Abstract

To determine the potential utility of Polygonum hydropiper (tade) as an anti-dementia functional food, the present study assessed the acetylcholinesterase inhibitory and anti-inflammatory activities of tade crude extracts in human cells. Crude extracts of tade were obtained by homogenizing tade in distilled water and then heating the resulting crude extracts. The hot aqueous extracts were purified by centrifugation and freeze-dried. The inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) by tade was investigated quantitatively by Ellman’s method. Furthermore, the in vitro effects on human leukocytes (phagocytic activity, phagosome-lysosome fusion, and superoxide anion release) of coating inactive Staphylococcus aureus cells with tade crude extracts were studied. The tade crude extracts inhibited AChE activity. Furthermore, they increased phagocytic activity and phagosome-lysosome fusion in human neutrophils and monocytes in a nominally dose-dependent manner. However, the tade crude extracts did not alter superoxide anion release (O2−) from neutrophils. Our results confirmed that crude extracts of P. hydropiper exhibit antiacetylcholinesterase and immunostimulation activities in vitro. P. hydropiper thus is a candidate functional food for the prevention of dementia.

Keywords: Polygonum hydropiper, functional food, anti-acetylcholinesterase, phagocytosis, phagosome-lysosome fusion, superoxide anion release

INTRODUCTION

The average age of the population of advanced nations have risen by 30 years or more over the last century [1]. Major causes of this include a decline in the birthrate and improved health. By the year 2050, it is forecast that 32% of the world’s population will be older than 60 years and that 9.5% of Japan’s population will be more than 80 years old [1]. Consequently, the demand for healthcare, medical treatment, welfare, and care, as well as expenses for pensions and social security, will increase significantly. Enabling the elderly to live independent, healthy lives is a very important concern. In the case of an aging population, the risk of diseases such as hypertension, cerebral infarction, and dementia increases due to the age-related impairment of physical conditions and of immune activity. Dementia is an especially large challenge for aging populations.

Dementia (neurocognitive disorders, NCDs) is classified into several types and can be associated with Alzheimer’s disease, cerebrovascular accident after apoplexy, dementia with Lewy bodies, and Parkinson’s disease. Alzheimer’s dementia is a progressive illness with features such as diminishing memory and judgment capability, emotional instability, and a loss of physical ability [2].

Recently, as research on the risk factors of dementia has progressed, it has become clear that a shortage of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) is one of the causes of the decline in thinking power and a cognitive obstacle within the brain to memory and learning [3].

One method for preventing dementia is maintaining the concentration of ACh in the central nervous system. Treatment approaches have included supplementation with acetylcholine precursors, muscarinic agonists, nicotinic agonists, and AChE inhibitors [4,5,6,7].

A nicotinic acetylcholine receptor exists in the axial fiber of the acetylcholine nerve; this component of the cerebral cortex emits acetylcholine [8, 9].

In previous work, we reported that prophylactic administration of Polygonum tinctorium (intraperitoneally at 40 mg/kg or orally at 10–40 mg/kg) protected mice from nicotine-induced mortality [10]. In separate work, Ayaz et al. reported that organic solvent extracts of a related plant (Polygonum hydropiper) displayed AChE inhibitory activities [11].

Based on these results, we decided to investigate the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitory activity of extracts of P. hydropiper. P. hydropiper is an edible plant that is widely distributed in Asia and Japan. We focused on a specific P. hydropiper variant, referred to as tade, which is used as a spice in certain types of Japanese food. Since P. hydropiper had multiple uses, we suspected that the P. hydropiper extract studied by Ayaz et al. [11] had an active ingredient distinct from that in tade.

In order to prolong healthy life expectancy, basic research for promoting clinical application is required. For that purpose, it is important to establish alternative methods that can supplement or replace standard medical treatments. Notably, in recent years various substances have been proposed as functional foods for prevention of dementia [12,13,14,15]. We hypothesized that P. hydropiper (tade or extracts thereof) might serve as foods for prevention of lifestyle-related diseases resulting in NCDs. Specifically, we tested whether P. hydropiper might serve as a functional food for the prevention of dementia. Additionally, given the potential difficulty in using a sample extracted with an organic solvent as a dietary food, we focused on the activities associated with a water-soluble fraction.

To evaluate the possibility of P. hydropiper (tade) as a dietary food for prevention of dementia, we evaluated the inhibition of AChE and immunostimulation by a tade crude extract. Notably, it has been reported that acetylcholine may suppress inflammatory responses within the nervous system [16]. Therefore we investigated whether P. hydropiper extracts that have AChE inhibitory activities also influence immune response, thereby suppressing inflammation.

Phagocytosis serves as the first step in the human defense system against various infections. Phagosomes fuse with lysosomes to permit degradation of ingested particles in human phagocytic cells. The intracellular killing process of neutrophils produces reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide anions. Excess superoxide anion injures tissues in the living body and weakens the body’s resistance; thus, it is important to study whether the proper quantity of superoxide anion is being produced. Since antioxidants are potentially important for the prevention of dementia, the superoxide anion values of tade were also measured.

Therefore, to evaluate the potential of crude extracts from P. hydropiper L. as functional foods, we investigated the AChE inhibitory and anti-inflammatory activities of tade crude extracts in human cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and purification of the material

P. hydropiper (also referred to as Japanese water pepper; Japanese common name: tade) is eaten as a spice in Japan as part of Japanese-style food. The material used here consisted of both green leaves (referred to as Ayutade in Japanese) and young red sprouts (referred to as Benitade in Japanese). Ayutade was grown in Osaka, and Benitade was grown in Hiroshima; both types of tade were grown as foods and were obtained from the Kyoto Nishiki market in Japan.

The P. hydropiper material was homogenized in a cooking juicer with 10 volumes of distilled water. The extracts were heated at 80°C for 10 min and subjected to centrifugation (4°C, 5,000×g for 30 min) to pellet out particulate matter. The supernatant fluids were lyophilized and powdered. The freeze-dried tade powder corresponded to 1.4% by weight of the P. hydropiper material used for homogenization. This powder was dissolved with distilled water on the day of the experiment. Separate extracts were generated from the Ayutade and Benitade.

Estimation of acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activities

The inhibition of AChE by the tade crude extracts was evaluated spectrophotometrically with a Hitachi U-2000 spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Specifically, AChE inhibition was assessed by using acetylthiocholine iodide as a substrate, per the Ellman assay [17]. Crude extracts of tade were tested at a range of concentrations (100–600 µg/ml and 100–500 µg/ml for the Ayutade and Benitade extracts, respectively). The reaction of tade crude extract and 10 mM (4 mg/ml) 5,5-dithio-bis-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) was confirmed by the formation of thionitrobenzoate (TNB) at 37°C using 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 8) containing AChE.

After incubating the suspension without the substrate for 30 sec in a cell, the substrate was added; the reaction was allowed to initiate for 30 sec, and the absorbance value at 412 nm was subsequently recorded for 2.5 min. The absorbance values at 412 nm (the formation of TNB) were measured with a spectrophotometer. The absorbance value of TNB was calculated using the equation E412 nm = 1.55×104 M−1cm−1. For this calculation, an extinction coefficient of 13600 M−1cm−1 was used. The Km value of the AChE inhibitor was 0.1703 mM.

A reaction mixture consisting of the same ingredients without either tade crude extract was used as a control. Percentages of enzyme inhibition were calculated using the equation AChE inhibition = 100(control) – %enzyme activity.

Since galanthamine is indicated for the treatment of mild to moderate vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s [18,19,20,21], this compound was used as a positive control for AChE inhibition.

Preparation of neutrophils or monocytes

Human neutrophils and monocytes from heparin-treated venous blood of healthy donors were isolated with Mono-Poly Resolving Medium (DS Pharma Biomedical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) by centrifugation at 400×g for 30 min. Neutrophils and monocytes were washed three times with RPMI 1640 medium containing 100 U/ml of penicillin G and 100 µg/ml of streptomycin and then resuspended at a concentration of 5×106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. The neutrophils (1×106 cells) were incubated on a cover slip for 90 min at 37°C and then washed three times with RPMI 1640 medium to remove the adherent cells, as previously described [22,23,24,25,26]. Human monocytes were isolated using the same method as for the neutrophils.

Estimation of phagocytosis

The influences of tade crude extracts on phagocytosis and phagosome-lysosome fusion by human leukocytes were evaluated using inactive Staphylococcus aureus cells coated with tade in vitro, as previously described [22,23,24,25,26].

S. aureus 209P was grown in a nutrient agar at 37°C for 24 hr and then killed by autoclaving. The isolated tade crude extracts (20–100 µg/ml) were mixed with the heat-killed cell suspension of S. aureus 209P (1×108 cells/ml) and then suspended in 0.1% gelatin-Hanks buffer by mixing vigorously. Phagocytosis was initiated by the addition of 200 µl of tade-coated killed S. aureus suspension to the neutrophil (monocyte) culture (5×106 cells/ml) on cover slips. After incubation for 60 min (neutrophils) or 3 h (monocytes) at 37°C, the cover slips were washed three times with RPMI 1640 medium, and neutrophils and monocytes were fixed with methanol, followed by staining with methylene blue. The tade-coated S. aureus that had been phagocytosed by neutrophils or monocytes were observed under a microscope. A total of one hundred and twenty leukocyte cells were examined at random, and the number of phagocytosed bacteria per leukocyte cell was counted.

Estimation of the phagosome-lysosome fusion rate

Phagosome-lysosome fusion by neutrophils was assayed using the same method as described for the study of phagocytosis after the neutrophils were prelabeled with acridine orange (5 µg/ml) on cover slips for 15 min at 37°C [22,23,24,25,26]. Phagosome-lysosome fusion was initiated by the addition of killed S. aureus cells coated with tade crude extract (1:10 ratio of neutrophils to bacteria) in a total volume of 200 µl of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. After incubation for 60 min, the cover slips were washed three times with RPMI 1640 medium and allowed to air-dry. Phagosome-lysosome fusion was determined by observing acridine orange-stained bacteria under a fluorescence microscope at an emission wavelength of 520 nm. A total of 100 neutrophil cells were examined at random, and the number of bacteria per neutrophil was calculated. The fusion index was defined as the percentage of positive fusion multiplied by the mean number of fused phagosomes per neutrophil.

Determination of superoxide anion production by neutrophils

Generation of superoxide anion (O2–) by neutrophils was measured on the basis of superoxide-induced cytochrome c reduction as described previously [22,23,24,25,26]. The standard reaction mixture contained 80 μM cytochrome c, neutrophils at 1×106 per ml, and tade-coated S. aureus at 5×107 cells per ml in a total volume of 1.0 ml of HEPES- saline buffer (pH 7.2). After incubation for 60 min at 37°C, the suspension was centrifuged at 5,000×g for 1 min. The absorbance at 550 nm of each supernatant solution was measured using a microplate reader. The value of the cytochrome c reduction was calculated from the equation E550 nm = 2.1×104 M−1cm−1, where E550 nm was the molar extinction coefficient at 550 nm. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate solution (PMA) was used as the positive control; PMA plus superoxide dismutase (SOD) was used as the negative control. These negative control reactions used 200 pg PMA and 40 pg SOD in a total volume of 1.0 ml of HEPES-saline buffer.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and values were expressed as the mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA followed by a two-tailed multiple comparison t-test was used for comparison of the uncoated control with the test groups. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The Tukey-Kramer test was used when comparing among pairs of groups. The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Kyoto Women’s University and carried out in accordance with the code of ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

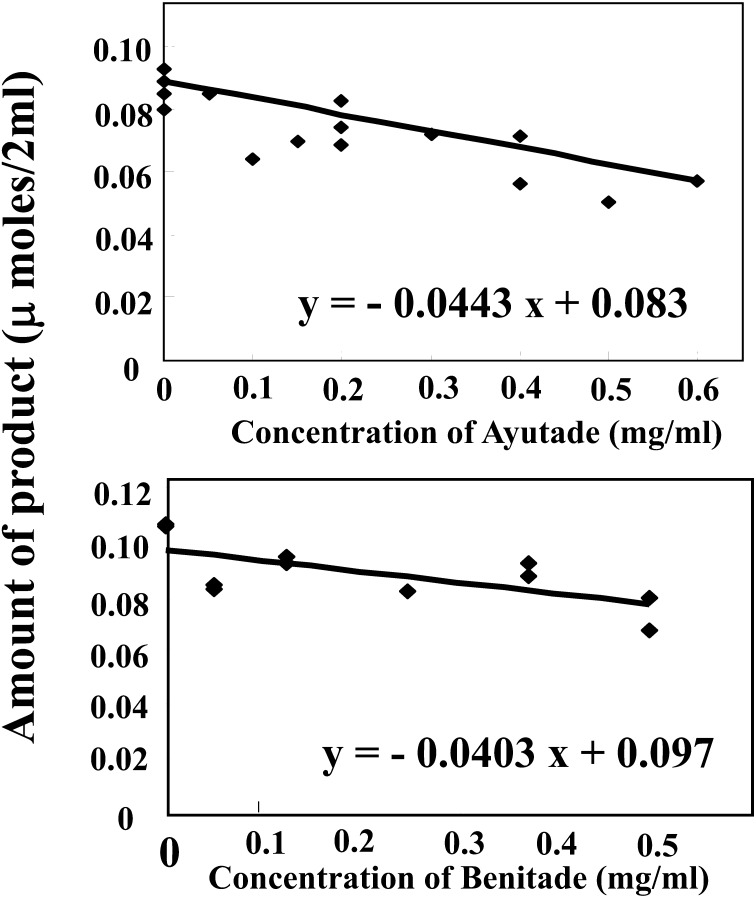

The inhibition of AChE by tade crude extracts was assessed using the Ellman method (Fig. 1). Inhibition of AChE activity by the Ayutade crude extract fit the equation y = –0.0443x + 0.0833, and that by the Benitade crude extracts fit the equations y = –0.0403x + 0.097, showing that tade components inhibited AChE activity.

Fig. 1.

Effects of Ayutade and Benitade crude extracts on acetylcholinesterase activity.

The inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by Polygonum hydropiper crude extracts was studied quantitatively using the Ellman method with acetylthiocholine iodide as the substrate.

The degree of AChE inhibitory activity (%) caused by tade crude extracts was calculated using the respective formulae derived in Fig. 1. The results of AChE inhibition by tade crude extracts at 100–600 µg/ml are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. AChE inhibition by tade crude extracts.

| Sample | Concentration (μg/ml) |

AChE inhibition (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ayutade | 100 | 6.3 ± 2.4 |

| 200 | 10.7 ± 6.7 | |

| 300 | 16.0 ± 0.7 | |

| 400 | 21.3 ± 7.3 | |

| 500 | 26.6 ± 4.9 | |

| 600 | 31.9 ± 0.7 | |

| Benitade | 100 | 4.1 ± 3.7 |

| 200 | 8.4 ± 2.1 | |

| 300 | 12.5 ± 0.6 | |

| 400 | 16.6 ± 1.0 | |

| 500 | 20.8 ± 2.6 | |

| Galanthamine (standard) | 50 | 50.0 ± 2.3 |

| 300 | 84.0 ± 0.4 | |

The effects of tade crude extracts on AChE inhibition were calculated using the corresponding formulae derived in Fig. 1. Galanthamine was used as a positive control for AChE inhibition. Values represent the mean ± SD (n=3).

AChE inhibition by tade was nominally dose dependent. The effects of AChE inhibition were about 15 to 19% of the standard reagent galanthamine at the concentration of 300 µg/ml (Table 1).

Ayutade crude extract at the highest tested concentration (600 µg/ml) yielded 31.9% inhibition of AChE, whereas the AChE inhibitory activity of Benitade crude extract was lower than that of the Ayutade at the respective concentrations. Thus, Ayutade appeared to be more potent than Benitade. Considered together, the results indicated that tade crude extracts exhibited AChE inhibitory activity.

Our results suggested a weaker inhibitory activity than that of Ayaz et al., who reported an AChE inhibition IC50 of 35 µg/ml with the hexane fraction of P. hydropiper [11]. Notably, and in contrast to the Ayaz et al. extract, our tade crude extracts represented hot water-soluble ingredients. Nonetheless, our results indicated that the tade water-soluble fraction does possess AChE inhibitory activity.

Next, to evaluate the potential utility of P. hydropiper (tade) as an anti-dementia functional food, a long-term administration trial of dietary intake will be necessary. Therefore we examined whether tade crude extracts influenced the immune response of human leukocytes, a cell type that serves as the first step in the human defense system in the case of dietary intake. As an index of immunoactivity, we evaluated the in vitro effects of P. hydropiper extracts on phagocytosis, phagosome-lysosome fusion, and superoxide anion production by human neutrophils and monocytes.

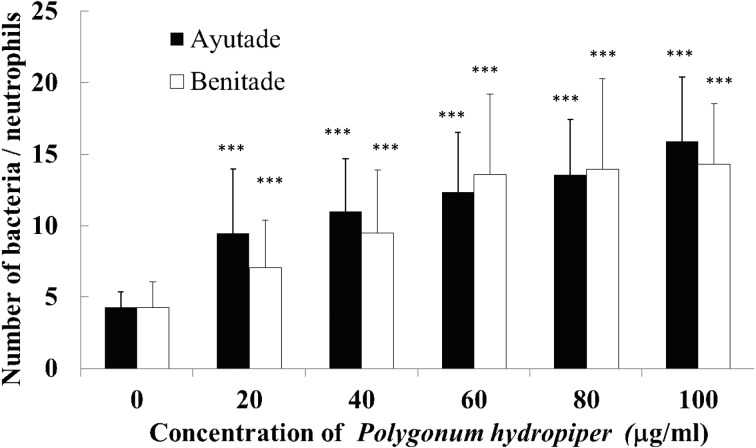

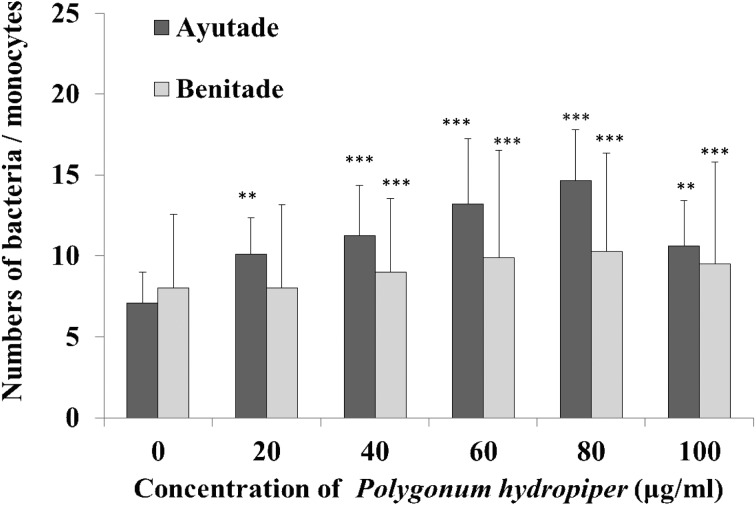

Phagocytic activity was assessed in the presence of tade crude extracts at concentrations ranging from 10–100 µg/ml (Fig. 2). Coating of S. aureus with Ayutade or Benitade crude extract yielded significant (3.7- and 3.3-fold, respectively) increases in phagocytosis by neutrophils compared with phagocytosis of uncoated S. aureus. Similarly, coating of S. aureus with Ayutade or Benitade crude extract yielded significant (2.0- and 1.3-fold, respectively) increases in phagocytosis by monocytes (Fig. 3). Thus, both of the tade crude extracts stimulated phagocytosis by human neutrophils and monocytes. As seen for AChE inhibition, the Ayutade crude extract appeared to be more potent than the Benitade extract.

Fig. 2.

Effects of tade crude extracts on phagocytosis by human neutrophils.

Values represent the mean ± SD. ***p<0.001, significantly different from control.

Fig. 3.

Effects of tade crude extracts on phagocytosis by human monocytes.

Values represent the mean ± SD. **p<0.01, significantly different from control; ***p<0.001, significantly different from control.

These results are consistent with the activity reported for another plant of the Polygonum genus. Specifically, Chueh et al. reported that a crude extract of P. cuspidatum (Itadori) promotes in vivo immune responses in leukemic mice by enhancing the phagocytotic activities of macrophages and natural killer cells [27, 28].

Therefore, the effect of Ayutade crude extract on the phagosome-lysosome fusion rate in neutrophils was studied further. The fusion index (FI) was defined as the percentage of positive fusions multiplied by the mean number of fused phagosomes per neutrophil. The FI following coating with the Ayutade crude extract was approximately 12-fold higher than that seen with the uncoated control (Fig. 4), demonstrating stimulation of both phagocytosis and phagosome-lysosome fusion with the Ayutade crude extract.

Fig. 4.

Effect of Ayutade crude extracts on phagosome-lysosome fusion by neutrophils. Fusion index was defined as the percentage of positive fusion multiplied by the mean number of fused phagosomes per cell. Values represent the mean ± SD.

*p<0.05, significantly different from control; **p<0.01, significantly different from control.

The ratios of the FI to the phagocytic index (PI) for human neutrophils are presented in Table 2. At all of the tested concentrations, 25% of the phagocytosed bacterial cells were degraded following lysosomal fusion of the phagosome.

Table 2. Fusion/phagocytic index ratio in human neutrophils exposed to Ayutade crude extracts.

| Concentration | FI | PI | FI/PI |

|---|---|---|---|

| (μg/ml) | |||

| 0 | 21.1 | 153.3 | 0.138 |

| 20 | 63.7 | 290.9 | 0.219 |

| 40 | 131.7 | 563.0 | 0.234 |

| 60 | 172.8 | 738.0 | 0.234 |

| 80 | 214.5 | 842.0 | 0.255 |

| 100 | 252.7 | 933.0 | 0.271 |

The fusion index (FI) was defined as the percentage of positive fusions multiplied by the mean number of fused phagosomes per neutrophil. The phagocytic index (PI) was defined as the percentage of positive phagocytosis multiplied by the mean number of phagocytosed bacteria per neutrophil.

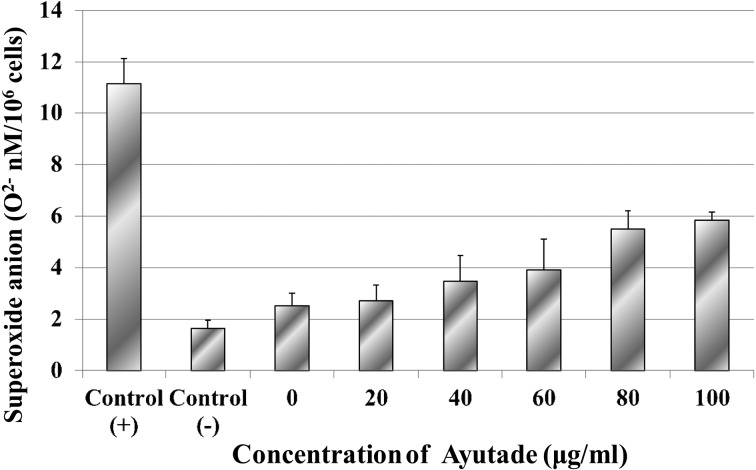

In the process of human immune response, natural antioxidants (such as free radical scavengers) may be employed [29]. The intracellular process of killing neutrophils produces ROS such as superoxide anions and hydroxyl radicals. Excess superoxide anion injures tissues in the living body and weakens the body’s resistance; thus, it is important to study whether the proper quantity of superoxide anion is being produced. Therefore, the effects of P. hydropiper crude extracts on superoxide anion release (O2–) from neutrophils were examined (Fig. 5). It was found that coating of S. aureus cells with Ayutade crude extract yielded nominal but nonsignificant increases in superoxide anion production by neutrophils, even at the highest tested Ayutade concentration of 100 µg/ml. Thus, the AChE inhibitory component of the P. hydropiper crude extract did not induce increased superoxide anion release from neutrophils. Although tade crude extracts enhance phagocytosis and lysosomal fusion, these effects apparently are not associated with increased ROS production.

Fig. 5.

Effect of Ayutade crude extracts on superoxide anion release from human neutrophils. Results are shown as the mean ± SD of three different experiments.

Results were not significantly different from those of the (–) controls.

In control experiments, we measured the effect of galanthamine on phagocytosis by human neutrophils; this compound is employed as a mild treatment for vascular dementia. Coating of S. aureus with galanthamine yielded significant (64.9% at 2.9 µg/ml) inhibition of phagocytosis by neutrophils compared with phagocytosis of uncoated S. aureus (data not shown). Thus, galanthamine inhibited immunoactivity, suggesting that it might exhibit side effects on the human defense system. In contrast, this activity was not seen with the tade crude extracts, suggesting that dietary intake of tade may be better tolerated than that of galanthamine as a potential functional food for the prevention of dementia.

In summary, aqueous crude extracts of P. hydropiper harbor an inhibitor of AChE activity; the extracts also enhanced phagocytosis and phagosome-lysosome fusion by human neutrophils and monocytes but did alter superoxide anion production by these types of cells.

Given that the prevention of lifestyle-related diseases such as cerebral infarction is the subject of wide investigation, P. hydropiper is a candidate potential functional food for the prevention of dementia. Clinical trials for the use of P. hydropiper as a functional food should be initiated.

CONCLUSION

Our results confirmed that crude extracts of P. hydropiper exhibit antiacetylcholinesterase and immunostimulation activities in vitro. P. hydropiper thus is a candidate functional food for the prevention of dementia.

Acknowledgments

This study was generously supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research. The author thanks Dr. Hiroshi Doi of Mukogawa Women’s University for supporting the development of the AChE activity experimental methodology. The author also thanks Manami Nakanishi, Fumika Chiba, and Mika Takahashi of the Kyoto Women’s University for technical support.

References

- 1.Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. 2013. World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision: 31 New York. http://esa.un.org/wpp/documentation/pdf/wpp2012_highlights.pdf (accessed 2015-07-11)

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition-5 (DSM-5), Nurocognitive disorders 591–644. http://www.terapiacognitiva.eu/dwl/dsm5/DSM-5.pdf (accessed 2015-07-29)

- 3.Cutler NR, Sramek JJ. 1998. The role of bridging studies in the development of cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs 10: 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishibashi M, Yamazaki Y, Miledi R, Sumikawa K. 2014. Nicotinic and muscarinic agonists and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors stimulate a common pathway to enhance GluN2B-NMDAR responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 12538–12543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher A. 2008. Cholinergic treatments with emphasis on m1 muscarinic agonists as potential disease-modifying agents for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 5: 433–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akhondzadeh S, Abbasi SH. 2006. Herbal medicine in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 21: 113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimohama S, Taniguchi T, Fujiwara M, Kameyama M. 1986. Changes in nicotinic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors in Alzheimer-type dementia. J Neurochem 46: 288–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Decker MW, Majchrzak MJ. 1992. Effects of systemic and intracerebroventricular administration of mecamylamine, a nicotinic cholinergic antagonist, on spatial memory in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 107: 530–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitehouse PJ, Martino AM, Wagster MV, Price DL, Mayeux R, Atack JR, Kellar KJ. 1988. Reductions in [3H]nicotinic acetylcholine binding in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: an autoradiographic study. Neurology 38: 720–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyazaki Y, Matsuda S, Aki O. 2005. Patent application 2005-126125/2005.4.25, A toxic mitigation action of nicotine in Polygonum tinctorium Lour.

- 11.Ayaz M, Junaid M, Ahmed J, Ullah F, Sadiq A, Ahmad S, Imran M. 2014. Phenolic contents, antioxidant and anticholinesterase potentials of crude extract, subsequent fractions and crude saponins from Polygonum hydropiper L. BMC Complement Altern Med 14: 145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakajima A, Ohizumi Y, Yamada K. 2014. Anti-dementia activity of Nobiletin, a citrus flavonoid: a review of animal studies. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 12: 75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohizumi Y.2015. A new strategy for preventive and functional therapeutic methods for dementia — Approach using natural products—. YAKUGAKU ZASSHI (The Pharmaceutical Society of Japan) 135: 449–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossi C, Ed Dami T, Rigacci S, Stefani M, Luccarini I, Casamenti F. 2014. Employing Alzheimer disease animal models for translational research: focus on dietary components. Neurodegener Dis 13: 131–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abuznait AH, Qosa H, Bussnena BA, Ei Sayed KA, Kaddoumi A. 2013. Olive-oil-derived oleocanthal enhances β-amyloid clearance as a potential neuroprotective mechanism against Alzheimer’s disease: in vitro and in vivo studies. ACS Chem Neurosci 4: 973–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, Amella CA, Tanovic M, Susarla S, Li JH, Wang H, Yang H, Ulloa L, Al-Abed Y, Czura CJ, Tracey KJ. 2003. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature 421: 384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Jr, Feather-Stone RM. 1961. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol 7: 88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinrich M, Lee Teoh H. 2004. Galanthamine from snowdrop—the development of a modern drug against Alzheimer’s disease from local Caucasian knowledge. J Ethnopharmacol 92: 147–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinrich M. 2004. Snowdrops: The heralds of spring and a modern drug for Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmaceutical Journal 273: 905–906. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott LJ, Goa KL. 2000. Galantamine: a review of its use in Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs 60: 1095–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenblatt HM, Kryger G, Lewis T, Silman I, Sussman JL. 1999. Structure of acetylcholinesterase complexed with (-)-galanthamine at 2.3 A resolution. FEBS Lett 463: 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyazaki Y, Kusano S, Doi H, Aki O. 2005. Effects on immune response of antidiabetic ingredients from white-skinned sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.). Nutrition 21: 358–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyazaki Y, Oka S, Hara-Hotta H, Yano I. 1993. Stimulation and inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocytes phagocytosis by lipoamino acids isolated from Serratia marcescens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 6: 265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyazaki Y, Oka S, Yamaguchi S, Mizuno S, Yano I. 1995. Stimulation of phagocytosis and phagosome-lysosome fusion by glycosphingolipids from Sphingomonas paucimobilis. J Biochem 118: 271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguchi S, Miyazaki Y, Oka S, Yano I. 1996. Stimulation of phagocytosis and phagosome-lysosome (P-L) fusion of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes by sulfatide (galactosylceramide-3-sulfate). FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 13: 107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaguchi S, Miyazaki Y, Oka S, Yano I. 1997. Stimulatory effect of gangliosides on phagocytosis, phagosome-lysosome fusion, and intracellular signal transduction system by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Glycoconj J 14: 707–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chueh FS, Lin JJ, Lin JH, Weng SW, Huang YP, Chung JG. 2015. Crude extract of Polygonum cuspidatum stimulates immune responses in normal mice by increasing the percentage of Mac3positive cells and enhancing macrophage phagocytic activtty and natural killer cell cytotoxicity. Mol Med Rep 11: 127–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chueh FS, Lin JJ, Lin JP, Yu FS, Lin JH, Ma YS, Huang YP, Lien JC, Chung JG. 2015. Crude extract of Polygonum cuspidatum promotes immune responses in leukemic mice through enhancing phagocytosis of macrophage and natural killer cell activities in vivo. In Vivo 29: 255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halliwell B. 1994. Free radicals, antioxidants, and human disease: curiosity, cause, or consequence? Lancet 344: 721–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]