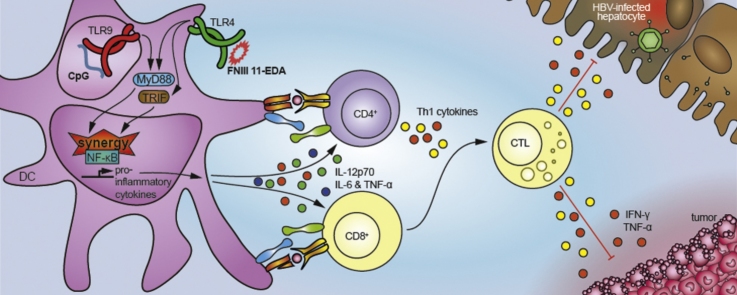

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Pattern recognition receptors, Toll-like receptors, Adjuvant, Adaptive immunity, Cancer vaccine, Hepatitis B virus, CpG, FNIII EDA

Highlights

-

•

FNIII 11-EDA and CpG synergize in vitro to enhance activation of dendritic cells.

-

•

Immunization with both adjuvants induces a potent antigen-specific Th1 response in vivo.

-

•

Co-adjuvanted OVA mediates regression of E.G7-OVA tumors through CTL response.

-

•

Co-adjuvanted HBsAg induces seroconversion and clearance of circulating virus in HBV-Tg mice.

Abstract

Subunit vaccines, employing purified protein antigens rather than intact pathogens, require the addition of adjuvants for enhanced immunogenicity with a correct balance between strong activation of the immune system and low toxicity. Here we show that the endogenous (i.e., autologous) non-toxic TLR4 agonist extra domain A type III repeat of fibronectin (FNIII EDA) can synergize with the exogenous (i.e., bacterial), toxic-at-high-dose, TLR9 agonist CpG to induce efficient cellular immune responses while keeping the dose of CpG low. The efficacy of the combined TLR agonists, even at half-doses, led to stronger dendritic cell activation, enhanced cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation as well as stronger humoral response, compared to the individual agonists given at full doses. Immune cells induced after vaccination with the co-adjuvanted formulation could mediate tumor regression in an E.G7-OVA tumor model, and eradicate circulating hepatitis B virus (HBV) in a transgenic HBV model. Together, these results show that endogenous TLR agonists, such as variants of FNIII EDA, can synergize with exogenous TLR ligands, such as CpG, and strongly enhance cellular immune responses, while improving their safety profile.

1. Introduction

The benefits of synthetic adjuvants toward improved vaccination safety and efficacy are indisputable, however the perfect balance between activation of the immune system and side effects remains somewhat elusive. A possible strategy to achieve this desired balance would be the optimization of Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonist-based adjuvants [1]. The TLR9 agonist unmethylated CpG oligodeoxynucleotide induces the maturation of dendritic cells (DCs), leading to a potent B cell humoral response as well as the secretion of Th1-biasing cytokines [2]. Although safe at low doses [2], [3], increasing the amount of CpG when the targeted disease requires a stronger response has been associated with risks of toxicity [4]. The endogenous (i.e., autologous, derived from the mammal itself) TLR4 agonist alternatively spliced type III repeat extra domain A of fibronectin (FNIII EDA) [5] and its variant FNIII 11-EDA have showed their ability to induce functional CD8+ T cell responses without toxicity [6], [7], [8].

Although single TLR targeting strategies have shown promising results, some combinations of TLR-agonists are known to synergize [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. The strength, and most importantly the quality, of the T cell response induced by specific combinations of TLR agonists can be enhanced [13]. This signaling crosstalk can be predicted looking at the activation through MyD88 along with another MyD88-independent signaling such as TRIF [10]. The MyD88 pathway can be activated by most TLR ligands while the TRIF pathway can be activated only by TLR3 and 4. We thus hypothesized that a combined administration of FNIII 11-EDA and CpG could synergize, thus activating immune cells more efficiently than either alone, allowing a reduction of the total dose of each adjuvant needed and lowering inherent toxicity.

When tested in vitro, combination of FNIII 11-EDA and CpG led to synergistic activation of dendritic cells (DCs), as measured by the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Synergy was also observed in vivo, where intradermal administration of the co-adjuvanted vaccine led to a potent Th1 immune response through activation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as an increase in antibody production. When delivered as a therapeutic vaccine in an E.G7-OVA tumor model, functional cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) generated by the co-adjuvanted vaccine induced tumor regression and led to an enhanced mouse survival. Finally, we sought to explore the ability of this TLR-agonist combination to break immune tolerance in a chronic hepatitis B transgenic mouse model (HBV-Tg) [14], [15]. Immunization of HBV-Tg mice with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) adjuvanted with a combination of CpG and FNIII 11-EDA induced a potent antiviral immune response, as observed by the clearance of HBsAg from the circulation and concomitant development of anti-HBsAg antibodies.

Together, these results show that CpG and FNIII 11-EDA synergize toward an enhanced activation of the immune system in an antigen-specific manner, inducing tumor regression and increasing HBV seroconversion in therapeutic vaccine settings, while minimizing the dose of potentially toxic adjuvant.

2. Methods

2.1. Reagents and recombinant proteins

Low endotoxin grade OVA (<0.01 EU/μg protein) was used for immunization (Hyglos). CpG type-B 1826 oligonucleotide (5′-TCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT-3′) was purchased from Microsynth AG and HBsAg from Prospec-Tany TechnoGene Ltd. FNIII 11-EDA was produced and purified as described by Julier et al. [6].

2.2. Mice

C57BL/6J mice (aged 7–8 weeks) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (France). Chi 1.3.32 (line 1.3.32, on a C57BL/6J background, aged 7–10 weeks) mice replicating HBV at high levels in the liver and kidneys, were kindly provided by Dr. Didier Trono (EPFL) [14]. Mice were kept under pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility of EPFL. All experiments were performed in accordance with Swiss law and with approval from the Cantonal Veterinary Office of Canton de Vaud, Switzerland.

2.3. In vitro stimulation of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs)

Murine BMDCs were generated as described elsewhere [16]. On day 8, 5 × 105 cells/well were plated on 96-well plates in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (PS), and incubated for 6 h with 0, 0.5, 1 or 2 μM of CpG and/or recombinant FNIII 11-EDA. To block interactions with any potentially contaminating LPS, FNIII 11-EDA was pre-incubated with 10 μg/ml of polymixin B. Cytokines released in the supernatant were measured by ELISA (eBioscience).

2.4. Stimulation of antigen-specific response

C57BL/6J mice were immunized by intradermal injection in the four footpads with a total dose of 50 μg OVA adjuvanted with 40 μg of CpG (referred to as full-dose CpG) or 5 nmol (105 μg) of FNIII 11-EDA (referred to as full-dose FNIII 11-EDA) or 20 μg of CpG and 2.5 nmol (52.5 μg) of FNIII 11-EDA (referred to as half doses) combined on day 0 and day 14. On day 19 mice were sacrificed, and spleen, blood and/or liver were harvested for ex vivo restimulation and flow cytometry staining.

2.5. Ex vivo antigen-specific cell restimulation

Liver immune cells were isolated from hepatocytes by low speed spins, and debris were removed using a 37.5% Percoll® (GE Healthcare) gradient. Blood, splenocytes, and liver cells were exposed for 5 min at r.t. to 0.155 M NH4Cl to lyse erythrocytes. For 6 h restimulation, immune cells were cultured ex vivo at 37 °C for 6 h in the presence of 40 μg/mL of HBsAg or 100 μg/mL of OVA in full media. After 3 h, Brefeldin-A (5 μg/mL) was added and intracellular cytokine production was assessed by flow cytometry. Restimulation was also carried out over 3 days for measurement of secreted cytokines by ELISA.

2.6. Tumor growth assays

106 E.G7-OVA tumor cells in 30 μL PBS (Invitrogen) were implanted s.c. in the back at the level of the junction between the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae of C57BL/6J mice. Mice were treated when their tumor reached 50 ± 5 mm3 and received a second injection of the same treatment 6 days later. For this, mice were immunized by injection in the four footpads with a total dose of 50 μg OVA adjuvanted with 40 μg of CpG (referred to as full-dose CpG) or 5 nmol (105 μg) of FNIII 11-EDA (referred to as full-dose FNIII 11-EDA) or 20 μg of CpG and 2.5 nmol (52.5 μg) of FNIII 11-EDA or 20 μg of CpG alone without FNIII 11-EDA. Tumors were measured 5 times per week and volumes were calculated as ellipsoids based on three orthogonal measures. Animal were killed when the tumor reached 1000 mm3 or for humane reasons such as tumor necrosis, excessive loss of weight or evident isolation from the other animals in accordance with Swiss regulations.

2.7. Hepatitis B study

All experiments carried out with HBV-Tg mice were performed in P2 and P3 biosafety levels. HBV-Tg mice were immunized by intradermal injections in the four footpads with 10 μg HBsAg adjuvanted with 80 μg of CpG (referred to as full-dose CpG) or 10 nmol (210 μg) of FNIII 11-EDA (referred as full-dose CpG) or 40 μg of CpG and 5 nmol (105 μg) of FNIII 11-EDA (referred to as half-dose). Here the dose of each adjuvant was doubled compared to tumor experiment, as preliminary experiments with this model showed that relatively high doses were required. Mice were immunized twice, on days 0 and 14. Mice were sacrificed on day 19 and liver and spleen collected for ex vivo restimulation and flow cytometric analysis. Blood was collected for ELISA analysis.

2.8. Flow cytometry and ELISA

Viable cells were detected by LIVE/DEAD (L/D) Fixable Aqua stain (Invitrogen) and the following antibodies were used for surface and intracellular staining: CD3ɛ Pacific Blue, CD4 FITC, CD8 APC-Cy7, IFN-γ APC, LAMP1 PE, TNF-α PE (eBioscience), PE-labeled H-2Kb/SIINFEKL pentamer (ProImmune). The following steps were performed on ice. Cells were washed with PBS, stained for 15 min with Aqua L/D stain, resuspended in PBS with 2% FBS for surface staining for 15 min and fixed for 15 min in PBS + 2% PFA. IFN-γ intracellular staining was performed in PBS + 2% FBS supplemented with 0.5% saponin. Flow cytometry was performed using a CyAn ADP Analyzer (Beckman Coulter). Detection of HBsAg and IFN-γ were performed using an HBsAg ELISA kit (AMS biotechnology) and a Ready-Set-Go ELISA Kit (eBioscience), respectively, according to the manufacturers protocol.

2.9. Data analysis

Flow cytometry data was analyzed using FlowJo (TreeStar Inc.). Graphing and statistical analyses – 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test – were performed using GraphPad Prism (***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. FNIII 11-EDA and CpG activate DCs in a synergistic manner

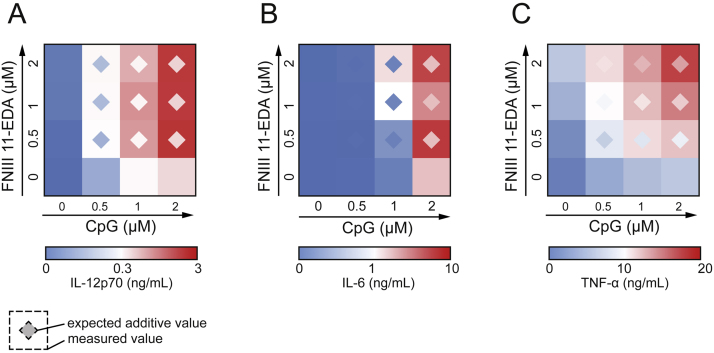

To determine whether FNIII 11-EDA and CpG were able to synergistically activate DCs, binomial combinations of both adjuvants were tested in vitro. Although FNIII 11-EDA or CpG alone induced only mild activation of DCs at the doses tested (up to 2 μM for each CpG and FNIII 11-EDA), their combination led to synergistic increases in the production of IL-12p70 (Fig. 1A, Fig. S1A), IL-6 (Fig. 1B, Fig. S1B), and TNF-α (Fig. 1C, Fig. S1C). Indeed, combination of both agonists resulted in more than twice the expected theoretical amount of cytokine secreted for most concentration combinations tested. Fig. S1 shows the actual measured concentrations of cytokines, from which the heat maps in Fig. 1 were calculated.

Fig. 1.

CpG and FNIII 11-EDA show synergistic activation of dendritic cells and stimulate strong IL-12p70, IL-6 and TNF-α production. Secretion of IL-12p70 (A), IL-6 (B) and TNF-α (C) by DCs in vitro after 6 h incubation with 0, 0.5, 1 or 2 μM of CpG and/or recombinant FNIII 11-EDA. Data show ELISA readouts of measured and expected cytokine concentrations as heat maps; color scales are indicated. Detailed values can be found in Fig. S1.

3.2. Co-immunization with FNIII 11-EDA and CpG induces potent Th1 response and increases cytotoxic activity of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in vivo

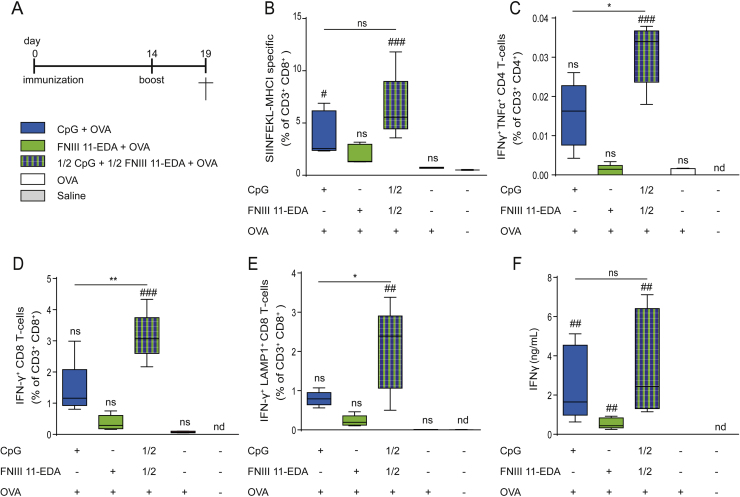

We next evaluated the ability of FNIII 11-EDA and CpG to synergize in vivo toward mounting a potent antigen-specific response in mice using OVA as model antigen. Both vaccinating with full-dose CpG or combination of both adjuvants at half-doses induced significantly higher levels of antigen-specific (SIINFEKL-MHCI-pentamers+) CD8+ T cells compared to full dose of FNIII 11-EDA that had no observable effect (Fig. 2B). Following ex vivo restimulation with OVA, combination of both adjuvants induced significantly higher frequency of IFN-γ+TNF-α+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2C), compared to the other formulations. Accordingly, the combination of adjuvants could induce a significant increase in IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2D) and degranulating LAMP1+ CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2E) compared to single adjuvants. However, the total amount of IFN-γ produced by splenocytes was not significantly enhanced compared to full dose of CpG, but was increased two folds compared to FNIII 11-EDA (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

FNIII 11-EDA and CpG are effective at inducing antigen-specific CD8+ T cell and Th1 responses in vivo. (A) Immunization schedule. C57BL/6J mice were immunized by intradermal injection in the four footpads with a total of 50 μg of OVA adjuvanted with 40 μg of CpG or 5 nmol (105 μg) of FNIII 11-EDA or 20 μg of CpG plus 2.5 nmol (52.5 μg) of FNIII 11-EDA on day 0 and 14. On day 19, mice were sacrificed, and the spleens were harvested. Data represent flow cytometry measurements of (B) frequency of SIINFEKL-MHC-I-specific+ CD8+ T cells in the spleen, (C) frequency of IFN-γ+TNF-α+ CD4+ splenocytes after 6 h ex vivo restimulation with OVA and (D, E) frequencies of IFN-γ+ and IFN-γ+LAMP1+ CD8+ splenocytes after 6 h ex vivo restimulation with SIINFEKL. (F) IFN-γ production from splenocytes restimulated for 3 days ex vivo with OVA, measured by ELISA. Box plots represent means ±95% confidence interval (n = 5). *,#P < 0.05; **,##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001; ns, not significant; nd, not detectable; #, ##, ###, comparison to naïve group.

3.3. Immunization with OVA adjuvanted with CpG plus FNIII 11-EDA mediates regression of E.G7-OVA tumors through functional cytotoxic T lymphocyte response

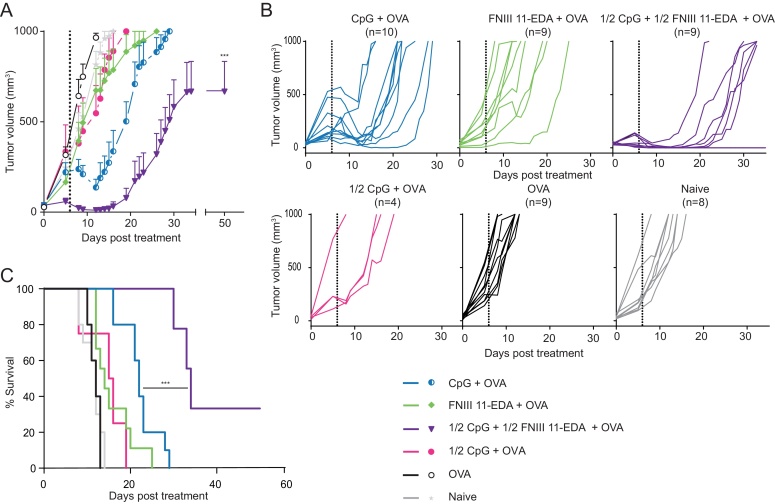

The level of functionality of CD8+ T cells generated after immunization with the antigen combined to CpG and FNIII 11-EDA was determined using the E.G7-OVA T cell lymphoma tumor model expressing OVA as a surrogate antigen. Enhanced tumor regression was observed both in response to OVA adjuvanted with full-dose CpG as well as half-doses of combined adjuvants as shown on average (Fig. 3A) and individual (Fig. 3B) tumor growth curves. Both groups temporarily showed strong tumor regression, although regression was enhanced when both adjuvants were co-administered. Tumor growth resumed faster when CpG was used alone, whereas in mice treated with combined adjuvants the treatment exerted control over tumor growth for a longer period of time (Fig. 3C). OVA alone or supplemented with full-dose FNIII 11-EDA had only a mild effect on tumor growth. In support of the synergistic effect of FNIII 11-EDA and CpG, vaccination with OVA with half-dose of CpG without FNIII 11-EDA also had only a mild effect on tumor growth.

Fig. 3.

Multiple injections of OVA adjuvanted with both CpG and FNIII 11-EDA mediate regression of E.G7-OVA tumors. C57BL/6J mice were injected s.c. with 106 E.G7-OVA cells on the back. Mice were then treated with OVA or OVA adjuvanted either with combined half doses of CpG and FNIII 11-EDA or with full doses of each adjuvant alone or with a half dose of CpG without FNIII 11-EDA when their tumor reached 50 ± 5 mm3 and received a second injection of the treatment 6 days later, represented on the figure by a dashed line. Mice were sacrificed when the tumor reached 1000 mm3 or for humane reasons. Data represent (A) average tumor volume, (B) individual growth curves for each mouse in the different groups and (C) survival curve. Growth curves represent mean ± SEM; Kaplan–Meier survival-curves (n = 4–10). ***P < 0.001, relative to CpG + OVA group.

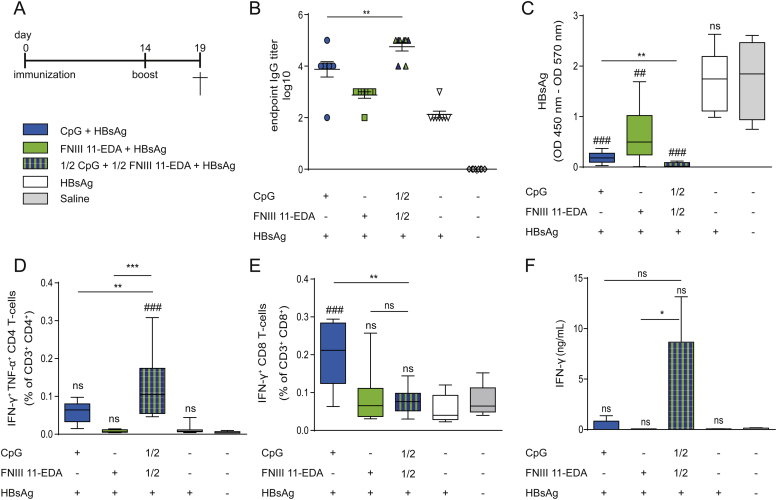

3.4. Immunization with HBsAg adjuvanted with CpG plus FNIII 11-EDA leads to strong Th1 cytokine secretion and limitation of circulating viruses

To explore the ability of the combination of CpG plus FNIII 11-EDA to induce a T cell response capable of breaking immune tolerance, the effect of the vaccine was assessed in HBV-Tg mice. Therapeutic vaccination with combination of both adjuvants and HBsAg led to a significant increase in production of anti-HBsAg IgGs (Fig. 4B) compared to all other groups. Vaccination with full-dose FNIII 11-EDA, full-dose CpG and combined half-doses of each adjuvants significantly affected and lowered levels of circulating HBsAg in blood (Fig. 4C). However, the combination of both adjuvants improved the elimination of the virally-produced protein compared to full-doses of each adjuvant alone. Furthermore, half-dose of CpG without the addition of FNIII 11-EDA was not sufficient to achieve significant reduction of the amount of circulating HBsAg (Fig. S2E), similarly to HBsAg only.

Fig. 4.

Co-injection of HBsAg adjuvanted with the two TLR agonists CpG and FNIII 11-EDA leads to enhanced production of inflammatory cytokines by T cells and anti-HBsAg seroconversion. (A) Immunization schedule. HBV-Tg mice were immunized by intradermal injection in the four footpads with 10 μg HBsAg adjuvanted with 80 μg of CpG or 10 nmol (210 μg) of FNIII 11-EDA or 40 μg of CpG and 5 nmol (105 μg) of FNIII 11-EDA on day 0 and day 14. On day 19 mice were sacrificed, and spleens, livers and blood were collected. (B) Anti-HBsAg IgGs levels in blood circulation and (C) concentration of HBsAg in the blood, as determined by ELISA. (D) Frequency of IFN-γ+TNF-α+ CD4+ T cells and (E) IFN-γ+TNF-α+ CD8+ T cells in the spleen after 6 h ex vivo restimulation with HBsAg, measured by flow cytometry. (F) Magnitude of IFN-γ production from splenocytes restimulated ex vivo for 3 days with HBsAg, evaluated by ELISA. Box plots represent means ±95% confidence interval (n = 8). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, not significant; ##, ###, comparison to naïve group.

Following ex vivo restimulation of splenocytes (Fig. 4D) or liver cells (Fig. S2B) with HBsAg, a significant increase in the frequency of Th1 cytokine-secreting CD4+ T cells was observed in response to co-vaccination with CpG and FNIII 11-EDA. While the frequency of CD8+ T cell secreting IFN-γ was higher when CpG was used as the only adjuvant (Fig. 4E), no difference in IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells populations in the liver was observed between the different treated groups (Fig. S2C). However, the total amount of IFN-γ produced ex vivo by restimulated splenocytes (Fig. 4F) and liver lymphocytes (Fig. S2D) was slightly increased by the combination of CpG and FNIII 11-EDA.

4. Discussion

In this study, we first assessed the ability of CpG and FNIII 11-EDA to activate DCs in a synergistic manner (Fig. 1, Fig. S1). Our results indeed show that activation of DCs was greatly enhanced in response to co-stimulation with both adjuvants compared to stimulation with each of them separately, as shown by the secretion of IL-12p70 (Fig. 1A, Fig. S1A), IL-6 (Fig. 1B, Fig. S1B) and TNF-α (Fig. 1C, Fig. S1C). These results are interesting, as TLR synergies have been reported to rely heavily on activation of the TRIF and MyD88 pathways [10]. Although FNIII EDA constructs induce the production of TNF-α [6], which expression is strictly MyD88-dependent [17], the ability of FNIII 11-EDA to synergize with a TLR9 ligand indicate that the TRIF pathway is also probably activated. This suggests that FNIII 11-EDA signals through both TRIF and MyD88 and would have the potential to synergize with most TLR ligand [12].

To determine whether CpG and FNIII 11-EDA would synergize in vivo and induce an enhanced antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response, we used OVA as a model antigen in a vaccination study. Interestingly, combination of half doses of CpG and FNIII 11-EDA was able to induce a comparable amount of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells to that obtained with a complete dose of CpG (Fig. 2B), while also leading to a higher quality response, as shown by the enhanced effector phenotype observed (Fig. 2C–E). Moreover it is especially remarkable that after ex vivo restimulation, the Th1-cytokine expression profile of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2C) induced by the combined half-doses was more than two-fold higher than the sum of the average frequency obtained with full doses of each adjuvant alone. A similar observation can be made on the average frequency of IFN-γ expressing-CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2D, E) although these differences were much attenuated when observing secretion of IFN-γ from the total splenocytes population after 3 days of restimulation (Fig. 2F). These results show that the in vitro observations of synergy between CpG and FNIII 11-EDA can be translated in vivo to induce a stronger or at least equivalent immune response while reducing the dose of CpG.

Both CpG and FNIII 11-EDA are known to induce efficient cellular immune responses capable of recognizing antigen-bearing targets [6], [18]. Using the E.G7-OVA T cell lymphoma model we assessed the ability of both adjuvants to synergize in inducing an effective anti-tumor CD8+ T cell response (Fig. 3). The half-dose of CpG without FNIII 11-EDA and full-dose FNIII 11-EDA used alone only slightly slowed tumor growth. Full dose CpG alone induced tumor regression, however growth resumed in all animals and none of them survived longer than 29 days. The majority of mice treated with both adjuvants together, however, lived longer than 33 days with one-third showing complete remission. It is also noteworthy that the tumors of more than half of the animals treated with both adjuvants temporarily regressed to undetectable levels before resuming growth, whereas only one out of ten tumors treated with CpG alone regressed to that level. It is possible that tumor escape in these animals was due to selective pressure leading to the appearance of OVA-free tumors cells [19]. In addition, it would be of interest to determine if increasing the number of injections would lead to complete remission of mice in the group treated with both adjuvants, as animals in these studies were treated only twice.

To demonstrate whether the cellular response induced by this synergy was sufficiently strong to overcome immune tolerance, we used HBV-Tg mice, which are tolerized toward HBsAg [14], [15]. In this model, the combination of CpG and FNIII 11-EDA enhanced the Th1 profile of the immune response both in the spleen and in the liver (Fig. 4E, Fig. S2B) compared to CpG alone. It also induced seroconversion, as shown by the presence of anti-HBsAg IgGs (Fig. 4B) in the blood. Together, these effects correlated with a significant reduction of circulating HBsAg proteins in the blood (Fig. 4C) in mice receiving both adjuvants. The lack of complete elimination of circulating HBsAg proteins can be explained by the fact that HBV is replicated from an integrated transgene in this model, which cannot be eliminated [15].

Recent studies have demonstrated that the use of a second antigen, namely hepatitis B core antigen led to stronger responses due to B cells participation [20]. This strategy could enhance our formulations. Moreover our lab has recently demonstrated that the conjugation of CpG to ultrasmall polymeric nanoparticles (NP) enhanced Th1 and cytotoxic T cell responses while maintaining a low dose of adjuvant. A synergy between NP-conjugated CpG and FNIII 11-EDA could further improve the safety profile of new vaccines [3], [21], [22]. Therapeutic vaccination in a disease such as hepatitis raises, however, questions of safety and especially of nonspecific T cell responses, which could potentially lead to liver damage in this example [23]. In our studies in the model utilized, we did not observe macroscopic effects of immune reactions toward the liver, and transgenic mice did not show any obvious signs of liver decompensation. This topic would, however, need further study to explore the extent to which the mounted immune response is indeed HBV-specific.

Together these results show that CpG and FNIII 11-EDA have the ability to synergize to break T cell tolerance and induce an enhanced antigen specific response. It is important that these improved effects were obtained while lowering the total dose of the foreign agent CpG, opening the door to the development of potent immunotherapies with fewer side effects and improved safety.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. S. Hirosue, Dr. P. Turelli, G. Diaceri, Y. Ben Saida, X. Quaglia, C. Racloz, S. Offner, P. Corthésy-Henrioud, M. Damo and F. Marzetta for technical assistance and discussions. Assistance from the Protein Production Core Facility and the Animal Facility staff of EPFL is gratefully acknowledged. This work was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Heinrich-Lohstöter-Stiftung and the European Research Council (NanoImmune).

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.057.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Dunne A., Marshall N.A., Mills K.H.G. TLR based therapeutics. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11(4):404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krieg A.M. CpG still rocks! Update on an accidental drug. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2012;22(2):77–89. doi: 10.1089/nat.2012.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Titta A., Ballester M., Julier Z., Nembrini C., Jeanbart L., van der Vlies A.J. Nanoparticle conjugation of CpG enhances adjuvancy for cellular immunity and memory recall at low dose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(December (49)):19902–19907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313152110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bode C., Zhao G., Steinhagen F., Kinjo T., Klinman D.M. CpG DNA as a vaccine adjuvant. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10(April (4)):499–511. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okamura Y., Watari M., Jerud E.S., Young D.W., Ishizaka S.T., Rose J. The extra domain A of fibronectin activates Toll-like receptor 4. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(13):10229–10233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Julier Z., Martino M.M., de Titta A., Jeanbart L., Hubbell J.A. The TLR4 agonist fibronectin extra domain A is cryptic, exposed by elastase-2; use in a fibrin matrix cancer vaccine. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8569. doi: 10.1038/srep08569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasarte J.J., Casares N., Gorraiz M., Hervas-Stubbs S., Arribillaga L., Mansilla C. The extra domain a from fibronectin targets antigens to TLR4-expressing cells and induces cytotoxic T cell responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;178(January (2)):748–756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mansilla C., Gorraiz M., Martinez M., Casares N., Arribillaga L., Rudilla F. Immunization against hepatitis C virus with a fusion protein containing the extra domain A from fibronectin and the hepatitis C virus NS3 protein. J Hepatol. 2009;51(September (3)):520–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu Q., Egelston C., Vivekanandhan A., Uematsu S., Akira S., Klinman D.M. Toll-like receptor ligands synergize through distinct dendritic cell pathways to induce T cell responses: implications for vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(42):16260–16265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805325105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagchi A., Herrup E.A., Warren H.S., Trigilio J., Shin H.-S., Valentine C. MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent pathways in synergy, priming, and tolerance between TLR agonists. J Immunol. 2007;178(2):1164–1171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Napolitani G., Rinaldi A., Bertoni F., Sallusto F., Lanzavecchia A. Selected Toll-like receptor agonist combinations synergistically trigger a T helper type 1-polarizing program in dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(August (8)):769–776. doi: 10.1038/ni1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Cordero J.L., Nembrini C., Stano A., Hubbell J.A., Maerkl S.J. A high-throughput nanoimmunoassay chip applied to large-scale vaccine adjuvant screening. Integr Biol (Camb) 2013;5(4):650–658. doi: 10.1039/c3ib20263a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu Q., Egelston C., Gagnon S., Sui Y., Belyakov I.M., Klinman D.M. Using 3 TLR ligands as a combination adjuvant induces qualitative changes in T cell responses needed for antiviral protection in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(2):607–616. doi: 10.1172/JCI39293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guidotti L.G., Matzke B., Schaller H., Chisari F.V. High-level hepatitis B virus replication in transgenic mice. J Virol. 1995;69(October (10)):6158–6169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6158-6169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dembek C., Protzer U. Mouse models for therapeutic vaccination against hepatitis B virus. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2015;204(February (1)):95–102. doi: 10.1007/s00430-014-0378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutz M.B., Kukutsch N., Ogilvie A.L.J., Rößner S., Koch F., Romani N. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol Methods. 1999;223:77–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin X., Kong J., Wu Q., Yang Y., Ji P. Effect of TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway on expression of IL-1β and TNF-α in synovial fibroblasts from temporomandibular joint exposed to lipopolysaccharide. Mediat Inflamm. 2015;2015(10):329405. doi: 10.1155/2015/329405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali O.A., Huebsch N., Cao L., Dranoff G., Mooney D.J. Infection-mimicking materials to program dendritic cells in situ. Nat Mater. 2009;8(March (2)):151–158. doi: 10.1038/nmat2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beaudette T.T., Bachelder E.M., Cohen J.A., Obermeyer A.C., Broaders K.E., Fréchet J.M.J. In vivo studies on the effect of co-encapsulation of CpG DNA and antigen in acid-degradable microparticle vaccines. Mol Pharm. 2010;6(4):1160–1169. doi: 10.1021/mp900038e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchmann P., Dembek C., Kuklick L., Jäger C., Tedjokusumo R., von Freyend M.J. A novel therapeutic hepatitis B vaccine induces cellular and humoral immune responses and breaks tolerance in hepatitis B virus (HBV) transgenic mice. Vaccine. 2013;31(8):1197–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeanbart L., Ballester M., de Titta A., Corthésy P., Romero P., Hubbell J.A. Enhancing efficacy of anticancer vaccines by targeted delivery to tumor-draining lymph nodes. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2(May (5)):436–447. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0019-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ballester M., Jeanbart L., de Titta A., Nembrini C., Marsland B.J., Hubbell J.A. Nanoparticle conjugation enhances the immunomodulatory effects of intranasally delivered CpG in house dust mite-allergic mice. Sci Rep. 2015;5(April):14274. doi: 10.1038/srep14274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batdelger D., Dandii D., Dahgwahdorj Y., Erdenetsogt E., Oyunbileg J., Tsend N. Clinical experience with therapeutic vaccines designed for patients with hepatitis. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(11):1159–1171. doi: 10.2174/138161209787846793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.