Abstract

Background:

Admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) is not only stressful to the patients but the patients' family members. Families are believed not to receive their required attention because their needs are incorrectly and inaccurately evaluated by the health care team. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the perceptions of ICU nurses and families regarding the psychosocial needs of families of intensive care patients.

Materials and Methods:

This descriptive-analytical study was conducted on a randomly selected population of 80 nurses and 80 family members of ICU patients. Data were collected using a two-part questionnaire containing sociodemographic characteristics and the Critical Care Family Need Inventory (CCFNI).

Results:

The rank order of the five most important CCFNI item needs identified by families were as follows: “To feel that the hospital personnel care about the patient”, “to be assured that the best care possible is being given to the patient”, “to have questions answered honestly”, “to know specific facts concerning patient's progress”, and “to be called at home about changes in the patient's condition.” The top five CCFNI item needs identified by nurses were in the following order: “To be assured that the best care possible is being given to the patient”, “to be told about transfer plans while they are being made”, “to feel that the hospital personnel care about the patient”, “to have questions answered honestly”, and “to know specific facts concerning patient's progress.”

Conclusion:

The present study showed there are similarities and dissimilarities between nurses and family members in their perceived importance of some family needs in the ICU. It can thus be inferred from our results that the participating nurses misestimated the needs of family members, attested by their wrong estimation of the most need statements.

Keywords: Family, intensive care unit, nurse, psychosocial needs

INTRODUCTION

Admission to an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) is not only stressful to the patients but the patients' family members.1,2 In fact, admission to an ICU is “viewed as a crisis for both patients and their families” (p. 491)3, because they are not adequately mentally prepared for such a stressful situation.4 Having a loved one in an ICU can impair family integrity, making some changes in family roles and responsibilities.5 Fear of death or permanent disability, uncertainty about the patient's condition and prognosis, emotional conflicts, financial concerns, role changes, and unfamiliarity of the intensive care environment, especially during the first 72 h after ICU admission, can trigger feelings of shock, anger, guilt, denial, despair, and depression within the family.2,6,7,8 The family may also experience feelings of anxiety and insecurity that are only “increased by stressful circumstances inherent to intensive care units (ICUs)” (p. 22).9 These stressful circumstances are comprised of the medical and technological equipment, the constant monitoring of the patient, and the medical device alarms.2,9 This situation may even affect, commonly delay, patient recovery and pose mental, emotional, and physical distress to the family members.10 Family members may also have difficulty coping with their stress and emotions and may use maladaptive coping strategies.11

Since most ICU patients cannot make decisions on their own medical treatment, the family may be requested to make difficult treatment decisions on the patient's behalf.12 This again multiplies the pressure on the family and heightens their emotional needs.13 Under such circumstances, the family may not be able to recognize their own needs.14 Therefore, the family's health and well-being may be affected by whether all their needs are fulfilled and by the actions of the patient's health care team.13 Meanwhile, nurses, who are in constant close contact with patients, are in an ideal position to help family members meet their needs and deal with the stressful situation.15,16 However, nurses are trained to primarily focus on the nursing needs of patients, and the needs of family members are often neglected.17,18 Sometimes, even nurses and doctors may fail to recognize the needs of patients' family members.19,20 Abazari and Abbaszadeh compared nurses and family members' perceptions of the psychosocial needs of families of critically ill patients. They concluded that both families and nurses prioritized the needs differently, but the two participating groups underlined the significance of family needs and these needs were perceived as more important by families.21 Bijttebier et al. reported that most health care professionals are not adequately aware of the particular needs of patients' families. Many health care professionals do not realize that meeting the needs of family members can improve patients' outcomes.2 While health care professionals are required to support families during the crisis of a loved one's hospitalization,2 meeting the immediate needs of families can reduce the stress of both families and the health care team.8,15

To the best of our knowledge, little research has been conducted so far on the needs of families of critically ill patients in Iran. Hence, the present study aimed to examine the perceptions of ICU nurses and families regarding the psychosocial needs of families of intensive care patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted in five metropolitan hospitals equipped with nine ICUs having 77 total ICU beds (a minimum of 4 and a maximum of 12 ICU beds in participating hospitals). The nine ICUs had a total of 174 nurses. There was one nurse per two patients in these ICUs irrespective of a charge nurse per shift in each ICU. The nine ICUs consisted of five general ICUs, one trauma ICU, one burn ICU, and two cardiac surgical ICUs. The model of critical care delivery in the Iranian ICUs is to provide total care to one or two ICU patients by one nurse.

ICU admitted patients' relatives with blood or marriage ties who were willing to participate and signed an informed consent form were recruited in this study. Individuals under 18 years of age and those with sensory deficits (blindness and deafness) or a diagnosis of mental illnesses were excluded from the study.22,23,24 The inclusion criteria for ICU nurses were a minimum education level of bachelor's degree and a minimum of 6 months of work experience in ICUs.25,26

According to the sampling formula, the number of participants was calculated to be 160 (80 nurses and 80 family members). The families of ICU admitted patients were randomly sampled during the visiting hours in ICUs. In the first instance, the number of required samples in each ICU was determined based on the number of ICU beds. The family members were then randomly selected using the Excel RANDBETWEEN function. The ICU patients were identified according to their bed numbers, and the bed numbers were used in the Excel RANDBETWEEN to recruit only one family member for each patient. Nurses were sampled in the same way according to the patients' bed numbers in morning, afternoon, and night shifts. Each participant could only participate once.

Questionnaire

A questionnaire was used to collect data from nurses and family members. The questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first part of family members' questionnaire contained questions on sociodemographic characteristics of respondents including age, gender, level of education, marital status, place of residence, job status, and family member's relationship with the patient. The first part of nurses' questionnaire comprised questions on sociodemographic characteristics of respondents including age, gender, place of residence, level of education, marital status, years of practice, and monthly working hours. The second part of the questionnaire included the Critical Care Family Needs Inventory (CCFNI). The CCFNI is a self-report questionnaire comprising 45 need-based questions on a Likert scale from 1 (not important) to 4 (very important). The CCFNI is a widely used questionnaire3,27,28,29,30,31,32 to identify the psychosocial needs of families of ICU patients in five categories: Support, comfort, information, proximity, and assurance. The forward-backward translation method was used to translate the CCFNI from English to Persian by two experts fluent in both languages. The two Persian translations were compared in order to merge the two forward translations into a single forward translation. The Persian-translated version was subsequently translated into English by two other language experts. The two English translations were then compared to reach a single backward translation. The back-translated version was compared to the original to ensure that the conceptual meaning of the questions was transferred in the Persian-translated version of the instrument. To ensure language clarity and correct order of items in the questionnaire, the Persian version was evaluated by three experts in Persian literature. No changes were made to the content of the original instrument during the translation process.

The face and content validity of the Persian version of the questionnaire were established by consultation with a panel of experts comprised of seven academic staff at the Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. The panel recommended replacing pastor with clergyman, presenting the cultural adaptation of the questionnaire. This was the only change made in the final version of the instrument. To ensure the questionnaire's reliability, internal consistency was measured (using Cronbach's alpha) and was calculated at 0.911 for family members and 0.913 for nurses subsequent to the completion of the questionnaire by 20 nurses and 20 family members.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Research and Ethical Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. All participants gave informed consent for the study.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Windows 21 (SPSS; Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all quantitative variables as mean, standard deviation, and minimum-maximum. The one-sample t-test was used to assess the psychosocial needs of the families. The Friedman test was also used for rank ordering of the psychosocial needs of the families. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

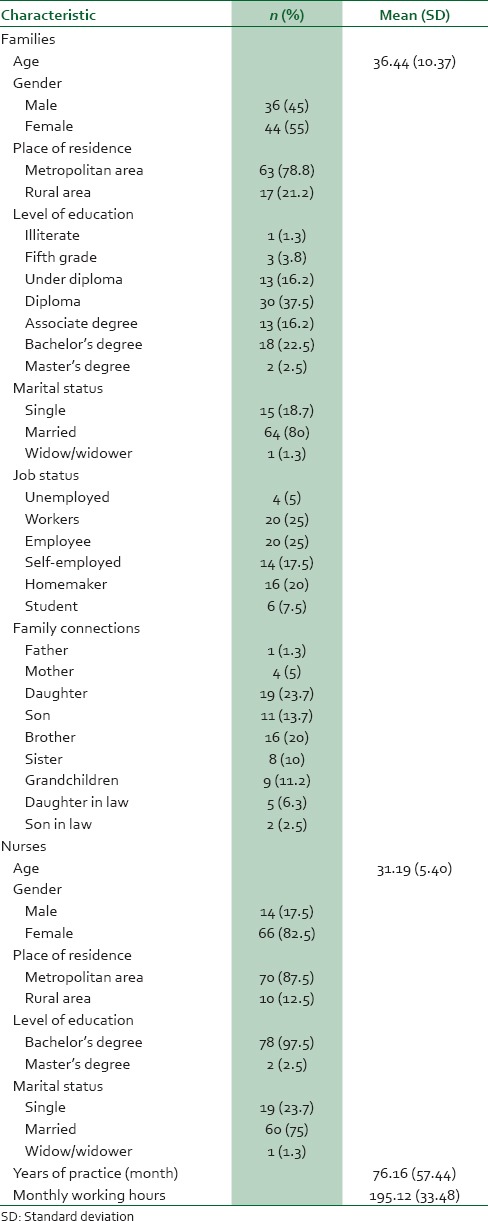

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the family members was 36.44 ± 10.30 years (range 20−65 years), and 44 (55%) were female. In addition, the mean age of the participating nurses was 31.19 ± 5.40 years (range 23−45 years), and the majority (82.5%, n = 66) were female.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of family members and nurses

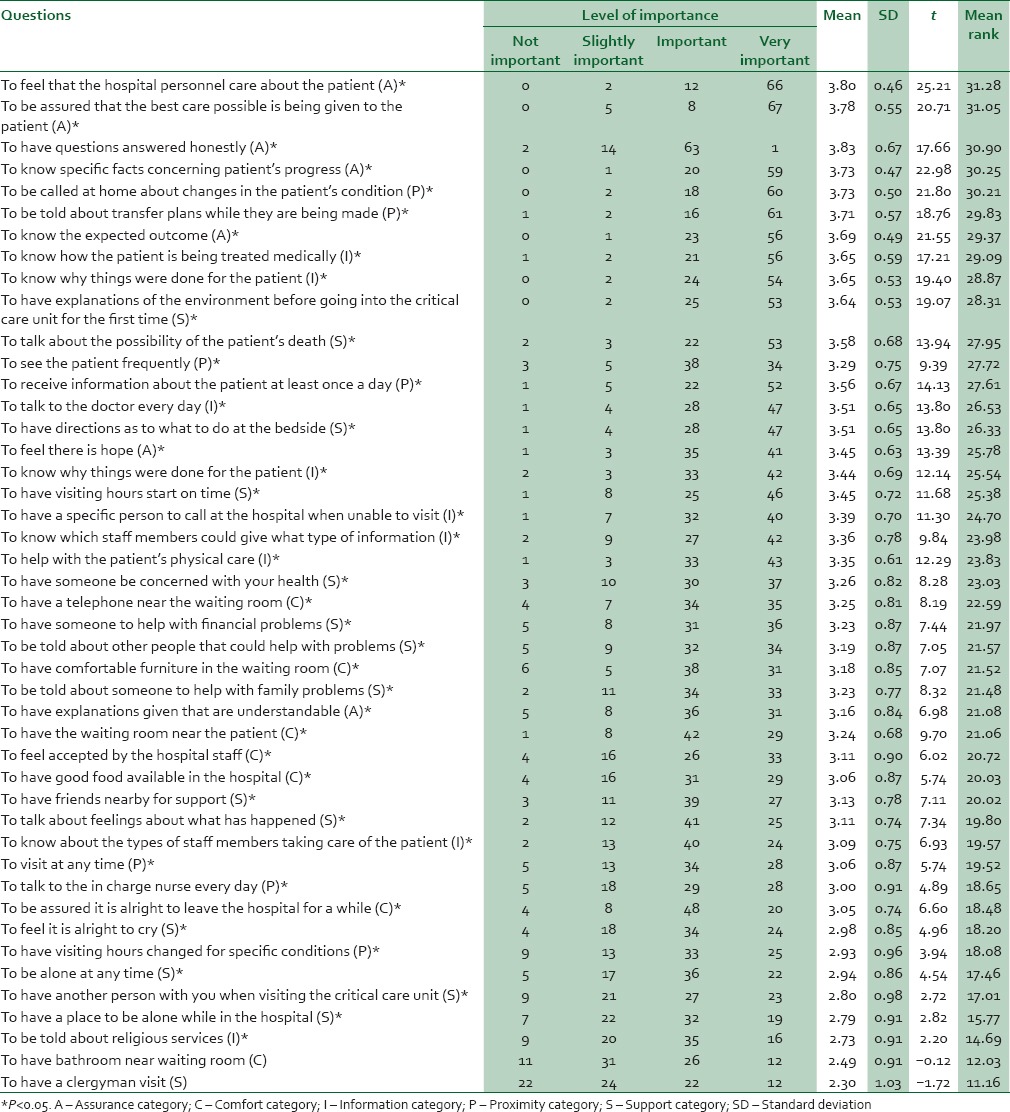

The participating family members ranked their top two needs as “to feel that the hospital personnel care about the patient” (P < 0.001) and “to be assured that the best care possible is being given to the patient” (P < 0.001). The third most important need perceived by family members was “to know specific facts concerning patient's progress” (P < 0.001), followed by (in order of importance) “to be called at home about changes in the patient's condition” (P < 0.001), “to know why things were done for the patient” (P < 0.001), “to know the expected outcome” (P < 0.001), “to have explanations of the environment before going into the critical care unit for the first time” (P < 0.001), and “to be told about transfer plans while they are being made” (P < 0.001). Family participants did not identify “to have a clergyman visit” and “to have bathroom near waiting room” as their psychosocial needs. Table 2 depicts the mean rank ordering of CCFNI items for family members.

Table 2.

Mean rank ordering of critical care family needs inventory (CCFNI) items for 80 family members

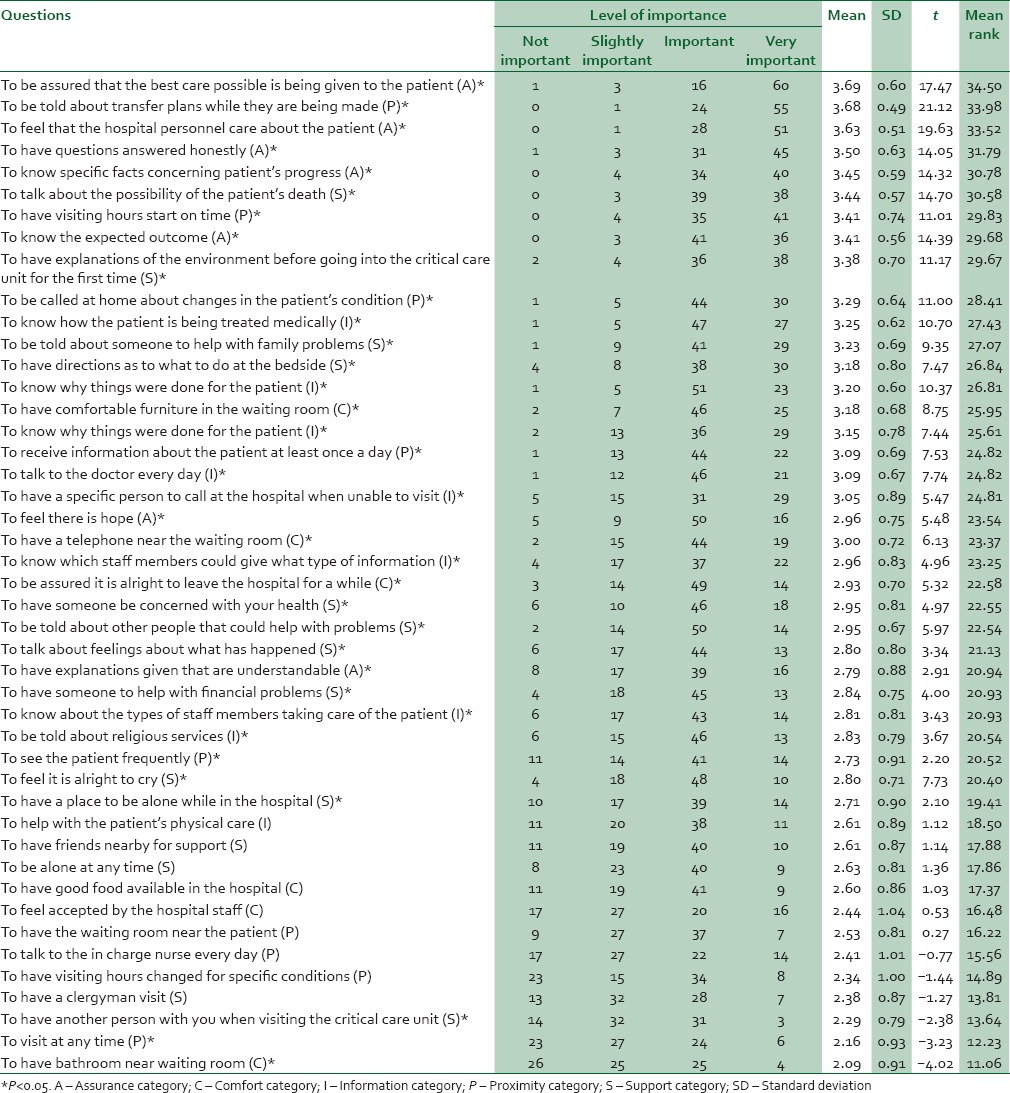

Nurses ranked the needs “to be assured that the best care possible is being given to the patient” (P < 0.001) and “to be told about transfer plans while they are being made” (P < 0.001) as the family members' top two needs (P < 0.001). Other most important needs perceived by nurses, in order of importance, were “to have questions answered honestly” (P < 0.001), “to feel that the hospital personnel care about the patient” (P < 0.001), “to have visiting hours start on time” (P < 0.001), “to know specific facts concerning patient's progress” (P < 0.001), and “to have explanations of the environment before going into the critical care unit for the first time” (P < 0.001).

However, nurses did not give high rankings to the needs “to talk to the in charge nurse every day,” “to have a clergyman visit”, “to have the waiting room near the patient”, “to have friends nearby for support”, “to be alone at any time”, and “to have a place to be alone while in the hospital.” Similarly, the needs “to feel accepted by the hospital staff”, “to have good food available in the hospital”, “to help with the patient's physical care”, and “to have visiting hours changed for specific conditions” were not given high rankings by nurses. Table 3 illustrates the mean rank ordering of CCFNI items for nurses.

Table 3.

Mean rank ordering of critical care family needs inventory (CCFNI) items for 80 nurses

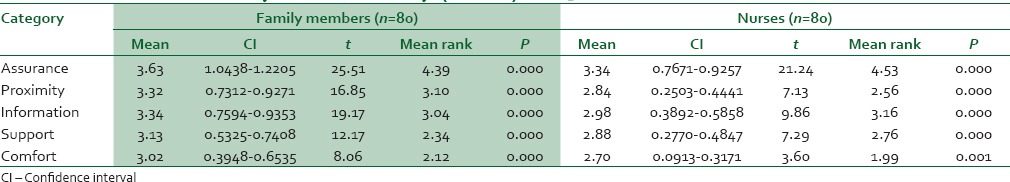

For families the following mean rank ordering emerged: Assurance, proximity, information, support, and comfort. For nurses different rankings emerged, except for assurance and comfort with the same rankings as family members. CCFNI categories and item scores are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Critical care family needs inventory (CCFNI) categories and item scores

DISCUSSION

The changing needs of patients and their families are a reflection of our changing technology and research is an ideal vehicle to explore these needs. To this end, we examined the perceptions of ICU nurses and families regarding the psychosocial needs of families of intensive care patients.

The present study showed that families ranked the need “to feel that the hospital personnel care about the patient” as their first need. This finding is in line with that of Abazari and Abbaszadeh, who used the CCFNI to compare the perceptions of 41 nurses and 41 family members about the psychosocial needs of families of patients admitted to ICU and coronary care unit.21 Due to restrictive ICU visitation policies,33 the family should be assured by the medical team that their patient is receiving the best possible care, which can enhance the family's trust in the medical team and partly reduce some of their concerns. However, the participating nurses did not rank the need “to feel that the hospital personnel care about the patient” with as high importance as family members.

In the present study, nurses ranked the need “to be assured that the best care possible is being given to the patients” as the highest priority need, whereas family members perceived this need statement as their second most important need. It seems reasonable to ascribe this difference in perceived importance of this family need to the fact that the medical team tends to focus on the patient's treatment and care on account of the critical condition of ICU patients and their need for advanced medical procedures and constant observation and nursing care.2 Furthermore, Lee and Lau examined the immediate needs of family members of ICU admitted patients in Hong Kong and found the assurance needs as family members' most important needs.3 Obringer et al. studied 50 family members of ICU patients to identify their needs in the Midwest, the United States. The study revealed the assurance needs as the most important needs of family members.34

The need “to have questions answered honestly” was ranked in the third place by family members. Hashim and Hussin in Malaysia and Hinkle and Fitzpatrick in the United States found comparable results.24,35 However, our nurse participants ranked this need statement lower in importance than family members. Bijttebier et al. examined and compared the perceptions of doctors, nurses, and relatives about the needs of relatives of critical care patients. While family members perceived the need “to have questions answered honestly” as their highest priority need, doctors and nurses ranked the need “to have explanations given that are understandable” as the most important perceived need.2 ICU patients are generally unable to express their own medical status because of altered level of consciousness and/or inability to communicate. Therefore, family members' understanding of the condition severity is based on information provided by doctors and nurses. Following admission to an ICU, inadequate information about the patient's medical condition and prognosis, length of hospital stay, and the intensive care environment will cause a feeling of shock in the family.36 However, half of the family members of critically ill patients experience inadequate communication with doctors about the patient's medical diagnosis, treatment, and chance of recovery. The resulting confusion and despair36 can even be worsened by restrictive family visitation. Providing family members with a clear explanation about their patient's medical condition, treatment care plan, and potential treatment outcomes can possibly increase their hope and strengthen their trust in the medical team.24 The families may need to have all of their questions about the patient answered honestly and adequately, particularly in the early stages of hospitalization, which may, even temporarily, reduce their stress and anxiety.

Families also ranked the need “to know specific facts concerning patient's progress” higher in importance than the nurses did for this need statement. According to Auerbach et al., “the most pressing need of family members of patients in the intensive care unit is to receive clear, understandable, and honest information about the patient's condition.”37 This finding underlines the family's need for information about the patient's progress at regular times.

Nurses ranked the need “to be told about transfer plans while they are being made” higher in importance than the family members. Moreover, nurses did not rank “to be called at home about changes in the patient's condition” with as high importance as the families. Interestingly, the need “to have a clergyman visit” was the least important need perceived by family members. This finding is in agreement with that reported by Bijttebier et al.2 This finding can be partially explained by the fact that the family members of a critically ill patient frequently neglect their own physical and emotional needs.2

Furthermore, the information and assurance needs were ranked above the needs for support, comfort, and proximity by our participating nurses. This finding is congruent with those of other investigators.12,17,19,38,39 In line with our finding, Reynolds and Prakinkit found in their study that families of ICU patients ranked the assurance and proximity needs above the needs for information, support, and comfort.40 Maxwell et al. investigated and compared nurses and families' perceptions on the needs of family members of critically ill patients. A sample of 20 family members and 30 ICU nurses completed the self-administered CCFNI. The needs for assurance and information were ranked highest by both nurses and family participants.12 The need for assurance is one of the family's primary needs in coping with a loved one's ICU hospitalization.6 They should receive the assurance they feel is needed. If the family members' needs for assurance, information, comfort, support, and proximity are addressed by the health care team, family and patient's anxiety and stress are to be reduced. Meeting the needs of patient's families can also develop their trust in the health care team, increase their satisfaction with hospital care and help them cope with the stressful situation. Not only patients but also family members should be the center of attention in the current critical care environment. Patient- and family-centered holistic critical care is intended to meet the needs of the patient as well as the patient's family. It was also surprising that our study revealed that nurses underestimated the proximity needs of the family. Families are believed not to receive their required attention because their needs are incorrectly and inaccurately evaluated by the health care team.41 Due to stringent visiting hours, the proximity needs are often left unmet. Restrictive ICU visitation policies are currently imposed in most hospitals in Iran as it is believed that the presence of family members may increase the risk of infection for patients and disrupt patients' comfort and nursing care.42 However, some clinical studies have substantiated the need for changing current ICU visitation policies,42,43,44 since the current restrictions on visiting hours are a notable source of stress not only for families but also for patients.45 According to Cullen et al., the visitation need of family members provides them with support, information, proximity, comfort, and assurance and increases their satisfaction with ICU experience.45 Moreover, Azimi Lolaty et al. examined the effects of family-friend visits on anxiety, physiological indices, and well-being of MI patients and concluded that family-friend visits can improve patients' sense of well-being, diminish their anxiety, and maintain their physiological indices within normal limits.43 Therefore, the need for families to be near their loved ones should be facilitated by changing the ICU visitation rules. The family-focused care includes providing the families with reasonable opportunities to visit their ICU admitted patients.

Families also ranked the information needs lower in importance than the nurses did. Reynolds and Prakinkit found in their study that nurses and families gave the same rank position to the information needs.40 Davidson indicates that the information needs are the primary need of family members of a critically ill patient, which are commonly left unmet.46 It should be noted that nurses have a pivotal role to play in ensuring that family needs in the ICU are to be accurately identified. They are also in a position to ensure that the unmet needs of family members of ICU patients are to be properly addressed. The support needs refer to the family's need for resources and support structures to help them cope with emotional distress and preserve their strength during their loved one's critical illness.12,14,47 Similar to the results found in previous studies,19,38 our nurse participants ranked the support needs higher in importance than the families. The families provided with emotional support can cope better with psychological stress. Other strategies to help the families adapt to their loved one's critical illness are to refer them to support groups, provide them with honest and reliable information about the patient's health condition and educational pamphlets, involve them in educational programs, and develop effective communications between families and ICU personnel. The comfort needs, on the other hand, indicates the family's need for personal comfort and includes having access to adequate and comfortable waiting rooms, telephones, bathrooms, and good food. In this study, the comfort needs were the least important needs perceived by nurses and family members, which is in line with the findings of previous studies.38,40 According to Lam and Beaulieu, “replications of Molter's study in other critical care settings have consistently shown that the information, assurance and proximity needs were ranked above support and comfort needs” for the families of ICU admitted patients.48 The patient is the center of attention by family members who are faced with a high level of emotional distress. As a result, family members may pay little attention to their personal comfort needs.2 Although the needs for comfort were not the primary consideration for our family and nurse participants, this does not indicate that the needs for comfort are not a priority need for the family members of critically ill patients. It is incumbent on the health care team to accommodate family members with the five basic needs of support, comfort, proximity, information, and assurance.

It is important to acknowledge the potential limitations of the study. A study limitation might be in the questionnaire's failure to list, although reasonably impracticable to do so, all psychosocial needs of the families of patients in the ICU. In other words, the CCFNI may have a limited capacity to reflect needs not recorded by the inventory. Another potential limitation relates to the fact that families are possibly unable to accurately express their needs during the first few days of hospitalization on account of the experience of high level of stress and a sense of crisis. Despite these limitations to the current study, it should be noted that this study included participants from multiple ICUs within five large metropolitan hospitals. In addition, this study provides insights in a topic which has not yet been adequately researched in Iran.

CONCLUSION

The present study showed there are similarities and dissimilarities between nurses and families in their perceived importance of some family needs in the ICU. The needs for assurance were ranked first by the family members and ICU nurses. Another significant finding was the difference between nurses and families in their perceived importance of the needs for proximity. ICU nurses perceived this need a low-order priority than the families. According to our results, both ICU nurses and families placed the least emphasis on the needs for comfort. Nurses also assigned a higher priority to the needs for support than families. It can also be inferred from our results that the participating nurses misestimated the needs of families, attested by their wrong estimation of the most need statements.

It is acknowledged that interpretive research studies are warranted to explore the psychosocial needs of ICU patients' families. Further research is also needed to examine the effects of emotional reactions of family members to their loved one's admission to the ICU and its impacts on their perceived psychosocial needs. Moreover, future studies can investigate the effects of other variables such as length of hospitalization in ICU and type of the illness on psychosocial needs of the patients' families.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study has been financially supported by the Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This paper is the result of a master's thesis by Hossein Roohi Moghaddam.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rodríguez AM, Gregorio MA, Rodríguez AG. Psychological repercussions in family members of hospitalised critical condition patients. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58:447–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bijttebier P, Vanoost S, Delva D, Ferdinande P, Frans E. Needs of relatives of critical care patients: Perceptions of relatives, physicians and nurses. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:160–5. doi: 10.1007/s001340000750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee LY, Lau YL. Immediate needs of adult family members of adult intensive care patients in Hong Kong. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:490–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loiselle CG, Gélinas C, Cassoff J, Boileau J, McVey L. A pre-post evaluation of the Adler/Sheiner Programme (ASP): A nursing informational programme to support families and nurses in an intensive care unit (ICU) Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2012;28:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maruiti MR, Galdeano LE, Farah OG. Anxiety and depressions in relatives of patients admitted in intensive care units. Acta Paul Enferm. 2008;21:636–42. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:987–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Masri MM, Fox-Wasylyshyn SM. Nurses' roles with families: Perceptions of ICU nurses. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2007;23:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheafer H. The met and unmet needs of families of patients in the ICU and implications for social work [PhD thesis] Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania; 2010. p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delva D, Vanoost S, Bijttebier P, Lauwers P, Wilmer A. Needs and feelings of anxiety of relatives of patients hospitalized in intensive care units: Implications for social work. Soc Work Health Care. 2002;35:21–40. doi: 10.1300/J010v35n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadeghi Z, Payami Bosari M, Mousavi Nasab N. The effect of family cooperation on the care of the patient hospitalised in critical care unit on family anxiety. Nurs Midwifery Care J. 2012;2:10–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casarini KA, Gorayeb R, Basile Filho A. Coping by relatives of critical care patients. Heart Lung. 2009;38:217–27. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maxwell KE, Stuenkel D, Saylor C. Needs of family members of critically ill patients: A comparison of nurse and family perceptions. Heart Lung. 2007;36:367–76. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyrie LS, Mosenthal AC. Care of the family in the surgical intensive care unit. Anesthesiol Clin. 2012;30:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naderi M, Rajati F, Yusefi H, Tajmiri M, Mohebi S. Health literacy among adults of Isfahan, Iran. J Health Syst Res. 2013;9:473–83. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckley P, Andrews T. Intensive care nurses' knowledge of critical care family needs. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2011;27:263–72. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox-Wasylyshyn SM, El-Masri MM, Williamson KM. Family perceptions of nurses' roles toward family members of critically ill patients: A descriptive study. Heart Lung. 2005;34:335–44. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chien WT, Chiu YL, Lam LW, Ip WY. Effects of a needs-based education programme for family carers with a relative in an intensive care unit: A quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acaroglu R, Kaya H, Sendir M, Tosun K, Turan Y. Levels of anxiety and ways of coping of family members of patients hospitalized in the neurosurgery intensive care unit. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2008;13:41–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Omari FH. Perceived and unmet needs of adult Jordanian family members of patients in ICUs. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2009;41:28–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Söderström IM, Benzein E, Saveman BI. Nurses' experiences of interactions with family members in intensive care units. Scand J Caring Sci. 2003;17:185–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2003.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abazari F, Abbaszadeh A. Comparison of the attitudes of nurses and relatives of ICU and CCU patients towards the psychosocial needs of patients relatives. J Qazvin Univ Med Sci. 2001;19:58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailey JJ, Sabbagh M, Loiselle CG, Boileau J, McVey L. Supporting families in the ICU: A descriptive correlational study of informational support, anxiety, and satisfaction with care. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2010;26:114–22. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAdam JL, Fontaine DK, White DB, Dracup KA, Puntillo KA. Psychological symptoms of family members of high-risk intensive care unit patients. Am J Crit Care. 2012;21:386–93. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2012582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashim F, Hussin R. Family needs of patient admitted to intensive care unit in a public hospital. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci. 2012;36:103–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brysiewicz P, Bhengu BR. The experiences of nurses in providing psychosocial support to families of critically ill trauma patients in intensive care units. South Afr J Crit Care. 2010;26:42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gondwe WT, Bhengu BR, Bultemeier K. Challenges encountered by intensive care nurses in meeting patients' families' needs in Malawi. Afr J Nurs Midwifery. 2011;13:92–102. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takman C, Severinsson E. The needs of significant others within intensive care - the perspectives of Swedish nurses and physicians. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2004;20:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Lemaire F, Mokhtari M, Le Gall JR, et al. Meeting the needs of intensive care unit patient families: A multicenter study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:135–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2005117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tin MK, French P, Leung KK. The needs of the family of critically ill neurosurgical patients: A comparison of nurses' and family members' perceptions. J Neurosci Nurs. 1999;31:348–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dockter B, Black DR, Hovell MF, Engleberg D, Amick T, Neimier D, et al. Families and intensive care nurses: Comparison of perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 1988;12:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(88)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molter NC. Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: A descriptive study. Heart Lung. 1979;8:332–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinkert C, Holtgräwe M, Remmers H. Needs of relatives of breast cancer patients: The perspectives of families and nurses. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spreen AE, Schuurmans MJ. Visiting policies in the adult intensive care units: A complete survey of Dutch ICUs. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2011;27:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obringer K, Hilgenberg C, Booker K. Needs of adult family members of intensive care unit patients. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:1651–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinkle JL, Fitzpatrick E. Needs of American relatives of intensive care patients: Perceptions of relatives, physicians and nurses. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2011;27:218–25. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Askari H, Forozi M, Navidian A, Haghdost A. Psychological reactions of family members of patients in critical care units in Zahedan. J Res Health. 2013;3:317–24. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Auerbach SM, Kiesler DJ, Wartella J, Rausch S, Ward KR, Ivatury R. Optimism, satisfaction with needs met, interpersonal perceptions of the healthcare team, and emotional distress in patients' family members during critical care hospitalization. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14:202–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gundo R. Comparison of Nurses' and Families' Perception of Family Needs in Intensive Care Unit at a Tertiary Public Sector Hospital [Master's thesis] Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand; 2010. p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freitas KS, Kimura M, Ferreira KA. Family members' needs at intensive care units: Comparative analysis between a public and a private hospital. Rev Lat-Am Enfermagem. 2007;15:84–92. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692007000100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reynold J, Prakinkit S. Needs of family members of critically ill patients in cardiac care unit: A comparison of nurses and family perceptions in Thailand. Journal of Health Education. 2008;31:53–66. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verhaeghe ST, van Zuuren FJ, Defloor T, Duijnstee MS, Grypdonck MH. How does information influence hope in family members of traumatic coma patients in intensive care unit? J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1488–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghiyasvandian S, Abbaszadeh A, Ghojazadeh M, Sheikhalipour Z. The effect of open visiting on intensive care nurse's beliefs. Res J Biol Sci. 2009;4:64–70. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Azimi Lolaty H, Bagheri-Nesami M, Shorofi SA, Golzarodi T, Charati JY. The effects of family-friend visits on anxiety, physiological indices and well-being of MI patients admitted to a coronary care unit. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2014;20:147–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fumis RR, Ranzani OT, Faria PP, Schettino G. Anxiety, depression, and satisfaction in close relatives of patients in an open visiting policy intensive care unit in Brazil. J Crit Care. 2015;30:440.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cullen L, Titler M, Drahozal R. Family and pet visitation in the critical care unit. Crit Care Nurse. 2003;23:62–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davidson JE. Family-centered care: Meeting the needs of patients' families and helping families adapt to critical illness. Crit Care Nurse. 2009;29:28–34. doi: 10.4037/ccn2009611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leske JS. Interventions to decrease family anxiety. Crit Care Nurse. 2002;22:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lam P, Beaulieu M. Experiences of families in the neurological ICU: A“bedside phenomenon”. J Neurosci Nurs. 2004;36:142–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]