Experimental design; exponentially growing cultures of wild-type, Δ ubp2, and Δ ubp16 strains were treated with 0.02% MMS and then released. Samples were taken at indicated intervals for cell cycle and Western analysis. (b) Western blot analysis in wild-type and Δ ubp2 mutant cells. ubPCNA signals were quantified and normalized to loading controls. (c) Quantification is shown in bar diagrams. (d) Western blot analysis in wild-type and Δ ubp16 mutant cells. As was previously performed, ubPCNA signals were quantified and normalized to loading controls. (e) Quantification is shown in bar diagrams. (f) Plots of septated (septation index) cells of the indicated strains in (b,d) are shown.

We next overexpressed every USP subfamily member controlled by the extensively used nmt1+ promoter of fission yeast and found that ubp12+ and ubp16+ efficiently reversed PCNA ubiquitylation, whereas ubp15+ overexpression partially impaired PCNA ubiquitylation (Fig. S3). Unexpectedly, ubp2+ overexpression did not affect the ubiquitylation of the sliding clamp. Strikingly, ubp12+ overexpression caused the deubiquitylation of ubPCNA, despite the fact that Δ ubp12 mutants have no observable defects in ubPCNA accumulation (Fig. 1C). We reasoned that this might be due to the redundant role of another USP subfamily (DUB family) member and initially concentrated our analysis on ubp12+, ubp15+, and ubp16+.

Analysis of the double mutants Δ ubp12 Δ ubp15 and Δ ubp12 Δ ubp16 and the triple mutant Δubp12 Δ ubp15 Δ ubp16 suggested a role for ubp12+ in ubPCNA deubiquitylation. Notably, the Δ ubp12 Δ ubp15 Δ ubp16 mutant accumulated high levels of ubPCNA and had an extended S-phase cell cycle (as elutriation assays revealed, Fig. S4). However, this Δ ubp12 Δ ubp15 Δ ubp16 triple mutant showed a poor growth phenotype that made it difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding the cell cycle analysis of PCNA deubiquitylation without further study (Fig. S4). Fully aware that ubp12+, ubp15+, and ubp16+ have additional roles in other cellular processes19 (and our own observations) and to minimize the mutation impact, we constructed a triple mutant in which both ubp12+ and ubp15+ were fused to a nuclear exclusion signal (NES) that efficiently prevented their accumulation in the nucleus and mimicked the defects in ubPCNA accumulation observed in single, double, or triple mutants (as shown for Ubp15 in Fig. S5). As expected, this ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 double-NES single deletion mutant grew better than the triple deletant and only showed a mild growth phenotype (further described later). Consistent with a role in the deubiquitylation of the sliding clamp, ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 cells accumulated high levels of ubPCNA (as shown later). Furthermore, the analysis of PCNA in this triple mutant in undamaged cells or cells blocked early in S-phase with hydroxyurea (HU) or cells treated with the alkylating agent methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) indicated that these three ubiquitin proteases were major players in reverting PCNA ubiquitylation during S-phase in fission yeast.

Multiple UBPs with specific roles, at specific sub-nuclear locations, are involved in ubPCNA deubiquitylation in the fission yeast S. pombe

The subcellular localization of S. pombe DUBs has been studied in depth19. Consistent with these data, we observed that Ubp16 localizes to the nucleolus (Fig. S5), whereas Ubp15 is present in the nucleus and in unidentified cytoplasmic spots/structures (Fig. S5) but does not co-localize with Ubp16 in the nucleolus (Fig. S5). GFP-tagged Ubp12 was also detected in the nucleus, and these data are consistent with the hypothesis that Ubp16 deubiquitylates PCNA in the nucleolus, whereas Ubp15 and Ubp12 primarily deubiquitylate non-nucleolar ubPCNA elsewhere in the nucleus. The combined analysis of nucleolar Ubp16 (Δ ubp16424–457-GFP) and nuclear Ubp12 and Ubp15 (ubp12-NES and ubp15-NES) mutants confirmed this hypothesis.

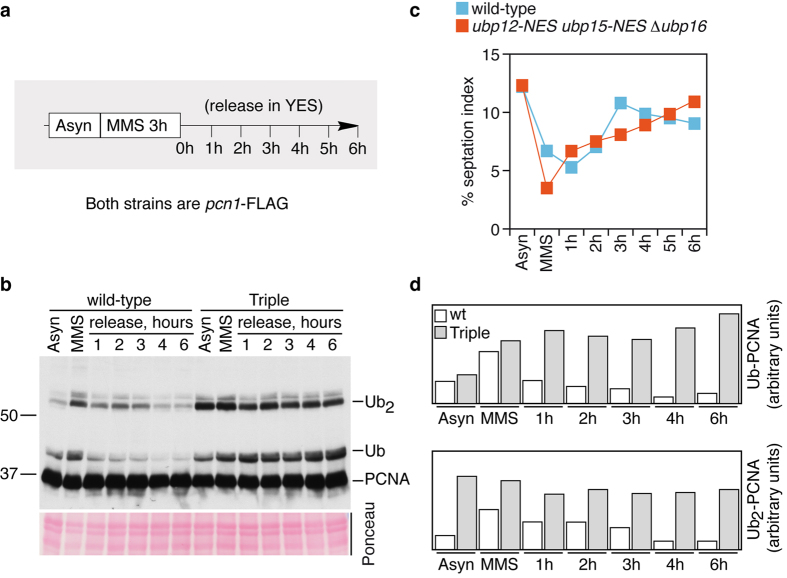

We next analysed the reversal of PCNA ubiquitylation in control and ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 strains upon release from MMS-mediated DNA damage, and deubiquitylation was blocked in the triple mutant (Fig. 3). This suggested that Ubp12, Ubp15, and Upb16 are all important to revert PCNA ubiquitylation throughout S-phase.

Figure 3. Ubp12, Ubp15, and Ubp16 are required for ubPCNA deubiquitylation after MMS-induced DNA damage.

(a) Experimental design; exponentially growing cultures of wild-type and ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 strains were treated for 3 hours with 0.01% MMS, washed twice in fresh pre-warmed media, and then released in YES media (in the absence of the alkylating chemical). Samples were taken at indicated intervals for cell cycle and Western analysis. Note that both strains were pcn1-FLAG tagged to detect PCNA. (b) Immunodetection of PCNA and modified PCNA forms with α -FLAG. (c) Percentage of septated cells (septation index) during the time-course experiment. (d) Mono- and di-ubiquitylated PCNA forms were quantified, normalized, and plotted.

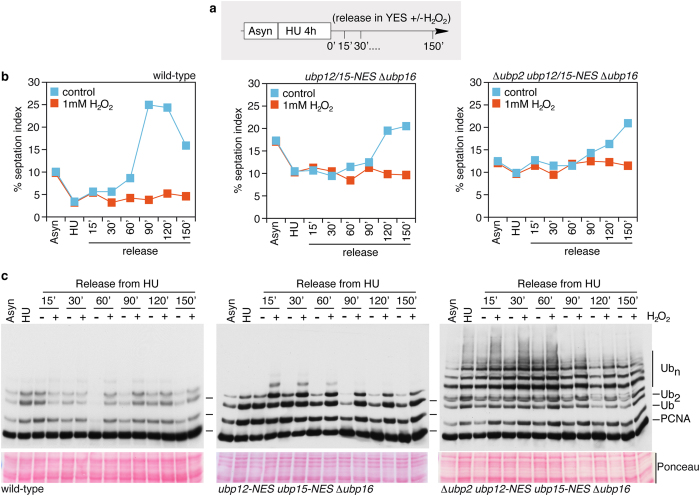

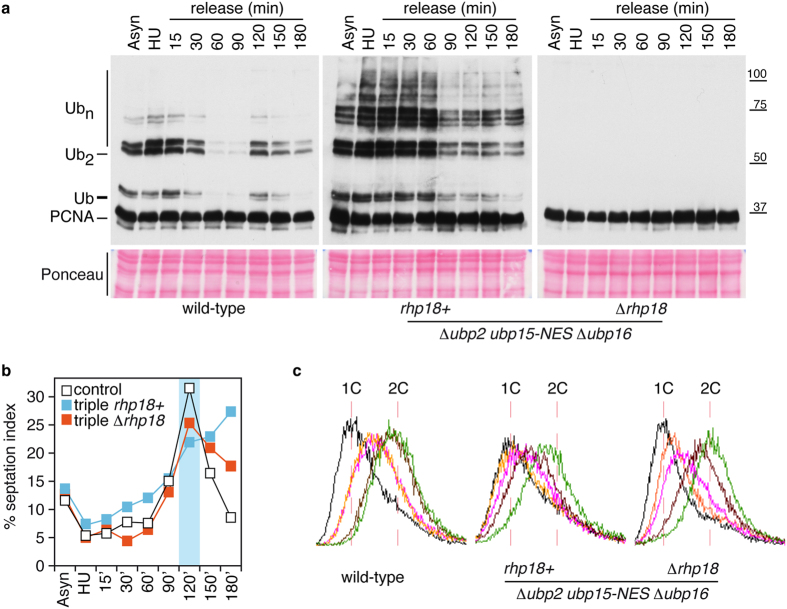

Despite high levels of accumulated ubiquitylated PCNA (Fig. S6), we also found that triple mutant ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 cells deubiquitylate ubPCNA upon release from HU (Fig. 4, middle graph and Western blot), indicating that at least one additional DUB is involved in the deubiquitylation of the sliding clamp. Significantly, we also noted that ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 triple mutant cells show a cell cycle delay; they progress slowly from the HU block in early S-phase to cytokinesis.

Figure 4. Analysis of PCNA ubiquitylation and cell cycle progression in S. pombe mutant cells defective in ubp2+, ubp12+, ubp15+, and ubp16+.

(a) Experimental design; exponentially growing cultures of wild-type, ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16, and Δ ubp2 ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 strains (as indicated) were synchronized early in S-phase by treating them for 4 hours with 20 mM HU, washed twice in fresh pre-warmed media, and then released in YES media in the absence (− ) or in the presence (+ ) of 1 mM H2O2. Samples were taken at indicated intervals for cell cycle and Western analysis. (b) Percentage of septated cells (septation index) during the time-course experiment in the indicated strains. (c) Immunodetection of PCNA and modified PCNA forms with α -FLAG. Note that the three strains were pcn1-FLAG tagged to detect PCNA.

The unique role of Ubp2 in ubPCNA deubiquitylation

We observed that wild-type cells accumulate PCNA with long ubiquitin chains when exposed to hydrogen peroxide (closely resembling ubp2 mutants). K63-linked polyubiquitylation has been associated with the inactivation of S. cerevisiae Ubp2 in response to oxidative stress23. Some DUBs can be reversibly inactivated through the oxidation of their catalytic cysteine by H2O224, and fission yeast ubp2 mutants accumulate K63-linked polyubiquitylated PCNA (Figs 1 and 2). Thus, we predicted that Ubp2 would revert PCNA ubiquitylation in a concerted manner with Ubp12, Ubp15, and Ubp16 to fully deubiquitylate the sliding clamp (particularly in response to endogenous and exogenous oxidative DNA damage). We reasoned that the periodic pattern of PCNA ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation would be lost in cells lacking all relevant fission yeast PCNA-DUBs. Therefore, we next combined Δ ubp2 with ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 and evaluated ubPCNA stability in time-course experiments with HU-presynchronized cells released in the absence or in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. Upon release from the HU arrest in early S-phase, ubiquitylated PCNA remained fairly stable over time in quadruple mutant cells, which was similar to cells fully defective in PCNA deubiquitylation and released in hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 4). We also found that Δ ubp2 ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 quadruple mutant cells have a strong cell cycle delay. Together, these converging lines of evidence suggest that Ubp2, Ubp12, Ubp15, and Ubp16 are major (K164) ubPCNA ubiquitin proteases in fission yeast.

As shown above, we also noticed the accumulation of PCNA with long ubiquitin chains in ∆ubp2 cells treated with MMS (Figs 1 and 2), but these chains were removed efficiently when the DNA damage was removed. To test whether the removal of these long chains on PCNA was dependent upon Ubp12/15/16, we studied Δ ubp2 ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 cells. Upon release from DNA damaging conditions, PCNA deubiquitylation was blocked in the quadruple mutant. Although Ubp2 is particularly important for the removal of long ubiquitin chains from PCNA in the presence of DNA damage, it appears that Ubp12/15/16 can cooperate to remove these chains from PCNA once the damage has been removed.

Next, we tested the importance of PCNA deubiquitylation in vivo; we reasoned that impeding a relevant S-phase event should have an impact on cell-cycle progression. We found that the combination of Δ ubp2, ubp12-NES, ubp15-NES, and Δ ubp16 leads to growth defects and increased sensitivity to replication stress induced by HU treatment or DNA damage (Fig. S7).

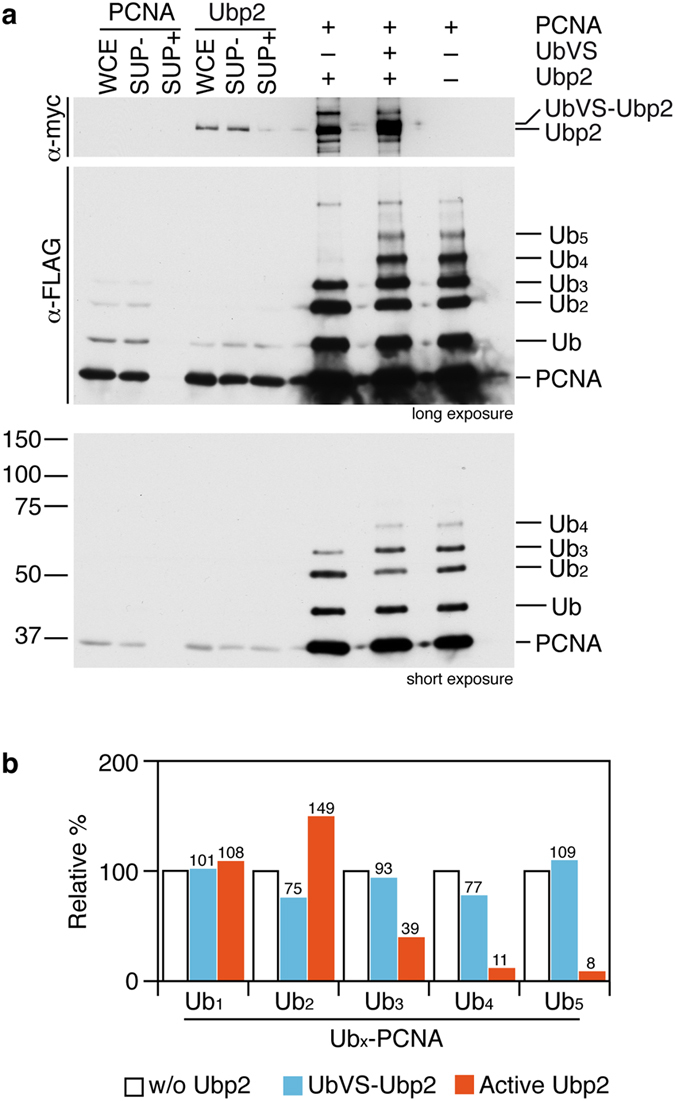

Ubp2 deconjugates K63-linked poly-ubiquitin chains from K164 poly-ubiquitylated PCNA in vitro

We next tested the ability of immunoprecipitated Ubp2-myc protein to deubiquitylate PCNA in an in vitro (ubiquitin protease) assay using mono- and poly-ubiquitylated PCNA-FLAG (ub-, ub2-, ub3-, ub4- and ub5-PCNA-FLAG) as a substrate immunoprecipitated from a Δ ubp2 ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 pcn1-FLAG strain (Fig. 5). Ubp2-myc efficiently deubiquitylated ub5-PCNA, ub4-PCNA, and, less efficiently, Ub3-PCNA, but it was unable to deubiquitylate ub- or ub2-PCNA. In fact, ub2-PCNA forms accumulated in the in vitro reactions, suggesting that polyubiquitylated PCNA with 3 or more ubiquitin moieties was converted into di-ubiquitylated PCNA by Ubp2. This in vitro ubiquitin protease activity of Ubp2 towards polyubiquitylated PCNA was directly inhibited by binding UbVS to the enzyme prior to the protease reaction, indicating that an active Ubp2-associated protease activity is required to remove these unusually long polyubiquitin chains from PCNA. These experiments support the hypothesis that Ubp2 deubiquitylates K63-linked ub3-to-ub5-polyubiquitylated PCNA forms.

Figure 5. Ubp2 removes long K63-linked ubiquitin chains from poly-ubiquitylated PCNA in vitro.

(a) Ubp2-myc deubiquitylates in vitro polyubiquitylated PCNA. Mono-, di-, and poly-ubiquitylated (ub3-to-ub6) PCNA was obtained by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody from a Δ ubp2 ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 pcn1-FLAG strain (synchronized in early S-phase; 3 hours 20 mM HU). Immunoprecipitated samples were divided in three; two of the aliquots were incubated with immunoprecipitated Ubp2-myc in the absence or in the presence of UbVS to inhibit the protease activity of Ubp2 (as described in the Methods section). The third aliquot served as a reference sample of the immunoprecipitated PCNA. PCNA deubiquitylation was detected by the distinctive SDS-PAGE gel mobility of the different PCNA forms. Whole cell extracts (WCE), depleted supernatants (SUP+ ), and non-depleted supernatants (SUP− ) from PCNA-FLAG and Ubp2-myc strains are also shown. (b) Signals of the different PCNA forms in the deubiquitylation reactions and controls resolved in the Western blots were quantified and plotted.

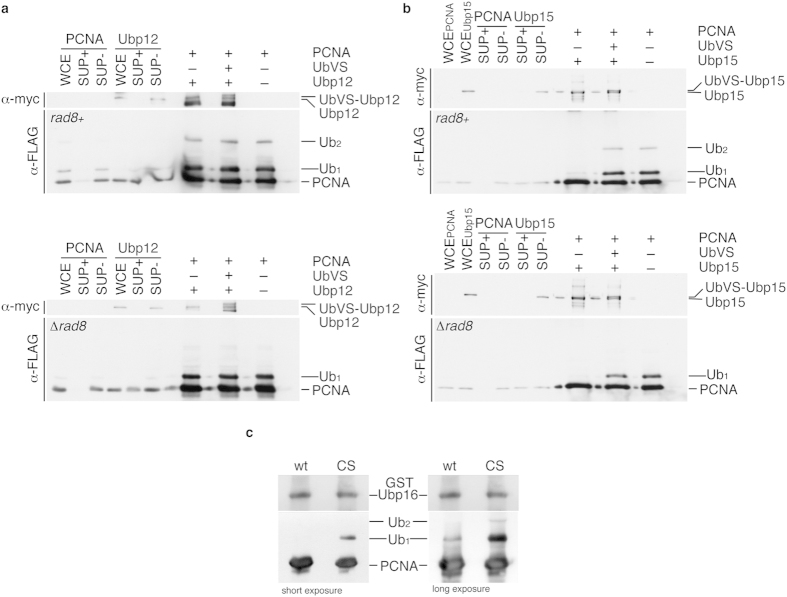

Ubp15 and Ubp16 deconjugate ubiquitin and K63-linked di-ubiquitin chains from K164 mono- and di-ubiquitylated PCNA in vitro

Having shown in vitro that Ubp2 removes ubiquitin and ubiquitin chains from polyubiquitylated PCNA (with 3 or more ubiquitin moieties), thus indicating that Ubp2 is an (ub3-to-ub8PCNA) endo-deubiquitylase, we reasoned that perhaps the Ubp2 function in vivo is to shorten polyubiquitylated PCNA (›ub3PCNA) to allow Ubp12, Ubp15, and Ubp16 to fully deubiquitylate the sliding clamp. If this hypothesis is correct, we should be able to assemble an in vitro reaction and show that Ubp12, Ubp15, and Ubp16 remove ubiquitin from mono- and di-ubiquitylated PCNA. Therefore, we tested the activity of Ubp12, Ubp15, and Ubp16 in ubiquitin protease assays using mono- and di-ubiquitylated PCNA as substrates immunoprecipitated from ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 pcn1-FLAG (as a source of ub1- and ub2-PCNA) and ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 Δ rad8 pcn1-FLAG (as a source of ub1-PCNA) strains (Fig. 6). In our in vitro enzymatic assays, Ubp12 failed to deubiquitylate ub1- or ub2-PCNA. However, we found that Ubp15-myc, Ubp16-myc, and GST-Ubp16 efficiently deubiquitylated both mono- and di-ubiquitylated PCNA forms (Fig. 6B,C, Fig. S8). These experiments, together with in vivo evidence, support the conclusion that Ubp15 and Ubp16 are substrate/PCNA-specific DUBs that deubiquitylate K164 mono-ubiquitylated PCNA and (K63-linked) K164 di-ubiquitylated PCNA.

Figure 6. Ubp15 and Ubp16 deubiquitylate mono- and di-ubiquitylated PCNA in vitro.

Mono- and di-ubiquitylated PCNA was obtained by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody from a ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 pcn1-FLAG strain (rad8+ blot) and mono-ubiquitylated PCNA was obtained from a ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 Δ rad8 pcn1-FLAG strain (Δ rad8 blot) (both strains were synchronized in early S-phase; 3 hours 20 mM HU). In each case (rad8+ and Δ rad8), immunoprecipitated samples were divided in three, and two of the aliquots were incubated with immunoprecipitated Ubp12-myc or Ubp15-myc (as indicated) in the absence or in the presence of UbVS to inhibit any UBP activity (as described in the Methods section). The third aliquot served as a reference sample of the immunoprecipitated PCNA. PCNA deubiquitylation was detected by the distinctive SDS-PAGE gel mobility of the different PCNA forms. Whole cell extracts (WCE), depleted supernatants (SUP+ ), and non-depleted supernatants (SUP− ) from PCNA-FLAG and Ubp12-myc or Ubp15-myc strains are also shown. (a) Active Ubp12 fails to deubiquitylate PCNA in vitro. (b) Immunoprecipitated Ubp15-myc deubiquitylates both mono- (ub1) and di-ubiquitylated (ub2) PCNA in vitro. (c) GST-Ubp16 deubiquitylates ub1-PCNA and ub2-PCNA in vitro. Purified GST-Ubp16 and GST-Ubp16CS proteins from E. coli were assayed in vitro for their ability to deubiquitylate PCNA. Note that GST-Ubp16 but not the catalytically inactive form GST-Ubp16CS (C134S) deconjugated ubiquitin from mono- and di-ubiquitylated PCNA.

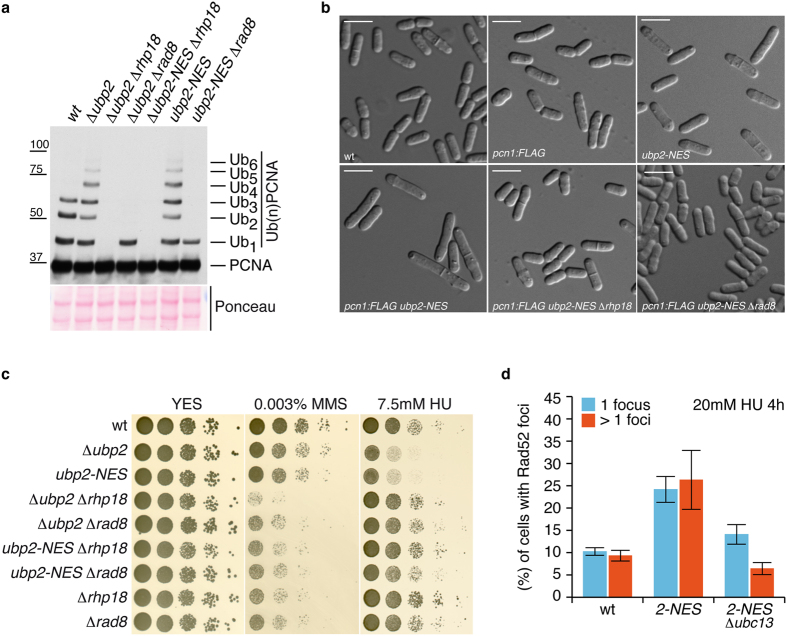

Mutation of Rhp18Rad18 or Rad8Rad5 PCNA-ubiquitin protein ligases suppresses PCNA-DUBs-associated cell cycle phenotypes

As previously shown, ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 triple mutant cells show a solid cell cycle delay phenotype when combined with Δ ubp2 (graphs in Fig. 4). This additive effect suggested that ubp2 mutants have a mild cell cycle phenotype that is easier to detect in combination with mutations of other ubiquitin proteases controlling PCNA deubiquitylation. In the course of our studies, we found that ubp2 mutant cells in combination with pcn1-FLAG were elongated compared to the wild-type or pcn1-FLAG controls (Fig. 7). It is important to mention that neither pcn1-FLAG cells nor ubp2 mutants have a strong phenotype on their own (Fig. 7). We reasoned that if there is a link between this elongated cell phenotype and the accumulation of ubiquitylated PCNA, preventing PCNA ubiquitylation would rescue this cell cycle defect. Therefore, we examined the pcn1-FLAG ubp2-NES/Δ ubp2-associated cell cycle phenotype in Δ rhp18 or Δ rad8 mutant strains defective in the E3 ubiquitin protein ligases that control PCNA mono- and poly-ubiquitylation, respectively20. Significantly, the cdc-like phenotype of ubp2-NES and Δ ubp2 was efficiently suppressed by preventing K164 PCNA ubiquitylation (in a Δ rhp18 mutant) or polyubiquitylation (in a Δ rad8 mutant) because the cell size of exponentially growing cells from ubp2-NES Δ rhp18, Δ ubp2 Δ rhp18, ubp2-NES Δ rad8, or Δ ubp2 Δ rad8 mutants was indistinguishable from the cell size of wild-type controls. These results suggest that Ubp2 has a direct role in PCNA deubiquitylation that is relevant for normal cell cycle progression in fission yeast. We also tested whether the deletion of rhp18+ would suppress the slow S-phase phenotype of the Δ ubp2 ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 quadruple mutant (Fig. 4), but this quintuple mutant grew poorly and prevented analysis requiring presynchronization. However, further support for the cell cycle role of PCNA deubiquitylation comes from evidence regarding the rescue of the S-phase and septation delays of a Δ ubp2 ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 triple mutant by deleting the PCNA ubiquitin ligase Rhp18 (Fig. 8). All the evidence suggests that PCNA deubiquitylation is an important cell cycle event in S. pombe.

Figure 7. ubp2-NES-associated cell elongation phenotype is suppressed by preventing K164 PCNA ubiquitylation.

(a) Immunodetection of ubiquitylated forms of PCNA-FLAG in pcn1-FLAG (wt), pcn1-FLAG Δ ubp2, pcn1-FLAG Δubp2 Δ rhp18, pcn1-FLAG Δ ubp2 Δrad8, pcn1-FLAG ubp2-NES, pcn1-FLAG ubp2-NES Δ rhp18, and pcn1-FLAG ubp2-NES Δ rad8 cell extracts to show that the accumulation of (long K63-linked ubiquitin chained) polyubiquitylated PCNA forms in ubp2 mutant cells depends on the K164 monoubiquitylation of PCNA (Rhp18) and the K63-linked di-ubiquitylation of mono-ubiquitylated PCNA (Rad8). (b) Optical Nomarski images of wild-type, pcn1-FLAG, pcn1-FLAG ubp2-NES, pcn1-FLAG ubp2-NES Δrhp18, and pcn1-FLAG ubp2-NES Δ rad8 cells (as indicated). Note that the elongated cell phenotype in pcn1-FLAG ubp2-NES cells is suppressed by Δrhp18 or Δrad8 deletion. (c) Epistasis analysis of Δ rhp18, Δrad8, and ubp2 mutant alleles. Ten-fold dilutions of the indicated strains incubated at 32 °C on YES plates with or without MMS or HU (as indicated). Note that Δubp2 Δ rhp18, Δ ubp2 Δ rad8, ubp2-NES Δ rhp18, and ubp2-NES Δ rad8 double mutants behave like single Δ rhp18 or Δ rad8 mutants, indicating that Δ rhp18 and Δ rad8 are epistatic to Δ ubp2 and ubp2-NES. (d) The ubp2-NES allele accumulates Rad52-foci in a Ubc13-dependent manner. (wt) wild-type, (2-NES), ubp2-NES and (2-NES Δ ubc13), ubp2-NES Δ ubc13. Bar graph of nuclei containing single or multiple Rad52-foci in fission yeast strains after 4 hours of 20 mM HU treatment. The results are representative of three independent experiments to obtain an estimate of error (where n is greater than 1,200 for each sample).

Figure 8. Rescue of cell cycle phenotypes in Δubp2 ubp15-NES Δubp16 triple mutants through the suppression of K164-linked PCNA ubiquitylation.

Experimental design; exponentially growing cultures of wild-type, Δ ubp2 ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 (triple), and Δ ubp2 ubp15-NES Δubp16 Δ rhp18 strains (as indicated) were synchronized early in S-phase by treating them for 4 hours with 20 mM HU, washed twice in fresh pre-warmed YES media, and then released. Samples were taken at indicated intervals for cell cycle position and Western analysis. (a) Immunodetection of ubiquitylated forms of PCNA-FLAG in pcn1-FLAG (wt), pcn1-FLAG Δ ubp2 ubp15-NES Δ ubp16, and pcn1-FLAG Δ ubp2 ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 Δ rhp18 cell extracts to show that the accumulation of (long K63-linked ubiquitin chains) polyubiquitylated PCNA forms in these triple mutant cells depends on the K164 monoubiquitylation of PCNA (Rhp18). (b) Percentage of septated cells (septation index) during the time-course experiment in the indicated strains. (c) DNA content analysis by FACS of cell samples synchronized in HU (black lines) and 15 (orange lines), 30 (pink lines), 60 (brown lines), and 90 (green lines) minutes after the release in YES. Note that the S-phase and septation delays of Δ ubp2 ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 triple mutants were reverted in a Δ rhp18 background.

S-phase Rad52-dependent template switching analysis in fission yeast strains with specific defects in ubPCNA deubiquitylation

In this work, we have related the deubiquitylation of PCNA to the enzymatic activity of the USP-family DUBs Ubp2, Ubp12, Ubp15, and Ubp16 in the nucleus. Notably, we observed that ubp2, ubp15, and ubp16 single mutants show specific defects regarding ubPCNA accumulation in vivo (Figs 1 and 2, Fig. S2). On the basis of these results, we were interested in understanding whether these unique defects are associated with specific physiologically relevant phenotypes, particularly those linked to tolerance to DNA damage during S-phase. In budding and fission yeast, Rad52 has been associated with the template switching branch of the tolerance to DNA damage pathway25,26,27,28; for this reason, we studied the accumulation of Rad52 in nuclear foci in ubp2, ubp12, ubp15, and ubp16 mutant cells blocked/synchronized in early S-phase with HU. We determined the number and percentage of cells accumulating single or multiple nuclear Rad52 foci after a 4-hour block in HU (Fig. 7D, Fig. S9). Consistent with a lower number of template switching events, we observed a decrease in the percentage of cells with nuclear Rad52 foci in ubp15 and ubp16 mutant cells in early S-phase compared to controls (Fig. S9). Interestingly, we found that ubp2 mutant cells accumulate single and multiple Rad52 foci. We also found that this phenotype depended entirely on PCNA polyubiquitylation because it was efficiently suppressed by the deletion of ubc13+. Ubc13 is a PCNA E2 K63-polyubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that forms part of the Rad8/Mms2-Ubc13 complex that controls translesion synthesis in S. pombe29. This evidence suggests that in fission yeast the accumulation of long polyubiquitylated PCNA forms enhances Rad52-dependent template switching in early S-phase.

Discussion

In this study, we explain how ubPCNA is deubiquitylated in S. pombe due to the concerted nuclear activity of four different members of the USP family of ubiquitin proteases: Ubp2, Ubp12, Ubp15, and Ubp16. Defects in Ubp15 primarily result in the accumulation of mono-ubPCNA, particularly during the S-phase of a normal cell cycle. However, this ∆ubp15 does not affect PCNA ubiquitylation upon the treatment of cells with DNA damaging agents. In contrast, Ubp16 appears to deubiquitylate mono- and di-ubPCNA in the nucleolus in response to DNA damage, whereas Ubp12 has the same activity in the non-nucleolar fraction of the nucleus. Ubp12 might act redundantly with Ubp15 because the mutation of ubp12+ lacks a phenotype but greatly enhances the phenotype of ubp15 single and ubp15 ubp16 double mutants. The fourth DUB to regulate PCNA, Ubp2, removes long K63-linked ubiquitin chains that accumulate in wild-type cells in response to DNA damage. All four ubiquitin proteases are active throughout the cell cycle and likely deubiquitylate the sliding clamp in response to the presence of ubPCNA during S-phase. Significantly, their concerted role in reverting PCNA ubiquitylation is important for cell cycle progression and, particularly, for cells to respond to DNA damage or replication blocks. A multiple/quadruple mutant (Δ ubp2 ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16), which is fully defective in ubPCNA deubiquitylation, is viable, but the cells appeared elongated. This cdc-like phenotype depended at least in part on the ubp2 mutation because it was reverted/suppressed by preventing PCNA ubiquitylation and/or polyubiquitylation, indicating that the cell cycle phenotype is the consequence of the excess PCNA ubiquitylation. Further support for this hypothesis comes from the observation that links PCNA ubiquitylation with the S-phase delay detected in Δ ubp2 ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 triple mutants.

Our observations are consistent with the idea that the impairment of ubPCNA deubiquitylation leads to an extended S-phase in S. pombe, and they suggest that the timely removal of PCNA ubiquitylation after lesion bypass is necessary to ensure processive DNA replication. In eukaryotes, lesion bypass at replication forks relies on polymerase switching, a replicative-to-TLS DNA polymerase exchange based on PCNA ubiquitylation16,30,31,32,33. Recent studies suggest that PCNA deubiquitylation is required after lesion bypass synthesis to resume normal DNA synthesis by Polδ 12,34. In particular, it has been shown that PCNA monoubiquitylation prevents Polδ from replacing Polη in a budding yeast in vitro reconstituted system34. In human cell lines, the replacement of Polη by replicative DNA polymerases (in TLS termination) is more complex; three alternative mechanisms have been described, including DVC1/SPARTAN accumulation at stalled forks35, PAF15 binding to PCNA36, and USP10-dependent ISGylated-PCNA deubiquitylation12. However, a key unanswered question is whether PCNA deubiquitylation is an S-phase-specific modification, thus allowing a rapid resumption of processive DNA replication after lesion bypass. Here, we provide the first in vivo evidence that links the deubiquitylation of the sliding clamp with cell cycle progression control during S-phase.

Tolerance to DNA damage is based on a non-processive DNA replication event called translesion synthesis, which is either a low-fidelity mechanism (associated with TLS-DNA polymerases) or a complex molecular tool (involving template switching) that can be used to bypass DNA lesions at the replication fork during S-phase37,38,39,40. If we hypothesized that ubPCNA deubiquitylation is important to prevent the expanded use of translesion synthesis, we can predict that defects in this deubiquitylating process would eventually lead to an extended S-phase due to the nature of this DNA replication event that will likely slow down DNA synthesis at the replication fork. Furthermore, even if translesion synthesis works primarily during late DNA replication (i.e., S/G2 boundary) defects in ubPCNA deubiquitylation can cause a delay in the completion of S-phase. Therefore, in eukaryotes, translesion synthesis may result in slow DNA replication, as has been shown for DNA polymerase switching in E. coli41. Our results show that there is a strong correlation between the accumulation of ubiquitylated PCNA and extended S-phase duration.

Our observations force us to ask why the deubiquitylation of ubPCNA in the fission yeast is this complex. It is noteworthy to mention that all PCNA ubiquitin proteases described in this work have other substrates distinct from PCNA19. Indeed, we show here that the reversion of PCNA ubiquitylation involves three or likely four different ubiquitin proteases in S. pombe. This observation suggests that fission yeast evolved a redundant system to ensure backup activity to maintain the controlled ubiquitylation of the sliding clamp. However, this possibility contradicts the idea that any backup system by gene redundancy is evolutionarily unstable42. In fact, we found that each of these ubiquitin proteases is dedicated to the deubiquitylation of a specific subnuclear fraction or a particular type of ubiquitylated PCNA, which in turn would suggest some degree of functional specialization (for further discussion see model in Fig. S10). Taken together, this evidence suggests that ubPCNA deubiquitylation in S. pombe is a case of distributed robustness, or perhaps more precisely, a case of division of labour.

The observed accumulation of mono-ubiquitylated PCNA in ubp15+ mutants, the increase shown in mono- and di-ubiquitylated PCNA in the Δ ubp16 strain, the synergistic effect of combining mutations in ubp15+ and ubp16+, and the evidence regarding the overexpression of both genes together with the in vitro data provide robust evidence that Ubp15 and Ubp16 revert the K164 mono- and di-ubiquitylation of PCNA. By reverting the ubiquitylation of PCNA, Ubp15 and Ubp16 activities counterbalance the ubiquitin ligase activity of the Rhp6/Rhp18 complex responsible for PCNA mono-ubiquitylation. Therefore, these two ubiquitin-specific proteases have the potential to be part of a safeguard mechanism limiting the residence time of TLS DNA polymerases in the replicating chromatin. In this context, an important observation presented in this work is that Ubp15 and Ubp16 can remove both mono- and di-ubiquitin from PCNA in vivo and in vitro, likely acting as substrate-specific DUBs. We have reported similar in vivo findings in budding yeast with Ubp10, a DUB related to fission yeast Ubp1611. Therefore, our results clearly suggest that these ubiquitin-specific proteases are crucial to downregulate simultaneously both error-prone and error-free branches of the tolerance pathway in fission yeast. The activity of Ubp15 and Ubp16Ubp10 would ensure a switch back to normal processive DNA replication without favouring a particular branch of the tolerance pathway. Finally, Ubp2 activity accumulates di-ubiquitylated PCNA. Therefore, together these three fission yeast ubiquitin proteases prevent an increment in mono-ubiquitylated PCNA that could eventually boost the unwanted interaction between TLS-polymerases and PCNA (error-prone and, thus, potentially mutagenic).

In the budding yeast, recent evidence demonstrated that DNA damage bypass-dependent PCNA ubiquitylation can be uncoupled from genome replication and is functional outside the limits of S-phase43,44, where it usually takes place43,45. It is already known that in fission yeast, as in budding yeast, PCNA ubiquitylation normally occurs during S-phase20,43. Here, our experiments confirm that S. pombe cells ubiquitylate and deubiquitylate PCNA during S-phase in a dynamic manner to ensure normal DNA replication, such that the ubiquitylation of PCNA is rapidly followed by the deubiquitylation of the sliding clamp from the beginning to the end of the S phase, likely to limit the window of opportunity for effective translesion synthesis to persist.

Methods

Yeast strains and cell culture

All strains used in this study were derived from wild-type 972h−. All strains were leu1-32 ura4-d18 except as noted. Standard molecular biology and genetic methods were used for the manipulation and construction of new strains46,47. Cultures were grown in appropriately supplemented yeast extract (YES media: yeast extract plus supplements [225 mg/l adenine, histidine, leucine, uracil, and lysine hydrochloride]). S. pombe cells were incubated at 30 °C unless otherwise specified. Strains containing repressible nmt1-regulated genes or nmt1-plasmids were grown in minimal medium (EMM) appropriately supplemented with 225 mg/l adenine and uracil and containing thiamine. Induction was performed by washing exponentially growing cultures twice and resuspending in medium without thiamine as previously reported48,49. Drug treatments were performed in exponentially cultures grown in YES or EMM that were appropriately supplemented as required (nmt1-induction experiments).

Imaging of Cells

The in vivo fluorescence imaging of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-, yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-, and red fluorescent protein (RFP)-tagged strains and 4′ ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining was performed in a Leica DM 6000B microscope (63X objective; 1,32 Oil Plan-APO) equipped with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER c4742-95 digital camera and MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). Fluorescence images were also collected using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope with a 63X or a 100X objective and a digital camera (Hamamatsu ORCA-ER c4742-95) and processed with Openlab 4.0.3 software (Improvision, Coventry, United Kingdom). To quantify Rad52-YFP foci, the appearance at least 1,200 nuclei from three separate experiments was examined for each strain and each time point.

in vivo nuclear staining was performed with 4′ ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) or Hoechst (bisbenzimide H 33342; Sigma, Madrid, Spain) as previously described49,50. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm and incubated in DAPI or Hoechst 1× for 15 min. To quantify the percentage of binucleated cells in certain experiments, cells were fixed in 70% ethanol, and then they were washed and resuspended in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (8.5 mM Na2HPO4·12H2O, 1.88 mM NaH2PO4·H2O, 130 mM NaCl) containing 1× DAPI as previously described51. At least 350 cells were classified as uni- or binucleated in each count. The septation index in wild-type cells and ubp2, ubp12, ubp15, and ubp16 mutant cells was determined by counting septated cells in vivo.

Tagging yeast proteins and gene deletion

Gene deletions or modifications were performed by PCR-mediated one-step gene replacement52. The selection markers used were KanMX6, HphMX4, or NatMX4, which allow selection with geneticin, hygromycin, and nourseothricin, respectively. We also used the ura4+ marker. The correct integration in the genome was confirmed by PCR with flanking and internal oligonucleotides and sequencing. In the case of tagged alleles, the expression of tagged proteins was confirmed by Western blotting. For tagging ubp2+, ubp12+, ubp15+, ubp16+, and pcn1+ with myc or FLAG, the myc and FLAG sequences were directly introduced at the 3′ end of the ORF of each gene. As indicated, in some experiments we used a tagged pcn1+ allele (endogenous promoter) to generate a Pcn1-FLAG fusion protein (with the FLAG epitope at the C-terminus). The FLAG-tagged strain behaved similarly to wild-type controls. For tagging with GFP, a flexible glycine-serine linker was introduced between the target protein and the tag.

The nuclear export signal (NES) of the heat-stable inhibitor of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (C-PKI; sequence: LALKLAGLDI)53 and a derivative of this NES with a tandem duplication of the export signal and the strong nuclear localization signal (NLS) of SV40 antigen (sequence: PKKKRKVG) were used to generate ubp2-GFP-NES, ubp12-GFP-NES, ubp15-mRFP-NES, and ubp15-mRFP-NLS forced localization mutants. Both the NLS (AAAPKKKRKVG) and the NES sequence (AAALALKLAGLNI) have been previously described54,55,56. For the generation of the forced localization mutants, the GFP-NES, mRFP-NES, and mRFP-NLS sequences were directly introduced at the 3′ end of the ORF of each ubp gene by PCR-mediated one-step gene replacement52. Plasmid vectors encoding GFP- or mRFP-NES and GFP- or mRFP-NLS forced localization cassettes will be described elsewhere.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

Protein extract preparation for Western analysis

TCA cell extracts were prepared and analysed as previously described for S. cerevisiae11,57,58. SDS-PAGE gels at 15%, 12%, 10%, and 8% were used for the detection of tubulin (15%); PCNA, PCNA-FLAG (12% and 10%), and Ubp16-myc (10%); and Ubp2-FLAG, Ubp2-myc, Ubp12-myc, and Ubp15-myc (8%). Whole-cell extracts for Western blotting were also obtained in HB buffer as previously described48.

Western blotting

Protein extracts and immunoprecipitates were electrophoresed using SDS-polyacrylamide gels ranging from 8 to 15%. For Western blots, 40–80 μ g of total protein extracts from each sample were blotted onto nitrocellulose, and proteins were detected using a characterized anti-PCNA affinity-purified polyclonal antibody (1:1500; a generous gift from Dr. Alan Lehmann). Tubulin was used as a loading control and detected with mouse TAT1 antitubulin monoclonal antibody (1:500). Antisera allowing the detection of PCNA and tubulin have been previously described20,59. We also used the anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (1:3000) and the anti-Myc monoclonal antibody (1:3000). For all antibodies mentioned, goat anti-rabbit (1:3500) or goat anti-mouse (1:2000) antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, United Kingdom) were used as secondary antibodies. Immunoblots were developed using Western Blotting Luminol Reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or SuperSignal (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) as required.

Protein extract preparation for immunoprecipitations

Soluble protein extracts were prepared basically as previously described11,49. Cells were collected, washed, and lysed in HB2T-lysis buffer using glass beads. The lysis buffer contained 60 mM β -glycerophosphate, 15 mM p-nitrophenylphosphate, 25 mM 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (pH 7.2), 15 mM MgCl2, 15 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 20 mg/ml leupeptin and aprotinin. The glass beads were washed with 500 μ l of HB2T, and the supernatant was recovered. For the immunoprecipitation studies or for the in vitro deubiquitylation assays, cell lysates (2–4 mg of protein) were incubated with the corresponding antibodies (2 μ g/mg extract) and protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen) for 3 h at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitates were collected by centrifugation, washed 2–5 times with lysis buffer, and subjected either to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis or in vitro analysis. Protein concentrations were measured using the BCA assay kit (Pierce).

In vitro deubiquitylation assays

PCNA-FLAG was efficiently immunoprecipitated from ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16, Δ ubp2 ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16, or ubp12-NES ubp15-NES Δ ubp16 Δ rad8 (pcn1-FLAG) strains (as indicated) after 2 hours in 20 mM HU. Ubp2-myc13, Ubp12-myc13, Ubp15-myc13, and Ubp16-myc13 were immunoprecipitated from asynchronous cultures of (ubp2 or ubp12 or ubp15 or ubp16) myc13-tagged strains (we found that Ubp2, Ubp12, Ubp15, and Ubp16 are active throughout the cell cycle). The immunoprecipitations were washed two times with lysis buffer and then twice with DUB buffer (60 mM HEPES at pH 7.6, 5 mM MgCl2, 4% glycerol). Beads were incubated overnight at 30 °C. As a negative control, we used inactive Usp2, Usp12, Usp15, and Usp16 bound to ubiquitin vinyl sulfone (UbVS) DUB activity probe. This probe covalently captures active DUB enzymes and therefore acts as a potent and irreversible inhibitor of DUBs through the covalent modification of the active site, as previously described60. The UbVS probe was used as suggested by the manufacturer (Enzo Life Sciences). In some cases, a standard GST-tagged Ubp16 and Ubp16CS protein expression and purification protocol was followed.

MMS and drug sensitivity assays

Exponentially growing cells were counted and serially diluted in YES media. Tenfold dilutions of equal numbers of cells were used. Seven microliters of each dilution was spotted onto YES plates or YES plates containing different concentrations of MMS, HU, or 4-NQO (as indicated), incubated at 30 °C, and scanned. Plates were incubated for 2 to 4 days at 30 °C and scanned. MMS and 4-NQO plates were always freshly prepared.

UV Sensitivity Assays

Cells were grown to logarithmic phase in YES media at 30 °C. Cultured cells were washed in fresh media, sonicated to disperse clumpy cells, and resuspended to a density of 2 × 106 cells per ml. Tenfold dilutions of these cells were spotted (7 μ l) onto YES plates. The plates were UV irradiated (as indicated) and incubated in the dark for 3 to 4 days at 30 °C and scanned.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Álvarez, V. et al. Orderly progression through S-phase requires dynamic ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation of PCNA. Sci. Rep. 6, 25513; doi: 10.1038/srep25513 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the B05 group at the Centro de Investigación del Cáncer for helpful discussions, we specially thank the help from Sara Ovejero. We also thank Rodrigo Bermejo (Centro Investigaciones Biologicas, CSIC) for helpful suggestions. We are very grateful to Alan R. Lehmann (University of Sussex) for the anti-PCNA antibody, we are also grateful to Peter M.M. Pryciak (University of Massachusetts Medical School), C. Vázquez de Aldana (IBFG, CSIC/University of Salamanca) and S. Moreno (IBFG, CSIC/University of Salamanca) for strains and plasmids. This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitivity (grant numbers BFU2012-30787 and BFU2015-69709-P to AB and MS).

Footnotes

Author Contributions V.A., L.V. and A.B. conceived the study and analysed the data with critical inputs from A.G.-S. and M.S. Experiments were conducted by V.A., L.V., A.G.-S., S.A., M.S. and A.B. wrote the paper and all authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Mailand N., Gibbs-Seymour I. & Bekker-Jensen S. Regulation of PCNA-protein interactions for genome stability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 269–282 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergink S. & Jentsch S. Principles of ubiquitin and SUMO modifications in DNA repair. Nature 458, 461–467 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich H. D. Regulating post-translational modifications of the eukaryotic replication clamp PCNA. DNA Repair 8, 461–469 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen P. L., Xu F. & Xiao W. Eukaryotic DNA damage tolerance and translesion synthesis through covalent modifications of PCNA. Cell Res. 18, 162–173 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang D. J. & Cimprich K. A. DNA damage tolerance: when it’s OK to make mistakes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 82–90 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D. & Foiani M. Maintaining genome stability at the replication fork. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 208–219 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Sánchez A., Conde F., San Segundo P. & Bueno A. Control of PCNA deubiquitylation in yeast. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 104–109 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich H. D. & Takahashi T. Readers of PCNA modifications. Chromosoma 122, 259–274 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugar I., Ortiz-Bazán M. Á. & Tercero J. A. Tolerating DNA damage during eukaryotic chromosome replication. Exp. Cell Res. 329, 170–177 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T. T. et al. Regulation of monoubiquitinated PCNA by DUB autocleavage. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 339–347 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Sánchez A., Andrés S., Conde F., San-Segundo P. A. & Bueno A. Reversal of PCNA ubiquitylation by Ubp10 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Plos Genet. 8, e1002826 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. M. et al. Modification of PCNA by ISG15 plays a crucial role in termination of error-prone translesion DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell 54, 626–638 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niimi A. et al. Regulation of proliferating cell nuclear antigen ubiquitination in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 16125–16130 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oestergaard V. H. et al. Deubiquitination of FANCD2 is required for DNA crosslink repair. Mol. Cell 28, 798–809 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S., Niimi A. & Lehmann A. R. Ubiquitination and deubiquitination of PCNA in response to stalling of the replication fork. Cell Cycle 8, 689–692 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannouche P. L., Wing J. & Lehmann A. R. Interaction of human DNA polymerase eta with monoubiquitinated PCNA: a possible mechanism for the polymerase switch in response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell 14, 491–500 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannouche P. L. & Lehmann A. R. Ubiquitination of PCNA and the polymerase switch in human cells. Cell Cycle 3, 1011–1013 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. M. et al. Inactivation of murine Usp1 results in genomic instability and a Fanconi anemia phenotype. Dev. Cell 16, 314–320 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouranti I. et al. A global census of fission yeast deubiquitinating enzyme localization and interaction networks reveals distinct compartmentalization profiles and overlapping functions in endocytosis and polarity. Plos Biol. 8, e1000471 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frampton J. et al. Postreplication repair and PCNA modification in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 2976–2985 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A. A., Huttner D., Daigaku Y., Chen S. & Ulrich H. D. Activation of ubiquitin-dependent DNA damage bypass is mediated by replication protein a. Mol. Cell 29, 625–636 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Sánchez A., Ufano S., Andrés S. & Bueno A. Analysis of the tolerance to DNA alkylating damage in MEC1 and RAD53 checkpoint mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Plos One 8, e81108 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva G. M., Finley D. & Vogel C. K63 polyubiquitination is a new modulator of the oxidative stress response. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 116–123 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.-G., Baek K., Soetandyo N. & Ye Y. Reversible inactivation of deubiquitinases by reactive oxygen species in vitro and in cells. Nature Communications 4, 1568 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash L. Characterization of postreplication repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and effects of rad6, rad18, rev3 and rad52 mutations. Mol. Gen. Genet. 184, 471–478 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangavarapu V., Prakash S. & Prakash L. Requirement of RAD52 group genes for postreplication repair of UV-damaged DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 7758–7764 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S. et al. Homologous recombination restarts blocked replication forks at the expense of genome rearrangements by template exchange. Mol. Cell 39, 346–359 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Prieto R., Muñoz-Cabello A. M., Cabello-Lobato M. J. & Prado F. Rad51 replication fork recruitment is required for DNA damage tolerance. EMBO J. 32, 1307–1321 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulon S. et al. Rad8Rad5/Mms2-Ubc13 ubiquitin ligase complex controls translesion synthesis in fission yeast. EMBO J. 29, 2048–2058 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoege C., Pfander B., Moldovan G.-L., Pyrowolakis G. & Jentsch S. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature 419, 135–141 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelter P. & Ulrich H. D. Control of spontaneous and damage-induced mutagenesis by SUMO and ubiquitin conjugation. Nature 425, 188–191 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haracska L., Torres-Ramos C. A., Johnson R. E., Prakash S. & Prakash L. Opposing effects of ubiquitin conjugation and SUMO modification of PCNA on replicational bypass of DNA lesions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 4267–4274 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K. et al. Rad18 guides poleta to replication stalling sites through physical interaction and PCNA monoubiquitination. EMBO J. 23, 3886–3896 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Z. et al. Regulation of polymerase exchange between Poleta and Poldelta by monoubiquitination of PCNA and the movement of DNA polymerase holoenzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 5361–5366 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosbech A. et al. DVC1 (C1orf124) is a DNA damage-targeting p97 adaptor that promotes ubiquitin-dependent responses to replication blocks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 1084–1092 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou K. P. et al. Systems-wide analysis of ubiquitylation dynamics reveals a key role for PAF15 ubiquitylation in DNA-damage bypass. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 1089–1098 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S., Johnson R. E. & Prakash L. Eukaryotic translesion synthesis DNA polymerases: specificity of structure and function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 317–353 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D. & Foiani M. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 297–308 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannattasio M. et al. Visualization of recombination-mediated damage bypass by template switching. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 884–892 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumasoni M., Zwicky K., Vanoli F., Lopes M. & Branzei D. Error-free DNA damage tolerance and sister chromatid proximity during DNA replication rely on the Polα /Primase/Ctf4 Complex. Mol. Cell 57, 812–823 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indiani C., Langston L. D., Yurieva O., Goodman M. F. & O’donnell M. Translesion DNA polymerases remodel the replisome and alter the speed of the replicative helicase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 6031–6038 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yuan Z. & Zhang Z. The cellular robustness by genetic redundancy in budding yeast. Plos Genet. 6, e1001187 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigaku Y., Davies A. A. & Ulrich H. D. Ubiquitin-dependent DNA damage bypass is separable from genome replication. Nature 465, 951–955 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karras G. I. & Jentsch S. The RAD6 DNA damage tolerance pathway operates uncoupled from the replication fork and is functional beyond S phase. Cell 141, 255–267 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Bazán M. Á. et al. Rad5 Plays a Major Role in the Cellular Response to DNA Damage during Chromosome Replication. Cell Reports (2014), doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S., Klar A. & Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Meth Enzymol 194, 795–823 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsburg S. L. & Rhind N. Basic methods for fission yeast. Yeast 23, 173–183 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cueille N. et al. Flp1, a fission yeast orthologue of the s. cerevisiae CDC14 gene, is not required for cyclin degradation or rum1p stabilisation at the end of mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 114, 2649–2664 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Cuervo H. & Bueno A. Cds1 controls the release of Cdc14-like phosphatase Flp1 from the nucleolus to drive full activation of the checkpoint response to replication stress in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2488–2499 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban V. et al. A role for the Cdc14-family phosphatase Flp1p at the end of the cell cycle in controlling the rapid degradation of the mitotic inducer Cdc25p in fission yeast. J. Cell. Sci. 117, 2461–2468 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban V., Sacristán M., Andrés S. & Bueno A. The Flp1/Clp1 phosphatase cooperates with HECT-type Pub1/2 protein-ubiquitin ligases in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cell Cycle 7, 1269–1276 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine M. S. et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14, 953–961 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen W., Meinkoth J. L., Tsien R. Y. & Taylor S. S. Identification of a signal for rapid export of proteins from the nucleus. Cell 82, 463–473 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgington N. P. & Futcher B. Relationship between the function and the location of G1 cyclins in S. cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 114, 4599–4611 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodel A. E. et al. Nuclear localization signal receptor affinity correlates with in vivo localization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 23545–23556 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossio V. & Yoshida S. Spatial regulation of Cdc55-PP2A by Zds1/Zds2 controls mitotic entry and mitotic exit in budding yeast. J. Cell. Biol. 193, 445–454 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhese M. P. et al. The novel DNA damage checkpoint protein ddc1p is phosphorylated periodically during the cell cycle and in response to DNA damage in budding yeast. EMBO J. 16, 5216–5226 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordon-Preciado V., Ufano S. & Bueno A. Limiting amounts of budding yeast Rad53 S-phase checkpoint activity results in increased resistance to DNA alkylation damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 5852–5862 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bähler J. & Pringle J. R. Pom1p, a fission yeast protein kinase that provides positional information for both polarized growth and cytokinesis. Genes Dev. 12, 1356–1370 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodovsky A. et al. A novel active site-directed probe specific for deubiquitylating enzymes reveals proteasome association of USP14. EMBO J. 20, 5187–5196 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.