Abstract

The appointment of a healthcare proxy is the most common way through which patients appoint a surrogate decision maker in anticipation of a future time in which they may lack the ability to make medical decisions themselves. In some situations, when a patient has not previously appointed a surrogate decision maker through an advance directive, the healthcare team may ask whether the patient, although lacking the capacity to make a healthcare decision, might still have the capacity to appoint a healthcare proxy. In this article the authors summarize the existing, albeit limited, legal and empirical basis for this capacity and propose a model for assessing capacity to appoint a healthcare proxy that incorporates clinical factors in the context of the risks and benefits specific to surrogate appointment under the law. In particular, it is important to weigh patients’ understanding and choice within the context of the risks and benefits of the medical and interpersonal factors. Questions to guide capacity assessment are provided for clinical use and refinement through future research.

Keywords: Advance directives, capacity, competency, healthcare power of attorney, healthcare proxy, informed consent

CASE EXAMPLE

Clinical Factors

Ms. A is an 80-year-old woman admitted to the hospital for a hip fracture after a fall that was ultimately determined to be mechanical in nature. Upon presentation to the hospital, Ms. A, who lives with her daughter, appeared disheveled, had lost 20 pounds over the past 4–6 months, and had not been taking her medications as evidenced by pharmacy records. She was acutely confused and diagnosed with a urinary tract infection. Ms. A exhibited disorientation, poor attention, and periods of agitation and paranoid ideation. She was determined to lack capacity to consent to hip surgery and had no valid advance directive. By hospital Day 2, the patient demonstrated a consistent preference that the medical team consult with her daughter for all medical decisions. The team debated whether Ms. A had the requisite mental capacity to execute an advance directive to formally designate her daughter as her surrogate decision maker.

Risk-to-Benefit Considerations

During the team discussion, an adult protective services social worker called the unit to report an open protective services case regarding Ms. A, related to concerns about the care provided by her daughter. However, the orthopedics service anticipated that without surgery Ms. A would not be able to walk again and that a delay could cause the surgery to be more complex, increase postoperative pain, prolong the postoperative course of rehabilitation, and could result in a permanent limp.

Legal Factors

The orthopedics service, deciding that the surgery was urgent but not emergent, declined to proceed with the operation without informed consent. Ms. A was hospitalized in a state without a default surrogate consent statute, meaning that in certain medical situations where there is not a legal surrogate, next of kin lack legal authority to make a decision. Under the specific circumstances (i.e., pending protective services involvement and the relevant case and statutory law in the jurisdiction), the hospital’s legal counsel advised that Ms. A’s daughter could not provide consent for nonemergent surgery without a valid advance directive or formal legal authority (e.g., guardianship).

Issues

How should the team approach evaluation of Ms. A’s capacity to execute a healthcare proxy? What level of capacity must Ms. A. demonstrate for the appointment to be legally and ethically valid? To what extent must an evaluation of Ms. A’s capacity to appoint a proxy consider the appropriateness of the proxy? What are the ethical issues in providing care, determining capacity, and/or pursuing guardianship?

INTRODUCTION

For medical treatment to occur, a patient must give informed consent. When a patient lacks the capacity to consent to medical treatment, a substitute (or surrogate) decision maker must be identified and consulted. Surrogate decision makers are formally engaged in one of three ways: by advance directives (e.g., a healthcare proxy [HCP]), by court order (e.g., guardianship), or, in some cases, through laws that establish a default hierarchy of decision makers in the absence of a prior appointment. The HCP is the most common way through which patients appoint a surrogate decision maker.1 An HCP is a document in which a patient, referred to as the “principal,” appoints an “agent” to make decisions on the patient’s behalf in the event that, at some future time, the patient no longer possesses the requisite capacity to make his or her own healthcare decisions. The HCP document may also be instructional, giving written information about a patient’s wishes or goals in the event of future incapacity. The latter type of advance directive, when written in a separate document, is often referred to as a “living will.” The HCP has been criticized because patients and proxies often do not make the same choices and because instructional directives may be difficult to interpret,1–6 although the controversy remains.7 In this article we do not discuss instructional directives.

Some confusion may arise because HCP is often informally used to refer to the healthcare agent. Additionally, there is some variable usage and understanding of the terms, depending on the practitioner and the jurisdiction. An HCP may also be referred to as a durable power of attorney for healthcare, with some variation across jurisdictions.8 However, the term “durable power of attorney” is more often used to refer to an instrument appointing an agent for financial decisions. A “durable” power enables the agent to act for the principal beginning either at a specified point in time or at some unspecified time in the future should the principal lose capacity to make healthcare decisions. What makes a durable power of attorney for healthcare “durable” is that it continues to remain in effect or, alternatively, becomes effective after the principal loses capacity to make healthcare decisions and remains effective either until it is revoked by the principal, the principal regains capacity, or the principal dies.

Typically, HCPs remain inactive, going into effect only at a future time when the patient is unable to make decisions for him- or herself. Many but not all jurisdictions require this delayed effectiveness, sometimes referred to as a “springing power.” The authority of the agent to make decisions is typically established based on a clinical judgment that the patient has lost the capacity to consent to healthcare treatment. The assessment of healthcare consent capacity considers the patient’s process of choosing what is done to his or her own body and is typically based on an assessment of the patient’s understanding, appreciation of, and reasoning about diagnostic information and treatment options, as well as the patient’s ability to express a stable choice.4,9–11 Consent capacity is diminished in dementia and other neurocognitive conditions associated with impaired cognitive functions and more variably in neuropsychiatric conditions.12–17

The best clinical practice is to ask patients to execute an HCP as part of routine outpatient care so they are prepared in case of a future incapacitating illness. The Patient Self Determination Act,18 a federal law enacted in 1990, requires that patients be asked if they have an HCP and, if not, to be provided information about the right to execute one. In cases such as Ms. A.’s, the situation described might have been averted had she previously appointed her daughter as her healthcare agent, pursuant to an HCP, at a prior point in time at which she clearly had the capacity to do so.

In many situations, as a practical matter, healthcare decisions are made by family members even in the absence of a formally appointed surrogate and may be permissible under a jurisdiction’s common law (case law). In general, the extent to which a formally appointed surrogate is required to proceed with medical care will vary based on the case and statutory law framework of the state; the legal counsel provided by the attorney for the healthcare institution; and the material, substantial, and probable risks of treatment or no treatment, considering the magnitude of the risk and likelihood of harm to the patient if the proposed medical or surgical intervention is not undertaken forthwith.19 The law allows for delivery of life-saving treatment without any consent1 or when a patient is undergoing court-ordered compulsory treatment.20–22 In nonemergent situations, some states routinely recognize family members as de facto surrogates but may impose restrictions on their decision-making authority for specific situations, such as withdrawing life-sustaining treatment.23 In the example of Ms. A., the hospital’s legal counsel interpreted state law as prohibiting surrogate consent for surgery by family or next of kin in the absence of a formal surrogate. Emergency guardianships are thus frequently sought in such situations—a less than ideal, albeit necessary, solution when patients who lack both capacity and aHCP, require urgent, but not emergent or imminently life-saving, interventions. In these situations, to avoid the potentially over-intrusive intervention of guardianship and to recognize the patient’s autonomy, the healthcare team may question whether the patient, although lacking capacity to make healthcare decisions, nonetheless possesses the capacity to execute an HCP.

In this article we review the current legal and scientific basis of capacity to execute an HCP, a legal transaction involving executing a document to appoint another to have surrogate authority. We discuss the ways in which the capacity to execute an HCP is distinct from medical decision-making consent capacity23 whose legal, empirical, and clinical basis is well articulated.9 We aim to integrate the legal and scientific literature within the contextual parameters of surrogate consent as a starting point for ongoing debate and empirical study.

LEGAL BASIS

In resolving HCP matters, courts are inclined to rely on a standard of contractual capacity, if capacity is challenged in a case or controversy (e.g., “the mental capacity required to execute a general durable power of attorney is essentially the same as and equates to the mental capacity required to enter into a contract”).24 At least one state, California, affirms that standard in its statute.25 The test of mental capacity to contract has been stated in many ways but generally follows some variation of the following: “whether the person in question possesses sufficient mind to understand, in a reasonable manner, the nature, extent, character, and effect of the particular transaction in which [he] is engaged, whether or not [he] is competent in transacting business generally.”26 Thus, “if the act or business being transacted is highly complicated, a higher level of understanding may be needed to understand its nature and effect, in contrast to a very simple contractual arrangement.”27 However, although this approach sounds sensible in principle, it could be interpreted to mean that the standard should differ for every contract depending on the contract’s complexity. Furthermore, it provides no guidance as to how such a test is to be applied to any specific circumstance, such as an HCP.

A natural starting point for understanding the particular circumstance of HCP capacity is the proposed model legislation regarding advance directives, the 1993 Uniform Health-Care Decisions Act,28 which has been adopted in a number of states, including Alabama, Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, New Mexico, Wyoming, and Kansas. This model legislation is similar to policy guidelines from a group of experts, such as the Institute of Medicine, in that the model legislation was developed by a group of legal experts. However, the Uniform Act is silent on the issue of capacity to execute an HCP. It specifically defines healthcare consent capacity but not capacity to execute an HCP nor capacity to designate a surrogate decision maker.28 Furthermore, it does not refer to consent capacity as a standard for HCP capacity.

Progressing beyond the silence of the Uniform Act, some jurisdictions, such as Massachusetts, use “of sound mind and under no constraint or undue influence (201 D §2)” as the benchmark for the ability of an individual to complete an HCP,29 the only formally recognized healthcare advance directive in Massachusetts. It is the responsibility of an adult witness to the completion of the HCP to ensure the patient is of sound mind and free will. Case law does not provide additional guidance regarding the standard for “sound mind.” The acceptability within these laws of a lay witness to determine the soundness of the patient’s mental status would support that the gross appearance of sound mind (i.e., absence of obvious cognitive limitation or psychopathology) is sufficient. The statute furthermore explicitly states that there is a presumption of capacity to execute an HCP.

Two states, Vermont and Utah, provide standards for capacity to execute an HCP. These states also distinguish the capacity to appoint an agent from the healthcare consent capacity. Utah presumes an individual’s capacity to appoint a healthcare agent30 but also defines the “capacity to appoint an agent” as meaning that the individual “understands the consequences of appointing a particular person as agent (§103 (6)).”30 Utah defines healthcare consent capacity as the “ability to make an informed decision about receiving or refusing health care (§103 (13 a–c))” and further includes the ability to understand the nature and consequences of treatment, to rationally evaluate the proposed treatment, and to communicate a decision as elements of making the informed decision.30

Perhaps the most important contribution of the Utah statute is its clear recognition that an individual who lacks healthcare decision-making capacity also lacks the ability to give a healthcare instructional directive guiding treatment and treatment preferences but may nonetheless “retain the capacity to appoint an agent (§105 (2b)).”30 Furthermore, the law gives guidance regarding the factors to consider in determining whether the individual who lacks the capacity to make a healthcare decision retains the capacity to appoint a healthcare agent.30 The specified factors are whether 1) the individual has expressed, over time, an intent to appoint the same person as agent; 2) the choice of agent is consistent with past relationships/behavior or if it is a departure; and 3) there is “reasonable justification” for the change, and whether the expression of the intent to appoint the agent occurs at times or in settings in which the individual has the greatest ability to make and communicate decisions.

The Vermont statute explicitly defines the capacity to execute an HCP as 1) a basic understanding of what it means to have another individual make healthcare decisions for oneself, 2) who would be an appropriate individual to make those decisions, and 3) identification of whom the individual wants to make healthcare decisions for the individual.31 In addition, the Vermont statute, like Utah, contains a separate and distinct definition of the capacity to make a healthcare decision. Vermont law defines healthcare consent capacity possessing a basic understanding of the diagnosed condition and the benefits, risks, and alternatives to the proposed healthcare.31

In addressing the continuum from a so-called sniff test of sound mind and voluntariness attested to by a lay witness to the more rigorous statutory definitions of Utah and Vermont, one consideration is the effect of the standard on the administration of the healthcare and legal systems. There is a balance between efficiency and effectiveness of healthcare delivery and avoiding error (appointments made by incompetent principals). In other words, the higher the standard for capacity to designate an agent, the higher the potential burden in proving that the individual’s HCP is valid, and potentially the greater the likelihood of court challenge and involvement in the delivery of medical care. One distinct advantage of the HCP is the prevention of court involvement in adjudicating private matters better decided by individuals themselves. It is no accident that the federal law requiring healthcare institutions to ask all admitted patients about advance directives, the Patient Self Determination Act of 1990,18 was passed in the same year that the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark opinion in the Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health case.32 This case considered the right of patients to autonomy and self-determination but also the ability of states to require a high burden of proof regarding a patient’s prior expressed wishes. Simply put, the very availability and reliability of an HCP is a critical means of avoiding court intervention in personal medical decisions.

On the other hand, as illustrated by the case of Ms. A, too lax a standard could lead to the appointment of an agent by a patient who is too cognitively limited to understand the risks posed by appointment of that agent but who appears conversational and grossly intact to a layperson. In other words, Ms. A. could be in the position of giving added authority to the very individual who has already raised concern regarding that individual’s ability to meet Ms. A’s care needs and act for her well-being.

EMPIRICAL STUDIES OF CAPACITY TO APPOINT A HEALTHCARE SURROGATE

The research literature provides some guidance supporting the ability of an individual to appoint a healthcare agent even in the setting of cognitive impairment. One approach to measuring the capacity to appoint a healthcare surrogate used in empirical investigation is an individual’s understanding of the instrument used to make those appointments, specifically 1) the right to make decisions about one’s own medical treatment, 2) the power to ask someone else to do so if unable, 3) that conferring that power could include a “life or death” outcome, and 4) that there is a document to sign to confer this power.33 When this capacity was measured as the ability to demonstrate such understanding (scored as recall and recognition of information), a finding of capacity or incapacity was associated with overall level of cognitive impairment on the Mini-Mental State Exam.33 However, even some patients with significant cognitive impairment on the Mini-Mental State Exam (score 10 or less) demonstrated adequate understanding of the act of appointing a healthcare agent. These findings are similar to studies of capacity to consent to treatment that found some patients with dementia may continue to demonstrate some degree of understanding of diagnostic and treatment information while showing more difficulty with appreciation of and reasoning about that information.16,34

Another approach to measuring the capacity to appoint a healthcare surrogate used in empirical studies has been to simply assess the consistency of a person’s choice of proxy. Nursing home residents named consistent choices 80% (at the beginning and end of an interview)33 to 55% (at 1-week intervals on three occasions)35 of the time (i.e., inconsistent 20%–45% of the time). Like understanding of an HCP, the ability to name a consistent choice was associated with level of cognitive impairment.33 These findings are broadly consistent with other studies finding that even when individuals lack the capacity to make treatment decisions, they may still be able to express basic healthcare values with some demonstrable degree of consistency.36

There is an evolving scientific literature on the surrogate consent for research.23 As with healthcare consent, capacity to consent to research is reduced in individuals with Alzheimer disease,37,38 mild cognitive impairment,39 and, more variably, psychiatric illness.40,41 In the event that an individual is not able to consent to research, a legally authorized representative may be able to do so. The authority of a healthcare proxy to consent to research is unclear in the absence of specific directions in a previously executed surrogate appointment.8 Patients who lack the capacity to consent to research may still be capable of appointing a research proxy.42

In sum, the scientific literature is scant, but what literature is available suggests that understanding of the right to make decisions, the power and significance of conferring decision making to another, and the HCP as the instrument to do so are related to but not entirely dependent on overall cognitive functioning as measured in these studies by Mini-Mental State Exam scores. Additionally, these studies find that consistency in identifying the same person as an HCP (over a brief period) is variable and related to cognitive functioning.

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES: CONSIDERATION OF RISKS AND BENEFITS

Like any assessment of capacity, the assessment of capacity to appoint a healthcare agent can be usefully framed in the context of values and risks,43 bringing an ethical context to the consideration of the capacity issue. Questions regarding an adult’s capacity to appoint a healthcare surrogate typically arise when healthcare decisions are urgently needed and risks may run high, including critical pharmaceutical and surgical treatments and transfers to other settings of care. The benefits of readily allowing the appointment of a healthcare surrogate in a crisis situation may be that the patient’s care proceeds in a manner the patient would want, without unnecessary delay. Importantly, the benefit should be to the patient, not the healthcare system—notwithstanding increasing economic pressure for rapid treatment and discharge. The risks of not allowing the appointment, particularly in a state without default surrogate consent statutes, is that the patient’s care may be delayed while a guardian is appointed, a process that may be time consuming and costly, may result in the same choice of a surrogate (e.g., close family member) the person would have appointed, may increase the risk of poor outcome to the patient waiting for the required treatment, and may also stress the patient and family caregivers through anxiety-provoking proceedings.

The risk of the individual’s specific medical situation is also a central consideration. One set of risks is associated with treatment choices facing the patient and the risks associated with moving forward with the care as recommended and that of not moving forward. For a patient with a narrow and time-sensitive window of opportunity for a potentially life-saving treatment, establishing too high a standard for capacity to designate a surrogate decision maker could result in the patient experiencing a poor clinical outcome.

A second set of risks is the potential for exploitation or malfeasance by a surrogate decision maker. The limited empirical study of capacity to appoint a healthcare surrogate suggests that just because a person can name a healthcare proxy once, this may not represent his or her only choice or a stable choice.35 Although individuals can and sometimes do have a valid change of mind, findings of inconsistency at the beginning and end of an interview should sound a note of caution, particularly in the setting of potential malfeasance by the surrogate decision maker. Inconsistency could also reflect influence by a family member who has recently communicated with the patient. For example, in rare situations a desire to maintain financial benefits that a patient receives could enter into a family member’s desire to be a healthcare agent in order to keep a patient alive. Some state laws recognize that the capacity to execute an HCP involves a relational element—not just the capacity of the principal but the appropriateness of the agent. The person selected by the principal must be “appropriate,”31 and the selection by the principal must be free from constraint and undue influence in the completion of the HCP. This suggests the clinician evaluating capacity is obliged to consider whether there is agreement among various family members regarding the course of care and whether any of the family members has a conflict of interest or even a history of adult protective violations. Such considerations are a reminder that an evaluation of capacity is never focused on the absolute level of functioning in the identified patient but the assessment of that functioning within the context of the situation, system of care, and demands or supports for the individual.44 As a general rule, this risk can be managed or even minimized through careful attention to and assessment of the nature and quality of the relationship between the patient and the proposed surrogate decision maker, the history of the surrogate decision-maker’s involvement in the patient’s care, and the apparent concordance or discordance between the proposed surrogate’s voiced understanding of the patient’s preference and the treating team’s understanding of the patient’s anticipated preferences.

INTEGRATING LAW, SCIENCE, AND ETHICS: CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

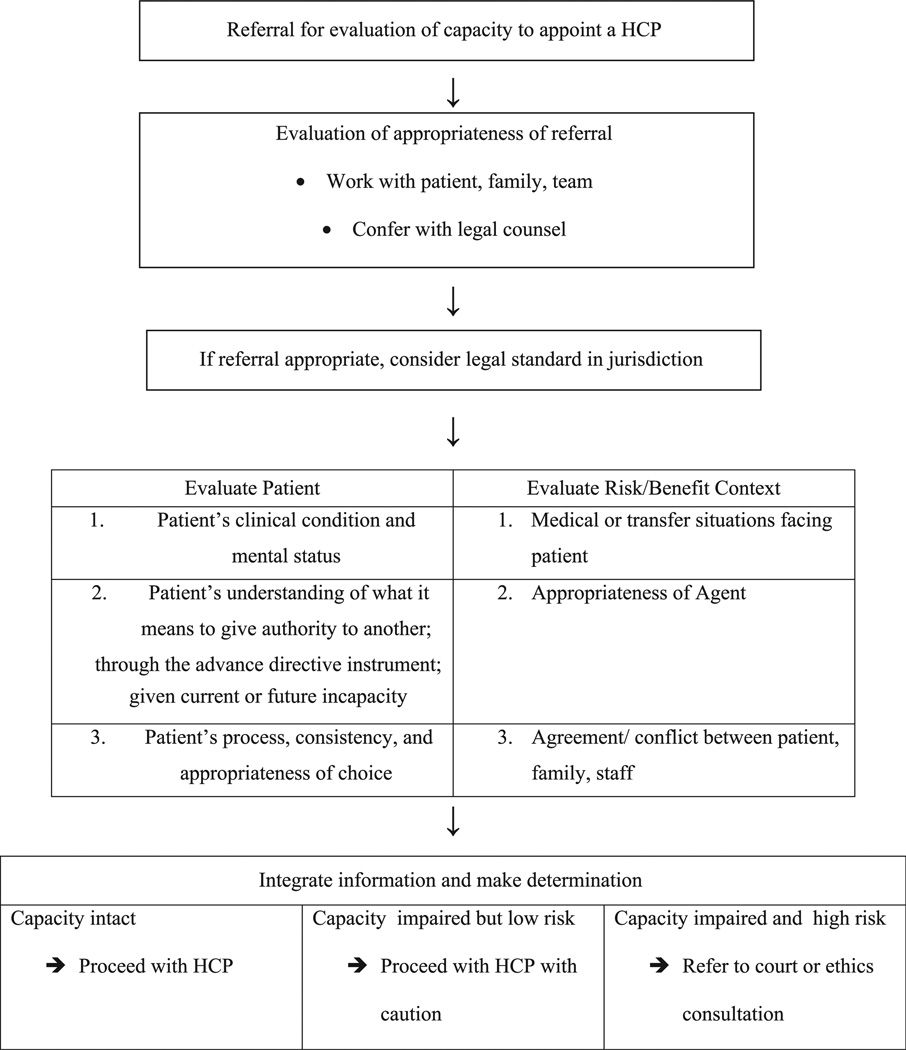

How might we integrate the legal and scientific bases for capacity to appoint a healthcare surrogate, considering the ethical and situational context of surrogate appointment? As illustrated in Table 1, we first suggest—as with any clinical capacity evaluation request—the referral must be evaluated for appropriateness.43 Frequently, the clinical issue at hand can be appropriately negotiated and more informally resolved through working with the patient, family, and healthcare team. When necessary, legal counsel can be obtained to determine if the matter requires a more formal approach.

TABLE 1.

Framework for Clinical Assessment of Capacity to Appoint a Healthcare Proxy

Assuming it does, the legal standard within the jurisdiction forms a starting point for considering the evaluation of capacity. Most statutes do not provide clear legal guidance on capacity to appoint an HCP, but those that do distinguish this capacity from medical decision-making consent capacity. The Utah and Vermont statutes, as well as the contractual capacity analog, delineate a standard of understanding on the execution of the HCP transaction. An additional requirement particularly relevant in cases like Ms. A (i.e., when the person is contemporaneously unable to consent and the power of the agent would be conferred immediately)45 might include an understanding that the individual needs assistance from someone else to make healthcare decisions. Further, the Utah and Vermont statutes and the scientific literature also support a standard related to the choice of the agent.

We suggest that these two elements—understanding and choice—can be more specifically defined in reference to the reviewed law and science as indicated in Table 1. The evaluation of capacity to execute an HCP may consist of 1) capacity to understand the meaning (a) to give authority to another to make healthcare decisions, (b) through the HCP, (c) in the event of future or considering current diminished capacity to consent to treatment and 2) capacity to (a) determine and (b) express a consistent choice (c) of an appropriate surrogate. An appropriate surrogate may be defined as someone with whom the principal has a social (not professional) relationship, who knows the person’s values, and who is willing (expresses interest and concern).46,47 This approach, we believe, provides a sufficiently high standard to avoid error and allow for completion of an HCP for the provision of care but a low enough standard to avoid burdensome challenges of proof and legitimacy. Furthermore, in situations where the identified individual to serve as healthcare agent has a history of inability to fulfill his or her responsibility, such as in the case of Ms. A, it should alert clinicians to ask additional questions and engage in a discussion with the patient about their understanding of the individual whom they have chosen. Situations in which there appears to be fluctuation in choice depending on external influences should also alert the clinician to engage in further investigation. For example, a situation in which an individual appears to change his or her choice of agent in proximity to interactions or visits with potential agents might raise concern about coercion, pressure, or lack of voluntariness.

The outcome of a capacity assessment is not merely the consideration of the patient’s abilities for understanding and expression of a choice but an integration of these functional abilities in context—the risks and benefits of the decisions facing the patient and an assessment of the appropriateness of the agent, such as is outlined in Table 1. Therefore, the assessment task does not begin and end with the patient but must include an assessment of the healthcare and social situation. Risks and benefits noted previously in this article may include the urgency and risks in the medical and/or transfer decisions facing the patient as well as available information about the appropriateness of the agent, which may usually be gleaned through dialogue with the agent, feedback from the healthcare team, and, in some situations (the ones more likely to proceed to formal consultation and evaluation), adult protective services. In our clinical experience, these factors do enter into whether teams approach a situation more informally, in collaboration with family, versus refer the matter to legal counsel and psychiatric consultation liaison. Our review of the limited legal and scientific literature confirms that it is correct to consider the appropriateness of the agent and the clinical situation at hand. The integration of the functional data with the contextual situation is a professional clinical judgment (i.e., there is no simple equation) that draws from experience and training in cognitive assessment, psychiatric consultation liaison, and ethics consultation.

Upon consideration and integration of the patient’s functional abilities and the situational risks and benefits, the clinician may decide that the patient has sufficient capacity to execute an HCP and recommend to proceed with that process, or the clinician may decide there is some impairment but the risks are low, so the team may proceed to support the patient in executing the HCP with caution. Finally, the clinician may believe the patient lacks capacity and the risks are high, recommending the team proceeds to a consult with the ethics committee (if applicable in the setting) or to guardianship.

How might a clinician evaluate the patient’s abilities for understanding and choice? In approaching such an evaluation, the clinician may wish to attend to the disclosure process as well as follow-up queries. Table 2 provides possible elements to disclose to a patient regarding execution of an HCP, which would need to be adjusted depending on the setting and jurisdiction of practice. Because it is important to evaluate understanding and not memory, the clinician may wish to provide the patient “bullet points” with which to refer, as in Table 3, to enhance comprehension, while of course making sure the patient does not just “parrot back” the points. After disclosure, potentially broken into chunks of information, the clinician may ask specific questions of the patient, as provided in Table 4.

TABLE 2.

Suggested Language to Use for Disclosure

An advance directive

|

You name or appoint the person you want to speak for you

|

To complete an advance directive

|

To change my advance directive

|

TABLE 3.

Suggested Bullet Points to Use as an Aid During Disclosure

Advance directive

|

Naming a person

|

To complete

|

To change

|

TABLE 4.

Questions for Clinical Assessment

| Q1: | What is an advance directive? |

| A: | A legal form that helps doctors and family members understand wishes about healthcare at a future time. |

| Q2: | What is a good thing about having an advance directive? |

| A: | It can help your doctors and family decide about treatments if you are too ill to decide for yourself, following your values and wishes. |

| Q3: | What does a healthcare agent or proxy do for you? |

| A: | Makes healthcare decisions [if appropriate, inquire about potentially serious outcomes of such decisions]. |

| Q4: | What persons would you consider to be your agent? |

| A: | [Specific to person: any adult the person knows and has a social relationship with, such as spouse, adult child, parent, sibling, grandparent, grandchild, or a close friend]. |

| Q5: | Who would you choose as your agent? |

| A: | [Specific to person] |

| Q6: | Why would you choose/trust this person? |

| A: | [Specific to person: identifies someone the patient trusts, knows values, will respect wishes]. (Examiner should attend to undue influence or coercion.) |

| Q7: | [Ask only if the person names someone who is involved in conflict or abuse, or someone about whom there is concern regarding the agent’s capacity to be an appropriate agent.] Some people are concerned that your family member/friend may not be the best person because. Can you explain to me how you think about that? |

| A: | [Specific to person] |

| Q8: | Do you have to fill out an advance directive? |

| A: | No. |

| Q9: | Why do you want or not want to do it? |

| A: | To have someone to make decisions for me if (or because now) I cannot. (Or person provides reasons why they are not comfortable with it.) |

| Q10: | What happens if your illness gets worse and you are unable to speak for yourself? |

| A: | The person would make decisions for me. |

| Q11: | Who would you choose as your agent? |

| A: | [Specific to person] (Repeats Q4; examiner assess consistency.) |

CONCLUSION

Evaluations of the capacity to appoint a healthcare surrogate are an important area of clinical practice. The incidence of diminished capacity to make healthcare decisions will continue to grow in our aging society along with the increasing prevalence of dementia and other factors affecting cognition.48 Careful clinical assessment of the capacity to appoint an HCP may consider the patient’s understanding of what it means to give surrogate authority and how that is accomplished with the HCP instrument, as well as the patient’s ability to determine and express a consistent and appropriate choice of agent. The adequacy of the patient’s abilities in these functional areas may be weighed in the context of the risks and benefits of the treatment and proxy situation. As a rule of thumb, any standard for capacity to appoint a healthcare surrogate must also take into account the relative risks and burdens of a stringent, high standard on one hand and a lax standard on the other.

Studies of the capacity to appoint a healthcare surrogate are hampered by the lack of consensus or instruments to reliably measure such capacity. Forensic assessment instruments,44 which articulate legal standards for elements of capacity into questions and associated ratings, such as the MacArthur Competency Assessment Tools,49 facilitate capacity research in that elements of capacity can then be compared with relevant clinical and neuropsychological markers. More development of instruments to assess capacity to execute an advance directive, such as the HCP guidelines,33 as well as questions and frameworks suggested in this article, could be useful to clinicians and will inform additional research. Relevant research methodologies include agreement between two methods of assessing capacity (e.g., two clinicians; a clinician and an instrument), changes in capacity over time (e.g., across disease course), markers of impaired capacity (e.g., diagnostic and neuropsychological correlates), and naturalistic case series that examine clinical, ethical, and legal applications and limitations of HCP. In particular, it will be useful to empirically compare capacity to consent to treatment and capacity to execute an HCP to investigate the similarities and differences. Ongoing collaboration between clinicians, legal professionals, and researchers will further elucidate appropriate methods for assessing capacity to appoint a healthcare surrogate and facilitate optimal clinical care for vulnerable adults.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Boston VA Medical Center and the Boston VA Research Institute (BVARI) for Dr. Moye and the use of facilities and resources at Massachusetts General Hospital for Dr. Weintraub Brendel.

Footnotes

There are no disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Brendel RW, Schouten RA, Levenson JL. In: Legal issues, in American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychosomatic Medicine: Psychiatric Care of the Medically Ill. 2nd. Levenson JL, editor. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2011. pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black BS, Wechsler M, Fogarty L. Decision making for participation in dementia research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uhlmann RF, Pearlmann RA. Perceived quality of life and preferences for life-sustaining treatment in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:495–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brendel RW, Schouten RA. Legal concerns in psychosomatic medicine. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perkins HS. controlling death: the false promise of advance directive. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:51–57. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagerlin A, Schneider C. Enough: the failure of the living will. Hastings Center Rep. 2004;34:30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silveira MJ, Kim SKJ, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1211–1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Bar Association and American Psychological Association Assessment of Capacity in Older Adults Project Working Group. Assessment of Older Adults with Diminished Capacity: A Handbook for Lawyers. Washington, DC: American Bar Association and American Psychological Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1834–1840. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp074045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment. New York, Oxford: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karlawish JHT, Schmitt FA. Why physicians need to become more proficient in assessing their patients’ competency and how they can achieve this. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1014–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burton CZ, Twamley EW, Lee LC, et al. Undetected cognitive impairment and decision-making capacity in patients receiving hospice care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:306–316. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182436987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1635–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812223192504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marson DC, Cody HA, Ingram KK, et al. Neuropsychological predictors of competency in Alzheimer’s disease using a rational reasons legal standard. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:955–959. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540340035011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marson DC, Hawkins L, McInturff B, et al. Cognitive models that predict physician judgments of capacity to consent in mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:458–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marson DC, Ingram KK, Cody HA, et al. Assessing the competency of patients with Alzheimer’s disease under different legal standards. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:949–954. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540340029010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. The MacArthur treatment competency study 1: mental illness and competence to consent to treatment. Law Hum Behav. 1995;19:105–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01499321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990. 42 USC 1395 cc(a); final rule 60 CFR 123 at 33294. Vol. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berg JW, Appelbaum PS, Lidz CW, et al. Informed Consent: Legal Theory and Clinical Practice. New York, Oxford: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glezer A, Weintraub Brendel R. Beyond emergencies: the use of restraints in medical and psychiatric settings. Harv Rev Psych. 2010;18:353–358. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2010.527514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moye J, Karel MJ, Armesto JC. In: Evaluating capacity to consent to treatment, in Forensic Psychology: Emerging Topics and Expanded Roles. Goldstein AM, Hoboken NJ, editors. Wiley; 2007. pp. 260–293. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weintraub Brendel R, Wei MH, Schouten R, et al. An approach to selected legal issues: confidentiality, mandatory reporting, abuse and neglect, informed consent, capacity decisions, boundary issues, and malpractice claims. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:1229–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim S, Appelbaum PS. The capacity to appoint a proxy and the possibility of concurrent proxy directives. Behav Sci Law. 2006;24:469–478. doi: 10.1002/bsl.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duke v. Kindred Healthcare Operating IW, 7 (Tenn.. Ct. App., 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 25.West’s Ann. Cal. Prob. Code, § 4120 [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMillan 940 A.2d 1027 DC, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown BB, Grigsby J, Kaye K, et al. Mental Capacity: Legal and Medical Aspects of Assessment and Treatment 2. In: Eagan MN, editor. Thomson Reuters West Law. 1997–2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. Uniform Health Decisions Act 1993; [Accessed May 8, 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Health Care Proxies, Mass. Gen. Laws, Ch. 201 D § 2. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Advance Healthcare Directive Amendments, Utah Code Annotated §75–2a. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Advance Directives for Healthcare and Disposition 18 V.S.A. Ch. 231 § 9701(4)(A) 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health, 497 U.S. 261 (United States Supreme Court 1990) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mezey M, Teresi J, Ramsey G, et al. Decision-making capacity to execute a health care proxy: development and testing of guidelines. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:179–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moye J, Karel MJ, Azar A, et al. Capacity to consent to treatment: empirical comparison of three instruments in older adults with and without dementia. Gerontologist. 2004;44:166. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.2.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sansone P, Schmitt L, Nichols J, et al. Determining the capacity of demented nursing home residents to name a health care proxy. Clin Gerontol. 1998;19:35–51. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karel MJ, Moye J, Bank A, et al. Three methods of assessing values for advance care planning: comparing persons with and without dementia. J Aging Health. 2007;19:123–151. doi: 10.1177/0898264306296394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karlawish JH, Casarett DJ, James BD. Alzheimer’s disease patients’ and caregivers’ capacity, competency, and reasons to enroll in an early-phase Alzheimer’s disease clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:2019–2024. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim SY, Caine ED, Currier GW, et al. Assessing the competence of persons with Alzheimer’s disease in providing informed consent for participation in research. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:712–717. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jefferson AL, Lambe S, Moser DJ, et al. Decisional capacity for research participation among individuals with mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1236–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Misra S, Socherman R, Park BS, et al. Influence of mood state on capacity to consent to research in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Dis. 2008;10:303–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer BW, Dunn LB, Depp CA, et al. Decisional capacity to consent to research among patients with bipolar disorder: comparison with schizophrenia patients and healthy subjects. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:689–696. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim S, Karlawish JHT, Kim M, et al. Preservation of the capacity to appoint a proxy decision maker. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:214–220. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Bar Association and American Psychological Association Assessment of Capacity in Older Adults Project Working Group. Assessment of Older Adults with Diminished Capacity: A Handbook for Psychologists. Washington, DC: American Bar Association and American Psychological Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grisso T. Evaluating Competences. 2nd. New York, Plenum: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strauss PJ. The health care proxy: does the patient have the capacity to sign it. Alzheimer’s Association Newsletter. 2006 summer; Available at: http://www.alznyc.org/newsletter/summer2006/16.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabatino CP. The evolution of healthcare advance planning law and policy. Milbank Q. 2010;88:211–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Volicer L, Cantor MD, Derse AR, et al. Advance care planning by proxy for residents of long term care facilities who lack decision-making capacity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:761–767. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alzheimer’s Association. 2011 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. MacArthur Competency Assessment Tool for Treatment (MacCAT-T) Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]