Abstract

Purpose

To estimate the overall survival (OS) impact from increasing time to treatment initiation (TTI) for patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).

Methods

Using the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB), we examined patients who received curative therapy for the following sites: oral tongue, oropharynx, larynx, and hypopharynx. TTI was the number of days from diagnosis to initiation of curative treatment. The effect of TTI on OS was determined by using Cox regression models (MVA). Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) identified TTI thresholds via conditional inference trees to estimate the greatest differences in OS on the basis of randomly selected training and validation sets, and repeated this 1,000 times to ensure robustness of TTI thresholds.

Results

A total of 51,655 patients were included. On MVA, TTI of 61 to 90 days versus less than 30 days (hazard ratio [HR], 1.13; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.19) independently increased mortality risk. TTI of 67 days appeared as the optimal threshold on the training RPA, statistical significance was confirmed in the validation set (P < .001), and the 67-day TTI was the optimal threshold in 54% of repeated simulations. Overall, 96% of simulations validated two optimal TTI thresholds, with ranges of 46 to 52 days and 62 to 67 days. The median OS for TTI of 46 to 52 days or fewer versus 53 to 67 days versus greater than 67 days was 71.9 months (95% CI, 70.3 to 73.5 months) versus 61 months (95% CI, 57 to 66.1 months) versus 46.6 months (95% CI, 42.8 to 50.7 months), respectively (P < .001). In the most recent year with available data (2011), 25% of patients had TTI of greater than 46 days.

Conclusion

TTI independently affects survival. One in four patients experienced treatment delay. TTI of greater than 46 to 52 days introduced an increased risk of death that was most consistently detrimental beyond 60 days. Prolonged TTI is currently affecting survival.

INTRODUCTION

The interval from diagnosis to the time of curative treatment initiation (TTI) is increasing in the United States for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).1 Rising TTI reflects increased use of sophisticated diagnostic and therapeutic techniques, increasing transitions in care, and perhaps a provider shortage.2-4 Because the Institute of Medicine cites timeliness of care as a quality indicator5 to serve as a surrogate for the availability of resources and health system efficiency,6 the clinical ramifications of increasing TTI warrant investigation.

HNSCC serves well for an investigation of the clinical effects of TTI. Tumors proliferate rapidly, and deferred treatment can result in stage progression7,8 and worsen survival.9 Although increasing TTI to permit sophisticated and personalized therapy may improve efficacy, it is unknown whether a threshold exists beyond which increasing TTI adversely affects outcomes. This study analyzed a large national registry to estimate the impact of increasing TTI on survival for patients with HNSCC in the United States.

METHODS

The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB), a joint program of the Commission on Cancer (CoC) and the American Cancer Society, is a nationwide oncology database that contains information about patterns of cancer care and treatment outcomes. The NCDB has collected data on newly diagnosed cancers since 1985 and includes information about more than 29 million cancers from greater than 1,500 hospitals with CoC-accredited programs in the United States and Puerto Rico. Approximately 70% of new cancer occurrences in the United States diagnosed and treated each year are reported to the NCDB.10

Patient Selection

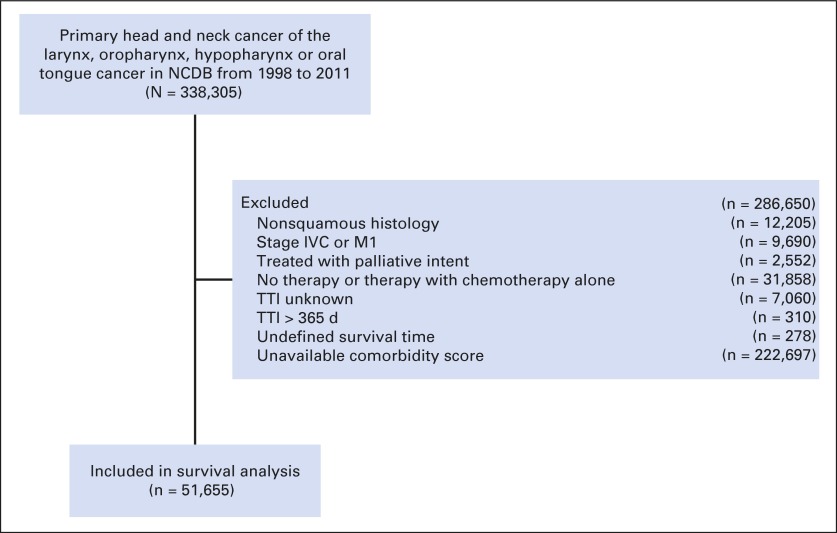

Access was granted to the NCDB for the following disease sites from 1998 to 2011: oral tongue, oropharynx, larynx, and hypopharynx. Patients with HNSCC were identified on the basis of International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3) site codes (8000, 8053, 8070, 8071, 8072, 8076, 8082, 8083, 8084, 8052, 8074, 8023, 8430, and 8560). We included patients with HNSCC who were treated with curative intent by surgery, radiation therapy (RT), chemoradiation (CRT), or a combination of these modalities. TTI was defined as time from date of diagnosis to date when curative therapy began. The date of diagnosis is coded as that of the most definitive method of diagnostic confirmation on the basis of histologic, cytologic, or immunohistochemical confirmation from biopsy specimens in the patient’s record. Surgical codes from the Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards manual identified definitive therapeutic surgical procedures for each subsite. Surgical procedures that were not designed to extirpate tumor (eg, gastrostomy tube placement, tracheostomy) were excluded, as were the following: distant metastatic disease (stage IVC), TTI greater than 365 days from diagnosis date, nonsquamous histology, unknown stage, therapy with palliative intent (specifically coded in the NCDB by treating institution), treatment with chemotherapy alone, and incomplete data about days from diagnosis to treatment (Fig 1). We excluded patients with TTI of greater than 365 days because of concerns surrounding miscoding; their records were unlikely to reflect true upfront definitive therapy. The NCDB documents whether diagnosis and first course of definitive treatment were performed at different hospitals. A care transition was defined as a change in facility from diagnosis to definitive treatment.

Fig 1.

Diagram of analytic cohort for survival analysis. NCDB, National Cancer Data Base; TTI, time to treatment initiation.

The primary outcome was overall survival (OS). NCDB does not collect information on recurrence or cancer-specific survival. Because of competing risks of death for patients with HNSCC,11 examination of OS without adjustment for comorbidity may confound results. Charlson/Deyo comorbidity scores together with survival status are available only for a limited period of 2003 to 2005. We therefore limited this survival analysis to 2003 to 2005 to control for non-HNSCC death. To avoid survivorship bias, survival time was defined as time from initiation of last modality of definitive initial treatment until death or loss to follow up.12 Baseline demographic information is available for all patients from 1998 through 2011.

Statistical Methods

Covariates available for adjustment include race, Hispanic ethnicity, age, insurance, urban/rural status, median income, education level (defined as estimated number of adults in a patient’s zip code who did not graduate from high school), comorbidity score, tumor site, cancer stage, treatment modality, care transitions, facility type, distance from facility, and TTI. The Charlson/Deyo score was truncated to 0 (no comorbid conditions reported), 1, or 2 (greater than 1 comorbid conditions reported). Each reporting facility was classified as one of four types: community, comprehensive community, academic/research program (includes National Cancer Institute–designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers), or other. Facilities categorized as other included Veterans Affairs, hospital associate cancer program (fewer than 100 newly diagnosed occurrences/year), and nonhospital–based free-standing cancer center programs that offer at least one cancer-related treatment modality. Discrimination between facility types categorized as other was not possible.

We categorized TTI into four prespecified groups: 0 to 30 days, 31 to 60 days, 61 to 90 days, and greater than 90 days, and tested differences according to covariates by using χ2 tests. Kaplan-Meier methods estimated OS and were compared by using log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to account for the effects of patient, tumor, and treatment factors; all available covariates were included in the model. We tested proportional hazards assumption by using Schoenfeld residuals and models with time-varying hazards. We explored interactions between TTI and stage, facility type, treatment modality, cancer subsite, and care transitions. These interactions were included in a combined-effects subgroup model if they showed overall significance by using the multivariable Wald test. Significant interactions were subsequently added individually to the full model to assess individual moderation effects.

Two separate recursive partitioning analyses (RPAs) were performed to identify optimal TTI thresholds at which OS differences were greatest by using exponential scaling.13 In the first RPA, a training set from a random sampling of 50% of the cohort served to identify an optimal threshold to estimate the impact of TTI on OS. These thresholds were applied to an independent validation cohort (the remaining randomly sampled 50% of the cohort) to assess reproducibility in estimating OS. To test additional robustness of these thresholds, a second RPA was repeated with 1,000 simulated conditional inference trees, which each were based on random sampling of 50% of the cohort. Significant thresholds were identified on the basis of the most common first two TTI splits of the partitioned data. All analyses were performed in SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and STATA (version 12.1, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Baseline Population Demographics

A total of 51,655 patients with HNSCC from 2003 through 2005 met inclusion criteria, and their characteristics are summarized in 30-day intervals (Table 1). Median follow-up time was 84 months (range, 0 to 120.5 months). TTI varied significantly with stage (median TTI, 20 days, 26 days, 27 days, and 28 days for stages I, II, III, and IV, respectively; P < .001), treatment modality (median TTI, 17 days, 31 days, and 34 days for surgery alone, RT, and CRT, respectively; P < .001), and primary site (median TTI, 23 days, 26 days, 28 days, 29 days, and 30 days for larynx, tonsil, oral tongue, hypopharynx, and nontonsil oropharynx, respectively; P < .001). Academic facilities had significantly higher median TTI (28 days) compared with comprehensive community and community programs, (23 days and 22 days, respectively; P < .001) and the highest percentage of patients transitioning care, a factor independently associated with increasing TTI.1 Additional elements that demonstrated significant variation included age, insurance status, race, Hispanic ethnicity, income, and education. TTI did not vary by comorbidity (P = .131).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics According to TTI

| Characteristic | Median (IQR) TTI, days | No. (%) of Patients by TTI in Days | Total (N = 51,655) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-30 (n = 30,744; 60%) | 31-60 (n = 15,636; 30%) | 61-90 (n = 3,648; 7%) | > 90 (n = 1,627; 3%) | ||||

| Age, years | < .001 | ||||||

| ≤ 30 | 24 (13-38) | 177 (< 1) | 70 (< 1) | 13 (< 1) | 13 (1) | 273 | |

| 31-40 | 23 (9-40) | 799 (3) | 371 (2) | 76 (2) | 35 (2) | 1,281 | |

| 41-50 | 26 (12-42) | 4,787 (16) | 2,511 (16) | 596 (16) | 259 (16) | 8,153 | |

| 51-60 | 27 (13-42) | 8,818 (28) | 4,817 (31) | 1,214 (33) | 558 (34) | 15,407 | |

| 61-70 | 26 (13-41) | 8,377 (27) | 4,300 (28) | 996 (27) | 449 (28) | 14,122 | |

| > 70 | 24 (10-39) | 7,786 (25) | 3,567 (22) | 753 (21) | 313 (19) | 12,419 | |

| Sex | .967 | ||||||

| Male | 26 (12-41) | 23,344 (76) | 11,884 (76) | 2,765 (76) | 1,243 (76) | 39,236 | |

| Female | 26 (12-41) | 7,400 (24) | 3,752 (24) | 883 (24) | 384 (24) | 12,419 | |

| Race | < .001 | ||||||

| White | 25 (12-40) | 26,692 (87) | 13,257 (85) | 2,929 (80) | 1,266 (78) | 44,144 | |

| African American | 28 (14-47) | 3,128 (10) | 1,901 (12) | 595 (16) | 305 (19) | 5,929 | |

| Asian | 26 (12-42) | 385 (1) | 199 (1) | 56 (2) | 17 (1) | 657 | |

| Other | 26 (13-41) | 539 (2) | 279 (2) | 68 (2) | 39 (2) | 925 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | < .001 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 26 (12-41) | 26,805 (87) | 13,638 (87) | 3,202 (88) | 1,378 (85) | 45,023 | |

| Hispanic | 29 (13-49) | 964 (3) | 595 (4) | 178 (5) | 123 (7) | 1,860 | |

| Other | 24 (12-39) | 2,975 (10) | 1,403 (9) | 268 (7) | 126 (8) | 4,772 | |

| Insurance status | < .001 | ||||||

| Private insurance | 25 (12-40) | 13,262 (43) | 6,686 (43) | 1,423 (39) | 568 (35) | 21,939 | |

| Medicare | 25 (11-39) | 12,232 (40) | 5,659 (36) | 1,214 (33) | 574 (35) | 19,679 | |

| Uninsured | 28 (14-45) | 1,427 (5) | 863 (6) | 245 (7) | 112 (7) | 2,647 | |

| Medicaid | 29 (15-49) | 2,234 (7) | 1,420 (9) | 454 (12) | 236 (15) | 4,344 | |

| Other government | 32 (17-49) | 427 (1) | 307 (2) | 103 (3) | 48 (3) | 885 | |

| Unknown | 28 (14-48) | 1,162 (4) | 701 (4) | 209 (6) | 89 (5) | 2161 | |

| Facility type | < .001 | ||||||

| Community | 22 (9-39) | 3,396 (11) | 1,501 (10) | 309 (9) | 158 (9) | 5,364 | |

| Comprehensive Community | 23 (10-38) | 16,049 (52) | 6,979 (45) | 1,476 (40) | 669 (41) | 25,173 | |

| Academic | 28 (15-45) | 10,719 (35) | 6,949 (44) | 1,816 (50) | 775 (48) | 20,259 | |

| Other | 20 (6-35) | 580 (2) | 207 (1) | 47 (1) | 25 (2) | 859 | |

| Distance from treatment facility, miles | < .001 | ||||||

| ≤ 10 | 26 (12-41) | 16,313 (53) | 8,043 (51) | 1,920 (53) | 888 (55) | 27,164 | |

| 10-20 | 25 (11-40) | 5,772 (19) | 2,808 (18) | 596 (16) | 253 (16) | 9,429 | |

| 21-50 | 26 (13-41) | 5,502 (18) | 2,799 (18) | 629 (17) | 247 (15) | 9,177 | |

| 51-100 | 28 (14-43) | 1,954 (6) | 1,131 (7) | 297 (8) | 140 (8) | 3,522 | |

| > 100 | 30 (12-41) | 1,203 (4) | 855 (6) | 206 (6) | 99 (6) | 2,363 | |

| Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score | .131 | ||||||

| 0 | 26 (13-41) | 25,416 (83) | 13,038 (83) | 3,051 (84) | 1321 (81) | 4,2826 | |

| 1 | 25 (12-41) | 4,199 (14) | 2,043 (13) | 469 (13) | 249 (15) | 6,960 | |

| ≥ 2 | 24 (12-40) | 1,129 (3) | 555 (4) | 128 (3) | 57 (4) | 1,869 | |

| Cancer primary site | < .001 | ||||||

| Oral tongue | 28 (14-44) | 8,325 (27) | 4,896 (31) | 1,236 (34) | 554 (34) | 15,011 | |

| Oropharynx, tonsil | 26 (9-41) | 5,528 (18) | 2,735 (18) | 660 (18) | 269 (17) | 9,192 | |

| Oropharynx, nontonsil | 30 (15-44) | 1,172 (4) | 737 (5) | 209 (6) | 77 (4) | 2,195 | |

| Larynx | 23 (9-38) | 13,743 (45) | 5,940 (38) | 1,217 (33) | 580 (36) | 21,480 | |

| Hypopharynx | 29 (18-45) | 1,976 (6) | 1,328 (8) | 326 (9) | 147 (9) | 3,777 | |

| Overall AJCC stage group | < .001 | ||||||

| I | 20 (0-34) | 8,855 (29) | 2,943 (19) | 539 (15) | 300 (19) | 12,637 | |

| II | 26 (12-39) | 4,950 (16) | 2,470 (16) | 479 (13) | 193 (12) | 8,092 | |

| III | 27 (14-42) | 6,029 (20) | 3,529 (22) | 884 (24) | 349 (21) | 10,791 | |

| IV | 28 (15-45) | 10,910 (35) | 6,694 (43) | 1,746 (48) | 785 (48) | 20,135 | |

| Treatment | < .001 | ||||||

| Surgery alone | 17 (0-34) | 6,858 (22) | 2,125 (14) | 442 (12) | 244 (15) | 9,669 | |

| RT alone | 31 (21-45) | 5,929 (19) | 4,402 (28) | 1,005 (28) | 515 (32) | 11,851 | |

| CRT | 34 (22-49) | 6,607 (21) | 6,640 (42) | 1,689 (46) | 670 (41) | 15,606 | |

| Adjuvant RT | 8 (0-26) | 7,069 (23) | 1,366 (9) | 267 (7) | 119 (7) | 8,821 | |

| Adjuvant CRT | 13 (0-27) | 3,552 (12) | 694 (4) | 151 (4) | 42 (2) | 4,439 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 14 (0-31) | 174 (1) | 42 (< 1) | 12 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 233 | |

| Preoperative RT | 30 (18-43) | 114 (< 1) | 85 (< 1) | 17 (< 1) | 9 (< 1) | 225 | |

| Preoperative CRT | 29 (18-43) | 381 (1) | 264 (1) | 62 (2) | 21 (1) | 728 | |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 18 (10-34) | 60 (< 1) | 18 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 83 | |

| Treatment year | < .001 | ||||||

| 2003 | 25 (12-40) | 10,639 (35) | 4,870 (31) | 1,186 (33) | 564 (35) | 17,259 | |

| 2004 | 26 (13-41) | 10,108 (33) | 5,314 (34) | 1,177 (32) | 489 (30) | 17,088 | |

| 2005 | 27 (13-42) | 9,997 (32) | 5,452 (35) | 1,285 (35) | 574 (35) | 17,308 | |

| Transition to academic facility | < .001 | ||||||

| Yes | 34 (21-51) | 4,123 (13) | 3,932 (25) | 1,147 (31) | 487 (30) | 9,689 | |

| No | 24 (10-38) | 26,621 (87) | 11,704 (75) | 2,501 (69) | 1,140 (70) | 41,966 | |

| Zip-code level education, % | < .001 | ||||||

| ≥ 29 | 27 (13-43) | 5,534 (18) | 3,015 (19) | 797 (22) | 420 (26) | 9,766 | |

| 20-28.9 | 26 (13-41) | 7,311 (24) | 3,794 (24) | 891 (24) | 418 (26) | 12,414 | |

| 14-19.9 | 26 (12-41) | 7,065 (23) | 3,558 (23) | 776 (21) | 337 (21) | 11,736 | |

| < 14 | 25 (12-40) | 9,127 (30) | 4,459 (29) | 982 (27) | 359 (22) | 14,927 | |

| Unknown | 24 (11-41) | 1,707 (5) | 810 (5) | 202 (6) | 93 (5) | 2,812 | |

| Zip-code level income, $ | < .001 | ||||||

| < 30,000 | 26 (13-43) | 4,782 (16) | 2,586 (17) | 670 (18) | 332 (20) | 8,370 | |

| 30,000-35,000 | 26 (13-41) | 5,867 (19) | 2,967 (19) | 627 (17) | 345 (21) | 9,806 | |

| 35,000-45,999 | 26 (12-41) | 8,398 (27) | 4,152 (26) | 971 (27) | 411 (25) | 13,932 | |

| ≥ 46,000 | 26 (12-41) | 9,992 (33) | 5,121 (33) | 1,178 (32) | 446 (28) | 16,737 | |

| Unknown | 24 (12-41) | 1,705 (5) | 810 (5) | 202 (6) | 93 (6) | 2,810 | |

NOTE. Characteristics were compared by using the χ2 test. All covariates were analyzed as categoric variables.

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CRT, chemoradiation; RT, radiation therapy; TTI, time to initiation.

The TTI distribution for 274,630 patients with HNSCC treated from 1998 through 2011 revealed that 11.4% of all patients and 20% of those who received CRT at academic facilities (n = 6,340) had TTI of greater than 60 days. In 2011, the median TTI for treatment with CRT at academic facilities was 42 days.

Increasing TTI and Survival

Table 2 reports Cox proportional hazard model results. After analysis was adjusted for all measured factors, a TTI of 61 to 90 days (hazard ratio [HR], 1.13; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.19) and of greater than 90 days (HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.21 to 1.38) significantly predicted higher risk of death compared with a TTI of 0 to 30 days, whereas a TTI of 31 to 60 days did not. After TTI was established as an independent risk factor for mortality via the Cox model, TTI thresholds to predict the largest differences in OS were identified by using RPA. RPA was performed on a randomly selected training set that consisted of 50% (n = 25,864 patients) of the survival cohort partitioned according to TTI. The optimal nonzero threshold in the training set was 67 days or fewer versus greater than 67 days (median OS, 70 months v 44 months; P < .001), which was maintained in the validation set (n = 25,791) for TTI of 67 days or fewer versus greater than 67 days (median OS, 71 months v 49 months; P < .001).

Table 2.

Multivariable Analysis With Cox Proportional Hazard Model Adjusted for Covariates to Estimate the Risk of Overall Mortality

| Covariate | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Time to treatment initiation, days | < .001 | |

| 0-30 | Reference | |

| 31-60 | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.02) | .584 |

| 61-90 | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.13) | .001 |

| ≥ 91 | 1.23 (1.15 to 1.32) | < .001 |

| Age, years | < .001 | |

| ≤ 30 | 0.37 (0.29 to 0.47) | < .001 |

| 31-40 | 0.36 (0.33 to 0.41) | < .001 |

| 41-50 | 0.45 (0.43 to 0.47) | < .001 |

| 51-60 | 0.53 (0.51 to 0.55) | < .001 |

| 61-70 | 0.65 (0.62 to 0.67) | < .001 |

| > 70 | Reference | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) | .448 |

| Female | Reference | |

| Race | < .001 | |

| White | Reference | |

| African American | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.18) | < .001 |

| Asian | 0.87 (0.77 to 0.99) | .025 |

| Other | 0.87 (0.79 to 0.97) | .009 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | < .001 | |

| Non-Hispanic | Reference | |

| Hispanic | 0.87 (0.81 to 0.94) | < .001 |

| Other | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.04) | .876 |

| Insurance status | < .001 | |

| Private insurance | Reference | |

| Medicare | 1.47 (1.42 to 1.52) | < .001 |

| Medicaid | 1.86 (1.78 to 1.95) | < .001 |

| Uninsured | 1.58 (1.49 to 1.67) | < .001 |

| Other government | 1.57 (1.43 to 1.72) | < .001 |

| Facility type | .011 | |

| Community | Reference | |

| Comprehensive community | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.00) | .038 |

| Academic | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.01) | .128 |

| Other | 1.15 (1.01 to 1.31) | .044 |

| Transition to academic facility | < .001 | |

| Yes | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.95) | < .001 |

| No | Reference | |

| Cancer primary site | < .001 | |

| Oropharynx, tonsil | Reference | |

| Oropharynx, nontonsil | 1.74 (1.64 to 1.86) | < .001 |

| Oral tongue | 1.39 (1.33 to 1.39) | < .001 |

| Larynx | 1.37 (1.32 to 1.43) | < .001 |

| Hypopharynx | 2.04 (1.94 to 2.15) | < .001 |

| Overall AJCC stage group | < .001 | |

| I | Reference | |

| II | 1.61 (1.59 to 1.64) | < .001 |

| II | 1.97 (1.95 to 1.99) | < .001 |

| IV | 2.63 (2.61 to 2.64) | < .001 |

| Treatment | < .001 | |

| Surgery alone | Reference | |

| RT alone | 1.19 (1.14 to 1.23) | < .001 |

| CRT | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.98) | .001 |

| Adjuvant RT | 0.83 (0.78 to 0.87) | < .001 |

| Adjuvant CRT | 0.75 (0.71 to 0.80) | < .001 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.55) | .001 |

| Preoperative RT | 1.34 (1.13 to 1.58) | .001 |

| Preoperative CRT | 0.94 (0.85 to 1.05) | .277 |

| Induction chemotherapy | 1.25 (0.93 to 1.68) | .144 |

| Treatment year | .432 | |

| 2003 | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) | .203 |

| 2004 | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) | .636 |

| 2005 | Reference | |

| Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score | < .001 | |

| 0 | Reference | |

| 1 | 1.34 (1.29 to 1.38) | < .001 |

| ≥ 2 | 1.76 (1.66 to 1.85) | < .001 |

| Zip-code level education, % | < .001 | |

| ≥ 29 | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.20) | < .001 |

| 20-28.9 | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.14) | < .001 |

| 14-19.9 | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09) | < .001 |

| < 14 | Reference | |

| Unknown | 1.74 (0.24 to 12.36) | .581 |

| Zip-code level income, $ | < .001 | |

| < 30,000 | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.20) | < .001 |

| 30,000-35,000 | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.15) | < .001 |

| 35,000-45,999 | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09) | .018 |

| ≥ 46,000 | Reference | |

| Unknown | 0.62 (0.09 to 4.44) | .636 |

| Distance from treatment facility, miles | < .001 | |

| ≤ 10 | Reference | |

| 11-20 | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.98) | .004 |

| 21-50 | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.96) | < .001 |

| 51-100 | 0.87 (0.83 to 0.92) | < .001 |

| > 100 | 0.78 (0.73 to 0.84) | < .001 |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CRT, chemoradiation; RT, radiation therapy.

One thousand repeated RPA simulations demonstrated that TTI partitioning was bimodal; greater than 96% of partitions identified two optimal TTI thresholds with ranges of 46 to 52 days and 62 to 67 days. As a sensitivity analysis to investigate our thresholds, we entered TTI into the full Cox regression by using restricted cubic splines to allow for a nonlinear relationship between TTI and mortality.14 This model estimated the risk of death according to TTI as a continuous variable and confirmed that this risk rises substantially after 67 days; the risk was lowest at 30 days (Fig 2). With these RPA thresholds, median OS for TTI of 46 to 52 days or fewer versus 53 to 67 days versus greater than 67 days was 71.9 months (95% CI, 70.3 to 73.5 months) versus 61 months (95% CI, 57 to 66.1 months) versus 46.6 months (42.8 to 50.7 months), respectively (P < .001). Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS according to TTI thresholds are shown in Fig 3. In 2011, 9.6% of all patients had TTI of greater than 67 days, 25% had TTI of greater than 46 days; 29.1% of patients treated at academic centers had a TTI of greater than 46 days. Of patients who received primary CRT at academic centers, 40% had a TTI of greater than 46 days.

Fig 2.

Adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of overall mortality according to time to treatment initiation (TTI) as a continuous variable by using restricted cubic splines with seven knots. The reference equals 1 at a TTI of 0 days. The restricted cubic spline allows for a nonlinear relationship of TTI with the log HR of mortality, estimated from the full Cox regression model adjusted for all covariates. The knots define change points where the cubic function can change. We found that the HR of death with respect to a TTI of zero decreased to a HR of less than 1 and then crossed the HR equivalent to 1 close to day 67, which was the cut point found in the recursive partitioning analysis . With a TTI greater than 67, the HR increased substantially.

Fig 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival (OS) according to time to treatment initiation (TTI); P value is shown for the comparison by using the log-rank test.

Interaction Effects of TTI With Other Covariates

By using a Cox regression with prespecified TTI groups, interaction effects were examined for stage (categorized as stage I to II or III to IV), care transitions, treatment modality (surgery, RT, or CRT), primary site, and facility type. Significant interaction was found with stage (P < .001), primary site (P < .001), and treatment modality (P = .0019), but not with transitions (P = .73) or facility type (P = .76). The final subgroup effects model (Fig 4) therefore tested effect of TTI with stage, primary site, and treatment modality. Each HR represents the combined effect of a covariate and TTI compared with TTI less than 30 days within each subgroup. (Appendix Table A1, online only). Fig 4A demonstrates that the effect of TTI on mortality risk is more pronounced in early-stage (ie, stage I to II) disease than advanced (ie, stage III to IV) disease. For a given TTI interval, treatment with primary RT and surgery were associated with increased mortality risk compared with treatment with definitive CRT (Fig 4B). Patients with oropharyngeal tumors had increased mortality risk compared with oral tongue and larynx/hypopharynx tumors (Fig 4C).

Fig 4.

Subgroup effects derived from interaction testing between covariates and time to treatment initiation (TTI). Each hazard ratio (HR) represents the combined effect of a covariate and TTI compared with a TTI of 30 days or fewer within each subgroup (reference, TTI ≤ 30 days; HR, 1). Only covariates identified with significant interactions were added separately to full models; significant interactions included stage (I to II and III to IV), primary tumor site (oral tongue, larynx/hypopharynx, and oropharynx), and treatment modality (surgery alone, radiation therapy [RT], or chemoradiation [CRT]). HR for overall mortality according to TTI varied by (A) stage, (B) primary site, and (C) treatment modality.

Other Factors That Affect Overall Survival

Treatment at academic facilities and comprehensive community centers was associated with improved OS compared with community hospitals (HR, 0.97 [95% CI, 0.92 to 1.01] and 0.96 [95% CI, 0.92 to 0.99], respectively; Table 2). Care transitions were associated with improved OS (P < .001). The respective unadjusted 2- and 5-year OS rates according to facility type were as follows: community, 70.4% (95% CI, 69.1% to 71.5%) and 51.6% (95% CI, 50.2% to 52.9%); comprehensive community, 72.1% (95% CI, 71.6% to 72.7%) and 54.7% (95% CI, 54.1% to 55.4%); academic, 71.7% (95% CI, 71.1% to 72.3%) and 55.5% (95% CI, 54.8% to 56.2%); and other facilities, 66.7% (95% CI, 62.0% to 70.0%) and 48.4% (95% CI, 42.7% to 53.8%; log-rank P < .001; Appendix Fig A1).

Patients with tonsil cancer had significantly better OS than patients with cancer other sites (Table 2). Treatment with comparatively rare treatment regimens (adjuvant chemotherapy, preoperative RT, and induction chemotherapy) demonstrated poor survival compared with surgery alone (Table 2). Additional predictors of OS listed in Table 2 included insurance, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education and income levels, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score, and an orderly progression in risk from stage I to stage IV disease.

DISCUSSION

Increasing TTI is an insidious phenomenon, caused in large part by the pursuit of improved care.1 Advances in pretreatment evaluations,3,15 therapy16,17 and referral to high-volume centers18-20 improve outcome but increase TTI. This analysis of greater than 50,000 patients, with comorbidity assessments, establishes a consistent relationship between prolonged TTI as an independent predictor of worse mortality that is most consistent beyond 60 days. This analysis also identifies two benchmarks for detrimental effects of increasing TTI: 62 to 67 days and 46 to 52 days. TTI of 67 days was the optimal threshold on the initial RPA and was confirmed via simulation, which provides strong evidence that TTI greater than 67 days is too long and should be considered unacceptable. Treatment must begin more expeditiously. An additional TTI threshold of 46 to 52 days combined to appear on 96% of the random repeat simulations. Shortening the package time of cancer therapy has long been valued by head and neck oncologists.21 Reduction of TTI to fewer than 46 days could similarly affect survival.

Current State of TTI According to Proposed Benchmarks

Although a TTI of greater than 2 months may seem long to any oncologist, 9.6% of all patients in 2011 had TTI of greater than 67 days. By contrast, TTI greater than 46 days is of more concern, because 25% of patients treated in 2011 had TTI of greater than 46 days, which indicates that such a delay is common. An even higher percentage (29%) of patients treated at academic facilities (a situation associated with increased TTI) in 2011 had TTI of greater than 46 days, likely because of care transitions that disproportionately affect academic centers (48% of patients treated at academic facilities transitioned from another facility). Trends suggest that in 2015 more patients will be treated at academic centers and their resultant TTI will be even higher.1 In 2011, 40% of patients treated with CRT at academic centers had TTI of greater than 46 days. The current analysis suggests that increasing TTI beyond the threshold established in this monograph alters HNSCC survival and represents a public health issue.

Precedent exists to shorten TTI. The Danish health system reported TTI for HNSCC greater than that in the United States. A bundled multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment was introduced to remedy prolonged TTI.22-25 Such an endeavor requires considerable coordination among providers, and it mandates expedited appointments for patients with a new cancer diagnosis. Recently piloted programs offering next-day appointments with cancer specialists address this reversible predictor of mortality26 and may partially alleviate increasing TTI. Without such reforms, it is conceivable that outcomes will continue to worsen because of prolonged TTI.

Early-Stage Disease

Interaction testing demonstrated that mortality risk according to TTI was greater for patients with stage I to II disease than for those with stage III to IV disease. Patients with stage I to II disease have no lymph node involvement, but lymph node dissemination advances a patient to at least stage III. The development of nodal disease is a significant prognostic factor27-29 that persists in the human papillomavirus era.30,31 The demonstrable impact of increasing TTI on early-stage tumors may be associated with stage progression, a risk factor for mortality from HNSCC.7,8,32 Current practice patterns potentially exacerbate this issue; surgical wait times are generally longest for patients with early-stage disease,6,33-35 and priority is given to patients with advanced-stage disease in an effort to commence therapy before their tumors become formally unresectable or before they develop distant metastases. It is unclear whether such practice patterns actually benefit patients with advanced-stage disease, but this report suggests that the practice may adversely affect patients with early-stage disease.

Benefits of Specialization

The relative rarity of HNSCC36 and complexity of therapy encourages centralization of care at high volume centers.37 Care transitions to academic facilities are rising1 and are accompanied by an inherent increase in TTI, introducing immediate conflict with the survival findings of this analysis. However, the data should not be misinterpreted to suggest that increased TTI to pursue a second opinion is detrimental—the improved survival at academic and comprehensive facilities suggests the opposite. It appears that treatment at high volume facilities mitigates some portion of mortality risk of prolonged TTI, but transitions should be structured to avoid detrimental delays.

Patient Delay and Professional Delay

Longer TTI has two components: patient delay (typically defined as the time from the patient’s first awareness of symptoms to first consultation with a health professional) and professional delay (time from the patient’s first consultation through final histologic diagnosis and evaluation to treatment). Addressing unique aspects of patient delay may involve not just primary care physicians, otolaryngologists, and oncologists but also the help of psychiatrists, addiction specialists, and counseling and social work specialists.38-41 Professional delay includes TTI as defined in this study and delay in diagnosis itself, which is influenced by many factors, including symptoms, location, and size of primary tumor, stage, and comorbidity.42-45 A meta-analysis to assess the effect of patient delay (relative risk of mortality, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.21 to 1.94) or professional delay (relative risk of mortality, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.78) found that referral delay (time between first symptom and date of referral letter to secondary specialist provider) was associated with a three-fold mortality risk.46 The findings are limited by the varied definitions of delay and heterogeneous populations, but they demonstrate that many reasons for prolonged times affect outcome.

Several other variables demonstrated statistically significant associations with mortality risk, including race, Hispanic ethnicity, distance from treatment facility, and income and education levels. The extent and magnitude of these effects related to their clinical relevance have been previously investigated and act as potential barriers to care.47-49 Although the authors acknowledge the importance of these factors, the level of detail required for additional investigation of these factors is beyond the scope of the current analysis.

Additional investigation into the effect of delay on cancer-specific outcomes is warranted, because this end point is not recorded in the NCDB. The NCDB cannot account for diagnostic delay (measuring only time after diagnosis). It is possible that both patient and professional factors similarly extend TTI, but ascribing the proportion of increase in TTI discreetly to either is beyond the capability of the NCDB. Although rigorous internal validation was used to test our proposed benchmarks for TTI, additional validation with external data should be undertaken. Additional limitations include those surrounding use of tumor registry data: unmeasured confounding, selection bias, incomplete data, and coding errors. The data presented here are restricted to hospitals that report to the NCDB and may not reflect practice patterns in outpatient community facilities, because these occurrences are not reported to this database.

In conclusion, through the use of a large national tumor registry, this study demonstrated that patients with TTI of greater than 46 to 52 days have increased risk of mortality that is greatest for patients with early-stage disease. Risk associated with increasing TTI currently affects a substantial percentage of patients with HNSCC (25%) in the United States. These results suggest that efforts should be made to ensure that patients with HNSCC initiate appropriate treatment in a timely manner to avoid potentially detrimental deferral of treatment. Patients undergoing a transition in care may require greater coordination to reduce TTI.

Appendix

Table A1.

Subgroup Interaction Effects Model

| Covariate | Combined Effect Subgroup Model According to TTI, Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 30 d | 31-60 d | 61-90 d | > 90 d | |

| Overall AJCC stage group | ||||

| I-II | Reference | 1.17 (1.12 to 1.23) | 1.54 (1.41 to 1.68) | 1.52 (1.33 to 1.72) |

| III-IV | Reference | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.07) | 1..08 (1.02 to 1.14) | 1.29 (1.20 to 1.40) |

| Primary tumor site | ||||

| Oral tongue | Reference | 0.88 (0.84 to 0.93) | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.04) | 1.09 (0.98 to 1.23) |

| Larynx/hypopharynx | Reference | 1.04 (1.01 to 1.09) | 1.16 (1.09 to 1.24) | 1.35 (1.23 to 1.48) |

| Oropharynx | Reference | 1.39 (1.32 to 1.46) | 1.24 (1.12 to 1.38) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.56) |

| Treatment modality | ||||

| CRT | Reference | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.97) | 0.94 (0.88 to 1.01) | 1.22 (1.11 to 1.35) |

| RT | Reference | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.13) | 1.28 (1.17 to 1.40) | 1.30 (1.16 to 1.46) |

| Surgery | Reference | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.12) | 1.25 (1.14 to 1.37) | 1.24 (1.08 to 1.43) |

NOTE. Subgroup effects derived from interaction testing between covariates and time to treatment initiation (TTI). Each hazard ratio represents the combined effect of a covariate and TTI compared with TTI ≤ 30 days within each subgroup. Only covariates identified with significant interaction were included in the combined effects model, which include stage (I-II or III-IV), primary tumor site (tongue, larynx/hypopharynx, or oropharynx), and treatment modality (chemoradiation [CRT], radiation [RT], or surgery alone).

Abbreviation: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Fig A1.

Overall survival by facility type. Comm, community; Comp comm, comprehensive community.

Footnotes

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Colin T. Murphy, Thomas J. Galloway, John A. Ridge

Collection and assembly of data: Colin T. Murphy, Thomas J. Galloway, Elizabeth A. Handorf

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Survival Impact of Increasing Time to Treatment Initiation for Patients With Head and Neck Cancer in the United States

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Colin T. Murphy

No relationship to disclose

Thomas J. Galloway

Consulting or Advisory Role: AMAG Pharmaceuticals

Elizabeth A. Handorf

Research Funding: Pfizer

Brian J. Egleston

Consulting or Advisory Role: Teva

Research Funding: Janssen Infectious Diseases - Diagnostics BVBA

Lora S. Wang

No relationship to disclose

Ranee Mehra

Employment: GlaxoSmithKline (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squib, Novartis

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech, Novartis

Douglas B. Flieder

No relationship to disclose

John A. Ridge

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Murphy CT, Galloway TJ, Handorf EA, et al. Increasing time to treatment initiation for head and neck cancer: An analysis of the National Cancer Database. Cancer. 2015;121:1204–1213. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sher DJ, Neville BA, Chen AB, et al. Predictors of IMRT and conformal radiotherapy use in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A SEER-Medicare analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:e197–e206. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillner BE, Tosteson AN, Song Y, et al. Growth in the use of PET for six cancer types after coverage by Medicare: Additive or replacement. J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith BD, Haffty BG, Wilson LD, et al. The future of radiation oncology in the United States from 2010 to 2020: Will supply keep pace with demand. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5160–5165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-A-New-Health-System-for-the-21st-Century.aspx.

- 6.Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Tomlinson JS, et al. Wait times for cancer surgery in the United States: Trends and predictors of delays. Ann Surg. 2011;253:779–785. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318211cc0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waaijer A, Terhaard CHJ, Dehnad H, et al. Waiting times for radiotherapy: consequences of volume increase for the TCP in oropharyngeal carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2003;66:271–276. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(03)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen AR, Nellemann HM, Overgaard J. Tumor progression in waiting time for radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2007;84:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pulte D, Brenner H. Changes in survival in head and neck cancers in the late 20th and early 21st century: A period analysis. Oncologist. 2010;15:994–1001. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, et al. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:683–690. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9747-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mell LK, Dignam JJ, Salama JK, et al. Predictors of competing mortality in advanced head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:15–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schemper M, Smith TL. A note on quantifying follow-up in studies of failure time. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:343–346. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(96)00075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeBlanc M, Crowley J. Relative risk trees for censored survival data. Biometrics. 1992;48:411–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrell FE. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lonneux M, Hamoir M, Reychler H, et al. Positron emission tomography with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose improves staging and patient management in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A multicenter prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1190–1195. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.6298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pignon JP, Bourhis J, Domenge C, et al. Chemotherapy added to locoregional treatment for head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: Three meta-analyses of updated individual data—MACH-NC collaborative group.meta-analysis of chemotherapy on head and neck cancer. Lancet. 2000;355:949–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nutting CM, Morden JP, Harrington KJ, et al. Parotid-sparing intensity modulated versus conventional radiotherapy in head and neck cancer (PARSPORT): A phase 3 multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:127–136. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70290-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen AY, Fedewa S, Pavluck A, et al. Improved survival is associated with treatment at high-volume teaching facilities for patients with advanced stage laryngeal cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:4744–4752. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen AY, Pavluck A, Halpern M, et al. Impact of treating facilities’ volume on survival for early-stage laryngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2009;31:1137–1143. doi: 10.1002/hed.21072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EVA, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ang KK, Trotti A, Brown BW, et al. Randomized trial addressing risk features and time factors of surgery plus radiotherapy in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:571–578. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01690-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Primdahl H, Nielsen AL, Larsen S, et al. Changes from 1992 to 2002 in the pretreatment delay for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of larynx or pharynx: A Danish nationwide survey from DAHANCA. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:156–161. doi: 10.1080/02841860500423948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toustrup K, Lambertsen K, Birke-Sørensen H, et al. Reduction in waiting time for diagnosis and treatment of head and neck cancer: A fast track study. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:636–641. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.551139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorensen JR, Johansen J, Gano L, et al. A “package solution” fast track program can reduce the diagnostic waiting time in head and neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:1163–1170. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2584-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyhne NM, Christensen A, Alanin MC, et al. Waiting times for diagnosis and treatment of head and neck cancer in Denmark in 2010 compared to 1992 and 2002. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1627–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox Chase Cancer Center: Rapid Access Appointments https://www.fccc.edu/myFoxChase/patients/enrollment/index.html.

- 27.Merino OR, Lindberg RD, Fletcher GH. An analysis of distant metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of the upper respiratory and digestive tracts. Cancer. 1977;40:145–151. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197707)40:1<145::aid-cncr2820400124>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leemans CR, Tiwari R, Nauta JJ, et al. Regional lymph node involvement and its significance in the development of distant metastases in head and neck carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:452–456. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930115)71:2<452::aid-cncr2820710228>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leemans CR, Tiwari R, Nauta JJ, et al. Recurrence at the primary site in head and neck cancer and the significance of neck lymph node metastases as a prognostic factor. Cancer. 1994;73:187–190. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940101)73:1<187::aid-cncr2820730132>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Sullivan B, Huang SH, Siu LL, et al. Deintensification candidate subgroups in human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer according to minimal risk of distant metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:543–550. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kowalski LP, Carvalho AL. Influence of time delay and clinical upstaging in the prognosis of head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2001;37:94–98. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crawford SC, Davis JA, Siddiqui NA, et al. The waiting time paradox: Population-based retrospective study of treatment delay and survival of women with endometrial cancer in Scotland. BMJ. 2002;325:196. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Comber H, Cronin DP, Deady S, et al. Delays in treatment in the cancer services: Impact on cancer stage and survival. Ir Med J. 2005;98:238–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wildt J, Bundgaard T, Bentzen SM. Delay in the diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1995;20:21–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1995.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wuthrick EJ, Zhang Q, Machtay M, et al. Institutional clinical trial accrual volume and survival of patients with head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:156–164. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tromp DM, Brouha XDR, Hordijk G-J, et al. Patient factors associated with delay in primary care among patients with head and neck carcinoma: A case-series analysis. Fam Pract. 2005;22:554–559. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brouha X, Tromp D, Hordijk G-J, et al. Role of alcohol and smoking in diagnostic delay of head and neck cancer patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125:552–556. doi: 10.1080/00016480510028456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brouha XDR, Tromp DM, Hordijk G-J, et al. Oral and pharyngeal cancer: analysis of patient delay at different tumor stages. Head Neck. 2005;27:939–945. doi: 10.1002/hed.20270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Christophe V, Leroy T, Seillier M, et al. Determinants of patient delay in doctor consultation in head and neck cancers (Protocol DEREDIA) BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005286. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carvalho AL, Pintos J, Schlecht NF, et al. Predictive factors for diagnosis of advanced-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:313–318. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teppo H, Alho OP. Comorbidity and diagnostic delay in cancer of the larynx, tongue and pharynx. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:692–695. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teppo H, Koivunen P, Hyrynkangas K, et al. Diagnostic delays in laryngeal carcinoma: Professional diagnostic delay is a strong independent predictor of survival. Head Neck. 2003;25:389–394. doi: 10.1002/hed.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brouha XDR, Tromp DM, Koole R, et al. Professional delay in head and neck cancer patients: Analysis of the diagnostic pathway. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:551–556. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seoane J, Takkouche B, Varela-Centelles P, et al. Impact of delay in diagnosis on survival to head and neck carcinomas: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2012;37:99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2012.02464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albano JD, Ward E, Jemal A, et al. Cancer mortality in the United States by education level and race. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1384–1394. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shavers VL, Harlan LC, Winn D, et al. Racial/ethnic patterns of care for cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, sinuses, and salivary glands. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:25–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1022255800411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]