Abstract

The biosynthesis of Fe-S clusters is a vital process involving the delivery of elemental iron and sulfur to scaffold proteins via molecular interactions that are still poorly defined. We reconstituted a stable, functional complex consisting of the iron donor, Yfh1 (yeast frataxin homologue 1), and the Fe-S cluster scaffold, Isu1, with 1:1 stoichiometry, [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24. Using negative staining transmission EM and single particle analysis, we obtained a three-dimensional reconstruction of this complex at a resolution of ∼17 Å. In addition, via chemical cross-linking, limited proteolysis, and mass spectrometry, we identified protein-protein interaction surfaces within the complex. The data together reveal that [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 is a roughly cubic macromolecule consisting of one symmetric Isu1 trimer binding on top of one symmetric Yfh1 trimer at each of its eight vertices. Furthermore, molecular modeling suggests that two subunits of the cysteine desulfurase, Nfs1, may bind symmetrically on top of two adjacent Isu1 trimers in a manner that creates two putative [2Fe-2S] cluster assembly centers. In each center, conserved amino acids known to be involved in sulfur and iron donation by Nfs1 and Yfh1, respectively, are in close proximity to the Fe-S cluster-coordinating residues of Isu1. We suggest that this architecture is suitable to ensure concerted and protected transfer of potentially toxic iron and sulfur atoms to Isu1 during Fe-S cluster assembly.

Keywords: frataxin, Friedreich ataxia, iron-sulfur protein, mitochondria, protein complex

Introduction

Fe-S clusters are highly versatile cofactors that both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells utilize in many essential metabolic pathways (1). In yeast and animal cells, mitochondria assemble Fe-S clusters autonomously, whereas other cellular compartments depend on precursors and/or signals generated by mitochondria (2). A complete loss of mitochondrial Fe-S cluster synthesis is therefore lethal, while partial defects typically result in mitochondrial dysfunction, multiple Fe-S enzyme deficits throughout the cell, and global iron imbalance (1). In humans, inherited defects in mitochondrial Fe-S cluster synthesis have been linked to the neurodegenerative disease Friedreich ataxia and to various tissue-specific conditions, although the role of this process in human disease is most likely underestimated (3).

Even though Fe-S clusters can assemble spontaneously in vitro (4), protected and safe Fe-S cluster synthesis in mitochondria requires several specialized proteins, most of which were inherited from the main bacterial Fe-S cluster assembly pathway (ISC pathway) (5, 6). Thus, in both bacteria and mitochondria, Fe-S cluster assembly is centered around IscU-type protein scaffolds (bacterial IscU/yeast Isu1) upon which new Fe-S clusters are assembled using the following proteins: (i) a pyridoxal phosphate-dependent cysteine desulfurase (bacterial IscS/yeast Nfs1) with a stabilizing binding partner in eukaryotes (yeast Isd11) that serve as the sulfur donor (1); (ii) the iron-binding protein frataxin (bacterial CyaY/yeast Yfh1) that serves as the iron donor (7–10) as well as a regulator of the cysteine desulfurase activity (11, 12); and (iii) the electron donor chain formed by ferredoxin reductase and ferredoxin (13).

Although all of the proteins described above work together to ensure the concerted delivery of iron, sulfur, and reducing equivalents to their cognate IscU-type scaffolds, the architecture of the complexes and sub-complexes formed by these proteins is not well defined, and an integrated mechanism for Fe-S cluster assembly is still lacking. The crystal structure of an Escherichia coli [IscS]·[IscU] complex (PDB3 code 3LVL) showed an elongated heterodimer consisting of one IscS and one IscU subunit (14), and furthermore the crystal structure of an Archaeoglobus fulgidus [IscS]2·[IscU]2 complex (PDB code 4EB5) showed an elongated heterotetramer consisting of two IscS and two IscU subunits (15). Additional studies demonstrated similar bacterial and yeast heterotetramers in which a dimer of IscS/Nfs1 binds to one IscU/Isu1 monomer at each end, and it was further proposed that one CyaY/Yfh1 monomer could bind in a pocket between the cysteine desulfurase and the scaffold (10, 16–18). Models based on these structures have also been proposed for the human proteins (19, 20). Of relevance to this study, the current model for the yeast Fe-S cluster assembly machinery is a complex of [Nfs1]2·[Isd11]2·[Isu1]2·[Yfh1]2 containing one [2Fe-2S] cluster assembly site at each end of the molecule (10, 17). The mechanism of sulfur transfer to each of these sites is thought to involve a flexible loop of Nfs1 containing the invariant cysteine residue Cys-421, which becomes persulfurated at the end of the cysteine desulfurase reaction (12). Binding of Yfh1 to Nfs1 was shown to stimulate binding of the cysteine substrate to Nfs1, presumably by facilitating access to the substrate-binding site located in a pocket within the protein. The subsequent formation of the persulfurated cysteine on the flexible loop of Nfs1 was Yfh1- and iron-independent but required the presence of Isd11 (12). Thus, two conformational changes were proposed to take place in Nfs1 for sulfur donation to Isu1: the first induced by Yfh1 binding, which would expose the Nfs1 substrate-binding site, and the second induced by Isd11, which would bring the flexible loop of Nfs1 close to the substrate-binding site allowing formation of the persulfurated cysteine. It was also postulated that further displacement of the Nfs1 flexible loop would be required to move the persulfurated cysteine close to the Fe-S cluster assembly site and thereby allow sulfur donation from the persulfurated cysteine to Isu1 (17). On the other hand, the molecular details of iron donation from Yfh1 to Isu1 remain largely undefined. One monomer of Yfh1 was proposed to bind in a pocket between Nfs1 and Isu1 through its iron-binding surface (10, 18). However, a protein docking study further suggested that Yfh1 binding would only be possible with the flexible loop of Nfs1 positioned inside the cysteine substrate-binding site rather than in proximity of the Fe-S cluster assembly site. This implies that iron and sulfur donation would have to occur sequentially and that sulfur donation would require the displacement of Yfh1 from the Fe-S cluster assembly complex (17), which is in contrast with the general consensus that Fe-S cluster assembly requires the simultaneous binding of the scaffold to both the cysteine desulfurase and the iron donor (1, 2).

One aspect that has been largely overlooked, but may actually help shed light on the iron-donation mechanism, is the fact that Yfh1 and its bacterial and human orthologues have a strong propensity to oligomerize in vitro (7, 9, 21, 22) and in vivo (9, 23, 24). At an Fe2+ to protein ratio of 2, monomeric Yfh1 is converted to trimer in solution (21, 22); and at higher Fe2+ to protein ratios, the trimer serves as the building block for the assembly of larger oligomers (22, 25). Yfh1 oligomerization is normally coupled to the Yfh1-catalyzed oxidation of Fe2+ that leads to formation of a stable ferric mineral within the Yfh1 oligomers (26–28). Yfh1 oligomers disassemble upon treatment with chelators and/or reducing agents, indicating that iron oxidation and mineralization are required for oligomer stabilization (21, 28); and indeed, mutations that affect the ferroxidase activity of Yfh1 also affect its ability to oligomerize (22), and similarly, anaerobic conditions that inhibit Fe2+ oxidation stabilize the Fe2+-loaded Yfh1 monomer (29). These properties are manifested in yeast, where Yfh1 oligomerizes in response to rapid increases in mitochondrial iron uptake (23, 24). In addition, certain point mutations (Y73A and T118A/V120A) enable Yfh1 to form trimer at basal mitochondrial iron levels (24). Thus, in yeast mitochondria, wild type Yfh1 is normally monomeric whereas the Yfh1Y73A variant is trimeric, and both proteins assemble into higher order oligomers when mitochondrial iron levels increase (24). As compared with wild type Yfh1, the Yfh1Y73A variant exhibits faster assembly kinetics in yeast that correlate with higher levels of activity of the [4Fe-4S] enzyme aconitase, reduced oxidative damage, and increased yeast survival, suggesting that Yfh1 oligomerization responds to dynamic changes in mitochondrial iron uptake and enables Yfh1 to simultaneously promote Fe-S cluster biosynthesis and stress tolerance (24). Similar to the yeast system, overexpression of wild type Yfh1 in E. coli yields monomeric protein that can oligomerize in an iron-dependent manner in vitro as described above. In contrast, overexpression of the Yfh1Y73A variant in E. coli yields trimer as well as smaller levels of Yfh1Y73A 24-mer that form as a result of increasing trimer concentrations during protein overexpression (8, 25).

When purified from E. coli, Yfh1Y73A trimer contains no measurable iron (25) and Yfh1Y73A 24-mer contains only traces of iron (8). The availability of these iron-free functional oligomers has enabled structural studies that together have revealed the importance of the N-terminal region for Yfh1 oligomerization (25, 30). In particular, the Y73A mutation was shown to stabilize this region and thereby facilitate subunit-subunit interactions involved in the assembly of both trimer and higher order oligomers, independent of the presence of iron or other metals (25, 30). By uncoupling oligomerization of Yfh1 from iron binding and oxidation, the Y73A mutation makes Yfh1 similar to human frataxin, which has an iron-independent mechanism of oligomerization involving its N-terminal region (9). However, the Y73A mutation has no effects on the function of Yfh1, including an ability to bind, store, and deliver iron for Fe-S cluster synthesis in the presence of Isu1, [Nfs1]·[Isd11], and l-cysteine (8).

The structural studies mentioned above have also provided insights on how oligomerization enables iron binding and storage by Yfh1. In an x-ray crystallographic structure obtained from the iron-loaded Yfh1Y73A trimer, one atom of iron was found to bind inside a channel at the 3-fold axis, coordinated by each of the three subunits of the trimer via the invariant residue Asp-143 (25). The channel could exist in two different conformations with different metal binding affinities, suggesting that the Yfh1 trimer may control when the bound iron is transferred to Isu1. In a model of the Yfh1 hexamer obtained from small angle x-ray scattering data, one atom of iron was found to bind at the interface between two trimers, close to conserved residues that include the ferroxidation and mineralization sites of Yfh1, consistent with the role of iron oxidation in the stabilization of higher order Yfh1 oligomers (22, 28). Finally, the structures of the apo- and holo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer revealed a hollow globular particle made up of eight trimers, with striking similarities to the iron-storage protein ferritin, including an ability to form a ferric iron core inside its central cavity (25, 31).

IscU-type scaffolds are also known to exist in monomeric (32, 33) and homo-oligomeric states in the absence of protein partners (34, 35). In particular, the yeast orthologue, Isu1, has been isolated as a primarily monomeric (10) or dimeric species (8, 36) upon overexpression in E. coli. Available structures of monomeric IscU proteins from E. coli and Haemophilus influenzae show a flexible N-terminal region connected to a globular core formed by four α-helices packed against three antiparallel β-strands (32, 33), with the Fe-S cluster binding site residing in a solvent-accessible region at one end of the globular core (37, 38). Interestingly, the structure of an asymmetric IscU trimer from A. aeolicus revealed one [2Fe-2S] cluster bound on the surface of one subunit but buried inside the interface formed by all three subunits (34). These species may not be fully representative of the active forms of IscU-type scaffolds, however, as cluster assembly activity requires binding of the scaffold to the iron and the sulfur donor as well as other specialized proteins (5, 6), which may result in conformational changes that are only partially defined (39).

To begin to explain how Yfh1-bound iron could be delivered during Fe-S cluster assembly, we previously studied the interactions of the holo-Yfh1 and apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mers with Isu1 and [Nfs1]·[Isd11] (8). Isu1 and [Nfs1]·[Isd11] could bind to holo-Yfh1 24-mer upon its iron-dependent assembly. Moreover, these protein-protein interactions could be made iron-independent by use of the apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer, which assembles in an iron-independent manner as described above. Importantly, the ability to store iron as a stable mineral enabled both the Yfh1 or Yfh1Y73A 24-mer to release iron only when both Isu1 and elemental sulfur were available (8). We proposed that oligomerization of Yfh1 promotes simultaneous interactions of Yfh1 and [Nfs1]·[Isd11] with Isu1, leading to the concerted delivery of iron and sulfur to the Fe-S cluster-coordinating site. To further define the underlying mechanisms, we set out to assess the subunit composition and stoichiometry, protein-protein interaction surfaces, and overall architecture of the Fe-S cluster assembly complexes formed with oligomeric Yfh1. Here, we report the initial structural characterization of a stable functional complex consisting of the apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer and stoichiometric amounts of Isu1. The architecture of the complex suggests a coordinated mechanism for the simultaneous transfer of iron and sulfur to Isu1 for the synthesis of [2Fe-2S] clusters.

Experimental Procedures

Preparation of [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 Protein Complex

Previously published procedures were used for purification of apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer (25), Isu1, and [Nfs1]·[Isd11] (8). Apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer and [Nfs1]·[Isd11] were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. As reported previously, Isu1 assembled spontaneously during overexpression in E. coli and was purified as a distribution containing dimer and smaller amounts of monomer and trimer (8). Isu1 was purified in the presence of 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol (added fresh at each step of the purification), was kept at 4 °C also in the presence of 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and was used within a week. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA kit (Thermo Scientific) or the absorbance and extinction coefficient (ϵ280 = 20,000 m−1 cm−1 for Yfh1 and ϵ280 = 5960 m−1 cm−1 for Isu1) and are expressed per subunit. The [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex was prepared by incubating 40 μm apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer and 60 μm Isu1 (1:1.5 molar ratio) at 30 °C for 30 min in buffer containing 10 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.3, 100 mm NaCl (HN100 buffer), and 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol. The reactions were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min and then loaded onto a Sephacryl S300 gel filtration column equilibrated with HN100 buffer. Fractions were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 15% CriterionTM precast gels (Bio-Rad) with SYPRO Orange staining (Life Technologies, Inc.). To assess the Yfh1:Isu1 stoichiometry, the complex was isolated by Sephacryl S300 size-exclusion chromatography. Aliquots of fractions containing the complex were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, as described above, along with known amounts of purified Yfh1 and Isu1 proteins that served as internal standards. The density of each protein band was quantified using a Bio-Rad Gel DocTM XR+ with Image Lab 5.0 software, and the levels of Yfh1 and Isu1 present in the complex were calculated relative to the standards. This analysis was repeated with seven independent complex preparations.

Iron Measurements

Iron was measured at the Metals Laboratory, Mayo Clinic, using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer in collision cell mode. Briefly, aqueous acidic calibration standards were diluted with aqueous acidic diluent containing internal standards. Quality control, blank, and unknown samples (including gel filtration buffer without protein) were diluted in an identical manner. The samples were aspirated into a pneumatic nebulizer, and the resulting aerosol was directed into the plasma by a flow of argon where it was vaporized, atomized, and ionized. Helium gas was used to remove polyatomic interferences, and the quadrupole mass spectrometer was used to detect the analyte ion count per internal standard ion count.

Dynamic Light Scattering

Measurements were performed using a DynaPro Molecular Sizing Instrument with Dynamics Version 6 software (Protein Solutions, Inc.). The system contains an 824.7-nm laser diode and detector that measures scattered light at a 90° angle to the incident beam. Fractions eluted from the Sephacryl S300 gel filtration column were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, after which the supernatant was transferred to a cuvette. After ∼50 counts of 5 s each per measurement, the averaged autocorrelation function was generated, and the particle translational diffusion coefficient was extracted. The hydrodynamic radius (Rh) was calculated using the diffusion coefficient and Stokes-Einstein equation.

Negative Staining Transmission Electron Microscopy (EM)

Fraction 53 freshly eluted from the Sephacryl S300 gel filtration column was diluted to 0.008–0.2 mg/ml in HN100 buffer and applied to carbon-coated glow-discharged (DV-502A instrument, Denton Vacuum Inc.) copper grids (400 mesh, EMS). After optimization, protein concentrations between 0.08 and 0.16 mg/ml were found to give the best distribution of particles on the grids. Each grid was first preincubated for 1 min on a 20-μl HN100 buffer drop on Parafilm M® (Bemis Co., Inc.). Excess buffer was blotted, and the grid was then placed on an 11-μl drop of protein sample for 1 min. Excess protein sample was blotted, and the grid was then washed for 3 s by placing it on a drop of sterile water. After excess water was blotted, the grid was stained with 1% (w/v) uranyl acetate for 1 and 30 s by successively placing it on two separate drops of uranyl acetate, with excess stain drawn off after each step. The grid was then left to dry on forceps for at least 30 min and stored at room temperature. Electron micrographs were collected at the University of Minnesota Characterization Facility using an FEI Tecnai G2 F30 field emission gun cryo-transmission electron microscope with acceleration voltage at 300 V equipped with an Electron Energy-Loss Gatan imaging filter with 4k × 4k ultra scan CCD camera (4096 × 4096 pixels). Images were collected at the magnification of 115,000-fold (1.034 Å/pixel) and were processed using the EMAN2 software package (40).

Docking of Yfh1Y73A Trimer and Isu1 Monomer Structures into the EM Density Map

The program Chimera (41) was used to visualize and dock structures into the EM density map of the refined three-dimensional model. We used the x-ray crystal structure of the Yfh1Y73A trimer with the entire N-terminal region (residues 52–172) resolved (30) (PDB code 3OEQ). Essentially identical homology models of the Isu1 monomer were generated by the I-TASSER web resource (42) and by Phyre2 using the NMR structure of H. influenzae IscU, and the I-TASSER model was then used for docking.

Molecular Dynamics Flexible Fitting for Docked Structures

The N terminus of Isu1 (residues 28–61), which had been removed for the initial docking, was modeled into an unoccupied nearby volume of the EM map manually, while aided by cross-linking data. The N terminus of Yfh1 was also rearranged and modeled into the EM map based on cross-linking data. The EM map was then converted to Situs format to allow rigid-body docking of the entire complex structure, followed by molecular dynamics simulations and energy minimizations using nanoscale molecular dynamics, NAMD 2.10 (43). The Molecular Dynamics Flexible Fitting method used NAMD to perfect the complex structure while simultaneously improving its fit to the EM map (44, 45). The CHARMM22 force field was used in vacuum with a dielectric constant of 80, a constant simulation temperature of 50 K, and Langevin dynamics coupled with a damping constant of 5 ps−1. Harmonic restraints for amine N, carbonyl C, and α-C atoms were applied to maintain the model 4, 3, 2 symmetry with a symmetry force constant of 20 for 100 ps (200 steps) (45). Harmonic restraints were also applied to maintain chirality and secondary structure. Iterations of model improvement were done with the program Coot (46), followed by molecular dynamics simulations and energy minimizations using NAMD 2.10 against the EM map, and were repeated until a plausible model of the complex was created that closely matched the initial Yfh1Y73A trimer crystal structure and Isu1 monomer homology model. A Ramachandran plot showed 92% of residues were in the favorable region. The MolProbity score of the final model was 2.60 (42%) with only 2.14% β-carbon deviations >0.25 Å, indicating that the model had reasonable geometry (47). This MolProbity score reflects protein quality statistics and is a log-weighted combination of clash score, percentage Ramachandran not favored, and percentage of bad chain rotomers. In addition, β-carbon deviations >0.25 Å provide a measure of improper dihedrals in the calculated structure (47).

Chemical Cross-linking, Limited Proteolysis, and Tandem Mass Spectrometry

We used the cross-linker bis[sulfosuccinimidyl] suberate (BS3) (Thermo Scientific), a monobifunctional N-hydroxysuccinimide ester that reacts primarily with the ϵ-amino group of the side chain of lysine residues and the α-amino group of the N terminus of polypeptides and more weakly with the OH group of the side chains of tyrosine, threonine, or serine residues (48, 49). The [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex (1 ml containing 4 mg of total protein) was incubated with BS3 at a protein/BS3 molar ratio of 1:100 for 30 min at room temperature, and the reaction was quenched by addition of 1 m Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, to a final concentration of 20 mm. The reaction mixture was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min, and the cross-linked complex was re-isolated via Sephacryl S300 size-exclusion chromatography to remove excess cross-linker. For limited proteolysis, 20 μg of cross-linked or uncross-linked complex was incubated with 1 μg of the endoproteinase GluC (New England Biolabs) in a total volume of 40 μl at 37 °C. A time course of digestion was analyzed by SDS-PAGE to demonstrate that uncross-linked complex was completely digested in 17 h, while 40 h of incubation was needed to achieve ≥95% digestion of the cross-linked complex. The digestion reaction was terminated by addition of 0.5% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid. The cross-linked peptides were identified at the Mayo Clinic Proteomics Core by nano-flow liquid chromatography electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) using an Orbitrap Elite Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a Thermo Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano HPLC system. The digested peptide mixture was loaded onto a 250-nl OPTI-PAK trap (Optimize Technologies) custom-packed with Michrom Magic C18 solid phase (Michrom Bioresources). Chromatography was performed using 0.2% (v/v) formic acid in both solvent A (98% water, 2% acetonitrile (v/v)) and solvent B (80% acetonitrile, 10% isopropyl alcohol, 10% water (v/v)), using a 2% B to 40% B gradient over 60 min at 325 nl/min through a PicoFrit Magic C18, 3 μm, 75 μm × 250 mm column (New Objective). The mass spectrometer was set to perform a Fourier transform full scan from 340 to 1600 m/z at a resolution of 120,000 (400 m/z resolving power), followed by higher energy collisional dissociation orbitrap MS/MS scans on the top 15 ions at a resolution of 15,000. The MS scan 1 automatic gain control target was set to 1e6, and the MS scan 2 target was set to 5e5 with maximum ion injection times of 50 and 100 ms, respectively. Dynamic exclusion placed selected ions on an exclusion list for 30 s (50, 51). Two different preparations of the complex were independently subjected to chemical cross-linking, limited proteolysis, and MS/MS as described above, the first in the absence and the second in the presence of the reducing agent, tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (50 mm final concentration) (Hampton Research).

Analysis of Cross-linked Peptides

We used the StavroX 3.5.1 program (52) to generate a list of cross-linked peptides, including cross-links between Yfh1 and Isu1 and cross-links within Yfh1 or Isu1, identified by the two independent MS/MS analyses described above. Based on the amino acid sequences of Yfh1 and Isu1, the molecular weight and amino acid specificity of BS3, and the cleavage specificity of GluC, the software calculated all theoretical possible combinations of cross-linked peptides and compared them with the precursor peptide masses in the MS file (52). Each identified cross-linked peptide was then assigned a score based on a comparison between the theoretical fragmentation and the actual MS/MS spectrum of the cross-linked peptide (52). The software also calculated the false discovery rate (FDR) by comparing the number of candidates in each of the two experimental datasets to the number of false-positive candidates from a decoy dataset, created from the inverted amino acid sequences of Yfh1 and Isu1. For each dataset, the software identified a score range within which candidates had an FDR ≤5%, which are shown in Table 1 and supplemental Table S1. Cross-links were identified for all six Lys residues in Yfh1, all 15 Lys residues in Isu1, the Yfh1 and Isu1 N termini, and some additional Tyr, Thr, and Ser residues as shown in detail in supplemental Table S1. Protein-protein distances were measured between each possible pair of cross-linked residues within each of the identified cross-linked peptides in the entire complex structure using a script (distance :resi#1.subunit#1@CA :resi#2.subunit#2@CA) in the command line of Chimera (41). The mean distance ± S.D. was calculated for each possible pair of cross-linked residues (supplemental Table S1). As BS3 has a space arm of 11.4 Å, we assumed that the distance constraint between the backbone α-carbons of two cross-linked residues should be equal to the length of the BS3 spacer arm + the lengths of the side chains of the two cross-linked residues. For example, in the case of Lys-Lys cross-links, the distance constraint is ≤24.0 Å (11.4 + 6.3 + 6.3 Å). The distance constraints for all of the possible pairs of residues that can be cross-linked by BS3 are shown in the legend of supplemental Table S1, and distances measured in the structure that are equal or lower than the distance constraints are highlighted in light gray in supplemental Table S1. In addition, we assumed that the maximum allowable distance constraint between the backbone α-carbons of two cross-linked residues should be equal to the distance constraint plus the estimated resolution-dependent errors (RDE) determined as per Blow (53) in the positions of Yfh1 and Isu1 protein atoms. The RDE for Yfh1-Isu1 (7.8 Å), Yfh1-Yfh1 (10.2 Å), and Isu1-Isu1 (5.4 Å) were calculated from the resolution of the Yfh1Y73A crystal structure used for docking (PDB code 3OEQ; RDE = 5.1 Å) and the resolution of the crystal structure of A. aeolicus IscU (PDB code 2Z7E; RDE = 2.7 Å) used for I-TASSER homology modeling of Isu1 (53). Distances measured in the structure that are equal to or lower than the maximum allowable distance constraints are highlighted in dark gray in supplemental Table S1, and all greater distances are highlighted in yellow.

TABLE 1.

Summary of cross-linking results

Cross-linked peptides with FDR ≤5% were identified, and the distance constraints and maximum allowable distance constraints between different pairs of cross-linked residues were calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Agreement between the simulated three-dimensional structure and any given cross-linked peptide was established as described under “Results.” The data summarized in this table are shown in detail in supplemental Table S1.

| Cross-linked partners | Total cross-linked peptides | Cross-linked peptides that support three-dimensional structure based on distance constraints | Cross-linked peptides that support three-dimensional structure based on maximum allowable distance constraints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yfh1-Isu1 | 34 | 28 (82%) | 6 (18%) |

| Yfh1-Yfh1 | 29 | 23 (79%) | 6 (21%) |

| Isu1-Isu1 | 7 | 7 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

Analysis of Yfh1-Isu1 Interfaces

The coordinate file of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex structure was uploaded into the PISA program (54) and the Interfaces algorithm was used to identify Yfh1-Isu1, Yfh1-Yfh1, and Isu1-Isu1 interfaces and buried surface areas thereof.

Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Assay

Iron-sulfur cluster assembly assays were performed as described previously (8). Briefly, all buffers and solutions were purged with argon gas (<0.2 ppm O2) in vials tightly sealed with rubber septa. The uncross-linked or cross-linked complex (25 μm total protein concentration) was aerobically loaded with Fe2+ (50 μm) for 1 h, and [2Fe-2S] cluster formation was subsequently measured anaerobically in a Beckman Du 640B spectrophotometer at A426 using tightly sealed, argon-purged quartz cuvettes. The source of sulfur for the reaction was either 2.5 mm Na2S or 2 mm l-cysteine in the presence of 5 μm [Nfs1]·[Isd11].

Nfs1 Modeling

The homology model for yeast Nfs1 was created using I-TASSER (42), and the model with the highest confidence score (−1.14) was chosen. Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) and [2Fe-2S] cluster were modeled based on the A. fulgidus [IscS]2·[IscU]2 complex structure (PDB code 4EB5).

Results

Isolation and Functional Characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae [Yfh1]n·[Isu1]n Complex

By use of size-exclusion chromatography coupled with pulldown assays and measurements of Fe-S cluster assembly kinetics, we previously demonstrated that oligomeric Yfh1, including holo-Yfh1 or apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer, forms a stable and functional complex with Isu1 (8). Here, we set out to define the architecture of this complex by use of negative staining transmission EM and chemical cross-linking. To characterize the complex independent of the presence of iron, we assembled the complex using apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer and Isu1, which are produced during overexpression of the corresponding monomers in E. coli (8). As reported previously, apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer preparations contained mostly 24-mer with low levels of trimer, and Isu1 preparations contained mostly dimer and lower levels of monomer and trimer (8). Only traces of bound iron were detected in independent preparations of apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer and Isu1 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary of iron measurements

The indicated proteins were purified, and bound iron was measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The letter n indicates the number of independent protein preparations analyzed. The molar iron/subunit ratio was calculated from the iron concentration and the Yfh1 and/or Isu1 protein concentration measured in each sample. In the case of [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24, the [Yfh1]·[Isu1] heterodimer was considered as one subunit of the complex.

| Protein | Atoms of iron per subunit |

|---|---|

| [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 | 0.061 ± 0.013 (n = 3) |

| Isu1 | 0.003 ± 0.002 (n = 6) |

| Apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer | 0.055 ± 0.004 (n = 3) |

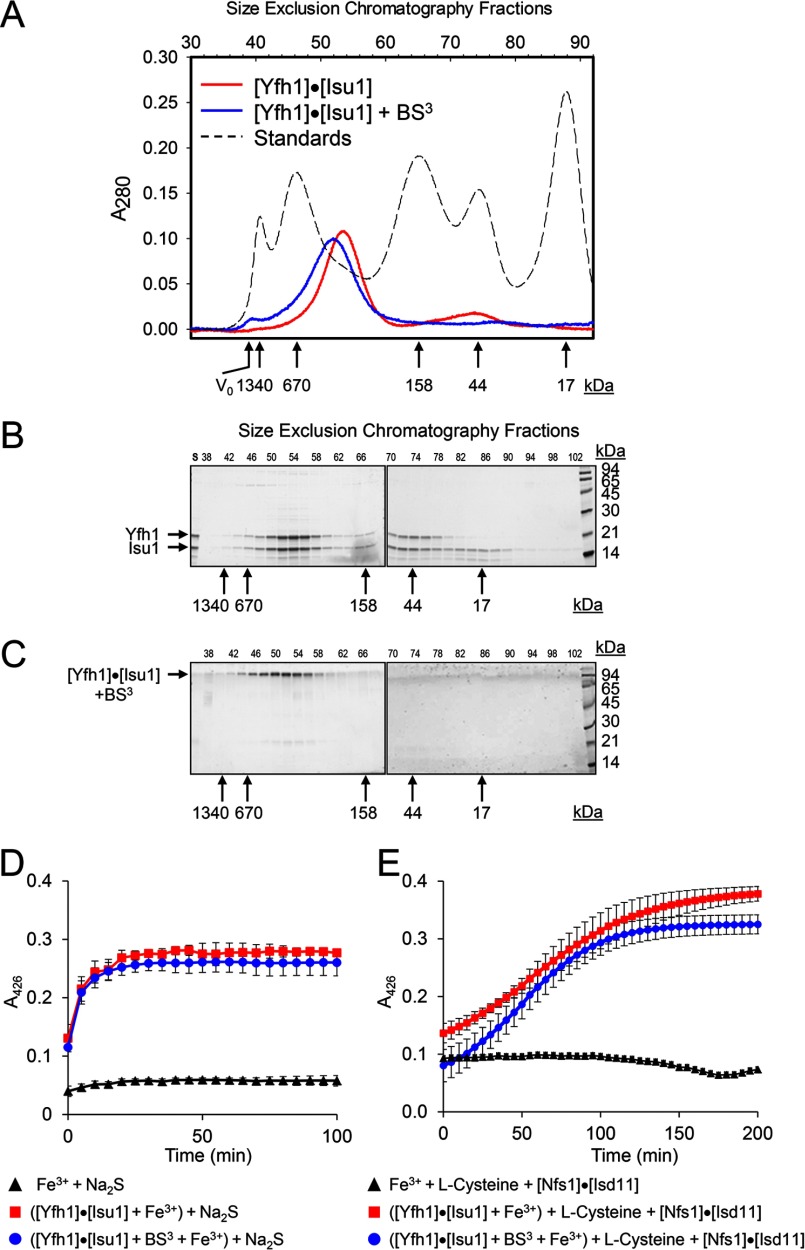

[Yfh1]n·[Isu1]n complex was reconstituted as reported previously (8) by incubating apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer and Isu1 at a molar ratio of 1 to 1.5 (protomer/protomer). Size-exclusion chromatography revealed one major peak (Fig. 1, A and B, fractions 52–56) with an apparent molecular mass of ∼330 kDa (measured at the center of the peak; i.e. fraction 53), and a minor peak with apparent molecular mass of ∼44 kDa (Fig. 1, A and B, fractions 70–76). SDS-PAGE of the fractions eluted from the column showed that the two peaks contained equivalent levels of Yfh1 and Isu1 (Fig. 1B), whereas Isu1 in excess of Yfh1 eluted alone in lower molecular weight fractions (Fig. 1B, fractions 84–90). These data confirmed our previous observation that Isu1 binds to the apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer and also binds to low levels of the Yfh1Y73A trimer that are normally present in 24-mer preparations (8). We measured Yfh1 and Isu1 protein molarity in seven independently prepared complexes using fractions 52–54, which comprise the center of the peak containing the complex (Fig. 1A). Because we used fraction 53 for all EM and cross-linking studies, this fraction was measured in three complexes, whereas fractions 52 and 54 were measured in all of the seven complexes. From the averaged Yfh1:Isu1 stoichiometry measured in fractions 52 and 53 (when available) and 54 in each individual complex, we obtained a mean stoichiometry of 1.07 ± 0.11 (n = 7; range = 0.92–1.26; median = 1.10). We also measured levels of bound iron in three independently prepared complexes using fractions 52–54, and once again we detected very low levels of iron, consistent with the levels measured in each of the two components of the complex (Table 2). The measured iron levels correspond to only ∼1.5–1.8 atoms of iron present per complex (calculated as described in Table 2), which most likely reflects the ability of the complex to bind adventitious iron present in the buffer. These data confirm our previous finding that Isu1 can bind to Yfh1 in an iron-independent manner (8).

FIGURE 1.

Isolation and functional characterization of S. cerevisiae [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex. Purified apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer (40 μm) was incubated with purified Isu1 (60 μm), and the sample was then analyzed by Sephacryl S300 size-exclusion chromatography. For limited proteolysis studies, Yfh1 and Isu1 were incubated with BS3 cross-linker and analyzed as above. A, chromatograms of [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex without and with BS3 treatment. B and C, SDS-PAGE analysis of size-exclusion chromatography fractions for the uncross-linked (B) and cross-linked (C) complex. D, uncross-linked or cross-linked complex was aerobically loaded with Fe2+, and [2Fe-2S] cluster formation was subsequently measured anaerobically in the presence of 2.5 mm Na2S. Plots shown are the mean ± S.D. of two independent measurements with two different complex preparations. E, assays were performed for the complexes as in D except that 2 mm l-cysteine and 5 μm [Nfs1]·[Isd11] were used to provide elemental sulfur. Each plot represents the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent measurements with two different complex preparations. The reaction with sulfide is started with the addition of sulfide itself, which is immediately available for Fe-S cluster synthesis, whereas the reaction with l-cysteine is started with the addition of [Nfs1]·[Isd11]. The lag observed in the latter reaction is due to the time needed by Nfs1 to generate sufficient elemental sulfur from l-cysteine to support Fe-S cluster synthesis.

To assess the suitability of using chemical cross-linking to probe the complex structure, fractions comprising the ∼330-kDa peak (fractions 52–56) were pooled and incubated with a non-hydrolysable cross-linker, BS3, and then re-purified by size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. 1, A and C). The chromatogram showed one peak with apparent molecular mass of ∼360 kDa (measured at the center of the peak; i.e. fraction 52), and SDS-PAGE revealed a single band that migrated in the high molecular mass region of the gel, although only traces of the Yfh1 and Isu1 bands were visible in the 14–21-kDa region, consistent with the presence of an almost completely cross-linked [Yfh1]n·[Isu1]n complex. The cross-linked [Yfh1]n·[Isu1]n complex was able to catalyze Fe-S cluster formation using either Na2S or l-cysteine in the presence of [Nfs1]·[Isd11] as the source of elemental sulfur with similar rates as the uncross-linked complex (Fig. 1, D and E). As analyzed by dynamic light scattering, the Rh of the uncross-linked (fraction 53) and cross-linked (fraction 52) molecules were 7.2 ± 0.2 and 8.6 ± 1.0 nm, respectively, and both samples exhibited unimodal distribution (Fig. 2A and not shown for the cross-linked complex). The apparently larger molecular mass and Rh of the cross-linked complex probably resulted from coating of the complex surface with cross-linker.

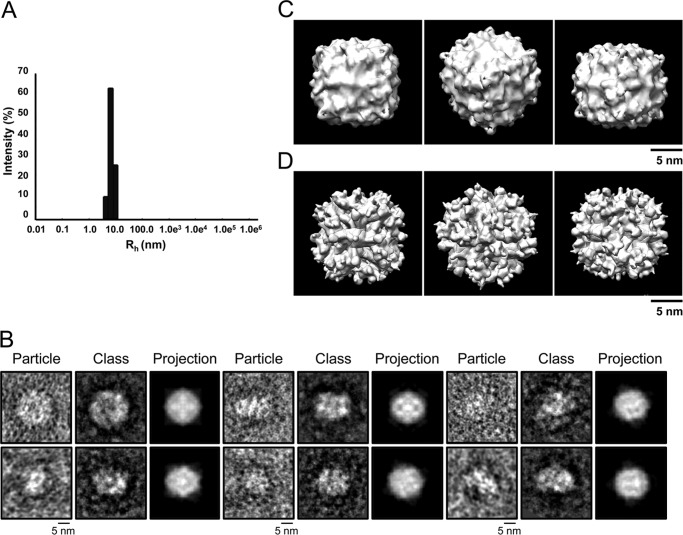

FIGURE 2.

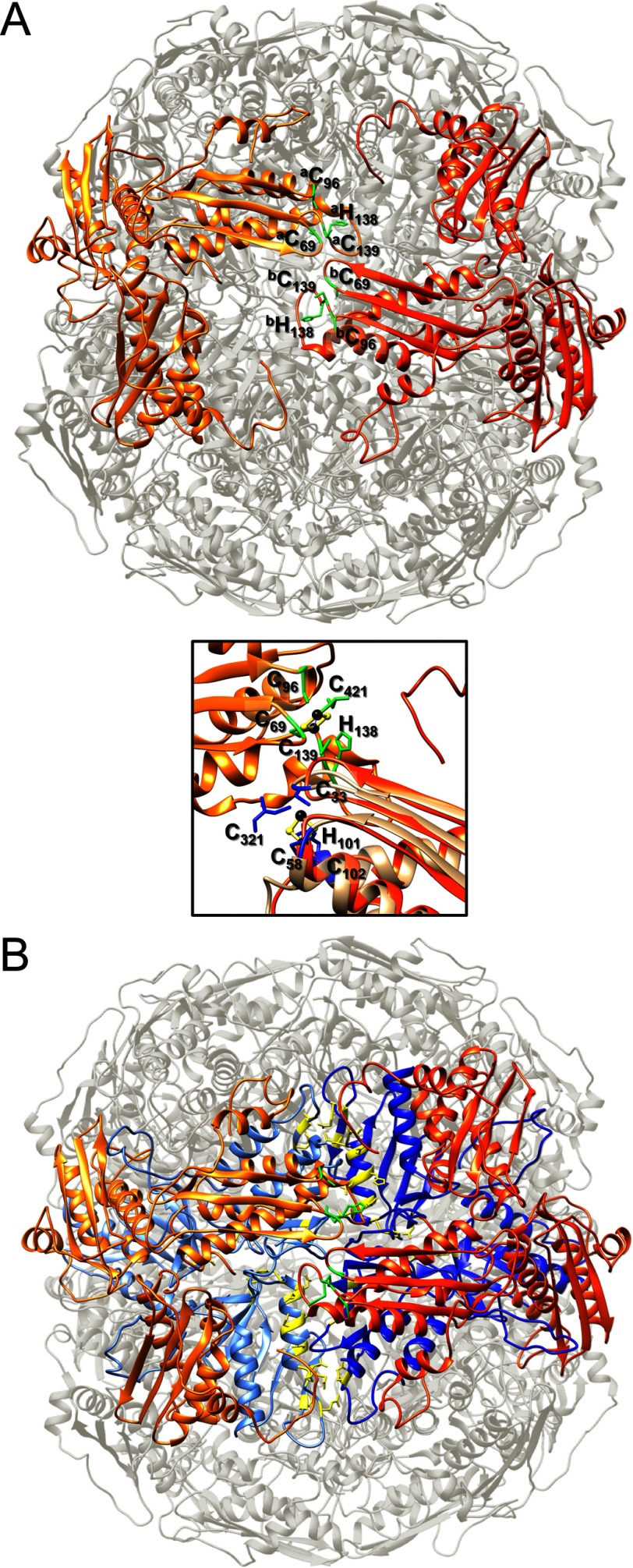

Transmission EM and single particle analysis of S. cerevisiae [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex. A, dynamic light scattering measurements were performed on fraction 53 and the hydrodynamic radius (Rh) was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, electron micrographs of purified uranyl acetate-stained complex particles were obtained and images processed with the EMAN2 software package. Shown is a gallery of class averages, with one representative particle from each class and the corresponding projection of the initial three-dimensional reconstruction shown in C. C, initial model was generated using the best 539 particles identified on electron micrographs with imposed 4, 3, 2 symmetry. D, refined model was subsequently generated using a larger set of 4453 particles. Shown are the 4-, 3-, and 2-fold axes of the models.

EM Single-particle Reconstruction of the [Yfh1]n·[Isu1]n Complex

In uranyl acetate-stained preparations of fraction 53, uncross-linked [Yfh1]n·[Isu1]n complex was visible as roughly globular shapes ∼14 nm in length as well as slightly more elongated shapes ∼16 nm in length (Fig. 2B). These dimensions were consistent with the Rh of ∼7 nm measured by dynamic light scattering analysis of fraction 53 (Fig. 2A), suggesting that we were observing different orientations of an overall homogeneous population of particles. We selected ∼4150 particles from 559 images and used different sets of ∼1400 and ∼530 best particles to generate reference-free class averages using the EMAN2 software package (Fig. 2B and data not shown) (40). In each set of class averages, there were different recurring shapes (Fig. 2B and data not shown) suggesting that [Yfh1]n·[Isu1]n adsorbed to the carbon film of the EM grids with different orientations. In a previous negative staining EM and single particle analysis of the apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer, three-dimensional refinement yielded a model of roughly cubic shape with one Yfh1 trimer at each of its eight vertices (25). This earlier observation and the fact that Yfh1 and Isu1 were present in the [Yfh1]n·[Isu1]n complex with ∼1:1 stoichiometry led us to hypothesize that Isu1 might bind on top of the eight trimers that constitute the apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer (25), resulting once again in a complex of roughly cubic shape. Therefore, several initial three-dimensional reconstructions were generated from the class averages with imposed 4, 3, 2 symmetry, yielding models that consistently exhibited cubic shape (Fig. 2C and not shown). Refinement of initial three-dimensional reconstructions using the best particle sets or the larger set of ∼4150 particles yielded models of similar cubic shape (Fig. 2D and not shown). We then attempted docking of Yfh1 and Isu1 structures into the EM density maps of a few refined models, and based on the quality of the fitting, we selected the model shown in Fig. 2D for further analysis. When this model was further refined against the large set of ∼4150 particles without imposed symmetry, cubic symmetry was maintained with only minor distortion after 4 cycles of refinement (data not shown). The resolution of the model was 17.4 Å as determined by the EMAN 2.07 gold standard (55). The 4-fold axis of the model was 140 Å and the 3-fold axis was ∼160 Å (Fig. 2D), consistent with the dimensions of the particles used to generate the class averages.

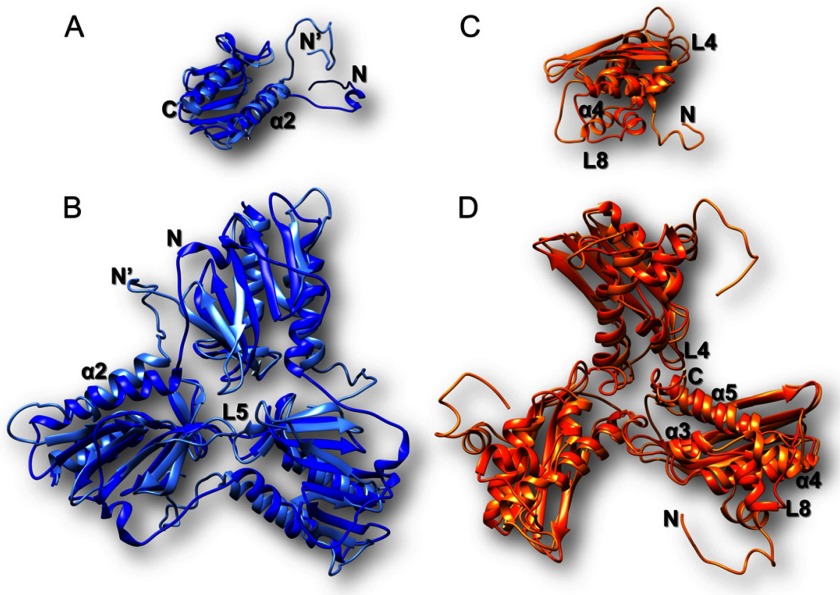

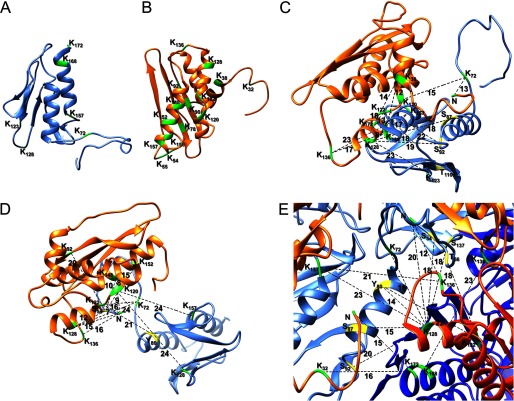

It has been shown that EM density maps with resolution between 3.3 and 35 Å are suitable to attempt docking of protein structures (45, 56, 57). We therefore attempted docking of Yfh1 and Isu1 structures in the EM map of the refined three-dimensional model. The EM density map of the three-dimensional model segmented by the program Chimera (41) revealed 8 volumes with similar shape to the crystal structure of Yfh1Y73A trimer (30) (PDB code 3OEQ) around the 3-fold symmetry axes. Trimeric Yfh1Y73A atomic coordinates were docked into these volumes. The Yfh1Y73A structure could be fitted with a cross-correlation coefficient of 0.70. The nearby remaining segmented density of the three-dimensional model revealed volumes with similar shape to known IscU-family monomers. Several available IscU monomer structures were docked into these volumes, including those from E. coli (PDB code 2KQK, 71.8% sequence identity to Isu1), Aquifex aeolicus (PDB code 2Z7E, 48.8% sequence identity to Isu1), and H. influenzae (PDB code 1R9P, 72.6% sequence identity to Isu1) with reasonable cross-correlation coefficients (data not shown). Therefore, a homology model of Isu1 monomer was generated with I-TASSER, and docking with a cross-correlation coefficient of 0.57 was obtained after removal of the flexible N-terminal region (residues 28–61 of Isu1) (data not shown). This N-terminally deleted Isu1 model was then docked into 23 other similar volumes present in the EM map of the three-dimensional model. Next, guided by cross-linking distances (described in detail below), the N terminus of Yfh1 (residues 52–74) was re-positioned (Fig. 3, A and B). In addition, helix α3, loop L8, and helix α4 of Isu1 were re-positioned, and the Isu1 N terminus was modeled on top of the Isu1 monomer (Fig. 3, C and D). Then, the entire docked structure of the complex (hereinafter designated [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24) was subjected to mild simulation using Molecular Dynamics Flexible Fitting (44, 45) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The simulation improved the fitting of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex into the EM density map, as the cross-correlation coefficient improved from 0.50 to 0.70. After the simulation, the fold of the Yfh1 monomer (Fig. 3A) and the overall arrangement of monomers in the Yfh1 trimer (Fig. 3B) remained very similar to those in the docked structure (30) (PDB code 3OEQ), except for the N terminus that had been manually modeled and showed a new configuration (Fig. 3, A and B). Likewise, the fold of the Isu1 monomer matched the initial docked structure closely except for the presence of the added N terminus and for a small movement of loop L8 and helix α4 (Fig. 3, C and D). All changes satisfied cross-linking distances (see below for details) and resolved stereochemical problems that were present in the docked structure (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Molecular dynamics flexible fitting for docked Yfh1 and Isu1 structures. The EM map of the refined three-dimensional model shown in Fig. 2D was segmented using Chimera. The crystal structure of Yfh1Y73A trimer (PDB code 3OEQ) and a homology model of Isu1 without the N terminus were docked into their respective volumes. Then the N terminus of Yfh1 was repositioned, and the N terminus of Isu1 was modeled based on cross-linking data. The EM map was converted to Situs format to allow rigid-body docking of the entire [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex structure, followed by molecular dynamics simulations and energy minimizations using nanoscale molecular dynamics as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Shown are one Yfh1 monomer (A) and one Yfh1 trimer (B) before (blue ribbon; N indicates the N-terminal region) and after (light blue ribbon; N′ indicates the N-terminal region) molecular dynamics simulations and energy minimizations. Also shown are one Isu1 monomer (C) and one Isu1 trimer (D) before (orange ribbon) and after (light orange ribbon; N indicates the modeled N-terminal region) molecular dynamics simulations and energy minimizations.

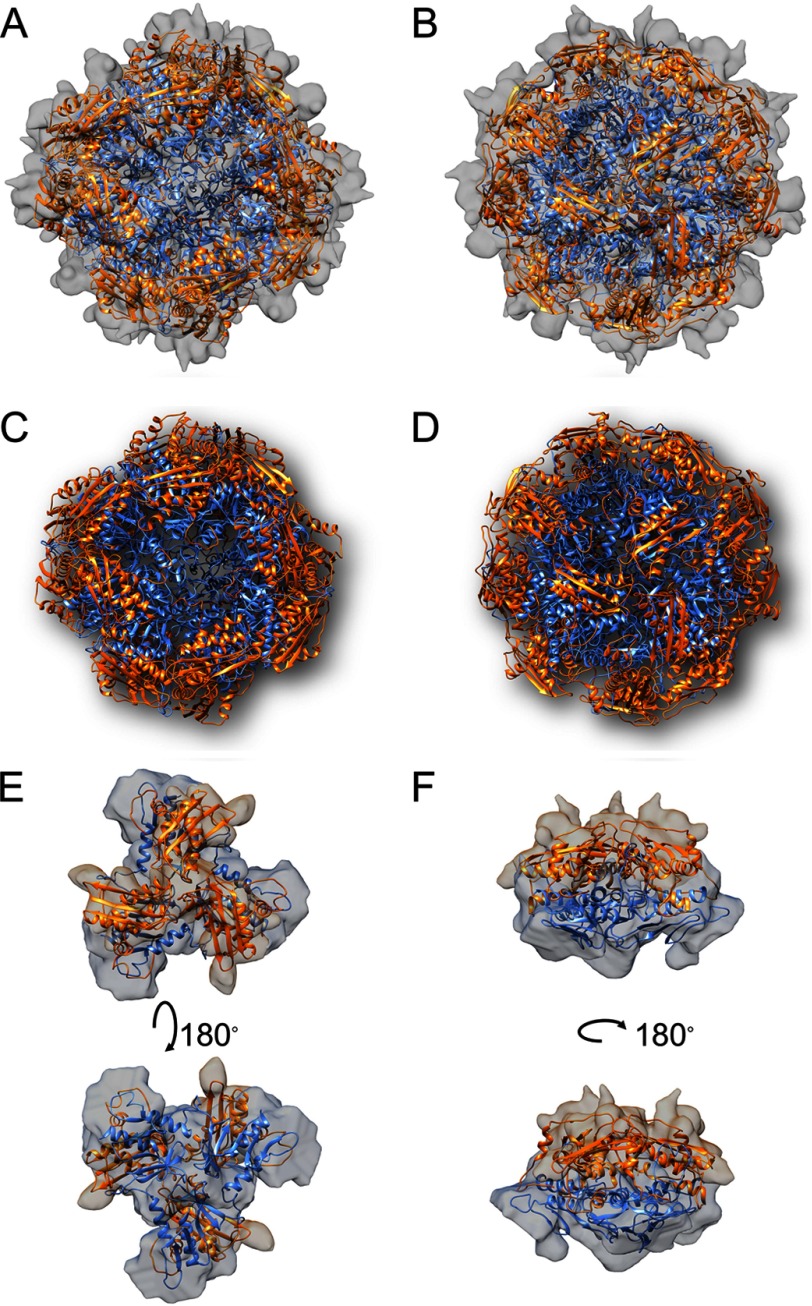

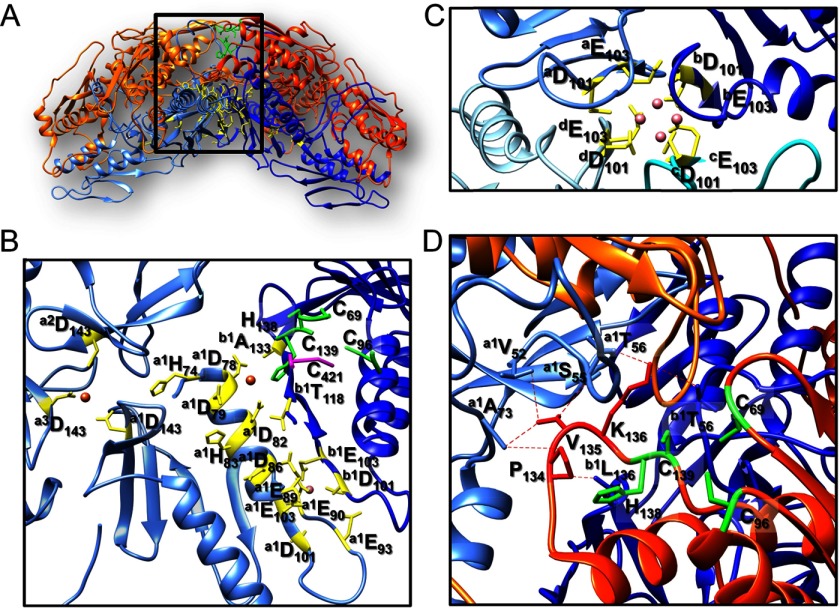

Overall Architecture of the S. cerevisiae [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 Complex

The simulated structure of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex comprises 24 subunits of Yfh1 organized into eight symmetric trimers similar to the previously reported structure of the apo- and holo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mers (25, 31). In addition, 24 Isu1 subunits form eight symmetrical trimers bound on top of the eight Yfh1 trimers, and thus the complex consists of eight [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes (Fig. 4, A–D). The complex has a roughly cubic shape with one [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex at each of its eight vertices (Figs. 2D, middle, and 4, B and D). Each 4-fold axis passes through the centers of two opposite pores delimited by four different [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes (Fig. 4, A and C), while each 3-fold axis passes through the centers of two opposite [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes (Fig. 4, B and D). In each [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex, there are three [Yfh1]·[Isu1] heterodimers in which one Isu1 monomer is positioned on top of one Yfh1 monomer with an ∼5° rotation clockwise with respect to the Yfh1 main axis (Fig. 4, E and F). Although at the current resolution of the three-dimensional model it is not possible to see whether an open channel is present at the 3-fold axis, the arrangement of monomers in each Isu1 trimer appears to create a channel at the 3-fold axis defined by the C terminus and loop L4 of each subunit (Figs. 3D and 4E). The channel at the 3-fold axis of the Isu1 trimer structure is aligned with the channel at the 3-fold axis of the Yfh1 trimer structure directly underneath (Fig. 4E), which was previously shown to coordinate one atom of iron (25).

FIGURE 4.

Overall architecture of the S. cerevisiae [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex. A and B, EM map of the model shown in Fig. 2D with the simulated and energy-minimized structures of 24 Isu1 (light orange ribbon) and 24 Yfh1 (light blue ribbon) subunits assembled within eight [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes. Shown are the 4-fold (A) and 3-fold (B) axes of the complex. C and D as in A and B with EM map removed. E and F, one [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex viewed from the top (E) or the side (F) at different orientations.

Cross-linking Analysis of [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 Complex

We used cross-linking as an independent means to infer information about Yfh1 and Isu1 conformations and protein-protein interactions (58). The cross-linked [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex was enzymatically active (Fig. 1, D and E); hence, it was suitable to obtain functionally relevant structural information. We identified 34 Yfh1-Isu1, 29 Yfh1-Yfh1, and 7 Isu1-Isu1 cross-linked peptides with FDR ≤5%, which provided distance restraints to support the three-dimensional structure of the complex (Table 1 and supplemental Table S1). We measured the actual distances between cross-linked residues before and after simulation of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 structure. In several instances, distances measured within the simulated structure (outside of the Yfh1 and Isu1 regions that had been manually modeled) were more consistent with the distance restraints as compared with distances measured within or between the docked structures (data not shown). This confirmed that some rearrangements of Yfh1 and Isu1 had occurred during complex formation and that simulation of the entire [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 structure improved the model.

When using the distance constraints described in the legend of supplemental Table S1 (see also “Experimental Procedures” for an explanation of how these constraints are calculated), our simulated structure is in agreement with 58/70 or 83% of the cross-linked peptides identified (Table 1). When using the maximum allowable distance constraints described in the legend of supplemental Table S1 (see also “Experimental Procedures” for an explanation of how these constraints are calculated), the agreement increases to 100% (Table 1). This was established by measuring, in the entire [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 structure, the distances between all possible pairs of cross-linked residues within any given cross-linked peptide (supplemental Table S1) and by identifying mean distances equal to or lower than the distance constraints (highlighted in light gray in supplemental Table S1), equal to or lower than the maximum allowable distance constraints (highlighted in dark gray in supplemental Table S1), and greater than the maximum allowable distance constraints (highlighted in yellow in supplemental Table S1). Agreement between the simulated structure and any given cross-linked peptide was established if at least one of the mean distances measured in the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 structure was within the distance constraints or the maximum allowable distance constraints (Table 1 and supplemental Table S1).

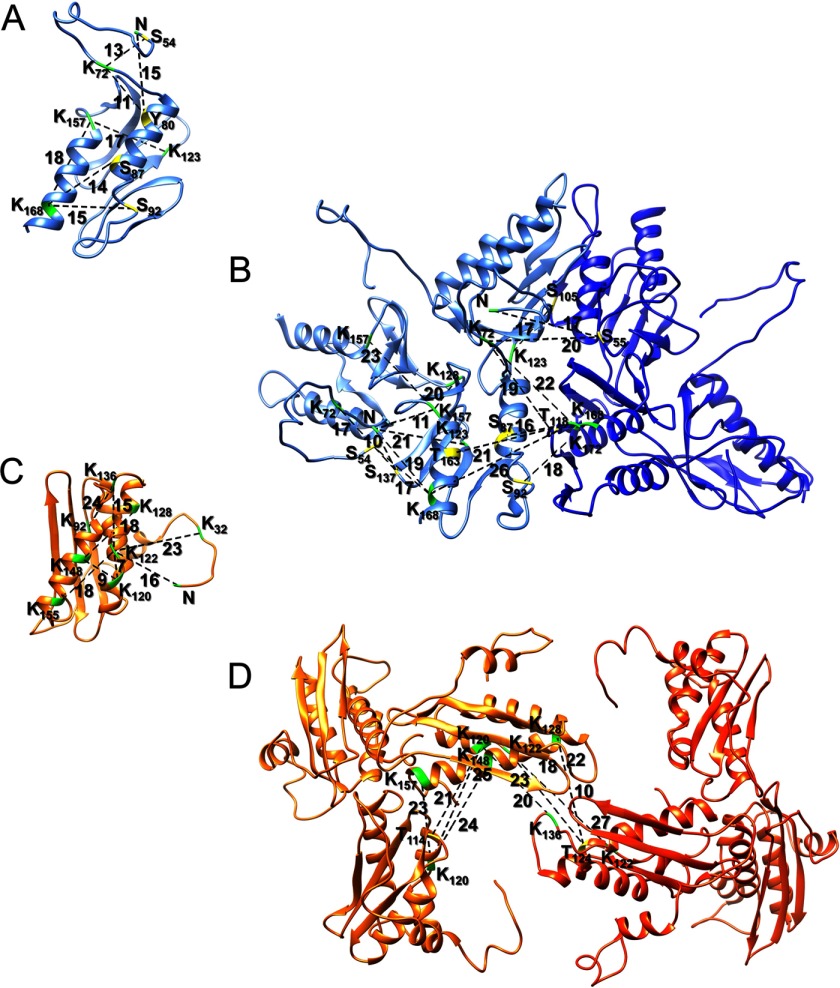

The identified cross-links involve all six Lys residues of Yfh1 and all 15 Lys residues of Isu1 (shown in Fig. 5, A and B), as well as the N-terminal amino groups and several Ser, Thr, and Tyr residues of both Yfh1 and Isu1, most of which are widely separated in the primary sequence of each protein. Based on general guidelines for this type of analysis (58), the large number of identified cross-links between Yfh1 and Isu1 as well as within Yfh1 or within Isu1 supported a tight binding complex. Next, mapping of the cross-links in the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex structure revealed that the structure fulfilled the distance constraints obtained from the cross-linking analysis at nine different protein-protein interaction levels, i.e. between Yfh1 and Isu1 subunits of the same Yfh1-Isu1 heterodimer (Fig. 5C and supplemental Table S1a), between Yfh1 and Isu1 subunits of the same [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex (Fig. 5D and supplemental Table S1a), between Yfh1 and Isu1 subunits of two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes (Fig. 5E and supplemental Table S1a), within individual Yfh1 or Isu1 subunits (Fig. 6, A and C, and supplemental Tables S1, b and c), between Yfh1 or Isu1 subunits of the same [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex (Fig. 6, B and D, and supplemental Tables S1, b and c), and between Yfh1 or Isu1 subunits of two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes (Fig. 6, B and D, and supplemental Tables S1, b and c). Specifically, several cross-links were identified between the N terminus of Yfh1 (both the N-terminal amino group and Lys-72) and the following regions of Isu1 (Fig. 5, C–E): (i) N terminus (N-terminal amino group, Lys-32 and/or Lys-38); (ii) β-sheet 2 (Lys-78) and β-sheet 3 (Lys-90 and/or Lys-92); (iii) helix α3 (Lys-120 and/or Lys-122); helix α4 (Lys-128), and C-terminal helix α5 (Lys-148, Lys-152, Lys-155, and/or Lys-157). Additional cross-links were identified between Yfh1 loop L5 (Lys-123 and/or Lys-128) and helix α3 and α4 (Lys-120, Lys-122, and Lys-128) of Isu1. Finally, the C terminus of Yfh1 (Lys-168 and/or Lys-172) formed cross-links with the N terminus (N-terminal amino group, Lys-32, and/or Lys-38) as well as helix α3 (Lys-120 and/or Lys-122) and helix α4 (Lys-128) of Isu1. Similarly, Lys-157, at the beginning of helix α2 of Yfh1, formed cross-links with helix α3 (Lys-120 and/or Lys-122) and helix α4 (Lys-128) of Isu1. Based on actual mean distances measured between all possible pairs of cross-linked residues, some cross-links appeared possible within one [Yfh1]·[Isu1] heterodimer (supplemental Table S1a, pp. 6–8 and 10–14; Fig. 5C) and also between two heterodimers within the same [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex (supplemental Table S1a, pp. 1–7 and 10; Fig. 5D) and between two adjacent sub-complexes (supplemental Table S1a, pp. 1, 4, 6–8, and 10–14; Fig. 5E). In contrast, the cross-link between the Yfh1 N terminus and Lys-128 of Isu1 only appeared possible in the latter two instances (supplemental Table S1a, p. 1; Fig. 5, D and E).

FIGURE 5.

Architecture of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex analyzed using primary amine specific cross-linking. The [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex was subjected to chemical cross-linking, limited proteolysis, and MS/MS analysis, after which the program StavroX 3.5.1 was used to generate a list of cross-linked peptides with FDR ≤5%, as described under “Experimental Procedures” and as shown in Table 1 and supplemental Table S1. A and B, lysine residues (K) available for cross-linking with BS3 in each Yfh1 (A) and Isu1 (B) monomer. Dotted lines show representative cross-links within one [Yfh1]·[Isu1] heterodimer (C), between two adjacent Yfh1 and Isu1 subunits of the same [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex (D), and between Yfh1 and Isu1 subunits of two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes (E). In the two sub-complexes, Yfh1 is shown as light blue or blue ribbon and Isu1 as light orange or orange ribbon. Lys residues are shown in green and non-Lys residues in yellow. Numbers are the average protein-protein distances measured between each pair of cross-linked residues in the entire [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 structure (see supplemental Table S1 for additional details).

FIGURE 6.

Architecture of the Yfh1 and Isu1 trimers analyzed using primary amine-specific cross-linking. Cross-linking data were obtained as described in the legend of Fig. 5. Dotted lines show representative cross-links within one Yfh1 subunit (A), between Yfh1 subunits of the same trimer or two adjacent trimers (shown as blue and light blue ribbons) (B), within one Isu1 subunit (C), and between Isu1 subunits of the same trimer or two adjacent trimers (shown as orange and light orange ribbons) (D). Lys residues are shown in green and non-Lys residues in yellow. Numbers are the average protein-protein distances measured between each pair of cross-linked residues in the entire [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 structure (see supplemental Table S1 for additional details).

Yfh1-Yfh1 cross-links formed between the N terminus (both the N-terminal amino group and Lys-72) and other regions of the protein, including loop L5 (Lys-123 and/or Lys-128) close to the β-sheet, and helix α2 at the C terminus (Lys-157, Lys-168, and/or Lys-172). There were also cross-links between the C terminus (Lys-168 and/or Lys-172) and loop L5 (Lys-123 and/or Lys-128). Some of these Yfh1-Yfh1 cross-links could have formed not only within the same monomer but also between two monomers of the same trimer (N terminus–Lys-72; N terminus–Lys-123 and/or Lys-128; N terminus–Lys-157; Lys-72– Lys-128) or between two monomers from adjacent trimers (N terminus–Lys-168/Lys-172; Lys-72–Lys-168/Lys-172; Lys-168–Lys-157) (supplemental Table S1b, pp. 1–5; some of these cross-links are shown in Fig. 6, A and B). Based on actual mean distances measured between all possible pairs of cross-linked residues, some cross-links were more likely to have formed between subunits of the same Yfh1 trimer or between two Yfh1 trimers (supplemental Table S1b; Fig. 6B). For example, cross-links between the N terminus and loop L5 (Lys-123 and/or Lys-128) or C-terminal helix α2 (Lys-157 and Lys-168) were more probable between two subunits of the same Yfh1 trimer (supplemental Table S1b, pp. 1–2; Fig. 6B). Moreover, cross-links between the N terminus (Lys-72) and the C terminus (Lys-168 and Lys-172) had most likely formed between subunits of two adjacent trimers (supplemental Table S1b, p. 3; Fig. 6B).

Isu1-Isu1 cross-links formed between Lys residues in helix α3 (Lys-120 and Lys-122) and other regions of the protein, including helix α3 itself (Lys-120 and/or Lys-122), helix α4 (Lys-128), the N-terminal region (Lys-32 and Lys-38), and C-terminal helix α5 (Lys-148, Lys-152, Lys-155, and/or Lys-157). As mentioned above for Yfh1, the symmetrical arrangement of Isu1 monomers and trimers allowed for some Isu1-Isu1 cross-links to be possible within the same monomer (supplemental Table S1c; Fig. 6C), between two monomers of the same trimer (supplemental Table S1c, p. 1–2; Fig. 6D), or between monomers from two adjacent trimers (supplemental Table S1c, p. 3–4; Fig. 6D). However, the Lys-122–Lys-122 cross-link could only have formed between two adjacent trimers (supplemental Table S1c, p. 1; Fig. 6D). Of the five Lys residues in the N-terminal half of Isu1 (Lys-54 and Lys-55 in loop L2, Lys-78 in β-sheet 2, and Lys-90 and Lys-92 in β-sheet 3), Lys-92 was the most likely to form a cross-link with the highly conserved PVK motif (18) (Lys-136) within the same Isu1 subunit (supplemental Table S1c, p. 4; Fig. 6C), whereas Lys-120 and Lys-122 could form cross-links with Lys-136 both within the same Isu1 subunit and between Isu1 subunits of two adjacent Isu1 trimers (supplemental Table S1c, pp. 3–4; Fig. 6, C and D).

Cross-links were also identified between Lys and non- Lys residues such as tyrosine, threonine, and serine and were consistent with Lys–Lys cross-links (supplemental Table S1 and Figs. 5, C–E, and 6, A–D). Thus, these data together provide distance constraints that support the fold of the Yfh1 and Isu1 monomers and interactions between Yfh1 and/or Isu1 subunits of the same [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex and between subunits of two adjacent sub-complexes.

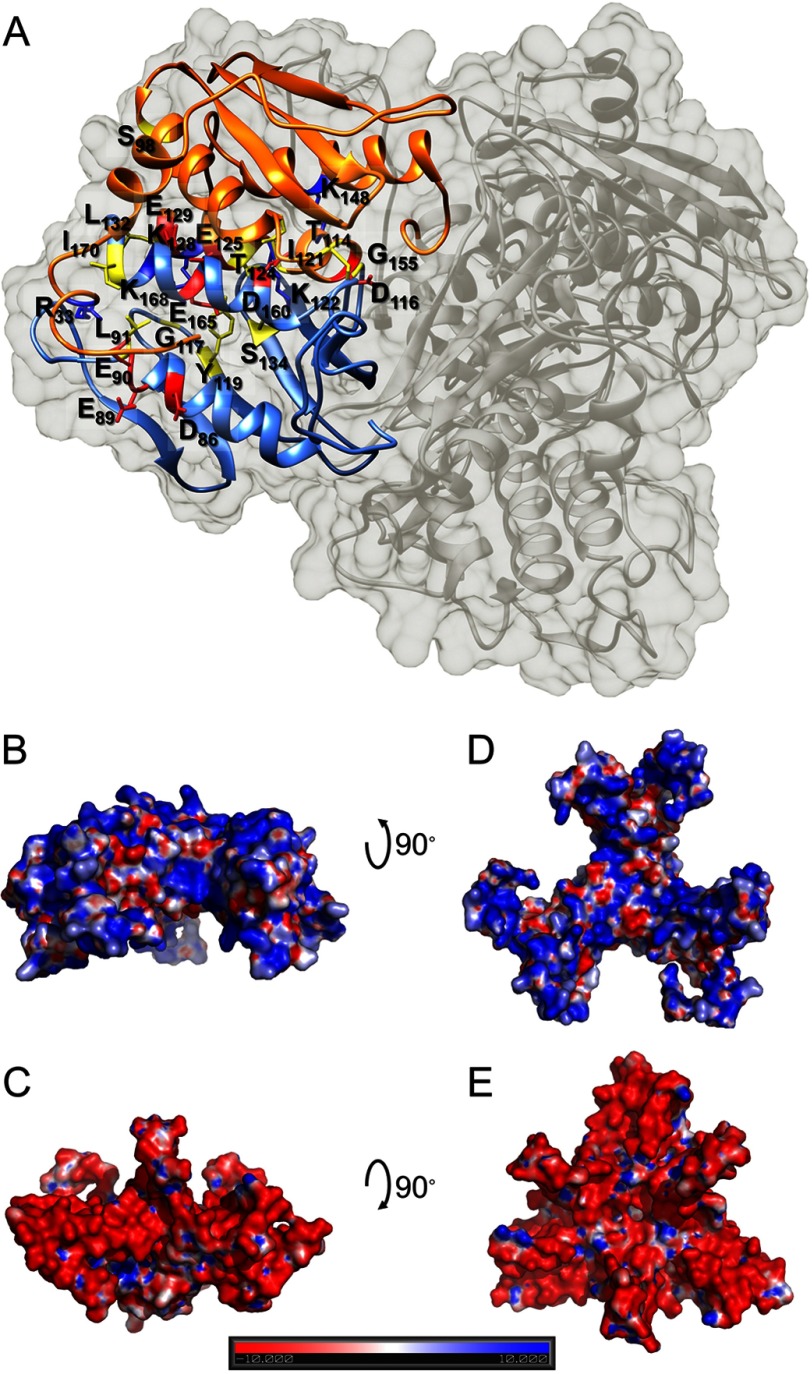

Contact Surfaces of [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 Complex

We used the program PISA (54) to identify possible interfaces between the Yfh1 and Isu1 protein chains present in the complex structure. The program identified seven main recurring interfaces, six present 24 times and one present 12 times in the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex. All seven interfaces are represented within two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes, which therefore represents the structural building block of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex. About 50 residues of Isu1 (including invariant residues Ser-98, Ile-121, Lys-122, Thr-124, Glu-129, Leu-132, and Lys-148 and conserved (in eukaryotes) residues Arg-33, Asp-116, Lys-128, and Glu-129) and about 50 residues of Yfh1 (including conserved (in eukaryotes) residues Asp-86, Glu-89, Glu-90, Leu-91, Gly-117, Tyr-119, Ser-134, Gly-155, Asp-160, Glu-165, Lys-168 and Ile-170) are present in the largest interface with ∼1624 Å2 (average of 24 interfaces) of buried surface area (BSA). Several residues in this interface are predicted to form hydrogen bonds and salt bridges between the two proteins (Fig. 7A). Charge analysis of this interface shows that the Isu1 surface is mostly positively charged, and the Yfh1 surface is mostly negatively charged (Fig. 7, B–E), strongly suggesting that electrostatic interactions may drive complex formation. One additional significantly sized interface is present between one Yfh1 subunit and an adjacent Isu1 subunit within the same [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex with BSA of ∼817 Å2 (average of 24 interfaces). The Yfh1 N terminus (Val-52, Glu-53, Gln-59, Glu-64, and Val-65) and several residues of Isu1 (including invariant residues Cys-69, Thr-124, and Glu-144), as well as Asn-146 on the β-sheet surface of Yfh1 and Ser-165 at the C terminus of Isu1 together contribute to this interface (Fig. 8A). In addition, the Yfh1 N terminus (Thr-56 and Asp-57) interacts also with a subunit of Isu1 (invariant residues His-138, Cys-139, Val-135, and Lys-136) from an adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex, with BSA of ∼397 Å2 (average of 24 interfaces) (Fig. 8B). These two interfaces show how involved the Yfh1 N terminus is in stabilizing Yfh1-Isu1 interactions, both within the same sub-complex and between two adjacent sub-complexes. The Yfh1 N-terminal interfacial location is consistent with cross-linking data (Fig. 6, A and B). Although the Yfh1 N terminus is not conserved, the interacting residues of Isu1 are invariant from E. coli to human.

FIGURE 7.

Interface of the [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex. A, PISA-identified Yfh1-Isu1 heterodimer interface. Conserved residues within this interface predicted to form hydrogen bonds and salt bridges between the two proteins are shown as red, blue, and yellow sticks for acidic, basic and neutral residues. B–E, electrostatic potential of the entire [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex interface generated using PyMOL. B and C, Isu1 trimer (B) and Yfh1 trimer (C) are shown in a lock and key arrangement; D and E, inside view of the interface between Isu1 trimer (D) and Yfh1 trimer (E). Increasing red represents increasing negative charge; white is neutral charge; and increasing blue represents increasing positive charge.

FIGURE 8.

Interfaces within two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes. Shown are PISA-identified interfaces between one Yfh1 subunit and an adjacent Isu1 subunit of the same [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex (A); Yfh1 N terminus of one [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex and one Isu1 subunit of the adjacent sub-complex (B); Isu1 subunits of the same or adjacent sub-complexes (C and D); and Yfh1 subunits of the same or adjacent sub-complexes (E and F). Residues are shown as red, blue, and yellow sticks for acidic, basic and neutral residues.

As for Isu1-Isu1 interactions, there is an interface with BSA of ∼478 Å2 (average of 24 interfaces) formed by Isu1 subunits of the same trimer around the 3-fold axis that is mediated by hydrogen bonds between residues in the C terminus of each subunit (Asn-159–Asp-81, Thr-160/162–Thr-160, Ser-165–Asp-116, and Ser-156–Arg-158) (Fig. 8C). An interface with BSA of ∼127 Å2 (average of 12 interfaces) between two Isu1 subunits of adjacent Isu1 trimers is formed via interactions between residues Lys-136–Val-135 and Leu-137– Lys-136 (Fig. 8D), which are part of the highly conserved PVK motif of Isu1 (18).

Previously described Yfh1-Yfh1 interactions were also identified. The first is an interface with BSA of ∼674 Å2 (average of 24 interfaces) between the N terminus of one subunit of the trimer (Val-52, Glu-53, Ser-55, and Glu-76) and the β-sheet surface of an adjacent subunit (Leu-136, Asn-140, Arg-141, Leu-152, Arg-153, and Asn-154); hydrogen bonding between the conserved Asn-127 of one subunit and the invariant Gln-129 of the other subunit contributes to this interface (Fig. 8E), which was shown to be important for trimer stabilization (25). The second is an interface with BSA of ∼694 Å2 (average of 24 interfaces) between two adjacent trimers and involves the ferroxidation and mineralization sites of two Yfh1 subunits (Asp-82, Asp-86, Glu-93, and Asp-101) along with conserved residues Val-102, Leu-104, Ser-105, and Ile-113 on one subunit and Glu-89, Ser-92, Gly-117, and Thr-118 on the other subunit (Fig. 8F). This surface was previously described in the context of the Yfh1 hexamer structure (22), in which one atom of iron was coordinated by Thr-118 and Ala-133 from the first trimer and by an acidic surface contributed by the second trimer, including highly conserved residues Glu-93 and Asp-101 (22).

These results together with cross-linking results indicate that each [Yfh1]·[Isu1] heterodimer is stabilized by interactions between the Yfh1 N terminus and helix α3 and α4 of Isu1 as well by interactions between the C terminus of Yfh1 and the N terminus of Isu1 (Figs. 5C and 7A). Moreover, the [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex is stabilized by interactions between adjacent [Yfh1]·[Isu1] heterodimers. Specifically, the Yfh1 N terminus from one heterodimer extends toward the adjacent heterodimer to interact with helix α3, α4, and α5 of Isu1 and with the β-sheet of Yfh1 (Figs. 5D and 8A). The same regions are also involved in the stabilization of adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes (Figs. 5E and 8B).

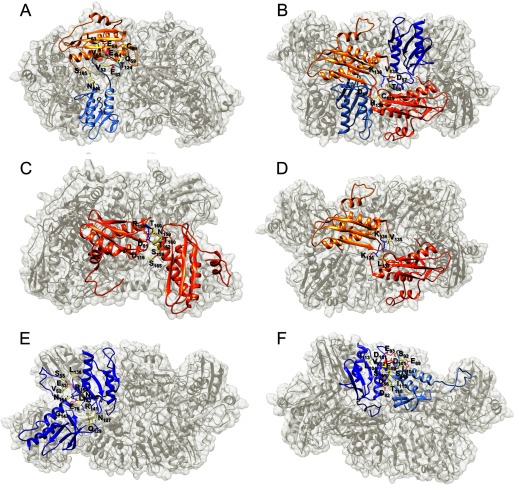

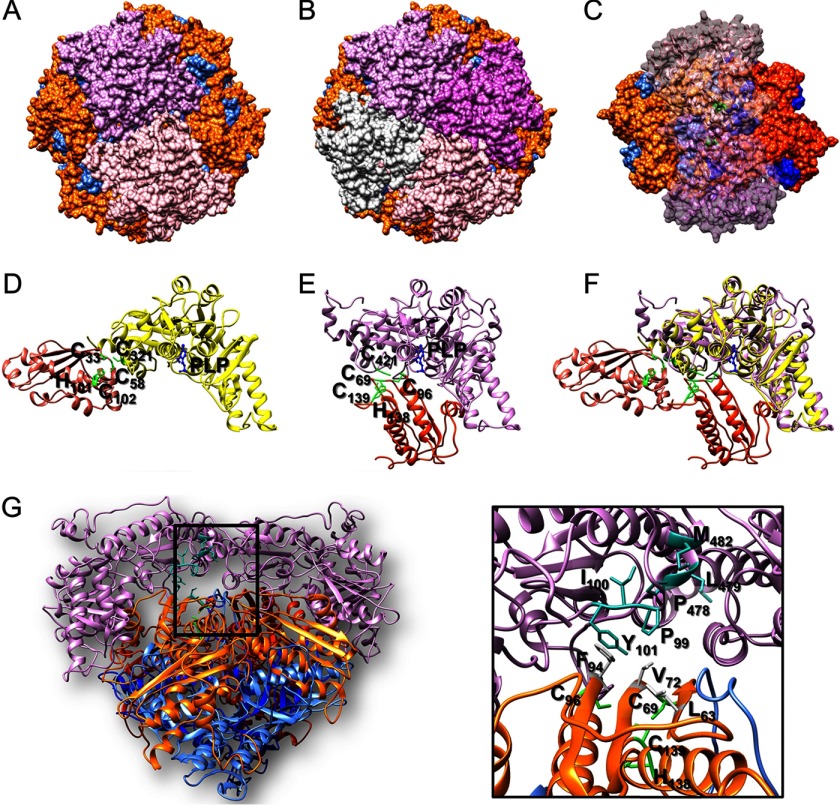

Proposed [2Fe-2S] Cluster Assembly Site of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 Complex

Two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes are present at each of the 2-fold axes of the complex (Fig. 9, A and B). Two Isu1 subunits, one from each [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex, face each other with their respective [2Fe-2S] coordinating sites formed by the invariant Cys-69, Cys-96, Cys-139, and His-138 residues, known to be involved in Fe-S cluster coordination (Fig. 9A) (15, 33, 34). In each site, these residues are within ∼2–4 Å from each other, in a manner that appears suitable to coordinate one [2Fe-2S] cluster (Fig. 9A, inset) (15). Each [2Fe-2S] cluster-coordinating site is close to conserved residues of Yfh1 known to be involved in iron binding (Fig. 9B) (22, 59). Three putative iron coordinating sites of Yfh1 were identified and modeled after aligning the structures of iron-bound Yfh1Y73A trimer (PDB codes 2FQL and 4EC2) and cobalt-bound CyaY monomer (PDB code 2EFF) (Fig. 10, A–C) (25, 30, 60). One of the three iron-binding sites is in the 3-fold channel of the Yfh1 trimer opposite the [2Fe-2S] site, while the other two sites are contributed by residues from two adjacent Yfh1 trimers (Fig. 10, A and B). This suggests that two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes represent not only the structural building block but also the minimal functional unit of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex.

FIGURE 9.

Proposed [2Fe-2S] cluster assembly site. A, top view of two Fe-S cluster assembly sites formed by two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes at the 2-fold axis of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex. Isu1 trimers are shown as light orange and orange ribbons with Fe-S cluster-coordinating residues shown as green sticks. The letters a and b denote two adjacent Isu1 trimers. The distance between the backbone α-carbons of each pair of Cys-69 and Cys-139 residues in the entire structure correspond to 11.8 ± 1.0 and 12.9 ± 1.8 Å, respectively (n = 12). In the inset (bottom right), one of the two Isu1 cluster assembly sites shown in A is aligned with IscU (shown as a tan ribbon) from the crystal structure of the A. fulgidus [IscS]2·[IscU]2 complex. IscU residues and Cys-321 of IscS (shown as blue sticks) coordinate a [2Fe-2S] cluster (iron and sulfur atoms shown as black and yellow spheres). By analogy, a [2Fe-2S] cluster was modeled inside the site formed by Isu1 coordinating residues and Cys-421 of Nfs1 (shown as green sticks) (top left). B, as in A with Yfh1 trimers shown as light blue and blue ribbons with iron coordinating residues shown as yellow sticks.

FIGURE 10.

Proposed path for iron delivery from Yfh1 to Isu1. A, side view of the proposed Fe-S cluster assembly site formed by two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes. Color code is as in Fig. 9. B, three potential iron-binding sites were identified through alignment of our complex structure with the structures of iron-bound Yfh1Y73A trimer (PDB codes 2FQL and 4EC2) and cobalt-bound CyaY monomer (PDB code 2EFF). The letters a and b denote two adjacent Yfh1 trimers; the numbers 1–3 denote different subunits of trimer a and trimer b. For Isu1, only the Fe-S cluster-coordinating residues are shown as green sticks. For Nfs1, only the catalytic Cys-421 is shown as a magenta stick. C, putative mineralization site at the 4-fold axis of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex formed by four Yfh1 monomers that belong to four different [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes. Iron atoms were modeled through alignment of our complex structure with the structures of cobalt-bound CyaY monomer as described in B. The letters a–d denote four adjacent Yfh1 trimers. D, Isu1 flexible loop that contains the PVK motif is shown in red, with Pro-134, Val-135, and Lys-136 as red sticks and nearby Fe-S cluster-coordinating residues as green sticks. Dotted lines show potential hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions between the PVK motif and residues from the two Yfh1 trimers that form the iron-donation path shown in B. The letters a and b denote two adjacent Yfh1 trimers; the numbers 1 and 2 denote different subunits of trimer a and trimer b.

The PVK motif (Pro-134, Val-135, and Lya-136) of Isu1, which is important for Yfh1-Isu1 interactions in yeast (18), is close to the Fe-S cluster assembly site and may interact with both the Yfh1 subunit immediately underneath (i.e. in the same [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex) as well as the adjacent Yfh1 subunit from the opposite [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex (Fig. 10D). Moreover, PISA analysis predicts hydrogen bonding between the two opposite Isu1 subunits involving Lys-136–Val-135 and Leu-137–Lys-136. These interactions may contribute to the stability of the cluster assembly site.

Four Nfs1 monomers were docked inside four symmetrical pockets at the 4-fold axis of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex using Chimera (Fig. 11, A and B). This docking results in the presence of a symmetric Nfs1 dimer lying on top of two [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes (Fig. 11C). The docking of each Nfs1 monomer was guided by the position of the Isu1 Fe-S cluster coordination site, which in the A. fulgidus [IscS]2·[IscU]2 structure is close to the IscS flexible loop containing the catalytic Cys-321 (Fig. 11D). In our modeled structure of Nfs1, the invariant catalytic Cys-421 (Cys-321 in A. fulgidus IscS) is on a flexible loop ∼8 Å from Cys-139 of Isu1 (Fig. 11E), which in the human system has been proposed to serve as the main acceptor of the persulfide formed on the desulfurase (61). When the A. fulgidus [IscS]2·[IscU]2 structure is aligned with our modeled structure, Nfs1 and IscS overlap each other, whereas Isu1 is rotated 90° relative to IscU on the same plane, which brings the Fe-S cluster coordination site of Isu1 closer to the Nfs1 flexible loop (Fig. 11F).

FIGURE 11.

Proposed mode of Nfs1 binding to the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex. A and B, two and four Nfs1 monomers were docked into two and four symmetric pockets at the 4-fold axis of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex. Nfs1 monomers are shown as plum, orchid, pink, and light gray surfaces. C, docking of Nfs1 results in the presence of a symmetric Nfs1 dimer resting on top of the two putative [2Fe-2S] cluster assembly sites formed by two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes (same as Fig. 9B) in such a manner that the flexible loop of each Nfs1 subunit is inside a small pocket close to the Fe-S cluster coordination site of the corresponding Isu1 subunit (shown as green surface). D, [IscS]·[IscU] sub-complex from the A. fulgidus [IscS]2·[IscU]2 structure (PDB code 4EB5) with IscS and IscU shown as yellow and salmon ribbons, respectively. E, proposed [Nfs1]·[Isu1] sub-complex at the putative [2Fe-2S] cluster assembly site described in C, with Nfs1 and Isu1 shown as plum and orange ribbons, respectively. The flexible loop containing Cys-421 and the substrate-binding site of Nfs1 is shown in relation to the position of the Fe-S cluster-coordinating residues of Isu1. F, alignment of the [Nfs1]·[Isu1] model with the [IscS]·[IscU] structure shows the different positions of IscU and Isu1 relative to the IscS/Nfs1 flexible loop. G, hydrophobic residues of Isu1 (gray sticks) and Nfs1 (sea-green sticks) implicated in potential hydrophobic interactions between the two proteins in proximity of the Fe-S cluster-coordinating residues of Isu1 shown as green sticks. The boxed region is enlarged in the inset.

Hydrophobic residues (Leu-63, Val-72, and Phe-94) of Isu1 were shown to be critical for interaction with hydrophobic residues of Nfs1, Met-482, Pro-478, and Leu-479 (62). In our structure, residues Tyr-101, Ile-100, and Pro-99 also are part of this hydrophobic interaction surface (Fig. 11G). These residues are in close proximity to the proposed Fe-S cluster assembly site (Fig. 11G, inset).

Discussion

Although the iron donor, Yfh1, the sulfur donor, [Nfs1]·[Isd11], and the Fe-S cluster scaffold, Isu1, are well known to work together to ensure the assembly of new Fe-S clusters, the architecture of the complexes and sub-complexes formed by these proteins is not well defined, and an integrated mechanism for the concerted delivery of iron and sulfur to the site of Fe-S cluster assembly is not yet known. To gain insight, we reconstituted and purified a stable, functional complex consisting of stoichiometric amounts of the iron donor, Yfh1, and the Fe-S cluster scaffold, Isu1, and via negative staining EM single-particle analysis obtained a three-dimensional model at a resolution of ∼17 Å. Additional approaches subsequently led to the proposed structure of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex, which independently fulfills two requirements. First, the requirement to fit into the EM density map of the three-dimensional model, which we achieved by segmenting the map and sequentially docking Yfh1Y73A trimers and Isu1 monomers into the available volumes in a manner that, after Molecular Dynamics Flexible Fitting, resulted in a cross-correlation coefficient of 0.70, without steric clashes and consistent with the measured Yfh1:Isu1 stoichiometry of ∼1:1. Second, the proposed complex structure fulfills the distance constraints obtained from the cross-linking analysis at nine different protein-protein interaction levels. In addition, the interfaces involved in cross-links were independently identified by the program PISA as being compatible with the formation of hydrogen bonds and salt bridges, often involving conserved residues of Isu1 and Yfh1. Finally, the proposed structure of the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex is supported by the arrangement of cluster-coordinating residues of Isu1 with respect to iron-binding residues of Yfh1 as well as the possibility to dock Nfs1 on the structure in a manner that recapitulates the known mechanism for sulfur donation from the cysteine desulfurase to the scaffold.

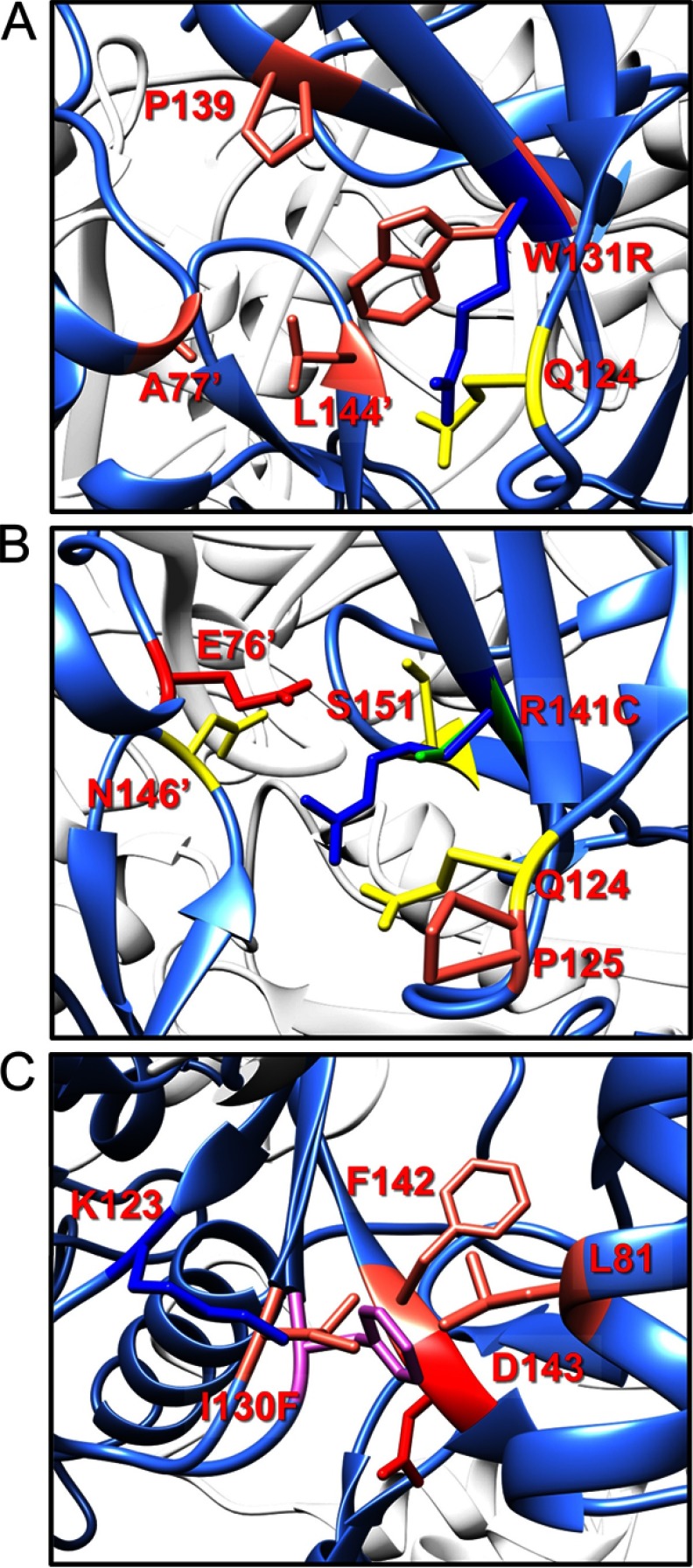

IscU-type scaffolds, including Isu1, have been shown to exist in monomeric or oligomeric states in the absence of protein partners (8, 33–36). Accordingly, by use of small angle x-ray scattering, we have recently determined that at the protein concentration used to assemble the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex purified Isu1 exists as a mixture of monomer (∼30%), dimer (∼50%), and trimer (∼20%).4 However, binding of this distribution of Isu1 to apo-Yfh1Y73A 24-mer drives the formation of eight stable Isu1 trimers in a manner that enables the formation of 24 [2Fe-2S] cluster assembly sites. Similarly, conformational changes leading to stabilization of IscU were observed upon binding of IscU to the co-chaperone HscB (39). These data indicate that binding of IscU/Isu1 to its protein partners may result in new conformations that may be required for the activity of IscU/Isu1 in Fe-S cluster assembly and delivery.

In the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex structure, one symmetric Isu1 trimer binds on top of each of the eight trimers that form the Yfh1Y73A 24-mer such that the complex consists of eight [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes. Two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes are present at each of the 2-fold axes of the complex such that two Isu1 subunits, one from each [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complex, face each other with their respective [2Fe-2S] coordinating sites (Fig. 9A). Each of these sites is close to an iron-binding site formed by known iron-coordinating residues of Yfh1 from the two adjacent Yfh1 trimers (trimer a and trimer b) (Figs. 9B and 10B), suggesting that two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes are the minimal functional unit for iron donation for Fe-S cluster assembly. Modeling further suggests that two subunits of Nfs1 may bind symmetrically on top of two adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3 sub-complexes at the 2-fold axis of the complex (Fig. 11C). Thus, each pair of adjacent [Yfh1]3·[Isu1]3·[Nfs1] sub-complexes creates two putative [2Fe-2S] cluster assembly centers (Fig. 9A, inset) where critical amino acids involved in iron and sulfur donation and coordination are arranged in close proximity as would be required for the safe handling of potentially toxic iron and sulfur atoms.

The mechanism underlying sulfur donation has been described previously in the context of the crystal structure of the E. coli [IscS]·[IscU] and the A. fulgidus [IscS]2·[IscU]2 complexes (PDB codes 3LVL and 4EB5) (14, 15) and further in the context of the yeast [Nfs1]2·[Isd11]2·[Isu1]2·[Yfh1]2 complex (12, 17). Based on these studies, two conformational changes are thought to take place in Nfs1 for sulfur donation to Isu1. First, Yfh1 binding exposes the Nfs1 PLP cofactor so that a PLP-cysteine adduct may form. Second, Isd11 induces a conformational change in Nfs1 to bring a flexible loop (involving residues 410–429) close to the PLP-cysteine adduct (closed conformation), allowing the transfer of sulfur from the adduct to Cys-421 within the loop. It is also thought that a further ∼20 Å displacement of the Nfs1 flexible loop would be required to move the persulfurated Cys-421 close to the Fe-S cluster assembly site (extended conformation) to enable sulfur transfer to Isu1 (17). Our structure is consistent with this mechanism. Upon docking of the Nfs1 model into the [Yfh1]24·[Isu1]24 complex structure, Cys-421 of Nfs1 is at ∼11 Å from the PLP and at ∼8 Å from Cys-139 of Isu1, which in the human system has been proposed to serve as the initial or main acceptor of the persulfide formed on the desulfurase (61). Alignment of the A. fulgidus [IscS]2·[IscU]2 structure (PDB code 4EB5) with our structure (Fig. 11E) suggests that the flexible loop of Nfs1 must move toward the substrate-binding site to allow formation of the persulfurated cysteine, as proposed previously (15, 17). However, in our structure a smaller movement of the Nfs1 flexible loop would appear to be required for sulfur donation to Cys-139 of Isu1, as compared with the A. fulgidus [IscS]2·[IscU]2 complex (or the E. coli [IscS]·[IscU] complex) (14, 15) and the yeast [Nfs1]2·[Isd11]2·[Isu1]2·[Yfh1]2 complex (17).

Our model sheds new light on the molecular details of iron donation from Yfh1 to Isu1, which are still largely undefined. In the context of the [Nfs1]2·[Isd11]2·[Isu1]2·[Yfh1]2 complex, one monomer of Yfh1 is thought to bind in a pocket between Nfs1 and Isu1 through its iron-binding surface (10, 18), which includes some (Asp-86, Glu-89, Asp-101, and Glu-103) of the iron-binding residues involved in iron coordination by Yfh1 in our structure. However, in the [Nfs1]2·[Isd11]2·[Isu1]2·[Yfh1]2 complex, Yfh1 binding can only occur with the flexible loop of Nfs1 in the closed conformation, which implies that Fe-S cluster assembly begins with iron donation and that sulfur donation requires the displacement of Yfh1 from the complex (17). In our structure, however, the placement of Isu1 relative to Yfh1 and Nfs1 allows for Yfh1 and Nfs1 to simultaneously bind to Isu1 independent of the conformation of the Nfs1 loop, which is consistent with our previous observation that Isu1 and [Nfs1]·[Isd11] can simultaneously bind to oligomeric Yfh1 in solution (8). Thus, our structure provides a mechanism for concerted transfer of iron and sulfur that does not require Yfh1 to be expelled and would only require a small movement of the flexible loop of Nfs1. It is possible that the close proximity of amino acids known to be involved in sulfur donation by Nfs1 and iron donation by Yfh1 to the Fe-S cluster-coordinating residues of Isu1 allows simultaneous transfer of sulfur and iron to Isu1. We have shown that the Fe-S cluster assembly reaction is much faster when the source of elemental sulfur is Na2S (Fig. 1D) as compared with l-cysteine (Fig. 1E) (8). The lag observed in the latter reaction reflects the time needed by Nfs1 to generate elemental sulfur from l-cysteine. Based on these biochemical data, we previously suggested that oligomeric Yfh1 can adjust the rate of iron delivery to that of sulfur delivery (8). We further suggest that biochemical and structural data together support the possibility that iron and sulfur may be delivered to Isu1 simultaneously.