Abstract

In this study we established the B1 and B12 vitamin requirement of the dinoflagellate Lingulodinium polyedrum and the vitamin supply by its associated bacterial community. In previous field studies the B1 and B12 demand of this species was suggested but not experimentally verified. When the axenic vitamin un-supplemented culture (B-ns) of L. polyedrum was inoculated with a coastal bacterial community, the dinoflagellate’s vitamin growth limitation was overcome, reaching the same growth rates as the culture growing in vitamin B1B7B12-supplemented (B-s) medium. Measured B12 concentrations in the B-s and B-ns cultures were both higher than typical coastal concentrations and B12 in the B-s culture was higher than in the B-ns culture. In both B-s and B-ns cultures, the probability of dinoflagellate cells having bacteria attached to the cell surface was similar and in both cultures an average of six bacteria were attached to each dinoflagellate cell. In the B-ns culture the free bacterial community showed significantly higher cell abundance suggesting that unattached bacteria supplied the vitamins. The fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) protocol allowed the quantification and identification of three bacterial groups in the same samples of the free and attached epibiotic bacteria for both treatments. The relative composition of these groups was not significantly different and was dominated by Alphaproteobacteria (>89%). To complement the FISH counts, 16S rDNA sequencing targeting the V3–V4 regions was performed using Illumina-MiSeq technology. For both vitamin amendments, the dominant group found was Alphaproteobacteria similar to FISH, but the percentage of Alphaproteobacteria varied between 50 and 95%. Alphaproteobacteria were mainly represented by Marivita sp., a member of the Roseobacter clade, followed by the Gammaproteobacterium Marinobacter flavimaris. Our results show that L. polyedrum is a B1 and B12 auxotroph, and acquire both vitamins from the associated bacterial community in sufficient quantity to sustain the maximum growth rate.

Keywords: B vitamin auxotrophy, dinoflagellate–bacteria interactions, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), 16S rDNA, Illumina-MiSeq sequencing

Introduction

Culture-based (Tang et al., 2010) and field studies (Bertrand et al., 2007; Gobler et al., 2007; Koch et al., 2011, 2012) have supported long standing hypothesis that vitamin availability can have an impact on phytoplankton growth and community composition (Droop, 2007). A majority of eukaryotic phytoplankton requires exogenous B vitamins, hence being B vitamin auxotroph. They are lacking the biosynthetic pathways to produce them or alternative pathways to bypass the need for the vitamin as in the case of B12. Of the examined species 54% required vitamin B12 (cobalamin; hereafter B12), 27% required vitamin B1 (thiamine; hereafter B1) and 8% required vitamin B7 (biotin; hereafter B7) (Tang et al., 2010). B12 is essential for the synthesis of amino acids, deoxyriboses, and the reduction and transfer of single carbon fragments in many biochemical pathways. B1 plays a pivotal role in intermediary carbon metabolism and is a cofactor for a number of enzymes involved in primary carbohydrate and branched-chain amino acid metabolism. B7 is a cofactor for several essential carboxylase enzymes, including acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) carboxylase, which is involved in fatty acid synthesis, and so is universally required (Croft et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2010).

Dinoflagellates are among the most abundant eukaryotic phytoplankton in freshwater and coastal systems (Moustafa et al., 2010). Of the 45 examined dinoflagellate species, those species involved in harmful algal bloom events, 100% required B12, 78% B1 and 32% B7 (Tang et al., 2010). Available genomic data indicate that some heterotrophic bacteria and archaea, as well marine cyanobacteria are vitamin producers (Bonnet et al., 2010; Sañudo-Wilhelmy et al., 2014). Many dinoflagellates are mixotrophs (Burkholder et al., 2008), therefore they could acquire their B vitamins from the environment either through phagotrophy (Jeong et al., 2005), active uptake from the soluble fraction (Bertrand et al., 2007; Kazamia et al., 2012) or through episymbiosis (Croft et al., 2005; Wagner-Döbler et al., 2010; Kazamia et al., 2012; Kuo and Lin, 2013; Xie et al., 2013). The relative contribution of these different mechanisms to vitamin acquisition of dinoflagellates is not known but could help in the understanding of dinoflagellate ecology and the possible role of vitamins in bloom development.

Lingulodinium polyedrum is a dinoflagellate with a mixotrophic lifestyle (Jeong et al., 2005) that is recurrently forming blooms along the coast of southern California and northern Baja California (Peña-Manjarrez et al., 2005). Although its physiology (Hastings, 2007; Beauchemin et al., 2012) and microbial ecology (Mayali et al., 2008, 2010, 2011) have been previously studied, its vitamin auxotrophy has only been inferred from oceanographic observations (Carlucci, 1970), but has not been experimentally established. Here we investigate the role of vitamins and bacteria in the autecology of L. polyedrum, using axenic and non-axenic cultures of L. polyedrum under different combinations of multiple and single vitamin limitation.

To document the association of a natural bacterial community in L. polyedrum cultures under B1B7B12-supplemented (hereafter B-s) and B1B7B12-not supplemented (hereafter B-ns) cultures, we employed a FISH and digital imaging approach to quantify free and attached bacteria, and 16S rDNA sequencing targeting V3–V4 regions looking for phylogenetic composition. To complement the information on the B12 synthesis, we quantified the B12 in both vitamin amendments.

Materials and Methods

Strain and Growth Conditions

Coastal seawater was collected off Ensenada (31.671° N, 116.693° W; Ensenada, México) treated with activated charcoal, filtered through GF/F, and 0.22-mm pore-size cartridge filter (Pall corporation) and stored in the dark at room temperature to age for at least 2 months. Aged seawater was sparged with CO2 (5 min per 1 L of seawater), autoclaved for 15 min and then equilibrated with air. Non-axenic L. polyedrum HJ culture (Latz Laboratory, UCSD-SIO) was grown in L1 medium (National Center for Marine Algae and Microbiota, Boothbay, ME, USA) prepared with aged oceanic water under 12:12 h light/dark cycle at an irradiance level of 100 μmol m2 s–1 and a temperature of 20°C. To make the culture axenic, L. polyedrum cultures were incubated with 1 ml of antibiotic solution (Penicillin, 5,000 U; Streptomycin, 5 mg ml–1; Neomycin, 10 mg ml–1. Sigma–Aldrich, P4083-100ML) for 50 ml of culture during 24 h, rinsed with L1 medium, and repeated three times each step. Bacterial presence in the L. polyedrum culture was checked by staining with the nucleic acid-specific stain 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI,1 μg ml–1) and quantification using epifluorescence microscopy (Axioskope II plus, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) connected by liquid light guide to a 175 W xenon arc lamp (Lambda LS, Sutter), with optical filtering (Excitation, 360 nm/Dichroic, 395 nm / Emission, >397 nm; Semrock and Zeiss) under X100 objective lens (Plan-Apochromat, Carl Zeiss). The axenic status was declared when after three antibiotic rounds and sterile medium washes we could not detect bacteria in the culture through epifluorescence microscopy. Semi-continuous cultures were transferred approximately weekly using 10 × dilutions.

Qualitative Assessment of B1, B7, and B12 Dinoflagellate Auxotrophy

Bacteria are a potential source of B1, B7, and B12, making it necessary to establish axenic cultures before testing vitamin auxotrophy. To test the vitamin auxotrophic status of L. polyedrum, cultures (n = 3) were grown semi-continuously in 15 ml glass test tubes with silicon stoppers. Cultures were acclimated by five semi-continuous transfers during 5 weeks. The medium for L. polyedrum axenic cultures was supplemented either with the L1 vitamin mix (B1, 296000; B7, 2050; B12, 370; pmol L–1), or with the following combinations of vitamins, B1+B12, B1+B7, and B7+B12 at the same concentration (B1, Sigma–Aldrich; B7, Sigma–Aldrich; B12, Sigma–Aldrich). Cell growth rate was monitored by mixing first the cultures with an inclined rotating test tube holder (10 rpm) before measuring in vivo chlorophyll a fluorescence using a Turner Designs 10-000 fluorometer at the midpoint of the light phase. The specific growth rate (μ) was estimated according to the equation μ = ln(N2/N1)/(t2–t1): where N1 and N2 was in vivo chlorophyll a fluorescence in relative units (r. u.) at time 1 (t1) and time 2 (t2) respectively. Vitamin auxotrophy was declared when a culture ceased to grow in the absence of vitamins while growth persisted in parallel control treatments with added vitamin.

Qualitative Assessment of B1 and B12 Synthesis from the Bacterial Community

The axenic L. polyedrum culture (n = 3) was inoculated with a prokaryotic community obtained by filtering (0.8 μm polycarbonate filter) rocky intertidal seawater (31.861755 °N, 116.668097°W; Ensenada, México). L. polyedrum culture lines were divided into B-s and B-ns cultures, and acclimated by culture transfer for 6 months to ensure depletion of the initial vitamin present and to be sure that the persisting microbial community had the potential to synthesize vitamins. The specific growth rate was monitored as described above, taking the day eight as t2 and day zero as t1.

Cell Fixation, Immobilization, and Embedding

Five mililiter of L. polyedrum cells from B-s and B-ns cultures were harvested at lag, exponential and stationary phase and fixed with paraformaldehyde-PBS at a final concentration of 1% for 12 h at 4°C. For attached bacteria, fixed cells were immobilized onto an 8.0 μm pore size, 25 μm-diameter Nucleopore filter (Whatman International, Ltd., Maidstone, England) using a pressure difference of <3.3 kPa to avoid cell disintegration, and rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS,0.1 M NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 4 mM Na2HPO4, pH 8.1; Palacios and Marín, 2008). For free-living bacteria, the fraction which passed through 8.0 μm pore size filter was collected on 0.2 μm pore size, 25 mm-diameter Nucleopore filter (Whatman International, Ltd., Maidstone, England) and rinsed with PBS. The cells collected on the 8.0 μm filter were covered with 13 μl of low-melting point agarose (0.05%, LMA) (BioRad, 161-3111) at 55°C, dried for 15 min at 37°C, then LMA was added again and the filter dried as previously.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

All in situ hybridizations were performed as described in Cruz-López and Maske (2014). In brief, before hybridization, bacterial cells were partially digested with 400,000 U ml–1 lysozyme (Sigma, L6876) dissolved in buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 for 1 h at 37°C. The enzyme reaction was stopped by rinsing the filter three times with 5 ml sterile water for 1 min at 4°C. Fixed and embedded samples were hybridized with a buffer containing 900 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.02% SDS, pH 8.0. When probes with different stringency optima were applied to the same sample, sequential hybridization was performed, beginning with the probes requiring the most stringent conditions. Probes and hybridization conditions are listed in Table 1. Hybridizations containing 1 μl of probe for every 20 μl of buffer (final probe concentration = 25 ng μl–1) were performed at 46°C for 2 h. After this, filters were washed with pre-warmed (48°C) buffer (900 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.02% SDS, 5 μM EDTA) for 15 min and rinsed for 5 min in distilled H2O. To be able to localize the theca and bacterial cells, we used Calcofluor (Sigma-Aldrich, México City, México) (1 μg ml–1) and for DNA staining 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI Molecular Probes) (1 μl ml–1), incubating 5 min in the dark at room temperature. Filters were rinsed twice with sterile H2O for 5 min, dried and mounted in antifade reagent (Patel et al., 2007) and covered with cover slip.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide probes used in this study.

| Probe | Target group | Sequence (5′-3′) | Target sitea | % Formamide in ISHb buffer | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUB338 | Bacteria | GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT | 16S (338–355)c | 0–50 | Amann et al., 1990 |

| NON338 | Negative control | ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGC | 16S (338–355)c | Amann et al., 1990 | |

| ALF968 | Alphaproteobacteria | GGTAAGGTTCTGCGCGTT | 16S (968–986)e | 20 | Glöckner et al., 1999 |

| CF319a | Bacteroidetes | TGGTCCGTGTCTCAGTAC | 16S (319–336)d | 35 | Manz et al., 1996 |

| GAM42a | Gammaproteobacteria | GCCTTCCCACATCGTTT | 23S (1027–1043)c | 35 | Glöckner et al., 1999 |

aE. coli numbering; bIn situ hybridization; cCy3; dATTO425; eAlexa594.

Visualization

The epifluorescence microscope (Axioskope II plus, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany; oil immersion X100 objective, Plan-Apochromat, Carl Zeiss; 175 W xenon arc lamp; Lambda LS, Sutter connected through a liquid light guide) was used with a triple Sedat filter, a dichroic filter with three transmission bands. Excitation and emission spectra were controlled by filter wheels (Lambda 10-3, Sutter). Images were captured with a cooled CCD camera (Clara E, Andor) with 10 ms integration time. Optical stacks, 2.0 μm focal distance between images, were acquired with a computer controlled focusing stage (Focus Drive, Ludl Electronic Products, Hawthorne, NY, USA) and Micro-Manager (version 1.3.40, Vale Lab, UCSF) that controlled filter selection and the focusing stage. The images were processed in ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012). For each spectral channel a summary image was composed by selecting the pixels of maximum intensity within the stack, and using the ‘Find Edges’ and ‘Despeckle’ functions to reduce images noise (Cruz-López and Maske, 2014).

16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing

The free and attached bacterial communities from B-s and B-ns cultures were characterized and compared using barcoded high-throughput amplicon sequencing of the bacterial 16S rDNA. Four samples with no replicates were sequenced: (1) 50 ml of L. polyedrum cells from B-s and B-ns cultures were harvested at mid-exponential phase, and pre-filtered with (a) 8.0 μm pore size, 47 mm-diameter Nucleopore filter (Whatman International, Ltd., Maidstone, England) using a pressure difference of <3.3 kPa to avoid cell disintegration, with a second filtration step with (b) 0.4 μm pore size, 47 mm-diameter polycarbonate filter (Whatman International, Ltd., Maidstone, England) to recover the free-bacterial fraction, and (2) The first filter (a) containing the dinoflagellate cells were treated with 10 mM N-acetyl cysteine (NAC; Sigma) (PBS – 0.2 μM calcium chloride, 0.5 mM magnesium chloride, 15 mM glucose) for 1 h with agitation (70 rpm) at room temperature to detach adhered bacteria (Barr et al., 2013). The detached bacterial cells were collected onto a 0.4 μm pore size, 47 mm-diameter polycarbonate filter. Filters containing both free and detached bacterial communities were processed by the Research and Testing Laboratory (RTL, Lubbock, TX, USA), including DNA extraction. The bacterial hypervariable regions V3-V4 of the 16S rRNA gene were PCR amplified using the forward 341F (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) and the reverse 805R (GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC) primers set (Herlemann et al., 2011) followed by sequencing on the MiSeq platform (Illumina Inc., USA). MiSeq reads were quality checked and paired reads joined using PEAR (Zhang et al., 2013), dereplicated using USEARCH (Edgar, 2010), OTU selected using UPARSE (Edgar, 2013) and chimera checked using UCHIME (Edgar et al., 2011) executed in de novo mode. Generated sequences then were run against the RDP classifier employing the NCBI database. All downstream analysis were done in the RTL facility using their standard pipeline. The MiSeq reads have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive with accession number SRP071004.

Dissolved B12 Quantification

B12 was quantified during the mid-exponential phase in non-axenic B-s and B-ns cultures. Twenty mililiter of L. polyedrum cultures were harvested, and pre-filtered with 8.0 μm pore size, followed by a filtration step with 0.45 μm pore size, both 47 mm-diameter Nucleopore filter (Whatman International, Ltd., Maidstone, England) using a pressure difference of <3.3 kPa to avoid cell disintegration. B12 was pre-concentrated by solid phase (RP-C18) extraction according to Okbamichael and Sañudo-Wilhelmy (2004), the column was eluted with 5 ml methanol, the methanol was evaporated at 60°C with vacuum, and 50 μl of the concentrate was injected into the ELISA well plate for quantification (Immunolab GmbH, B12-E01. Kassel, Germany) according to Zhu et al. (2011).

Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA was used to compare growth rate curves of L. polyedrum under B-s and B-ns cultures, and to compare the B12 synthesis from both bacterial communities. Since the distribution of the number of attached bacteria per dinoflagellate cell was not normal, a Kruskal–Wallis test was used to assess the significance (α = 0.05) in the number of attached bacterial during the L. polyedrum growth curve. All analysis were performed using the STATISTICA 7.1v software (Stat Soft Inc., USA).

Results

Lingulodinium polyedrum Auxotrophy for B Vitamins

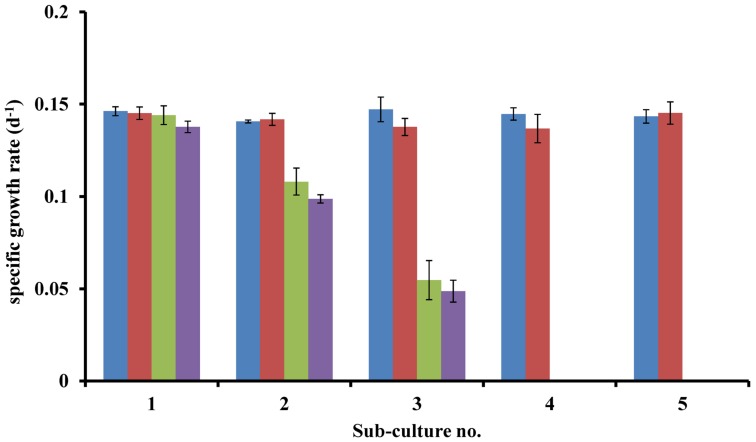

Lingulodinium polyedrum was grown axenically with (B-s) and without (B-ns) adding the L1 vitamin mix. B-s cultures continued growing after five subcultures, B-ns cultures started to show slower growth rates after one transfer, but only after the third transfer, the B-ns cultures stopped growing. To establish which B vitamins were limiting the growth of L. polyedrum we prepared cultures containing (B1B7B12), (B1B12), (B1B7) and (B7B12). Under B1B7B12-s condition, cultures continued growing after five subcultures. In the B1B12-s condition cultures showed the same growth rate as the B1B7B12-s condition, whereas in B1B7-s and B7B12-s condition, the cultures ceased to grow. These experiments were repeated three times with the same result (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Specific growth rates of axenic L. polyedrum grown in: ( ) B1B7B12-s; (

) B1B7B12-s; ( ) B1B12-s; (

) B1B12-s; ( ) B1B7-s; (

) B1B7-s; ( ) B7B12-s cultures.

) B7B12-s cultures.

Co-Culture of L. polyedrum with a Natural Bacterial Community

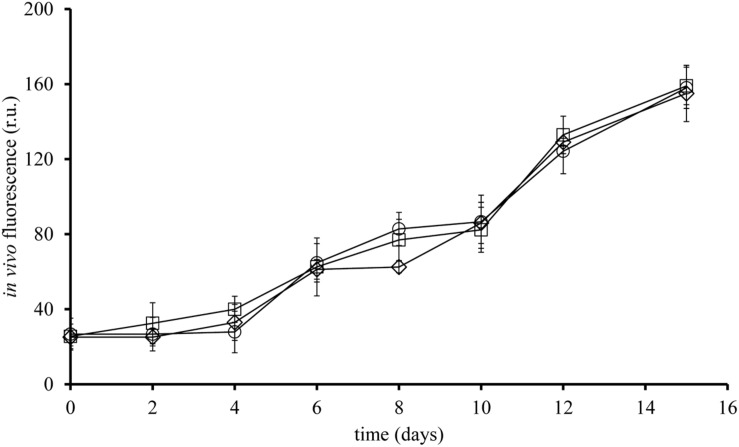

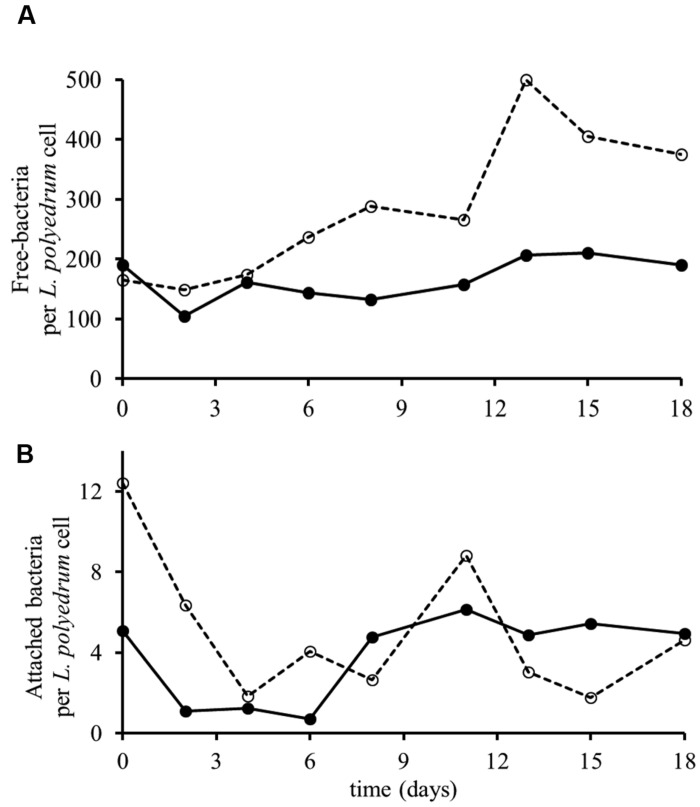

Non-axenic L. polyedrum culture in B-ns condition could maintain growth through more than five culture transfers at growth rates similar (p > 0.05) to the axenic and the non-axenic, B-s cultures (Figure 2). These results suggest that the bacteria in the non-axenic culture could provide sufficient amounts of vitamins to sustain L. polyedrum growth. In the non-axenic cultures the concentration of freely suspended bacteria in the B-ns culture was significantly higher than in the B-s culture (p < 0.05; Figure 3A, Supplementary Figure S1). The mean number of attached bacteria ranged from 1 to 6 in B-s culture and from 1 to 12 in B-ns culture; in both types of non-axenic cultures the probability of L. polyedrum cells to have bacteria attached or the average number of bacteria attached to L. polyedrum cells were not significantly different (p > 0.05; Figure 3B).

FIGURE 2.

Growth curve of L. polyedrum, axenic or in co-culture with a natural marine bacterial community. (□) axenic, B-s; (○) non-axenic, B-ns; (♢) non-axenic, B-ns. Each curve is the results of three culture replicates with the standard deviation indicated by vertical bars.

FIGURE 3.

Growth of L. polyedrum and associated bacteria culture under B-s (–•–) and B-ns (–○–) conditions. (A) Ratio of freely suspended bacteria to L. polyedrum cells. (B) Average number of bacteria attached to those L. polyedrum cells that had at least one bacteria attached. n = 50 dinoflagellate cells.

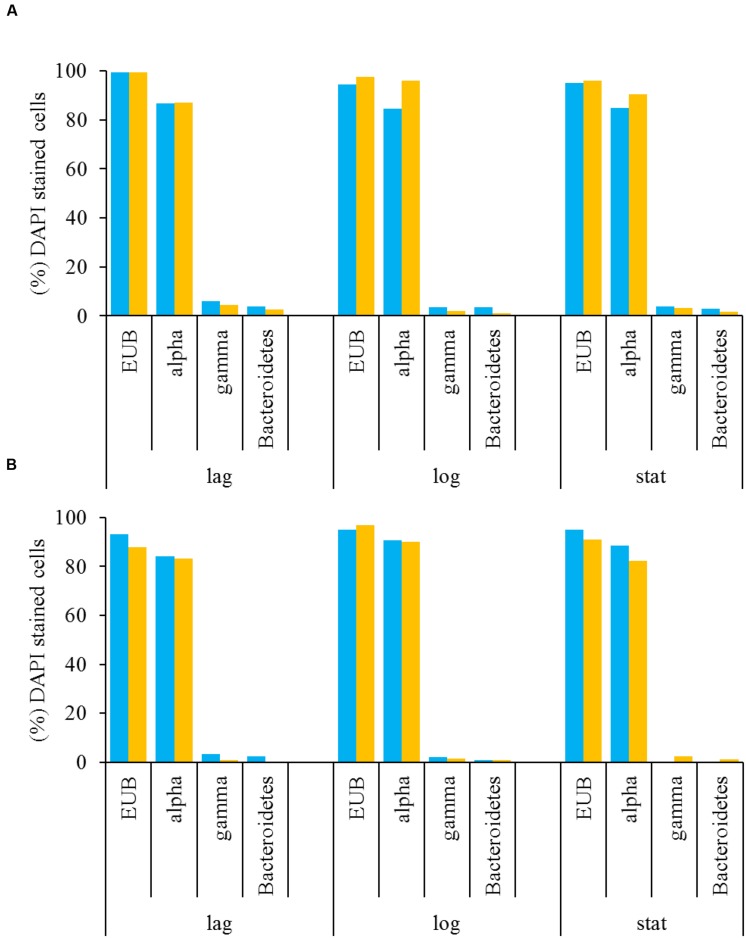

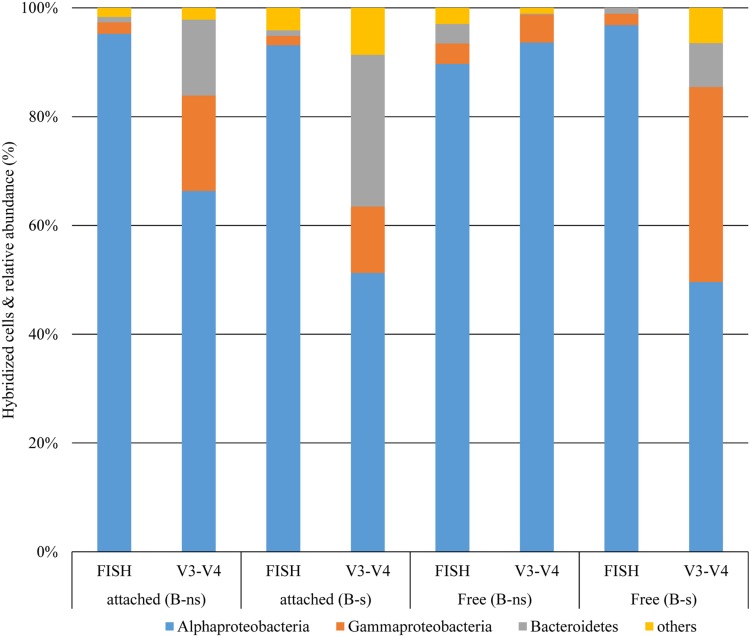

Free and Attached Bacterial Community by FISH

A multiprobe FISH protocol was used to identify the major bacterial groups in L. polyedrum cultures that were either freely suspended or attached to the host cells (Cruz-López and Maske, 2014). These results showed that Alphaproteobacteria were abundant in the free and attached fractions of B-s and B-ns cultures. In both vitamin treatments Alphaproteobacteria comprised on average 80% of the bacterial community, while Gammaproteobacteria and Bacteroidetes were scarcely detected (Figures 4A,B). As stated in Biegala et al. (2002) when working with phytoplankton it is critical to use group-specific probes to discriminate the false positives coming from the plastids. In our samples we could discriminate the eubacterial probe (EUB338) from the group-specific probes this allowed us to confirm the group specific probes with bacteria attached to L. polyedrum cells.

FIGURE 4.

Free-living (A) and attached (B) bacteria associated with L. polyedrum in B-ns ( ) and B-s (

) and B-s ( ) cultures during different culture phases (lag, mid-exponential and stationary phases) given in percentages of the total number of DAPI-stained cells. Specific bacterial groups were quantified by FISH hybridized with the four probes listed in Table 1.

) cultures during different culture phases (lag, mid-exponential and stationary phases) given in percentages of the total number of DAPI-stained cells. Specific bacterial groups were quantified by FISH hybridized with the four probes listed in Table 1.

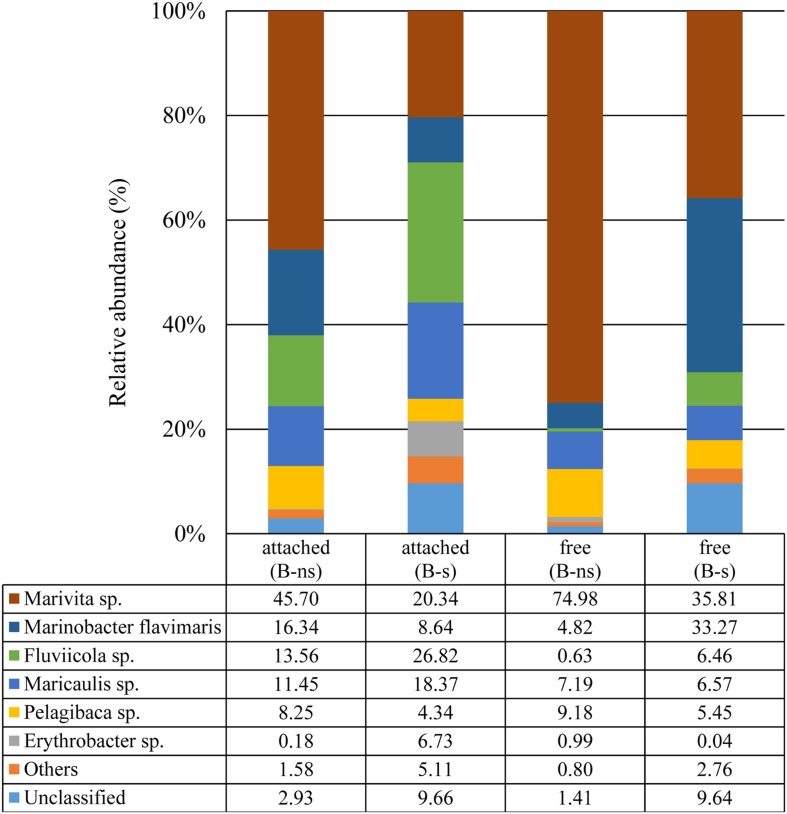

Free and Attached Bacterial Community by 16S Amplicons

We assessed the relative abundance of bacterial taxa at the level of phylum, class, genus and species for each sample. Four samples with no replicates were sequenced: the attached and the free living bacterial community of B-s and B-ns cultures.

In the B-s culture, most of the free-bacterial community reads were assigned to the class Alphaproteobacteria (49.6%), with Marivita sp. as the dominant species (35.8%), followed by Maricaulis sp. (6.5%) and Pelagibaca sp. (5.4%). The class Gammaproteobacteria represented 35.8%, with Marinobacter flavimaris as the dominant species (33.2%). Other phyla presented were Actinobacteria, Planctomycetes, Cyanobacteria and Firmicutes representing the 2.76%, while the unclassified reads represented the 9.64% (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Taxonomic classification of bacterial 16S rDNA (V3–V4) Illumina reads at species level.

In the B-ns culture, most of the free-bacterial community reads were assigned to the class Alphaproteobacteria comprising 93.6% of the detected sequences, with Marivita sp. as the dominant species in the sample (74.9%) followed by Pelagibaca sp. (9.1%), Maricaulis sp. (7.1%). The class Gammaproteobacteria represented 5.1%, dominated by Marinobacter flavimaris (4.8%). Other phyla presented were Actinobacteria, Planctomycetes, Cyanobacteria and Firmicutes representing less than 1%, while the unclassified reads represented the 1.4% (Figure 5)

In the B-s culture, even though the attached bacterial community was dominated by the Alphaproteobacteria (51.2%), the dominant species was the Bacteroidetes Flaviicola sp. (26.8%), followed by the Alphaproteobacteria Marivita sp. (20.3%), Maricaulis sp. (18.3%), Erythrobacter sp. (6.7%), Pelagibaca sp. (4.3%), and the Gammaproteobacteria Marinobacter flavimaris (8.6%). Other phyla presented were Planctomycetes, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes and Cyanobacteria representing 5.11% of the reads, while the unclassified reads represented 9.6% (Figure 5).

In the B-ns culture, the attached community was dominated by the class Alphaproteobacteria (66.3%), the dominant observed species were the Alphaproteobacteria Marivita sp. (45.7%), the Gammaproteobacteria Marinobacter flavimaris (16.3%), and the Bacteroidetes Flaviicola sp. (13.5%) (Figure 5) followed by the alphaproteobacterial species Maricaulis sp. (11.4%) and Pelagibaca sp. (8.2%) (Figure 5). Other phyla presented were Planctomycetes, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes and Cyanobacteria representing 1.58% of the reads, while the unclassified reads represented 2.9% (Figure 5).

Dissolved B12 Quantification

After 5 days during the mid-exponential phase, we quantified B12 in B-s and B-ns cultures; our results show that the synthesis of B12 from the microbial community varies between conditions. The initial B12 concentration in the L1 medium is 370 pmol L–1 (Guillard, 1975). In our cultures, we quantified the B12 during the exponential phase, in the B-s culture, the B12 was 26.3 ± 2.8 pmol L–1 (n = 3), and in the B-ns culture was 14.4 ± 7.6 pmol L–1 (n = 3).

In both cases, the differences of B12 in the cultures (p < 0.05) are the balance between the consumption of the L. polyedrum population and the synthesis and excretion from the microbial community. The vitamin mix of the L1 medium includes B1 and B7, and below we only discuss B12 because we could quantify its concentration.

Discussion

Lingulodinium polyedrum and Vitamin Auxotrophy

Phytoplankton vitamin B auxotrophy has been previously observed in cultures (reviewed by Droop, 2007) and in natural phytoplankton assemblages in coastal areas (Sañudo-Wilhelmy et al., 2006: Gobler et al., 2007; Koch et al., 2012). Here we address vitamin auxotrophy of L. polyedrum and its vitamin supply by natural bacterial communities. L. polyedrum was chosen because it forms coastal red tides and because previous studies had demonstrated high bacterial abundance and diversity of attached bacteria (Fandino et al., 2001; Mayali et al., 2011). Carlucci (1970) interpreted phytoplankton and B12 data from coastal waters of S. California and concluded that L. polyedrum was B12 auxotroph, but L. polyedrum vitamin B auxotrophy has not been previously tested experimentally. In our axenic cultures the sequential transfer into vitamin B free media led to a continuous reduction in growth rates until growth stopped. The continued growth of the first subcultures was probably supported by the vitamin present in the inoculum used for culture transfer, either in the medium or intracellularly. Further culture experiments demonstrated B1 and B12 auxotrophy of L. polyedrum (Figure 1) similar to what has been reported for other dinoflagellate species (Tang et al., 2010). B1 and B12 behaved like independent limiting factors, both vitamins were necessary to support growth.

Lingulodinium polyedrum is expected to be mixotrophic, potentially allowing for different modes of vitamin uptake; through osmotrophy, phagotrophy (Jeong et al., 2005) or through the episymbiosis with heterotrophic bacteria attached to cells (Croft et al., 2005). In our cultures the probability of bacterial attachment to L. polyedrum cells and the number of attached bacteria was not significantly different in B-ns and B-s cultures of L. polyedrum which argues against episymbiosis. The ratio of freely suspended bacteria to L. polyedrum cells did significantly increase in B-ns cultures, suggesting that vitamins for L. polyedrum growth were provided by part of the free bacterial community and then the dissolved vitamin was taken up by L. polyedrum and the auxotrophic part of the bacterial community.

The measured concentration of B12 in the B-ns non axenic culture was close to 50% lower than the B-s culture, but despite that, both concentrations are in the range of highly productive coastal systems (reviewed in Sañudo-Wilhelmy et al., 2014), Because culture concentrations were similar its seems probable that the B12 concentrations did not limit the L. polyedrum growth rate in culture. The concentrations in the culture without vitamin added were measured during exponential phase and represent the equilibrium concentration between the continuous supply from the bacterial consortium and the uptake by the dinoflagellate. In this case the bacterial consortium includes B12 producers and consumers with an overall B12 overproduction. It should be considered that the B-s culture received not only B12 but in addition B1 and B7. Because L. polyedrum is B1 auxotroph the addition of this vitamin might influence the outcome of the equilibrium B12 concentration.

Although we found no increase in bacteria attached to L. polyedrum, the interaction between the free-bacterial community and L. polyedrum still constitute a form of symbiosis between vitamin producing bacteria in suspension and L. polyedrum where the latter provides the labile organics to the media to sustain the growth of the suspended bacteria. We did not measure dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in the culture medium but the medium was prepared from aged seawater and no DOC was added by us. Our data do not exclude the possibility of vitamin acquisition by either episymbiosis or phagocytosis, but we found no microscopic evidence for phagocytosis. We considered episymbiosis to be unlikely because of similar numbers and phylogenetic composition of attached bacteria, but attached epibionts could still contribute to the B12 supply (Wagner-Döbler et al., 2010).

Free and Attached Bacterial Community by FISH

The selected probes used for FISH analysis were based on available probes for bacteria associated with dinoflagellates. This method identified Alphaproteobacteria as the dominant bacterial group in the attached and freely suspended bacterial community in B-s and B-ns cultures (Figures 4A,B). It is difficult to relate the dominance observed in this study to particular functional phenotypes, because the Alphaproteobacteria are metabolically diverse (Luo and Moran, 2014). However, recent evidence indicates that the Alphaproteobacteria could contribute with B1 and B12 to their dinoflagellate host (Wagner-Döbler et al., 2010). The Roseobacter clade is an important marine Alphaproteobacteria lineage associated with dinoflagellates (Fandino et al., 2001; Hasegawa et al., 2007; Mayali et al., 2008, 2011) and includes species that produce B1 and B12 (Wagner-Döbler et al., 2010). Bacteria within this clade are known to be epibionts of dinoflagellates, including L. polyedrum (Mayali et al., 2011) and can represent the most abundant group within the bacterial assemblages associated with phytoplankton cultures and during bloom conditions (Fandino et al., 2001; Hasegawa et al., 2007).

We also identified Gammaproteobacteria and Bacteroidetes as less frequent epibionts. Gammaproteobacteria and Bacteroidetes have been found previously in natural samples during bloom conditions (Fandino et al., 2001; Garcés et al., 2007; Mayali et al., 2011), their low attachment frequency in our cultures is in agreement with their low abundances reported in culture and field samples (Garcés et al., 2007). Genomic data about these two groups confirm that most Gammaproteobacteria have the metabolic potential to produce B1 and B12, whereas only some Bacteroidetes possess the pathway for B1 but not for B12 (Sañudo-Wilhelmy et al., 2014).

The stable communities observed by FISH counts during the course of the culture (Figures 4A,B) suggest that Alphaproteobacteria and possibly Roseobacter clade species are an integral part of the epiphytic community of L. polyedrum. The similarity of probe frequency in attached and suspended fractions and in both vitamin amendments, suggests that bacteria of the different phylogenetic groups could move between both forms, thus, the bacterial community composition seemed more influenced by the host-specificity rather than the capacity to produce vitamins.

Free and Attached Bacterial Community by 16S Amplicons

Overall, the phylogenetic composition of the four samples was restricted to the Alphaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria classes and Bacteroidetes phylum. The Alphaproteobacteria class dominated in the free and attached bacterial fraction.

In this study, Marivita sp. was more abundant in the B-ns culture in comparison with the B-s culture, suggesting a functional association with L. polyedrum for example as B vitamin producer, or potentially as suggested in Green et al. (2015) as a growth-promoter. Wagner-Döbler et al. (2010) and Durham et al. (2015) observed other members of the Roseobacter clade to be associated with phytoplankton such as Dinoroseobacter shibae and Ruegeria pomeroyi respectively.

The second most abundant species in our samples was Marinobacter flavimaris. Marinobacter genus has been reported in association with dinoflagellates in culture (Green et al., 2004, 2006, 2015; Hatton et al., 2012). This genus is known for having a mutualistic relationship with phytoplankton as an iron siderophore producer or as a growth promoter (Amin et al., 2009; Bolch et al., 2011). During an iron-siderophore survey, M. flavimaris was isolated from different dinoflagellates species in culture but not from L. polyedrum (Amin et al., 2009). This species is phylogenetically related to M. algicola, M. adhaerens, and M. aquaeolei based on 16S rRNA sequence (Gärdes et al., 2010), however, its metabolic potential is expected to be rather different since M. algicola is known for siderophore production, M. adhaerens for the induction of marine organic matter aggregation and M. aquaeolei for its capacity to consume hydrocarbons. These different physiological profiles make it difficult to assume a metabolic potential for M. flavimaris based on the 16S rRNA gene.

In a recent study, Green et al. (2015) reported the co-occurrence of Marivita sp. and Marinobacter sp. in cultures of the coccolithophorids Emiliania huxleyi and Coccolithus pelagicus f. braarudii. In our data we have a similar co-occurrence of Marivita sp. and Marinobacter flavimaris; in the attached fraction, in the B-ns, the ratios were Marivita sp.: M. flavimaris 2.7:1, while in the B-s were 2.3:1. In the free-bacterial fraction, this ratio changed from 15.5:1 for the B-ns, to 1:1 for the B-s. Since iron was in replete conditions, our data suggest that this co-occurrence is more related to the vitamin supply.

The third most abundant species was from the phylum Bacteroidetes. This phylum has been recognized as specialist for the degradation of macromolecules, having a preference for growth attached to particles, surfaces or algal cells (Fernández-Gómez et al., 2013; Mann et al., 2013). Our data follow this pattern, since the attached fraction in B-s and B-ns cultures was enriched with member of this group. In the B-s condition, the Bacteroidetes accounted for 27%, mainly represented by Fluviicola sp., whereas in the B-ns culture, Fluviicola sp. represented 13.5% (Figure 5). This bacterial species has been previously reported during a L. polyedrum bloom, exhibiting its highest peak during the middle bloom stage, and a second peak at the end of the bloom, mainly clustered with other Flavobacteria species (Mayali et al., 2010, 2011).

Other alphaproteobacterial species were detected in the samples. Maricaulis sp. has been detected associated with toxic and non-toxic dinoflagellates in culture (Hold et al., 2001; Strömpl et al., 2003) but its relation to dinoflagellate ecophysiology is not known. Another species was Pelagibaca sp., and despite its enrichment in the B-ns amendment, its closest relative, Pelagibaca bermudensis HTCC2601 has only been detected with a free-living lifestyle (Slightom and Buchan, 2009), although some members of the Roseobacter clade, are known to have the potential to synthesize cobalamin, thiamine and iron siderophores (Newton et al., 2010). Erythrobacter sp. was an infrequent species but showed >1% in the B-s attached fraction. Erythrobacter sp., a marine aerobic anoxygenic phototroph like Dinoroseobacter shibae (Koblížek et al., 2003; Wagner-Döbler et al., 2010), is known for its free-living lifestyle that is scarcely detected in dinoflagellate cultures (Green et al., 2015). Although FISH counts showed that the phylum Bacteroidetes was numerically less abundant in all dinoflagellate growth phases than other groups, the Illumina data showed that their contribution during exponential phase accounted for 13.98% of the attached bacteria (FISH 0.9%) for B-ns, and 27.8% (FISH 1%) in B-s; and for free-bacteria 0.1% (FISH 3.6%) for B-ns, and 8% (FISH 1%) for B-s (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of taxonomic classification of bacterial groups at phylum and class levels from 16 rDNA-FISH hybridization and 16S rDNA (V3–V4) Illumina reads.

The community composition obtained using FISH counts differed from the 16S rDNA amplicon reads (Figure 6). This type of difference has been observed before (Dawson et al., 2012; Lenchi et al., 2013). There are different possible explanations for these differences: FISH probe hybridization efficiency or the relative amount of inactive cells that could not be visualized by FISH were probably not responsible for the difference because the FISH count were checked against the eubacterial probe EUB338 and DAPI staining showing that most prokaryotes were stained by FISH (Figures 4A,B). Another explanation for the difference might have been the low coverage of the probe for the represented groups in the culture, given that probe ALF968 covers approximately 81% of the class Alphaproteobacteria, probe GAM42a covers approximately 76% of the class Gammaproteobacteria, and CF319a covers approximately 38% of the phylum Bacteroidetes (Amann and Fuchs, 2008). Because we were working with probes previously used in research related to the bacterial diversity associated with dinoflagellates (Alavi et al., 2001; Alverca et al., 2002; Biegala et al., 2002; Garcés et al., 2007; Cruz-López and Maske, 2014) we did not confirm the selected probes targeted sequences in our Illumina data set before FISH experiments. One simple reason for the difference could be that the primers used to target the V3-V4 region (V3 338-533, V4 576-682; Escherichia coli 16S SSU rDNA numbering) and the FISH probes covered different regions or even the 23S rDNA subunit (Table 1) did not allow us to make a direct correlation between the two techniques. Dawson et al. (2012) and Lenchi et al. (2013), suggested different explanations for the difference, the underrepresentation of some phyla, PCR primer or gene copy number bias in the 16S rRNA sequencing, or the possibility of bacterial groups not being properly covered by the probe combination used, and the low relative abundance arguments that we would reject for reasons mentioned above.

Dissolved B12 Synthesis from the Microbial Community

Our results show that although the concentration of B12 in the B-s culture was higher than in the B-ns culture, this difference should be the result of the initial supplemented concentration from L1. The B-s culture medium contained initially 370 pmol L–1 of B12 that was reduced to 26 pmol L–1 during culture growth, close to twice the concentration in the exponential phase B-ns culture of 14.4 pmol L–1. The high consumption of B12 in the B-s culture might be due not only to L. polyedrum but also to the bacterial community. Neither of the culture concentrations was expected to be limiting the growth rate of L. polyedrum because these concentrations were as high as in very productive coastal waters. In the case of the B-ns culture the source of B12 was the microbial community maintaining the exponential growth phase of L. polyedrum while being supported by organic substrate provided by the phototroph host. The L. polyedrum biomass in B-ns and B-s cultures during vitamin sampling was similar. If we assume that the vitamin consumption is proportional to L. polyedrum biomass, neglecting B12 luxury uptake by L. polyedrum, consumption by bacteria or the production by bacteria in the B-s culture. From this we can roughly estimate that 370 –26 pmol L–1 of B12 was produced by the bacterial community during B-ns culture development to support the growth 8 × 106 L. polyedrum cells L–1 (Supplementary Figure S1), which amounts to 4 × 10–17 mol B12 cell–1. This high potential of B12 production while being supported by organics provided by the auxotrophic L. polyedrum suggests an easy capacity for the bacterial community to supply the oceanic auxotrophs phototrophs with B12 as long as no other controls limit the bacterial development. Our data suggest that B12 synthesis in the L. polyedrum/bacterial community respond to changes in B12 concentration, and that the supply may depend on the extent of B1 and B12 limitation, which in turn selects the bacterial community structure and it B1 and B12 synthesis capacity. The next step to study the contribution of all players within this type of system would be the use of metatranscriptomics combined with mass-spectrometry for the quantification of gene expression levels and its products, to estimate the contribution of eukaryotic DOC exudation and bacterial products.

Conclusion

In this work we have shown that L. polyedrum is a B1 and B12 auxotroph. Non-axenic cultures of L. polyedrum can acquire both vitamins from the associated bacterial community in sufficient quantity to sustain the maximum growth rate defined by culture conditions. The growth of the associated heterotrophic bacterial community was sustained by substrates provided by L. polyedrum because the culture medium was not amended with organic substrates.

Previous studies have shown B12 auxotrophy of dinoflagellates and diatoms species and the acquisition of B12 from a bacterial partner, however, is its known that, phytoplankton such as dinoflagellates not only require B12, but also B1, and they naturally interact with bacterial and archaeal communities, rather than with single bacterial species.

A small portion of the associated bacterial community was attached to the L. polyedrum cells; with or without vitamin addition to the culture medium the statistics of attachment, the proportion of L. polyedrum cells with bacteria attached or the number of bacteria attached to L. polyedrum cells did not change, but the abundance of freely suspended bacteria was significantly higher in B-ns culture. Using the same bacterial community inoculum, we showed that a characteristic bacterial community emerges even under contrasting vitamin amendments. We demonstrate that by association, the microbial community in the B-ns culture was able to synthesize and excrete sufficient B1 and B12 quantities to sustain the growth of its dinoflagellate host while being supported by organic substrates supplied by the host.

Author Contributions

All authors listed, have made substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for constructive comments and suggestions. Professor Michael Latz (UCSD-Scripps Institution of Oceanography) kindly provided us with the L. polyedrum HJ strain.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACyT) project CB-2008-01 106003 (to HM) and a Ph.D. fellowship (to RC-L).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00560

Growth of L. polyedrum and associated bacteria culture under B-s ( ) and B-ns (

) and B-ns ( ) conditions. (A)

L. polyedrum abundance. (B) Free-bacteria abundance. (C) Percent of L. polyedrum cells colonized by bacteria.

) conditions. (A)

L. polyedrum abundance. (B) Free-bacteria abundance. (C) Percent of L. polyedrum cells colonized by bacteria.

References

- Alavi M., Miller T., Erlandson K., Schneider R., Belas R. (2001). Bacterial community associated with Pfiesteria-like dinoflagellate cultures. Environ. Microbiol. 3 380–396. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alverca E., Biegala I. C., Kennaway G. M., Lewis J., Franca S. (2002). In situ identification and localization of bacteria associated with Gyrodinium instriatum (Gymnodiniales, Dinophyceae) by electron and confocal microscopy. Eur. J. Phycol. 37 523–530. 10.1017/S0967026202003955 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amann R., Fuchs B. M. (2008). Single-cell identification in microbial communities by improved fluorescence in situ hybridization techniques. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6 339–348. 10.1038/nrmicro1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amann R. I., Binder B. J., Olson R. J., Chisholm S. W., Devereux R., Stahl D. A. (1990). Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56 1919–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin S. A., Green D. H., Hart M. C., Küpper F. C., Sunda W. G., Carrano C. J. (2009). Photolysis of iron-siderophore chelates promotes bacterial-algal mutualism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 17071–17076. 10.1073/pnas.0905512106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr J., Auro R., Furlan M., Whiteson K. L., Erb M. L., Pogliano J., et al. (2013). Bacteriophage adhering to mucus provide a non-host-derived immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 10771–10776. 10.1073/pnas.1305923110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin M., Roy S., Daoust P., Dagenais-Bellefeuille S., Bertomeu T., Letourneau L., et al. (2012). Dinoflagellate tandem array gene transcripts are highly conserved and not polycistronic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 15793–15798. 10.1073/pnas.1206683109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand E. M., Saito M. A., Rose J. M., Riesselman C. R., Lohan M. C., Noble A. E., et al. (2007). Vitamin B12 and iron co-limitation of phytoplankton growth in the Ross Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 52 1079–1093. 10.4319/lo.2007.52.3.1079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biegala I. C., Kennaway G., Alverca E., Lennon J. F., Vaulot D., Simon N. (2002). Identification of bacteria associated with dinoflagellates (Dinophyceae) Alexandrium spp. using tyramide signal amplification-fluorescence in situ hybridization and confocal microscopy. J. Phycol. 38 404–411. 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2002.01045.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolch C. J. S., Subramanian T. A., Green D. H. (2011). The toxic dinoflagellate Gymnodinium catenatum (Dinophyceae) requires marine bacteria for growth. J. Phycol. 47 1009–1022. 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2011.01043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet S., Webb E. A., Panzeca C., Karl D., Capone D. G., Sañudo-Wilhelmy S. A. (2010). Vitamin B12 excretion by cultures of the marine cyanobacteria Crocosphaera and Synechococcus. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55 1959–1964. 10.4319/lo.2010.55.4.1959 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder J. M., Glibert P. M., Skelton H. M. (2008). Mixotrophy, a major mode of nutrition for harmful algal species in eutrophic waters. Harm. Alg. 8 77–93. 10.1016/j.hal.2008.08.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci A. F. (1970). “Part II. Vitamin B12 thiamine, biotin,” in The Ecology of the Phytoplankton Off La Jolla, ed. Strickland J. D. H. (Berkeley: University of California Press; ), 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Croft M. T., Lawrence A. D., Raux-Deery E., Warren M. J., Smith A. G. (2005). Algae acquire vitamin B12 through a symbiotic relationship with bacteria. Nature 438 90–93. 10.1038/nature04056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft M. T., Warren M. J., Smith A. G. (2006). Algae need their vitamins. Euk. Cell 5 1175–1183. 10.1128/EC.00097-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-López R., Maske H. (2014). A non-amplified FISH protocol to identify simultaneously different bacterial groups attached to eukaryotic phytoplankton. J. Appl. Phycol. 27 797–804. 10.1007/s10811-014-0379-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson K. S., Strapoć D., Huizinga B., Lidstrom U., Ashby M., Macalady J. L. (2012). Quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of microbial consortia from a biogenic gas field in Alaska’s Cook Inlet basin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 3599–3605. 10.1128/AEM.07122-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droop M. M. (2007). Vitamins, phytoplankton and bacteria: symbiosis or scavenging? J. Plankton Res. 29 107–113. 10.1093/plankt/fbm009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durham B. P., Sharma S., Luo H., Smith C. B., Amin S. A., Bender S. J., et al. (2015). Cryptic carbon and sulfur cycling between surface ocean plankton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 453–457. 10.1073/pnas.1413137112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26 2460–2461. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2013). UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10 996–998. 10.1038/nmeth.2604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C., Haas B. J., Clemente J. C., Quince C., Night R. (2011). UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27 2194–2200. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fandino L. B., Riemann L., Steward G. F., Long R. A., Azam F. (2001). Variations in the bacterial community structure during a dinoflagellate bloom analyzed by DGGE and 16S rDNA sequencing. Aquat. Microbiol. Ecol. 23 119–130. 10.3354/ame023119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Gómez B., Richter M., Schüler M., Pinhassi J., Acinas S. G., González J. M., et al. (2013). Ecology of marine Bacteroidetes: a comparative genomics approach. ISME J. 7 1026–1037. 10.1038/ismej.2012.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcés E., Vila M., Reñé A., Alonso-Sáez L., Angles S., Luglie A., et al. (2007). Natural bacterioplankton assemblage composition during blooms of Alexandrium spp. (Dinophyceae) in NW Mediterranean coastal waters. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 46 55–70. 10.3354/ame046055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gärdes A., Kaeppel E., Shehzas A., Seebah S., Teeling H., Yarza P., et al. (2010). Complete genome sequence of Marinobacter adhaerens type strain (HP15), a diatom-interacting marine microorganism. Stand. Genom. Sci. 3 97–107. 10.1073/pnas.0905512106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöckner F. O., Fuchs B. M., Amann R. (1999). Bacterioplankton compositions of lakes and oceans: a first comparison based on fluorescence in situ hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 3721–3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobler C. J., Norman C., Panzeca C., Taylor G. T., Sañudo-Wilhelmy S. A. (2007). Effect of B-vitamins (B1, B12) and inorganic nutrients on algal bloom dynamics in a coastal ecosystem. Aquat. Microbiol. Ecol. 49 181–194. 10.3354/ame01132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green D. H., Bowman J. P., Smith E. A., Gutierrez T., Bolch C. J. (2006). Marinobacter algicola sp. nov., isolated from laboratory cultures of paralytic shellfish toxin-producing dinoflagellates. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56 523–527. 10.1099/ijs.0.63447-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D. H., Echavarri-Bravo V., Brennan D., Hart M. C. (2015). Bacterial Diversity associated with the Coccolithophorid algae Emiliania huxleyi and Coccolithus pelagicus f. braarudii. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015:194540 10.1155/2015/194540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D. H., Llewellyn L. E., Negri A. P., Blackburn S. I., Bolch C. J. S. (2004). Phylogenetic and functional diversity of the cultivable bacterial community associated with the paralytic shellfish poisoning dinoflagellate Gymnodinium catenatum. FEMS. Microbiol. Ecol. 46 345–357. 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00298-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillard R. R. L. (1975). “Culture of phytoplankton for feeding marine invertebrates,” in Culture of Marine Invertebrate Animals, eds Smith W. L., Chanley M. H. (New York, NY: Plenum Press; ), 26–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa Y., Martin J. L., Le Gresley M., Burke T., Rooney-Varga J. N. (2007). Microbial community diversity in the phycosphere of natural populations of the toxic alga, Alexandrium fundyense. Environ. Microbiol. 9 3108–3121. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01421.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings J. W. (2007). The Gonyaulax clock at 50: translational control of circadian expression. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 72 141–144. 10.1101/sqb.2007.72.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton A. D., Shenoy D. M., Hart M. C., Mogg A., Green D. H. (2012). Metabolism of DMSP, DMS and DMSO by the cultivable bacterial community associated with the DMSP-producing dinoflagellate Scrippsiella trochoidea. Biogeochemistry 110 131–146. 10.1007/s10533-012-9702-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herlemann D. P., Labrenz M., Jürgens K., Bertilsson S., Waniek J. J., Andersson A. F. (2011). Transition in bacterial communities along the 2000 km salinity gradient of the Baltic Sea. ISME J. 5 1571–1579. 10.1038/ismej.2011.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hold G. L., Smith E. A., Rappé M. S., Maas E. W., Moore E. R. B., Stroempl C., et al. (2001). Characterization of bacterial communities associated with toxic and non-toxic dinoflagellates: Alexandrium spp. and Scrippsiella trochoidea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 37 161–173. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2001.tb00864.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H. J., Yoo Y. D., Park J. Y., Song J. Y., Kim S. T., Lee S. H., et al. (2005). Feeding by phototrophic red-tide dinoflagellates: five species newly revealed and six species previously known to be mixotrophic. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 40 133–150. 10.3354/ame040133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazamia E., Czesnick H., Nguyen T. T., Croft M. T., Sherwood E., Sasso S., et al. (2012). Mutualistic interactions between vitamin B (12)-dependent algae and heterotrophic bacteria exhibit regulation. Environ. Microbiol. 14 1466–1476. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02733.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblížek M., Béjà O., Bidigare R. R., Christensen S., Benitez-Nelson B., Vetriani C., et al. (2003). Isolation and characterization of Erythrobacter sp. strains from the upper ocean. Arch. Microbiol. 180 327–338. 10.1007/s00203-003-0596-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch F., Hattenrath-Lehmann T. K., Goleski J. A., Sañudo-Wilhelmy S., Fisher N. S., Gobler C. J. (2012). Vitamin B1 and B12 uptake and cycling by plankton communities in coastal ecosystems. Front. Microbiol. 3:363 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch F., Marcoval A., Panzeca C., Bruland K. W., Sañudo-Wilhelmy S. A., Gobler C. J. (2011). The effects of vitamin B12 on phytoplankton growth and community structure in the Gulf of Alaska. Limnol. Oceanogr. 3 1023–1034. 10.4319/lo.2011.56.3.1023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo R. C., Lin S. (2013). Ectobiotic and endobiotic bacteria associated with Eutreptiella sp. Isolated from Long Island sound. Protist 164 60–74. 10.1016/j.protis.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenchi N., Inceoǧlu O., Kebbouche-Gana S., Gana M. L., Llirós M., Servais P., et al. (2013). Diversity of microbial communites in production and injection waters of algerian oilfields revealed by 16S rRNA gene amplicon 454 pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE 8:e66588 10.1371/journal.pone.0066588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H., Moran M. A. (2014). Evolutionary ecology of the marine Roseobacter clade. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Biol. Rev. 78 573–587. 10.1128/MMBR.00020-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann A. J., Hahnke R. L., Huang S., Werner J., Xing P., Barbeyron T., et al. (2013). The genome of the alga-associated marine flavobacterium Formosa agariphila KMM 3901T reveals a broad potential for degradation of algal polysaccharides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 6813–6822. 10.1128/AEM.01937-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manz W., Amann R., Ludwing W., Vancanneyt M., Schleifer K.-H. (1996). Application of a suite of 16S rRNA-specific oligonucleotide probes designed to investigate bacteria of the phylum cytophaga-flavobacter-bacteroides in the natural environment. Microbiology 142 1097–1106. 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayali X., Franks P. J. S., Azam F. (2008). Cultivation and ecosystem role of marine RCA cluster bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 2595–2603. 10.1128/AEM.02191-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayali X., Franks P. J. S., Burton R. S. (2011). Temporal attachment dynamics by distinct bacterial taxa during a dinoflagellate bloom. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 63 111–122. 10.3354/ame01483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayali X., Palenik B., Burton R. S. (2010). Dynamics of marine bacterial and phytoplankton populations using multiplex liquid bead array technology. Environ. Microbiol. 12 975–989. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.02142.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa A., Evans A. N., Kulis D. M., Hackett J. D., Erdner D. L., Anderson D. M., et al. (2010). Transcriptome profiling of a toxic dinoflagellate reveals a gene-rich protist and a potential impact on gene expression due to bacterial presence. PLoS ONE 5:e9688 10.1371/journal.pone.0009688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R. J., Griffin L. E., Bowles K. M., Meile C., Gifford S., Gvens C. E., et al. (2010). Genome characteristics of a generalist marine bacterial lineage. ISME J. 4 784–798. 10.1038/ismej.2009.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okbamichael M., Sañudo-Wilhelmy S. A. (2004). A new method for the determination of vitamin B12 in seawater. Anal. Chim. Acta 517 33–38. 10.1016/j.aca.2004.05.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios L., Marín M. (2008). Enzymatic permeabilization of the thecate dinoflagellate Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyceae) yields detection of intracellularly associated bacteria via catalyzed reporter deposition-fluorescence in situ hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 2244–2247. 10.1128/AEM.01144-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A. R., Nobel T., Steele J. A., Schwalbach M. S., Hewson I., Fuhrman J. A. (2007). Virus and prokaryote enumeration from planktonic marine environments. Epifluorescence microscopy with SYBR Green I. Nat. Prot. 2 269–276. 10.1038/nprot.2007.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Manjarrez J. L., Helenes J., Gaxiola-Castro G., Orellana-Cepeda E. (2005). Dinoflagellate cysts and Bloom events at Todos Santos Bay, Baja California, México, 1999–2000. Cont. Shelf Res. 25 1375–1393. 10.1016/j.csr.2005.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sañudo-Wilhelmy S. A., Gobler C. J., Okbamichael M., Taylor G. T. (2006). Regulation of phytoplankton dynamics by vitamin B12. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33:L04604 10.1029/2005GL025046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sañudo-Wilhelmy S. A., Gómez-Consarnau L., Suffridge C., Webb E. A. (2014). The role of B vitamins in marine biogeochemistry. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 6 141–14.29. 10.1146/annurev-marine-120710-100912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S., Eliceiri K. W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9 671–675. 10.1038/nmeth.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slightom R. N., Buchan A. (2009). Surface colonization by marine Roseobacters: integrating genotype and phenotype. App. Environ. Microbiol. 75 6027–6037. 10.1128/AEM.01508-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strömpl C., Hold G. L., Lünsdorf H., Graham J., Gallacher S., Abraham W.-R., et al. (2003). Oceanicaulis alexandrii gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel stalked bacterium isolated from a culture of the dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamarense (Lebour) Balech. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53 1901–1906. 10.1099/ijs.0.02635-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y. Z., Koch F., Gobler C. J. (2010). Most harmful algal bloom species are vitamin B1 and B12 auxotrophs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 20756–20761. 10.1073/pnas.1009566107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner-Döbler I., Ballhausen B., Berger M., Brinkhoff T., Buchholz I., Bunk B., et al. (2010). The complete genome sequence of the algal symbiont Dinoroseobacter shibae: a hitchhiker’s guide to life in the sea. ISME J. 4 61–77. 10.1038/ismej.2009.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B., Bishop S., Stessman D., Wright D., Spalding M. H., Halverson L. J. (2013). Chlamydomonas reinhardtii thermal tolerance enhancement mediated by a mutualistic interaction with vitamin B12-producing bacteria. ISME J. 7 1544–1555. 10.1038/ismej.2013.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Kobert K., Flouri T., Stamatakis A. (2013). PEAR: a fast and accurate Illumina Paired-End read merger. Bioinformatics 30 614–620. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q., Aller R. C., Kaushik A. (2011). Analysis of vitamin B12 in seawater and marine sediment porewater using ELISA. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 9 515–523. 10.4319/lom.2011.9.515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Growth of L. polyedrum and associated bacteria culture under B-s ( ) and B-ns (

) and B-ns ( ) conditions. (A)

L. polyedrum abundance. (B) Free-bacteria abundance. (C) Percent of L. polyedrum cells colonized by bacteria.

) conditions. (A)

L. polyedrum abundance. (B) Free-bacteria abundance. (C) Percent of L. polyedrum cells colonized by bacteria.