Abstract

Adult T-cell leukaemia-lymphoma is a rare haematological malignancy, which can cause severe hypercalcaemia and metastatic calcification resulting in life-threatening arrhythmias.

Keywords: adult HTLV-related T-cell leukaemia-lymphoma, arrhythmias, hypercalcaemia

Case presentation

A 37-year-old Afro-Caribbean woman was admitted with a three-week history of lethargy, myalgia and intermittent chest pain. Her medical history consisted only of an uncomplicated pregnancy. On admission, she had acute kidney injury with severe hypercalcaemia (Ca2+ 4.74 mmol/L) and proteinuria (Table 1). Treatment with intravenous fluids and empirical antimicrobials to cover presumed sepsis were initiated. She continued to deteriorate and was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for respiratory support and renal replacement therapy. The differential diagnosis was wide, including vasculitis, autoimmune disease, sepsis and malignancy, and the relevant tests were requested.

Table 1.

Serial laboratory results.

| Result | Day of admission to hospital | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb (g/L) | 113 | 111 | 101 | 93 | 107 |

| WCC (×109) | 19.8 | 24.6 | 19.4 | 21.1 | 34.3 |

| Neutrophils (×109) | 17.6 | 21.9 | 16.9 | 19·0 | 31.6 |

| Platelets (×109) | 225 | 217 | 170 | 157 | 192 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 134 | 133 | 144 | 145 | 138 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 5.0 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 6.4 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 22.1 | 24.2 | – | 15.9 | – |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 301 | 322 | 249 | 203 | 188 |

| (mmol/L) | 22 | 21 | 30 | 31 | 15 |

| Cl− (mmol/L) | 97 | 102 | 101 | 105 | 100 |

| Corrected calcium (mmol/L) | 4.56 | 4.74 | 4.38 | 4.26 | 3.32 |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2·4 | 2.8 |

| Magnesium (mmol/L) | 1.03 | 1.45 | 0.97 | 1.03 | 2.34 |

| Bilirubin (µmol/L) | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 59 | 51 | 38 | 48 | 70 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 163 | 153 | 139 | 130 | 175 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 336 | 335 | 233 | 214 | 232 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 26 | 23 | 20 | 20 | 19 |

| Urine protein/ creatinine ratio (mg protein/ mmol creatinine) | 1491 | – | – | – | – |

WBC: white blood cell count; Hb: haemoglobin; ALT: alanine transaminase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase.

A peripheral blood film confirmed leukocytosis with a left shift but no abnormal cells. An autoimmune screen, respiratory virus panel as well as tests for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C antibodies were negative. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) level was appropriately suppressed (Table 1).

Four days after admission to the ICU, she developed recurrent episodes of both narrow- and broad-complex tachycardia. An urgent echocardiogram revealed poor global systolic function with no pericardial effusion or obvious valvular abnormality. The corrected serum calcium concentration was 3.3 mmol/L at this time. Treatment with DC cardioversion and antiarrhythmics temporised the situation, but the patient displayed marked sensitivity to both amiodarone and lignocaine (leading to bradycardia) and adrenaline (producing ventricular tachycardia). Before a pacing wire could be placed, she had a fatal brady-tachy arrhythmia with prolonged cardiac arrest from which resuscitation was unsuccessful. At the time of death, the underlying diagnosis was unknown. At postmortem examination, the most striking findings were:

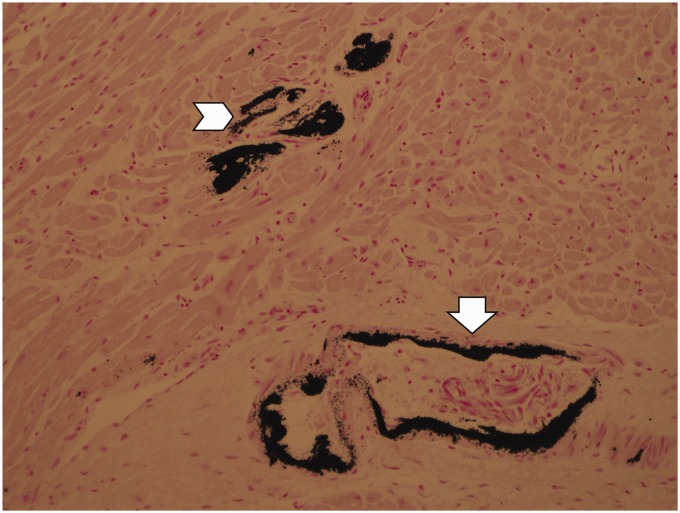

Intracellular calcium deposition in cardiac myocytes (Figure 1);

Widespread calcification in all medium- and small-sized arteries including intra-renal arteries with secondary micro-infarcts (Figure 1);

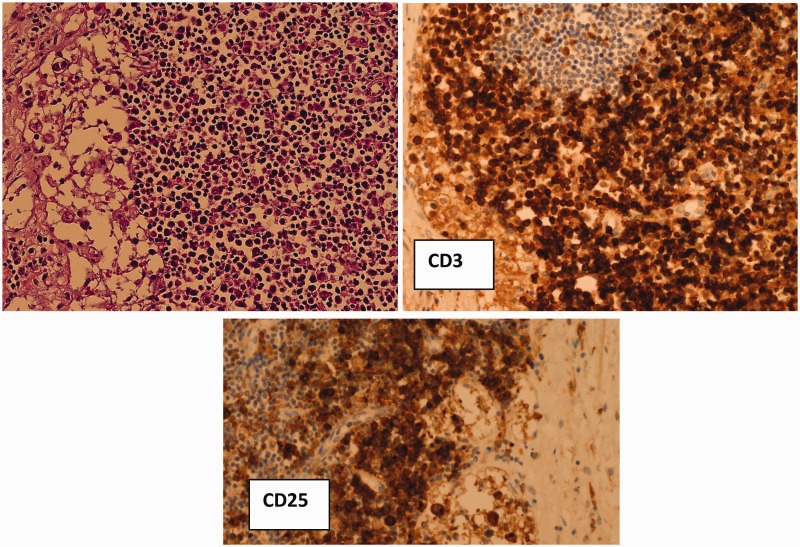

Infiltration of lymph nodes, bone marrow, lung and liver by large lymphoid blasts and features of histiocytic haemophagocytosis. The lymphoid blasts stained positively for CD3 and CD25 (Figure 2);

Figure 1.

Calcium deposition in coronary arteries (arrow) and cardiac myocytes (chevron) (von Kossa stain).

Figure 2.

Infiltration of lymph nodes by atypical CD3 and CD25 positive blasts (immunoperoxidase).

The parathyroid glands were histologically normal. Antibodies to human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV) type 1 were positive consistent with adult HTLV-related adult T-cell leukaemia-lymphoma (ATLL).

Discussion

Hypercalcaemia is a relatively common finding with diverse aetiologies. While primary hyperparathyroidism is the commonest worldwide cause, malignancy is likely to be the most frequent aetiology in hospitalised patients in the United Kingdom.1 Cancer may produce elevations in calcium through osteoclast activation, local oestolysis or generalised bone resorption.

Symptoms are often indolent and non-specific, including fatigue and anorexia with cardiac dysrhythmia a relatively infrequent manifestation. However, as illustrated by this case, severe arrhythmias can develop. At physiological levels, calcium has little effect upon the resting membrane potential of excitable tissues. However, in hypercalcaemia, phase two of the cardiac action potential may shorten, the QT interval may narrow and both cardiac conduction velocity and refractory period diminish. Hypercalcaemia > 3.4 mmol/L may produce second- or third-degree atrio-ventricular block.2 This combination of increased excitability and decreased refractoriness may facilitate re-entry phenomena and complex ventricular arrhythmias.3 As illustrated by our case, severe systemic hypercalaemica may also lead to intracellular and extracellular calcium deposition, including in cardiac myocytes which further increases the risk of arrhythmias. In addition, hypercalcaemia can impact upon cardiac contraction and myocardial relaxation, an observation similar to that seen with dialysis against both low- and high-calcium-containing fluids.4

In our patient, the underlying pathology and cause of severe arrhythmia were not identified until postmortem; extensive intra- and extracellular calcium deposition in her myocardium and other organs due to ATLL with widespread infiltration of lymph nodes, bone marrow, lungs and liver were seen. Interestingly, pre-mortem examination of her peripheral blood film did not reveal any malignant cells.

ATLL is a rare aggressive form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.5,6 It is classified into four major subtypes: smouldering, chronic, lymphomatous and leukaemic.4 Therapeutic options are limited although partial effectiveness has been seen with regimens such as rituximab/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisolone. Median survival is around 6–12 months.5

Chronic HTLV-1 infection is a known risk factor for ATLL. HTLV-1 was discovered in the 1980s, and the first retrovirus described in humans. It is ubiquitous across the world but endemic to South West Japan.7 As with all retroviruses, cellular infection is permanent. Transmission of the virus is similar to human immunodeficiency virus but early-life exposure (usually vertical transmission during lactation) seems to be of particular relevance to the development of ATLL.5

Hypercalcaemia is a prominent finding in 70–80% of patients with ATLL.8 The underlying mechanisms are related to direct or indirect osteoclast activation mainly due to PTH-related peptide and pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.7,9,10 In the setting of ATLL, systemic hypercalcaemia can lead to extensive calcification.10 Based on the clinical presentation, biochemical results and histological findings, we postulate that the combination of systemic hypercalcaemia and prodigious myocyte calcification together with pro-inflammatory processes produced refractory cardiovascular instability which explains our patient’s rapid demise.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

None declared

Ethical approval

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient’s next of kin prior to submission of this report.

Contributorship

SJS: collection of data, literature review, writing of 1st draft, writing of final draft. DW: data analysis, revision of manuscript, approval of final draft. UM: preparation of figures, analysis of data, revision of draft, approval of final draft. DG: analysis of data, literature review, revision of manuscript, approval of final draft. MSH: data interpretation, revision of manuscript, approval of final draft. MO: conception of case report, data analysis, revision of manuscript, approval of final draft, guarantor.

Guarantor

MO.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Nawaf Al-Subaie.

References

- 1.Minisola S, Pepe J, Piemonte S, Cipriani C. The diagnosis and management of hypercalcaemia. BMJ 2015; 350: h2723–h2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenqvist M, Nordenstrom J, Andersson M, Edhag OK. Cardiac conduction in patients with hypercalcaemia due to primary hyperparathyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1992; 37: 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vella A, Gerber TC, Hayes DL, Reeder GS. Digoxin, hypercalcaemia, and cardiac conduction. Postgrad Med J 1999; 75: 554–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nappi SE, Saha HH, Virtanen VK, Mustonen JT, Pasternack AI. Hemodialysis with high-calcium dialysate impairs cardiac relaxation. Kidney Int 1999; 55: 1091–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukasaki K. Adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma. Hematology 2012; 17(Suppl 1): S32–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehieux R, Gessain A. Adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma and HTLV-1. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2007; 2: 257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gotuzzo E, Cabrera J, Deza L, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in Peru with human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1-associated tropical spastic paraparesis. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39: 939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alves C, Dourado L. Endocrine and metabolic disorders in HTLV-1 infected patients. Braz J Infect Dis 2010; 14: 613–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nadella MV, Shu ST, Dirksen WP, et al. Expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein during immortalization of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by HTLV-1: implications for transformation. Retrovirology 2008; 5: 46–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumamoto H, Ichinohasama R, Sawai T, et al. Multiple organ failure associated with extensive metastatic calcification in a patient with an intermediate state of human T lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) infection: report of an autopsy case. Pathol Int 1998; 48: 313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]