Abstract

Background

The optimal timing of initiating renal replacement therapy (RRT) in critical illness complicated by acute kidney injury (AKI) is not clearly established. Trials completed on this topic have been marked by contradictory findings as well as quality and heterogeneity issues. Our goal was to perform a synthesis of the evidence regarding the impact of “early” versus “late” RRT in critically ill patients with AKI, focusing on the highest-quality research on this topic.

Methods

A literature search using the PubMed and Embase databases was completed to identify studies involving critically ill adult patients with AKI who received hemodialysis according to “early” versus “late”/“standard” criteria. The highest-quality studies were selected for meta-analysis. The primary outcome of interest was mortality at 1 month (composite of 28- and 30-day mortality). Secondary outcomes evaluated included intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital length of stay (LOS).

Results

Thirty-six studies (seven randomized controlled trials, ten prospective cohorts, and nineteen retrospective cohorts) were identified for detailed evaluation. Nine studies involving 1042 patients were considered to be of high quality and were included for quantitative analysis. No survival advantage was found with “early” RRT among high-quality studies with an OR of 0.665 (95 % CI 0.384–1.153, p = 0.146). Subgroup analysis by reason for ICU admission (surgical/medical) or definition of “early” (time/biochemical) showed no evidence of survival advantage. No significant differences were observed in ICU or hospital LOS among high-quality studies.

Conclusions

Our conclusion based on this evidence synthesis is that “early” initiation of RRT in critical illness complicated by AKI does not improve patient survival or confer reductions in ICU or hospital LOS.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1291-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, Intensive care units (ICUs), Acute kidney injury (AKI), Renal replacement therapy (RRT), Early, Late

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a medical complication associated with significant morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients [1–3]. AKI is common in critical illness, and severe AKI is associated with up to 60 % hospital mortality [4]. Renal replacement therapy (RRT) within the intensive care unit (ICU) is conducted as either intermittent hemodialysis or continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT). Traditional indications for RRT require the development of overt clinical manifestations of renal insufficiency, such as acidosis, electrolyte disturbances (most notably hyperkalemia), uremic complications (encephalopathy or pericarditis), and volume overload unresponsive to aggressive medical management. In spite of research and increasing clinical experience with dialysis, the optimal time to initiate RRT in the course of critical illness complicated by AKI is unclear.

The notion of “early” RRT is to initiate dialysis therapy before nitrogenous and other metabolic products accumulate to the degree where they become relatively resistant to therapy [5, 6]. Despite the intuitive rationale for “early” RRT, there is limited evidence to guide clinicians on the optimal time to initiate RRT in critical illness. Neither standard clinical parameters nor research into novel clinical biomarkers has emerged to clearly define an ideal time or clinical picture where the initiation of RRT optimizes patient outcomes. Earlier initiation of RRT must be balanced with potential patient harm associated with RRTs. Protocolled use of hemofiltration for 96 h in patients with septic shock admitted to an ICU regardless of their renal function suggests that “early” RRT can be associated with negative patient outcomes [7]. As a result, research into “early” RRT includes multiple definitions of early that reflect a potpourri of time factors, biochemical markers, and clinical parameters in an attempt to balance the risks of initiating RRT with the benefits expected from supporting renal function during critical illness.

The authors of two earlier meta-analyses pooled available data on this topic to suggest that “early” RRT improves survival in critical illness. Seabra et al. [8] identified 23 studies (5 randomized controlled trials [RCTs]/quasi-RCTs, 1 prospective study, and 17 retrospective cohort studies) and concluded that “early” initiation of RRT was associated with 28 % mortality risk reduction (relative risk [RR] 0.72, 95 % CI 0.64–0.82, p < 0.001). Karvellas et al. [9] identified 15 studies (2 RCTs, 4 prospective studies, and 9 retrospective cohort studies) and reached similar conclusions, reporting a significant improvement in 28-day mortality with “early” RRT (OR 0.45, 95 % CI 0.28–0.72, p < 0.001). However, the overall findings were not congruent with the subgroup analysis of randomized trials (RR 0.64, 95 % CI 0.4–1.05, p = 0.08), where there was a signal that “early” RRT was not associated with a significant survival advantage. This has diminished clinical confidence in the conclusions reached by the earlier meta-analyses, and consequently “early” RRT in critical illness remains a controversial therapeutic intervention.

Since 2012, additional studies have been published that do not support the conclusions of the previous meta-analyses, and this has further diminished the confidence in the previous conclusions that suggested a survival benefit in critical illness associated with “early” RRT. We conducted a systematic review and evidence synthesis to investigate whether “early” versus “late” initiation of RRT in critically ill patients with AKI improves patient survival and selected secondary outcomes for potential signals to suggest that “early” RRT may reduce patient morbidity or enhance illness recovery. Our goal was to identify the highest-quality studies on this topic and use a pooled meta-analysis of these studies to inform our conclusions.

Methods

Search strategy

This study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [10] (see Additional file 1: Figure S1 for PRISMA checklist). Our null hypothesis was that “early” initiation of RRT does not improve patient survival in critical care patients with AKI. This systematic review was not registered, and a protocol does not exist. The PubMed and Embase databases were searched to identify published articles following four broad themes: AKI, RRT, time of initiation, and critical illness (see Additional file 2: Table S1 for search terms). SK is a National Institutes of Health (NIH) physician and requested the NIH librarian to provide oversight for the search strategy. Our search was limited to English-language-only, full-text primary research publications (including abstracts with full text availability) reporting findings of clinical trials and observational studies (cohort and case-control design) published between January 1985 and November 2015. Studies before 1985 were not actively sought, owing to a low likelihood of relevance to modern RRTs and critical care practices.

Study selection

References were screened and excluded if they were small case reports or observational studies (fewer than 10 subjects), were not focused on critically ill adult patients, did not report mortality data, involved basic science data, or did not clearly distinguish between “early” and “late” groups. This task was divided among the authors. A second evaluation led by the senior author (RLCK) was conducted to evaluate study quality. Studies were designated as being of “high quality” or “low quality.” Studies were assigned a “low-quality” rating if there was no illness severity assessment between cohorts or at the time of randomization (n = 8), significant differences (p < 0.05) between cohort groups (n = 7) at baseline, incomplete basic demographic data at baseline (n = 6) to exclude baseline differences, or a Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment (NOQA) Scale [11] for cohort studies rating less than 7 (n = 6). The senior author (RLCK) was the arbiter in cases of disagreement. Only high-quality studies were included in quantitative meta-analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was mortality at 1 month (pooling outcomes for mortality at 28 or 30 days, depending on what was reported by the primary authors). In addition to mortality, we analyzed selected secondary outcomes, including ICU length of stay (LOS) and hospital LOS. Secondary outcomes were not consistently reported for all studies, and only studies with applicable data were included in our pooled analysis. Weighted means were calculated as a product of the number of patients and mean duration to reach a total and represented as a total of patient-days per study. These values were summed and divided by the total number of patients from all included studies to reach weighted mean duration of LOS for both hospital and ICU LOS metrics. A similar process was used to derive the mean weighted illness severity scores. Other potentially relevant secondary outcomes, including mechanical ventilation requirements, vasopressor requirements, and renal recovery rates, were considered, but these variables were inconsistently reported and commonalities could not be reached among the heterogeneous parameters that were available.

Definition of “early” versus “late”

Early was defined on the basis of criteria used by the original authors in their respective studies. We accepted a broad definition of early based on biochemical markers according to RIFLE classifications (risk, injury, failure, loss of function, and end-stage kidney disease), Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) stages, or time-based cutoffs (e.g., within a defined time from ICU admission or development of a biochemical “start time”). Accepting a broad definition of early was intended to optimize the potential for identifying an effect associated with “early” RRT. A limitation of this approach is that “early” according to one study investigator might be considered “late” by another study investigator. “Late” RRT criteria involved either usual practice or expectant care (i.e., no RRT initiated). “Usual practice” generally involved implementing RRT following the development of classic RRT indications unresponsive to medical management.

Statistical analysis

The quality of cohort trials was assessed using the NOQA Scale (range from 0 to 9, with 9 indicating the highest quality) [11]. The NOQA Scale for cohort studies assesses the domains of population selection, comparability of cohorts, and outcome assessment. A meta-analysis was conducted using the high-quality studies to calculate the pooled OR for mortality at 1 month. A random effects model was used because of the significant heterogeneity between studies on this topic. A random effects model is indicated when study populations differ in ways that could impact the results. Heterogeneity was assessed on the basis of the Q value and I2 and τ2 statistics. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3.3.070 software (www.meta-analysis.com; Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA).

Results

The systematic literature search yielded 2405 references that were subsequently refined to 36 studies eligible for inclusion in this meta-analysis (see Additional file 3: Figure S2 for article selection breakdown). These references included 7 RCTs [7, 12–17], 10 prospective cohort studies [18–27], and 19 retrospective cohort studies [28–46]. Only nine studies met our criteria for high quality [7, 12, 14–17, 21, 35, 40]. A summary of the fundamental characteristics of all evaluated studies is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Trial Summary Table by Study Type (n=36)

| Author, Year | Study Design | Country | Duration | Exclusion | Patient Population | Patients (n) | Age (mean) yrs | Illness Severity Score | Early RRT Criteria | Late RRT Criteria | Study Quality | Primary Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Early RRT | Late RRT | ||||||||||||

| Randomized Trials | ||||||||||||||

| Bouman, 2002 [12] | RCT, two-center study | Netherlands | May 1998 - Mar 2000 | Pre-existing renal disease | Multisystem | 106 | 70 | 36 | EHV: 68; ELV: 70; LLV: 67 | EHV: SOFA 10.3 - APACHE2=23.5, ELV: SOFA 10.1 - APACHE2=21.7; LLV: SOFA 10.6 - APACHE2=23.6 | TIME: Early < 12 h (200ml); Early Low Vol < 12 h (100-150ml) | TIME: Late > 12h | HIGH | 28 d mortality: EHV: 9/35(26%) died, ELV: 11/35(31%) died, LLV: 9/36(25%) died; p=0.8 |

| Durmaz, 2003 [13] | RCT | Turkey | Sept 1999 - Aug 2001 | Age<18, chronic dialysis | Post Cardiac Surgery | 44 | 21 | 23 | Early 58; Late 54 | NR | BIOCHEM: Cr rise >10% from pre-op level within 48hrs of surgery | Cr rise >50% from pre-op level; or Urine output <400ml/24hrs with coexistent K+/H+ unresponsive to med mgmt | LOW | Hospital mortality: Early 1/21 (4.8%) died, Late 7/23 (30.4%) died p=0.048; Favors Early |

| Sugahara, 2004 [14] | RCT | Japan | Jan 1995 - Dec 1997 | Pregnancy, Bili > 5mg/dL, Mental disorder, Cancer, Early recovery of urine output >30ml/kg/hr prior to RRT | Post Cardiac Surgery | 28 | 14 | 14 | Early: 65; Late: 64 | Early: APACHE2=19; Late: APACHE2=18 | BIOCHEM: UOP <30ml/hr × 3hrs OR UOP <750ml/day; Mean time to RRT start 18d±0.9 post op | UOP<20ml/hr × 2hrs+ OR UOP <500ml/day; Mean time to RRT start 1.7d±0.8 post op | HIGH | 14 d mortality: Early 2/14 died (14%), Late 12/14 died (86%); p<0.01 Favors Early |

| Payen, 2009 [7] | RCT, multicenter | France | Jan 1997 - Jan 2000 | Age<18, chronic dialysis, pregnant, moribund state, prior immunosuppressive therapy | Multisystem | 76 | 37 | 39 | Early 58 Late 59 | Early: SOFA 11.6- SAPS2 54.3; Late: SOFA 10.4- SAPS2 52.4 | TIME: Protocolized RRT × 96hrs w/ diagnosis of ‘sepsis’. Mean time to initiation of RRT not specified | Control = No RRT unless metabolic renal failure & classic indications for RRT present | HIGH | Early 20/37 (54%) died, Late 17/37 (44%) died; p = 0.49 |

| Jamale, 2013 [15] | RCT, single center | India | April 2010 - July 2012 | Required urgent dialysis at time of randomization | Multisystem | 208 | 102 | 106 | Early 43 Late 42 | Early: SOFA 7.3; Late: SOFA 8.2 | BIOCHEM: Cr > 618μmol/L | Classic indications for RRT, Symptomatic uremia unresponsive to med mgmt | HIGH | Mortality: Early 21/102 (20.5%) died, Late 13/106 (12%); p=0.2 |

| Combes, 2015 [16] | RCT, multicenter | USA | 2009-2012 | <18, Pregnant, Chronic RRT, Weight >120kg, SAPS II>90 (i.e. moribund) | Post Cardiac Surgery | 224 | 112 | 112 | Early 61 Late 58 | Early: SOFA 11.5- SAPS2=54; Late: SOFA 12.0- SAPS2=55.1 | TIME: RRT initiated <24hrs and continued for min of 48hrs; Mean time to randomization 12hrs | Classic indications for RRT, Lifethreatening metabolic derangements unresponsive to med mgmt | HIGH | Mortality: Early 40/112 (36%) died, Late 40/112 (36%) died; p = 1.0 |

| Wald, 2015 [17] | RCT, multicenter | Canada | May 2012 - Nov 2013 | Intoxication requiring RRT, Limited resuscitation directives, RRT within the previous 2 months, RPGN, Obstructive uropathy, > 48hrs to doubling time of Cr | Multisystem | 100 | 48 | 52 | Early 62 Late 64 | Early: SOFA 13.3 Late: SOFA 12.8 | TIME: Time from randomization < 12h; Mean time to RRT = 9.7hrs | Intensivist judgement regarding hyperkalemia, volume overload, acidemia refractory to medical therapy, Uremic symptoms Mean time to RRT=32hrs | HIGH | Mortality: Early 16/48 (33%) died, Late 19/52 died; p = 0.74 |

| RCT Totals | 786 | 404 | 382 | Pooled mortality: Early 120/404 (29.7%), Late 117/382 (30.6%); n=7 | ||||||||||

| Prospective Trials | ||||||||||||||

| Liu, 2006 [18] | Prospective Observational Multicentre | Multi countries | Feb 1999 - Aug 2001 | GFR<30ml/min/1.73m2 | Multisystem | 243 | 122 | 121 | Early 54 Late 58 | NR | Azotemia defined by BUN<76mg/dL | Azotemia defined by BUN>76mg/dL | LOW NOQA=6 | 28 d mortality: Early 43/122(35%) died vs Late 50/121(41%) P=0.09 Favors Early |

| Iyem, 2009 [19] | Prospective Observational cohort | Turkey | May 2004 - April 2007 | Preexisting renal disease and pre operative high levels of urea and creatinine | Post cardiac surgery | 185 | 95 | 90 | Early: 64; Late: 62 | NR | TIME: Evidence of 50% increase in BUN, low urine output (<0.5mL/kg/h) triggering RRT started < 48hrs | TIME > 48hrs to start of RRT for similar markers of renal failure managed medically for minimum 48hrs | LOW NOQA=7 | In hosp mortality: Early 5/95(5%) died, Late 6/90(7%) died; NS |

| Bagshaw, 2009 [20] | Prospective Observational Multicentre (BEST Kidney) | 23 countries | Sept 2000 - Dec 2001 | Pre existing chronic RRT, drug toxicity, age <12 | Multisystem | 1227 | 959 | 268 | Early: 60, Delayed: 63, Late: 64; p=0.003 | Early: SOFA 10.9- SAPS2=53.5 Delayed: SOFA 11.1- SAPS2=46 Late: SOFA 10.7- SAPS2=43.1; p=0.04 | TIME: Early RRT started for azotemia (Urea>30mmol/L or low urine output × 12h) <2d (n=785), Delayed RRT started 2-5d (n=174) from ICU admission | RRT started >5d from ICU admission | LOW NOQA=7 | Hosp mortality: Early 462/785(59%) died, Delayed 108/174(62%) died, Late 195/268(72%) died; P<0.0011 Favors Early |

| Shiao, 2009 [21] | Prospective Observational Multicentre | Taiwan | Jan 2002 - Dec2005 | Prior dialysis, without surgery, or surgery did not involve abdominal cavity. History of renal trasplant | Major abdominal surgery | 98 | 51 | 47 | Early: 65; Late: 68 | Early: SOFA 8.3- APACHE2=18.2; Late: SOFA 8.5- APACHE2=18.8 | BIOCHEM: RIFLE criteria: RISK or pre-RISK criteria (Mean Time to RRT from ICU Admit = 7.3d) | RIFLE criteria: INJURY or FAILURE criteria (Mean Time to RRT from ICU Admit=8.4d) | HIGH NOQA=7 | Hosp mortality: Early 22/51(43%), Late35/47(75%); p=0.0028 Favors Early |

| Sabater, 2009 [22] | Prospective Observational | Spain | 2 years | NR | Multisystem | 148 | 44 | 104 | All patients mean = 60; NR | Early: APACHE2=26; Late: APACHE2=24 | BIOCHEM: RRT initiated for RIFLE: RISK & INJURY; (Mean RRT start 2.2d post ICU admit) | RRT initiated for RIFLE: FAILURE; (Mean RRT start 6.4d post ICU admit) | LOW NOQA=7 | Mortality: Early 21/44 died, Late 68/104 died. P=0.047 Favors Early |

| Elseviers, 2010 [23] | Prospective Observational Multicentre | Belgium | 2001-2005 | Pre existing renal disease (Cr<1.5mg/dl), reduced kidney size on ultrasound | Multisystem | 1303 | 653 | 650 | Early 64; Late 67 | Early: SOFA 9.9- APACHE2=25.2; Late: SOFA 8.5- APACHE2=5.2, p=0.001 | BIOCHEM: Unspecified SHARF scoring criteria w/serum Cr > 2mg/dL | Conservative approach = No RRT | LOW NOQA=5 | Mortality: Early 379/653 (58%) died, Late 280/650 (43%) died; p<0.001 Favors Late |

| Vaara, 2012 [24] | Prospective Observational Multicentre (FINNAKI Study) | Finland | Sep 2011 - Feb 2012 | NR | Sepsis, Cardiogenic Shock | 261 | NR | NR | NR | Survivors: SAPS2=47; Non-survivors: SAPS2=66 | TIME: Time<24hrs from ICU admit | Time> 24hrs from ICU admit | LOW NOQA=5 | OR for late 2.69 (1.07-6.73, p=0.035). Favors Early |

| Perez, 2012 [25] | Prospective Observational | Spain | NR | Sepsis | 244 | 135 | 109 | Early 62; Late 62 | Early: SOFA 12; Late: SOFA 11 | TIME: Time from ICU admission to RRT < 48h | TIME >48hrs | LOW NOQA=5 | 90 d mortality: Early 71/135(53%) died, Late 78/109(72%) died; p=0.003. Favors Early | |

| Lim, 2014 [27] | Single Centre Prospective Cohort | Singapore | Dec 2010 - April 2013 | Chronic dialysis patients, Dialysis initiated prior to ICU admission | Medical & Surgical patients | 140 | 84 | 56 | Early 60; Late 64 | Early: SOFA 7; Late: SOFA 11; p=0.001 | BIOCHEM: AKIN stage 1 or 2 AND compelling indication or AKIN stage 3 (Cr≥354μmol/l or Cr>300% baseline w/urine <0.3cc/kg/h for 24h or anuria >12h) | Traditional indications: K>6mmol/L, Urea ≥30mmol/L, pH<7.25, Bicarb <10mmol/L, Pulm edema, Uremic encephalopathy/pericarditis | LOW NOQA=6 | Hosp mortality: Early 36/84(43%) died, Late 37/56(66%) died; p=0.007 Favors Early |

| Jun, 2014 [26] | Nested Observational, Multi-Centre Study ‘RENAL’ Study Group | NZ, Australia | Dec 2005 - Nov 2008 | Age<18, Prior RRTduring admission, Prior RRT for CKD | Sepsis | 439 | 219 | 220 | Early 65; Late 64 | Early: SOFA: 2.0- APACHE3=107, Late: SOFA 2.1- APACHE3=100, P<0.001 | TIME: AKI diagnosis to randomization < 17.6 hrs | Time from AKI diagnosis to randomization >17.6hrs | LOW NOQA=6 | 28 d mortality: Early 82/219(37%) died; Late 84/220(38%) died (p=0.923) NS |

| PROSPECTIVE TOTALS | 4288 | 2362 | 1665 | Pooled mortality: Early 1229/2362 (52%), Late 833/1665 (50%); n=10 | ||||||||||

| Retrospective Trials | ||||||||||||||

| Gettings, 1999 [28] | Retrospective cohort | USA | 1989 - 1997 | CRRT duration <48hrs, Pediatric patients, Incomplete records | Trauma | 100 | 41 | 59 | Early 40; Late 48 | Early ISS = 33.0; Late ISS = 37.2 | BIOCHEM: BUN < 60mg/dL AND Oliguria, Vol overload, Electrolytes, Uremia; Mean RRT start post admission day 10; p<0.0001 | BUN > 60 mg/dL AND Oliguria, Vol overload, Electrolytes, Uremia; Mean RRT start post admission day 19 | LOW NOQA=5 | Hosp mortality: Early 25/41(61%) died, Late 47/59(80%) died; p=0.041 Favors Early |

| Elahi, 2004 [29] | Retrospective cohort | UK | Jan 2002 - Jan 2003 | Preexisting renal disease | Post cardiac surgery | 64 | 36 | 28 | Early 69; Late 68 | NR | BIOCHEM: Low urine output = less than 100 ml within 8h after surgery;Mean RRT start 0.78 days | Traditional indications: Urea ≥30mmol/L, Cr Elahi, 2004 [29] ≥250mmol/L, K > 6.0mEq/L; Mean RRT start 2.5 days | LOW NOQA=6 | 28 d mortality: Early-8/36 died (22%), Late-12/28 (43%); p<0.05 Favors Early |

| Demirkilic, 2004 [30] | Retrospective cohort | Turkey | Mar 1992 - Sep 2001 | NR | Post Cardiac Surgery | 61 | 34 | 27 | NR p=0.3 | NR | BIOCHEM: Low urine output = less than 100ml within 8hrs post op; Mean RRT start 0.88 days | Cr≥5mg/dL, or K>5.5 mEq/L w/med mgmt; Mar 92-Jun 96; Mean RRT start 2.56 days | LOW NOQA=6 | Hosp mortality: Early 8/34(23%), Late 15/27(56%); P=0.016 Favors Early |

| Wu, 2007 [32] | Retrospective cohort | Taiwan | July 2002- Jan2005 | Hepatorenal syndrome from cirrhosis, liver trasplant, cardiopolmunary resuccitation | Acute liver failure | 80 | 54 | 26 | Early 55; Late 63; p=0.03 | Early: SOFA 12.4- APACHE2=18.2; Late: SOFA 13.2- APACHE2=20.5 | BIOCHEM: BUN < 80 mg/dL AND traditional indications present | Traditional indications present with BUN > 80mg/dL | LOW NOQA=6 | 30 d mortality: Early 34/54(63%) died vs Late 22/26(85%) died; P=0.04 Favors Early |

| Andrade, 2007 [31] | Retrospective cohort | Brazil | 2002-2005 | Patients who did not have both AKI and respiratory failure believed secondary to leptospirosis | Leptospirosis | 33 | 18 | 15 | Early 42; Late 44 | Early: APACHE2=24.5; Late: APACHE2=26 | TIME: Mean time to RRT = 265 min | Mean time to RRT = 1638 min | LOW NOQA=5 | Hosp mortality: Early 3/18(17%) died, Late 10/15(67%) died; P=0.01 Favors Early |

| Manche, 2008 [33] | Retrospective cohort | Malta | 1995-2006 | NR | Post Cardiac Surgery | 71 | 56 | 15 | Early 66; Late 63 | NR | BIOCHEM: Urine output<0.5ml/kg/hr unresponsive to med mgmt; Mean RRT start 8.6hrs post-op | Oliguria (output < 0.5ml/Kg/hr) refractory to med mgmt; Mean RRT start 41.2hrs post-op | LOW NOQA=6 | Mortality: Early 14/56(25%) died, Late 13/15(87%) died; P=0.0000125 Favors Early |

| Lundy, 2009 [34] | Retrospective cohort | US | Nov 2005 - Aug 2007 | Preexisting renal disease, burn size of less than 40% Non-thermal injury, lithium toxicity | Severe Burned patients | 57 | 29 | 28 | Early 27; Late 38 P=0.06 | Early: SOFA 13- APACHE2=35; Late: SOFA 13- APACHE2=36 | BIOCHEM: AKIN stage 2(+shock)/3; Mean time from admit to RRT = 17 days | Mean time from admit to AKIN stage 2(+shock)/3 but not dialyzed = 23 days | LOW NOQA=6 | 28 d mortality: Early 9/29(31%) died, Late 24/28(85%) died; P<0.002; Favors Early |

| Carl, 2010 [35] | Retrospective cohort | US | 2000-2004 | Baseline eGF0R <30ml/min, Age <18 & prisoners | Sepsis | 147 | 85 | 62 | Early 52; Late 56 | Early: APACHE2=24.8; Late: APACHE2=24.7 | BIOCHEM: BUN <100mg/dL + AKIN stage >2; Mean ICU stay prior to RRT =6.3days | BUN > 100mg/dL + AKIN stage >2; Mean ICU stay prior to RRT=12.3days | HIGH NOQA=7 | 28 d mortality: Early 44/85(52%) died, Late 42/62(68%); P<0.05 Favors Early |

| Chou, 2011 [37] | Retrospective cohort ‘NSARF’ database | Taiwan | Jan 2002 - Oct 2009 | Age< 18, ICU stay <2days, RRT < 2days | Sepsis + AKI | 370 | 192 | 178 | Early 64; Late 66 | Early: SOFA 10.8- APACHE2=12.3; Late: SOFA 11.6- APACHE2=14.0 | BIOCHEM: RIFLE criteria: RISK or pre-RISK criteria | RIFLE criteria: INJURY or FAILURE criteria | LOW NOQA=6 | Hosp mortality: Early 135/192(71%) died, Late 124/178 (70%) died (P=0.98) |

| Vats, 2011 [38] | Retrospective cohort | USA | Jan1999 - Feb 2006 | Renal transplant, Pre-morbid ESRD on dialysis, RRT<24h, insufficient data | Multisystem | 230 | NR | NR | All patients mean = 66 NR | NR | TIME: Time from AKI to RRT < 6 days | Time from AKI to RRT≥6d | LOW NOQA=5 | OR for Late Mortality (>6d) 11.66 (1.26-107.9) P=0.0305, Favors Early |

| Ji, 2011 [36] | Retrospective cohort | China | Ap 2004 - Mar 2009 | Patients readmitted post discharge, Discharged against medical advice, Death <24hrs | Post cardiac surgery | 58 | 34 | 24 | Early 64; Late 62 | Early: APACHE3=69.3; Late: APACHE3=88.2 p<0.001 | TIME: Time from urine output <0.5ml/kg/h to RRT<12h; Mean oliguria to start of RRT 8.4hrs | Urine output <0.5ml/kg/h & Time to RRT>12h post oliguria; Mean oliguria to start of RRT 21.5hrs | LOW NOQA=6 | Hosp mortality: Early 3/34 (9%) died, Late 9/24 (37%); p=0.02 Favors Early |

| Shiao, 2012 [41] | Retrospective cohort ‘NSARF’ database | Taiwan | Jan 2002 - Apr 2009 | Dialysis before surgery, ESRD | Surgical | 648 | 436 | 212 | Early 62; Late 66; P=0.009 | Early: SOFA 11.4- APACHE2=12.7; Late: SOFA 11.3- APACHE2=12.8 | TIME: Time to development of tradtional RRT indications < 3d; Mean time to start of RRT 1.4days | Traditional RRT indications AND start of RRT > 3 days; Mean time to start of RRT 18days | LOW NOQA=6 | Hosp mortality: Early 236/436 (54%) died, Late 143/212 (67%) died; P=0.001 Favors Early |

| Chon, 2012 [40] | Retrospective cohort | South Korea | Apr 2009 - Oct 2010 | Liver cirrhosis, Pre existing chronic | Sepsis | 55 | 36 | 19 | Early 63; Late 62 | Early: SOFA 13.5- APACHE2= 28.7; Late: SOFA 12- APACHE2=28.3 | TIME: Time to RIFLE ‘Injury’/‘Failure’ < 24hrs; Mean time to RRT=12.5hrs | Time to RIFLE ‘Injury’/‘Failure’ > 24hrs; Mean time to RRT= 42.2hrs | HIGH NOQA=7 | 28 d mortality: Early 7/36(38%), Late 9/19(47%); P=0.03 Favors Early |

| Boussekey, 2012 [39] | Retrospective cohort | France | Jan 2008 - Dec 2010 | Early trasfer to another unit | Multisystem | 110 | 67 | 43 | Early 62; Late 66 | Early: SOFA: 11.1- SAPS2=70; Late: SOFA 8.8- SAPS2=57; p=0.002 | TIME: Time from RIFLE- ‘Injury’ to RRT < 16hrs; Mean time to RRT=6hrs | Time from RIFLE-‘Injury’ to RRT > 16hrs; Mean time to RRT=64hrs | LOW NOQA=7 | 28 d mortality: Early-28/67 (41%), Late- 28/43 (65%); P = 0.0425 Favors Early |

| Suzuki, 2013 [43] | Retrospective cohort | Japan | Jan 2009 - Feb 2013 | <18, RRT for ESRD | Sepsis, Cardiogenic Shock | 189 | 52 | 137 | All patients mean = 72 NR | All patients SAPS II Mean= 57 | BIOCHEM: RIFLE ‘Risk’ | RIFLE ‘Injury’ or ‘Failure’ | LOW NOQA=6 | Early: OR 0.361 (95 % CI 0.17–0.78); P = 0.009, Favors Early |

| Shum, 2013 [43] | Retrospective cohort | China | Jan 2008 - Jun 2011 | Age<18, Chronic dialysis, RRT prior to ICU | Sepsis | 120 | 31 | 89 | qEarly 74; Late 73 | Early: SOFA 12- APACHE4=119; Late: SOFA 13- APACHE4=133; P=0.011 | BIOCHEM: sRIFLE-‘pre- Risk’ or ‘Risk’ criteria; Mean time from ICU admit to RRT =20.7hrs, P=0.056 | sRIFLE ‘Injury’ or ‘Failure’ criteria; Mean time from ICU admit to RRT=10.8hrs | LOW NOQA=6 | 28 d mortality: Early-15/31 died (48.4%), Late- 43/89 died (48.3%); P=0.994 |

| Tian, 2014 [46] | Retrospective cohort | China | Nov 2009 - Dec 2011 | Age < 12, Chronic renal disease, Terminal illness,0 Pre-admit CRRT, ICU stay < 72hrs | Sepsis - AKIN 1 | 49 | 23 | 26 | Early 48; Control 54 | Early: SOFA 7.6- APACHE2=12.9; Control: SOFA 8.4- APACHE2=15.3 | BIOCHEM: AKIN 1 (Cr≥26.4μmol/L or >150- 200% baseline & urine <0.5cc/kg/h for >6h) | No RRT (Control): Patients refused CRRT for “personal reasons” | LOW NOQA=6 | 28 d mortality: Early 5/23(22%) died, Control 11/26 (42%) died (NS) |

| Sepsis - AKIN 2 | 52 | 31 | 21 | Early 54; Control 61 | Early: SOFA 9.3- APACHE2=19; Control SOFA 9.6- APACHE2=18.3 | AKIN 2 (Cr>200-300% baseline & urine <0.5cc/kg/h for >12h) | No RRT (Control): Patients refused CRRT for “personal reasons” | 28 d mortality: Early 12/31 (39%) died, Control 14/21 (67%) died; P<0.05 Favors Early | ||||||

| Sepsis - AKIN 3 | 59 | 46 | 13 | Early 50; Control 55 | Early SOFA 10- APACHE2=21.8; Control SOFA 11.2- APACHE2=20.5 | AKIN 3 (Cr≥354μmol/L or Cr>300% baseline w/urine <0.3cc/kg/h for 24h or anuria >12h) | No RRT (Control): Patients refused CRRT for “personal reasons” | 28 d mortality: Early 31/46(67%) died, Control 11/13(85%) died; NS | ||||||

| Serpytis, 2014 [45] | Retrospective cohort | Lithuania | 2007-2011 | NR | Sepsis | 85 | 42 | 43 | All patients mean = 72 NR | NR | TIME: Time from anuria to RRT < 12hrs | Time from anuria to RRT > 12hrs | LOW NOQA=5 | Mortality: Early 30/42 (71%) died, Late 39/43(91%) died; p=0.028; Favors Early |

| Gaudry, 2014 [44] | Retrospective cohort | France | Jan 2004 - Nov 2011 | Age<18, limitation in medical therapy, death<24hrs, chronic renal insufficiency, RRT prior to ICU, kidney transplant, lithium toxicity, multiple myeloma | Sepsis | 203 | 91 | 112 | Early 65; Late 65 | Early: SOFA 9- SAPS2=60; Control SOFA 8- SAPS2=55, P<0.01 | BIOCHEM: RRT criteria: Cr≥300μmol/L, Urea>25mmol/L, K>6.5mmol/L, pH<7.2, Oliguria, Vol overload, | No RRT initiated/Criteria not met for RRT | LOW NOQA=5 | Hosp Mortality: Early 44/91(48%) died, Control (No RRT) 29/112 (26%) died; P<0.001 Favors no RRT |

| Retrospective TOTALS | 2841 | 1434 | 1177 | Pooled mortality: Early 714/1434 (50%), Late 732/1177 (62.2%); n=19 | ||||||||||

LEGEND: AKI Acute kidney injury, AKIN Acute Kidney Injury Network, APACHE Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, Cr Creatinine, CRF Chronic renal failure, CRRT Chronic renal replacement therapy, eGFR Estimated glomerular filtration rate, EHV Early High Volume, ELV Early Low Volume, ESRD End stage renal disease, ICU Intensive Care Unit, LLV Late Low Volume, NOQA Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment, NR Not reported, NSARF National Taiwan University Hospital-Surgical ICU- Acute Renal Failure database, RIFLE Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss and End-stage, RPGN Rapidly progressive glomerularnephritis, SAPS2 Squential Acute physiology Score, SHARF Stuivenberg Hospital Acute Renal Failure Score, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, UOP Urine output

Primary outcome

The observed pooled crude mortality rates varied significantly between the high- and low-quality studies. Among the high-quality studies, the pooled “early” RRT study group mortality rate was 34.6 % (192 of 555) compared with 40.2 % (196 of 487) in the pooled “late” RRT group. The low-quality studies demonstrated a pooled “early” RRT group mortality rate of 51.3 % (1871 of 3645) compared with 54.3 % (1486 of 2737) in the “late” RRT groups. The most frequently reported measurement of illness severity in the studies we analyzed was the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. The SOFA score has been correlated with critical care patient outcomes [47, 48], but it is not as robust as other scoring systems validated in predicting survival (e.g., Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II [APACHE2] or Simplified Acute Physiology Score II [SAPS2]) [49]. The mean weighted SOFA scores in the high-quality studies were 10.2 and 10.4 in the “early” and “late” groups, respectively. SOFA scores were reported for 78 % of patients in the high-quality studies. Among the high-quality studies, the SOFA score appeared to correspond with an APACHE2 score of approximately 20 or a SAPS2 score of approximately 53 when these additional illness severity metrics were reported by the principal investigators. Unfortunately, more detailed quantitative evaluation of illness severity using APACHE2 or SAPS2 scores was not possible, owing to heterogeneous reporting methods between investigators and a lack of sufficient data. SOFA scores were reported for 65 % of the patients in the studies assigned low-quality ratings. The mean weighted SOFA scores in the “early” and “late” groups among the low-quality studies were comparable to those for the high-quality studies at 10.0 and 9.2, respectively. No further comments can be made regarding illness severity scores among the low-quality studies, owing to lack of homogeneous and sufficient data. Illness severity scores for all studies are summarized in Table 1.

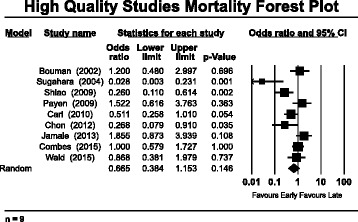

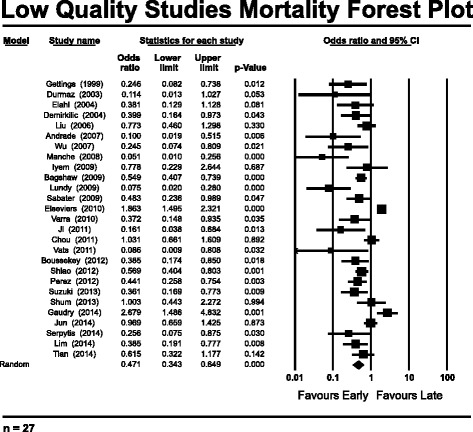

Pooled analysis of the high-quality studies (n = 9) indicates no mortality benefit with “early” versus “late” RRT, with an OR of 0.665 (95 % CI 0.384–1.153, p = 0.146) (Fig. 1). The bulk of the data in support of “early” RRT rests in the pooled low-quality studies (n = 27), with an OR of 0.471 (95 % CI 0.343–0.649, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Similarly to authors of previous meta-analyses, we found very high heterogeneity among studies on this topic. Heterogeneity was highest among the low-quality studies, reflected by a Q value of 163.8, I2 value of 84 %, and τ2 = 0.495 (p < 0.001). Among the high-quality studies, there continued to be statistically significant heterogeneity, with a Q value of 29.1, I2 value of 72.5 %, and τ2 = 0.481 (p < 0.001). Subgroup analysis of the high-quality studies according to ICU admission type and surgical [14, 16, 21] versus mixed medical admissions [7, 12, 15, 17, 35, 40] demonstrated no significant subgroup mortality benefits associated with “early” RRT (see Additional file 4: Figure S3a and b for forest plots by ICU admission type). Subgroup analysis among the high-quality studies was also conducted using the definition of early according to time criteria (hours or days) versus biochemical parameters (i.e., rising creatinine, uremia, oliguria) (see Additional file 5: Figure S4a and b for forest plots by biochemical or time definition of early). There were no significant effects observed in pooled mortality trends in studies that defined early by time criteria rather than on the basis of biochemical parameters.

Fig. 1.

Mortality forest plot of pooled analysis of high-quality studies (n = 9)

Fig. 2.

Mortality forest plot pooled analysis of low-quality studies (n = 27)

Secondary outcomes

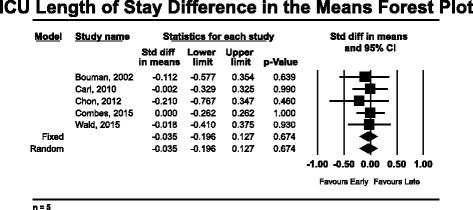

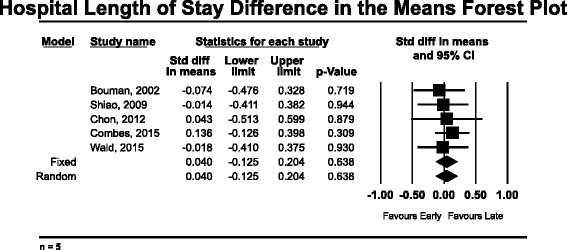

The secondary outcomes analyzed included ICU LOS and hospital LOS. Five of the nine high-quality studies reported ICU LOS data [12, 16, 17, 35, 40]. The mean weighted ICU LOS in the “early” group was 9.4 days (n = 351), compared with 10.8 days (n = 281) in the “late” group. None of the studies reported a significant finding with respect to ICU LOS and “early” RRT. Pooled analysis for ICU LOS also demonstrated no significant change in ICU LOS associated with “early” RRT, with a standard difference in the means of −0.035 (95 % CI −0.196 to 0.127, p = 0.674) using a fixed effects model (Q = 0.598, p = 0.963) (Fig. 3). Hospital LOS was reported in five of nine high-quality studies [12, 16, 17, 21, 40]. The mean weighted hospital LOS in the “early” group was 19.3 days (n = 317), compared with 17.1 days (n = 266) in the “late” group. The pooled hospital LOS data do not reveal any significant difference in hospital LOS using a fixed effects model with a standard difference in the means of 0.040 (95 % CI −0.125 to 0.204, p = 0.638) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of pooled analysis of standard difference of the means for intensive care unit length of stay (n = 5)

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of pooled analysis of standard difference of the means for hospital length of stay (n = 5)

Discussion

Despite several studies having been conducted on this topic over the last 30 years, a clear answer regarding the optimal timing of RRT in critical illness remains elusive. Our analysis does not confirm the conclusions of previous meta-analyses on this topic. Four studies [12, 14, 21, 35] in the high-quality group were previously included in the meta-analysis by Karvellas et al. [9], and only one study [12] was included in the meta-analysis by Seabra et al. [8]. The addition of four recently published studies [15–17, 40] and one high-quality study that was not previously included in meta-analysis [7] accounts for our results that differ from those of earlier authors. Our conclusions build on the concerns raised by both earlier meta-analyses that the results of cohort trials in favor of “early” RRT were not reproduced in methodologically more rigorous study designs (i.e., RCTs). In our further analysis we did not identify critical illness patient subgroups for whom “early” RRT might be more beneficial. Similarly, how one defines early (according to time or on the basis of biochemical characteristics) does not identify a survival advantage associated with “early” RRT compared with usual care. The optimal timing for initiation of RRT is not clarified on the basis of research evaluated to date.

The strength of our present analysis rests on our extensive literature search and strict classification according to study quality to limit risk of type I hypothesis testing error. Prior meta-analyses relied heavily on retrospective cohort study data that possessed incomplete preintervention data or preexisting significant differences in groups which predisposed the investigators to identify a survival difference attributed to “early” RRT that may have been accounted for by the preintervention population differences. We identified differences in the crude mortality rates between the high- and low-quality studies that are incompletely explained. The crude mortality rate differences may be explained by factors that are not adequately controlled for between the groups before the intervention of “early” versus “late” RRT (e.g., unreported regional institutional differences, variation in intensive care resources, institutional setting variability [academic versus community], or natural history variability of the diseases precipitating critical illness). In cohort trials, a difference in preintervention study groups indicates a critical methodological flaw that precludes deriving conclusions from their results. This is referred to as a type I error in hypothesis testing and may falsely attribute differences in outcomes to the study variable rather than the differences between cohorts that existed before analysis. Among high-quality studies, there was no survival advantage to “early” RRT with an OR of 0.665 (p = 0.146). Any inclusion of the low-quality study data would significantly pull the conclusion in favor of “early” RRT, which would represent fulfillment of a type I statistical hypothesis error. The strength of our work is that we vigorously guarded against this possibility.

Subgroup analysis of the high-quality studies did not reveal a survival benefit associated with either a surgical or medical critical care patient population. This conclusion remained the same regardless of whether early was defined by time or on the basis of biochemical parameters. Our secondary outcome analysis was limited by inconsistent and incomplete data reported across studies. Limited pooled analysis of the available data suggested that there was no significant effect on either ICU or hospital LOS associated with “early” RRT. Incomplete data does not permit us to evaluate additional secondary outcomes of interest (such as requirement for mechanical ventilation or rates of renal recovery) that might also be clinically relevant considerations factored into the decision to initiate RRT in critical illness.

By limiting our analysis to studies meeting high-quality criteria, we dismissed a large volume of research on this topic. A critique of our work is that we discarded studies for methodological shortcomings that others may feel should have been included. Most studies (n = 21) in the low-quality group were excluded for incomplete cohort data or significant preintervention differences between cohort groups. The decision to exclude these trials is less controversial than our decision to exclude cohort trials for an NOQA Scale rating less than 7 (n = 6). This is potentially controversial because the NOQA Scale has received criticism regarding its validity and applicability in meta-analysis cohort trial quality assessment [50]. The NOQA Scale has received positive endorsement from some authors [11], but detailed psychometric properties have not been published in peer-reviewed journals to date. Furthermore, our selection of an NOQA Scale rating less than 7 to identify low quality is arbitrary. Our rationale for selecting this cutoff was that it necessitates that at least one of the three NOQA Scale domains be seriously compromised, and we felt that this represented a significant bias predisposing the study results to committing a type I error pattern. Seabra et al. [8] attempted to assign a quality score to trials (0 = lowest quality to 5 = best quality) to evaluate this domain, but their methodology for score assignment was obscure and was not able to be replicated or directly compared with our methods. In qualitative comparison, the study assigned their top score [12] was included in our quantitative analysis; however, their second highest quality study [13] was excluded due to lack of reported illness severity scores between groups. Including studies with methodological errors does not advance scientific understanding of this topic and has contributed to the discordant findings on it.

Early studies on this topic were small and may have overestimated an effect size associated with “early” RRT based on the small size of the study populations. An example of this problem is the Sugahara et al. study [14], where 14-day mortality within the “early” group was 14 % (2 of 14), compared with 86 % (12 of 14) in the “late” group (p < 0.01). While this study was included in our quantitative analysis, the magnitude of the mortality benefit reported in this trial associated with “early” RRT has not been reproduced by subsequent investigators, for reasons that are not clear. In our review of the ongoing trials on this topic registered with the NIH (www.clinicalTrials.gov), we identified three trials [51–53] that may add to knowledge in this area. The methodology of all three active RCTs is roughly similar, with patients randomized from a point in time triggered by the development of biochemical renal injury reflected by a RIFLE grade of “failure” (at least one of rise in creatinine by minimum of 300 %, oliguria less than 0.3 ml/kg/h for 12 h, or anuria lasting more than 12 h). From this biochemical entry point, patients will be randomized to immediate initiation of RRT (goal time to RRT less than 12 h) or standard care (RRT initiated after failure of medical management to temporize metabolic derangements or volume overload). These study designs are similar to the design used by Wald et al. [17], included in our analysis, that was able to separate an “early” group to mean time to RRT of 9.2 h and a “late” RRT group with a mean time to RRT of 32 h after biochemical inclusion criteria were met. Wald et al. [17] did not identify a significant difference in mortality rates between their two groups (p = 0.74). These studies in process will add to the quantity of patients evaluated in this manner and will build on the availability of high-quality data on this topic. By clearly defining routine biochemical criteria associated with acute renal injury, they provide a practical method of renal injury assessment that can be determined by intensivists and nephrologists considering RRT.

Conclusions

The results of our meta-analysis contradict the findings reported by previous authors [8, 9], and we conclude that “early” initiation of RRT in critically ill patients with AKI does not improve survival. This conclusion is derived from the pooled high-quality trial data and excludes data from cohort trials where there were methodological shortcomings that predisposed them to find an effect misattributed to the intervention. Pooled analysis of secondary outcomes did not demonstrate a statistical reduction in ICU or hospital LOS. Additional well-designed RCTs will provide greater confidence in these conclusions as optimal patient care practices progress in critical care. Clinical triggers for the initiation of RRT to optimize patient outcomes have not been clearly identified by current research. Meanwhile, intensivists and nephrologists are encouraged to refrain from lowering their clinical thresholds for implementing RRT in critical care patients with acute renal injury.

Key messages

High-quality trial data do not demonstrate improved survival using an “early” RRT approach in critical illness complicated by AKI.

Lower-quality trial data demonstrate significantly higher mortality rates and form the basis for the bulk of support for “early” AKI.

The optimal time to initiate RRT in critical illness remains undefined.

A conservative approach to initiating RRT in critical illness is supported.

Abbreviations

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- AKIN

Acute Kidney Injury Network

- AMA

against medical advice

- APACHE2

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- Cr

creatinine

- CRF

chronic renal failure

- CRRT

continuous renal replacement therapy

- EHV

early high volume hemofiltration

- ELV

early low volume hemofiltration

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- ICU

intensive care unit

- ISS

illness severity score

- LLV

late low volume hemofiltration

- LOS

length of stay

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NOQA

Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment

- NR

not reported

- NS

not significant

- OR

odds ratio

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- RIFLE

risk, injury, failure, loss of function, and end-stage kidney disease

- RPGN

rapidely progressive glomerulonephritis

- RR

relative risk

- RRT

renal replacement therapy

- SAPS2

Simplified Acute Physiology Score II

- SHARF

Stuivenberg Hospital Acute Renal Failure score below

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- sRIFLE

simple criteria for risk injury failure loss of function and end-stage kidney disease

- UOP

urine output

- NR

not reported

Additional files

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist. (PDF 51 kb)

Search terms used during literature review. (DOCX 15 kb)

Article selection process. (PDF 86 kb)

a Mortality forest plot of subgroup analysis of high-quality studies according to post-surgical ICU admission type (n = 3). b Mortality forest plot of subgroup analysis of high-quality studies according to medical ICU admission type (n = 6). (ZIP 120 kb)

a Mortality forest plot of subgroup analysis of high-quality studies based on the definition of “early” according to time criteria (hours or days) (n = 4). b Mortality forest plot of subgroup analysis of high-quality studies based on the definition of “early” according to biochemical parameters (i.e., rising creatinine, uremia, oliguria) (n = 5). (ZIP 121 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BTW performed the literature search, reviewed studies for inclusion, performed the pooled data analysis using CMA software, and wrote the manuscript. RLCK acted as chair for article review and inclusion, reviewed studies for inclusion, provided senior oversight during manuscript development, and was primary editor of the manuscript during revisions. SK provided oversight for the literature search with the NIH librarian, reviewed studies for inclusion, and contributed to manuscript review. SA, XB, and GWB reviewed studies for inclusion and contributed to manuscript review. All authors contributed to and also read and approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Contributor Information

Benjamin T. Wierstra, Email: bt.wierstra@me.com

Sameer Kadri, Email: sameer.kadri@nih.gov.

Soha Alomar, Email: soha.alomar@gmail.com.

Ximena Burbano, Email: ximena.burbano@zilonis.org.

Glen W. Barrisford, Email: gbarrisford@hotmail.com

Raymond L. C. Kao, Phone: 1-519-685-8500, Email: rkao3@uwo.ca

References

- 1.Ahlström A, Tallgren M, Peltonen S, Räsänen P, Pettilä V. Survival and quality of life of patients requiring acute renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(9):1222–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2681-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagshaw SM, Laupland KB, Doig CJ, Mortis G, Fick GH, Mucenski M, et al. Prognosis for long-term survival and renal recovery in critically ill patients with severe acute renal failure: a population-based study. Crit Care. 2005;9(6):R700–9. doi: 10.1186/cc3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, Venkataraman R, Angus DC, De Bacquer D, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10(3):R73. doi: 10.1186/cc4915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294(7):813–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wald R, Quinn RR, Luo J, Li P, Scales DC, Mamdani MM, et al. Chronic dialysis and death among survivors of acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. JAMA. 2009;302(11):1179–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salisbury PF. Timely versus delayed use of the artificial kidney. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1958;101(4):690–701. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1958.00260160012003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Payen D, Mateo J, Cavaillon JM, Fraisse F, Floriot C, Vicaut E, et al. Impact of continuous venovenous hemofiltration on organ failure during the early phase of severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(3):803–10. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181962316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seabra VF, Balk EM, Liangos O, Sosa MA, Cendoroglo M, Jaber BL. Timing of renal replacement therapy initiation in acute renal failure: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(2):272–84. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.02.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karvellas C, Farhat M, Sajjad I, Mogensen S, Bagshaw S. Timing of initiation of renal replacement therapy in acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis [abstract] Crit Care Med. 2010;38(12 Suppl):A105. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D’Amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C, Song F, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7(27):iii-x, 1-173. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Bouman CS, Oudemans-Van Straaten HM, Tijssen JG, Zandstra DF, Kesecioglu J. Effects of early high-volume continuous venovenous hemofiltration on survival and recovery of renal function in intensive care patients with acute renal failure: a prospective, randomized trial. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(10):2205–11. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200210000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durmaz I, Yagdi T, Calkavur T, Mahmudov R, Apaydin AZ, Posacioglu H, et al. Prophylactic dialysis in patients with renal dysfunction undergoing on-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(3):859–64. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04635-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugahara S, Suzuki H. Early start on continuous hemodialysis therapy improves survival rate in patients with acute renal failure following coronary bypass surgery. Hemodial Int. 2004;8(4):320–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1492-7535.2004.80404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamale TE, Hase NK, Kulkarni M, Pradeep KJ, Keskar V, Jawale S, et al. Earlier-start versus usual-start dialysis in patients with community-acquired acute kidney injury: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(6):1116–21. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Combes A, Bréchot N, Amour J, Cozic N, Lebreton G, Guidon C, et al. Early high-volume hemofiltration versus standard care for post-cardiac surgery shock: the HEROICS Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(10):1179–90. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201503-0516OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wald R, Adhikari NK, Smith OM, Weir MA, Pope K, Cohen A, et al. Comparison of standard and accelerated initiation of renal replacement therapy in acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2015;88(4):897–904. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu KD, Himmelfarb J, Paganini E, Ikizler TA, Soroko SH, Mehta RL, et al. Timing of initiation of dialysis in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):915–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01430406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iyem H, Tavli M, Akcicek F, Buket S. Importance of early dialysis for acute renal failure after an open-heart surgery. Hemodial Int. 2009;13(1):55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bagshaw SM, Uchino S, Bellomo R, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, et al. Timing of renal replacement therapy and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients with severe acute kidney injury. J Crit Care. 2009;24(1):129–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiao CC, Wu VC, Li WY, Lin YF, Hu FC, Young GH, et al. Late initiation of renal replacement therapy is associated with worse outcomes in acute kidney injury after major abdominal surgery. Crit Care. 2009;13(5):R171. doi: 10.1186/cc8147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabater J, Perez XL, Albertos R, Gutierrez D, Labad X. Acute renal failure in septic shock: Should we consider different continuous renal replacement therapies on each RIFLE score stage? [abstract 0924] Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(Suppl 1):S239. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elseviers MM, Lins RL, Van der Niepen P, Hoste E, Malbrain ML, Damas P, et al. Renal replacement therapy is an independent risk factor for mortality in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2010;14(6):R221. doi: 10.1186/cc9355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaara ST, Korhonen AM, Kaukonen KM, Nisula S, Inkinen O, Hoppu S, et al. Early initiation of renal replacement therapy is associated with decreased risk for hospital mortality in the critically ill [abstract] Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(Suppl 1):S9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez X, Sabater J, Huguet M, Santafosta E, Lopez JC, Alonso V, et al. Early timing in septic shock patients [abstract] Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(Suppl 1):S263. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jun M, Bellomo R, Cass A, Gallagher M, Lo S, Lee J. Timing of renal replacement therapy and patient outcomes in the randomized evaluation of normal versus augmented level of replacement therapy study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(8):1756–65. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim CC, Tan CS, Kaushik M, Tan HK. Initiating acute dialysis at earlier Acute Kidney Injury Network stage in critically ill patients without traditional indications does not improve outcome: a prospective cohort study. Nephrology (Carlton) 2015;20(3):148–54. doi: 10.1111/nep.12364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gettings LG, Reynolds HN, Scalea T. Outcome in post-traumatic acute renal failure when continuous renal replacement therapy is applied early vs. late. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25(8):805–13. doi: 10.1007/s001340050956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elahi MM, Lim MY, Joseph RN, Dhannapuneni RR, Spyt TJ. Early hemofiltration improves survival in post-cardiotomy patients with acute renal failure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26(5):1027–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demirkiliç U, Kuralay E, Yenicesu M, Cağlar K, Oz BS, Cingöz F, et al. Timing of replacement therapy for acute renal failure after cardiac surgery. J Card Surg. 2004;19(1):17–20. doi: 10.1111/j.0886-0440.2004.04004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrade L, Cleto S, Seguro AC. Door-to-dialysis time and daily hemodialysis in patients with leptospirosis: impact on mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(4):739–44. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00680207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu VC, Ko WJ, Chang HW, Chen YS, Chen YW, Chen YM, et al. Early renal replacement therapy in patients with postoperative acute liver failure associated with acute renal failure: effect on postoperative outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(2):266–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manche A, Casha A, Rychter J, Farrugia E, Debono M. Early dialysis in acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2008;7(5):829–32. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2008.181909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lundy JB, Chung KK, Wolf SF, Barillo DJ, King BT, White CE, et al. Improvement in mortality in severely burned patients with acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute kidney injury with early continuous venovenous hemofiltration. Blood Purif. 2009;27(3):278–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carl DE, Grossman C, Behnke M, Sessler CN, Gehr TW. Effect of timing of dialysis on mortality in critically ill, septic patients with acute renal failure. Hemodial Int. 2010;14(1):11–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ji Q, Mei Y, Wang X, Feng J, Cai J, Zhou Y, et al. Timing of continuous veno-venous hemodialysis in the treatment of acute renal failure following cardiac surgery. Heart Vessels. 2011;26(2):183–9. doi: 10.1007/s00380-010-0045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chou YH, Huang TM, Wu VC, Wang CY, Shiao CC, Lai CF, et al. Impact of timing of renal replacement therapy initiation on outcome of septic acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2011;15(3):R134. doi: 10.1186/cc10252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vats HS, Dart RA, Okon TR, Liang H, Paganini EP. Does early initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy affect outcome: experience in a tertiary care center. Ren Fail. 2011;33(7):698–706. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2011.589945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boussekey N, Capron B, Delannoy PY, Devos P, Alfandari S, Chiche A, et al. Survival in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury treated with early hemodiafiltration. Int J Artif Organs. 2012;35(12):1039–46. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chon GR, Chang JW, Huh JW, Lim CM, Koh Y, Park SK, et al. A comparison of the time from sepsis to inception of continuous renal replacement therapy versus RIFLE criteria in patients with septic acute kidney injury. Shock. 2012;38(1):30–6. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31825adcda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiao CC, Ko WJ, Wu VC, Huang TM, Lai CF, Lin YF, et al. U-curve association between timing of renal replacement therapy initiation and in-hospital mortality in postoperative acute kidney injury. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki J, Ohnuma T, Sanayama H, Ito K, Fujiwara T, Yamada H, et al. Early initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy is associated with lower mortality in patients with acute kidney injury [abstract] Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(Suppl 2):S443. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shum HP, Chan KC, Kwan MC, Yeung AW, Cheung EW, Yan WW. Timing for initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy in patients with septic shock and acute kidney injury. Ther Apher Dial. 2013;17(3):305–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2012.01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaudry S, Ricard JD, Leclaire C, Rafat C, Messika J, Bedet A, et al. Acute kidney injury in critical care: experience of a conservative strategy. J Crit Care. 2014;29(6):1022–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Serpytis P, Smigelskaite A, Katliorius R, Griskevicius A. The early use of hemofiltration increases survival in patients with acute renal failure in the setting of intensive cardiac care unit [abstract PM046] Glob Heart. 2014;9(1 Suppl):e70. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.1458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tian H, Sun T, Hao D, Wang T, Li Z, Han S, et al. The optimal timing of continuous renal replacement therapy for patients with sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46(10):2009–14. doi: 10.1007/s11255-014-0747-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zygun DA, Laupland KB, Fick GH, Sandham JD, Doig CJ. Limited ability of SOFA and MOD scores to discriminate outcome: a prospective evaluation in 1,436 patients. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52(3):302–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03016068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pettilä V, Pettilä M, Sarna S, Voutilainen P, Takkunen O. Comparison of multiple organ dysfunction scores in the prediction of hospital mortality in the critically ill. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(8):1705–11. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vincent JL, Moreno R. Clinical review: scoring systems in the critically ill. Crit Care. 2010;14(2):207. doi: 10.1186/cc8204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaudry S, Hajage D, Schortgen F, Martin-Lefevre L, Tubach F, Pons B, et al. Comparison of two strategies for initiating renal replacement therapy in the intensive care unit: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial (AKIKI) Trials. 2015;16:170. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0718-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barbar SD, Binquet C, Monchi M, Bruyère R, Quenot JP. Impact on mortality of the timing of renal replacement therapy in patients with severe acute kidney injury in septic shock: the IDEAL-ICU study (Initiation of Dialysis EArly Versus deLayed in Intensive Care Unit): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:270. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith OM, Wald R, Adhikari NK, Pope K, Weir MA, Bagshaw SM, et al. Standard versus accelerated initiation of renal replacement therapy in acute kidney injury (STARRT-AKI): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:320. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]