Abstract

Replication of the hepatitis C viral genome is catalyzed by the NS5B (nonstructural protein 5B) RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, which is a major target of antiviral drugs currently in the clinic. Prior studies established that initiation of RNA replication could be facilitated by starting with a dinucleotide (pGG). Here we establish conditions for efficient initiation from GTP to form the dinucleotide and subsequent intermediates leading to highly processive elongation, and we examined the effects of four classes of nonnucleoside inhibitors on each step of the reaction. We show that palm site inhibitors block initiation starting from GTP but not when starting from pGG. In addition we show that nonnucleoside inhibitors binding to thumb site-2 (NNI2) lead to the accumulation of abortive intermediates three-five nucleotides in length. Our kinetic analysis shows that NNI2 do not significantly block initiation or elongation of RNA synthesis; rather, they block the transition from initiation to elongation, which is thought to proceed with significant structural rearrangement of the enzyme-RNA complex including displacement of the β-loop from the active site. Direct measurement in single turnover kinetic studies show that pyrophosphate release is faster than the chemistry step, which appears to be rate-limiting during processive synthesis. These results reveal important new details to define the steps involved in initiation and elongation during viral RNA replication, establish the allosteric mechanisms by which NNI2 inhibitors act, and point the way to the design of more effective allosteric inhibitors that exploit this new information.

Keywords: computer modeling, enzyme kinetics, hepatitis C virus (HCV), inhibition mechanism, viral polymerase, viral replication, NS5B, RNA initiation, non nucleoside inhibitors

Introduction

Approximately 3% of the world's population is infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV),2 including four-five million people in the United States, and chronic HCV infections lead to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (1, 2). The hepatitis C viral genome is replicated by NS5B, a virally encoded RNA-dependent RNA polymerase requiring de novo initiation of RNA synthesis. Antivirals acting directly against viral proteins including NS5B have been developed recently that have dramatically improved the prognosis for treatment (3–5). However, despite these advances, the biochemical mechanisms of action of drugs currently on the market are poorly understood, and very little is known about the kinetics and mechanism of initiation and elongation governing RNA polymerization. In this and the companion paper (6), we begin to address these deficiencies.

Replication proceeds through three distinct phases: 1) initiation, in which the 3′-end of the RNA acts as a template to direct the formation of the initial dinucleotide followed by the addition of two-three more nucleotides; 2) transition, in which the polymerase dramatically changes structure to switch from the initiation to elongation mode; 3) elongation, in which the polymerase catalyzes rapid and highly processive synthesis (7). A β-loop structure projecting from the “thumb” domain is thought to facilitate the initiation reaction but also blocks the active site, effectively preventing the binding of duplex RNA from solution (8). Accordingly, it is thought that the β-loop must swing out of the active site as the enzyme switches from initiation to elongation modes during the transition phase.

A major advance in studying the polymerization reaction was achieved in studies showing that a 1–2-h incubation of enzyme with template, a dinucleotide (pGG), and 2 of the 4 nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) led to the formation of a stalled, yet very stable elongation complex that catalyzed subsequent elongation reactions with processivity and rates expected for viral replication in vivo (7, 9). These studies enable dissection of the kinetics of polymerization during processive elongation using transient state kinetic analysis. As exemplified by studies on HIV reverse transcriptase, transient kinetic analysis allows direct measurement of the mechanisms of polymerization and modes of inhibition by both nucleoside analogs and nonnucleoside inhibitors (10–14).

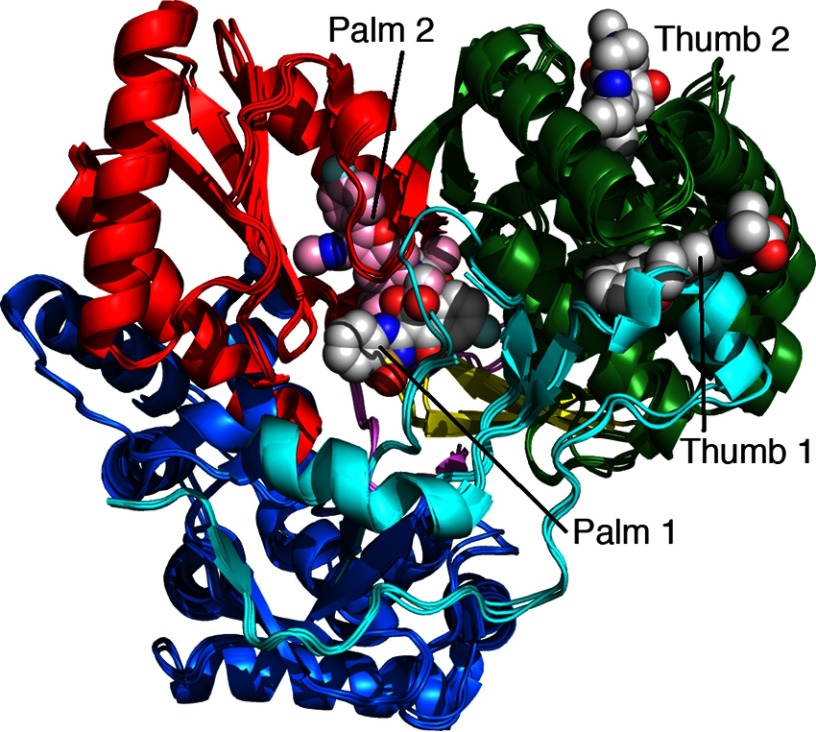

In addition to nucleoside analogs, four classes of nonnucleoside inhibitors have been discovered that bind to different sites on the NS5B polymerase as shown in Fig. 1 (15). Palm site 1 and palm site 2 inhibitors bind to residues in the palm domain, which contains the catalytic residues for polymerization, and accordingly are expected to serve as competitive inhibitors. Thumb site 1 inhibitors bind at the junction between the thumb domain and the fingers extension and appear to disrupt this crucial structural interaction. Most interesting are the thumb site 2 inhibitors, which bind to the outside surface of the thumb domain and, therefore, must act allosterically to alter polymerase dynamics.

FIGURE 1.

Binding sites for four classes of nonnucleoside inhibitors. Structures with each of the four classes of NNI bound are overlaid to illustrate the four binding sites: Palm 1 (PDB code 2giq), Palm 2 (PDB code 3fqk), Thumb 1 (PDB code 2dxs) and Thumb 2 (PDB code 3frz). Thumb I inhibitors cause an outward movement of the thumb and disorder in the fingers extension domain, which is not shown well in this overlay. Palm 1 site inhibitors interact with the palm, fingers, and thumb domains in addition to the β-loop (Leu-443-Val-454). Palm 1 and Palm 2 sites are distinguished by their distinct patterns of resistance mutations seen in replicon assays, but there is some overlap. Color-coding of the protein structure shows the fingers (blue), palm (red), thumb (green), finger extension (cyan), β-loop (yellow), and C-terminal linker (violet). Inhibitors are shown in space-filling CPK colors, but the Palm 2 inhibitor is shown in pink with CPK coloring for nitrogen, phosphorus, and oxygen.

Here we report the kinetics of the initiation, transition, and elongation reactions. We show how thumb site 2 nonnucleoside inhibitors (GS-9669, Lomibuvir and Filibuvir) do not inhibit initiation or elongation but, rather, slow the transition from initiation to elongation. In a companion paper (6) we use hydrogen/deuterium exchange kinetic analysis monitored by mass spectrometry to provide molecular details of the long range interactions caused by the binding of nonnucleoside analogs on the surface of the thumb domain (thumb site 2).

Experimental Procedures

Nucleic Acids, Chemicals, and Protein

Lomibuvir, Filibuvir, and GS-9669 used in kinetic studies were kindly provided by Gilead Sciences. The 20-mer RNA template (5′-AAUCUAUAACGAUUAUAUCC-3′) was synthesized chemically by Dharmacon (Chicago, IL). NTPs were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Tris-Cl buffers and solutions of NaCl, MgCl2, EDTA were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). N-terminal penta-His-NS5BΔ21 (con1 strain, GT1b with 21 amino acid deletion at the C terminus) was cloned, expressed, and purified as described previously (7) and dialyzed into storage buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7, 400 mm NaCl, 2 mm DTT, 10% glycerol).

Replicates

All experiments were performed at least two-three times to demonstrate that the results were reproducible.

HCV NS5B Initiation Assay

For GTP-start RNA initiation, NS5B (10 μm) alone or with various nonnucleoside inhibitors were preincubated in the buffer containing 40 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.0, 20 mm NaCl, 5 mm DTT, and 2 mm MgCl2 for 30 min at 30 °C. Primer formation was initiated by adding 1 mm GTP, 50 μm [α-32P]ATP, UTP, and ddCTP. Aliquots (5 μl) from the reaction were quenched at various times up to 4 h by mixing with 30 μl of a quench solution containing 90% formamide, 50 mm EDTA, 0.1% bromphenol blue, and 0.1% xylene cyanol. The quenched reaction samples were heat-denatured for 3 min at 95 °C and applied to a 16% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (7 m urea) for electrophoresis at 100 watts using the Bio-Rad Sequi-Gen GT system. Gels were exposed to a storage phosphor screen and imaged by the Typhoon 9400 scanner (GE Healthcare). Band intensity was quantified using ImageQuant (GE Healthcare). Product formation was calculated as the fractional intensity of each product band relative to the sum of the intensities of all bands in a particular lane. The pGG dimer start RNA initiation was performed similarly to GTP-start assay as shown in Scheme 1 and described previously (7).

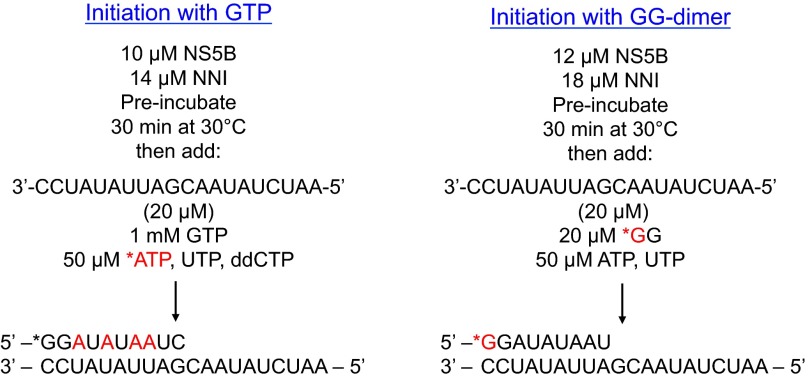

SCHEME 1.

Protocols for RNA initiation. Two protocols were used to initiate RNA synthesis as shown in the two schemes, involving starting with pGG (right) or with GTP (left). In each case the enzyme was preincubated with (or without) inhibitor, then RNA template and nucleotides were added to start the reaction.

HCV NS5B Elongation Assay

A GTP-start initiation reaction was allowed to develop for 2 h in the presence of various NNI2s to form NNI/NS5B/9-mer/20-mer elongation complex (Scheme 1). After 2 h, the reaction mixture was centrifuged, purified, and resuspended in the elongation buffer (40 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm DTT, and 2 mm MgCl2) as described previously (7). Using an RQF-3 rapid quench-flow instrument (KinTek Corp., Austin, TX), 0.2 μm NNI-bound NS5B elongation complex (final concentration after mixing) was reacted with 400 μm concentrations of all four NTPs and 4 μm NNI in the elongation buffer at 30 °C. Each reaction was quenched by mixing with the quench solution at the indicated time points as shown in Fig. 5. The fraction of each species among the products formed was determined as described in the initiation assay.

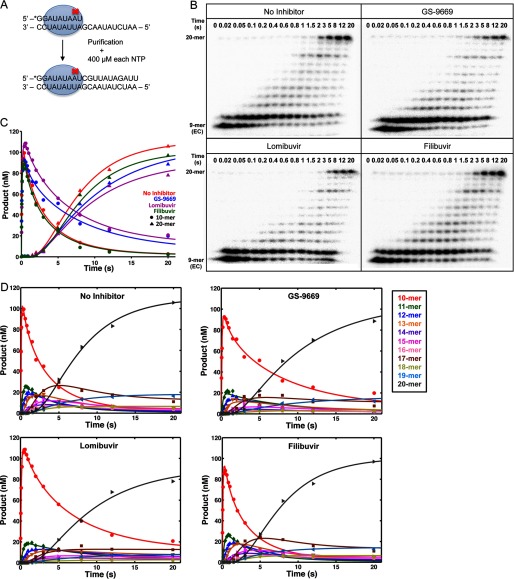

FIGURE 5.

HCV NS5B elongation in the presence of NNI2. A, a scheme depicting the experimental setup for HCV NS5B elongation assay. Through the initiation assay with GTP start, NS5B/9-mer/20-mer elongation complex was generated and isolated then reacted with 400 μm ATP, UTP, GTP, and CTP in the elongation buffer and quenched at the indicated time intervals. B, multiple nucleotide incorporation during NS5B elongation in the presence of NNIs was monitored on a PAGE gel. C, the time course of 10-nt and 20-nt products formation were global fitted to a mechanism for processive nucleotide incorporation catalyzed by NS5B using KinTek Explorer. D, the time course of multiple nucleotide incorporation from 10-nt to 20-nt by HCV NS5B in the presence of NNI2.

Measurement of Pyrophosphate Release Kinetics

200 nm NS5B/9-mer/20-mer elongation complex was obtained and preincubated with 0.6 μm yeast inorganic pyrophosphatase (PPase), 0.5 μm 7-diethylamino-3-((((2maleimidyl)ethyl)amino)carbonyl)coumarin (MDCC)-labeled phosphate-binding protein (PBP) and a “Pi MOP” consisting of 100 μm 7-methylguanosine (7-MEG), and 0.02 units/ml purine nucleoside phosphorylase in the elongation buffer (16). Then 200 μm CTP was added to the reaction mix, and the pyrophosphate (PPi) release signal after CTP incorporation was monitored by KinTek stopped-flow instrument (KinTek) at 30 °C for 1 s. The same experiment was repeated for each NNI2-bound HCV elongation complex.

The kinetics of Pi binding to MDCC-PBP was characterized by recording fluorescence signals from mixing 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, and 3.2 μm Pi with 0.5 μm PBP at 30 °C for 0.1 s using the stopped flow instrument. These data served to calibrate the kinetics of the assay and were included in the global data fitting using KinTek Explorer software (17, 18). The kinetics of PPi hydrolysis by PPase was determined by incubating 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, and 3.2 μm PPi with 0.6 μm PPase and 0.5 μm MDCC-PBP in the presence of Pi “MOP.” A fluorescence signal was measured by stopped flow instrument at 30 °C for 0.15 s.

HCV NS5B Elongation Complex Stability Assay

NNI/NS5B/9-mer/20-mer elongation complex was generated after the 2-h initiation reaction then resuspended in the elongation buffer and incubated at 30 °C for up to 44 h in the presence and absence of 0.2 mg/ml heparin. To examine the remaining activity of the elongation complex, a 10-μl aliquot of the sample was reacted with 10 μl of 100 μm CTP for 20 s and quenched by 60 μl of quench solution. The percentage of CTP incorporation was calculated from the fraction of primer that was elongated as described in the initiation assay to provide a measurement of the remaining active elongation complex.

Data Fitting and Analysis

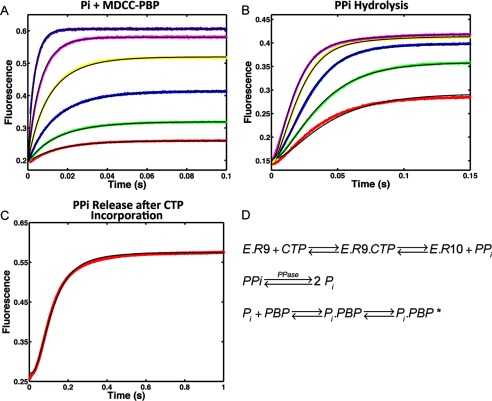

The kinetics of multiple nucleotide incorporations during NS5B initiation and elongation were fitted globally using the Kinetic Explorer (KinTek) to define the rate of each step in the polymerization reaction as described previously (17, 18). The kinetics of Pi binding to MDCC-PBP, PPi hydrolysis by PPase, and PPi release were fitted globally (see Fig. 6D) using KinTek Explorer to determine the rate constants summarized in Table 1.

FIGURE 6.

Kinetics of PPi release after CTP (10-mer) incorporation by NS5B elongation complex. A, calibration of Pi binding to MDCC labeled PBP. Reactions containing 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, and 3.2 μm Pi were reacted against 0.5 μm PBP. The fluorescence signal was monitored by stopped-flow at 30 °C for 0.1 s. B, kinetics of PPi hydrolysis by yeast inorganic PPase was determined by incubating 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, and 3.2 μm PPi with 0.6 μm PPase and 0.5 μm MDCC-PBP. After PPi was hydrolyzed by PPase into Pi and captured by PBP, the fluorescence signal was measured at 30 °C for 0.15 s. C, 200 μm CTP was introduced as the incoming nucleotide at 10-mer position for HCV elongation complex (200 nm). The PPi release signal after CTP incorporation was measured in the presence of 0.6 μm PPase and 0.5 μm MDCC-PBP at 30 °C for 1 s. The experiment was repeated for NNI2-bound HCV elongation complex. All experiments were globally fitted to Panel D using KinTek Explorer to determine rate constants summarized in Table 1. D, scheme showing the method for measuring PPi release using hydrolysis by PPase and the binding of Pi to the fluorescently labeled PBP.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters for elongation and PPi release

Rates of incorporation and pyrophosphate release were measured as described in the text. S.E. limits were derived by nonlinear regression in globally fitting each data set (18). The numbers in parentheses are the upper and lower boundaries from confidence contour analysis (17).

| Inhibitor | CTP incorporation (10-mer) | PPi release | GTP incorporation (11-mer) |

|---|---|---|---|

| s−1 | s−1 | s−1 | |

| None | 10 ± 1.8 (9.1–10.9) | 65 ± 3.0 (>27) | 1.6 ± 0.9 (1.3–2.2) |

| GS-9669 | 7.7 ± 0.8 (6.8–9.3) | 17 ± 0.5 (8.8–65.7) | 1.6 ± 0.6 (1.0–3.3) |

| Lomibuvir | 6.8 ± 0.2 (6.5–7.3) | 43 ± 1.6 (>22) | 0.8 ± 0.1 (0.6–1.1) |

| Filibuvir | 8.4 ± 0.5 (7.8–9.3) | 30 ± 0.7 (19.6–74.8) | 1.5 ± 0.2 (1.2–1.9) |

Results

Effect of GTP and NaCl Concentrations on NS5B Initiation Efficiency

Although earlier success was based upon using pGG to start the initiation reaction (7), we sought conditions to study initiation starting with GTP to more closely mimic the physiological reaction. To determine the optimum assay conditions for RNA synthesis by NS5B in vitro, we first examined how GTP concentration affects the efficiency of primer formation. The GTP-start RNA initiation assay was performed with GTP concentrations ranging from 50 to 1000 μm. Products were labeled by the incorporation of [α-32P]ATP, occurring with the formation of the trinucleotide so the kinetics of dinucleotide formation were not observed directly. As shown in Fig. 2, the results indicated that a high GTP concentration (mm) is required to allow efficient formation of nascent primers and RNA elongation product. Previously, Jin et al. (7) discovered that a reaction buffer with a low NaCl concentration provided more efficient formation of the NS5B elongation complex. Thus we performed the GTP-start assay in reaction buffer containing NaCl concentrations ranging from 20 to 150 mm. Our observations are consistent with the prior study; a reaction buffer containing 20 mm NaCl yielded the highest amount of RNA synthesis (Fig. 2). Subsequent studies use 1 mm GTP in a buffer containing 20 mm NaCl.

FIGURE 2.

Optimization of HCV NS5B initiation assay. Various concentrations of GTP ranging from 50 to 1000 μm were examined to determine the optimum for efficient primer formation (upper panel). In the presence of 500 μm GTP, reaction buffer containing 20–150 mm NaCl were assessed for initiation efficiency (lower panel). The kinetics of NS5B initiation was monitored by following the time dependence of elongation complex formation, resulting in the 10-nt product observed on a denaturing PAGE gel. HCV initiation is most efficient at high concentrations of GTP (1000 μm) and a low concentration of NaCl (20 mm).

RNA Initiation with GTP Versus pGG Dimer

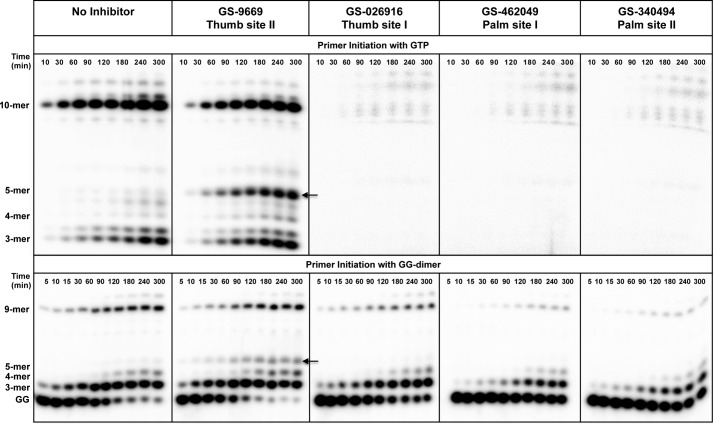

The GTP-start initiation assay is adapted from the pGG-start initiation assay developed by Jin et al. (7). We next compared the effect of four different classes of NNIs on RNA initiation using each of the two methods (GTP-start and pGG-start). As shown in Fig. 3, we observed an increase in formation of abortive intermediates (3–5 nt) in the presence of Thumb-site 2 inhibitor GS-9669 in both assays relative to when the inhibitor was absent. However, in the cases of Palm-site inhibitors GS-462049 and GS-340494 and Thumb-site 1 inhibitor GS-026916, no significant product formation was seen in assays started with GTP, although only slight inhibition was observed in the pGG-start assay. The high potency of GS-026916, GS-462049, and GS-340494 observed in RNA synthesis initiated with GTP, but not with pGG, suggests that these inhibitors may block the formation of the initial dinucleotide. Moreover, these data suggest that the GTP-start initiation assay may be more suitable for HCV inhibitor analysis, in addition to being more physiologically relevant. All subsequent studies were performed using the GTP-start conditions.

FIGURE 3.

HCV NS5B initiation with GTP versus pGG dimer in the presence of NNIs. The experimental setup for RNA initiation with either GTP or pGG dimer is depicted in Scheme 1. The time course of primer extension and elongation complex formation (10-mer for GTP start and 9-mer for pGG start) was monitored on PAGE gel. The arrow denotes the abortive intermediates (5-mer), which appear in the presence of GS-9669 in both assays. In the presence of GS-026916, GS-46029, and GS-340494, elongation complex formation was slightly inhibited in assays started with the pGG dimer, but no significant product formation was seen in assays started with GTP.

Effect of NNI2 on RNA Initiation

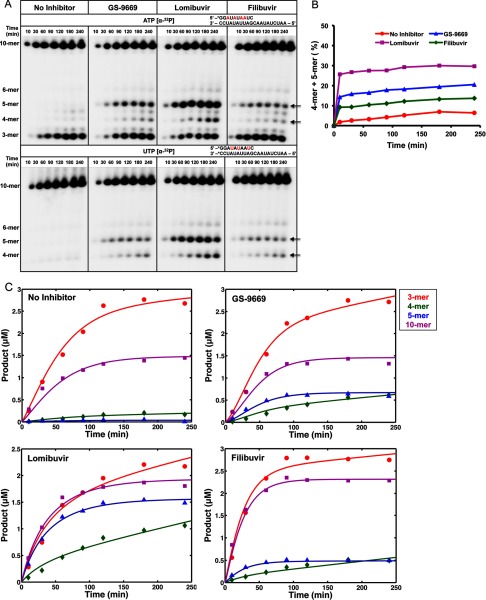

We then examined in more detail the effect of three NNI2s (GS-9669, Lomibuvir and Filibuvir) on the de novo initiation of RNA synthesis. In our assay conditions, primer formation is terminated after generating a 10-nt product due to the incorporation of the chain terminator, ddCTP. Prior studies have established that the polymerase forms a very stable elongation complex with the RNA template and newly synthesized primer under these conditions (7). We first preincubated NS5B with an excess of each NNI2 for 30 min at 30 °C and then added the RNA template and nucleotides to begin the initiation and primer extension reactions (Scheme 1). The kinetics of NS5B initiation were monitored by following the time courses for formation of each intermediate and the final stable elongation complex (10 nt), which were resolved by gel electrophoresis. A similar assay was performed using [α-32P]UTP rather than [α-32P]ATP, and the radiolabeled products from both experiments were compared with identify the intermediates (Fig. 4A). Note that it is not feasible to use [α-32P]GTP because the high concentration of GTP required for efficient initiation contributes a high background obscuring the observation of intermediates.

FIGURE 4.

HCV NS5B initiation in the presence of NNI2. A, time course of primer formation (10-mer) was monitored on denaturing PAGE gel. 10 μm NS5B was preincubated with 14 μm concentrations of each NNI2 for 30 min, and primer formation was initiated by adding 1 mm GTP and 50 μm ATP, UTP, and ddCTP and quenched at the indicated time intervals. Abortive intermediates were observed due to de novo initiation catalyzed by NS5B. The arrows denote the abortive intermediates (four and five nucleotides) formed in reactions where NNI2s were present. The initiation assay was also performed with either [α-32P]ATP or [α-32P]UTP as the radioactive probe. By comparing radiolabeled products between [α-32P]ATP (upper panel) and [α-32P]UTP (lower panel), we established the identities of different abortive intermediates. B, fraction of the abortive intermediates species (4- and 5-mer) relative to total product was plotted against reaction time. C, the amount of extended primer as well as abortive intermediates with various lengths was plotted versus time. Data were fit based on simulated model as shown in Scheme 2 using KinTek Explorer.

In Fig. 4A the arrows denote abortive intermediates that accumulate over time as the full-length primer is formed. In the absence of NNI2s the major abortive intermediate is a trimer, as described previously (7). However, in the presence of each of the NNI2s there was a significant increase in the formation of abortive intermediates 4 and 5 nucleotides in length. Similar results were obtained in assays performed using a lower concentration of NS5B (1 μm), although the initiation efficiency was not as high (data not shown). It is important to note that the abortive “intermediates” do not decrease in intensity at longer reaction times, suggesting that they accumulate in solution and do not efficiently rebind to the enzyme.

The total fraction of 4-mer and 5-mer relative to total product at each time point was plotted versus time as shown in Fig. 4B. The data indicate that during the de novo initiation phase of NS5B replication, ∼5% of the initiated RNA trimer (GGA) partitions to release from the enzyme rather than going on to form the full-length elongation complex. A much higher percentage of abortive intermediates is seen in the presence of Lomibuvir, GS-9669, and Filibuvir (29%, 20%, and 13%, respectively). This figure also shows that the fraction of abortive intermediates is nearly constant over time, suggesting a constant kinetic partitioning to release from the enzyme versus transitioning to rapid elongation mode to form the full-length product.

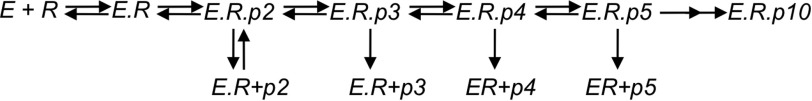

Kinetic Mechanism for Initiation

In Fig. 4C we show the time course for formation of each measureable intermediate and the final 10-nt product in the absence and presence of each NNI2. The concentration of each species was converted from its radioactivity based on a standard curve generated by known concentrations of [α-32P]ATP spotted on the gel. The kinetics are not as expected for a sequence of reactions in series. Namely, there is no lag phase in the formation of the 10-nt product as would be expected if the sequential reactions were comparable in rate. Rather, our results suggest that the first step, the formation of the dinucleotide, is rate-limiting. In addition, the observed accumulation of abortive intermediates is due to their rapid dissociation from the enzyme as described in Scheme 2. Thus only a fraction of the intermediates undergo a transition to the elongation mode and then rapidly go on to form the full-length product. Accordingly the observed “abortive intermediates” appear to represent a sum of the intermediates bound to the enzyme and those that accumulate in solution. Our data support the suggestion that the short oligonucleotides, once released into solution, do not rebind to the enzyme-template RNA complex at a significant rate. Indeed, decades of work document the frustrations in attempting to find conditions to get efficient formation of a stable elongation complex by binding from solution. Formation of a stable elongation complex requires its synthesis from within the active site (7).

SCHEME 2.

Minimal model for initiation kinetics. We model the kinetics of initiation starting with RNA (R) binding to enzyme (E). Then in sequential steps nucleotides (not shown) bind and react to form primers of varying lengths (p2, p3, etc.). The fitting derives apparent rates of reaction for each step in the model, which in reality represents at least two steps. Therefore, the model is used only to capture the essential features of the mechanism and kinetics of initiation rather than defining intrinsic rate constants, which is not possible given the information content of the data relative to the minimal number of steps in the model.

We have modeled the kinetics by computer simulation using the model shown in Scheme 2. It should be noted that if each intermediate was formed and then reacted processively to form the next species, we could model the kinetics explicitly to get the rate constants for each step as we have done for the kinetics of elongation (see Fig. 5D and Ref. 7). However, because the intermediates accumulate with time, it appears that they dissociated from the enzyme and do not rebind. Therefore, the rate and amplitude information that would allow definitive modeling of the rate constants for sequential reactions is lost. In our modeling it is apparent that there are too many rate constants to be defined by the data, and therefore, we do not report individual rate constants. Rather, our modeling demonstrates only that the data can be accounted for by the simple model. Moreover, the sets of rate constants capture the essential features of the underlying model without defining the actual rate constants; namely, rate-limiting formation of the di- and tri-nucleotides followed by fast sequential elongation of various intermediates that partition between continued polymerization versus dissociation from the enzyme at each step in the sequence up to the formation of the five-nucleotide product. According to our modeling, most of the observed trimer is due to accumulation in solution.

These results clearly demonstrate the effects of the NNI2 inhibitors. They do not alter the rates of formation of the di- and tri-nucleotide initiation products but appear to block the transition from initiation to elongation, leading to accumulation of four- and five-nucleotide intermediates. These results suggest that the five-nucleotide RNA duplex may be the largest that can be accommodated in the active site before transition to the elongation mode. Presumably, polymerization beyond the five-nucleotide product is sterically blocked by the β-loop, which must move out of the active site in the transition to the fast, processive elongation mode. That is, the structural transition leading to fast, processive synthesis occurs before the formation of the six-nucleotide product.

Effects of NNI2 on Rates of Elongation

The kinetics of nucleotide incorporation were measured to investigate the effect of each NNI2 on the rates of processive elongation. Fig. 5A shows the protocol used to isolate the stable NS5B/RNA elongation complex and then to monitor the kinetics of elongation after mixing rapidly with all four nucleotides. The reactions were quenched at various time points for up to 20 s. Formation and decay of intermediates leading to full-length primer extension (proceeding from 10–20 nt) in the presence and absence of each NNI2 were resolved on a sequencing gel (Fig. 5B). The time dependence of multiple steps of nucleotide incorporation during processive RNA polymerization was analyzed by global fitting using a minimal model as described previously (7) to get the results shown in Fig. 5, C and D. The average rate of nucleotide incorporation was only slightly altered when NS5B was incubated with the NNI2s. The observed rates were 1.3, 1.3, and 1.47 s−1 with GS-9669, Lomibuvir, and Filibuvir, respectively, compared with 1.5 s−1 with no inhibitor. However, we also noted that the first nucleotide incorporation was much faster than subsequent reactions and that GS-9669 and Lomibuvir slow the rate of this reaction ∼2-fold. However, the faster rate for the first incorporation appears to be due to sequence context effects, consistent with prior studies (7). For example, starting with the 11-nt primer, we show that the rate of the first nucleotide incorporation is comparable to subsequent steps (data not shown).

PPi Release after CTP Incorporation by HCV Elongation Complex

Fig. 6 shows the analysis of the kinetics of PPi release, measured in a fluorescence assay coupled to the hydrolysis of PPi by PPase and the binding of phosphate (Pi) to fluorescently labeled PBP using methods described previously (16). In Fig. 6, A and B, we show the calibration of the coupled assay involving the kinetics of phosphate binding and the kinetics of PPi hydrolysis (monitored by Pi binding to PBP), respectively. Fig. 6C shows the time course of the fluorescence change after mixing the elongation complex with CTP in the presence of the coupled assay system. By fitting the three data sets simultaneously, the kinetics of the coupled assay are included in the interpretation of the signal. The results show that the release of PPi must be faster than the rate of chemistry (measured separately) as summarized in Table 1. One should note that the observable rate of pyrophosphate release cannot be faster than chemistry when the two are measured sequentially. The rate constant governing the chemical reaction limits the observed rate of PPi release. However, in fitting by simulation, we derive a minimal rate constant sufficient so that the observed kinetics of the chemistry step and PPi release are coincident. Accordingly, the rate constants reported in Table 1 represent the minimal rates of PPi release sufficient for the PPi release to be coincident with the observed kinetics of the chemical reaction.

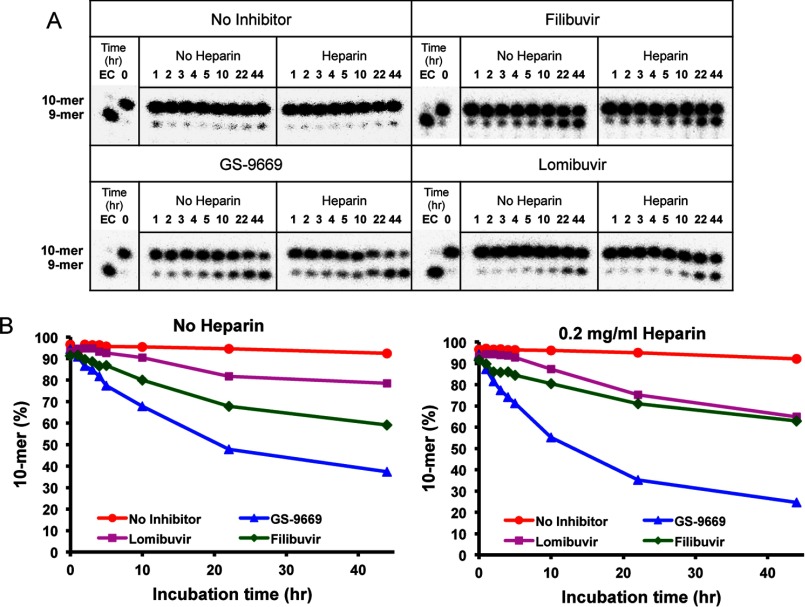

Effects of NNI2 on the Stability of HCV Elongation Complex

We also investigated the stability of the NNI2-bound elongation complex with and without an enzyme trap, 0.2 mg/ml heparin, for up to 44 h. The remaining activity of the elongation complex after various times of incubation was examined by monitoring the ability of the enzyme to incorporate CTP to form a 10-nt product from the 9-nt primer (Fig. 7A), thus providing a measurement of the amount of active elongation complex. The concentration of active elongation complex stayed high during the long time of incubation as first described by Jin et al. (7) but was reduced in the presence of NNI2 (Fig. 7B). These data indicate that the dissociation of the RNA from the NS5B elongation complex during long time incubation was facilitated in the presence of NNI2, perhaps due to a structural change leading to faster release of the primer/template duplex. However, the effect was small and not likely to be physiologically significant given the time scale of the experiment relative to the expected time required to replicate the viral genome in vivo.

FIGURE 7.

Stability of the elongation complex in the presence of NNI2. A, a PAGE gel displaying the stability of the NNI2 bound elongation complex in the elongation buffer with and without heparin. The elongation complex preformed in the presence of NNI2 was incubated in the elongation buffer with and without 0.2 mg/ml heparin. The remaining activity of the elongation complex was examined by reacting with 50 μm CTP for 20 s at indicated incubation time intervals. B, the fraction of the 10-mer primer extension product formation was plotted versus incubation time.

Discussion

We have optimized conditions to examine de novo initiation and elongation catalyzed by the HCV RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, examined the kinetics of initiation, and assessed the effects of four classes of nonnucleoside inhibitors on various stages of polymerization. There are four major conclusions from these studies. 1) The initiation reaction leads to the accumulation of abortive intermediates three-five nucleotides in length, after which a very stable elongation complex is formed. It is important to note that the amplitude of the abortive intermediates formed is not a limited by substrate depletion because nucleotide concentrations were at least 10-fold in excess of the concentration of elongation complex (Fig. 4C). The elongation complex is also formed without evidence of a lag phase, which is contrary to the predictions of any simple sequential polymerization model. Thus, these data suggest that the initiation reaction is rate-limiting and the transition from initiation to elongation mode results in rapid formation of the full-length product. The observed abortive intermediates do not appear to react to form the full-length elongation product but, rather, appear to accumulate into solution. Our data suggest that the transition from initiation to elongation can occur from any intermediate between three and five nucleotides in length.

We have modeled the kinetics of initiation by computer using a minimal model (Scheme 2). Although the individual rate constants are not well constrained by the data, the modeling accurately mimics the essential features of the reaction where any intermediate can dissociate into solution, be elongated by a single base while still in the initiation mode, or transition to a state in which sequential elongation reactions are fast and processive. The model is consistent with the observation that the initiation reaction requires approximately 1 h to approach completion, whereas individual elongation steps occur in a fraction of a second. Thus the minimal features of this model can easily account for the observed reactions with widely varying rates so that intermediates between five and nine nucleotides are not observed; namely, slow initiation/transition followed by fast elongation. In the cell there are thought to be host cell factors or other viral factors in the membrane-associated replisome (possibly NS5A) that recognize viral RNA and facilitate the initiation reaction to greatly increase its efficiency. Our in vitro initiation reaction retains the essential steps in the reaction and must serve as a surrogate for the in vivo initiation until better conditions can be found to increase the efficiency of the steps we have defined. 2) Palm site inhibitors appear to block the initiation reaction involving the formation of the first dinucleotide. This conclusion is inferred from the observation that these inhibitors are largely ineffective when polymerization is initiated using a pGG dinucleotide, where the critical first step of the reaction is bypassed. Because palm site-1 and palm site-2 inhibitors bind in the active site, they are expected to be competitive with the template and/or nucleotide. The surprising result here is that the binding of the pGG overcomes inhibition either because the binding affinity and concentration of pGG in solution exceed the binding affinity and concentration of inhibitor or because the inhibitors specifically block the formation of the dinucleotide from two GTP molecules. Although the current results are suggestive, further studies are required to establish the underlying mechanisms of inhibition and relevant thermodynamic parameters. 3) Thumb site II inhibitors do not significantly block initiation or elongation; rather, they inhibit the transition from initiation to the elongation mode, leading to the accumulation of abortive intermediates three-five nucleotides in length. Little is known and much is speculated about the transition from initiation to elongation, centering on the role of the β-loop that protrudes into the active site from the thumb domain. A recent crystal structure shows that the thumb domain is positioned to participate in the initiation reaction, and mutations in key residues in the β-loop interfere with initiation (8). These data provide strong evidence for the role of the β-loop in the initiation reaction. Moreover, the HCV polymerase does not efficiently bind duplex RNA from solution, but deletion of the β-loop allows for the binding of short duplex RNA and for solution of crystal structures thought to mimic the elongation complex (8, 19, 20). These results suggest that the β-loop catalyzes initiation but then must move out of the active site in the transition from initiation to processive elongation. However a structure of the elongation complex has yet to be published, and details of the β-loop movement are lacking. In addition, structures with short duplex RNA bound to a β-loop-deletion mutant show a more open active site relative to the apoenzyme (8, 21).

In the companion paper we use hydrogen/deuterium exchange kinetics to explore the long range allosteric effects caused by the binding of the NNI2 on the surface of the protein and propagating to the active site (6). Binding of the NNI2 leads to a general rigidification the protein, especially in the area of the active site and the β-loop, consistent with the observation that they inhibit the structural transition. 4) We have further examined the elongation reaction. After the first incorporation, the enzyme must release pyrophosphate and translocate to allow the binding and incorporation of the next nucleotide, and either of these steps may be limited by a conformational change in going from a closed catalytically active state to an open state allowing the release of pyrophosphate and/or translocation (22). Using a fluorescence assay we have shown that the release of pyrophosphate in a single turnover experiment is faster than the subsequent processive elongation reaction. Moreover, the rate of elongation is dependent on the sequence context and/or identity of the base pair, with rates varying >10-fold from 1 base pair to the next. This is unusual among polymerases, and further studies are needed to quantify the sequence context dependence.

We noted a small (2-fold) effect of the NNI2 on slowing the rate of elongation. This observation is consistent with the overall rigidification of the protein as observed by hydrogen/deuterium exchange, described in the companion paper (6), and the suggestion that the rate-limiting step may involve a conformational change. However, the physiological significance of these reactions remains to be established. One possibility is that the polymerase works in concert with the helicase during processive synthesis to unwind duplex RNA and secondary structure in the template.

Our studies on the NNI2 are particularly intriguing because they demonstrate an allosteric action at a distance and illuminate one of the least understood aspects of RNA-dependent RNA polymerization; namely, the transition for initiation to elongation mode. The studies shown here and previously (7) have suggested that the transition from initiation to elongation occurs after the formation of oligonucleotides in the range of 3–5 nucleotides in length. Here, when the transition is blocked, there is a significant accumulation of five-nucleotide products.

In the current models for the initiation and transition, the 3′-end of the template strand enters the active site and directs the synthesis of a dinucleotide and its subsequent extension to three-, four-, and five-nucleotide products. At some point the growing primer gets too big to fit in the active site and pushes the β-loop out of the active site to transition to the processive elongation mode. Here, when the transition is inhibited, the maximum length observed is five nucleotides, leading us to conclude that five nucleotides of duplex may be the largest that can be accommodated in the active site in the presence of the β-loop. Our data indicate that by binding to the outside surface of the thumb domain the NNI2s allosterically inhibit this critical structural transition from the initiation to elongation mode to inhibit RNA replication. To gain insights into the underlying molecular basis for this allosteric inhibition and to examine the observed long range effects on protein structure, hydrogen/deuterium exchange kinetics are explored in the companion paper (6).

Author Contributions

J. L. performed the experiments and prepared the figures. J. L. and K. A. J. designed the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper. Both authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

Nonnucleoside inhibitors were a gift from Gilead Sciences, Inc.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant 1R01AI110577 (NIAID; to K. A. J.) and the Welch Foundation (F-1604 to K. A. J.). K. A. J. is the president of KinTek, which provided the RQF-3 rapid quench-flow instrument and KinTek Explorer software used in this study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- HCV

- hepatitis C virus

- NS5B

- nonstructural protein 5B

- NNI2

- thumb site 2 nonnucleoside inhibitor

- PPase

- pyrophosphatase

- MDCC

- 7-diethylamino-3-((((2maleimidyl)ethyl)amino)carbonyl)coumarin

- PBP

- MDCC-labeled phosphate-binding protein

- nt

- nucleotide(s).

References

- 1. Shepard C. W., Finelli L., and Alter M. J. (2005) Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5, 558–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chak E., Talal A. H., Sherman K. E., Schiff E. R., and Saab S. (2011) Hepatitis C virus infection in U.S.A.: an estimate of true prevalence. Liver Int. 31, 1090–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Muir A. J., and Naggie S. (2015) Hepatitis C Virus Treatment: Is it Possible to Cure all Hepatitis C Virus Patients? Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 13, 2166–2172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilder J. M., Jeffers L. J., Ravendhran N., Shiffman M. L., Poulos J., Sulkowski M. S., Gitlin N., Workowski K., Zhu Y., Yang J. C., Pang P. S., McHutchison J. G., Muir A. J., Howell C., Kowdley K., Afdhal N., and Reddy K. R. (2016) Safety and efficacy of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir in African Americans with hepatitis C virus infection: a retrospective analysis of Phase 3 data. Hepatology 63, 437–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zeuzem S., Jacobson I. M., Baykal T., Marinho R. T., Poordad F., Bourlière M., Sulkowski M. S., Wedemeyer H., Tam E., Desmond P., Jensen D. M., Di Bisceglie A. M., Varunok P., Hassanein T., Xiong J., Pilot-Matias T., DaSilva-Tillmann B., Larsen L., Podsadecki T., and Bernstein B. (2014) Retreatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 1604–1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deredge D., Li J., Johnson K. A., and Wintrode P. (2016) Hydrogen/deuterium exchange kinetics demonstrate long range allosteric effects of Thumb site 2 inhibitors of Hepatitis C viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Biol. Chem. 291, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jin Z., Leveque V., Ma H., Johnson K. A., and Klumpp K. (2012) Assembly, purification, and pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of active RNA-dependent RNA polymerase elongation complex. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 10674–10683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Appleby T. C., Perry J. K., Murakami E., Barauskas O., Feng J., Cho A., Fox D. 3rd, Wetmore D. R., McGrath M. E., Ray A. S., Sofia M. J., Swaminathan S., and Edwards T. E. (2015) Viral replication: structural basis for RNA replication by the hepatitis C virus polymerase. Science 347, 771–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jin Z., Leveque V., Ma H., Johnson K. A., and Klumpp K. (2013) NTP-mediated nucleotide excision activity of hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E348–E357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Spence R. A., Kati W. M., Anderson K. S., and Johnson K. A. (1995) Mechanism of inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by nonnucleoside inhibitors. Science 267, 988–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kati W. M., Johnson K. A., Jerva L. F., and Anderson K. S. (1992) Mechanism and fidelity of HIV reverse transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 25988–25997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kellinger M. W., and Johnson K. A. (2010) Nucleotide-dependent conformational change governs specificity and analog discrimination by HIV reverse transcriptase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 7734–7739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kellinger M. W., and Johnson K. A. (2011) Role of induced fit in limiting discrimination against AZT by HIV reverse transcriptase. Biochemistry 50, 5008–5015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirmizialtin S., Nguyen V., Johnson K. A., and Elber R. (2012) How conformational dynamics of DNA polymerase select correct substrates: experiments and simulations. Structure 20, 618–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Watkins W. J., Ray A. S., and Chong L. S. (2010) HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitors. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 13, 441–465 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hanes J. W., and Johnson K. A. (2008) Real-time measurement of pyrophosphate release kinetics. Anal. Biochem. 372, 125–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnson K. A., Simpson Z. B., and Blom T. (2009) FitSpace Explorer: an algorithm to evaluate multidimensional parameter space in fitting kinetic data. Anal. Biochem. 387, 30–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson K. A., Simpson Z. B., and Blom T. (2009) Global Kinetic Explorer: a new computer program for dynamic simulation and fitting of kinetic data. Anal. Biochem. 387, 20–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chinnaswamy S., Yarbrough I., Palaninathan S., Kumar C. T., Vijayaraghavan V., Demeler B., Lemon S. M., Sacchettini J. C., and Kao C. C. (2008) A locking mechanism regulates RNA synthesis and host protein interaction by the hepatitis C virus polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20535–20546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bressanelli S., Tomei L., Rey F. A., and De Francesco R. (2002) Structural analysis of the hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase in complex with ribonucleotides. J. Virol. 76, 3482–3492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mosley R. T., Edwards T. E., Murakami E., Lam A. M., Grice R. L., Du J., Sofia M. J., Furman P. A., and Otto M. J. (2012) Structure of hepatitis C virus polymerase in complex with primer-template RNA. J. Virol. 86, 6503–6511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hanes J. W., and Johnson K. A. (2007) A novel mechanism of selectivity against AZT by the human mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 6973–6983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]