ABSTRACT

CotG is an abundant protein initially identified as an outer component of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. It has an unusual structure characterized by several repeats of positively charged amino acids that are probably the outcome of multiple rounds of gene elongation events in an ancestral minigene. CotG is not highly conserved, and its orthologues are present in only two Bacillus and two Geobacillus species. In B. subtilis, CotG is the target of extensive phosphorylation by a still unidentified enzyme and has a role in the assembly of some outer coat proteins. We report now that most spore-forming bacilli contain a protein not homologous to CotG of B. subtilis but sharing a central “modular” region defined by a pronounced positive charge and randomly coiled tandem repeats. Conservation of the structural features in most spore-forming bacilli suggests a relevant role for the CotG-like protein family in the structure and function of the bacterial endospore. To expand our knowledge on the role of CotG, we dissected the B. subtilis protein by constructing deletion mutants that express specific regions of the protein and observed that they have different roles in the assembly of other coat proteins and in spore germination.

IMPORTANCE CotG of B. subtilis is not highly conserved in the Bacillus genus; however, a CotG-like protein with a modular structure and chemical features similar to those of CotG is common in spore-forming bacilli, at least when CotH is also present. The conservation of CotG-like features when CotH is present suggests that the two proteins act together and may have a relevant role in the structure and function of the bacterial endospore. Dissection of the modular composition of CotG of B. subtilis by constructing mutants that express only some of the modules has allowed a first characterization of CotG modules and will be the basis for a more detailed functional analysis.

INTRODUCTION

Bacillus subtilis is the model system for the study of endospore-forming bacteria. The processes of spore formation and germination and also endospore (spore) structure have all been studied in detail in B. subtilis and then confirmed in other species. Spore formation starts when cell growth is restricted by nutrient starvation or other harsh environmental conditions (1, 2). The first morphological step of spore formation is asymmetric cell division that produces a large mother cell and a small forespore. The mother cell contributes to forespore maturation and undergoes autolysis at the end of the process, allowing the release of the mature spore (1, 2). The spore is stable and resistant to conditions that would be lethal for most other cells. Spores survive for extended periods of time in the absence of water and nutrients, in extremes of heat and pH, and in the presence of UV radiation, as well as after exposure to solvents, hydrogen peroxide, and lytic enzymes (3, 4). The spore is, however, able to sense the environment and respond to the presence of water and nutrients, generating a vegetative cell that is able to grow and, eventually, resporulate (5).

The resistance properties of the spore are due to its unusual structure. The dehydrated cytoplasm, containing a copy of the chromosome, is surrounded by a series of protective layers. A peptidoglycan cortex is the first shell, the encasement layer, and is surrounded by a multilayered protein coat and finally a thin crust (6). The coat and crust are together composed of at least 70 different proteins and glycoproteins. Several coat and crust proteins have been identified and characterized, but little is known about the identities of the sugars present on the spore surface. It is, however, known that their presence on the spore surface modulates the relative hydrophobicity of the spore (7–9).

Coat formation is finely controlled by a variety of mechanisms acting at various levels. The synthesis of coat proteins is regulated by at least two mother cell-specific sigma subunits of RNA polymerase and at least three additional transcriptional regulators. These transcription factors act in a temporal sequence, controlling the expression of the coat structural genes (cot genes) in the mother cell (6). At least some coat proteins are subject to posttranslational maturation events, including proteolytic cleavage, cross-linking, phosphorylation, and glycosylation reactions (10). An important subset of coat proteins, referred to as morphogenetic proteins, controls the assembly of other coat components and the formation of coat and crust layers (11–15). The subset of morphogenetic coat proteins includes major members such as SpoIVA, SafA, SpoVID, and CotE, which are needed to drive coat and crust formation, and minor members responsible for the maturation or assembly of some other coat proteins (6, 10).

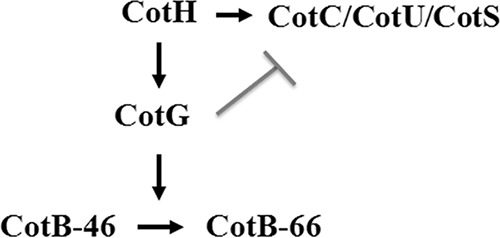

CotG belongs to the second group of morphogenetic proteins. It was initially characterized as an abundant component of the outer coat layer (16) needed, together with CotH, for the maturation of another outer coat protein, CotB (16, 17). CotG is a 195-amino-acid protein characterized by a central region of 126 residues formed by positively charged and randomly coiled tandem repeats. It has been proposed that the repeats are the outcome of multiple rounds of gene elongation events in an ancestral minigene (18). CotG is not widely conserved in spore formers, and its homologues can be found in only two Bacillus and two Geobacillus species (10, 18). The structural gene coding for CotG is also unusual in that it is entirely contained between the promoter and the coding part of another gene, cotH, also coding for a morphogenetic coat protein (18, 19). More recently, CotG was identified as the target of extensive phosphorylation by a still unidentified enzyme (20). In that same study, it was also observed that CotG has a negative effect on the assembly of at least three coat proteins: CotC, CotU, and CotS (20). This negative effect is counteracted by CotH, and strains lacking both CotG and CotH assemble CotC, CotU, and CotS like the isogenic wild-type strain. When CotH is absent, CotG plays its negative role, and CotC, CotU, and CotS are not assembled (20). A model showing the interactions among these Cot proteins is presented in Fig. 1.

FIG 1.

Model of the CotH-dependent protein interaction network. Shown is a working model of the interactions among the indicated proteins. CotH has a positive effect on the assembly of CotG, CotC, CotU, and CotS (arrows). CotG in turn controls CotB maturation from the immature 46-kDa CotB form to the mature 66-kDa CotB form. The gray line indicates the negative effect of CotG on CotC, CotU, and CotS assembly (17, 20, 30).

In the present work, we have analyzed the genomes of the entirely sequenced Bacillus species and observed that, in most cases, they encode a CotG-like protein. These proteins do not have a conserved amino acid sequence with respect to CotG of B. subtilis, but they all share the same structural properties, and at least some of them share the unusual chromosomal organization of the cotG-cotH locus.

To gain insight into the role of such modular structures, we constructed and analyzed a series of deletion mutants expressing discrete modules of B. subtilis CotG, providing the first functional analysis of this novel class of modular morphogenetic proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bioinformatic analysis.

Orthologues of CotH were identified by a BLAST analysis (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) using the CotH sequence of Bacillus subtilis strain 168 (GenBank accession number NP_391487.1) as a query against Bacillales (taxonomic ID 1385). Completely sequenced Bacillus species containing a CotH orthologue (sharing a minimum of 40% identity with respect to the query sequence) were considered for analysis of the gene upstream of cotH. A list of species with completely sequenced genomes is available in the KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/catalog/org_list.html) and was used for genomic analysis.

Bacterial strains and transformation.

B. subtilis PY79 was used as the recipient strain for transformation procedures. Plasmid amplification for nucleotide sequencing, subcloning experiments, and transformation of Escherichia coli competent cells was performed with Escherichia coli strain DH5α (21). Transformation was performed by using previously described procedures: CaCl2-mediated transformation of E. coli (20) and two-step transformation of B. subtilis competent cells (22).

Genetic and molecular procedures.

Isolation of plasmids, restriction digestion, and ligation of DNA were carried out by using standard methods (21). Chromosomal DNA from B. subtilis was isolated as described previously (22).

Construction of a cotG internal deletion mutant.

DNA coding for the internal repeats of cotG was deleted by using the gene splicing by overlap extension (gene SOEing) technique (23). Briefly, two partially overlapping DNA fragments were obtained with oligonucleotide couples H19/Gsoe1 (to amplify the promoter and 5′ coding part of cotG) and X2/Gsoe2 (to amplify the 3′ coding region of cotG and its transcription terminator). The obtained PCR products were separately used as the templates for a linear PCR of 7 cycles using only the respective external primers H19 and X2, thus obtaining single-stranded fragments partially overlapping at their 3′ regions. The single-stranded products were mixed and used to perform a standard PCR program of 20 cycles, which led to their fusion. The recombinant fragment was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and sequenced to confirm the correct gene fusion. The modified version of cotG (here called cotGΔ) was then moved by BamHI-EcoRI digestion into the pDG1731 integrative vector commonly used to integrate cloned genes at the thrC locus of the B. subtilis chromosome. The resultant plasmid, pVS11, was linearized with ScaI and used to transform AZ603 (ΔcotG ΔcotH) (20) competent cells to generate strain AZ612, which carried a double-crossover recombination event at the nonessential thrC gene on the B. subtilis chromosome and carried the cotGΔ allele in a cotH background. Chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis AZ612 (ΔcotG ΔcotH thrC::cotGΔ) was used to transform competent cells of the AZ604 mutant (ΔcotG ΔcotH amyE::cotGstop-cotH), thus generating strain AZ613 expressing the deleted cotGΔ gene in the presence of wild-type cotH (ΔcotG ΔcotH amyE::cotGstop cotH thrC::cotGΔ).

To construct the cotG-Nterm and cotG-Cterm genes expressing only the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of CotG, respectively, the same gene SOEing procedure was used. Oligonucleotide couples H19/Gsoe3 and X2/Gsoe4 were used to amplify the 5′ region of cotG (promoter plus the N-terminal coding sequence) and the transcription terminator, and oligonucleotide couples H19/Gsoe5 and X2/Gsoe6 were used to amplify the cotG promoter and the 3′ region of cotG (C-terminal coding region plus the terminator). By using the same procedure as the one described above, we obtained recombinant genes expressing the N-terminal or the C-terminal region of CotG by PCR. The genes were subcloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector, confirmed by DNA sequencing, and then cloned into the BamHI/EcoRI sites of pDG1731, yielding plasmids pVS13 (containing cotG-Nterm) and pVS12 (containing cotG-Cterm). Both plasmids were separately used to transform competent cells of B. subtilis strain AZ603 (ΔcotG ΔcotH). The double-crossover recombination event at the thrC locus originated from strains AZ616 (ΔcotG ΔcotH thrC::cotG-Nterm) and AZ614 (ΔcotG ΔcotH thrC::cotG-Cterm), expressing the CotG-Nterm and CotG-Cterm forms, respectively, in a cotH background. Chromosomal DNA of these strains was used to transform competent cells of AZ604 to obtain AZ617 (ΔcotG ΔcotH amyE::cotGstop cotH thrC::cotG-Nterm) and AZ615 (ΔcotG ΔcotH amyE::cotGstop cotH thrC::cotG-Cterm), expressing the CotG-Nterm and CotG-Cterm forms, respectively, in the presence of cotH.

Construction of strains expressing the cotS::gfp fusion.

Chromosomal DNA of strain AZ644 (cotS::gfp) (19) was used to transfer the cotS-gfp fusion into strains AZ612 (ΔcotG ΔcotH thrC::cotGΔ), AZ614 (ΔcotG ΔcotH thrC::cotG-Cterm), and AZ616 (ΔcotG ΔcotH thrC::cotG-Nterm), yielding AZ649, AZ660, and AZ661, respectively.

Transcriptional analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 14580 and Bacillus cereus ATCC 10987 5 h after the onset of sporulation by using an RNeasy Plus minikit (Qiagen, Milan, Italy) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNAs were dissolved in 50 μl of RNase-free water and stored at −80°C. The final concentration and quality of the RNA samples were estimated either spectrophotometrically or by agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining. Total RNAs were treated with RNase-free DNase (1 U/μg of total RNA) (Turbo DNA-free; Ambion) for 30 min at 37°C, and the reaction was stopped with DNase inactivation reagent.

For reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis, samples containing 2 μg of DNase-treated RNAs of B. licheniformis and B. cereus were incubated with oligonucleotide H1 (H1-lich and H1-cereus, respectively) at 65°C for 5 min and slowly cooled to room temperature (RT) to allow primer annealing. RNAs were then retrotranscribed by incubating the mixture at 50°C for 1 h in the presence of 1 μl AffinityScript multitemperature reverse transcriptase (Stratagene), 4 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 1× reaction buffer (Stratagene), and 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The enzyme was then inactivated at 70°C for 15 min. The cDNA was PCR amplified with oligonucleotide H1 (H1-lich or H1-cereus) coupled with H2 (H2-lich or H2-cereus), annealing in the cotH coding region, and H3 (H3-lich or H3-cereus), annealing in the cotH 5′ region, at the end of the divergent gene. As a control, PCRs were carried out with RNA not subjected to reverse transcription to exclude the possibility that the amplification products were derived from contaminating genomic DNA.

Spore purification, extraction of spore coat proteins, and Western blot analysis.

Sporulation was induced by exhaustion by growing cells in DSM (Difco sporulation medium) as described previously (22). After 30 h of incubation at 37°C, spores were collected, washed four times, and incubated overnight in H2O at 4°C to lyse residual sporangial cells, as described previously by Nicholson and Setlow (24). Spore coat proteins were extracted from a suspension of spores by SDS-DTT (22) or NaOH (24) treatment as described previously. The concentration of extracted proteins was determined by using a Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad), and 20 μg of total spore coat proteins was fractionated on 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The proteins were then electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose filter (Bio-Rad) for Western blot analysis according to standard procedures. CotC- and CotB-specific antibodies were used at working dilutions of 1:7,000. The horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody was used (Santa Cruz) as a secondary antibody. Western blot filters were visualized by using the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence (Pierce) method as specified by the manufacturer.

Fluorescence microscopy.

CotS assembly was monitored by fluorescence microscopy using an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) filter. Samples expressing the cotS::gfp fusion and containing both sporangia and mature spores were obtained after overnight incubation in DSM in order to induce sporulation. Exposure times were 588 ms, and the images were captured by using an Olympus DP70 digital camera.

Germination efficiency.

Purified spores were heat activated (20 min at 70°C) and diluted in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer containing 1 mM glucose, 1 mM fructose, and 10 mM KCl (GFK). After 15 min at 37°C, germination was induced by adding 10 mM asparagine to the mixture, and the optical density at 600 nm was measured at 5-min intervals for 60 min (22).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The CotG-like protein family.

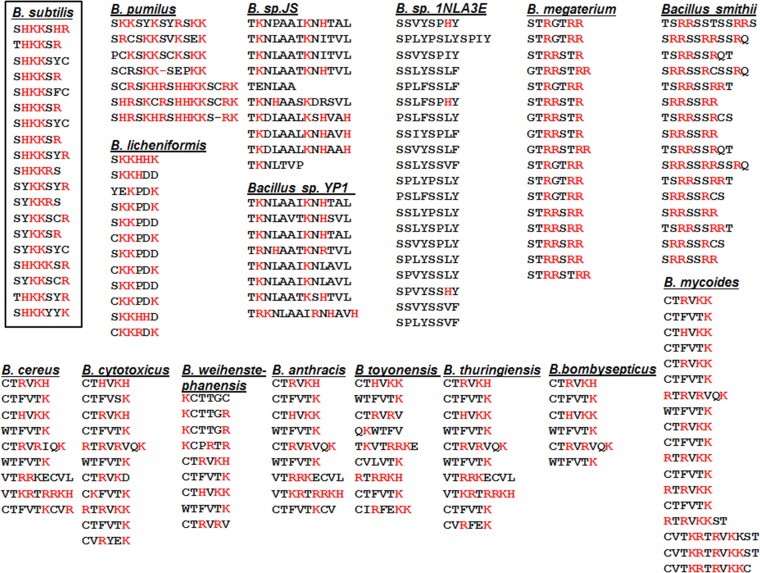

In B. subtilis, the cotG and cotH genes are adjacent on the chromosome and divergently transcribed and encode two spore coat proteins: CotH, conserved in several Bacillus and Clostridium species, and CotG, found in only three Bacillus and two Geobacillus species (10, 18). In all three CotG-containing bacilli, B. subtilis, B. amyloliquefaciens, and B. atrophaeus, the chromosomal organization of the cotG-cotH locus is conserved, with the two genes being adjacent and divergent and with cotG being entirely contained between the promoter and the coding region of cotH (18). We have now expanded and updated the analysis of the cotH-cotG locus in the chromosomes of all completely sequenced Bacillus genomes listed in the KEGG database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/catalog/org_list.html), selecting one representative strain for each species. We observed that 24 out of 35 entirely sequenced Bacillus species contain a CotH orthologue. Only 7 of the CotH-containing species also contain a CotG orthologue, and in all cases, cotG is adjacent and divergently transcribed with respect to cotH (see strains 1 to 7 in Table S1 in the supplemental material). The analysis of the 17 other CotH-containing species indicated that 15 of them have an open reading frame (ORF) adjacent and divergent with respect to cotH (see strains 8 to 22 in Table S1 in the supplemental material). The product of the divergent ORF is known to code for exosporium protein B (ExsB) in B. anthracis (25), while in all other species, it codes for a protein of unknown function. Although not homologous to CotG, these proteins share some peculiar structural features with CotG. The most striking of these features is the presence of a central region consisting of several repeats (Fig. 2). In various species, the numbers and amino acid sequences of such repeats are highly variable (Fig. 2). However, all these putative proteins share a list of common traits, as summarized in Table 1: (i) a high isoelectric point (pI), ranging from 9.28 for B. anthracis to 12.95 for B. megaterium; (ii) an elevated percentage of positively charged amino acids, ranging from 22.5% for Bacillus sp. JS to 44.6% for B. pumilus; and (iii) an elevated percentage of serine and threonine residues, ranging from 9.1% for B. licheniformis to 39% for B. megaterium. The only exception is the sequence found in Bacillus sp. 1NLA3E, which has a low percentage of positively charged amino acids and, as a consequence, a low pI. Our bioinformatic analysis also predicted that these putative proteins contain many potential phosphorylation sites (Table 1) and that most of them have an unfoldability index of <0 and an instability index of >40 (Table 1). These two parameters are indicative of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), characterized by a nonordered, three-dimensional structure that can adopt a fixed structure after binding to a ligand or to another protein (26).

FIG 2.

Repeats of CotG and CotG-like proteins. The tandem repeats of CotG of B. subtilis (18) and of CotG-like proteins found in the indicated species are shown. B. subtilis CotG modules are boxed. Positively charged amino acids are in red.

TABLE 1.

Features of CotG-like proteins in Bacillus spp.

| Species (strain, protein identification)d | No. of residues | pI | % positively charged residues | % Ser-Thr residues | No. (%) of phosphorylated Thr or Ser residuesa | Unfoldability indexb | Instability indexc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis (168, BSU36070) | 195 | 10.26 | 47.2 | 21.0 | 28 (68) | −0.716 | 77.91 |

| B. anthracis (Sterne, BAS1898) | 186 | 9.28 | 29.6 | 13.4 | 8 (33) | −0.174 | 62.30 |

| B. cereus (ATCC 10987, BCE_2114) | 180 | 9.40 | 27.8 | 14.4 | 6 (26) | −0.167 | 58.53 |

| B. cytotoxicus (NVH39198, Bcer98_1534) | 182 | 9.73 | 35.1 | 12.6 | 9 (39) | −0.351 | 44.37 |

| B. licheniformis (ATCC 14580, BL01346) | 168 | 9.62 | 39.8 | 9.1 | 2 (13) | −0.536 | 26.21 |

| B. megaterium (QM B1551, BMQ_1411) | 195 | 12.95 | 43.0 | 39.0 | 50 (66) | −0.829 | 201.18 |

| B. pumilus (SAFR032, ND) | 216 | 10.95 | 44.5 | 21.0 | 40 (83) | −0.760 | 90.75 |

| B. thuringiensis (BMB171, BMB171_C1814) | 186 | 9.33 | 29.6 | 13.9 | 11 (42) | −0.175 | 61.96 |

| B. weihenstephanensis (KBAB4, BcerKBAB4_1895) | 196 | 9.62 | 31.9 | 15.1 | 8 (27) | −0.218 | 58.65 |

| B. mycoides (219298, DJ92_4596) | 233 | 10.22 | 35.6 | 20,2 | 24 (51) | −0.288 | 56.40 |

| B toyonensis (ND, Btoyo_4601) | 193 | 9.59 | 32.1 | 16.06 | 10 (32) | −0.225 | 65.58 |

| Bacillus sp. JS (ND, MY9_3666) | 154 | 10.66 | 22.5 | 18.8 | 7 (24) | +0.024 | 14.92 |

| Bacillus sp. 1NLA3E (ND, B1NLA3E_12550) | 220 | 6.36 | 1.8 | 35.4 | 1 (1) | +0.340 | 86.25 |

| B. smithii (ND, BSM4216_1708) | 220 | 12.43 | 34.1 | 35.9 | 65 (76) | −0.613 | 183.13 |

| B. bombysepticus (ND, CY96_09240) | 192 | 9.64 | 31.2 | 15.1 | 10 (34) | −0.208 | 63.86 |

| Bacillus sp. strain YP1 (ND, QF06_16450) | 159 | 12.16 | 22.6 | 20.1 | 6 (18) | −0.002 | 5.79 |

Phosphorylation prediction was done by using the NetPhosBac 1.0 server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetPhosBac-1.0/). For each Ser and Thr residue, a score between 0 and 1 was calculated. When the score is ≥0.5, the residue is predicted to be a phosphorylation site.

Disorder prediction was done by using Foldindex (http://bip.weizmann.ac.il/fldbin/findex). Positive values indicate a structured polypeptide, whereas negative values indicate a disordered protein.

The instability index was determined by using ProtParam (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/). Values of ≥40 predict that the protein is unstable.

Protein identification is the protein code in the KEGG database. ND, not determined (the strain name is not available in the KEGG list or the protein is not available [the divergent ORF upstream of cotH is not annotated in the NCBI database]).

Although these proteins have different amino acid sequences and therefore do not share significant homologies with CotG of B. subtilis or among themselves, based on their chromosomal location and their structural features, we refer to them here as CotG-like proteins.

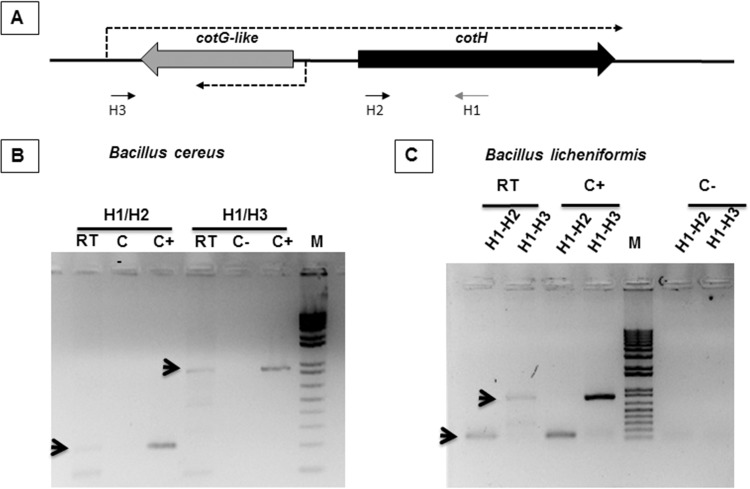

In B. subtilis and in two CotG-containing Bacillus species analyzed previously (18), cotG is entirely contained between the promoter and the coding region of cotH. An RT-PCR approach was used to verify whether the same situation also occurred in two of the other strains considered in this study and available at the BGSC (Bacillus Genetic Stock Center), B. cereus ATCC 10987 and B. licheniformis ATCC 14580. Total RNA was extracted from sporulating cells of both species 5 h after the beginning of sporulation and used as a template to produce a specific cDNA with synthetic oligonucleotide H1 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), mapping in the cotH coding region (Fig. 3A). The cDNA was then PCR amplified with oligonucleotide H1 coupled with H2 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), annealing in the cotH coding region, and H3 (see Table S2), annealing in the cotH upstream region, at the end of the divergent gene (Fig. 3A). In both organisms, we observed an amplification product of the expected size (Fig. 3B and C) with both oligonucleotides pairs (H1/H2 and H1/H3), indicating that, as in B. subtilis, cotH is transcribed from a distal promoter and that the cotG-like gene is located between the cotH promoter and its coding region. The conservation of the unusual transcriptional organization also found in these two species supports the idea that these proteins of unknown function may have a role similar to that of B. subtilis CotG and may be considered a protein family typical of Bacillus species.

FIG 3.

cotH transcription in B. cereus and B. licheniformis. (A) Schematic representation of the cotH-cotG locus. Arrows indicate the positions of the synthetic oligonucleotides used for RT-PCR. Dashed arrows indicate the direction of transcription. (B and C) Reverse transcription reactions were performed by using total RNA from sporulating cells of B. cereus (B) or B. licheniformis (C) as a template and were primed with oligonucleotide H1. Amplification reactions were performed by using cDNA as the template and oligonucleotide pair H1/H2 or H1/H3, as indicated. Negative controls (C−) and positive controls (C+) were RNA samples treated and not treated with DNase, respectively. Arrows indicate the amplification products of the expected size, and M indicates the molecular weight marker.

Construction of cotG mutant alleles.

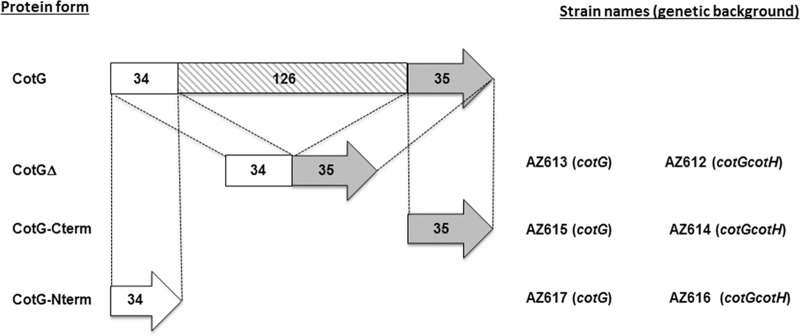

The presence of positively charged repeats in the central region of all CotG-like proteins and of C- and N-terminal regions prompted us to investigate the function of such modules. To address this question, we used B. subtilis to construct three cotG deletion mutants (Fig. 4) either lacking all central repeats (cotGΔ) or expressing only the N-terminal part (cotG-Nterm) or only the C-terminal region (cotG-Cterm) of CotG. Each mutant allele of cotG was independently integrated at the thrC locus on the B. subtilis chromosome of parental strain PY79 and then moved by chromosomal DNA-mediated transformation into strain AZ604 (ΔcotG-ΔcotH amyE::cotGstop cotH) not expressing the wild-type copy of cotG (20). It is known that CotG action is mediated by CotH when it exerts either its positive role on CotB maturation or its negative role on CotC, CotU, and CotS assembly and on spore germination (20). Therefore, by using chromosomal DNA-mediated transformation, we moved all mutant cotG alleles in strain AZ603 (ΔcotG-ΔcotH) also lacking the cotH gene (20). Strains in both mutant backgrounds are indicated in Fig. 4 and are described in Table S3 in the supplemental material.

FIG 4.

CotG versions. The wild-type protein (CotG) is represented as being composed of three domains: the N- and C-terminal regions of 34 and 35 amino acids, respectively, and a central domain of 126 amino acids organized into tandem repeats (18). CotGΔ lacks the central domain, and CotG-Cterm and CotG-Nterm contain only the C- and N-terminal domains, respectively. All constructs were integrated into the chromosomes of strains carrying either a null mutation in cotG or a double-null mutation in cotG and cotH (indicated in parentheses). The names of strains carrying the different cotG alleles in the two genetic backgrounds are shown.

Spores of all strains indicated in Fig. 4 were then analyzed to assess the role of the various CotG modules in the assembly of some CotG-controlled proteins and in spore germination.

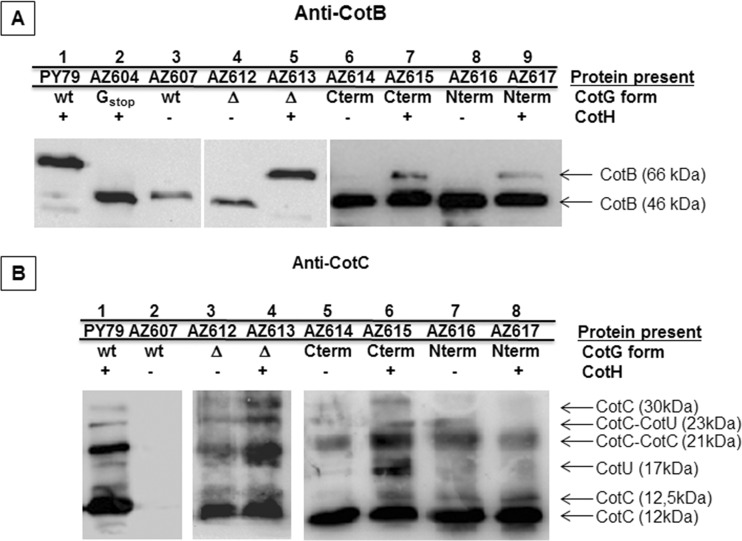

The C- and N-terminal modules of CotG are essential for CotB maturation.

CotB is extracted from wild-type spores in its 66-kDa mature form (17). CotB maturation from the 46-kDa form requires the presence of both CotH and CotG (17, 20). The Western blot shown in Fig. 5A confirms that without CotG (lane 2) or CotH (lane 3), only the immature CotB form is assembled onto the spore, showing that all three mutant versions of CotG allowed CotB maturation in a CotH-dependent way. Therefore, all three versions of CotG were able to cooperate with CotH and convert the 46-kDa CotB form (CotB-46) into CotB-66. However, CotGΔ was clearly more efficient than CotG-Cterm or CotG-Nterm and was able to convert all CotB-46 molecules into CotB-66 to the same extent as that found for the wild type (Fig. 5A). CotG-Cterm or CotG-Nterm was able to produce some CotB-66, but the major part of the CotB molecules were in the 46-kDa form (Fig. 5A). Based on this, we speculate that both the C- and N-terminal regions of CotG cooperate with CotH and act somehow synergistically when both are present. The results shown in Fig. 5A also suggest that the central repeats of CotG are not required for CotB maturation.

FIG 5.

Effects of CotG on CotB, CotC, and CotU assembly. Western blot analysis of coat proteins extracted from purified spores of the indicated strains was performed. Proteins were fractionated on 15% SDS-PAGE gels, electrotransferred onto a membrane, and incubated with anti-CotB (A) and anti-CotC (B) antibodies. The type of CotG allele expressed in each strain (CotG form) in the presence (+) or in the absence (−) of CotH is also indicated. wt, wild type.

The internal repeats are responsible for the negative effect of CotG on the assembly of CotC/CotU and CotS.

CotC and CotU share significant homologies and are both recognized by anti-CotC and anti-CotU antibodies (27, 28). They are assembled in several forms, including a CotC homodimer of 21 kDa and a CotC-CotU heterodimer of 23 kDa (29). It was recently reported (20) that CotH counteracts a not-understood negative role played by CotG on CotC and CotU assembly on the spore. In mutant strains lacking only CotG or both CotG and CotH, all CotC/CotU forms are normally present and assembled, but when CotG is present and CotH is not present, all forms of CotC and CotU are not found around the forming spore or in the mother cell cytoplasm (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 and 2) (20). As shown in Fig. 5B, none of the three mutant forms of CotG, CotGΔ, CotG-Cterm, and CotG-Nterm, had a negative effect on CotC or CotU, which were normally assembled around the forming spore, independently from the presence of CotH. This suggests that the internal repeats of CotG are directly involved in the negative role of CotG in CotC/CotU assembly.

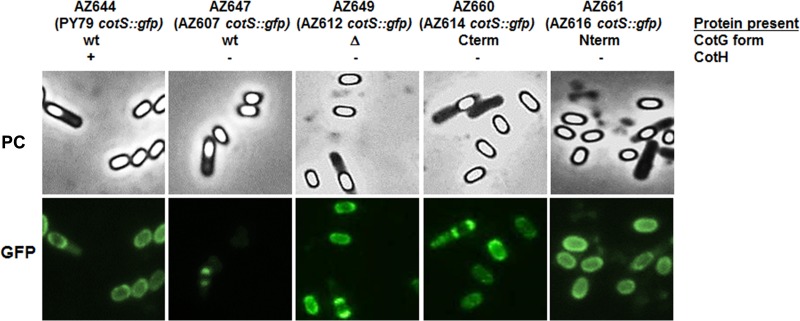

CotS is a 41-kDa protein whose assembly is negatively controlled by CotG when CotH is not present (20). A cotS::gfp fusion (19) was used to monitor the effects of CotG modules on CotS assembly. As shown in Fig. 6, only the wild-type version of CotG had a negative effect on CotS that was not assembled on mature spores. Instead, a normal CotS-dependent fluorescence signal was observed in mature spores as well as in sporulating cells of strains expressing each of the mutant CotG forms (CotGΔ, CotG-Cterm, and CotG-Nterm). As in the case of CotC/CotU, this suggests that the internal repeats of CotG are responsible for the negative role of CotG in CotS assembly.

FIG 6.

Effects of CotG on CotS assembly. A cotS::gfp fusion was introduced into a wild-type strain (PY79) and into cotH strains expressing wild-type CotG (AZ607), CotGΔ (AZ612), CotG-Cterm (AZ614), and CotG-Nterm (AZ616). Representative fields using phase-contrast microscopy (PC) and fluorescence microscopy (green fluorescent protein [GFP]) are shown. The exposure time was 588 ms in all cases.

Taken together, the results shown in Fig. 5 and 6 indicate that (i) the N-terminal and C-terminal modules of CotG are responsible for the positive effect of CotG on CotB maturation, acting synergistically, and (ii) the internal repeats of CotG are responsible for the negative effects of CotG on the assembly of CotC, CotU, and CotS.

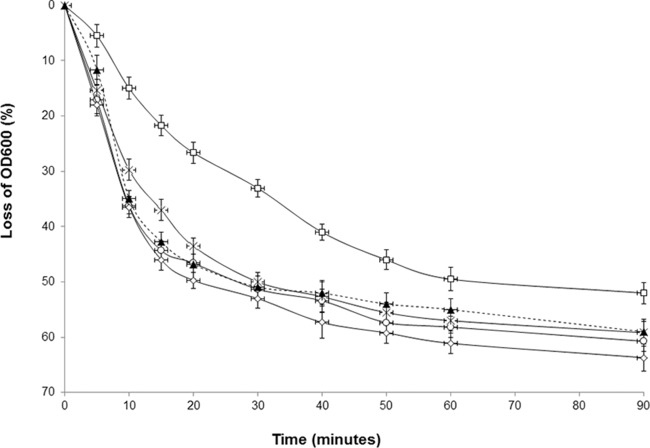

The internal repeats are responsible for the negative effect of CotG on the efficiency of germination.

It was previously reported that a cotH-null mutation causes a small defect in the efficiency of spore germination in response to asparagine (19). More recently, we showed that such a defect is actually due not to the lack of CotH but rather to the presence of CotG that, in the absence of CotH, exerts its negative effect (20). Indeed, mutant spores lacking only CotG or both CotG and CotH have a germination efficiency similar to that of an isogenic wild-type strain (20). To verify whether the internal repeats are also involved in this negative effect of CotG, we analyzed the germination efficiency of strains expressing the wild-type and mutant cotG alleles in a cotH background. As shown in Fig. 7, the only strain showing a defect in the efficiency of spore germination was the strain expressing the wild-type allele of cotG. The efficiency of germination of spores of all other strains was identical to that of wild-type spores (Fig. 7, dashed line). The results shown in Fig. 7 then indicate that the internal repeats of CotG are involved in the negative effect of this protein on spore germination.

FIG 7.

Effects of CotG on germination efficiency. Spores derived from strains expressing wild-type CotG (AZ607) (squares), CotGΔ (AZ612) (crosses), CotG-Cterm (AZ614) (circles), and CotG-Nterm (AZ616) (diamonds) in a cotH background were tested for germination efficiency and compared with those of a wild-type strain (PY79) (dashed line). Germination was induced by Asn-GFK and measured as the percent loss of the optical density at 600 nm. Error bars are based on the standard deviations of data from four independent experiments. OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

Conclusions.

CotG of B. subtilis is not highly conserved in the Bacillus genus; however, a CotG-like protein with a modular structure and chemical features similar to those of CotG is common in spore-forming bacilli, at least when cotH is also present. The conservation of CotG-like proteins in almost all species containing a CotH orthologue suggests that the two proteins act together and may have a relevant role in the structure and function of the Bacillus spore. To address the function of the various modules of CotG of B. subtilis, we have constructed mutants expressing CotG-deleted forms lacking the central modular region (CotGΔ) or expressing only the N- or the C-terminal part of CotG. Analysis of the various mutants allowed us to propose that the N- and C-terminal modules are able to both interact with CotH and mediate CotB maturation and that this interaction is synergistic. The central part of CotG, containing the repeats of positively charged amino acids, is not involved in CotB maturation but is instead responsible for the negative effect of CotG on the assembly of at least three coat components, CotC, CotU, and CotS, and on the efficiency of spore germination. CotH counteracts this negative effect, ensuring the correct assembly of the spore coat. Our findings indicate that CotG and CotH are functionally linked to each other and support the idea that the entire cotH-cotG locus and not only cotH has been conserved during the evolution of spore-forming bacilli.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Luciano Di Iorio for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00023-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Losick R, Youngman P, Piggot PJ. 1986. Genetics of endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet 20:625–669. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.003205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stragier P, Losick R. 1996. Molecular genetics of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet 30:297–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson WL, Munakata N, Horneck G, Melosh HJ, Setlow P. 2000. Resistance of Bacillus subtilis endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 64:548–572. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.3.548-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Setlow P. 2006. Spores of Bacillus subtilis: their resistance to and killing by radiation, heat and chemicals. J Appl Microbiol 101:514–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dworkin J, Shah IM. 2010. Exit from dormancy in microbial organisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:890–896. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKenney PT, Driks A, Eichenberger P. 2013. The Bacillus subtilis endospore: assembly and functions of the multilayered coat. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:33–44. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plata G, Fuhrer T, Hsiao TL, Sauer U, Viktup D. 2012. Global probabilistic annotation of metabolic networks enables enzyme discovery. Nat Chem Biol 8:848–854. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cangiano G, Sirec T, Panarella C, Isticato R, Baccigalupi L, De Felice M, Ricca E. 2014. The sps gene products affect the germination, hydrophobicity, and protein adsorption of Bacillus subtilis spores. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:7293–7302. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02893-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abe K, Kawano Y, Iwamoto K, Arai K, Maruyama Y, Eichenberger P, Sato T. 2014. Developmentally-regulated excision of the SPβ prophage reconstitutes a gene required for spore envelope maturation in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Genet 10:e1004636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henriques AO, Moran CP Jr. 2007. Structure, assembly and function of the spore surface layers. Annu Rev Microbiol 61:555–588. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPherson DC, Kim H, Hahn M, Wang R, Grabowski P, Eichenberger P, Driks A. 2005. Characterization of the Bacillus subtilis spore morphogenetic coat protein CotO. J Bacteriol 187:8278–8290. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.24.8278-8290.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa T, Isidro AL, Moran CP Jr, Henriques AO. 2006. Interaction between coat morphogenetic proteins SafA and SpoVID. J Bacteriol 188:7731–1741. doi: 10.1128/JB.00761-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim H, Hahn M, Grabowski P, McPherson D, Otte MM, Wang R, Ferguson CC, Eichenberger P, Driks A. 2006. The Bacillus subtilis spore coat protein interaction network. Mol Microbiol 59:487–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang KH, Isidro AL, Domingues L, Eskandarian HA, McKenney PT, Drew K, Grabowski P, Chua MH, Barry SN, Guan M, Bonneau R, Henriques AO, Eichenberger P. 2009. The coat morphogenetic protein SpoVID is necessary for spore encasement in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 74:634–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Francesco M, Jacobs JZ, Nunes F, Serrano M, McKenney PT, Chua MH, Henriques AO, Eichenberger P. 2012. Physical interaction between coat morphogenetic proteins SpoVID and CotE is necessary for spore encasement in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 194:4941–4950. doi: 10.1128/JB.00914-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sacco M, Ricca E, Losick R, Cutting S. 1995. An additional GerE-controlled gene encoding an abundant spore coat protein from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 177:372–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zilhao R, Serrano M, Isticato R, Ricca E, Moran CP Jr, Henriques AO. 2004. Interactions among CotB, CotG, and CotH during assembly of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. J Bacteriol 186:1110–1119. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.4.1110-1119.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giglio R, Fani R, Isticato R, De Felice M, Ricca E, Baccigalupi L. 2011. Organization and evolution of the cotG and cotH genes of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 193:6664–6673. doi: 10.1128/JB.06121-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naclerio G, Baccigalupi L, Zilhao R, De Felice M, Ricca E. 1996. Bacillus subtilis spore coat assembly requires cotH gene expression. J Bacteriol 178:4375–4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saggese A, Scamardella V, Sirec T, Cangiano G, Isticato R, Pane F, Amoresano A, Ricca E, Baccigalupi L. 2014. Antagonistic role of CotG and CotH on spore germination and coat formation in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS One 9:e104900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cutting S, Vander Horn PB. 1990. Genetic analysis, p 27–74. In Harwood C, Cutting S (ed), Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. 1989. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholson WL, Setlow P. 1990. Sporulation, germination and outgrowth, p 391–450. In Harwood C, Cutting S (ed), Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McPherson SA, Li M, Kearney JF, Turnbough CL Jr. 2010. ExsB, an unusually highly phosphorylated protein required for the stable attachment of the exosporium of Bacillus anthracis. Mol Microbiol 76:1527–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. 2005. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isticato R, Esposito G, Zilhão R, Nolasco S, Cangiano G, De Felice M, Henriques AO, Ricca E. 2004. Assembly of multiple CotC forms into the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. J Bacteriol 186:1129–1135. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.4.1129-1135.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isticato R, Pelosi A, Zilhão R, Baccigalupi L, Henriques AO, De Felice M, Ricca E. 2008. CotC-CotU heterodimerization during assembly of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. J Bacteriol 190:1267–1275. doi: 10.1128/JB.01425-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isticato R, Pelosi A, De Felice M, Ricca E. 2010. CotE binds to CotC and CotU and mediates their interaction during spore coat formation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 192:949–954. doi: 10.1128/JB.01408-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baccigalupi L, Castaldo G, Cangiano G, Isticato R, Marasco R, De Felice M, Ricca E. 2004. GerE-independent expression of cotH leads to CotC accumulation in the mother cell compartment during Bacillus subtilis sporulation. Microbiology 150:3441–3449. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.