Abstract

Background

Premature cardiac contractions are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Though experts associate premature atrial contractions (PACs) and premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) with caffeine, there are no data to support this relationship in the general population. As certain caffeinated products may have cardiovascular benefits, recommendations against them may be detrimental.

Methods and Results

We studied Cardiovascular Health Study participants with a baseline food frequency assessment, 24‐hour ambulatory electrocardiography (Holter) monitoring, and without persistent atrial fibrillation. Frequencies of habitual coffee, tea, and chocolate consumption were assessed using a picture‐sort food frequency survey. The main outcomes were PACs/h and PVCs/hour. Among 1388 participants (46% male, mean age 72 years), 840 (61%) consumed ≥1 caffeinated product per day. The median numbers of PACs and PVCs/h and interquartile ranges were 3 (1–12) and 1 (0–7), respectively. There were no differences in the number of PACs or PVCs/h across levels of coffee, tea, and chocolate consumption. After adjustment for potential confounders, more frequent consumption of these products was not associated with ectopy. In examining combined dietary intake of coffee, tea, and chocolate as a continuous measure, no relationships were observed after multivariable adjustment: 0.48% fewer PACs/h (95% CI −4.60 to 3.64) and 2.87% fewer PVCs/h (95% CI −8.18 to 2.43) per 1‐serving/week increase in consumption.

Conclusions

In the largest study to evaluate dietary patterns and quantify cardiac ectopy using 24‐hour Holter monitoring, we found no relationship between chronic consumption of caffeinated products and ectopy.

Keywords: arrhythmia, diet, electrophysiology, epidemiology

Subject Categories: Arrhythmias, Electrophysiology, Epidemiology, Diet and Nutrition, Risk Factors

Introduction

Premature cardiac contractions, otherwise known as atrial and ventricular ectopy, are common throughout the general population.1, 2 Previously, these ectopic beats were believed to be harmless in the absence of known cardiovascular disease or symptoms; however, there is now evidence to indicate that premature atrial contractions (PACs) and premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) are associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. PACs are known to initiate paroxysms of atrial fibrillation (AF), and targeted ablation of ectopic foci in the atria can eliminate or significantly reduce AF recurrence.3 In addition, we previously showed that the PAC count is a particularly useful predictor of incident AF in older adults,4 and others have demonstrated that increased PACs in apparently healthy individuals are associated with incident AF, stroke, and death.5 With regard to PVCs, the presence of even one PVC during a 2‐minute ECG has been associated with an increased risk of incident congestive heart failure (CHF), coronary artery disease (CAD) events, and CAD‐related death.6, 7 Additionally, our group has previously demonstrated that a higher frequency of PVCs is associated with an increase in incident CHF and with increased mortality.8 Furthermore, recent evidence from the electrophysiology laboratory has shown that eradication of PVCs via radiofrequency ablation among patients with idiopathic systolic heart failure can normalize ventricular function, suggesting that PVCs alone are sufficient to result in heart failure.9

Although a causal relationship between PACs and AF or PVCs and heart failure cannot be determined by these large epidemiologic studies, extrapolation from data already available from the electrophysiology laboratory has raised interest in the theoretical benefit of prophylactic PAC and PVC ablation.4, 10 However, little is known about modifiable exposures that may reduce or prevent frequent PACs or PVCs.

Patients often associate the symptoms of premature cardiac contractions with emotional stress, physical activity, dietary factors, and caffeine or other stimulant use.11 Though there is little data to support the role of behavioral modifications or trigger avoidance in reducing or preventing premature cardiac contractions, clinicians often instruct patients with any arrhythmia to avoid caffeine intake. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines on the management of supraventricular arrhythmias state that if a patient's history is consistent with premature extra beats, one should review and eliminate potential exacerbating factors, such as caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine.12 Prominent online medical resources for clinicians, such as UpToDate and Medscape, feature similar recommendations for the management of premature beats.13, 14 While none of these sources explicitly refer to the acute versus chronic effects of caffeine on ectopy, they focus on general avoidance in order to avoid triggering arrhythmias. Caffeine is of particular interest because of its known sympathomimetic effects, leading to increased plasma norepinephrine and epinephrine levels15 and, as a result, possibly increasing ectopy. While most observational and experimental studies examining the effect of caffeine intake on arrhythmogenesis have been negative, the majority of them focus on populations known to have increased premature cardiac contractions, arrhythmias such as supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) or ventricular tachycardia (VT), or other heart disease.16, 17, 18, 19 In addition, most of the interventional trials investigating the effects of caffeine or other lifestyle modifications on arrhythmias were performed several decades ago11 and frequently did not use premature cardiac contractions as a primary outcome.18

Recent and growing evidence points to the potential beneficial cardiovascular effects of several common caffeinated products, including coffee,20 chocolate,21 and tea.22 There may therefore be uncertainty in counseling patients regarding consumption of these products, and many patients may reduce their exposure in order to avoid the presumed arrhythmogenic effect at the expense of possible benefits. We thus sought to study the relationship between chronic consumption of these potentially healthy caffeinated products and cardiac ectopy in a community‐based cohort.

Methods

Study Design

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) is a prospective, community‐based cohort study sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Details surrounding eligibility, enrollment, and follow‐up have been previously published.23, 24, 25 In short, 5201 individuals 65 years or older were recruited between 1989 and 1990 from a random sample of Medicare beneficiaries by 4 academic centers (Johns Hopkins University, Wake Forest University, University of Pittsburgh, and University of California, Davis). An additional 687 black participants were recruited between 1992 and 1993. Each center's institutional review committee approved the study, and all individuals gave informed consent. At enrollment, all participants had a medical history, clinic examination, laboratory testing, and 12‐lead ECG performed. Participants were then followed with annual clinic visits and semiannual telephone contact for 10 years, with telephone contact continued every 6 months thereafter.

Study Cohort

A total of 1416 individuals from the initial cohort (those recruited between 1989 and 1990) were randomly selected (from all original‐cohort CHS participants) to undergo 24‐hour ambulatory electrocardiography (Holter) monitoring during their initial assessment and completed the baseline food frequency questionnaire. Participants with persistent AF throughout the Holter period were excluded, leaving 1388 individuals for analysis.

Dietary Assessment

At baseline, participants completed a picture‐sort exercise derived from the 99‐item National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaire. Individuals were given a set of cards naming and showing a particular food or beverage. They were then asked to sort the cards into 5 marked categories based on how often they on average consumed that food over the past 12 months. The picture‐sort approach used in CHS was validated against 6 detailed 24‐hour dietary recall interviews spaced 1‐month apart and found to be as accurate as more conventional, quantitative methods of dietary assessment.26, 27 Caffeinated coffee (in contrast to decaffeinated coffee), tea, and chocolate were the 3 items from the questionnaire included in this study. When describing “chronic consumption” of caffeinated products, we are referring to the average frequency of consumption over the past 12 months.

Assessment of Ectopy and Arrhythmia

Holter data were analyzed at the Washington University School of Medicine Heart Rate Variability Laboratory using a MARS 8000 Holter scanner (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) and manually reviewed to ensure accuracy. The number of supraventricular ectopic beats, or PACs, per hour and number of ventricular ectopic beats, or PVCs, per hour were recorded throughout the duration of Holter monitoring. SVT and VT episodes were evaluated as the total number of discrete episodes (or “runs” defined as 3 or more consecutive beats) during Holter monitoring.

Covariate Ascertainment

Self‐identified race was categorized as white, black, and other. Self‐identified sex was classified as male or female. Self‐reported income, defined as total combined family income before taxes, was categorized into 3 groups: <$12 000, $12 000 to 34 999, and ≥$35 000. Self‐reported education level was categorized into 5 groups: high school or less, vocational school, some college, 4 years of college, and postgraduate education. Body mass index was calculated from baseline height and weight measurements. A measure of daily caloric intake was calculated from the picture‐sort food frequency questionnaire. Diabetes mellitus was defined as reported use of an antihyperglycemic medication at baseline or a fasting glucose level of ≥126 mmol/L. Smoking status was defined as never, past, or current. Participants reported their usual frequency of consumption of beer, wine, and liquor, and the usual number of servings of each drink on each occasion, from which total weekly alcohol consumption was calculated. Hypertension was defined as either a reported history of physician‐diagnosed hypertension plus use of antihypertensive medications, systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg, or diastolic pressure of ≥90 mm Hg. AF was defined as a reported history of AF, AF on baseline 12‐lead ECG, or AF detected on Holter. CHF and myocardial infarction (MI) were identified by participant self‐report and were confirmed by medical record verification. CAD was defined as angina, previous MI, previous coronary artery bypass graft surgery, or previous angioplasty.25 Information regarding prescription medications used in the preceding 2 weeks was collected at baseline directly from prescription bottles, including use of β‐blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, class I antiarrhythmics, and class III antiarrhythmics.23

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables with normal distribution are presented as means± SD and were compared using the Student t test. Non‐normally distributed continuous variables are presented as medians with interquartile ranges and were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The association between categorical variables was determined using the χ2 test.

Dietary intake for coffee, tea, and chocolate were analyzed as both categorical and numeric variables. To convert from self‐reported categories of consumption to a numeric measurement, we estimated the average weekly consumption per category. Specifically, the categories of never, 5 to 10 times per year, 1 to 3 times per month, 1 to 4 times per week, and almost every day were transformed to 0, 0.144, 0.5, 2.5, and 6 servings per week, respectively, by approximating the midpoint of the frequency category, as has been done previously.28 In addition, from these calculations we generated a variable to represent total weekly consumption of coffee, tea, and chocolate.

Linear regression was used to examine the relationship between consumption of caffeinated products and the log‐transformed numbers of PACs, PVCs, SVT, and VT on Holter monitoring. Frequency of consumption was analyzed as both a categorical and a continuous variable. Outcomes (PACs, PVCs, SVT, and VT) were natural log‐transformed to meet model normality assumptions, after adding 0.01 to the counts so that participants with zero counts were retained in the analysis. Regression coefficients for caffeine consumption were back‐transformed using the formula 100×[exp(ß)−1] and interpreted as percent changes in outcome frequency per unit increase in the predictor. Multivariable linear regression was performed to adjust for potential confounding. Covariates added to these models included age, sex, race, income, education, body mass index, daily caloric intake, smoking status, number of alcoholic drinks per week, diabetes, hypertension, CAD, AF, CHF, and use of β‐blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, class I antiarrhythmics, and class III antiarrhythmics. In addition, an analysis was performed adjusting for potential confounders previously associated with AF, specifically tuna and broiled or baked fish consumption29 and markers of physical activity (number of blocks walked, walking pace, total kilocalories of physical activity, and exercise intensity).30 We also performed analyses in which we adjusted for consumption of other caffeinated products (ie, in examining coffee intake we adjusted for tea and chocolate intake).

We checked the residuals for normality, equal variance across categories, and influential points and found no important violations, indicating that our models met standard assumptions. Given the nature of our outcomes, we also modeled our data using negative binomial regression and found no meaningful differences as compared to multivariate linear regression. Finally, we tested for the interaction between cardiovascular disease (defined as the presence of diabetes, hypertension, CAD, CHF, or AF at baseline) and caffeine on the risk of cardiac ectopy.

Data were analyzed using Stata 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). A 2‐tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 1416 CHS participants from the original cohort had 24‐hour Holter monitoring during their initial assessment and completed the baseline food frequency questionnaire. Of those, 28 individuals were excluded on the basis of persistent AF. Greater than 60% of participants reported consuming on average one or more servings of coffee, tea, or chocolate per day. The baseline characteristics of participants stratified by consumption of caffeinated products are summarized in Table 1. Those who consumed at least one serving of a caffeinated product per day were more often women and drank more alcohol; there were no other significant differences observed.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Cardiovascular Health Study Participants by Consumption of Caffeinated Products

| <1 Serving Per Day (n=548) | ≥1 Servings Per Day (n=840) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Mean age±SD, y | 72.2±5.1 | 71.7±4.8 | 0.08 |

| Male, n (%) | 274 (50.0) | 371 (44.2) | 0.03 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.21 | ||

| White | 517 (94.3) | 800 (95.2) | |

| Black | 29 (5.3) | 34 (4.1) | |

| Other | 2 (0.4) | 6 (0.71) | |

| Income, n (%) | 0.90 | ||

| <$12 000 | 103 (20.0) | 161 (20.0) | |

| $12 000 to $34 999 | 278 (53.9) | 442 (54.9) | |

| ≥$35 000 | 135 (26.2) | 202 (25.1) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.49 | ||

| High school or less | 300 (54.8) | 448 (53.3) | |

| Vocational school | 50 (9.1) | 76 (9.1) | |

| Some college | 74 (13.5) | 143 (17.0) | |

| 4 years of college | 62 (11.3) | 91 (10.8) | |

| Postgraduate | 61 (11.2) | 82 (9.8) | |

| Mean BMI+SD, kg/m2 | 26.8±4.2 | 26.6±4.2 | 0.36 |

| Habits | |||

| Mean caloric intake ±SD, kcal | 1771.0±636.5 | 1885.8±676.6 | >0.99 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.12 | ||

| Never smoker | 262 (47.8) | 367 (43.7) | |

| Past smoker | 245 (44.7) | 385 (45.9) | |

| Current smoker | 41 (7.5) | 87 (10.4) | |

| Median number of alcoholic drinks per week (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | <0.01 |

| Medical history | |||

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 82 (15.0) | 129 (15.4) | 0.83 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 304 (55.5) | 456 (54.4) | 0.70 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 118 (21.5) | 161 (19.2) | 0.28 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 6 (1.1) | 13 (1.6) | 0.50 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 18 (3.3) | 25 (3.0) | 0.75 |

| Medications | |||

| β‐Blocker, n (%) | 80 (14.6) | 115 (13.7) | 0.63 |

| Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | 55 (10.1) | 95 (11.3) | 0.46 |

| Digoxin, n (%) | 39 (7.1) | 50 (6.0) | 0.38 |

| Class I antiarrhythmic, n (%) | 22 (4.0) | 27 (3.2) | 0.43 |

| Class III antiarrhythmic, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 0.25 |

Values are reported as mean±SD, median (IQR), or number (percentage). BMI indicates body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

In unadjusted analyses, there were no statistically significant differences in the number of PACs/h, PVCs/h, SVT runs, or VT runs across levels of habitual coffee, tea, and chocolate consumption (Table 2). For instance, focusing on coffee and PACs, the median number of PACs and interquartile range among the every‐day drinkers was 3 (1–11) compared with 2 (1–11) among the never drinkers. Similarly, median PACs was consistently approximately 3, while median number of PVCs was consistently about 1, regardless of the quantity of caffeinated products consumed.

Table 2.

Cardiac Ectopy and Arrhythmia According to Consumption of Caffeinated Products

| Number of PACs/H | Number of PVCs/H | Number of SVT Runs in 24 Hours | Number of VT Runs in 24 Hours* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee | ||||

| Never (n=448) | 2 (1–11) | 1 (0–7.5) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–106) |

| 5 to 10 times per year (n=84) | 4 (2–21.5) | 1 (0–9.5) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) |

| 1 to 3 times per month (n=103) | 3 (1–24) | 1 (0–7) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–13) |

| 1 to 4 times per week (n=133) | 3 (1–14) | 1 (0–8) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–76) |

| Almost every day (n=620) | 3 (1–11) | 1 (0–7) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–100) |

| P value | 0.28 | 0.86 | 0.22 | 0.57 |

| Tea | ||||

| Never (n=298) | 3 (1–12) | 1 (0–8) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–106) |

| 5 to 10 times per year (n=161) | 4 (1–17) | 1 (0–8) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–29) |

| 1 to 3 times per month (n=269) | 3 (1–15) | 1 (0–10) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–19) |

| 1 to 4 times per week (n=309) | 3 (1–11) | 1 (0–5) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–100) |

| Almost every day (n=347) | 3 (1–11) | 0 (0–6) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–53) |

| P value | 0.57 | 0.32 | 0.90 | 0.13 |

| Chocolate | ||||

| Never (n=361) | 3 (1–12) | 1 (0–7) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–106) |

| 5 to 10 times per year (n=363) | 3 (1–16) | 1 (0–7) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–14) |

| 1 to 3 times per month (n=420) | 2.5 (1–12) | 1 (0–8) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–100) |

| 1 to 4 times per week (n=202) | 3 (1–11) | 1 (0–7) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–18) |

| Almost every day (n=41) | 2 (1–5) | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) |

| P value | 0.71 | 0.87 | 0.72 | 0.76 |

PAC indicates premature atrial contraction; PVC, premature ventricular contraction; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Values are reported as median (interquartile range), with the exception of number of VT runs (*), which is reported as median (overall range) given an interquartile range of (0–0) for all subgroups.

In adjusted analyses, there were similarly no statistically significant associations between frequencies of coffee, tea, or chocolate consumption and PACs/h, PVCs/h, or number of SVT runs (Table 3). The consumption of coffee 1 to 4 times per week (versus no coffee) and the consumption of tea 5 to 10 times per year (versus no tea) were each associated with a greater number of runs of VT. Tests for trends across levels of consumption failed to reveal any statistically significant linear or nonlinear trends for all 4 outcomes.

Table 3.

Adjusted Associations Between Frequency of Caffeinated Product Consumption and Cardiac Ectopy and Arrhythmia

| PACs/H | PVCs/H | SVT Runs in 24 Hours | VT Runs in 24 Hours | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Coffee | ||||||||

| Never | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 5 to 10 times per year | 0.58 (−0.12, 1.27) | 0.11 | 0.54 (−0.38, 1.47) | 0.25 | 0.70 (−0.05, 1.44) | 0.07 | 0.33 (−0.01, 0.67) | 0.06 |

| 1 to 3 times per month | 0.44 (−0.18, 1.05) | 0.16 | −0.07 (−0.89, 0.75) | 0.87 | −0.14 (−0.81, 0.52) | 0.67 | −0.11 (−0.412, 0.19) | 0.46 |

| 1 to 4 times per week | 0.35 (−0.24, 0.93) | 0.25 | 0.34 (−0.43, 1.12) | 0.39 | 0.24 (−0.39, 0.87) | 0.46 | 0.29 (0.01, 0.58) | 0.04 |

| Almost every day | 0.19 (−0.18, 0.55) | 0.31 | 0.00 (−0.48, 0.49) | 0.99 | 0.11 (−0.29, 0.50) | 0.59 | 0.03 (−0.14, 0.21) | 0.71 |

| a P value for trend | 0.81 | 0.70 | 0.81 | 0.94 | ||||

| Tea | ||||||||

| Never | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 5 to 10 times per year | 0.30 (−0.26 0.87) | 0.30 | 0.46 (−0.29, 1.20) | 0.23 | 0.28 (−0.32, 0.89) | 0.36 | 0.29 (0.02, 0.56) | 0.04 |

| 1 to 3 times per month | 0.34 (−0.15, 0.83) | 0.17 | 0.58 (−0.06, 1.23) | 0.08 | 0.28 (−0.25, 0.80) | 0.30 | 0.05 (−0.18, 0.29) | 0.65 |

| 1 to 4 times per week | 0.16 (−0.32, 0.63) | 0.52 | 0.15 (−0.48, 0.77) | 0.64 | 0.02 (−0.49, 0.52) | 0.95 | 0.17 (−0.06, 0.39) | 0.15 |

| Almost every day | 0.09 (−0.37, 0.55) | 0.70 | 0.10 (−0.51, 0.71) | 0.75 | 0.09 (−0.41, 0.58) | 0.73 | 0.14 (−0.07, 0.36) | 0.20 |

| a P value for trend | 0.94 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.75 | ||||

| Chocolate | ||||||||

| Never | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 5 to 10 times per year | 0.15 (−0.29, 0.58) | 0.51 | −0.05 (−0.63, 0.53) | 0.86 | 0.05 (−0.42, 0.52) | 0.83 | −0.08 (−0.29, 0.13) | 0.45 |

| 1 to 3 times per month | −0.09 (−0.51, 0.33) | 0.67 | 0.12 (−0.44, 0.68) | 0.68 | 0.01 (−0.45, 0.46) | 0.98 | 0.00 (−0.21, 0.20) | 0.97 |

| 1 to 4 times per week | 0.08 (−0.45, 0.60) | 0.77 | −0.23 (−0.92, 0.47) | 0.53 | 0.12 (−0.44, 0.69) | 0.67 | 0.06 (−0.20, 0.31) | 0.65 |

| Almost every day | −0.33 (−1.29, 0.63) | 0.50 | −0.54 (−1.81, 0.72) | 0.40 | 0.13 (−0.89, 1.16) | 0.80 | −0.07 (−0.54, 0.39) | 0.76 |

| a P value for trend | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.82 | 0.89 | ||||

Regression coefficients, 95% CIs, and P values for log‐transformed outcomes after adjustment for clinic site, age, sex, race, income, education level, body mass index, dietary caloric intake, smoking status, number of alcoholic drinks per week, diabetes, hypertension are shown, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, and use of β‐blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, class I antiarrhythmics, and class III antiarrhythmics.

P value for the test of linear trend.

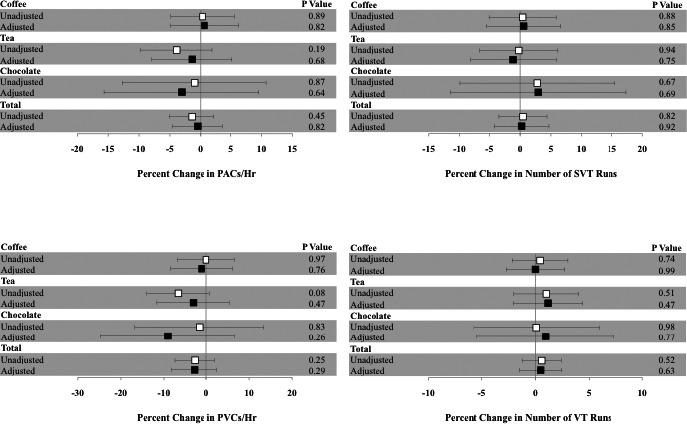

In examining dietary intake of coffee, tea, and chocolate as continuous measures and as a combined measure of total average consumption, we found no statistically significant relationships between weekly servings of caffeinated products and cardiac ectopy, SVT, and VT (Figure). We observed a non–statistically significant estimated 0.48% decrease in PACs/h (95% CI −4.60 to 3.64) as well as a non–statistically significant estimated 2.87% decrease in PVCs/h (95% CI −8.18 to 2.43) for every 1 serving per week increase in regular consumption.

Figure 1.

Estimated percent increase in cardiac ectopy for a serving per week increase in coffee, tea, or chocolate consumption. The unadjusted (white square) and adjusted (black square) estimates shown are after adjustment for clinic site, age, sex, race, income, education level, body mass index, dietary caloric intake, smoking status, number of alcoholic drinks per week, diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, and use of β‐blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, class I antiarrhythmics, and class III antiarrhythmics. Y error bars denote 95% CIs. PAC indicates premature atrial contraction; PVC, premature ventricular contraction; SVT, number of runs of supraventricular tachycardia; VT, number of runs of ventricular tachycardia.

Additional analyses adjusting for factors associated with AF, such as fish consumption and physical activity, did not meaningfully alter the results. Similarly, adjusting for the effects of other caffeinated product consumption did not reveal any further associations between coffee, tea, or chocolate and cardiac ectopy. No statistically significant interactions between the presence of cardiovascular disease (defined as the presence of diabetes, hypertension, CAD, CHF, or AF at baseline) and caffeine on the risk of PACs, PVCs, SVT, or VT were observed (P=0.17, 0.13, 0.37, and 0.77, respectively).

Discussion

In an investigation of nearly 1400 older adults, we found no evidence that the frequency of habitual coffee, tea, or chocolate consumption was associated with cardiac ectopy before or after multivariable adjustment. This absence of association between caffeine and arrhythmias did not change whether caffeine was treated as a continuous or a categorical predictor.

Premature cardiac contractions are a common, often asymptomatic condition. However, given the growing evidence linking both PACs and PVCs to increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, it is important we further our understanding of risk factors for ectopy. Increased PACs, even among healthy individuals, have been associated with incident AF, stroke, and death.5 Furthermore, the presence of PVCs in those free of heart disease has been associated with an increased risk of incident heart failure, CAD events, and CAD‐related death.6, 7 Our study is the first to examine chronic consumption of caffeinated products and cardiac ectopy in a community‐based population using 24‐hour Holter monitoring to directly assess PAC and PVC counts. Prior studies have focused on populations with previous diagnoses of symptomatic ventricular ectopy, arrhythmia, or MI, making it difficult to generalize their findings to other populations.16, 17, 18, 19 Furthermore, our study used a validated approach to assessing food frequencies to approximate a person's typical consumption, as compared to other studies that have administered predetermined caffeine doses regardless of a person's average consumption.17, 18, 31

Previous research examining the role of caffeine in ectopy and arrhythmia largely supports our negative findings. Though caffeine consumption has long been related to cardiac ectopy and arrhythmias by anecdote and biological plausibility, few studies have demonstrated any relationship. Several interventional studies have failed to demonstrate an effect of caffeine intake on ectopy and arrhythmias. One of the earliest studies was a randomized controlled trial of a 6‐week lifestyle intervention among 81 healthy men with persistent PVCs.11 Participants were randomly allocated to a control group where they were asked to maintain their usual life habits, to an intervention group where they were asked to abstain from caffeine‐containing compounds (including coffee, tea, cola beverages, and chocolate), quit smoking, limit alcohol intake, and obtain sufficient sleep, or to a second intervention group consisting of the prior modifications in addition to a supervised physical conditioning program. The intervention had no significant effect on the occurrence of frequency of PVCs.

In another interventional study, researchers gave participants with a history of malignant ventricular arrhythmias an oral caffeine load of 275 mg, similar to that found in 2 to 3 cups of coffee, and performed electrophysiological testing 1 hour prior to and 1 hour after coffee administration.18 They found that caffeine did not affect the inducibility or severity of arrhythmias in these patients. Similarly, another group of researchers performed a study of 50 consecutive patients with malignant ventricular arrhythmias, administering decaffeinated coffee versus decaffeinated coffee mixed with 200 mg of caffeine, and monitored continuous electrocardiographic recordings during a 30‐minute control period and a 3‐hour observation period, including an hourly bicycle test.17 They found no difference in the number of PVCs, rates of ventricular couplets, or salvos of VT between the 2 groups, concluding that there was no evidence to suggest that a modest dose of caffeine is arrhythmogenic, even in patients at high risk. Furthermore, high‐dose caffeine administered to a group of 34 healthy adults also failed to increase ectopy, arrhythmias, or even heart rate during a 24‐hour Holter monitor period.31 Finally, a study of over 3000 patients hospitalized for cardiac arrhythmias actually found an inverse relationship between reported coffee and caffeine intake and hospitalization for arrhythmias, suggesting it is unlikely that moderate caffeine intake increases arrhythmia risk.32

Despite a lack of evidence for caffeine abstention or moderation in reducing premature cardiac contractions and arrhythmias, clinicians and treatment guidelines often recommend that such patients avoid caffeine. For example, published guidelines on the management of supraventricular arrhythmias advocate reviewing and eliminating potential exacerbating factors, such as caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine.12 Popular resources for clinicians, including UpToDate and Medscape, offer similar suggestions for the management of premature beats.13, 14

Coffee is among the most commonly consumed beverages in the United States20 and is the main source of caffeine intake among adults.33 The biological impact of coffee may be substantial and is not limited to the effects of caffeine. Regular coffee consumption has been associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and other cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity and depression.20 Furthermore, large observational studies have found that habitual coffee drinkers have lower rates of CAD and of cardiovascular and all‐cause mortality.34, 35 However, not all evidence favors a protective effect of coffee on CAD. Specifically, one case–control study found an increased risk of MI in the hour after coffee consumption.36 Interestingly, this effect was stronger in light/occasional coffee drinkers (<1 cup/day) as compared to moderate coffee drinkers (2–3 cups/day) and absent among heavy coffee drinkers (≥4 cups/day). In considering these results, however, it is important to recognize that recall bias may have played a role, given that participants were interviewed immediately post‐MI regarding their behaviors prior to the event. In addition, chocolate and tea are caffeine‐containing compounds that have also been postulated to have cardioprotective effects because of their high flavonoid content.21 Flavonoids boast antioxidant properties and have been shown to increase nitric oxide availability inducing vasodilation, which possibly accounts for the described protective effects of cocoa consumption on the vascular endothelium.37 Short‐term administration of dark chocolate, which has a higher flavonoid content, has been shown to lower blood pressure in both hypertensive and healthy subjects.38, 39 In addition, studies have demonstrated that chocolate and tea consumption bear inverse relationships to prevalent and incident CAD, respectively.21, 22

Our results support a long history of data from both experimental and observational trials indicating that moderate consumption of caffeine is not associated with cardiac ectopy and extend that evidence from predominately arrhythmia patients to a community‐based cohort. Findings from this study suggest that the regular consumption of specific caffeinated products, in aggregate or alone, is not associated with cardiac ectopy in the general population. Though we observed an association between 2 isolated frequencies of coffee and tea intake and number of VT runs, these results were not in line with the general observations, none of the unadjusted analyses were statistically significant, and the multivariable adjusted regression coefficients showed no trend towards increased or decreased VT across increasing categories of coffee and tea consumption. While we cannot exclude a true effect between these very specific amounts of caffeinated product consumption and VT, we suspect these results are likely false positives due to multiple hypothesis testing. In addition, analyzing coffee and tea consumption as continuous measures did not reveal any significant relationships with VT.

Several limitations of our study must be acknowledged. First, while insufficient power is a common explanation for negative results, it is important to emphasize that even at the extremes of the 95% CI there was no evidence of a clinically large effect. We also relied on self‐report for the quantification of caffeinated product consumption. While self‐report may be less accurate than other methods of tracking dietary intake, food frequency questionnaires are commonly used in dietary assessment, and the picture‐sort approach used in CHS has been previously validated.26, 27 Furthermore, food frequency questionnaires allow for the assessment of habitual dietary patterns over extended periods of time. A concern is that these data only give us insight into average consumption and not what participants ate immediately prior to and during the Holter monitoring. While this may be a disadvantage, our study remains unique in its rigorous, validated assessment of dietary intake combined with 24‐hour ECG monitoring, and it would appear unlikely that typical dietary patterns would have changed substantially on the day of the Holter in most participants. In addition, it is improbable that recall bias affected our dietary assessment, given that participants were unaware of how the dietary information would later be used and that those who received baseline Holter monitoring were randomly selected from the total study population. Other limitations surrounding the dietary assessment include the absence of total caffeine quantification and specifically data on caffeinated soda consumption. Nonetheless, in order for soda intake to confound our negative findings, its effect would have to be greater than that of coffee, tea, and chocolate combined in increasing cardiac ectopy, which seems unlikely. Another shortcoming of the caffeine assessment is that it does not discriminate among amounts of daily consumption. Therefore, we are only able to conclude that in general, consuming caffeinated products every day is not associated with having increased ectopy or arrhythmia but cannot specify a particular amount per day. It is possible that those participants most prone to ectopy in the setting of caffeine may have already reduced or eliminated their caffeine intake. However, it is well established that arrhythmias are often asymptomatic,40, 41, 42 and this limitation would likely only apply to participants with symptomatic ectopy. Finally, as we examined several categories of consumption for coffee, tea, and chocolate and 4 different electrocardiographic outcomes, there is a possibility that false positive results may arise due to multiple comparisons. However, given our generally consistently negative findings regarding caffeine and ectopy, this in fact strengthens our confidence that there were no real positive associations.

In the largest cohort study to ascertain dietary data and quantify cardiac ectopy using 24‐hour Holter monitoring and the first to do so in a community‐based cohort, we found no evidence that chronic consumption of caffeinated products was associated with more PACs or PVCs. Our findings suggest that clinical recommendations advising against the regular consumption of caffeinated products to prevent cardiac ectopy and arrhythmia should be reconsidered. However, whether acute consumption of these caffeinated products affects cardiac ectopy requires further study.

Sources of Funding

This research was made possible in part by the Clinical and Translational Research Fellowship Program (CTRFP), a program of UCSF's Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) that is sponsored in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF‐CTSI Grant Number TL1 TR000144 and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (DDCF). This research was also made possible by The Joseph Drown Foundation (to Marcus) and supported by contracts HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, N01HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086, and grant U01HL080295 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Additional support was provided by R01AG023629 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at CHS‐NHLBI.org. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, UCSF, or the DDCF.

Disclosures

Dr Marcus has received research support from the NIH, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, SentreHeart, Medtronic, and Pfizer and is a consultant for and holds equity in InCarda.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002503 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002503)

References

- 1. Manolio TA, Furberg CD, Rautaharju PM, Siscovick D, Newman AB, Borhani NO, Gardin JM, Tabatznik B. Cardiac arrhythmias on 24‐h ambulatory electrocardiography in older women and men: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:916–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Simpson RJ Jr, Cascio WE, Schreiner PJ, Crow RS, Rautaharju PM, Heiss G. Prevalence of premature ventricular contractions in a population of African American and white men and women: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J. 2002;143:535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, Garrigue S, Le Mouroux A, Le Metayer P, Clementy J. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dewland TA, Vittinghoff E, Mandyam MC, Heckbert SR, Siscovick DS, Stein PK, Psaty BM, Sotoodehnia N, Gottdiener JS, Marcus GM. Atrial ectopy as a predictor of incident atrial fibrillation: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:721–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Binici Z, Intzilakis T, Nielsen OW, Kober L, Sajadieh A. Excessive supraventricular ectopic activity and increased risk of atrial fibrillation and stroke. Circulation. 2010;121:1904–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Massing MW, Simpson RJ Jr, Rautaharju PM, Schreiner PJ, Crow R, Heiss G. Usefulness of ventricular premature complexes to predict coronary heart disease events and mortality (from the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities cohort). Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1609–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agarwal SK, Simpson RJ Jr, Rautaharju P, Alonso A, Shahar E, Massing M, Saba S, Heiss G. Relation of ventricular premature complexes to heart failure (from the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities [ARIC] Study). Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:105–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dukes JW, Dewland TA, Vittinghoff E, Mandyam MC, Heckbert SR, Siscovick DS, Stein PK, Psaty BM, Sotoodehnia N, Gottdiener JS, Marcus GM. Ventricular ectopy as a predictor of heart failure and death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bogun F, Crawford T, Reich S, Koelling TM, Armstrong W, Good E, Jongnarangsin K, Marine JE, Chugh A, Pelosi F, Oral H, Morady F. Radiofrequency ablation of frequent, idiopathic premature ventricular complexes: comparison with a control group without intervention. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:863–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen T, Koene R, Benditt DG, Lu F. Ventricular ectopy in patients with left ventricular dysfunction: should it be treated? J Cardiac Fail. 2013;19:40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. DeBacker G, Jacobs D, Prineas R, Crow R, Vilandre J, Kennedy H, Blackburn H. Ventricular premature contractions: a randomized non‐drug intervention trial in normal men. Circulation. 1979;59:762–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blomstrom‐Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Camm AJ, Campbell WB, Haines DE, Kuck KH, Lerman BB, Miller DD, Shaeffer CW Jr, Stevenson WG, Tomaselli GF, Antman EM, Smith SC Jr, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gibbons RJ, Gregoratos G, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Jacobs AK, Russell RO Jr, Priori SG, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Burgos EF, Cowie M, Deckers JW, Garcia MA, Klein WW, Lekakis J, Lindahl B, Mazzotta G, Morais JC, Oto A, Smiseth O, Trappe HJ. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias–executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology committee for practice guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias) developed in collaboration with NASPE‐Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1493–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ventricular Premature Beats. UpToDate. Available at: http://www-uptodate-com.ucsf.idm.oclc.org/contents/ventricular-premature-beats. Accessed November 10, 2014.

- 14. Ventricular Premature Complexes Treatment & Management. Medscape. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/158939-treatment#a1130. Accessed November 10, 2014.

- 15. Robertson D, Frolich JC, Carr RK, Watson JT, Hollifield JW, Shand DG, Oates JA. Effects of caffeine on plasma renin activity, catecholamines and blood pressure. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Silletta MG, Marfisi R, Levantesi G, Boccanelli A, Chieffo C, Franzosi M, Geraci E, Maggioni AP, Nicolosi G, Schweiger C, Tavazzi L, Tognoni G, Marchioli R. Coffee consumption and risk of cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction: results from the GISSI (Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'Infarto miocardico)‐Prevenzione trial. Circulation. 2007;116:2944–2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graboys TB, Blatt CM, Lown B. The effect of caffeine on ventricular ectopic activity in patients with malignant ventricular arrhythmia. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:637–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chelsky LB, Cutler JE, Griffith K, Kron J, McClelland JH, McAnulty JH. Caffeine and ventricular arrhythmias. An electrophysiological approach. JAMA. 1990;264:2236–2240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lemery R, Pecarskie A, Bernick J, Williams K, Wells GA. A prospective placebo controlled randomized study of caffeine in patients with supraventricular tachycardia undergoing electrophysiologic testing. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015;26:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. O'Keefe JH, Bhatti SK, Patil HR, DiNicolantonio JJ, Lucan SC, Lavie CJ. Effects of habitual coffee consumption on cardiometabolic disease, cardiovascular health, and all‐cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1043–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Djousse L, Hopkins PN, North KE, Pankow JS, Arnett DK, Ellison RC. Chocolate consumption is inversely associated with prevalent coronary heart disease: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study. Clin Nutr. 2011;30:182–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Koning Gans JM, Uiterwaal CS, van der Schouw YT, Boer JM, Grobbee DE, Verschuren WM, Beulens JW. Tea and coffee consumption and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1665–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, Kuller LH, Manolio TA, Mittelmark MB, Newman A, O'Leary DH, Psaty B, Rautaharju P, Tracy RP, Weiler PG. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Crowley PM, Cruise RG, Theroux S. Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:278–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D, Burke GL, Kittner SJ, Mittelmark M, Price TR, Rautaharju PM, Robbins J. Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kumanyika SK, Tell GS, Shemanski L, Martel J, Chinchilli VM. Dietary assessment using a picture‐sort approach. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:1123S–1129S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kumanyika S, Tell GS, Fried L, Martel JK, Chinchilli VM. Picture‐sort method for administering a food frequency questionnaire to older adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96:137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kumanyika S, Tell GS, Shemanski L, Polak J, Savage PJ. Eating patterns of community‐dwelling older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1994;4:404–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mozaffarian D, Psaty BM, Rimm EB, Lemaitre RN, Burke GL, Lyles MF, Lefkowitz D, Siscovick DS. Fish intake and risk of incident atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2004;110:368–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mozaffarian D, Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Siscovick D. Physical activity and incidence of atrial fibrillation in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2008;118:800–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Newcombe PF, Renton KW, Rautaharju PM, Spencer CA, Montague TJ. High‐dose caffeine and cardiac rate and rhythm in normal subjects. Chest. 1988;94:90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Klatsky AL, Hasan AS, Armstrong MA, Udaltsova N, Morton C. Coffee, caffeine, and risk of hospitalization for arrhythmias. Perm J. 2011;15:19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mitchell DC, Knight CA, Hockenberry J, Teplansky R, Hartman TJ. Beverage caffeine intakes in the U.S. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;63:136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lopez‐Garcia E, van Dam RM, Li TY, Rodriguez‐Artalejo F, Hu FB. The relationship of coffee consumption with mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:904–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu JN, Ho SC, Zhou C, Ling WH, Chen WQ, Wang CL, Chen YM. Coffee consumption and risk of coronary heart diseases: a meta‐analysis of 21 prospective cohort studies. Int J Cardiol. 2009;137:216–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Baylin A, Hernandez‐Diaz S, Kabagambe EK, Siles X, Campos H. Transient exposure to coffee as a trigger of a first nonfatal myocardial infarction. Epidemiology. 2006;17:506–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fisher ND, Hughes M, Gerhard‐Herman M, Hollenberg NK. Flavanol‐rich cocoa induces nitric‐oxide‐dependent vasodilation in healthy humans. J Hypertens. 2003;21:2281–2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grassi D, Lippi C, Necozione S, Desideri G, Ferri C. Short‐term administration of dark chocolate is followed by a significant increase in insulin sensitivity and a decrease in blood pressure in healthy persons. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:611–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Taubert D, Berkels R, Roesen R, Klaus W. Chocolate and blood pressure in elderly individuals with isolated systolic hypertension. JAMA. 2003;290:1029–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rienstra M, Vermond RA, Crijns HJ, Tijssen JG, Van Gelder IC, Investigators R. Asymptomatic persistent atrial fibrillation and outcome: results of the RACE study. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:939–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Flaker GC, Belew K, Beckman K, Vidaillet H, Kron J, Safford R, Mickel M, Barrell P. Asymptomatic atrial fibrillation: demographic features and prognostic information from the Atrial Fibrillation Follow‐up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study. Am Heart J. 2005;149:657–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yokokawa M, Kim HM, Good E, Chugh A, Pelosi F, Alguire C, Armstrong W, Crawford T, Jongnarangsin K, Oral H, Morady F, Bogun F. Relation of symptoms and symptom duration to premature ventricular complex‐induced cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:92–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]