Abstract

Background: Estrogen exerts neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects in EAE and multiple sclerosis (MS), but its clinical application is hindered due to side effects and risk of tumor. Phytoestrogen structurally or functionally mimics estrogen with fewer side effects than endogenous estrogen. Icariin (ICA), an active component of Epimedium extracts, demonstrates estrogen-like neuroprotective effects. However, it is unclear whether ICA is effective in EAE and what are the underlying mechanisms. Objective: To determine the therapeutic effects of ICA in EAE and explore the possible mechanisms. Methods: C57BL/6 EAE mice were treated with Diethylstilbestrol, different dose of ICA and mid-dose ICA combined with ICI 182780. The clinical scores and serum Interleukin-17 (IL-17), Corticosterone (CORT) concentrations were then analyzed. Western blot were performed to investigate the expressions of glucocorticoid receptor (GR), estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and ERβ in the cerebral white matter of EAE mice. Results: High dose ICA is equally effective in ameliorating neurological signs of EAE as estrogen. Estrogen and ICA has no effects on serum concentrations of IL-17 in EAE. While the CORT levels were decreased by ICA at mid or high doses, the expressions of GR, ERα and ERβ were up-regulated by estrogen or different doses of ICA in a dosedependent manner. Estrogen induced the elevation of ERα more markedly than ICA. In contrast, ICA at mid and high doses promoted ERβ more significantly than estrogen. Conclusion: ICA exerts estrogen-like activity in ameliorating EAE via mediating ERβ, modulating HPA function and up-regulating the expression of GR in cerebral white matter. ICA may be a promising therapeutic option for MS.

Keywords: Icariin, estrogen, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal, estrogen receptor, glucocorticoid receptor

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system. Current therapies are effective in providing symptomatic relief, but do not stop the pathogenesis. Moreover, adverse effects of corticosteroid and immunosuppressant remain inevitable. It is therefore pivotal to develop novel therapy to suppress disease progression or relapse with fewer side effects.

Substantial evidence suggests that exogenous estrogen could be a potential therapeutic regimen. Mice treated with estrogen experienced significantly delayed onset and decreased severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) [1]. Imaging studies with MRI found that estrogen could reduce brain atrophy in patients with MS [2]. Estrogen was also shown to down-regulate the levels of cytokines TNF-α, IFN-γ, Interleukin-2 (IL-2) and up-regulate IL-4, IL-10 in EAE or MS patients [3,4]. Thus, basic and clinical studies support the neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory roles of estrogen in EAE and MS.

However, high dose or long term estrogen treatment may result in hypercoagulability, hypertension or edema, and increase the risk of tumor such as breast and endometrial cancer. Such side effects limit its clinical application. Researchers is therefore very interested in Phytoestrogen, a non-steroidal plant-derived xenoestrogen, which structurally or functionally mimics circulating estrogen. A number of studies have shown that phytoestrogens have beneficial effects in diverse disorders, including cancers [5,6], cardiovascular disease [7], Alzheimer’s disease [8] and osteoporosis [9], with fewer adverse complications than endogenous estrogen. The question now is whether phytoestrogen can substitute for estrogen in ameliorating EAE or MS?

Epimedii Herba, a genus of flowering plants in the family Berberidaceae, is a kind of phytoestrogen, which has been confirmed possessing strong estrogenic activity [10]. Icariin (ICA), a primary active component of Epimedium extracts, also has neuroprotective and estrogen-like effects and may have potential role in the treatment of age-related diseases, like neurodegeneration [11], memory and depressive disorders [12], chronic inflammation [13], diabetes [14], and osteoporosis [15]. However, there has been very limited data on MS or EAE. It is unclear whether ICA has therapeutic effects on EAE. The aims of our study were to investigate the effects of ICA on EAE and to explore the underlying mechanisms. Our results demonstrated that ICA ameliorates neurological signs, decreases serum Corticosterone (CORT) concentrations, up-regulates the expression of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in cerebral white matter, and exerts estrogen-like activity via mediating ERβ in EAE.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

C57BL/6 mice (female, 6-9 weeks old, weight 18 to 22 g) were purchased from Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center (License No. SCXK Yue 2012-0125). They had free access to food and water. All animal studies were performed in accordance with institutional animal ethics guidelines, and the protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Guangdong Pharmaceutical University.

EAE induction

EAE was induced according to the published protocol [16]. C57BL/6 female mice were immunized with an emulsion of MOG35-55 (Tocris Bioscience) in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by administration of pertussis toxin (PTX) (Enzo Life Sciences) in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), first on the day of immunization and then again the following day. Weight and neurological signs were evaluated daily. Neurological signs were scored per following criteria [17]: 0, no detectable signs of EAE; 0.5, limp distal tail; 1, complete limp tail; 1.5, limp tail and hind limb weakness; 2, unilateral partial hind limb paralysis; 2.5, bilateral partial hind limb paralysis; 3, complete bilateral hind limb paralysis; 3.5, complete hind limb paralysis and unilateral forelimb paralysis; 4, total paralysis of both forelimbs and hind limbs; 5, death.

Histological identification of EAE

The peak onset time of EAE was 12 days after immunization. Three mice were chosen randomly to be identified by pathological staining. Anesthetized mice were fixed by cardiac perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS over 15 min. Spinal cords were postfixed overnight at 4°C and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections were cut at 5 um and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) to assess inflammation, with solochrome cyanine staining for demyelination.

Experimental groups and treatment protocols

Forty-two EAE mice were divided randomly into six groups (A, B, C, D, E, and M). Six normal mice were fed under the same condition as group N. Study protocols are described in Table 1. ICA (Sigma-Aldrich), Diethylstilbestrol (Aladdin Industrial Corporation, Shanghai, China), and carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) (Sigma-Aldrich) were given by gavage, ICI 182780 (Sigma-Aldrich), an antagonist of ER, was injected subcutaneously. Treatment started at 12 days after inoculation when EAE mice developed severe clinical symptoms. Animals were given treatment once daily for five days.

Table 1.

Experimental groups and treatment protocols

| Group | n | Treatment | Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 7 | estrogen | 0.2 mg/kg/d, gavage |

| B | 7 | high-dose ICA | 300 mg/kg/d, gavage |

| C | 7 | mid-dose ICA | 150 mg/kg/d, gavage |

| D | 7 | low-dose ICA | 50 mg/kg/d, gavage |

| E | 7 | mid-dose ICA and ICI 182780 | ICA 150 mg/kg/d, gavage; ICI 182780 1 mg, subcutaneous injection daily |

| M | 7 | placebo (model control) | CMC 0.3 ml, gavage |

| N | 6 | placebo (normal control) | CMC 0.3 ml, gavage |

Serology test for IL-17, CORT

The mice were sacrificed 6 days after treatment and the sera were abstracted at the same time point. Serum concentrations of IL-17 was assayed by specific Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Kit (R&D systems, USA); Serum CORT was measured using specific radioimmunoassay kits (Sino-UK Institute of Biological Technology, Beijing, China) and GC-911γ--ray radioactive immunity analysis instrument (USTC Holdings Co., Ltd, Hefei, China).

Western blot analysis of GR, ERα and ERβ in cerebral white matter

Cerebral white matter in lateral ventricle was dissected. The corpus callosum and internal capsule tissues were collected and lysed in a RIPA buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, Jiangsu, China) containing protease inhibitors. Protein concentration was determined by BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Protein samples were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 and then incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-GR antibody (1:1000, Millipore), mouse monoclonal anti-ERα antibody (1:1000, Millipore), mouse monoclonal anti-ERβ antibody (1:1000, Millipore). Mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (1:6000, Millipore) was used as an internal control. Protein bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10000, Abcam). Scanned images were analyzed by Quantity One 1-D analysis software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD. The differences were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by the least-significant difference-multiple comparison test, Wilcoxon test, Wilcoxon test, Mann-Whitney u test or t test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

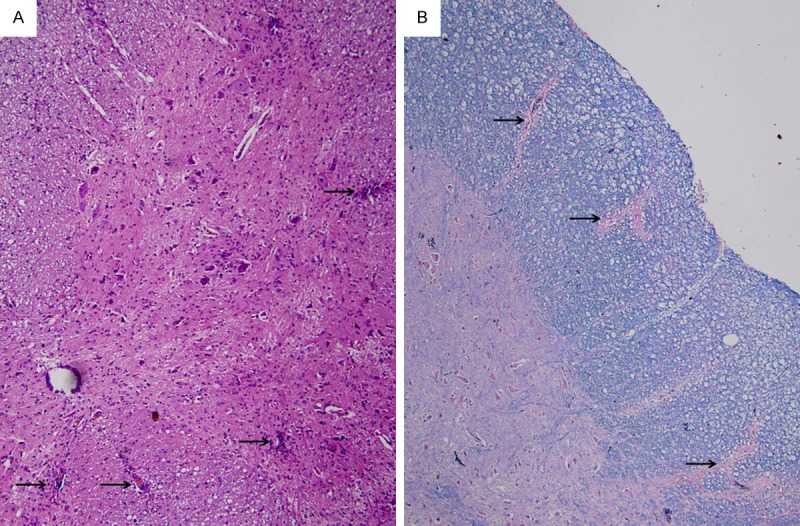

Clinical and pathological manifestations of EAE

The onset of EAE in mice was nine days after immunization. The first sign of illness was decreased appetite and weight loss. Afterward, the mice presented with distal tail weakness, which gradually developed into complete tail paralysis and various degrees of limb paralysis. Neurological signs developed at 11-12 days. Four EAE mice in the group C, D, E and M deteriorated quickly and died of severe illness. In the HE-stained EAE spinal cord, perivascular and parenchymal mononuclear cell infiltrates were observed in the gray and white matter, and a number of perivascular cuffs were seen. Solochrome cyanine staining showed various degrees of demyelination in EAE mice (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pathological staining. A. HE×100 (arrows indicate perivascular and parenchymal mononuclear cell infiltrates or cuffings). B. Solochrome cyanine×100 (arrows indicate demyelinations).

Comparison of clinical scores

The mean clinical scores were significantly reduced by estrogen and high-dose ICA (Table 2). Both were neuroprotective. There was no significant difference in clinical score changes between estrogen and high-dose ICA groups. While low-dose ICA treatment did not reduce clinical scores, mid-dose ICA was associated with a small but nonsignificant reduction. Administration of ICI 182780 with mid-dose ICA, however, led to much worse score similar to placebo group, suggesting that ICI completely abolished the neuroprotective effect of ICA.

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical scores in EAE (X ± SD)

| Group | n | Treatment | Before treatment | After treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 7 | estrogen | 2.57±0.79 | 0.67±0.52* |

| B | 7 | high-dose ICA | 2.42±0.67 | 1.25±0.29# |

| C | 6 | mid-dose ICA | 2.75±1.33 | 1.88±0.75 |

| D | 6 | low-dose ICA | 1.83±0.75 | 1.70±1.20 |

| E | 6 | mid-dose ICA and ICI 182780 | 1.92±0.80 | 2.25±0.87# |

| M | 6 | placebo | 2.08±0.86 | 2.25±1.33# |

Vs. before treatment;

P<0.01;

P<0.05 (Wilcoxon signed rank test).

There was no significant difference in clinical score changes between estrogen and high-dose ICA groups (Mann-Whitney u test).

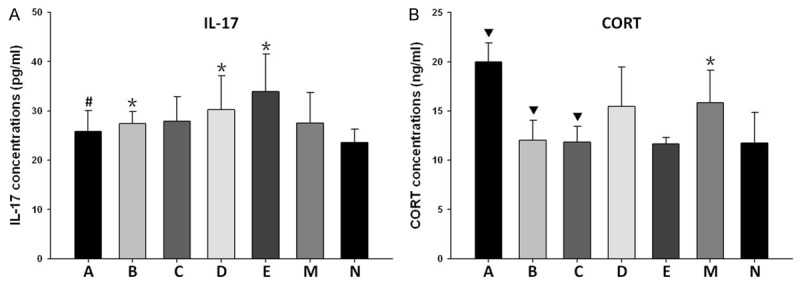

Comparison of IL-17, CORT

The concentrations of IL-17 in EAE mice were increased in comparison with that in the normal control group. Treatment with estrogen or different dose of ICA hardly decreased the levels of IL-17 in EAE mice as compared with placebo. In contrast, the level of IL-17 was increased in the group of mid-dose ICA combined with ICI 182780 compared to estrogen group (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Serum concentrations of IL-17 and CORT. A. IL-17 concentrations (pg/ml): A, 25.85±4.21; B, 27.44±2.40; C, 27.86±4.98; D, 30.28±6.87; E, 33.87±7.67; M, 27.53±6.16; N, 23.55±2.75. B. CORT concentrations (ng/ml): A, 19.99±1.91; B, 12.01±2.04; C, 11.84±1.61; D, 15.45±4.02; E, 11.63±0.66; M, 15.86±3.26; N, 11.73±3.12. *P<0.05, vs. normal control group; #P<0.05, vs. group E; ▼P<0.05, vs. model control group (one-way ANOVA followed by the least-significant difference-multiple comparison test).

Similar to IL-17, concentrations of CORT were increased in the model control group as compared with normal control group. The levels were significantly decreased after the treatment of high-dose or mid-dose ICA, but not low-dose ICA. Differing from ICA, administration of estrogen increased the level of CORT compared to the model control group. In contrast to mid-dose ICA group, treatment with mid-dose ICA and ICI 182780 did not reverse the reduction of CORT level (Figure 2B).

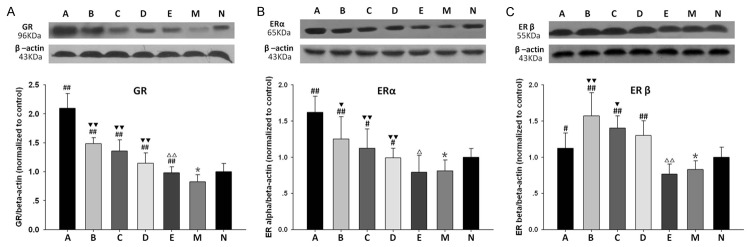

Expression of GR, ERα, ERβ

Densitometric analysis of Western blot revealed that the expression of GR decreased in model control group in contrast to normal control group. Treatment with ICA dose-dependently promoted the expressions of GR as compared with model control group. It was enhanced more remarkably by the administration of estrogen in comparison with that in different dose ICA groups. ICI 182780 pretreatment effectively eliminated the elevation of GR level induced by mid-dose ICA (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Densitometric analysis of GR (A), ERα (B), ERβ (C) expressions. *P<0.05, vs. normal control group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, vs. model control group; ▼P<0.05, ▼▼P<0.01 vs. group A; ΔP<0.05, ΔΔP<0.01 vs group C (one-way ANOVA followed by the least-significant difference-multiple comparison test).

Likewise, the expressions of ERα and ERβ in model control group were also lower than that in normal control group. Both were up-regulated by the treatment of estrogen and different dose of ICA in a dose-dependent manner. Interestingly, estrogen induced the elevation of ERα more markedly than ICA (Figure 3B), while high-dose and mid-dose ICA treatment promoted ERβ significantly compared to estrogen (Figure 3C). These effects were abrogated by ICI 182780.

Discussion

Estrogens have a wide range of immunomodulatory activities in preventing progression of MS or EAE, decreasing recurrence rate, and reducing active lesions [2]. ICA was reported to have estrogen-like neuroprotective effects [18], but little is known about its effects on MS or EAE. In this study, we demonstrated that high dose ICA significantly ameliorates neurological signs in EAE in similar mechanisms. Since ER antagonist ICI 182780 abolishes its protective effects, ER is implicated in the molecular mechanisms of neuroprotection as well as estrogen.

IL-17 is mainly produced by Th-17 cells which is involved in the development of many autoimmune diseases, including MS, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis [19]. IL-17 mRNA was increased in the blood and CSF of MS patients [20], and the increased production of IL-17 was detected in the brain during early EAE [21]. The development of EAE was markedly suppressed in IL-17 gene knock-out mice [22]. These observations suggest that IL-17 is crucial for the pathogenesis of MS and EAE. Currently, estrogens were reported to have potential anti-inflammatory activities and have suppressive effects on the induction of EAE. E2 not only affects the expression and secretion of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines including IL-4, IL-10 and TNF-α, but also regulates the immune responses especially in the differentiation towards regulatory responses [4]. ICA was also shown to have potential anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating activities. ICA decreases Th17 cells and suppresses the production of IL-17 in mice with collagen-induced arthritis [23]. ICA also triggers a significant reduction in IL-6, IL-17 and TGF-β levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids cells [24]. We demonstrated increased serum IL-17 concentrations in EAE mice that were not regulated by estrogen or different dose of ICA. Nevertheless, IL-17 level was increased by ER antagonist, suggesting potential role of ER in the modulation of IL-17 production.

Decreased hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function may play an important role in the increased susceptibility and severity of MS [25,26]. Hyper- and hypoactivity of the HPA axis have been described to be associated with more severe disease courses [27]. In animals, CORT is the primary GC whose level responses to the activity of HPA axis. There is clear evidence that disruption of HPA axis results in increased CORT level, which may delay the progression of inflammatory state in EAE. In the present study, the serum CORT level was elevated in EAE mice, which could be obviously decreased by the treatment of high-dose or mid-dose ICA. It indicated that ICA has effect on the modulation of HPA axis via inhibiting CORT. However, ICA combined with ER antagonist hardly changed the level of CORT, suggesting that the HPA axis may not be modulated by ER pathway. It is unclear why estrogen increases CORT level. Complicated as the mechanisms of HPA axis modulation are, the underlying hypotheses responsible for ICA mediating CORT remain elusive.

ICA was shown to significantly increase GR mRNA and protein expression in the lungs of mice exposed to smoke, stress and allergen [28,29]. ICA also attenuates social defeat-induced down-regulation of GR in the liver and hippocampus of mice model for depression [30,31]. Similarly, we demonstrate a dose-dependent enhanced GR expression in the cerebral white matter of EAE mice after ICA treatment. Furthermore, we observed that the up-regulation of GR by ICA could be inhibited by ER antagonist, implicating an role of ER in the regulation of GR and anti-inflammatory activities of ICA.

ER is widely expressed in different tissue types. ERα is mainly in reproductive tissues (uterus, ovary), breast, kidney, bone, white adipose tissue and liver, while expression of ERβ is found in the ovary, central nervous system, cardiovascular system, lung, male reproductive organs, prostate, colon, kidney and the immune system [32,33]. Activated ER by estrogen could be translocate into the nucleus and bind to DNA to regulate the activity of different genes, resulting in activation or inhibition of the basal transcription protein machinery. These genomic estrogen effects are involved in the modulation of immune and inflammatory processes in many diseases.

Admittedly, estrogen is neuroprotective in EAE [34,35]. Treatment with either ERα ligand or ERβ ligand ameliorated EAE [36-38]. However, the efficacy of estradiol could be eliminated in ERα knock-out EAE mice, but not in ERβ knock-out mice [36]. ERα expression on astrocytes, but not ERβ expression on astrocytes or neurons, is necessary for estrogen-mediated neuroprotection in EAE [39]. These findings indicate that the biological effects of estrogens in EAE are mediated mainly by ERα. In the current study, we demonstrate that estrogen and ICA significantly increase the expressions of both ERα and ERβ in cerebral white matter. Notably, estrogen increases the expression of ERα more than ICA. ICA enhances ERβ more significantly than estrogen. These results reveal an important difference in ER isoform regulation between ICA and estrogen. We reveal the estrogen-like activity of ICA in EAE via interactions with ERβ for the first time. It is unclear if ERβ pathway is associated with less side effects of phytoestrogen. Instead of targeting to the extensive tissue distribution of ERα, ICA interacts with relatively limited distribution of ERβ will probably induce fewer adverse complications than estrogen.

In conclusion, ICA exerts estrogen-like activity in ameliorating EAE via mediating ERβ, modulating HPA function, and up-regulating the expression of GR in cerebral white matter. As a major constituent of flavonoids from the Chinese medicinal herb Epimedium brevicornum, ICA has similar neuroregulatory and neuroprotective activities but less side effect than estrogen, ICA may be promising therapeutic option for MS.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81173418).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Langer-Gould A, Garren H, Slansky A, Ruiz PJ, Steinman L. Late pregnancy suppresses relapses in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: evidence for a suppressive pregnancy-related serum factor. J Immunol. 2002;169:1084–1091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niino M, Hirotani M, Fukazawa T, Kikuchi S, Sasaki H. Estrogens as potential therapeutic agents in multiple sclerosis. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:87–94. doi: 10.2174/187152409788452054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu HY, Buenafe AC, Matejuk A, Ito A, Zamora A, Dwyer J, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Estrogen inhibition of EAE involves effects on dendritic cell function. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:238–248. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Javadian A, Salehi E, Bidad K, Sahraian MA, Izad M. Effect of estrogen on Th1, Th2 and Th17 cytokines production by proteolipid protein and PHA activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from multiple sclerosis patients. Arch Med Res. 2014;45:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adlercreutz H. Phyto-oestrogens and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:364–373. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00777-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao E, Mu Q. Phytoestrogen biological actions on Mammalian reproductive system and cancer growth. Sci Pharm. 2011;79:1–20. doi: 10.3797/scipharm.1007-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacks FM. Dietary phytoestrogens to prevent cardiovascular disease: early promise unfulfilled. Circulation. 2005;111:385–387. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155232.57701.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soni M, Rahardjo TB, Soekardi R, Sulistyowati Y, Lestariningsih , Yesufu-Udechuku A, Irsan A, Hogervorst E. Phytoestrogens and cognitive function: a review. Maturitas. 2014;77:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Anazi AF, Qureshi VF, Javaid K, Qureshi S. Preventive effects of phytoestrogens against postmenopausal osteoporosis as compared to the available therapeutic choices: An overview. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2011;2:154–163. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.92322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang HK, Choi YH, Kwon H, Lee SB, Kim DH, Sung CK, Park YI, Dong MS. Estrogenic/antiestrogenic activities of a Epimedium koreanum extract and its major components: in vitro and in vivo studies. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:2751–2759. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Shen C, Chu J, Zhang R, Li Y, Li L. Icariin decreases the expression of APP and BACE-1 and reduces the beta-amyloid burden in an APP transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Biol Sci. 2014;10:181–191. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu B, Xu C, Wu X, Liu F, Du Y, Sun J, Tao J, Dong J. Icariin exerts an antidepressant effect in an unpredictable chronic mild stress model of depression in rats and is associated with the regulation of hippocampal neuroinflammation. Neuroscience. 2015;294:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J, Du J, Xu C, Le J, Liu B, Xu Y, Dong J. In vivo and in vitro anti-inflammatory effects of a novel derivative of icariin. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2011;33:49–54. doi: 10.3109/08923971003725144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi MY, Kai C, Liu HR, Su YH, Yu SQ. Protective effect of Icariin on the early stage of experimental diabetic nephropathy induced by streptozotocin via modulating transforming growth factor beta1 and type IV collagen expression in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;138:731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh TP, Sheu SY, Sun JS, Chen MH, Liu MH. Icariin isolated from Epimedium pubescens regulates osteoblasts anabolism through BMP-2, SMAD4, and Cbfa1 expression. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:414–423. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bittner S, Afzali AM, Wiendl H, Meuth SG. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG35-55) induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in C57BL/6 mice. J Vis Exp. 2014 doi: 10.3791/51275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becher B, Durell BG, Noelle RJ. Experimental autoimmune encephalitis and inflammation in the absence of interleukin-12. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:493–497. doi: 10.1172/JCI15751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen R, Deng W, Li C, Zeng G. A natural flavonoid glucoside icariin inhibits Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;24:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin W, Dong C. IL-17 cytokines in immunity and inflammation. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2013;2:e60. doi: 10.1038/emi.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matusevicius D, Kivisakk P, He B, Kostulas N, Ozenci V, Fredrikson S, Link H. Interleukin-17 mRNA expression in blood and CSF mononuclear cells is augmented in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 1999;5:101–104. doi: 10.1177/135245859900500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wojkowska DW, Szpakowski P, Ksiazek-Winiarek D, Leszczynski M, Glabinski A. Interactions between neutrophils, Th17 cells, and chemokines during the initiation of experimental model of multiple sclerosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:590409. doi: 10.1155/2014/590409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komiyama Y, Nakae S, Matsuki T, Nambu A, Ishigame H, Kakuta S, Sudo K, Iwakura Y. IL-17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:566–573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chi L, Gao W, Shu X, Lu X. A natural flavonoid glucoside, icariin, regulates Th17 and alleviates rheumatoid arthritis in a murine model. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:392062. doi: 10.1155/2014/392062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei Y, Liu B, Sun J, Lv Y, Luo Q, Liu F, Dong J. Regulation of Th17/Treg function contributes to the attenuation of chronic airway inflammation by icariin in ovalbumin-induced murine asthma model. Immunobiology. 2015;220:789–797. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huitinga I, Erkut ZA, van Beurden D, Swaab DF. The hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in multiple sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;992:118–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melief J, de Wit SJ, van Eden CG, Teunissen C, Hamann J, Uitdehaag BM, Swaab D, Huitinga I. HPA axis activity in multiple sclerosis correlates with disease severity, lesion type and gene expression in normal-appearing white matter. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:237–249. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heesen C, Gold SM, Huitinga I, Reul JM. Stress and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis - a review. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:604–618. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li L, Sun J, Xu C, Zhang H, Wu J, Liu B, Dong J. Icariin ameliorates cigarette smoke induced inflammatory responses via suppression of NF-kappaB and modulation of GR in vivo and in vitro. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B, Duan X, Xu C, Wu J, Liu B, Du Y, Luo Q, Jin H, Gong W, Dong J. Icariin attenuates glucocorticoid insensitivity mediated by repeated psychosocial stress on an ovalbumin-induced murine model of asthma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;19:381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu X, Wu J, Xia S, Li B, Dong J. Icaritin opposes the development of social aversion after defeat stress via increases of GR mRNA and BDNF mRNA in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2013;256:602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu J, Du J, Xu C, Le J, Xu Y, Liu B, Dong J. Icariin attenuates social defeat-induced downregulation of glucocorticoid receptor in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;98:273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Couse JF, Lindzey J, Grandien K, Gustafsson JA, Korach KS. Tissue distribution and quantitative analysis of estrogen receptor-alpha (ERalpha) and estrogen receptor-beta (ERbeta) messenger ribonucleic acid in the wild-type and ERalpha-knockout mouse. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4613–4621. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.11.5496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jia M, Dahlman-Wright K, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta in health and disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;29:557–568. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gold SM, Voskuhl RR. Estrogen treatment in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;286:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spence RD, Voskuhl RR. Neuroprotective effects of estrogens and androgens in CNS inflammation and neurodegeneration. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morales LB, Loo KK, Liu HB, Peterson C, Tiwari-Woodruff S, Voskuhl RR. Treatment with an estrogen receptor alpha ligand is neuroprotective in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6823–6833. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0453-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tiwari-Woodruff S, Morales LB, Lee R, Voskuhl RR. Differential neuroprotective and antiinflammatory effects of estrogen receptor (ER)alpha and ERbeta ligand treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14813–14818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703783104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crawford DK, Mangiardi M, Song B, Patel R, Du S, Sofroniew MV, Voskuhl RR, Tiwari-Woodruff SK. Oestrogen receptor beta ligand: a novel treatment to enhance endogenous functional remyelination. Brain. 2010;133:2999–3016. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spence RD, Wisdom AJ, Cao Y, Hill HM, Mongerson CR, Stapornkul B, Itoh N, Sofroniew MV, Voskuhl RR. Estrogen mediates neuroprotection and anti-inflammatory effects during EAE through ERalpha signaling on astrocytes but not through ERbeta signaling on astrocytes or neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:10924–10933. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0886-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]